Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 65

December 19, 2014

A Silence about Mary

Madonna with Child, Carlo Maratta, c. 1660.

A Silence about Mary | Fr. Charles Kestermeier, SJ | Homiletic & Pastoral Review

Mary is very central to the Gospel’s infancy narratives, but after Cana she almost disappears: we see her in the “Who are my mother and my brothers and my sisters?” passage, at the foot of the cross, and as being present at the Pentecost event, but after that, nothing. Why does Scripture progressively ignore her in this manner, and what are we to make of it?

The first time we meet Mary, Luke describes her as “filled with grace,” and I think it is possible that we do not take that description in a sufficiently strong sense, at least in terms of her lifetime as a whole: the Annunciation is a moment when the Holy Spirit changes her life completely and in a most profound physical sense, but what would her prayer life have been before and after this visit? I don’t think that we could classify her as a mystic—I doubt that she fits any such categories—and yet, she had to be in some sort of constant awareness of God, living in some sort of profound presence to him, at the very least, after this event, and, almost certainly, before it. To judge from the Magnificat, she was clearly filled with at least the scriptural presence of God in the best possible way, but how does she change afterwards?

The infancy narratives give us some idea of who she is as a young mother, at least from the outside. After that, just about anything we might say about her would be pretty much all speculation—but let me offer some ideas anyway.

In the episode of Jesus discussing with the doctors in the Temple, when he is supposedly “lost” there (Lk 2:41-50), note Mary’s expectation that, even at that age, Jesus would still act like a son and would have at least mentioned to her and Joseph that he was leaving home. At this point, the Perfect Man is acting like a perfect teenager; he still needs some polishing. And then, without any other recorded words from Mary or Joseph, we see Jesus simply return to Nazareth with them.

There he grows in “age, wisdom, and grace” until he is about 30, when he begins his mission and shows a completely different kind of awareness, knowledge, and wisdom than he did in the Temple (it is not easy to describe this new mindset in two words). He begins his real mission, not in the Temple with the doctors of the Law, but fairly far from that place in every sense of the word, far from all the activities and attitudes which that site implies, among the common people instead. He has indeed grown, humanly and spiritually, under the tutelage of Mary, and, for at least much of that time, Joseph. They were exactly what Jesus needed as parents.

The Gospel texts show Mary as present to Jesus only twice after that, before she appears at the foot of the cross.

Ridley Scott and Missing the Point of the Book of Exodus

Ridley Scott and Missing the Point of the Book of Exodus | Fr. Robert Barron | CWR blog

Exodus is not telling a story primarily of political liberation (though that is part of it), but rather a story of spiritual liberation from false gods

Exodus is not telling a story primarily of political liberation (though that is part of it), but rather a story of spiritual liberation from false gods

Father Robert Barron is the founder of the global ministry, Word on Fire, and the Rector/President of Mundelein Seminary. He is the creator of the award winning documentary series, "Catholicism"and "Catholicism:The New Evangelization."Learn more at www.WordonFire.org

Ridley Scott’s new film “Exodus: Gods and Kings” features Moses, the Pharaoh, hundreds of thousands of slaves making their way across the floor of the Red Sea, all ten plagues, the burning bush, and even the angel of Yahweh in the form of a petulant eleven year old boy with a British accent.

And yet, the movie is spiritually flat, as though its makers had read the Biblical story but understood precious little of its theological poetry.

Many commentators have focused their critical attention on the portrayal of the angel as an annoyed little boy, but in itself that choice didn’t bother me. Let’s face it: it’s next to impossible to represent God in a cinematically adequate way. For Charlton Heston, the God of Mt. Sinai was a disembodied voice (actually Heston’s own, dramatically slowed down) and flashes of fire. I’m not at all sure that this was better than Ridley Scott’s version, and in point of fact, the weird kid caught something of the unnerving, unsettling, more than vaguely frightening quality of the God disclosed in the Old Testament.

The problem is the way the relationship between Moses and the God of Israel is presented.

From the Red Carpet to Benedictine Habit

From the Red Carpet to Benedictine Habit | K. V. Turley | CWR blog

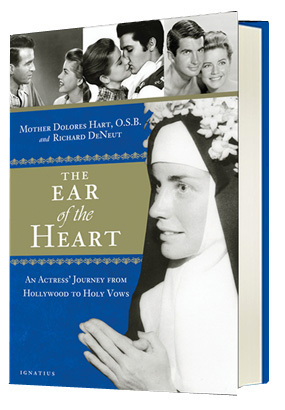

The Ear of the Heart: An Actress' Journey From Hollywood to Holy Vows is a perfect read for this Year of Consecrated Life

Why would a rising Hollywood star leave it all behind and enter a monastery?

The fascinating story is told in full in The Ear of the Heart: An Actress' Journey From Hollywood to Holy Vows (Ignatius Press, 2013), by Mother Dolores Hart, OSB, and Richard DeNeut. It is especially timely during this Year of Consecrated Life, which began on the first Sunday of Advent and concludes on the World Day of Consecrated Life on February 2, 2016.

Even if you haven't heard of Dolores Hart, you have probably seen her. She has the distinction of appearing in not one but two Elvis Presley movies—Loving You and King Creole—as well as many other box office hits. Written, over many years, with Richard DeNeut, a Hollywood PR man (and a former suitor), The Ear of the Heart is part autobiography, part biography.

I first set eyes on Dolores Hart during Christmas 1977 when the BBC showed a season of Presley films following his death earlier that summer. She always played the “good girl” who saves the hero from crime and much worse—often an older siren. Of course, to my 12-year-old eyes, this beautiful actress was welcome to save me too, anytime she liked. And there it stayed for years until I read somewhere she ended up a nun. Stranger things have happened, I thought, but I did wonder how that had come about. Later searches on the internet came up with information as general as it was vague, leaving me none the wiser. So, when I spied this publication of her life story, I ordered and then opened it eagerly, all in the hope it would fill in the gaps. It did. But, what I also found was something much more besides.

For some reason, I expected Dolores to have come from a privileged background, albeit one with heavy doses of Catholicism—a la Grace Kelly—only to find that her upbringing couldn't have been more different. For a start, her mother was almost forced to undergo an abortion once it was discovered she was pregnant with the future star. Thankfully, she refused, and instead, with parents hastily wed, the child lived. That said, the family home was not only not Catholic, but also deeply unhappy. Her father, a handsome but struggling actor, was violent and soon the marriage fell apart. Consequently, young Dolores was constantly on the move, changing both locations and family configurations. Then something truly miraculous happened.

In 1946, aged just eight years old, Dolores decided to become a Catholic. This was even more remarkable given that she had only ended up at the local Catholic school on account of it being the closest to where she was then living. The local priest, however, was initially hesitant. Then Dolores' mother appeared, and told the priest that if he didn't instruct her daughter she would come back and smash every one of his stainglass windows. Dolores was soon after baptised; from then on the book chronicles how her newfound faith became the guiding force in her life.

Her entry into Hollywood was as sudden as had been her conversion.

Continue reading on the CWR blog.

December 17, 2014

"The Theory of Everything": A God-Haunted Film

"The Theory of Everything": A God-Haunted Film | Very Rev. Robert Barron | CWR blog

Why would a scientist assume there is or is even likely to be one unifying rational form to all things, unless he assumed there is a singular, overarching intelligence that has placed it there?

The great British physicist Stephen Hawking has emerged in recent years as a poster boy for atheism, and his heroic struggles against the ravages of Lou Gehrig’s disease have made him something of a secular saint. The new bio-pic “The Theory of Everything” does indeed engage in a fair amount of Hawking-hagiography, but it is also, curiously, a God-haunted movie.

In one of the opening scenes, the young Hawking meets Jane, his future wife, in a bar and tells her that he is a cosmologist. “What’s cosmology?” she asks, and he responds, “Religion for intelligent atheists.”

“What do cosmologists worship?” she persists. And he replies, “A single unifying equation that explains everything in the universe.”

Later on, Stephen brings Jane to his family’s home for dinner and she challenges him, “You’ve never said why you don’t believe in God.” He says, “A physicist can’t allow his calculations to be muddled by belief in a supernatural creator,” to which she deliciously responds, “Sounds less of an argument against God than against physicists.”

This spirited back and forth continues throughout the film, as Hawking settles more and more into a secularist view and Jane persists in her religious belief. As Hawking’s physical condition deteriorates, Jane gives herself to his care with truly remarkable devotion, and it becomes clear that her dedication is born of her religious conviction. Though the great scientist concluded his most popular work with a reference to “knowing the mind of God,” it is obvious by the end of the film that he meant that line metaphorically.

The last bit of information that we learn, just before the credits roll, is that Professor Hawking continues his quest to find the theory of everything, that elusive equation that will explain all of reality. Do you see why I say the entire film is haunted by God?

December 16, 2014

"Tolkien had more to offer than just a really good yarn..."

CBN News correspondent Paul Strand recently talked with Jay Richards, co-author (with Jonathan Witt), of The Hobbit Party: The Vision of Freedom That Tolkien Got, and the West Forgot[image error]

Tolkien had faced horrifying trench warfare himself in World War I and hated the senseless slaughter of war. But he loved liberty even more, so his heroes constantly fought for it in his books.

"The good guys in The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit recognize that sometimes you need to fight, you need to be willing to die," Richards said. "And the cause in every case that they're willing to die for is freedom."

Hobbit-Size Government

Tolkien said he himself was a hobbit in all but size. The Shire where hobbits lived reflected not only his most idyllic childhood hometown, but the way he thought society should run - a place of almost no laws and only a tiny bit of government.

He admitted to his son Christopher in a letter that he leaned towards anarchy and hated the idea of people lording it over other people.

"Tolkien said famously, 'It is the most improper job of any man to boss others, least of all those who seek the opportunity," Richards explained.

Tolkien wrote The Lord of the Rings as he watched his homeland Britain sliding into a soft socialism that was slowly sapping the freedoms of his countrymen.

He was horrified the citizens of the Christian nations would give up their God-given liberty in exchange for security offered by all-powerful governments.

Tolkien could relate to similar concerns expressed by the famed 19th century traveler and writer Alexis de Tocqueville.

After years of keenly observing America, de Tocqueville wrote in 1840s Democracy in America that he feared it and like nations would come under the sway of a future ruling power that would cover "…the surface of social life with a network of petty, complicated, detailed, and uniform rules."

"It does not break men's wills but it does soften, bend, and control them," he wrote.

"Rarely does it force men to act but it constantly opposes what actions they perform," De Tocqueville continued. "It does not destroy the start of anything but it stands in its way; it does not tyrannize but it inhibits, represses, drains, snuffs out, dulls so much effort that it finally reduces each nation to nothing more than a flock of timid and hardworking animals with the government as shepherd."

Tolkien was hopeful art like his could wake people up and shake them up.

Read the entire article, "Tolkien Truth: Giant Lessons from Little Hobbits" (Dec. 21, 2014).

Why God Becomes Human

Compassion, by William A. Bouguereau, 1897.

Why God Becomes Human | Fr. David Vincent Meconi, SJ | Homiletic & Pastoral Review

The Advent and Christmas seasons are upon us. Like the reality itself, we Christians have to look more deeply to see the mystery beneath the glitter and the commotion. God has now descended into his creation to take up his rightful place as Lord and King of Heaven and Earth. He has infiltrated enemy lines in this civil war which rages in each of our divided hearts. In the history of this great battle, only one faithful woman has been his totally. Only she has never strayed, only she has never refused a command, only she is wholly his. The rest of us must be won back through an eternal promise of an eternal labor: Christ’s defeat of sin and death and his extending his life and love in all his elect. This is the great story now made visible in a small cave in Bethlehem. At the center of this scene is Mary, the Mother of God, and in this singular act, she has become the Mother of all God’s children.

And here is where one mystery unfolds into another. Mary intercedes and shares her maternity with all the baptized so that we, too, might bring Christ into the world. Gerard Manley Hopkins thus likened each of us to “New Bethlems,” in whom Christ can once again take on flesh:

Of her flesh he took flesh:

He does take fresh and fresh,

Though much the mystery how,

Not flesh but spirit now.

And makes, O marvelous!

New Nazareths in us,

Where she shall yet conceive

Him morning, noon, and eve;

New Bethlems, and he born

There, evening, noon, and morn.

Our Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches that there are four primary reasons the Word becomes flesh. The first motive for God’s becoming human is to reconcile us to his and to our Father: “The Word became flesh for us in order to save us by reconciling us with God, who ‘loved us and sent his Son to be the expiation for our sins … the Father has sent his Son as the Savior of the world … to take away sins’” (§457) (boldface mine). Death was the result of our divine disobedience, so God himself had to take on that which could die in order to atone for what we mortals incurred. Our Lady gives the immortal Author of Life what he needs to reconcile sinners to the Father, his mortality. This is a great paradox: Mary’s loving God enough to give him whatever he asked from her, not only to the point of death, but even death itself.

The second reason the Catechism gives is epistemological in nature.

December 15, 2014

ISIS, Assad, and What the West is Missing About Syria

Debris is seen inside a badly damaged church in the Monastery of Mar Sarkis in the ancient Christian town of Maaloula, Syria, April 14. (CNS photo/Khaled al-Ha riri, Reuters)

ISIS, Assad, and What the West is Missing About Syria | Alessandra Nucci | CWR

Syria, once home to a unique, multireligious society, is being destroyed. The West is turning a blind eye to the real cause of the tragedy.

Last year Pope Francis called for a day of prayer and fasting for peace in Syria, the Middle East, and the whole world, setting the date for September 7 and himself presiding over a prayer vigil in Rome. In a recent piece for the Wall Street Journal, Peggy Noonan reports that in September of 2013, “the American people spontaneously rose up and told Washington they would not back a bombing foray in Syria that would help the insurgents opposed to Bashar Assad. That public backlash was a surprise not only to the White House but to Republicans in Congress, who were—and I saw them—ashen-faced after the calls flooded their offices. It was such a shock to Washington that officials there still don’t talk about it and make believe it didn’t happen.”

That, of course, was before ISIS, the Islamic State, appeared on the scene, cutting through a third of Syria and Iraq and advancing rapidly, tragically, into the area with the strongest Christian presence in Iraq. A shocked world witnessed the ghastly beheadings of innocent Westerners, along with the displacement, raping, and murdering of Iraqi Christians and Yazidis, the looting and burning down of churches, and the marking out of Christian homes. The leaders of the Western world all vowed to take immediate action. The president of the United States solemnly committed to “degrade and destroy” ISIS. Yet in a matter of months, even the beheadings seem to have receded into the background. It would seem that if you dither long enough, even the most acute world-wide indignation will fade away, as observers become increasingly inured to outrages. Only days after President Obama’s solemn denunciaton, the anti-government Syrian “rebels” announced a deal with ISIS. What for? To join forces against their common enemy: Bashar al-Assad.

Despite a stunning one-time-only admission by President Obama to a delegation of patriarchs in Washington last September—in which he reportedly said, “We know Assad has been protecting the Christians”—the bipartisan attitude towards the Syrian government has continued to hover between aloof and openly hostile.

The depiction of Assad by credible witnesses is quite different. Speaking at a private meeting held at the Veritatis Splendor Diocesan Center in Bologna, Italy last October, Msgr. Giuseppe Nazzaro, former apostolic visitor to Aleppo and former Custodian of the Holy Land, had this to say:

[Assad] opened the country up to foreign trade, to tourism within the country and from abroad, to freedom of movement and of education for both men and women. Before the protests started, the number of women in the professional world had been constantly increasing, the university was open to all, and there was no discrimination on the basis of sex. The country was at peace, prosperity was on the rise, and human rights were respected. A common home and fatherland to many ethnicities and 23 different religious groups, Syria has always been a place where all were free to believe and live out their creed, all relationships were characterized by mutual respect. The freedom that is purportedly being brought to us by the rebels is precisely what this rebellion has taken away from us.

Msgr. Nazzaro was also among the heads of the Churches of the Middle East who were invited to speak at the UN headquarters in Geneva on September 16, where he denounced the “massacres and the atrocities, together with the crimes against humanity” committed by the Islamic State in both Syria and Iraq. The Syrians pinned great hopes on this meeting, but were bitterly disappointed.

December 14, 2014

The Joyful, Particular Scandal of Advent

"Madonna of the Magnificat" (1480) by Sandro Botticelli (WikiArt.org)

The Joyful, Particular Scandal of Advent | Carl E. Olson | CWR

Readings:

• Is 61:1-2a, 10-11

• Lk 1:46-48, 49-50, 53-54

• 1 Thes 5:16-24

• Jn 1:6-8, 19-28

There is something offensive to many people about Advent and Christmas. It is what Apostle Paul described as a “stumbling block” to Jews and Gentiles alike (1 Cor. 1:18-25). Eastern Orthodox philosopher Richard Swinburne calls it “the scandal of particularity.” It is the belief that God became man at a particular time and in a particular place, and that the God-man, Jesus Christ, is the unique Savior of mankind.

“Belief in the true Incarnation of the Son of God,” the Catechism states, “is the distinctive sign of Christian faith” (par. 463). It’s hardly news that this belief is often disparaged or dismissed by some non-Christians. Far more perplexing are attempts by Christians to deny the mystery of the Incarnation by rejecting the singular character of Jesus of Nazareth.

A few years ago, a Catholic priest in Australia posted online a manuscript he had written intending “to allow the man Jesus to be more authentic, and to make our Catholic religion more relevant.” He glibly dismissed the Incarnation, writing, “God is big. Real big. No human being can ever be God. And Jesus was a human being. It is as simple as that!” He then took this denial to its logical conclusion. “For a Christian,” he wrote, “to state that the fullness of redemption and salvation is to be found in Jesus Christ is not an acceptable statement for other faiths or religious traditions. And it is offensive to proclaim it as universal truth.”

Yes, it is offensive. And it is also true! Today’s readings present two great saints who not only proclaimed the truth about Jesus Christ but also gave offense—and continue to give offense—by being faithful to Him. They share in the “scandal of particularity,” for they are closely united to Jesus, by both love and by blood.

The first is John the Baptist, who is always a central figure during Advent. Today’s Gospel reading places a very Johannine emphasis on testimony, or witness. The Greek word—martyria—for “testify” or “witness” is also the root word for “martyr,” and it appears over 25 times in the Fourth Gospel, as well as several times in the Book of Revelation.

This testimony “to the light” is a sure declaration of truth by one who has seen what he gives witness to. The Apostle John, in his first epistle, wrote about “what we have heard, what we have seen with our eyes, what we looked upon and touched with our hands concerns the Word of life,” and then stated, “we have seen it and testify to it and proclaim to you the eternal life that was with the Father and was made visible to us.” He had seen Jesus Christ in person. But John the Baptist had not only seen and known the Savior, he had recognized him while still in the womb (Lk. 1:41). He gave witness not only by word but also by deed: first, through preaching and baptism, then through martyrdom (Mk. 6:17-29).

The second saint is the Theotokos, the Blessed Virgin Mary. She causes scandal to some by her humility and her willingness to accept, in faith, an astounding message from God. She is a stumbling block to many because she, a lowly Jewish maiden, is the Mother of God; her womb was the Tabernacle of the Most High. Her proclamation, the Magnificat—part of it heard today during the responsorial—is the testimony of the perfect disciple: “My soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord; my spirit rejoices in God my savior.”

Many people believe that religious doctrine—especially dogmas about Jesus Christ—leads to narrow-mindedness, bigotry, and even violence. In reality, it is the wellspring of joy, as Mary’s canticle amply demonstrates. It is not enough to simply believe, or to proclaim—we are also called to rejoice and to worship. “Rejoice always,” Paul writes to the Christians in Thessalonica, “Pray without ceasing. In all circumstances give thanks.” Why? “For this is the will of God for you in Christ Jesus.”

Such is the joyful, particular scandal of Advent.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the December 14, 2008, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

December 13, 2014

An "Exodus" Plagued by Extravagant Mediocrity

An "Exodus" Plagued by Extravagant Mediocrity | Nick Olszyk | CWR

Ridley Scott's telling of the story of Moses has numerous flaws. Better to read the Good Book instead.

MPAA Rating: PG-13

USCCB Rating: NR

Reel Rating:

(2 out of 5)

(2 out of 5)

There are several film and television adaptations of the story of the Exodus and subsequent events—most notably, of course, Cecil B. DeMille's classic 1956 epic, The Ten Commandments—so director Ridley Scott had to do something distinct with Exodus: Gods and Kings. Unfortunately, aside from one interesting (but not positive) development, most of the film’s 150 minutes consists of a rehashing of old approaches and a reworking of ideas that covered many times already.

Granted, these do come with some pretty awesome special effects, although the parting of the Red Sea is still better in DeMille’s version, despite being produced almost sixty years ago, with obvious technical limitations. In short, Exodus isn’t a bad movie, just one that’s better enjoyed on DVD, with doughnuts, while writing a high school religion paper comparing the biblical account to the cinematic re-telling.

The first half is almost verbatim a combination of The Ten Commandments and Dreamworks' animated 1999 feature, The Prince of Egypt. Like Commandments, Scott paints an epic world of towering statues, brilliant costumes, and exotic accents. Like Prince, Moses (Christian Bale) and Ramses (Joel Edgerton) were raised together “as close as brothers,” then gradually grow apart when a closely guarded secret is discovered.

Many good actors have played Moses, including Charlton Heston, Val Kilmer, and Mel Brooks. Bale’s prophet is a pragmatic general who puts his faith in knowledge and skill rather than the Egyptian religion.

December 12, 2014

A Delectable Fruit of the Cactus for the Eagle

A Delectable Fruit of the Cactus for the Eagle | Paul Badde | Chapter One of María of Guadalupe: Shaper of History, Shaper of Hearts

With wood from the Santa Marla, Christopher Columbus built the first house in America. Hernán Cortés conquered Mexico. The growling of dogs on the beach and the dawn of the modern era lie heavy over the cities of New World and Old.

On the morning of August 3, 1492, sails billowing in the first wind, Columbus sailed from Andalusia in the Santa María, together with the Niña and the Pinta, in order, as he confides in the ship's log, to search for a westerly sea route to Jerusalem. If the names of his ships had been listed in another  way, they would have made the phrase "Holy Mary (Santa María)paints (pinta) the girl(niña)". In itself, this would have been striking. However, this was only the beginning of the incredible story of the dark Lady, who, five hundred years after the discovery of America, still waits to be discovered by Europe, Asia, Africa and other parts of the world.

way, they would have made the phrase "Holy Mary (Santa María)paints (pinta) the girl(niña)". In itself, this would have been striking. However, this was only the beginning of the incredible story of the dark Lady, who, five hundred years after the discovery of America, still waits to be discovered by Europe, Asia, Africa and other parts of the world.

Historians say that, on Christmas night, 1492, theSanta María ran aground on a sandbar off of Haiti. Columbus decided to dismantle the grounded flagship and "build a fort out of what was salvaged". However, some years ago on the docks of the port of Barcelona, I saw an exact reproduction of the caravelSanta María. I doubt that with the planks and masts of this nutshell anyone could have managed to construct a fort. Two or three huts, perhaps, or a house—or even a small barricaded chapel. There was not enough material for more. The one thing that seems sure is that from the remains of the Santa María the first European house was raised in the New World. A year later it was pulled down and reduced to ashes.

Twenty-seven years later Hernán Cortés, a native of the city of Medellin, in Spain, disembarked from the Santa María de la Concepción onto the shore of the American continent. It was Good Friday of 1519, in the area of what would later become the port of Veracruz. A small expeditionary flotilla accompanied theSanta María de la Concepción . Two days later, Cortés asked two Franciscans, Diaz and Olmedo, to celebrate Easter with a high Mass on the beach. "The Spaniards planted a cross in the sandy ground", writes Francisco López de Gómara in his history of the conquest of Mexico. "They prayed the rosary and the Angelus as a bell was rung." To anyone familiar with Catholic liturgy, this seems somewhat confused. But there is no doubt that, after the liturgical service, Cortés, in a brief speech, took possession of an immense territory in the name of the Spanish Crown. Needless to say, the king of Castile was totally ignorant of who Cortés was and what he was doing there. The "Captain General" had taken on himself the responsibility of a royal commission.

Thus he resembled the immortal Don Quixote de la Mancha, who in Cervantes' book, written years later, would assume the fight against the forces of evil and defend the honor of the pure and lovable Dulcinea, who unfortunately existed only in the poor knight's addled brain and overheated imagination. But, unlike Don Quixote, "the Knight of the Woeful Countenance" with his nag Rocinante and his rusty lance, Cortés set upon his mission with a sharp sword and well-fed horses. Hernán Cortés' countenance was by no means woeful; he was an elegant man who dressed in silk and velvet . The natives could not comprehend what he might represent, and they observed in wonder the solemn ceremony of the occupation of Mexico. They were baffled as they observed these pale, well-armed men bow their heads and kneel before a wooden cross.

Along the coast, next to the conqueror's flagship, were anchored three other caravels and six small brigatines that had transported 530 men in the prime of their lives. They were natives of Spain, Genoa, Naples, Portugal and France. Among them were fifty sailors, the two Franciscans already mentioned, thirty crossbow-men and twelve harquebusmen. Among their armaments the expeditionary force had many swords and lances, sixteen horses, numerous Irish wolfhounds and mastiffs, ten long-range cannons, four falconets and various small Lombard cannons, as the new firearms were named in those days. Some of the men had mutilated ears—the punishment for those who had been caught robbing and convicted in Castile. Be that as it may, the gold chain around the neck of the self-proclaimed Captain General Cortés bore a medal with the Virgin Mary on the front and Saint John the Baptist on the back. On the mainmast of the flagship waved a golden pennant with a blue cross and the Latin inscription: "Amici, sequamur crucem, et si nos fidem habemus, vere in hoc signo vincemus": Friends, let us follow the cross . If we believe in it, truly in this sign we will conquer.

In spite of everything, a few weeks later, some of the conquistadors no longer held such a belief and had lost faith in the leader's good luck; they mutinied and took over a brigantine in order to sail back to Cuba. Cortés hanged two of the ringleaders, mutilated the foot of a third and had the rest publicly flogged. Then he gave orders that, with the whole expeditionary force looking on, nine ships should be grounded in the bay of Villa Rica, in order that even the most cowardly among them would have only one way open, through all their fears: the road to Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital. In those days it was as large and as populated as ancient Naples or Constantinople and was even more beautiful than Venice. Cortés left only one ship in navigable condition, the Santa María de la Concepción. As all of this was going on, in far-away Europe Leonardo da Vinci was dying and the seven German electors were electing Charles I of Castile as Charles V of that Holy Roman Empire over which, it would later be said, the sun never set. With the addition of Mexico and the Philippines, this empire would cover the globe.

Within a mere two years of disembarking, Cortés had conquered the mighty Aztec empire. According to one variant, the word "Mexico" meant the "Land of the Moon". An actual conquest of the moon would not have come as a greater surprise. Nothing could have prepared the Europeans for the discovery of a New World or for the natives, whose human sacrifices terrified and revolted the Spanish adventurers from the first moment they witnessed the Aztecs take a flint knife to carve out the heart of a living victim and place it, still beating, on a black basalt altar as an offering to their god Quetzalcóatl. They called this the "delectable fruit of the cactus for the Eagle". Some of these altars of sacrifice to the Eagle still exist. After the conquest of Mexico, for example, the architects of the royal chapel nearby in Cholula imported them as holy-water fonts for the entryway.

Generally, before the sacrifice of members of the aristocracy, a drink of hallucinogenic mushrooms and a ration of obsidian wine would be given them—something, however, not disdained by many of the onlookers as well, whose deafening roars of laughter echoed unforgettably through the Spaniards' heads day and night. Less aristocratic or reluctant victims received nothing and were dragged up the pyramid by the hair. Because the priests drew blood from their own ear lobes as additional sacrifices, they were sinister-looking indeed. This was not all. They dressed in black; their hair was tangled; their faces ash-gray; their fingernails extravagantly long. Nothing could reconcile the Spaniards to Aztec sacrificial practices: not gold, not plaintive chants, not the gorgeous feathered vestments, not even the legendary magnificence of the Aztec cities. The blood-encrusted temple pyramids seemed to the Spaniards the very portals of hell.

In turn, to the Aztecs, the Spaniards' horses, which they called deer, seemed "as tall as the rooftops". The Spaniards entertained themselves by terrorizing the people with the horses' neighing, which they used tactically and strategically. This was a clash of cultures for which there was no precedent: Stone Age versus Iron Age; obsidian and flint versus Toledo steel; hauling by sled or teams versus the wheel; arrows versus gunpowder and cannonballs; and finally, the recklessly bold spirit of these Renaissance Christians versus the proverbial pagan anguish of the Amerindians, who were subject to an uncountable multitude of gods.

During the conquest of Mexico, from among the 1600 Spaniards, mostly latecomers to Cortés and his expedition, about one thousand died. But the Amerindian tribes who joined the conquistadors—the Tlaxcaltecans, for example, whom the Spaniards stirred up and set against the tyrannical Aztec people—mourned many more victims. The historian Hugh Thomas concludes about their combatants and victims as a whole that the Aztecs "had fought like gods" in the struggle but, in such an unequal contest, had perished by the hundreds of thousands. There had been prophecies that, in the year 1519, Quetzalcóatl, their feathered serpent-god, would return. The Aztecs had been waiting for him for generations. For this reason, some suppose that the Aztecs succumbed, not so much because of Spanish astuteness and their superior war machine, but rather because of an overwhelming surprise—and a profound disappointment.

Before and after the conquest of Mexico, not a single native Amerindian living on the islands of the Caribbean survived the Spanish invasion. For this reason, after their land was conquered, the situation seemed equally hopeless to the inhabitants of Mexico—Mexican, Mistecan, Cholulan, Toltecan, Chichimecan, Tlaxcaltecan, Xochimilcan, Totonacan and others. From here on we will refer to them simply as Aztecs, the name by which the Europeans identified the Amerindians who held sway over vast territories in Mexico at the time of the conquest. First, obviously, no dialogue between the cultures was likely to have been successful, even before the final victory of the military expedition, after Cortés kept the powerful ruler of Mexico, Montezuma II, under arrest in his own palace. Before he died under a rain of stones hurled by Aztec hands, a rain of stones that would erupt like a volcano against the Spaniards from their capital—before all this, the adventurer from Spanish Extremadura would sit for hours at night with the Aztec emperor, who before his accession to the throne had himself been high priest. He spoke to him not only about his sovereign, Charles, the sharpest "sword of Christendom" (to whom Cortés hoped to offer Montezuma's empire as a gift), but also about the ever-virgin Mother of God; about God: the Father, Son and Holy Spirit; about the Immaculate Conception; about the Incarnation; and about many other "interesting things". The sermons of this passionate conquistador and ladies' man were scarcely less bold than his conquest. This is something that sometimes surprises his biographers, and they refer to it frequently.

Nevertheless, for the Aztecs these sermons must have sounded more than strange. For on other days, in the plaza of the Great Pyramid, Cortés permitted the chained Aztec monarch to preside at the solemn burning of rebel Amerindian rulers. Montezuma himself did not stop having human sacrifices offered even while imprisoned. From the apex of the Great Pyramid drums sounded, as did conch horn, flutes and fifes made from bone. The earth had to keep revolving, and for this blood was needed. Also the many celebrations had to continue, and these could not be imagined in ancient Mexico without the human sacrifices that were "like flowers for the gods". The Aztecs had surrendered to bloodlust. The Florentine Codex relates that when his daughter reached the age of six or seven, an Aztec father would say to her: "An obsidian wind is blowing on us; it brushes us lightly and moves on; the earth is not a place of well-being; here there is no joy; here there is no happiness." Four hundred years later, Joseph Hoffner wrote: "A dark and bloody harshness weighed down the religion, a harshness that had deprived them of any cheerful lightness of heart." The Aztecs could not imagine life without war.

In the Old World, on the other hand, especially in Spain, not only were many real or presumptive heretics being burned at the stake, but also, in Germany, this was the time when the Reformation rose and took its course, which for the first time broke the Church apart into Catholics and Protestants, so that very soon eight million Christians had cut themselves off from Rome. No bonfire, no auto-da-fé,with its flames, could stop this revolution. In any event, the Emperor Charles V had enough to worry about without preoccupying himself with the adventures of one of his many foolhardy subjects in some faraway New World. The dawn of the modern era, with its attendant terrors, was on the horizon.

Simultaneously something occurred in Mexico that sounds more fantastic than the most sensational account of the conquest of the Aztec empire by Cortés and his men. It was the first apparition of the Queen of Heaven in the New World. No one with any regard for his intelligence would want to put faith in this phenomenon. Perhaps only now can the scope of this event be truly seen, because, better than ever before, we can now perceive how greatly this event has changed the course of history and the balance of the world.

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles and Book Excerpts:

• Mary in Byzantine Doctrine and Devotion | Brother John M. Samaha, S.M.

• Fairest Daughter of the Father: On the Solemnity of the Assumption | Rev. Charles M. Mangan

• The Blessed Virgin in the History of Christianity | John A. Hardon, S.J.

• "Hail, Full of Grace": Mary, the Mother of Believers | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• Mary in Feminist Theology: Mother of God or Domesticated Goddess? | Fr. Manfred Hauke

• Excerpts from The Rosary: Chain of Hope | Fr. Benedict Groeschel, C.F.R.

• The Past Her Prelude: Marian Imagery in the Old Testament | Sandra Miesel

• Immaculate Mary, Matchless in Grace | John Saward

• The Medieval Mary | The Introduction to Mary in the Middle Ages | by Luigi Gambero

• Misgivings About Mary | Dr. James Hitchcock

• Born of the Virgin Mary | Paul Claudel

• Assumed Into Mother's Arms | Carl E. Olson

• The Disciple Contemplates the Mother | Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis

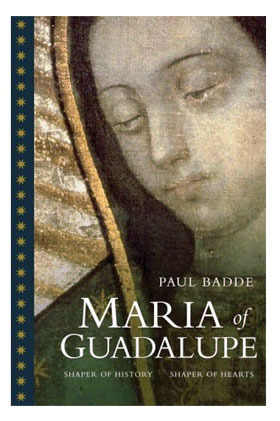

María of Guadalupe: Shaper of History, Shaper of Hearts

by Paul Badde

Mexico, December 9, 1531. Ten years after the Spaniards conquered this land, on a hill on the outskirts of the capital, something inconceivable happens to Juan Diego, a native of the area. At dawn a heavenly figure comes to meet him, revealing herself as "Mary, mother of all men". To confirm the first vision, the Lady not only entrusts him with several messages. But, also, in the final vision, leaves her portrait mysteriously present on his tilma. It is the portrait of a young woman looking downward. She is clothed in a dress figured with roses and a mantle spangled with stars.

From the time of its occurance this event has moved people. However, because of the fascination with the image itself, doubts have been raised, causing some to reject it altogether. This image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, along with the Shroud of Jesus in Turin, have possibly become the most mysterious images on earth. The more studies are made of the image and of the cloth, the more mysterious it all becomes, for believers and scientists alike.

In a hands-on investigation, Paul Badde has been delving into this mystery from a historian's point of view, but also with the growing wonder of a journalist who has stumbled across a fabulous treasure.

In this heartfelt report, Paul Badde tells the fantastic story of the apparition that changed the history of the world. Only in light of this mysterious event, can one explain why the inhabitants of Central and South American entered the Church so quickly. Mary of Guadalupe was the person who inserted a whole continent into Western Culture.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers