Marc Weidenbaum's Blog, page 249

February 28, 2020

Mursyid’s Exploration

There are periods of time when, for one reason or another, my listening focuses on an individual musician. Twice last week and, now, today, where my listening has settled is on the work of Fahmi Mursyid. I receive a lot of correspondence about music from publicists and musicians, and I balance the inbound recordings with what I myself come across online. To my mind, the feeds on my Bandcamp, SoundCloud, and YouTube accounts are just as valid as — if not more so than — the queries in my inbox. This live performance video shows Mursyid layering tones and sequences on his portable synthesizer. There’s a light, exploratory quality, in part because the song has a childlike aspect to it, and in part because the music sounds like the score to footage of an unmanned research vessel headed out to the great unknowns of deep space. All of Mursyid’s YouTube videos are explorations of a sort, pursuing sounds on a variety of devices and software applications. Highly recommended to add to your YouTube feed.

This is the latest video I’ve added to my YouTube playlist of recommended live performances of ambient music. Video originally published at YouTube.

February 27, 2020

Disquiet Junto Project 0426: Cellular Chorale

Each Thursday in the Disquiet Junto group, a new compositional challenge is set before the group’s members, who then have just over four days to upload a track in response to the assignment. Membership in the Junto is open: just join and participate. (A SoundCloud account is helpful but not required.) There’s no pressure to do every project. It’s weekly so that you know it’s there, every Thursday through Monday, when you have the time.

Deadline: This project’s deadline is Monday, March 2, 2020, at 11:59pm (that is, just before midnight) wherever you are. It was posted on Thursday, February 27, 2020.

These are the instructions that went out to the group’s email list (at tinyletter.com/disquiet-junto):

Disquiet Junto Project 0426: Cellular Chorale

The Assignment: Make music with the source audio from (and inspired by) a Patricia Wolf project.

Step 1: This is a collaboration with Patricia Wolf, based on her Cellular Chorus. Check it out at:

Step 2: Download the 64 source tracks of the Cellular Chorus at:

https://www.dropbox.com/sh/v0w2kl69ys9bzvx/AAC4Ydqg7KeGCuICxO6gIipEa?dl=0

Step 3: Create a new piece of music using only the source audio. Use as many of the samples as you’d like, but don’t add other sounds, or process the samples to any extent more than slightly altering the individual material.

Background. Patricia Wolf has said of her original piece: “Cellular Chorus is a work of spatialized aleatoric music using smartphones to bring people physically closer to have an interactive and collective experience with light and sound. The piece is played by each user visiting Cellular Chorus on their smartphones. … The sounds I made are meant to harmonize. There is no right or wrong way to play them. The intention of this piece is to repurpose your smartphone for deep listening, creative experimentation, and to immerse groups of people in a sound and light environment with face to face interactions.”

Seven More Important Steps When Your Track Is Done:

Step 1: Include “disquiet0426” (no spaces or quotation marks) in the name of your track.

Step 2: If your audio-hosting platform allows for tags, be sure to also include the project tag “disquiet0426” (no spaces or quotation marks). If you’re posting on SoundCloud in particular, this is essential to subsequent location of tracks for the creation of a project playlist.

Step 3: Upload your track. It is helpful but not essential that you use SoundCloud to host your track.

Step 4: Post your track in the following discussion thread at llllllll.co:

https://llllllll.co/t/disquiet-junto-project-0426-cellular-chorale/

Step 5: Annotate your track with a brief explanation of your approach and process.

Step 6: If posting on social media, please consider using the hashtag #disquietjunto so fellow participants are more likely to locate your communication.

Step 7: Then listen to and comment on tracks uploaded by your fellow Disquiet Junto participants.

Additional Details:

Deadline: This project’s deadline is Monday, March 2, 2020, at 11:59pm (that is, just before midnight) wherever you are. It was posted on Thursday, February 27, 2020.

Length: The length is up to you. Shorter is often better.

Title/Tag: When posting your track, please include “disquiet0426” in the title of the track, and where applicable (on SoundCloud, for example) as a tag.

Upload: When participating in this project, post one finished track with the project tag, and be sure to include a description of your process in planning, composing, and recording it. This description is an essential element of the communicative process inherent in the Disquiet Junto. Photos, video, and lists of equipment are always appreciated.

Download: Consider setting your track as downloadable and allowing for attributed remixing (i.e., a Creative Commons license permitting non-commercial sharing with attribution, allowing for derivatives).

For context, when posting the track online, please be sure to include this following information:

More on this 425th weekly Disquiet Junto project — Cellular Chorale / The Assignment: Make music with the source audio from (and inspired by) a Patricia Wolf project — at:

Thanks to Patricia Wolf for collaborating on this project.

More on the Disquiet Junto at:

More on Wolf’s Cellular Chorus at:

https://www.cellularchorus.com/

Subscribe to project announcements here:

http://tinyletter.com/disquiet-junto/

Project discussion takes place on llllllll.co:

https://llllllll.co/t/disquiet-junto-project-0426-cellular-chorale/

There’s also a Disquiet Junto Slack. Send your email address to twitter.com/disquiet for Slack inclusion.

The image associated with this project is a still from a video, provided by Patricia Wolf, of a Cellular Chorus event.

February 26, 2020

Multiple Narratives

Graveyard of Forgotten Gods by NoiseTheorem

A woman’s voice intones the melody of a child’s bedtime song (hence the track’s title, “Lullabye”) amid throbbing synthesized bass and squawking, barely comprehensible (purposefully so) emergency-services chatter. In combination, the elements suggest multiple narratives converging toward tragedy. The same could be said of the album as a whole: Graveyard of Forgotten Gods, a three-track EP from NoiseTheorem, who’s based in Chicago, Illinois. Old-school video-game projectile noises enliven a dubby, spacey, downtempo techno on “Tears for Venus,” which conjures up the likelihood that someone managed to recreate a didgeridoo simulacrum inside of a hacked Second Life account (and just so there’s no ambiguity: that’s meant as a compliment). And on “Song for Ellie,” a gothy procession of dark beats and whirly effects finds the tiniest glimmer of hope in a gentle keyboard motif.

Get the full set at noisetheorem.bandcamp.com. More from Noise Theorem at noisetheorem.com and soundcloud.com/noisetheorem. (The voice on “Lullabye” is Janet Kownacki’s.)

February 25, 2020

Join a Cellular Chorus

Chances are you have more than one internet-accessible device in your home. Gather them together, and pull up the following webpage on each: cellularchorus.com.

Every time you invoke the Cellular Chorus page, a random audio file will be set as the browser’s default. (There are currently 64 different audio files in all.) Then let them play, all of them at once. Move the devices around the room. Don’t let any single device take prominence. Adjust the volume accordingly. Use the pulldown menu or the forward/back buttons to alternate between tracks. Note how the same file will sound different on your rattly old tablet than it does on your brand new laptop, how your humble kitchen speaker can’t hold a candle to your bleeding-edge smartphone.

Now dim the lights. Each instance of sound comes with its own shade of gradated color, like a little handheld Olafur Eliasson installation. Let them illuminate the room. Also note how the sounds work together. This is due to the planning and intent of Patricia Wolf, the Portland, Oregon-based musician who came up with Cellular Chorus, which she describes as “a work of spatialized aleatoric music using smartphones to bring people physically closer to have an interactive and collective experience with light and sound.” (The website was designed and developed by Jaron Heard.)

“The sounds I made are meant to harmonize,” she notes on the site’s info page. “There is no right or wrong way to play them.” Many of the tracks are drones, some electronic in origin (like number 5), others employing the human voice (12). Some (like number 9 and 34) are percussive.

In an email to me, Wolf explained a bit more about the project’s origin, about how the cold Northwest winter inspired her to employ a tool of online social activity, the smartphone (hence the name of the piece), to bring people together in person.

So now use one of your devices to get in touch with some friends. Have them over, and get them all to use cellularchorus.com at once, together.

More from Patricia Wolf at instagram.com/patriciawolf_music, where recent videos have highlighted footage of the Cellular Chorus in action, and at soundcloud.com/patriciawolf_music. More from Jaron Heard at jaronheard.com.

February 24, 2020

Where Industrial and Ambient Meet

session one by Ariana van Gelder & Ars Troitski

There are spaces where industrial music and ambient meet. One such space exists where the drone of archaic, mechanized activity joins up with a concern less for the routinization of modern life, and more for the machinery itself. It’s less about, perhaps, the metronomic pulse of life, and instead more about the underlying hum of activity. Beats go by the wayside as an aesthetic affection for rust, for the texture of a grinding gear, for the serrated whir of equipment takes control. This is the industrial ambient of the first side of Session One, the album a pair of lengthy tracks (17 and nearly 13 minutes each) by Ariana van Gelder and Ars Troitski. Presumably Session One isn’t a split single — that, instead, the two musicians are acting in tandem, or at least trading files toward a singular, collaborative whole. The first side is a rich, slowly evolving soundfield, through which various airborne irritants make their conflicting paths, leading to a whorl of action in what might seems, on first listen, to be a portrait of stasis. The flip side (neither has a name, save “side a” and “side b”) is where a more familiar rendering of industrial rears its gearhead. After a slow build, it is all heavy klang, though even here the klang is still more about volume and power than about tempo. Gorgeous stuff.

Album originally posted at pomusic.bandcamp.com. P.O. is a record label based in Moscow, Russia. More from Ariana van Gelder at

arianavangelder.com (I didn’t locate a link for Ars Troitski).

February 23, 2020

Listened to While Listening

I receive three PR emails for music recordings. Which of these would I be least likely to check out?

A link to an audio stream.

A downloadable press kit with audio files.

A link that first alerts me that my email and IP address will be saved, processed, and forwarded to the “product owner.”

Understand that there are days when I get hundreds of such emails.

For the record, it’s #3: I see no need to grant approval for email and IP address alignment and tracking simply to listen to an advance recording. (Even if it is one of my favorite musicians — and experience has shown that in such rare cases, an email request from me will allow me to bypass the digital protections because, ultimately, the publicist is glad to have found someone interested.)

Once upon a time, bushels of CDs arrived, at great expense, the cost put on the artist, onerously and not always transparently. Now, today, when sending a digital file costs virtually nothing, there is, in some PR corners, a need perceived to track the personal information of the listener. Or, in the best of circumstances, an anonymized data cluster showing generalized habits.

I suppose that this way the PR agency can report data back to the artist, but the data doesn’t register the varied interest of people who simply opt out because such tracking is just an even more invasive branch of DRM (digital rights management, the thing you don’t have to concern yourself with if you download music from Bandcamp or SoundCloud).

The resulting data doesn’t even matter because PR doesn’t exist to tell artists whether or not (anonymous?) individuals are listening to the work. The PR exists to help the musicians get the word out. Anything to the contrary is specious at best, and counterproductive at worst. One needn’t be listened to while listening.

If as a recipient of such PR requests, you refuse such tracking, you get a word sent back the other direction: These practices are invasive and unnecessary. I’d rather wait until the music is out and be, heaven forbid, “late.” And the fact is, there’s plenty (vastly more) to listen to that isn’t secreted behind a veil of invasive protection. That’s where I’ll spend my listening time.

This Week in Sound: Bracelet of Silence + …

This is lightly adapted from an edition first published in the February 17, 2020, issue of the free Disquiet.com weekly email newsletter This Week in Sound (tinyletter.com/disquiet).

As always, if you find sonic news of interest, please share it with me, and (except with the most widespread of news items) I’ll credit you should I mention it here.

“I know the microphone is constantly on,” said one computer scientist to the other. They are spouses, and the microphone in question was in their home. So while much of society routinely accepts domestic surveillance as the price of convenience, Ben Zhao and Heather Zheng set out to find a solution, and in the process developed a “bracelet of silence” (much tidier than the old Get Smart cone), though still somewhat clunky, like the severed arm of a robot octopus. “[T]he bracelet has 24 speakers that emit ultrasonic signals when the wearer turns it on. The sound is imperceptible to most ears, with the possible exception of young people and dogs, but nearby microphones will detect the high-frequency sound instead of other noises.”

“I know the microphone is constantly on,” said one computer scientist to the other. They are spouses, and the microphone in question was in their home. So while much of society routinely accepts domestic surveillance as the price of convenience, Ben Zhao and Heather Zheng set out to find a solution, and in the process developed a “bracelet of silence” (much tidier than the old Get Smart cone), though still somewhat clunky, like the severed arm of a robot octopus. “[T]he bracelet has 24 speakers that emit ultrasonic signals when the wearer turns it on. The sound is imperceptible to most ears, with the possible exception of young people and dogs, but nearby microphones will detect the high-frequency sound instead of other noises.”

“A new kind of red light is going viral — one that stays red as long as drivers keep honking their horns.” If you follow the noise-pollution beat, you know that no English-language reporting amasses more coverage than that originating in India. Mumbai has taken a highly tactical approach to the problem: “The police hooked a decibel meter to the signal and said if the decibel level went over 85, the red light would get longer.” (Factoid side note: “Mumbai and Manhattan don’t even crack the top five noisiest cities, according to the World Hearing Index: ‘Guangzhou, China, ranked as having the worst levels of noise pollution in the world, followed by Cairo, Paris, Beijing and Delhi.'”)

“A new kind of red light is going viral — one that stays red as long as drivers keep honking their horns.” If you follow the noise-pollution beat, you know that no English-language reporting amasses more coverage than that originating in India. Mumbai has taken a highly tactical approach to the problem: “The police hooked a decibel meter to the signal and said if the decibel level went over 85, the red light would get longer.” (Factoid side note: “Mumbai and Manhattan don’t even crack the top five noisiest cities, according to the World Hearing Index: ‘Guangzhou, China, ranked as having the worst levels of noise pollution in the world, followed by Cairo, Paris, Beijing and Delhi.'”)

“Square’s acquisition of Dessa comes after the financial tech company snatched up Eloquent Labs, a conversational AI services business founded by two leading natural language processing researchers.” AI startups are sometimes described as technologies in search of solutions. The company Dessa, born DeepLearni.ng, specializes in deepfakes, both visual and audio, and has been acquired by Square, the financial technology company led by Twitter’s CEO, Jack Dorsey.

“Square’s acquisition of Dessa comes after the financial tech company snatched up Eloquent Labs, a conversational AI services business founded by two leading natural language processing researchers.” AI startups are sometimes described as technologies in search of solutions. The company Dessa, born DeepLearni.ng, specializes in deepfakes, both visual and audio, and has been acquired by Square, the financial technology company led by Twitter’s CEO, Jack Dorsey.

“Google has started adding an incredibly error-prone automatic punctuation feature to its voice typing input method that can’t be turned off, and it’s driving. People. Nuts.” If you’ve ever tried to insert punctuation with voice technology, you know the drill. Google has tried out a solution, but it’s. Causing. More problems. Than perhaps were. Expected.

“Google has started adding an incredibly error-prone automatic punctuation feature to its voice typing input method that can’t be turned off, and it’s driving. People. Nuts.” If you’ve ever tried to insert punctuation with voice technology, you know the drill. Google has tried out a solution, but it’s. Causing. More problems. Than perhaps were. Expected.

“For X-Files fans and nerdy boys n’ girls who’ve crushed on Anderson for decades, it might all be too much.” Gillian Anderson has recorded ASMR to promote her new comedy, Sex Education.

“For X-Files fans and nerdy boys n’ girls who’ve crushed on Anderson for decades, it might all be too much.” Gillian Anderson has recorded ASMR to promote her new comedy, Sex Education.

“A telescope in Canada has found a source of mysterious fast radio bursts that repeat every 16 days, according to a new paper. It’s the first regularly repeating fast radio burst known to science.” The signal’s origin is reportedly about half a billion light-years away from Earth, so you have time to re-read Childhood’s End.

“A telescope in Canada has found a source of mysterious fast radio bursts that repeat every 16 days, according to a new paper. It’s the first regularly repeating fast radio burst known to science.” The signal’s origin is reportedly about half a billion light-years away from Earth, so you have time to re-read Childhood’s End.

“Your personality’s central organ is your voice”: That’s one of numerous sentences that volunteers must repeat as part of a Northeastern University project to “donate their voices” for use by others who lack their own voices: “For someone who has never been able to speak due to conditions like cerebral palsy or severe autism, VocaliD can blend a donated voice with the nonverbal sounds from a recipient to create a personalized voice that represents what that person would sound like if she could speak.”

“Your personality’s central organ is your voice”: That’s one of numerous sentences that volunteers must repeat as part of a Northeastern University project to “donate their voices” for use by others who lack their own voices: “For someone who has never been able to speak due to conditions like cerebral palsy or severe autism, VocaliD can blend a donated voice with the nonverbal sounds from a recipient to create a personalized voice that represents what that person would sound like if she could speak.”

When the Oscars were being broadcast last weekend, I didn’t pay a lot of attention. I was cooking dinner. When someone called out the nominees for a given category, I’d take an educated guess as to who might win. That’s how the Oscar game is played. But when it came time for the best composer, I said I would guess not who I thought would win, but who I wanted to win: Hildur Guonadottir. Then her name was announced (for Joker), and I screeched loud enough to alarm the neighbors. She was the first woman to win in nearly a quarter century. Last year was a blockbuster for Guonadottir, who also did the music for the HBO series Chernobyl. (Forgive me for not including the accent marks, but at the moment the third letter in Guonadottir breaks my website’s content management system. I’ve been looking into it.)

When the Oscars were being broadcast last weekend, I didn’t pay a lot of attention. I was cooking dinner. When someone called out the nominees for a given category, I’d take an educated guess as to who might win. That’s how the Oscar game is played. But when it came time for the best composer, I said I would guess not who I thought would win, but who I wanted to win: Hildur Guonadottir. Then her name was announced (for Joker), and I screeched loud enough to alarm the neighbors. She was the first woman to win in nearly a quarter century. Last year was a blockbuster for Guonadottir, who also did the music for the HBO series Chernobyl. (Forgive me for not including the accent marks, but at the moment the third letter in Guonadottir breaks my website’s content management system. I’ve been looking into it.)

February 22, 2020

The Music of Tentacle

Finally, this afternoon, finished reaching the short but dense and complex novel Tentacle by Rita Indiana (originally La mucama de Omicunlé), in a translation by Achy Obejas. I started it just over a month ago, and it’s the sort of book you read two chapters at a time, let them sink in, and then read some more.

Indiana is also a musician, and it shows on the page. There isn’t a heap of music in the book — there’s more contemporary art in this dystopian future — but when Indiana employs music in her story, as she does toward the novel’s end for a climactic party sequence, she locates a vibrant kinship between hybridized popular culture and the book’s more trenchant themes: Santeria, gender fluidity, and ecological collapse.

How We Listen

How we listen to music in 2020 differs significantly from how it was 10, 20, 30 years ago. And it differs from how we’ll listen in the future, doubtlessly. Over at an online, public discussion board where I regularly participate, someone introduced a conversation about how we listen right now. My initial sense was I listen on varied services today, whereas during the distant past of relative youth my listening was more unified. Then I began to do some forensics — that is, I thought before I typed my contribution to the discussion — and what I found differed from what I expected:

The Past: When I was growing up, I listened through four main ways: (1) the AM/FM radio in my bedroom, (2) the boombox cassette player (later with an LP player hooked into it) in my bedroom, (3) my parents’ LP/cassette player in the living room, and (4) MTV on the living room television. (Eventually a cassette Walkman and a CD player joined the mix. And later on: a CD Walkman.)

The Present: I set down that list to contrast it with the present. By definition, the present is more in flux than the past. These days, I note, it’s easier to categorize my listening habit by technology than by location. Someone replied in that same discussion that the transition “from place-based listening to product-based listening” is worth reflecting on. I agreed: I think the phone and the laptop are my main sources of distancing from music listening in this regard. Locations have disappeared because there is no spatial distinction. Sitting in the living room without either my phone or my laptop is a luxury I rarely take up — outside the house, even less so. By way of example, I typed my part of that chat on my phone as I walked to the barbershop. (For further example, three people at the barbershop were playing some racing game together on their own phones, as if the barbershop were their living room.) In any case, what follows is where my listening habit stands in mid-February 2020. It may change. It will. And I do need to treat my living room more like a cultural Faraday cage.

Laptop: Browser (SoundCloud, Bandcamp, YouTube, etc.), plus a desktop Google Play Music (GPM gets me ad-free YouTube) application, plus an endless array of files that I have long since failed to keep organized. I play the files in VLC. (I would like something less clunky looking than VLC.) And there’s a CD player hooked up to my laptop, though I use it less to listen directly than to rip files (FLAC, thanks for asking) that I then listen to.

Phone: Same as laptop, minus the files (and less frequent SoundCloud).

iPad: Same as phone. (I have also gotten into setting up wholly unoriginal, very simple generative stuff that I think of as the semi-intentional releases of the software developers, but that’s a side topic.)

Other: Stereo in living room (LP, CD, cassette — though the cassette player is unplugged at the moment due to spatial constraints).

Notable Absence: I don’t really listen to podcasts. This may or may not relate to the fact that I don’t really listen to much music with words/voices in it. I do listen to a lot of audiobooks.

The Future: I am fine listening in lots of different places and formats. To be clear: I’m not really in any major way disappointed in my listening habits. The primary corrective fixation I have is the failed promise of digital files. I have a ton, and do not revisit them the way I do other formats. I want to have a better handle on my file-based listening. I’ve been on the hunt for a good cross-platform (iOS, Android, Windows in my current case, though it’ll inevitably change) options. I sometimes think a standalone portable device is a good idea for me. The MP3 player, once ubiquitous, is now such an antiquated concept that when I ponder it, my brain translates it into “a Kindle for music.” (I don’t have a Kindle. I’m waiting for when the Paperwhite gets the inevitable upgrade to adjustable warm light.) That said, I don’t really want to carry one more thing.

February 21, 2020

Graphic Notation x Visual Code

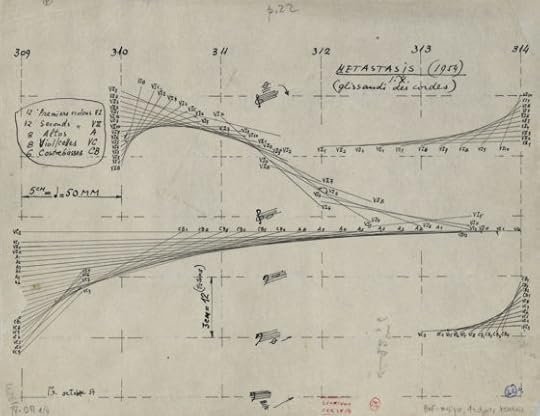

There is a tradition of graphic notation, in which images are read as musical scores, whether or not that’s actually the intended case of the original source — contrast, for example, the beautiful designs of an Iannis Xenakis’ orchestration (below) with the found scores of Christian Marclay (further below).

There is, as well, the growing range of software tools that are, in effect, visual programming languages for sound. They allow the user/composer/coder to create systems — virtual instruments — that then emit audio both planned and discovered, intended and by chance.

In turn, when an implementation of a visual programming language reaches a certain synchrony with the music it produces, the visual can be said to serve double duty: both as virtual instrument and, in effect, as graphically notated score.

This is certainly the case with the vibrant hodge podge, shown up at the top of this post, that constitutes “Generative Music with Modular Synth in Pure Data,” by musician Fahmi Mursyid. As its title suggests, it’s a generative piece (one that produces music that might differ over time) in Pure Data (a programming language originated by Miller Puckette). Listen and watch here (and if you are a Patreon supporter of Mursyid’s, the original post for the track on YouTube includes a link to the Pure Data patch, which you can download, listen to in real time, and tweak as you like).

More on Pure Data at puredata.info. More from Fahmi Mursyid, who is based in Indonesia, at ideologikal.bandcamp.com. (I don’t usually write about the same musician twice in a week, but this piece is quite different from the feedback drone of Mursyid’s I wrote about on Tuesday.)