Marc Weidenbaum's Blog, page 231

June 21, 2020

Current Listens: Sadnoise’s Drones + Note-less Patches

This is my weekly(ish) answer to the question “What have you been listening to lately?” It’s lightly annotated because I don’t like re-posting material without providing some context. In the interest of conversation, let me know what you’re listening to in the comments below. Just please don’t promote your own work (or that of your label/client). This isn’t the right venue. (Just use email.)

▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰

NEW: Recent(ish) arrivals and pre-releases

▰ Femi Shonuga-Fleming records as Sadnoise. The just-released album Droner is far more exploratory and aggressive than its title might suggest. It’s filled with dense atmospheres, yes (numbered “Droner 00” to “Droner 09”), but they generally feel like the listener is on the receiving end of some intense industrial power plant’s exhaust. Which is to say, it’s exhilarating.

▰ Julianna Barwick has a new album due out July 10, and judging by the first two tracks to be made available, “Insight” and “In Light” (the latter featuring Jónsi of Sigur Rós), Healing Is a Miracle is going to be a masterpiece of melted pop, deep in shoegaze territory. Also guesting: Nosaj Thing and Mary Lattimore. Due out on Ninja Tune on July 10.

Healing Is A Miracle by Julianna Barwick

▰ The one downside about Fact Magazine’s Patch Notes series on YouTube is there aren’t actually any patch notes. That peculiar shortcoming aside, the latest is up to the series’ high standard: a solo performance of slow-motion, pastoral ambient from the excellent r beny.

▰ Robert Henke has added another archival bit to his Bandcamp account. Two bits, actually, from 2015. There’s the 90-BPM drones and clangs of “Dolores,” by Anstam (Lars Stöwe), and Henke’s own “VT-100,” antic yet spacious techno recorded entirely using one instrument: the Linn Drum.

Dolores / VT-100 by Robert Henke / monolake

June 20, 2020

On Online Concerts (and Music Plus AI)

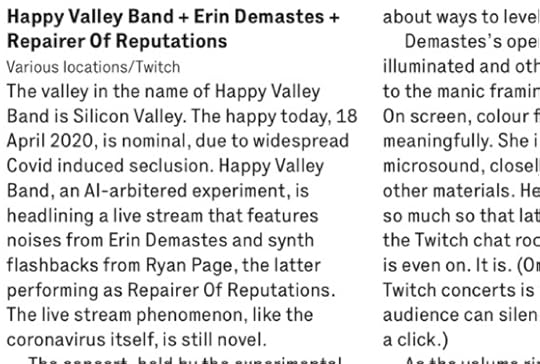

If you’re a curious listener to adventurous music, then you’ll likely recognize this typeface. I wrote a concert review that appears in the latest issue of The Wire (437, the one with Tangerine Dream on the cover, or more specifically a Robert Beatty illustration).

This is the first freelance concert review I have ever written on the same device on which I witnessed the concert. That’s because it was a streaming event, fairly early during the pandemic, two months back on April 18. It was a triple bill put on by Indexical, a non-profit promoter based in Santa Cruz, California, and featuring Happy Valley Band, Erin Demastes, and Repairer of Reputations (aka Ryan Page). Indexical isn’t a venue, per se. Indexical is an opinionated concert promoter making use of various venues. These include a gallery and a production studio, and as of the pandemic, the streaming platform Twitch, as well.

The headliner was quite the Happy Valley Band, who, under the guidance of leader David Kant, perform versions of familiar pop songs transcribed from impressions synthesized by artificial intelligence. During the show Karp characterized what they do as “destroying your favorite songs,” which is about right. In the published review I compare Happy Valley Band to a combination of Kenneth Goldsmith and PDQ Bach (cultural plundering in the service of joking forensic dismemberment). In my draft, I pondered what if David Letterman had replaced David Sanborn on the Hal Willner’s Night Music series: They sound like someone threw the notes off the roof of a building to see what happens when they splatter on the ground. Or, remember those old play-along albums called Music Minus One? On them, one part of a popular piece of music would be removed, so you could play along and feel like a member of the ensemble. The Happy Valley Band is more like Music Plus AI: the original version lingering quietly in the background, a halcyon through-line memory of less complicated times, while the machine-processed rendition stomps through the foreground. All of which said, you have to admire the group’s collective and good-humored commitment to the experiment. (There’s more on Demastes, who played a microsonic set that involved close-up live images of the sources of her audio, and Page, whose work involved fictional found footage, in the published review.)

I didn’t spend much of the review considering the then unique circumstances of the virtual event, based on my sense that (1) I didn’t want to repeat what other reviewers in the same issue might say, given the limited space, and (2) by the time the review was published, this sort of thing would be the norm. At the time, what I was thinking about was how venues and technology create new forms of intimacy (it was pretty nice to be able to just put my feet up on my desk) and memory (all three performances are archived on Twitch: Happy Valley, Demastes, and Repairer). Noise pollution is an old problem in concerts, notably from the chattering class that is fellow attendees. Light pollution rose with the advent of the cell phone. As I mention in the review, the main new irritation here was the venue itself, as Twitch, being aimed at gamers and not at people who want to focus on the performer, has a tendency to draw attention to itself, urging you to level up when you really want to just watch and listen. On the flipside, it was pretty cool to run into a friend from another city (someone I hadn’t seen since 2012) in the chat room, and to catch the name of a musician I admire who happened to show up in the audience.

In any case, pick up the latest issue for the review.

June 19, 2020

Rain Loops

A single tape loop makes its course, round and round. It does so out of one tape recorder and into another and then back to the first again, over and over, or at least over and over for the three minutes and thirty seven seconds of “Rainy Season.” The track is by the always inventive and often, as here, playful Famhi M, or Fahmi Mursyid, who is based in Bandung, Indonesia. The sound of “Rainy Season” is alternately frazzled and desolate, sharp and distant, all thanks to, as Mursyid describes it, the tools employed: “The texture of analogue magnetic tape, high frequency noise, crackle, magnetic particles, and hiss.” The source audio is field recordings, here transformed into a whole other fictional soundscape. Listen with your eyes closes, and get transported. Open your eyes, and appreciate the structural accomplishment, the devices partially disassembled and put to uses far beyond their original engineering, the fragile loop traveling a distance unintended for this archaic material. There’s a connection to be considered between the sound and the structure, between the artifice of the imagined world and the purposeful jury-rigging of the devices.

Video originally posted at youtube.com. More from Fahmi Mursyid at ideologikal.bandcamp.com, soundcloud.com/ideologikal, and fahmi-mursyid.weebly.com.

June 18, 2020

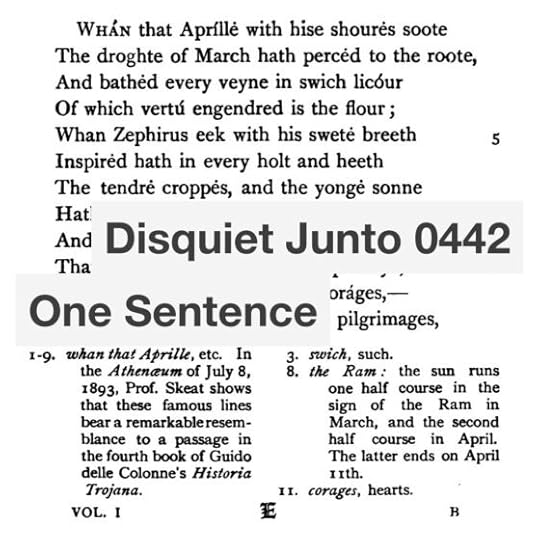

Disquiet Junto Project 0442: One Sentence

Each Thursday in the Disquiet Junto group, a new compositional challenge is set before the group’s members, who then have just over four days to upload a track in response to the assignment. Membership in the Junto is open: just join and participate. (A SoundCloud account is helpful but not required.) There’s no pressure to do every project. It’s weekly so that you know it’s there, every Thursday through Monday, when you have the time.

Deadline: This project’s deadline is Monday, June 22, 2020, at 11:59pm (that is, just before midnight) wherever you are. It was posted on Thursday, June 18, 2020.

These are the instructions that went out to the group’s email list (at tinyletter.com/disquiet-junto):

Disquiet Junto Project 0442: One Sentence

The Assignment: Make music that explores the shape, tone, cadence, and content of a favorite section of prose or poetry.

Step 1: Choose a favorite single sentence. The sentence should be from prose or poetry, but not a song lyric.

Step 2: Say the sentence out loud, slowly, several times in a row. Consider its shape, its tone, its cadence, and its content, and how these connect with each other.

Step 3: In some way that you can understand, map the exploration of the sentence from Step 2.

Step 4: Compose a piece of music that follows the map from Step 3. Note that the finished piece shouldn’t (or better yet: needn’t) include the spoken sentence (that is, it’s best if it’s purely instrumental), and it might last much longer than the sentence would take to say out loud.

Seven More Important Steps When Your Track Is Done:

Step 1: Include “disquiet0442” (no spaces or quotation marks) in the name of your tracks.

Step 2: If your audio-hosting platform allows for tags, be sure to also include the project tag “disquiet0442” (no spaces or quotation marks). If you’re posting on SoundCloud in particular, this is essential to subsequent location of tracks for the creation of a project playlist.

Step 3: Upload your tracks. It is helpful but not essential that you use SoundCloud to host your tracks.

Step 4: Post your tracks in the following discussion thread at llllllll.co:

https://llllllll.co/t/disquiet-junto-project-0442-one-sentence/

Step 5: Annotate your tracks with a brief explanation of your approach and process.

Step 6: If posting on social media, please consider using the hashtag #disquietjunto so fellow participants are more likely to locate your communication.

Step 7: Then listen to and comment on tracks uploaded by your fellow Disquiet Junto participants.

Additional Details:

Deadline: This project’s deadline is Monday, June 22, 2020, at 11:59pm (that is, just before midnight) wherever you are. It was posted on Thursday, June 18, 2020.

Length: The length is up to you.

Title/Tag: When posting your tracks, please include “disquiet0442” in the title of the tracks, and where applicable (on SoundCloud, for example) as a tag.

Upload: When participating in this project, be sure to include a description of your process in planning, composing, and recording it. This description is an essential element of the communicative process inherent in the Disquiet Junto. Photos, video, and lists of equipment are always appreciated.

Download: It is always best to set your track as downloadable and allowing for attributed remixing (i.e., a Creative Commons license permitting non-commercial sharing with attribution, allowing for derivatives).

For context, when posting the track online, please be sure to include this following information:

More on this 442nd weekly Disquiet Junto project, Disquiet Junto Project 0442: One Sentence — The Assignment: Make music that explores the shape, tone, cadence, and content of a favorite section of prose or poetry — at:

More on the Disquiet Junto at:

Subscribe to project announcements here:

https://tinyletter.com/disquiet-junto/

Project discussion takes place on llllllll.co:

https://llllllll.co/t/disquiet-junto-project-0442-one-sentence/

There’s also a Disquiet Junto Slack. Send your email address to twitter.com/disquiet for Slack inclusion.

June 17, 2020

The Search for Intelligent Life

All held chords and cinema-ready dramatics, calculated shimmers and barely perceptible shifts, “OUT∃R WΩRLDS” by composer Dolores Catherino represents a search for intelligent life between the notes. The result bridges the gap between 20th-century classical modernism and classic synth space music. Track originally posted art soundcloud.com/dolores-catherino. More on Catherino at newmusicusa.org.

June 16, 2020

Laraaji Goes Home Again

Laraaji is a name synonymous with the early days of ambient music. But there were days even earlier than those, as a new album makes clear. The musician has long been associated with Brian Eno’s pioneering creation, curation, and collation of ambient music in the 1970s, thanks to the album Ambient 3: Day of Radiance. Since then, Laraaji has been best known for his work with electronically enhanced zither. But on Sun Piano, due out tomorrow, July 17, on the All Saints label, Laraaji sticks with solo piano, reaching back to the musical education that preceded his electronic explorations. Two tracks have been posted so far, the Asia-tinged “Temple of New Light,” and the equal parts soulful and playful “This Too Shall Pass,” with its echoes of Nina Simone’s barroom bravura and Aaron Copland’s Western gravitas. I’ve heard the whole record, and all I can say is his rendition of the folk song “Shenandoah” features a marvel of an arrangement.

Get the album at laraajimusic.bandcamp.com. I interviewed him back in 2015: “The Eternal Life Aquatic with Laraaji.”

June 15, 2020

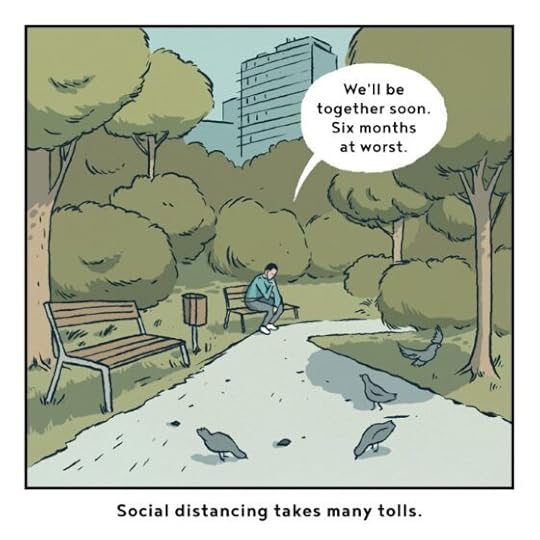

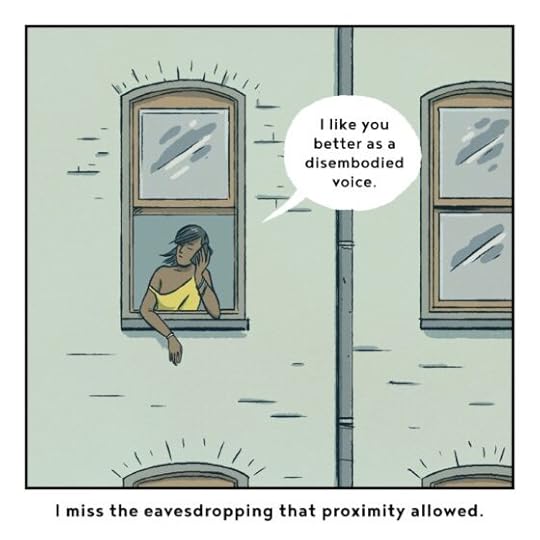

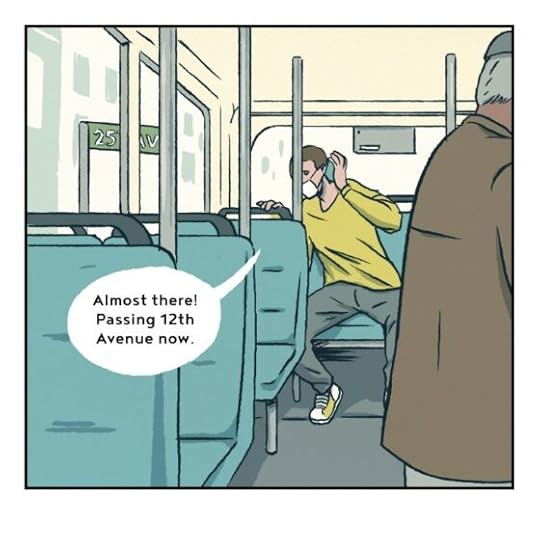

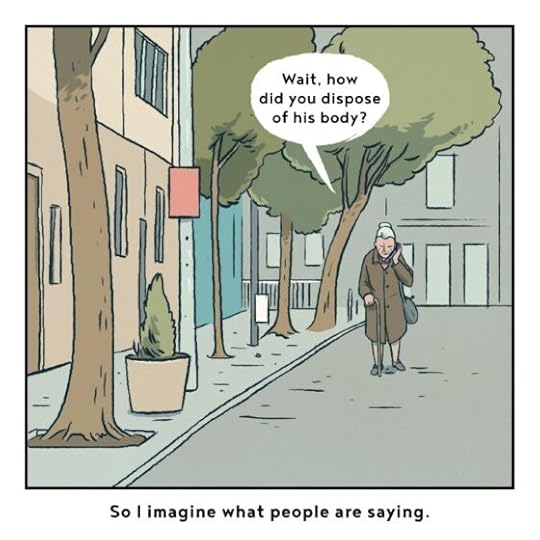

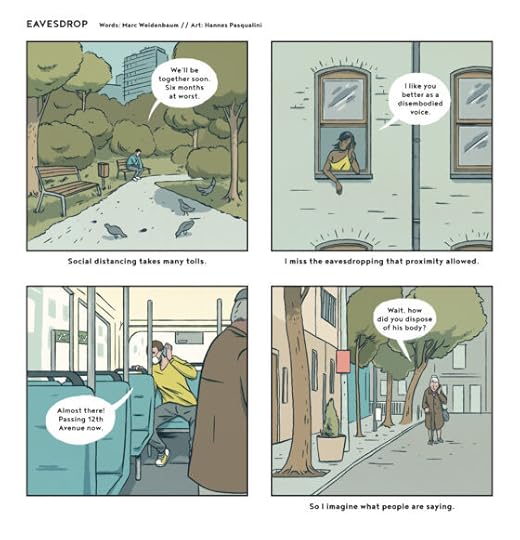

Eavesdrop

. . .

Many thanks to illustrator Hannes Pasqualini (horizontalpitch.com, papernoise.net) for the collaboration. This one is inspired in part by something Vince Keenan wrote during the recent hilobrow.org Decameron.

June 14, 2020

Current Listens: New Hassell, Compiled Underworld

This is my weekly(ish) answer to the question “What have you been listening to lately?” It’s lightly annotated because I don’t like re-posting material without providing some context. In the interest of conversation, let me know what you’re listening to in the comments below. Just please don’t promote your own work (or that of your label/client). This isn’t the right venue. (Just use email.)

▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰ ▰

NEW: Recent(ish) arrivals and pre-releases

▰ Last week digitally enhanced trumpeter Jon Hassell announced a new record, Seeing Through Sound (Pentimento Volume Two), with a single track, “Fearless,” that is everything a longtime fan might hope for, and everything needed to help a novitiate brave the unfamiliar, ever-shifting territory of his glitching, soulful Fourth World. The album is out July 24 on his own label, Ndeya. Pre-order on Bandcamp.

▰ There is a propensity for joy on Markus Floats’ Third Album that is absolutely intoxicating, notably on the the bubbly “Always.” What makes such moments all the more striking is the mass-like seriousness that comprises the majority of this rich, wide-ranging, deeply rewarding collection.

▰ The May 10 Current Listens entry trumpeted a then forthcoming album, Hélène Vogelsinger’s Contemplation, based on the emotional arpeggios of its opening track. The full album came out Friday, and it fulfilled expectations, especially on the vertiginous center track, “Rebirth,” in which rapid-fire pulses pierce a rich, near-ethereal vocal line.

Contemplation by Hélène Vogelsinger

▰ The British duo Underworld released a slew of new material this past year under the title Drift, a constantly expanding collection of experiments that they finally collected into a box set. The box has now been both condensed (in size) and expanded, to collect eight CDs, a Blu-ray disc, and a 50-page booklet, all for about $43 (not including shipping), which seems like quite the deal. The highlight among many highlights is a disc’s worth of collaborations (available separately as well) with the Australian out-there jazz group the Necks, some of my favorite music either group has recorded:

June 13, 2020

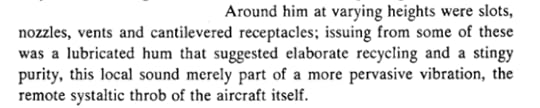

Listening to Ratner’s Star

Having recently reread the most recent Don DeLillo novel, Zero K (2016), I’ve gone back and begun to reread a much earlier one, Ratner’s Star (1976). No doubt as to why I was under the spell of those books for so many years.

For context, the main character is a precocious young mathematician getting to know the soundproof, windowless room at a think tank that is now to be considered home.

June 12, 2020

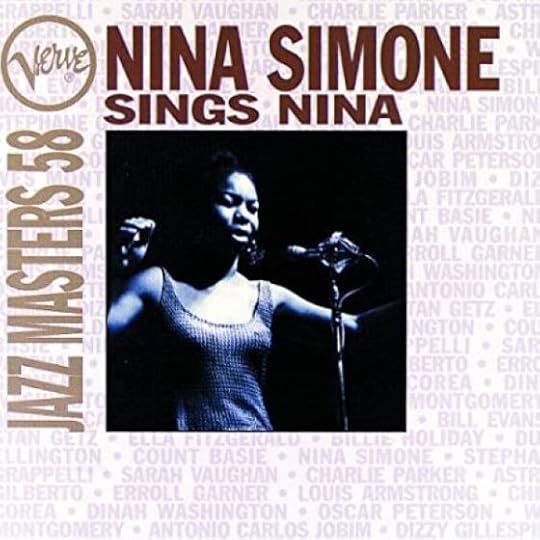

Nina Sings Nina

In 1995 or 1996, when I was an editor at Pulse!, the magazine published by Tower Records, I was the last person in the office one day when the phone happened to ring. It was an editor at the esteemed Verve record label, looking for contact information for one of our frequent contributors. We got to talking and I mentioned my affection for Nina Simone, whose music I was fairly addicted to at the time. He said that the recent compilation in the Verve Jazz Masters series had been such a success that perhaps I should propose a sequel. I proposed two, one of which was the CD I would proceed to sequence and write liner notes for. (The other, which was not picked up, proposed Simone tracks that I felt were optimal for hip-hop producers to sample.)

The album Verve Jazz Masters 58: Nina Simone Sings Nina was released in 1996. I spent an enormous amount of time on it, and remember having to use a cassette deck to tape and then test out various potential sequences of the songs. My liner notes to the album used, I believe, to be on Disquiet.com, but at some point, during one or another transition, disappeared, so I’m finally today, at the end of a long week almost halfway through what will continue to be a very long and arduous year, posting them here.

On the best-loved version of the most famous song she has ever composed, “Mississippi Goddam,” Nina Simone tells her Carnegie Hall audience between verses, “This is a show tune, but the show hasn’t been written for it yet.” She is only half joking. Simone’s writing, for all its majesty, has always seemed incomplete. Rather, her original songs suggest themselves as scraps of something larger, perhaps several things larger — a show, indeed, but also an autobiography, a treatise of gender, a political manifesto.

Perhaps “scraps” is not the best word. Simone’s original songs leave no seams showing, no couplets to be rhymed, no bridges to be built. “Synecdoche” better describes her compositions, meaning the part that signifies the whole, like a fin for a shark or a top-ten single for a career. But such a scholastic term would surely scare off novice fans tickled by her cover of “My Baby Just Cares for Me,” a recording who’s recent appropriation by film and advertising testifies to Simone’s continued appeal.

Yet how else to describe the sense of greater context that halos all of Simone’s songwriting? Isn’t “Four Women,” with it’s innovative modulation between characters, more dramatic than most full-length musical shows? Aren’t her anthems, “Mississippi Goddam” and “Old Jim Crow,” purposely tough acts to follow, their rousing choruses meant to dispatch the audience into the streets? Simone writes each composition as if it were the one she wants on her tombstone. “Sugar in My Bowl” is suggestion, seduction, and recuperation wrapped into one pop song.

Simone’s songwriting is most remarkable for its breadth. She has constructed identities from the music and words of others, as did the generation of jazz vocalists preceding her, but she has also created varied personae in songs she has written, anticipating the autobiographical endeavors of rock’s singer-songwriters. Her concert programs are patchworks sewn from gospel and folk, Broadway and blues. A Simone performance is as likely to be written by her as it is to be written by someone else: She composes in every genre, as if the music business were some artistic decathlon and her songs must compete in each event.

The tunes heard here include gospel (“If You Pray Right (Heaven Belongs to You)”) and pop (“Sugar in my Bowl”). Her political work ranges across the folk music tradition; it can be as comic as Tom Paxton’s (“Go Limp”) or as resolute as Woody Guthrie’s (“Mississippi Goddam”). She adapts texts widely, using the lyrics of a contemporary of Byron, Thomas Moore (“The Last Rose of Summer”), and a figure of Harlem renaissance, Waring Cuney (“Images”).

And no matter what its context, each song carries the scent of autobiography. Her lyrics clearly relate to her public life: to matters of racial tension, social issues, and sexual politics. Furthermore her songs illuminate her musical autobiography, the snatches of Bach and gospel from her childhood, the echo of popular standards of her era, the folk-song agitprop of the civil rights movement.

She is famous for coming to composition by circumstance. As a single young woman supporting herself playing piano, she improvised — for self-preservation, not out of a deep understanding of jazz — to fill out arduous cocktail hours. As the civil rights movement drew her in, she found subject and audience for her unique voice. The alto that tunneled through “I Loves You, Porgy” and the keened Ellingtonia had something of its own to say.

But songwriting has never been the primary focus of Simone’s career, given her talents as a pianist, arranger and, of course, a singer of other composers’ songs. Her own songs generally remain uncovered, though few among the new generation of women in rock and soul haven’t claimed her influence. This must be painful for a woman who has treated the songs of others with such engagement.

In retrospect, Simone’s considerable catalog — in her autobiography more than 40 albums are listed, omitting gray-market titles — effects a false impression of her appreciation of her songwriting. It might seem that she thinks it is secondary to her work interpreting other’s songs: No release on the Philips label, the core of Verve’s Simone holdings, features more than three Simone originals. Many of the Philips -era originals were drawn from the concert she gave in the spring of 1964 in New York City, spread over a handful of albums. The implication is clear: Live, Simone called the tunes, her own well represented on the program. But the record companies chose not to focus on her compositions. It wouldn’t be the only disservice to her done by the music industry.

Verve’s catalog does not fully represent Simone’s writing. There are dozens of other songs (“To Be Young, Gifted, and Black,” “Backlash Blues,” and “I Sing Just to Know I’m Alive” foremost among those missing here). But chosen instead for this compilation are songs closely associated with Simone that she did not write: a traditional gospel (“Take Me to the Water”); one by Rudy Stevenson a longtime member of Simone’s band, who, like her, lives self-exiled in Europe (“I’m Going Back Home”); and a blues by her ex-husband, Andy Stroud (“Be My Husband”), credited on some albums to Simone. She has been fond of medleys since her cocktail-piano days, working her own songs into others’ and sometimes vice versa. Here Simone’s “If You Knew” blends with “Let It Be Me” by Gilbert Becaud, Pierre Declance, and Curtis Mann. On other occasions she has intertwined “If You Knew” with Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s “Mr. Smith.”

This “Mississippi Goddam,” augmented by guitarist Arthur Adams’ sly picking, was taped two decades after Simone’s momentous Carnegie Hall concerts (that “Goddam is on Simone’s Verve Jazz Masters 17) in a bar and grill on the West Coast. There is a certain poignancy to the fact that the woman who mixed gospel tunes and civil rights compositions on the world concert stage would find her own contributions to the protest song converted into the music of cabaret. This turn of events does not diminish Simone’s songwriting. Quite the contrary, it cements a sense that Simone’s fondest admirers quietly appreciate: that Nina sings Nina for fear that on one else will.