Marc Weidenbaum's Blog, page 327

August 22, 2016

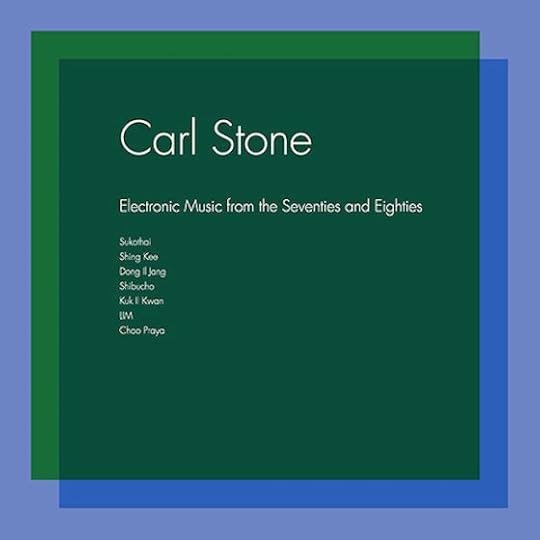

Liner Notes on Early Carl Stone

Carl Stone invited me to write liner notes to a forthcoming release of some of his early music, Electronic Music from the Seventies and Eighties. That is to say, early in his career; it’s not archaic woodwinds and pre-polyphony singing.The album is due out September 30 from the label Unseen Worlds (more at unseenworlds.com). The release will also include liner notes from Stone himself, and from Richard Gehr and Jonathan Gold.

The pieces I wrote about are described as follows: “The earliest works of this collection, ‘LIM’ and ‘Chao Praya,’ realized on the Buchla 200, date to the early 1970s while Stone was a student of James Tenney and Morton Subotnick at CalArts.”

The album is due out September 30 as a three-LP set. Here are my liner notes:

The composer Carl Stone is often associated with multi-channel work that immerses the listener in a spatial sonic zone, and with aggressive sample manipulation that explores its source audio from the inside. The two early Stone pieces, LIM and Chao Praya, are neither. Conceptualized and recorded between 1972 and 1974, they are elegant, built from limited resources. They may play with the stereo spectrum, but their intended breadth is reserved.

They are student work, in the sense that they were recorded while Stone was an undergraduate at CalArts in Los Angeles. The early 1970s were an especially heady time at CalArts. The composers Ingram Marshall and Charlemagne Palestine were graduate students there while Stone, an L.A. native, was earning his bachelor’s degree, Barry Schrader was among the school’s instructors, and Buchla synthesizers were available if not abundant.

They are student work, in terms of when Stone committed them to tape, but they are fully realized

performances, in the sense that four-plus decades later they are compelling, consuming listening experiences.

Chao Praya has at its heart the tingling wavering associated with a prayer bowl, or perhaps a police helicopter. It undulates, and in turn its various procedural wave forms reveal their constituent parts. Shades take on greater emphasis as increased volume brings details into focus.

LIM, in contrast with Chao Praya, often plays at higher registers and with greater variance. Here there are space ships rather than helicopters overhead. Here tonal shifts launch slow-motion cascades of moiré patterns. At even a modest volume, the results have a physical effect, playing with the ear. They tease at the nexus where sounds venture beyond human recognition.

Morton Subotnick, one of Stone’s teachers at CalArts, speaks of how he was drawn to electronic music when he began to dream music that an orchestra was not capable of producing. Stone’s is such music. This isn’t to say this work is opposed to the classical tradition. Quite the contrary, with their relatively compact length — barely 20 minutes combined — and economical contents, these two pieces have the air of études, of compositions that set out to explore a terrain, to map out combinations and permutations, the repercussions of resonances, and to set them down for study.

It is all too easy with the rise of digital media to credit the blank slate of streaming audio and the frictionless playback of solid-state drives with the level of nuance we experience in today’s sound design and audio recordings. Certainly these newfound comfort levels with quietude have created opportunities for musicians to nurse and adopt ambient proclivities. But the re-release of Chao Praya and LIM evidence that there are composers, Carl Stone key among them, who were working these elds from the beginning, who recognized at the start that new instruments would yield new forms.

Listening to Yesterday: The Bourne Acoustemology

The fifth Bourne movie, Jason Bourne, felt like something of a letdown, especially its ending — not because it fizzled, but because it exploded. The film’s final major sequence, a cartoonish vehicular rampage in Las Vegas, was the exact sort of overstuffed, overlong, physics-denying thriller set piece to which the first Bourne movie served as an antidote.

That first Bourne film was intimate, surgical, refined. The closeness of camera, the tight confines of many of the fight scenes, the internal drama of the story — it was thrilling, something that thrillers often forget to aspire to. The small scope of the first film was largely a matter of visuals and plotting, but it played out as well in the everyday ambience and, at times, in John Powell’s alternately percolating and droning score.

Having never even read any of the novels on which the series was based, I decided after leaving the Jason Bourne matinee deflated to try the first book, which shares its title with the first Bourne movie: The Bourne Identity, by Robert Ludlum. It hasn’t been my primary read these past few weeks. I’ve just been taking it in small doses. Not surprisingly, sound is a key part of Bourne’s slow-waking realization about his circumstances. For the 1% of the English-reading population unfamiliar with the Bourne character, he’s a skilled assassin who emerges from a coma with most of his memory blank; the first book and the first movie track the initial stages of Bourne piecing together the puzzle of his identity.

Bourne is surprised by his own senses in the book’s early pages, like when he gains perspective on his own heightened awareness during a gun battle: “There were enough shells left, he knew that. He had no idea how or why he knew, but he knew. By sound he could visualize the weapons, extract the clips, count the shells.” The detail of that perception was inherent in the experience of the first film as well. It marks a strong contrast to the fifth film, in which the audience loses track of how many cars have been torn to shreds like toilet paper. Later in the first book, as he is tracking down former acquaintances by following leads that are, in fact, simply shards of memories, he experiences familiarity through all his senses: “He had seen the large room before, the beams and the candlelight printed somewhere in his mind, the sounds recorded also.”

There’s a term for the inherent sonic potential of a given scenario, of a given setting, and that word is “acoustemology.” The acoustemology of the first Bourne book is about proximity and detail, about human scale and threats just out of sight. The book and the film alike feed on that dictum. Hearing in a narrative such as this is far more intimate than seeing. Heightened sight gives Bourne a clear view across a crowded room. Hearing, in contrast, brings things close, aligns the reader’s ears with those of the protagonist. That’s the sort of intimacy that the first film portrayed — up close, personal — and that the fifth film lost sight of.

August 21, 2016

The Generative Patch as Fixed Recording

Like yesterday’s featured video, this video pushes the legibility of live filmed performance. Yesterday’s technically involved multiple live takes overlaid, each obscuring the others, and the ambient quality of it having less to do with any individual performance in the first place and more with the chance correlations that occurred as a result of the post-production act of accrual. Today’s video, by Flohr, is too murky and unidentifiable to ever be mistaken as a tutorial. And, of course, any modular synthesizer piece, such as this, that employs self-generating patches thus involves little if any human interaction. The hand comes down from above, the scale and surprise a bit like a Monty Python animation, a couple times, but by and large, this is really a live performance as fixed document — a patch playing out in realtime as something set in stone nonetheless, or in this case set in plastic and metal. The piece, “Spring Reverb Feedback Paths” by Flohr, is a shiny, rapidly cycling shimmer worth putting on repeat.

Flohr is Eric Flohr Reynolds of Atlanta, Georgia. More from him at soundcloud.com/flohr and ericflohrreynolds.bandcamp.com.

It’s the latest piece I’ve added to my ongoing YouTube playlist of fine “Ambient Performances.”

Listening to Yesterday: Listening to Yesteryear

old rock’n’roll hits

a sales pitch on TV

The ad ran during cultural downtime, late in the evening, after the reruns and the news. Time Life was selling one of its many various-artists collections: Classic Love Songs of Rock & Roll, 152 pop songs from the 1950s and 1960s collected on eight CDs. The hosts of the half-hour segment were singers from that period: Bobby Rydell (“Volare”) and Darlene Love (“He’s a Rebel”).

What was of note was how the CDs were being sold, how they were being framed. “You could source the Internet, scour retail stores, or even rummage through your attic and you wouldn’t find all of these songs, but they’re all here,” one sales line went, tempting a testy couch potato to file a class action suit after actually doing a cursory YouTube search. “Why waste your time and money trying to find all these hits yourself? Time Life has done it all for you. Call or order online now,” a similar train of thought went later in the broadcast. The titles of songs, from so long ago, hinted presciently at their present nostalgic future, from the Shirelles’ “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow” to Little Caesar and the Romans’ “Those Oldies but Goodies (Remind Me of You).”

The temporal tension in the ad was between what was once fresh and what was now old. “The birth of rock and roll brought us a new sound, new artists,” it went, “and most importantly a new kind of love song.” The message was that the new of today didn’t hold a candle to what was once new: “Easier than downloading, no searching for songs, no trying to remember your favorite artists — take the CDs with you in the car, play them around the house, upload them. Just open the box and enjoy nearly seven hours of the best music.” (The “trying to remember” line seemed either unsavory or spot on, given Time Life’s aging audience.) There was no mention that the CD has as little in common culturally with Motown as does a smartphone streaming service. Perhaps the CD — itself outdated technology, however recently — can also be warmly embraced as an object of nostalgia. Unexpected allegiances are formed in the dustbin of history. Old isn’t necessarily better than new. Old new is better than new new.

This music, we were not so subtly informed, was tied to the physicality of the media on which it first played: “You’ll get all the songs we fell in love to, danced to, heard on the radio, in jukeboxes, and on our own 45s.” This remained the case even if the option to “upload” counted as part of the sales pitch.

August 20, 2016

Delay in Multiple Directions

Echo, reverb, delay — common elements in ambient music, as they take sound and expand the space in which the sound resounds, the space the sound suggests, the impression the effects in turn give of a large hall, a deep cistern, a lengthy corridor. By expanding that space, they make space the prevalent concept of the music, the organizing principle. Music that makes you think about its spaciousness makes you stop thinking about it merely as a forward progression. To think spatially is to think in multiple directions at once, and to think of them as having relatively equal value. Even if the spacious music isn’t expressly static, like a drone, it is still distinct from music that moves firmly from beginning to end.

All of this came to mind while listening to an overlay video by Bassling, aka Jason Richardson of Australia. He posted a piece in which multiple test runs of a Junto project — the current one, which involves providing a mini-tutorial for a favorite skill — are played atop one another. The impression is of echo, of a single motif repeating off into the distance. But the effect, the reality, is quite different. Certainly for each note there are others than follow, but it isn’t consistent in which of the layers the note is first heard. Likewise, the notes fade in near unison, rather than in sequence. Thus the echo effect is complicated significantly — made both flatter and more chaotic. The layering itself was inspired by a previous Junto project, one proposed by Brian Crabtree (a developer of the Monome grid instrument), called “layered sameness.”

More from Richardson on the piece at bassling.blogspot.com. Video originally posted at YouTube..

It’s the latest piece I’ve added to my ongoing YouTube playlist of fine “Ambient Performances.”

Listening to Yesterday: Call Signals

background noise

The phone call was solid, an interview as part of a project well underway, me asking questions, my interlocutor filling in blanks: responding in detail, informedly nudging the narrative, providing verbal source code. The line quality was below average from the start, never breaking up, never dropping off entirely, but the audio remained tentative throughout, like the conversation had already taken place and was being played back after several runs through a fax machine, a generous spray from a water gun, and week left out in the sun to dry.

The audio quality changed in phases, first muffled, then squelchy, then fairly clear, then jittery, then muffled again. The transitions were curt, quick. One minute the voice on the other end of the line sounded like it was submerged, the next like it was behind concrete, the next like a window had opened, doubling the background ambience.

At one point early on, a particular background clicking sound kicked in. Tick tock. Tick tock. A paranoid person would guess they’re being tapped. This clicking seemed more prominent than a wiretap telltale. It was also familiar: a turn signal. The voice on the other side of the line was in a car, driving. The voice on the other end of the line had a hand on a wheel. The sound quality transitions were about distance, and physical structures, and cell tower triangulation.

I suppose I could have been perturbed. The call was important, but I found myself pleased that the person on the other end of the line actually used turn signals, something so few people seem to do. What could have read as flaky and distracted instead read as responsible and attentive. To be clear, we were deep in conversation the whole time, recording it for later transcription. What I’m recording here, in text, is simply a recollection of tertiary impressions, of how the sound of the call impacted my experience of the conversation.

Toward the end of the call I noticed that the tick tock had ceased, and that the sound quality had been consistent for a minute or so. The interlocutor was no longer in a car. The interlocutor was now traveling by foot. Soon enough, the call was over, exactly on schedule. I could, perhaps, have been annoyed by the fact that the interlocutor was on the move the whole time, but instead I found myself admiring a certain mastery — discussion always on point, recollections immediate, all statements clear. The transcription will bear this out.

August 19, 2016

More from Lanois’ Ambient Album

The Anti- label has posted another track from Daniel Lanois’ forthcoming Goodbye to Language album. It’s even more tripwire and slipstream than the previously shared “Heavy Sun.” The new piece, “Deconstruction,” is even more likely to turn on a moment’s notice, and to shift subtly from one transient listening zone to the next. It plays almost like a trailer of the album, composed as it is of myriad small segments, muffled blasts of warped pedal steel, gaseous cloud effects in full force. It features Rocco DeLuca on guitar, though his performance, like Lanois’, is so deeply consumed by processing that the presence of the instrument is artfully muddied, to the extreme. The album will be released on September 9.

There’s also a video that, like the music, emphasizes atmosphere. It’s packed with images of Lanois at work, but they’re all through fish-eye lenses, or are filmed close up, or appear in quick, fractured moments:

Track originally posted at soundcloud.com/antirecords. More on the album at anti.com.

Listening to Yesterday: Father Robot

television sound design

[Yeah, spoilers. Boilerplate, polite version: I promise I don’t “spoil” anything that would have bothered me had I known about it in advance. That said, I cannot think of anything I have read or watched in my life that would have been spoiled had I known the plot-advancing facts. And this is not, I promise, a brief Cliffs Notes–style detailed summary of the story. Perhaps the only real way to “spoil” something is to detail any serious flaws in logic, to the extent that you then can’t get them out of your head. I can’t promise that I don’t to that — but neither can anyone else.]

In the director’s commentary to the American remake of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, David Fincher, a master of pixel-specific art direction, talks about the chance intrusion of a halo into a frame. There’s a scene in his film that takes place at a computer repair place. MacJesus, it’s called, in lieu of an actual Genius Bar. In the scene, a fluorescent light in the shape of a circle hovers above the head of our hero, the antisocial hacker Lisbeth Salander.

In the commentary he notes that contrary to appearances, this wasn’t planned. The production team didn’t realize how symbolic that lighting was going to appear until after the shoot was done. It seems like a rare instance of unplanned scenery for Fincher, who famously uses CGI to correct real-life settings to match his design expectations.

The TV series Mr. Robot owes much to Fincher, and not just how the plotting of the first season shares certain parallels to Fight Club, which like The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo is in part about outsiders wreaking havoc on the establishment. The parallel isn’t just character and plotting. The direction of Mr. Robot has a strong, exacting design sensibility — individuals framed in lower corners, rooms like stage sets, adherence to symmetry, an overarching hyperreality — that echoes Fincher’s aesthetic perfectionism. In the hands of the show’s creator, Sam Esmail, Mr. Robot aspires to the smudgier, dustier, dirtiest aspects of Fincher’s vision, and also has time, thanks to corporate-tower machinations, for Fincher’s more clinical tendencies, too.

This week’s episode, “eps2.5_h4ndshake.sme,” the 7th of the 12-part season, featured a significant revelation about the show’s setting. This revelation occurred after a group therapy session that the show’s protagonist, Elliot, has been participating in all season. We already know that the character played by Christian Slater (in a role that I like to think of as a spiritual descendent of his pop-anarchist character in the 1990 movie Pump Up the Volume) is in fact a mental image of Elliot’s deceased father — that Slater’s character is, quite literally, all in Elliot’s head. A side note: Like Mr. Robot, Pump Up the Volume was filled with as much prerecorded music as it was with a proper score, and the score to Pump Up the Volume was by Cliff Martinez, whose ambient approach to underscoring is now a veritable norm in the entertainment industry, and it’s a style employed artfully in Mr. Robot by Mac Quayle.

The woman who leads the therapy session tells Elliot late in the episode that she’s seen Elliot “talking to him.” Elliot thinks the woman means his father, but of course she doesn’t mean “him”; she means “Him.” She’s referring to Jesus; the group therapy sessions occur in a large room with a cross on the wall. She then leaves Elliot so he can have some private time in the sanctuary, and the cross comes into focus, with a sad little old-fashioned speaker directly below it. This placement is unlikely a chance occurrence, like the halo was in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. The visual formulation — the cross and the speaker together, as if they are collectively one totemic object, an image of the source of voices that it can be said people hear in their heads — is almost too perfect, but almost too perfect is the nature of Mr. Robot.

August 18, 2016

Listening to Yesterday: The Idle Revolution

nearly silent hybrid turing corner

There was a car idling as I walked to the bus from my house yesterday morning. Its engine was a rough, asthmatic purr. There was another car idling when I got off the bus. There was one idling when I grabbed a pupusa lunch to take to a friend’s apartment, and another when I stood waiting at the corner for the bus. I had second thoughts about the bus, because two conversations were scheduled in the next hour on my way downtown, and it felt rude to talk on the phone on the bus. Instead I used an app on my phone to engage a ride-share service. Soon enough the ride-share car arrived; it idled as I approached and got in.

When I got out of the car, two conversations later, another car near-silently passed by: a hybrid. At the corner, when I began to walk across the street, an electric car executing a turn came to a halt. Its wheels made a sound against the asphalt, quite exactly the sound of a large piece of rubber being abused, but the breaks were indiscernible, and the engine entirely absent, especially against the noise of downtown midday.

A sizable majority of ride-share vehicles, seemingly regardless of app affiliation, run on internal combustion engines, and the sound of their idling is something of a sonic signature of ride-sharing. Certainly there are HEV ride-sharing drivers, but those seem — to this pedestrian and habitual bus-rider — to be a small percentage of the overall makeshift fleet. The hybrid and electric cars represent one significant shift in vehicular technology, and the idle — as a sonic symbol of ride-sharing — represents another, and these two shifts seem to have little in common, to even be at cross-purposes. I’d like to see statistics about car models in ride-sharing and how they correlate with general consumer car use. One transportation revolution is signaled in silence, while another lingers on the street, awaiting a passenger, engine gently rumbling.

This morning the news was awash with stories about a ride-sharing service preparing in the very near future, later this month, to offer a self-driving car service — a third potential technological shift — in a major American city. Meanwhile, the ride-share driver waits for a fare to arrive, and the car’s idling seems like more than simply a sonic signature of a category of service; the idling seems to signal a lack of awareness of this third major vehicular shift, a threat to the driver’s economic well-being, that may occur down the road.

Disquiet Junto Project 0242: Share Yer Knowledge

Each Thursday in the Disquiet Junto group, a new compositional challenge is set before the group’s members, who then have just over four days to upload a track in response to the assignment. Membership in the Junto is open: just join and participate. A SoundCloud account is helpful but not required. There’s no pressure to do every project. It’s weekly so that you know it’s there, every Thursday through Monday, when you have the time.

This project was posted in the morning, California time, on Thursday, August 18, 2016, with a deadline of 11:59pm wherever you are on Monday, August 22, 2016.

These are the instructions that went out to the group’s email list (at tinyletter.com/disquiet-junto):

Disquiet Junto Project 0242: Share Yer Knowledge

The Assignment: Make (and annotate) a track that provides an example of a trick/skill/tip you want to share about a piece of musical software or hardware.

Please pay particular attention to all the instructions below, in light of SoundCloud closing down its Groups functionality.

Big picture: One thing arising from the end of the Groups functionality is a broad goal, in which an account on SoundCloud is not necessary for Disquiet Junto project participation. We’ll continue to use SoundCloud, but it isn’t required to use SoundCloud. The aspiration is for the Junto to become “platform-agnostic,” which is why using a message forum, such as llllllll.co, as a central place for each project may work well.

And now, on to this week’s project.

Project Steps:

Step 1: Think of a specific trick or skill or tip you have honed in regard a particular piece of music software or hardware.

Step 2: Create a piece of music in which that trick or skill or tip is intrinsic.

Step 3: Annotate the track to detail the trick/skill/tip.

Five More Important Steps When Your Track Is Done:

Step 1: Per the instructions below, be sure to include the project tag “disquiet0242” in the name of your track. If you’re posting on SoundCloud in particular, this is essential to my locating the tracks and creating a playlist of them.

Step 2: Upload your track. It is helpful but not essential that you use SoundCloud to host your track.

Step 3: This is a new task, if you’ve done a Junto project previously. In the following discussion thread at llllllll.co post your track:

http://llllllll.co/t/share-yer-knowle...

Step 4: Annotate your track with a brief explanation of your approach and process.

Step 5: Then listen to and comment on tracks uploaded by your fellow Disquiet Junto participants.

This project was posted in the morning, California time, on Thursday, August 18, 2016, with a deadline of 11:59pm wherever you are on Monday, August 22, 2016.

Length: The length is up to you. Between 30 seconds and two minutes seems about right.

Title/Tag: When posting your track, please include “disquiet0242” in the title of the track, and where applicable (on SoundCloud, for example) as a tag.

Upload: When participating in this project, post one finished track with the project tag, and be sure to include a description of your process in planning, composing, and recording it. This description is an essential element of the communicative process inherent in the Disquiet Junto. Photos, video, and lists of equipment are always appreciated.

Download: It is preferable that your track is set as downloadable, and that it allows for attributed remixing (i.e., a Creative Commons license permitting non-commercial sharing with attribution).

Linking: When posting the track online, please be sure to include this information:

More on this 242nd weekly Disquiet Junto project — “Make (and annotate) a track that provides an example of a trick/skill/tip you want to share about a piece of musical software or hardware” — at:

More on the Disquiet Junto at:

Subscribe to project announcements here:

http://tinyletter.com/disquiet-junto/

Project discussion takes place on llllllll.co:

http://llllllll.co/t/share-yer-knowle...

There’s also on a Junto Slack. Send your email address to twitter.com/disquiet for Slack inclusion.

The image associated with this project is by Susanna Bolle, and is used thanks to a Creative Commons license: