Marc Weidenbaum's Blog, page 349

February 3, 2016

La Voix Humaine

Denise Duval sang passionately about broken telephone connections, about the way our technology can mimic, taint, and amplify human connections. She died a week ago, on January 25, the New York Times reported today.

A French soprano born in 1921, Duval is best known for her work with the composer Francis Poulenc. Foremost among the pair’s collaborations is the opera La Voix Humaine, based on the play by Jean Cocteau. La Voix Humaine is high on the list of essential viewing and listening if you’re interested in art informed by technologically mediated human interaction.

The opera tells the story of the end of a love affair. Expertly constructed, it unfolds as one half of a phone conversation. The other half takes place on the far end of the phone line, unheard by the audience. The woman is Elle, and Duval was the first to perform the role. There’s a filmed version of Duval’s performance, directed by Dominique Delouche, which uses another technology, television, to emphasize the creative constraints inherent in Cocteau’s vision: a woman, alone in a room, trying to navigate a failed love — and her own faltering psyche — using failing technology.

I spent a chunk of last year working on — and failing at — an extended essay about the intersection of art and technology that just never ended up going where I’d hoped it would. Only toward the end of the writing process, before I put it away half-finished, did I finally switch from wondering about the relationship between the artist and the technology and, instead, began to focus on the audience’s experience of technology. At that point I’d blown too much time and just couldn’t dedicate myself to it anymore, though I hope to get back to it at some point.

This morning, having read the news of Duval’s death over coffee, I was reminded of the centrality of that telephone in La Voix Humaine, not just to Elle, but to the audience of both the play and the opera. The play was first performed in 1930, the opera in 1958. By 1970, when Delouche’s filmed version was broadcast on television in France, the phone was long since not just an everyday but essential part of life. To witness Elle’s story in 1930 must have been a very different thing than in 1970, from the perspective of an audience’s experience of the phone as a lifeline. There is something very J.G. Ballard about La Voix Humaine, as if it’s taking place amid the narrative of his novel High Rise, like Elle lives in an apartment whose door the book’s narrator never happens to knock on.

Eventually La Voix Humaine did leave the boudoir. For example, a staging by the Cincinnati Opera’s Nicholas Muni in 2003 re-situated Elle (soprano Catherine Malfitano, above) as the survivor of a car accident. We witness Elle wandering around the wreck while she tries to communicate with her former lover. The wreck isn’t merely a contrivance to switch to a cellphone. It’s part of the original story that Elle reveals her attempted suicide. In the Muni depiction, the scene of the accident serves as both setting and evidence. Of course, switching to cellphone in 2003 also made sense because the phone needed to cut off once in awhile, something far more common then — and today — on a cellphone than on a landline.

The lingering lesson of La Voix Humaine may be that if you’re making technological art, ask yourself if you are reflecting on the means by which that technology is infused in the lives of its audience.

The Delouche version with Duval is on YouTube in four parts. The image up top was colorized (and found at tutti-magazine.fr). The original is in black and white.

Also on YouTube is an Ingrid Bergman (above) version of the play, from 1967.

And to bring things back around to electronic music, there’s an audio-only version of the play done for the BBC by Scanner, aka Robin Rimbaud, that was first broadcast back in 1998. It stars Harriet Walter, best known these days as Lady Shackleton on Downton Abbey and as the doctor who briefly but memorably tends to Chewbacca in Star Wars: The Force Awakens. The Human Voice is an important transitional work for Rimbaud, as it employs techniques he developed when making music to accompany cellphone conversations captured on scanners (hence his moniker), but applies them to prerecorded dialogue — or, in this case, monologue.

This first appeared in the February 2, 2016, edition of the free Disquiet “This Week in Sound” email newsletter: tinyletter.com/disquiet.

Vowels Accumulate Over Days and Months

Yesterday, on a brand new SoundCloud account, the artist Steph Horak posted a track of layered vocals, just tones, just soft vowels, that when played against each other yield a familiar, lovely, gently abrasive beading that sounds less like a choir of one and more like a glass harmonica played by an expert soloist. Her explanation is that it’s part of an art project that accrues and amasses individual tones over time on a regular basis.

Here is Horak’s description:

I am attempting to sing a note a day for a year because I want to know if my body holds a certain tension, or harmony, a resonant bias. Therefore, I record each day’s note in isolation, without hearing any of the previous days, and then I make a mix of the month. This is a somewhat indulgent side-project. This is not about singing in tune. This is about data. Trigger warning: People with absolute pitch may find this jarring to listen to.

The track is labeled “366 JANUARY 2016,” though it’s unclear how much time is accounted for, how many vowels over how many days.

Track originally posted at soundcloud.com/threehundredandsixtysix. More from Horak at her other SoundCloud account, soundcloud.com/sheisrevolting, and at stephhorak.wordpress.com and noisevagina.tumblr.com, the latter of which includes this intriguing sonified lipstick case:

Horak works as part of the computing department at Goldsmiths, University of London, where she earned an MA in 2013. (Track found via a repost by soundcloud.com/leafcutterjohn.)

February 2, 2016

When a Drone Seems More Traditionally Musical Than Other Drones

All drones are not created equal. Not that one is better, by some measure, than another, but that between intent and tonality, density and momentum, texture and form, they are as different from each other as the ear might allow. Many drones have an industrial quality, like the finely crafted noise of either a well-oiled or nostalgically archaic machine. Some are expressly synthesized, devoid of any semblance of earthy quality. And some are, by some manner, musical — in the traditional sense of the word. They may have no apparent melody — they are still, in the end, drones — or rhythm, but there’s something to the harmonic staging and the sound quality itself that seems less like an industrial machine and more like, say, a pop song put in suspended animation. That’s the sort of drone that Rob Kriston created with “Toneless Dying Heart.” It’s beautiful and ever-shifting, a florid and chaotic timbre spectacle.

Track originally posted at soundcloud.com/robsville. More from Kriston at robkriston.com

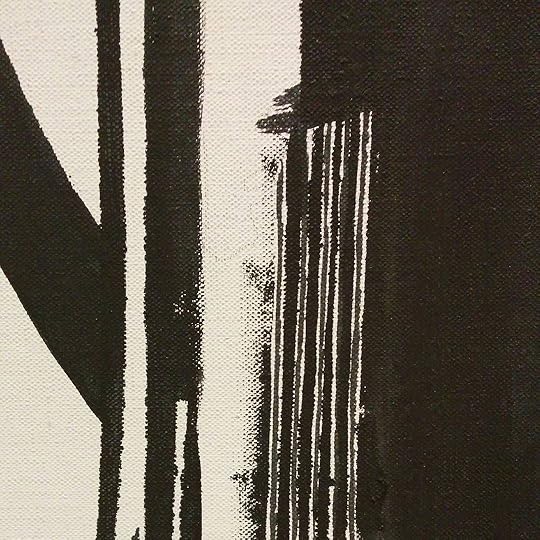

What Sound Looks Like

This is a detail of a phone, as painted by Andy Warhol. Like the work of Roy Lichtenstein, Warhol’s paintings often don’t translate well when reproduced. The situation is ironic since reproduction was the subject of so much of both men’s work. Printed on the page of a book or on a poster, a Lichtenstein study of moire patterns and the four-color printing process becomes far more perfect than it is in person, so perfect as to essentially eradicate the very inaccuracies in which it initially reveled. This image is a closeup of the side of the mouthpiece to a telephone. It’s from Warhol’s acrylic and pencil Telephone, which dates from 1961. I shot this, and some other angles of the original, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles while on a brief vacation there this past December. From across the room you see a classic old phone caught head on, the earpiece atop a stately black column, the mouthpiece connected by a thick licorice cord. As you approach the painting, the black and white image reveals two different meanings of white. There’s the white of the blank background, against which the phone is situated, and then there’s the white on the phone itself. This latter white represents reflection. This second white looks white, but it’s black — it’s the black where the light hits the phone. Closer still and the details become all the more apparent: tentative tracings, light washes that reveal the pattern in the canvas, and cautious swirls meant to approximate the genuinely mechanical.

Additional images:

An ongoing series cross-posted from instagram.com/dsqt.

February 1, 2016

“Moths Drink the Tears of Sleeping Birds”

When you think string quartet, certainly you think about creepy flying life forms in Africa that feed of the tears of other flying life forms. That is the scenario that informs Anna Höstman’s tensile and invigorating string quartet “Moths Drink the Tears of Sleeping Birds.” Premiered on November 14 of last year, the work is as slow and steady as you might expect of something that preys on things far larger than itself. The work moves from slow sawing to angular, intense slashing. At 15 minutes, it produces an impression of the scenario that is thick with drama. Certainly there is an intensity in the brief moments of fierce action, but the real beauty comes from the patience, both in the composition and the performance, to layer textured, paper-thin lines atop one another for extended periods of anxious near-silence.

Look closely at this image (from newscientist.com) and you’ll see the moth’s dagger-like nose stuck into a bird’s eyelid:

Here’s an extreme closeup, from the National Institutes of Health (nih.gov), that provides eerie detail of the moth’s sharp nose:

A brief program note by Deborah MacKenzie provides further background:

Scientists have recently revealed that a species of moth in the Kirindy forest of Madagascar drinks tears from the eyes of birds. Birds can usually fly away from these predators, but not while sleeping. The Madagascan moths were observed on the necks of sleeping magpie robins and Newtonia birds, with the tip of their proboscises inserted under the bird’s eyelid, drinking avidly. Sleeping birds have two eyelids, both closed. So instead of the soft, straw-like mouthparts found on tear-drinking moths elsewhere, the Madagascan moth has a proboscis “shaped like an ancient harpoon,” with hooks and barbs. It is inserted under the eyelid where the barbs are used to anchor it in place. The team does not yet know whether the insect spits out an anaesthetic to dull the irritation. They also want to investigate whether, like their counterparts elsewhere, the Madagascan tear-drinkers are all males who get most of their nutrition from the tears.

The piece by Höstman brings to mind another recent work of chamber music that has its basis in the dark corners of the natural sciences, “Euphorbia,” composed by Ylva Lund Bergner, heard in a performance by the Curious Chamber Players. Her piece’s name, and mood, come from a deadly plant in Denmark.

Track originally posted at soundcloud.com/annacomposer. More on Höstman at annahostman.net. More on Quatour Bozzini at quatuorbozzini.ca. More on the moth at newscientist.com.

January 31, 2016

When a Musical Composition Achieves the Undirected Manner of a Field Recording

So often the audio that emanates from Kate Carr’s SoundCloud account is field recordings, the experience can be jarring when something more traditionally recognizable as “music” appears in the feed’s sequence. “Things That Stubbornly and Resiliently Subsist Without Leave,” uploaded about a month ago, is no song in the traditional sense. It opens with solo electric guitar, plucked in a quiet, patient manner, before fading suddenly into a chillingly metallic echo chamber. Then comes a more sinuous synthesized sequence that bobs slowly this way and that — it’s as if a melody had been laid on the ocean’s surface and left to ebb and flow accordingly. And then comes silence, not digital silence but the silence of a room in which not very much seems to be happening, the sort of silence that can be consuming: drawing the listeners in and then imagined building walls around them. Lending the otherwise disparate sequence a sense of compositional structure, the piece shifts back for brief codas of the guitar and the chill. Leave it to Carr to produce a musical track that retains all the linear yet undirected semi-randomness of a field recording. She credits the title to Marie Thompson and Ian Biddle’s Sound, Music, Affect: Theorising the Sonic.

Track originally posted at soundcloud.com/katecarr. More from Carr at katecarr.bandcamp.com, gleamingsilverribbon.com, and twitter.com/flamingpines.

January 30, 2016

A Nervous Itch in Darren Harper’s Blissed Out “The Yearning Loop”

Darren Harper has posted a track from an upcoming EP. The EP is titled Winter Loops, and it’s due out soon. The track is “The Yearning Loop,” which appeared today on his SoundCloud account. Despite the singular “loop” in the title, it’s based on various subloops — a loping, low-slung bass line; a bit of happily meandering guitar that bounces in the stereo field; a rich ambient foundation; some hauntingly ethereal vocals. And from the very start, there is the subtle star of the performance, this little scratchy noise, like the end of tape that’s run out, or a piece of fabric fluttering in the lattice of a slow-moving fan. It’s a nervous little itch in the otherwise blissed-out drone. It’s there throughout, even as “The Yearning Loop” fades, a fine example of how the most mechanical element can seem the most natural, what might initially sound rote appearing, instead, like a model of persistence.

Track originally posted at soundcloud.com/darrenharper. More from Harper, who’s based in Colorado, at darrenjh.blogspot.com and twitter.com/darrenjharper.

This Week in Sound: Microtonal Errata + Party Lines

A lightly annotated clipping service:

Horse Bests Other Horse: News came this week that old music outsold new music for the first time in recorded history — or, in this case, recorded recorded history. Adam Puglsey lays out the situation at chartattack.com. Of course, as he also writes: “Keep in mind that these stats don’t include album streams, but regardless, it’s a significant turning point.” Which is to say, this may be like saying one breed of horse outsold another breed of horse for the first time after the introduction of the automobile.

The History of the Phone Is the Future of the Phone: Speaking of ahistoricism and technology, at medium.com, Peter Rojas talks about a new phone service called Unmute. It’s an app for conducting phone calls, with one added feature: “anyone can listen in on the calls. In fact, having a conversation in public is the whole point of Unmute, which is why we find it so compelling as a product.” This future-tech platform is vaguely reminiscent of what was, before the advent of widespread individual-household phone service, called a party line. Older baby boomers and their parents can recall apartment buildings and rural regions alike having shared lines. Pick up the phone at the wrong — or, depending on your predilections, right — moment and you get not only an earful of local gossip, but you can participate, as well. More on Unmute, which unlike party lines will provide an MP3 at the end of the call, at onunmute.com.

The Tantalizing Promise of the Applbum: Apps have been the new albums — the “applbum,” perhaps — for awhile now, and though the hybrid isn’t exactly a fulfilled promise, it continues to bear fruit. Adrift, the blissful and expertly glacial generative ambient experience by Loscil (aka Scott Morgan), was released for iOS late last year, and in a (sadly) rare instance of platform equity it popped up this week in an Android version. Well, not directly Android. It’s not in the Google Play Android app store, but in Amazon’s app bazaar. I asked Loscil/Morgan why via Twitter, and he explained that the Android max size was 100 megabytes (“i can’t afford the dev cost of adding expansion packs”), while Amazon has no app-size cap. The size is due to the app’s expansive sonic content that yields its generative (i.e., ever-changing) listening experience. … Meanwhile, Massive Attack has released a new album … that is, app, titled Fantom, that is billed as a sensory experience. Presumably “sensory” implies “interactive,” since music is itself sensory and “interactive” is simply a term that may have outlived its utility before that utility had actually been realized. The thefantom.co site explains: “The remixes reflect your movement and balance, the time of day or night, your location and your surroundings as captured by your device’s camera.” At the moment the link to the iTunes store isn’t yielding the app, but Tom Fenwick at motherboard.vice.com has some in-depth coverage, including the fact that one of the developers is Rob Thomas. The article doesn’t mention this, but Thomas is the former Chief Creative Office of Reality Jockey, where he helped develop the app RJDJ, which used a unique “scenes” scenario to alter in real time the sounds your phone or iPod picked up. RJDJ led, in turn, to several other apps, including ones associated with Christopher Nolan films, such as Inception. More from Thomas himself at soundcloud.com/dizzybanjo.

Nanonews about Microtones: In 1958, Alain Danielou published Tableau Comparatif des Intervalles Musicaux, which to an outsider (whether or not they speak French) might look like a codebook out of The X-Files or the Conet Project. What it is is an encyclopedia of microtones — in Gann’s description, “of all even marginally significant intervals within an octave.” A keen-eyed correspondent of Gann’s recently noticed an error: “On the right-hand bottom corner of page 48, the interval listed as 569/512 should actually be 567/512, as 3 to the 4th power times 7 is, of course, 567.” Here is the evidence:

As mistakes in tonal esoterica go, Gann notes, this one actually has some currency: “this is one of the intervals used in The Well-Tuned Piano” (one of La Monte Young’s great works). Gann, whose long-ago Village Voice music criticism was essential reading for me and many others back in the day, blogs at artsjournal.com/postclassic, where this notice first appeared. His Danielou article includes a link to a complete PDF of the Tableau book.

This first appeared in the January 26, 2016, edition of the free Disquiet “This Week in Sound” email newsletter: tinyletter.com/disquiet.

January 29, 2016

There’s a Thin Line Between Noise and Ambient

It can be informative to note that sometimes the difference between ambient music and noise music is simply a matter of volume. Played loud, a piece is a barrage; played quietly, it’s background ambience. But what happens when that background ambience is itself pitched down several notches. Titled “Inwards [005]” and tagged #silence, this piece by the Greek musician who goes by Simpsi begins so quietly you might think it’s entirely #silent. The music slowly makes itself somewhat apparent. It sounds like flowing, gently warping sine waves buffeted by some natural resource, like a passing breeze. And yet it’s in fact so quiet that its actual contours remain quite out of reach. It’s like the sound of a UFO landing just out of sight. Or maybe nothing is there at all.

Track originally posted at soundcloud.com/simpsimusic. Simpi is Panagiotis Simsiroglou of Athens, Greece.

January 28, 2016

A Mixtape Singularity

I’m ripping old cassette mixtapes and burning them to CD for a friend’s birthday party, marking a significant milestone — the party, not the ripping. It used to take a long time to rip a CD, almost as long as it did to listen to one. Then it took very little time at all. At some point the digital process sped up so much that the CD itself essentially disintegrated, or at least its utility did. That is, you no longer needed the CD at all. Audio had, in a manner, reached a singularity. Digital had accelerated to the point where you bypassed the physical medium entirely, and you listened directly to the digital audio file on a device that both stored and played back the file. The intermediary CD, that mirror-faced descendant of the vinyl LP and the tape cassette, was no longer a requisite.

Where streaming sits along or alongside this continuum remains a little unclear. Streaming is more like radio than it is like a recording medium. Radio can be said to have experienced its own parallel acceleration toward a singularity: optimization through automation of commercial broadcasts. Commercial radio went, over time, from a freeform medium to one managed by human beancounters, to one managed by algorithmic beancounters. At some point the algorithm decided for us — not unlike humanity’s helicopter parent at the center of D.F. Jones’s anxious artificial-intelligence novel Colossus, published in 1966, same year as the first Association for Computing Machinery Turning Prize — that the optimal ’cast scenario wasn’t broad-cast at all. Instead, the algorithm proclaimed beneficently, we should all stream what we want to stream.

In many instances, thousands upon thousands of people might be listening to the exact same song at roughly the same time, but off by a matter of seconds or minutes. Somewhere right now thousands upon thousands of people are listening to the latest momentarily popular verse-chorus-verse assemblage about failed or expectant romance. If we were able to listen to them all at once it would be a mutant version of the original: repeated, layered, looping back on itself, reaching crescendos of volume during peak listening, and fading out when the majority of the population in the target audience — Central Time Zone in North America, perhaps — happens to be asleep.

That communal sound, if we had access to it — if, say, the Spotify API could let us sync and produce such a pop-music ambient surveillance apparatus — might produce an apt sonic portrait of what it means to listen in culture, to listen to culture, at this moment. Imagine observing Spotify activity the way a service like Listen to Wikipedia (listen.hatnote.com), by Mahmoud Hashemi and Stephen LaPorte, allows us to observer activity on the global communal encyclopedia: we wouldn’t be listening to Spotify so much as Listening to Listening to Spotify.

I have a dream where observing that streaming process becomes not just technically possible but genuinely popular, and pop music itself mutates to match the new norm. Songs as we known them would slowly disappear, replaced by rich, long miasmas: a slow-motion, longitudinal EDM of ambient pop. Paul Lamere is the Director of Developer Platform at Echonest, a division of Spotify. I asked him this past week if my dream API scenario could be implemented, and he said the current API doesn’t necessarily support it, but he pointed me to a visualization tool called Serendipity coded by Kyle McDonald during an arts residency there. McDonald’s Serendipity depicts pairs of people listening, per chance, to the same track within seconds of each other across the globe.

As for the ripping and burning of cassette tapes to CDs, it’s proceeding at its own, antediluvian pace. It’s very fast to burn a CD, but the tape needs to be recorded at its original speed. I have no fancy, double-speed cassette player, just this old stereo-system component. There are no functional silences on the tape, at least not by contemporary standards. In regard to these mixtapes, this isn’t simply because of the static of the tape’s own surface noise. It’s because the tape was itself second generation: most of these tracks were copied from LPs, so the CD versions are replicating not just the tape noise, but the vinyl noise, as well as whatever file-format compression is involved on the digital side of things. The residual file-format artifact is inaudible to me, and probably to most people. Perhaps down the road we’ll be able “hear” that something was an MP3 or a Wav or a FLAC file the way, today, we can “hear” that something was vinyl or tape. The idea that a skill like that would become commonplace seems futuristic, but then again the idea of burning one’s own digital media once seemed futuristic — and now burning one’s own digital media doesn’t just seem antiquated; it is antiquated.

The original reason to make these tapes was just to have some dusty musical memories playing at the party, but it’s clear now that the music is only part of the memory process. The tape hiss and the vinyl crackle will provide their own ambience, as will the physical act of putting one of these CDs into a CD player. (A thumb drive is being filled up, too, just in case. In the world of Spotify playlists — and, yes, Apple Music and Google Play Music, among others — tiny portable hard drives are simply another, more recent antiquity.) The physical act of putting a CD into a player will initiate a surface hiss that will summon the physical act of putting a tape in a tape player, and in that tape noise there will appear the sound of a needle touching vinyl, triggering yet another memory of physical activity. Audio has passed its singularity, and in our post-physical listening mode we now hear echoes of our earlier, embodied listening. Nostalgia may be as much a fool’s game as is futurism, but heck, that’s what birthdays are for.

Right now, though, I’m just watching in a software program called Audacity to keep an eye on the audio levels of the source tape. When they flatline, I’ll know the tape is through.

This first appeared in the January 26, 2016, edition of the free Disquiet “This Week in Sound” email newsletter: tinyletter.com/disquiet.