Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 55

February 20, 2015

Will the Other Sleeping Giant Awake?

Left: St. Peter's Basilica (us.fotolia.com | © rudi1976); right: Muslim militants (us.fotolia.com | © Oleg_Zabielin)

Will the Other Sleeping Giant Awake? | William Kilpatrick | Catholic World Report

Despite widespread slaughter of Christians and other religious minorities in Muslim lands, the Church currently seems unable to mount any kind of resistance to Islamic ideology

It is often said that when Admiral Yamamoto ordered the attack on Pearl Harbor, he awakened a sleeping giant. Even though the Nazis had occupied much of Europe, bombed London, and advanced to the outskirts of Moscow, the United States was still slumbering on the morning of December 7, 1941.

Although we were aiding the anti-Nazi forces through Lend-Lease shipments and other forms of support, isolationist sentiment remained strong in America. The mood of complacency was succinctly captured in the 1942 wartime film Casablanca:

Rick: If it’s December 1941 in Casablanca, what time is it in New York?

Sam: What? My watch stopped.

Rick: I bet they’re asleep in New York. I bet they’re asleep all over America.

America woke up, but barely in time. Our allies were in disarray, a major part of our Pacific fleet lay at the bottom of Pearl Harbor, and the Wehrmacht was well-armed, well-trained, and highly experienced. Another year of delay and the fate of Europe might have been sealed, and our own future made that much more uncertain.

The Cold War which followed on the heels of World War II kept America on its toes for four more decades, but after the fall of the Soviet system, the sleeping giant resumed its slumber. Then came September 11, 2001—an attack which cost more American lives than Pearl Harbor. It was a classic wake-up call. And for a while, the giant awoke. The American homeland went on high alert and forces were mobilized to attack the enemy’s base in Afghanistan. However, with the relatively easy defeat of the Taliban and Saddam Hussein, the sleeping giant rolled over and went back to sleep. There seemed to be no more threat to our homeland and no serious threat to our military. As a result, the Army is being shrunk to pre-World War II levels, and the Navy to pre-World War I size. Meanwhile, social experimentation has become all the rage. Concern over the strength of the military has taken a back seat to concern over its sensitivity to diversity.

Because we went back to sleep, the Islamic threat to the world is significantly greater today than it was on September 11, 2001. Al-Qaeda is stronger than ever and active in numerous countries. ISIS controls large parts of Syria and Iraq, millions in Africa live in fear of Boko Haram and Al-Shaabab, Afghanistan looks like it will return to Taliban control, Iran will soon have nuclear weapons, and Turkey, with the second largest army in NATO, appears to have more sympathy for radical Islam than for its NATO allies.

America, the sleeping giant, may yet wake up again, but even if it does, it’s not at all clear that it’s up to the task of combating the ideology that fuels the fighting. The war with Islamic militants is both an armed conflict and a culture war. Some of the militants fight with machine guns and mortars, and some fight using weapons of propaganda and political intimidation. But the most powerful weapon that the jihadists wield is religion. The promises made by Islam to young warriors bring in the recruits, and the fact that Islam is a religion keeps the critics away. Islamic ideology is immune from criticism in a way that Nazism and Communism never were.

The other sleeping giant

And that is where the other sleeping giant comes in. I refer, of course, to the Catholic Church.

February 19, 2015

Reading Sacred Scripture and the Catechism Together

The inspiration for the publication of "The Didache Bible" was an address given by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger/Pope Benedict XVI, shown here in an October 2008 photo. (CNS photo/Max Rossi, Reuters)

Reading Sacred Scripture and the Catechism Together | Liam Ford | Catholic World Report

An interview with Rev. James Socias of the Midwest Theological Forum about The Didache Bible: Ignatius Bible Edition

The Didache Bible (RSV, Second Catholic Edition): Ignatius Bible Edition, recently published by the Midwest Theological Forum with Ignatius Press, is a 1960-page study Bible featuring extensive commentaries, based on the Catechism of the Catholic Church, for each of the books of the Bible. The Didache Bible also includes over 100 apologetical inserts, over two dozen full-color biblical maps, and a 43-page glossary and a topical index. Rev. James Socias, Vice President of the Midwest Theological Forum, spoke recently about what inspired the creation and publication of The Didache Bible and how it can be used by Catholics for group and individual study.

Why did Midwest Theological Forum decide to publish the Didache Bible?

Fr. Socias: The primary inspiration for the Didache Bible was the address given by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, now Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, in 2002 on the tenth anniversary of the publication of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. In this address, Cardinal Ratzinger strongly advocated the use of Scripture in the Catechism as a means to explain the faith and emphasized how it was important to read Scripture within the living tradition of the Church.

While the Catechism has greatly benefitted from its many references to Sacred Scripture, we found it surprising that there was nothing that would allow the reader to go the other way around; that is, a Bible with commentaries that referenced the Catechism. Such a Bible would facilitate a better understanding of how a particular verse or verses are directly related to the teachings of the Catholic Church.

In reflecting on this, we came to see that a Bible with commentaries based on the Catechism would be a good companion to the Didache Series textbooks, which are also based on Scripture and the Catechism. This, in effect, was our inspiration to publish the Didache Bible.

What is the importance of consulting the Catechism when reading the Bible?

Fr. Socias: As Cardinal Francis George says in the preface, the Second Vatican Council “affirmed the importance of Sacred Scripture in the life of faith.” The Deposit of Faith, which is contained in Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition, is safe-guarded and transmitted by the Magisterium of the Church, and the Catechism is the basic summary of this great wealth of Catholic teaching. Catholics who desire to understand the faith more completely will naturally want to study the Catechism and read the Bible on a regular basis.

By basing the commentaries on the Catechism and by referencing the relevant parts Catechism, the Didache Bible provides the reader with a means to better understand how the teachings of the Church are based on Scripture and how the living tradition of the Church interprets those verses of Scripture.

How does the Didache Bible respond to the Second Vatican Council’s call to renew the Catholic faith in the modern world?

February 18, 2015

Great Lent

Great Lent | Thomas Howard | From Evangelical Is Not Enough: Worship of God In Liturgy and Sacrament | Ignatius Insight

Presently Lent arrives. This is the forty days leading up to Easter, which also recall the forty days of Christ's temptation in the wilderness. There is a telescoping of things here, since His temptation did not in actual fact immediately precede His Passion, but "liturgical time" is such that spiritual significance may override chronological exactness.

Lent, like Advent, is a time of penitence. Here we identify ourselves with the Lord's fast and ordeal in the wilderness, which He bore for us.

This raises a point worth noting in passing. There are some varieties of Protestant theology and spirituality that so stress "the finished work of Christ" and the fact that He accomplished everything, that they leave no room at all for any participation on our part. Such participation, encouraged by the ancient Church, does not mean that we mortals claim any of the merit that attaches to Christ's work, much less that we can by one thousandth particle add to His work. Nevertheless, the gospel teaches us that Christians are more than mere followers of Christ. We are His Body and are drawn, somehow, into His own sufferings. We are even "crucified" with Him.

My own tradition stressed this, but it was taught as a metaphor that meant only the putting to death of sin in our members. There was very little said about the sense in which Christ draws His Body into His very self-giving for the life of the world and makes them part of this mystery. Saint Paul uses extravagant language about his own filling up "that which is behind of the afflictions of Christ." We had succinct enough explanations as to what he might have meant here, but these explanations allowed no room for any notion of our participating in Christ's offering. This was looked upon as heresy, violating the doctrine of grace .n which all is done by God and nothing by us. We are recipients only. That the gracious donation of salvation by God could in any manner include His making us a part of it all, as He made the Virgin Mary an actual part of the process, and as Saint Paul seems to teach, was not the note struck.

The ancient Church, in its observance of Lent, once more asks us to move through the gospel with Christ Himself. The most obvious mark of Lent to a newcomer is the matter of fasting. I had own about this practice all my life. My Catholic playmates would give up chocolates or Coke or ice cream for Lent. I also knew that a few devout people in my own tradition of evangelicalism practiced fasting now and again for special purposes—a time of especially concentrated prayer, for example.

I myself thought of Lenten fasting and also of the old Catholic practice of refusing meat on Fridays as being legalistic, and perhaps even heretical, since it seemed to entail some notion of accruing merit. Since Christ had done all, why should we flagellate ourselves this way? Was it not a return to the weak and beggarly elements condemned by Saint Paul? Was it not to be guilty of the very thing that the apostle had a sailed the Galatian Christians for?

I discovered that the ancient Church teaches just what the New Testament teaches on the point, namely, that fasting is a salutary thing for us to undertake. Jesus fasted and assumed that His followers would. "When ye fast," He said, not "if." Saint Paul both practiced it and taught it. It seems to constitute a reminder to u that our appetites are not all and that man shall not live by bread alone. Furthermore, if we may believe the universal testimony of Christians who do practice it, it also clarifies our spiritual vision somehow. Lastly, it is a token of the Christian's renunciation of the world. There is no thing that a Christian will insist he must have at all costs. Fasting supplies an elementary lesson here.

Lent asks us to ponder Christ's self-denial for us in the wilderness. It draws us near to the mystery of Christ's bearing temptation for us in His flesh, and of how in this Second Adam our flesh, which failed in Adam, now triumphs.

Lent also leads us slowly toward that most holy and dread of all events, the Passion of Christ. What Christian will want to arrive at Holy Week with his heart unexamined, full of foolishness, levity, and egoism? To those for whom any special observances hint of legalism or superstition one can only bear witness that the solemn sequence of Lent turns out to be something very different from one's private attempts at meditating on the Passion. To move through the disciplines in company with millions and millions of other believers allover the world is a profoundly instructive thing.

Lent begins with Ash Wednesday. The first time ashes were imposed on my forehead, I found a cacophony of voices inside me: "Come! Now you have betrayed your background! This is straight back to the Dark Ages. Fancy Saint Paul's doing this!"

I knew it was not so when the priest came along with the little pot of damp ashes and with his thumb smudged my forehead—my forehead, the very frontal and crown of my dignity as a human being!—and aid, "Remember, O man, that dust thou art and unto dust thou shalt return."

I knew it was true. I would return to dust, like all men, but never before had mortality come home to me in this way. Oh, I had believed it spiritually. But surely we need not dramatize it this way....

Perhaps we should, says the Church. Perhaps it is good for our souls' health to recall that our salvation, far from papering over the grave, leads us through it and raises our very mortality to glory. We, like all men, must die. I felt the strongest inclination to wave the priest past as he approached me in the line of people kneeling at the rail. Not me—not me—like Agag coming forth delicately, hoping that the bitterness of death was past. Yes, you. Remember, O man....

I was beginning to learn that when we encounter some "spiritual" truth in our bodies, it is brought home to us. We can meditate on suffering all day long, for example, but let us have migraines, and we know something we could not have known through merely mulling over the doctrine of suffering. We can meditate on love all day long, but let us kiss the one we long for, and we know immediately something we could not have known if we had thought about love for a thousand years. Nay—our very salvation came to us in the body of the incarnate God. "O generous love! that He who smote/In Man for man the foe,/The double agony in Man/For man should undergo," says Cardinal Newman's hymn. The ashes effected something in me more than a smudge on my forehead. I had felt, if only for a moment, the thing that I wished most earnestly to be exempted from: death.

• Thomas Howard biography

• Thomas Howard Books Published by Ignatius Press

• Interviews and Book Excerpts

Related Ignatius Insight Articles:

• Lent: Why the Christian Must Deny Himself | Brother Austin G. Murphy, O.S.B.

• The Old Age and the New | Thomas Howard | From Chance or the Dance?

• "I never thought I wanted to be a writer" | An Interview with Dr. Thomas Howard

• Catholic Spirituality | Thomas Howard | From The Night Is Far Spent

• Reading T.S. Eliot's "Four Quartets" | An Interview with Dr. Howard about Dove Descending: A Journey Into T.S Eliot's Four Quartets

• Thomas Howard and the Kindly Light | An Interview with Dr. Howard about his book, Lead, Kindly Light

• An Hour and a Lifetime with C.S. Lewis | An Ignatius Insight Interview with Dr. Thomas Howard

• "Tradition" | Chapter 14 of On Being Catholic | Thomas Howard

• The Quintessential – And Last – Modern Poet | Fr. George William Rutler | The Foreword to Dove Descending: A Journey Into T.S. Eliot's Four Quartets, by Thomas Howard

Thomas Howard was raised in a prominent Evangelical home (his sister is well-known author and former missionary Elisabeth Elliot), became Episcopalian in his mid-twenties, then entered the Catholic Church in 1985, at the age of fifty. He is an acclaimed writer and scholar, noted for his studies of Inklings C.S. Lewis ( Narnia & Beyond: A Guide to the Fiction of C.S. Lewis) and Charles Williams (The Novels of Charles Williams), as well as books including Christ the Tiger, Chance or the Dance?, Hallowed be This House, Evangelical is Not Enough, If Your Mind Wanders at Mass, On Being Catholic, The Secret of New York Revealed, and Lead, Kindly Light: My Journey to Rome, the story of his embrace of Catholicism, and Dove Descending: A Journey Into T.S. Eliot's Four Quartets. Visit his IgnatiusInsight.com author page here.

Thirsting and Quenching

Thirsting and Quenching | Fr. Thomas Dubay, S.M. | From Prayer Primer: Igniting a Fire Within

Men and women everywhere are hungry and thirsty, voraciously yearning and seeking: rich and poor, wise and foolish, young and old, literate and illiterate, saints and sinners, atheists and agnostics, playboys and prostitutes. Some can explain their inner emptiness in words; most cannot, but everyone experiences it. That inner ache drives all our dreams, desires, and decisions--good and bad. Even your decision to pick up this book and read was triggered by this nameless desire.

Our abiding hunger for more than we presently experience does not have to be  proved but only explained. Which is what we propose to do right now, before we even begin to think about what prayer is all about. Otherwise you and I cannot understand fully the splendid reality of communing deeply with our Creator and Lord and of our unspeakable destiny in and with him.

proved but only explained. Which is what we propose to do right now, before we even begin to think about what prayer is all about. Otherwise you and I cannot understand fully the splendid reality of communing deeply with our Creator and Lord and of our unspeakable destiny in and with him.

Mere animals do not and cannot have this inner aching need, for the simple reason that material things are satisfied with visible creation and their place in it. Because you and I have intellects and wills rooted in our profound spiritual core, nothing finite and limited does, or ever can, fill us. Deep in our humanness is an ache for fullness, for infinity. We are completely satisfied by no individual egoism, by no series of selfish pursuits: vanity, fame, money, lust, power, drugs. Always the sinner seeks more accolades, more money, more recognition, more lewd eroticism, more control of others, more drugs. Never is he satisfied, never really happy and fulfilled.

Why is this so? As spirit-in-the-flesh beings, you and I burst beyond the material order, beyond what our senses can attain, beyond the cosmos itself. By its limited nature nothing created can satisfy us. God alone, the sole infinite One, can fill our endless yearnings. As Karl Rahner put it, we are oriented by nature to the Absolute. Or as John Courtney Murray expressed it, the problem now is not how to be a man, but how to become more than a man. Or as St. Augustine put it in his classic prayer: "You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they rest in you." Kittens and giraffes do not have this problem. They cannot. You and I do. (See CCC 27-30.)

Quenching and prayer

What does this have to do with a primer on prayer? Much, very much. Prayer is not merely a pious reaction to suffering or a means to get us out of trouble. We are the only beings in visible creation who cannot attain fulfillment without becoming more than we are, therefore without the divine. Ducks and camels, trees and stars need matter alone. In other words, you and I are transcendent beings whose needs go beyond this universe. That is why our destiny must be God and no one else. That is why prayer is absolutely basic. This is the divine plan, and no other plan comes close. At the heart of our human reality there must be a relationship and communion with the divine. Otherwise we simply do not make it; we do not and cannot flourish and attain our destiny. (See Evidential Power of Beauty, pp. 17-20.)

Prayer, therefore, is both simple and deep--and, as we shall see later on, immensely enriching, leading to unspeakable love and delight. Prayer is not complicated, because there is nothing more natural than to converse with your beloved, and most especially with your supreme Beloved. If all grows normally it becomes deep, because, as we have explained, it is rooted in your profound human and spiritual reality, in who and what you are as a man or a woman.

The illness of boredom

But we need to look at all this from another point of view, the downside of our human situation. Among the saddest pictures we meet in life is a jaded face: the visage of one who "has done it all", whose life through wanton sin is a shambles; It is a countenance that expresses no joy, no peace, no excitement, no enthusiasm, no interest, no hope, no love, no fulfillment. Behind that face is an inner desert of degenerate exhaustion, completely empty of lively delight.

[image error]

Jadedness is extreme boredom, but there are lesser degrees, of course. But even lesser shadings are abnormalities. Human beings are meant to be alive and vibrant, full of wonder, love, and happiness-which is exactly what Scripture promises to those who embrace God's word fully. This is what the saints experience, what people who have a deep prayer life know to be the case. They "rejoice in the Lord always", not just some of the time (Phil 4:4).

Jadedness and boredom and an absence of vibrant prayer comprise one reason among others that the great novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky was right on target when he made the comment that "to live without God is nothing but torture." Not everyone admits this, of course. One reason is pathological denial. Another is that when people are so submerged in self-centered pleasure seeking, they cannot see what some silence and solitude and honesty would make obvious to them. A third explanation for the denial is that bored people often use pleasures, both licit and illicit, as so many narcotics that tend to dull the deep inner pain of their emptiness. This human aching is always lurking in the center of their being, but it is faced only in honest silence. The print and electronic media offer endless proof day after day that Dostoevsky was right, but few care to see and to listen. Facing reality as it is requires honesty. As Jesus himself put it: We cannot serve both God and mammon (Mt 6:24). If it is not the first, it will be the second. Nature abhors a vacuum.

This famous novelist went on to remark that atheists should actually be called idolators. Why? When one rejects the real God, he inevitably substitutes lesser things to fill his inner emptiness. Everyone, we should notice, has one or more consuming interests that occupy his desires and dreams. If we are not captivated by the living God and pursuing him, we will center our desires on idols, big or small: vanities, pleasure seeking, prestige, power, and others we have already noted. While the idols never it isfy, they often do serve as narcotics that more or less deaden the inner pain of not having him for whom we were made and who alone can bring us to the eternal ecstasy of the beatific vision.

Yes, if you and I are not seriously pursuing the real God, inevitably we will focus on things that can never satisfy us. We are chasing after dead ends. Prayer is the path to reality/Reality.

Quenching at the fountain

Scripture says it best of all. With a charming invitation the Lord shouts "Oh, come to the water all you who are thirsty; though you have no money, come .... Why spend money on what is not bread, your wages on what fails to satisfy .... Pay attention, come to me; listen, and your soul will live" (Is 55:1-3, JB). Nothing less can bring us to life. And Isaiah himself keeps vigil through the night as his spirit yearns for his Lord (Is 26:9). He practices what he proclaims.

The psalmist is of like mind: his soul thirsts for the living God (Ps 42:2-3). Like a parched desert he pines for his Lord, for only in him does he find rest (Ps 63:1; 62:1). The inspired writer knows that God must be our consuming concern, for pursuing him, adoring him, loving him, being immersed in him can alone profoundly delight and fill us. Anything less than Everything is not enough.

The New Testament has the same message, for the Fountain has appeared in the flesh. He declares in the Sermon on the Mount that they are blessed who hunger and thirst after holiness (Mt 5:6), and his Mother proclaims in her Magnificat that the Lord fills the hungry with every good thing (Lk 1:53). Jesus explicitly invites all those who are thirsty to come to him for a quenching with living water (Jn 7:37). At the very end of both Testaments this same invitation is extended to everyone: let all the thirsty come forward to be forever quenched with the life-giving waters, that is, an eternal enthrallment in Father, Son, and Holy Spirit seen face to face (Rev 22:17).

Prayer life is therefore profoundly rooted in the needs of our human nature. Without it we are frustrated creatures. All the way from the beginnings in vocal prayer through meditation, which leads to the summit of contemplation, this prayerful immersion in the indwelling Trinity gradually transforms us from one glory to another as we are being turned into the divine image (2 Cor 3:18). Here alone do men and women become "perfect in beauty" (Ezek 16:13-14). We can understand why Henri de Lubac was prompted to say that man is truly man only when the light of God is reflected in a face upturned in prayer.

Prayer Primer: Igniting A Fire Within

Prayer Primer: Igniting A Fire Within

Fr. Thomas Dubay, a renowned teacher and writer on prayer and the spiritual life, presents a simple, profound and practical book on the most important of all human activities, communion with God.

Prayer Primer is written for intelligent adults (and teenagers) who want God and a serious prayer life, but it does not presuppose that they need or have a theological background. It does take up many questions rarely answered adequately in the classroom or from the pulpit, often not mentioned at all: Why pray? (be ready for some surprises) ... Why vocal prayer is important and yet should be limited ... What contemplation is and is not ... Praying with Scripture ... Family prayer--even how to introduce children to group meditation ... Prayer in a busy life ... Pitfalls and problems--together with solutions ... Buddhism? New Age? Centering prayer? ... What should you do when dry and empty and not at all inclined to pray? How do you even get started? ... Where and how to begin? ... Assessing progress ... Growing in depth. All of these subjects, and more, are clearly and concisely explained for citizens of this 21st century.

"Of the many books written on prayer, Prayer Primer is unique. Father Dubay is a master on this subject. It is a rare gift to have a simple primer written by such a man. It is utterly sound, trustworthy and practical." -- Peter Kreeft, Author, Prayer for Beginners

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles and Book Excerpts:

• St. John of the Cross | Fr. Thomas Dubay, S.M.

• Seeking Deep Conversion | Fr. Thomas Dubay, S.M.

• Designed Beauty and Evolutionary Theory | Fr. Thomas Dubay, S.M.

• The Source of Certitude | Fr. Thomas Dubay, S.M.

• "Lord, teach us to pray" | Gabriel Bunge, O.S.B.

• The Confession of the Saints | Adrienne von Speyr

• Catholic Spirituality | Thomas Howard

• The Scriptural Roots of St. Augustine's Spirituality | Stephen N. Filippo

• The Eucharist: Source and Summit of Christian Spirituality | Mark Brumley

• Liturgy, Catechesis, and Conversion | Barbara Morgan

• Blessed Columba Marmion: A Deadly Serious Spiritual Writer | Christopher Zehnder

Fr. Thomas Dubay, S.M., is a well-known retreat master and expert in the spiritual life.

Fr. Thomas Dubay, S.M., is a well-known retreat master and expert in the spiritual life.

A Marist Priest, Father holds a Ph.D. from Catholic University of America and has taught on both major seminary level for about fifteen years. He spent the last twenty-seven years giving retreats and writing books (over twenty at last count) on various aspects of the spiritual life.

Ignatius Press has published several of his books, including Fire Within, Happy Are The Poor, Faith and Certitude, Authenticity, The Evidential Power of Beauty, and Prayer Primer. He has presented many series on EWTN, including an extensive study of the spiritual life of St. Teresa of Avila and a series on the life of prayer.

Lent: Why the Christian Must Deny Himself

Lent: Why the Christian Must Deny Himself | Brother Austin G. Murphy, O.S.B. | IgnatiusInsight.com

We still ask ourselves as Ash Wednesday approaches, "What am I doing for Lent? What am I giving up for Lent?" We can be grateful that the customs of giving up something for Lent and abstaining from meat on Fridays during Lent have survived in our secular society. But, unfortunately, it is doubtful that many practice them with understanding. Many perform them in good faith and with a vague sense of their value, and this is commendable. But if these acts of self-denial were better understood, they could be practiced with greater profit. Otherwise, they run the risk of falling out of use.

A greater understanding of the practice of self-denial would naturally benefit those who customarily exercise it during Lent. Better comprehension of self-denial would also positively affect the way Christians live throughout the year. The importance of self-denial can be seen if we look specifically at fasting and use it as an example of self-denial in general. Indeed, fasting, for those who can practice it, is a crucial part of voluntary self-denial.

But since we live in a consumerist society, where self-indulgence rather than self-denial is the rule, any suggestion to fast will sound strange to many ears. It is bound to arouse the questions: Why is fasting important? Why must a Christian practice it? Using these questions as a framework, we can construct one explanation, among many possible ones, of the importance of self-denial.

To answer the question "Why must the Christian fast?" we should first note that fasting, in itself, is neither good nor bad, but is morally neutral. But fasting is good insofar as it achieves a good end. Its value lies in it being an effective means for attaining greater virtue. And because it is a means for gaining virtue– and every Christian ought to be striving to grow in virtue–there is good reason to fast.

Some people point out that fasting is not the most important thing and, therefore, they do not need to worry about it. Such reasoning displays a misunderstanding of our situation. But, since the excuse is common enough, some comments to refute it are worthwhile.

Doing Small Things Well

First, while it is true that fasting is not the most important thing in the world, this does not make fasting irrelevant or unimportant. There are, certainly, more urgent things to abstain from than food or drink, such as maliciousness, backbiting, grumbling, etc. But a person is mistaken to conclude that he therefore does not need to fast. He should not believe that he can ignore fasting and instead abstain in more important matters. Rather, fasting and avoiding those other vices go hand in hand. Fasting must accompany efforts to abstain in greater matters. For one thing, fasting teaches a person how to abstain in the first place.

Moreover, it is presumptuous for a person to try to practice the greater virtues without first paying attention to the smaller ones. As Our Lord says, "He who is faithful in a very little is faithful also in much" [1] and so can be trusted with greater things. Therefore, if a person wants to be able to abstain in greater matters he must not neglect to abstain in smaller matters, such as through fasting.

Finally, there is a subtle form of pride present in the person who says that because something is not very important, he does not need to do it. Whoever makes such a claim implies that he does only important things. But the average person is rarely called to do very important things. Accordingly, each person is more likely to be judged on how he did the little, everyday things. Even when, rarely, a person is called to do a great work, how often does he fall short? All the more reason, then, for a person to make sure that he at least does the small things well. Furthermore, if he truly loves the Lord, he will gladly do anything–big or small–for him. So, in the end, saying that fasting is not the most important thing is not a good excuse for avoiding it.

What, then, is the reason for fasting? To answer this let us first clarify what fasting entails. It involves more than the occasional fast, such as on Good Friday. To be effective, fasting requires disciplined eating habits all the time. There are certainly days when a person should make a greater effort at abstaining from food and drink. These are what we usually consider days of fasting and they must be practiced regularly. But, still, there are never days when a person is allowed to abandon all restraint. A person must always practice some restraint over his appetites or those periodic days of fasting arc valueless. Always keeping a check on his desires, a person develops good habits, which foster constancy in his interior life. So, in addition to practicing days of fasting on a regular basis, a person should continuously restrain his desires, such as those that incline him to eat too much, to be too concerned with what he eats, or to eat too often. [2]

We might, then speak of the discipline of fasting in order to avoid the impression that fasting is sporadic. The operative principle behind the discipline of fasting is simple: to limit yourself to only what is necessary for your physical and psychological health–no more, no less. St. Augustine puts it concisely when he teaches: "As far as your health allows, keep your bodily appetites in check by fasting and abstinence from food and drink." [3] So, fasting is meant only to keep a person's unnecessary wants in check. A person is not– nor is he permitted–to deny himself what is necessary for his health. The discipline of fasting instead asks a person to check his desires for what is superfluous and not necessary.

Realizing True Well-being

Consequently, fasting should not threaten a person's health. And there is no foundation for believing that fasting is somehow motivated by anti-body sentiments. Fasting actually does good for the body by helping it realize its well-being. The body needs to be in conformity with the spirit and this requires such disciplines as fasting. In this way, the body is like a child. Children would never realize their true well-being if their parents never told them "no," but gave in to every one of their desires. In the same way, if a person never says "no" to his bodily desires, his body will never realize its true well-being. That is, the body needs such discipline to be brought into conformity with the spirit. For otherwise, it cannot share in the spiritual blessings of Christ.

This makes perfect sense when we consider that the human person is not just a soul, but is matter as well. A person’s body, too, is to be renewed in Christ. Fasting is one way that a person brings about a harmony between body and soul, so that being made whole he can be one with Christ.

The Christian belief that the body is intimately united to the soul should also make a person suspicious of the opinion that fasting is merely external. External acts stem from the desires of the heart within, as Our Lord says in the Gospel. [4] So, a person's external acts are linked to his interior desires. The external act of abstaining from food and drink, therefore, clearly affects a person internally. It does not permit his desires within to reach fulfillment. Thus fasting has the ability to keep interior desires in check, which is important for improving a person's interior life.

It is true, of course, that a person should be more vigilant over his interior life than over his external actions. He must be attentive to interior motives, desires, intentions, to make sure that his fasting is affecting his interior life as it ought–and not giving rise to pride, anger, or impatience.

In fact, only by considering the interior self, and how fasting can affect it, does one see the high value of fasting. If someone looks only at the external act of eating, and does not consider the underlying internal desires of the heart, then the value of fasting cannot be seen. For, clearly, there is nothing wrong with the very act of eating. Nor do the enjoyments of food and the pleasures of eating, as such, harm a person. The joys and comforts of eating are good. Like all created goods, they testify to the goodness of God, who made them. Therefore, the enjoyment of eating and drinking manifests the goodness of God. A person ought to see God's goodness in the joys of these things, and give God thanks for them. [5] The enjoyment of food can then actually help lift the mind and heart to God. [6]

But by lifting a person's gaze to God, created goods point beyond themselves, to greater joys. Consequently, he who truly enjoys God's goodness in created things, such as food and drink, will not remain attached to them. Rather, he will go beyond them, readily giving them up, in order to enjoy the higher things, which St. Paul says we must seek. [7]

Seek What Is Better

This might lead some to ask: If the enjoyment of eating does me no harm, and can in fact manifest God's goodness, why sacrifice this joy by fasting? That is, why check my unnecessary desires for what is enjoyable? After all, there is nothing wrong with enjoying food. Why, then, if I enjoy having a snack, or eating fine foods, sacrifice these things? Again, they are not bad or sinful.

The answer is: Because it is better. Having a tasty meal prepared just to my liking is good, but it is better to sacrifice such things. Showing why it is better to fast than to neglect fasting will provide the reason why a Christian is expected to fast.

A Christian must be seeking what is better, and not merely trying to avoid what is bad. This is the only way to live a life of continual conversion, to which we are committed by baptism. The Christian must face decisions with the question: "What is the better thing for me to do?" He must not, when he has a decision to make, approach what he is inclined to do with the justification: "Well, there is nothing wrong with doing it." If that is his approach, then he is not genuinely seeking improvement in his life. Spiritual progress becomes impossible.

Ongoing conversion, to which, again, the Christian must be dedicated, involves going from good to better. This conversion is unreachable for him who in his life refuses to give up the lesser goods in order to attain greater goods. Due to fallen human nature, every person is prone to be complacent. Each of us is reluctant to change his ways. But clearly, if a person has not yet reached perfection, there are certainly greater goods for him to realize. Fasting, in many ways, is simply the choice to give up lesser goods for greater ones, to abstain from the joys of food and drink in order to attain greater joys from God. It seeks for more. If a person ever stops seeking for more, then he has stopped seeking God.

Why is it better to fast than not to fast? Again, we said that the enjoyment of food and drink is good. Enjoying food is not the problem. Fasting does not tell a person not to enjoy eating–I think this is impossible–as much as it says not to seek the enjoyment of eating. A person may take the joys of food as they come, and be grateful for them: but he should not pursue such joys.

True, there are legitimate occasions, such as when entertaining guests, where especially enjoyable foods are procured. But this is done for the sake of hospitality and for lifting up the heart and mind to God in thanksgiving. The joys of food and drink are not sought, consequently, for their own sake but for God's glory. Thus, the person is not really seeking the joys of eating and drinking, as such: he uses them only to pass beyond them to God. Hence, he who uses the joys of eating and drinking rightly will readily give them up. Because fasting is better than not fasting, he will deny himself these joys regularly. "Looking to the reward," [8] moreover, he will not often make the excuse that hospitality, or the "need" to celebrate, requires that he allow himself enjoyable foods. In truth, it is more often the case that self-denial and restraint are called for. [9]

Obstacles To Grace

So, it is not wrong, in itself, to seek tasty, enjoyable food: but still a person should not do so. For when a person seeks the enjoyment of eating, his action is tainted with inclinations to sloth, complacency, and self-love. [10] That is, his motives are mixed. For when he seeks the joys of food, selfish inclinations are at work in his heart along with whatever good motives there might be. Now, if a person only looks at the external act of eating or the objective value of enjoying food, he will not see this. But, if he honestly looks into the heart, he will see that sloth, complacency, and self-love are present in the desire for the joys of eating. Having such mixed motives is simply part of our imperfect condition in this world.

These selfish inclinations in a person's heart, which are present when he seeks the enjoyment of eating, are the sort of things that hinder a person's growth in holiness and virtue. To grow in holiness and virtue every person needs God's help–we know that a person cannot do it on his own. As Christ says, "Apart from me you can do nothing." [11] Hence, the help of God's grace is needed to grow in virtue and to live a life of continual conversion. Yet the presence of these inclinations to sloth, complacency, and self-love get in the way of a person's reception of God's grace. They are obstacles to receiving more grace.

Therefore, the Christian, who is dedicated to conversion, must remove these obstacles from his heart, so that he may receive more grace and become a better follower of Christ. A person should not expect God to force his grace on him without his consent. As we know, God chooses to work with a person's cooperation. And, so, he is obliged to work with God to remove these inclinations from his heart as much as possible.

This is done by fasting. For fasting, by checking a person's desires for what is not necessary, teaches him to seek what is sufficient when he eats. When he fasts, he does not seek the enjoyment of food, but is simply seeking what he needs to eat and drink. And since he is no longer pursuing the joys of food, the self-centered inclinations that accompany this pursuit are not allowed a chance to spring up in his heart. A person gives up things he enjoys because in so doing he denies inclinations such as sloth, complacency, and self-love a chance to be active in his heart.

Purifying The Heart

This is why it is better to fast. Fasting removes these obstacles so that being more receptive to God's grace, a person will grow in holiness and virtue. The self-centered inclinations that accompany pleasure-seeking are not directed towards God–therefore, they do not lead the heart to God but away from him. Their presence in the heart creates a divided heart–a heart, which does not completely look to God for its needs. As St. Augustine teaches, a divided heart is an impure heart. [12]

Purifying the heart, then, will involve denying oneself the pursuits of pleasures in things like food and drink. For thus a person protects his heart from the self-centered inclinations that are bound to coexist with these pursuits.

This provides one answer to the question, "Why must we fast?" (and, by extension, to the question, "Why should one practice self-denial?"). Since, by fasting, a person no longer seeks after the joys of food and drink, the heart is set free to focus more completely on God. By turning away from his concerns for the pleasures of eating, he can turn more wholeheartedly to God. And this, we know is what continual conversion is all about.

[image error]

[image error]

By fasting, then, a person turns to God more intently. This is reflected in God's words spoken through the Prophet Joel: "Return to me with all your heart, with fasting, with weeping, and with mourning." [13] Naturally, a person is reluctant to give up through fasting things he enjoys–but by doing so he turns his attention to God and waits for him. He places his trust in him that he will give him the joy he needs–joys "greater than when grain and wine abound." [14] But he has to trust and be willing to persevere through the dry times that will accompany fasting. If he puts his hope in God, however, the Scriptures assure him that he will not be disappointed. [15]

For the sake of his ongoing conversion, then, the Christian must fast. But we might add another, better reason for fasting. Not only does fasting benefit a person's own individual spiritual progress, it also benefits his neighbor.

It is commonly pointed out that fasting can help others by allowing those who fast to increase their almsgiving with the money saved from eating less. But the benefit referred to here is of a different sort. It is due to our being connected with each other through prayer, so that a person's offering of prayer can help others. Now, prayers for others are more effective the more united the person praying is to Christ, since Christ is the source of the benefits gained through prayer. So the more converted a person becomes to the Lord, the more effective his prayers for others: "The prayer of a righteous man has great power in its effects." [16] And since fasting aids a person's continual conversion, it strengthens his prayers so that they benefit others more. In this way, he can help his neighbor through fasting.

Moreover, this service to his neighbor through fasting is an imitation of Christ. He offered himself on the Cross for others. A person too, in union with Christ, offers himself through the sacrifice of fasting. In fasting, he has the opportunity to join Christ in offering himself for the sake of others. Thus, even if a person's heart were pure and always free from selfish inclinations–as was Christ's–he should still fast–as did Christ. Through Christ he has the chance of helping others through voluntary acts of self-denial. Christian love is, indeed, eager for such chances to serve others.

So, in a very real way that is clearly visible to the eyes of faith, the Christian must fast out of love of neighbor. He is commanded by Jesus to live in his love. [17] This love is the love that compels a person "to lay down his life for his friends." [18] That is, it is the love that compels him to sacrifice his own preferences and desires on behalf of others. And this is what each person is invited to do through fasting– to give up things he enjoys for the benefit of others. And, as we are told, "there is no greater love than this." [19]

There are good reasons then, why a person must practice fasting and develop disciplined eating habits. Fasting and, by extension, self-denial are important for a person's continual conversion as well as for others who need our prayers. So, the Christian should regularly ask himself, "What do I really need? What can I do without?" and consider the advantages of denying himself even things that are not necessarily bad.

A better understanding of the virtue of denying oneself would undoubtedly benefit our society, where one is taught only how to say, "yes" to what one wants and desires. The practice of self-denial provides a humble yet profound way of giving oneself to God and others out of love, thus breaking the tendency to self-absorption. For, as we have said, self-denial is necessary for helping bring about ongoing conversion, which is sought out of love of God: and one restrains oneself and sacrifices one's desires out of love of neighbor. Love, then–real liberating, sacrificial love–is behind voluntary self-denial.

This article was originally published in the February 2000 issue of Homiletic & Pastoral Review.

ENDNOTES:

[1] Luke 16:10.

[2] John Cassian Institutes 5.23.

[3] Augustine Rule 3.1.

[4] Luke 6:45.

[5] 1 Tim. 4:3-5.

[6] The theme of the mind ascending from created goods to God, the Ultimate Good, is common among spiritual writers. The spiritual master, Saint John of the Cross, refers to it in The Ascent of Mount Carmel (trans. Kieran Kavanaugh, O.C.D., and Otilio Rodrigues, O.C.D., in The Collected Works of St. John of the Cross [Washington, D.C.: Institute of Carmelite Studies Publication, 1979]) 3.24.3-7,3.26.5-7. For a more recent discussion on the subject, see Dietrich von Hildebrand Transformation in Christ (Garden City, N.Y.: Image Books, 1963) 192-193.

[7] Col. 3:1-2.

[8] Heb. 11:26.

[9] For further insights into this subject, see Saint John of the Cross, op. cit.

[10] See Dietrich von Hildebrand In Defense of Purity (New York: Sheed and Ward Inc., 1935) 150-156.

[11] John 15:5.

[12] Augustine The Lord's Sermon on the Mount 2.11.

[13] Joel 2:12.

[14] Ps 4:8.

[15] Rom. 5:5: Ps 22:5.

[16] Jas. 5:16.

[17] John 15:9.

[18] John 15:13.

[19] Ibid.

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles:

• The Premises of Gospel Poverty | Fr. Thomas Dubay, S.M.

• Lent and "Our Father": The Path of Prayer | Carl E. Olson

• Thirsting and Quenching | Fr. Thomas Dubay, S.M.

• Seeking Deep Conversion | From Deep Conversion, Deep Prayer | Fr. Thomas Dubay, S.M.

• "Lord, teach us to pray" | From Earthen Vessels | Gabriel Bunge, O.S.B.

• The Religion of Jesus | From Christ, The Ideal of the Priest | Blessed Columba Marmion

• Blessed Columba Marmion: A Deadly Serious Spiritual Writer | Christopher Zehnder

• Seeing Jesus in the Gospel of John | Excerpts from On The Way to Jesus Christ | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• Encountering Christ in the Gospel | Excerpt from My Jesus | Christoph Cardinal Schönborn

• The Liturgy Lived: The Divinization of Man | Jean Corbon, OP

• Understanding The Hierarchy of Truths | Douglas Bushman, STL

• The Eucharist: Source and Summit of Christian Spirituality | Mark Brumley

Brother Austin G. Murphy, O.S.B., is a member of St. Procopius Abbey in Lisle, Ill. He was born in Huntington, L.I., and grew up in Suffern, N.Y. In December of 1995 he received his B.A. in Economics from the University of Chicago. While in formation and preparation to take solemn vows at St. Procopius Abbey, he teaches high school mathematics at the abbey’s high school, Benet Academy.

February 17, 2015

Benedict XVI, Cardinal Jean Danielou, and a Modern World in Crisis

Retired Pope Benedict XVI greets a cardinal before a consistory at which Pope Francis created 20 new cardinals in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican Feb. 14. (CNS photo/Paul Haring). Right: Jean Danielou, SJ (1905-74) in an undated photograph.

Benedict XVI, Cardinal Jean Danielou, and a Modern World in Crisis

How the retired pontiff and his "scandalous" hero addressed false interpretations of Vatican II and "a false conception of freedom"

Rome, Italy, Feb 15, 2015 / 05:05 pm (CNA/EWTN News).- Theological giants Benedict XVI and one of his heroes – the controversial Cardinal Jean Danielou – have been hailed for illuminating through their respective works the ever-relevant answer to a modern world in crisis: Jesus Christ.

“If you want to be modern, you have to look at Jesus,” Rome-based theology professor Father Giulio Masparo told CNA Feb. 13.

And through the writings of the late French cardinal in particular, he noted, the Christian claim in today's world is infinitely superior “than what you can find by thinking that everything is relative.”

Fr. Masparo, a professor in Dogmatic Theology at the Pontifical University of Santa Croce in Rome, helped to organize a Feb. 12-13 conference titled: “Study days: Danielou-Ratzinger before the Mystery of History.”

Held at the University of Santa Croce, the conference explored the great continuity between Cardinal Danielou and Benedict XVI, who are both known for placing a historical frame around their theological writings.

Originally from Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, Cardinal Danielou was a Jesuit, and is considered one of the greatest theologians of the 20th century. He is known for his clarity in explaining profound concepts in a comprehensible way for the unlearned reader.

Danielou was highly criticized following the Second Vatican Council, a false interpretation of which he faulted for the crisis in religious life and the increase in secularization which ensued.

In a controversial interview with Vatican Radio in 1972, the cardinal stressed that “Vatican II declared that human values must be taken seriously. It never said that we should enter into a secularized world in the sense that the religious dimension would no longer be present in society.”

“It is in the name of a false secularization that men and women are renouncing their habits, abandoning their works in order to take their places in secular institutions, substituting social and political activities for the worship of God,” he said.

Cardinal Danielou also faulted “a false conception of freedom” that devalued religious constitutions and “an erroneous conception of the changing of man and the Church” for many of the crisis that unfolded after the Vatican council.

However, despite the criticism directed at the French cardinal, then-Bishop Josef Ratzinger was an avid supporter of Danielou, and placed great value on his stance and writings.

February 16, 2015

Preaching, Music, and Acoustics

Preaching, Music, and Acoustics | Deacon W. Patrick Cunningham | Homiletic & Pastoral Review

The work of the New Evangelization is identical to the work of evangelization in every age: to communicate to those who are unaware of the saving work of the Son of God those things that will bring them to accept the gift of faith, and come to new life through the sacraments entrusted to the Church. What is “new” is the environment and the means. The environment in which we operate most of the time is, at best, neutral to the work of the Church. At worst, it is actively hostile to the teachings of Christ in the Church. It is necessary, then, to use new methods and new communications media to help Jesus Christ and the Church become visible and attractive to modern humans.

Now the Catholic Church has many advantages in this mission, as she always has. These advantages are summarized in the “three Cs” which are creed, cult, and code/community. I prefer to speak of the three transcendentals that are embodied in the Church as they are in no other institution. They are Truth, Goodness, and Beauty. The fullness of Truth is preached, and always has been, in the Catholic Church. The sacraments and the doctrines of the Church have helped and continue to help many to attain to saintly Goodness. And in the sacramental forms, prayers, architecture, and music, there is Beauty that is truly a making present on earth the Beauty of the Kingdom of God.

In the 21st century, however, the Church operates at a distinct disadvantage within the culture, and some of that problem is of our own making. Relativism, as communicated through the media, universities, and political institutions, is rampant in society. Many believe that there are many truths, not just One Truth. When we preach the Truth, particularly in sexual and family morals, we are teaching things that annoy, rather than attract. The media have, since the dawn of the new millennium, made it a daily objective to find people, particularly clergy, doing evil in the Church. The sexual abuse scandal and occasional financial irregularity casts doubt on the moral integrity of the leaders of the Church. Thus the millions who find Goodness in the Church, and who daily do good for others, including their persecutors, are ignored.

Beauty, however, has a way of disarming the critic and providing an instant experience of transcendence. As Dr. William Mahrt says, “beauty persuades by itself.”1That is, as traditional philosophy teaches us, in the very perception of the Beautiful, “the intellect is delighted,” and that delight is intrinsic and immediate. By contrast, the apprehension of Truth must come from reasoning, and the apprehension of Goodness by a positive act of the will, informed by the actions of the intellect. These processes can be corrupted because of the weakness of the intellect and will, engendered by Original Sin. Our apprehension of the Beautiful is immediate, and so, is harder (but not impossible) to corrupt.

Thus, if the Catholic Church is to appeal to modern humans, we must “lead with Beauty.”

On the "Reform" of Islam

The Blue Mosque, left, and the Hagia Sophia Museum, right, are pictured at sunset in Istanbul in this Nov. 24, 2008, file photo. (CNS photo/Tolga Bozoglu, EPA)

On the "Reform" of Islam | Fr. James V. Schall, SJ | CWR

If violence, terror, beheadings, forced conversions, subjection of women, and intolerance of others are removed or “transformed” in Islam, is it still Islam?

I.

The President of Egypt, at Al Azhar University in Cairo, recently did everyone a favor by putting on the table, from inside of the Islamic world itself, the question of its public conduct and inner soul as they relate to the Muslim religion. Does its conduct, as manifest in its deeds, flow from its religious beliefs? One and a quarter billion Muslims, President al-Sisi bluntly affirmed, cannot hope to eliminate the other six and a half billion human beings. A May 14, 2014, article in the American Thinker estimated that over the centuries some 250 million people have been killed in wars caused by Islam. The religion itself thus needs, in al-Sisi’s view, a thorough “revolution” or transformation.

The issue that I bring up here, in the light of these observations, is this: “Is such a revolution possible without, in effect, eliminating the basic content of what we know as Islam?” If violence, terror, beheadings, forced conversions, bad treatment of women, and intolerance of others are removed or “transformed” in Islam, so that they are no longer parts of the religion but condemned by it, is it still Islam? Would it not be something totally unrecognizable as the same Islam faithfully loyal to its founding by Mohammed? If so, it would follow that something is radically disordered in the founding itself and its development to its present form.

No one thought that communism could fall except, perhaps, Reagan and John Paul II. Some elements of it still strive to hang on, to be sure, but its evils have generally been acknowledged as inhuman. Is there a similar hope about an unexpected turn in Islam? Could it almost miraculously morph into something else? Or, if it changes in any basic way, does it not have to change into something already known, such as Christianity? Or Hinduism? Or even modernism? Are the violent manifestations within Islam towards itself and others simply an aberration? Or, are they essential to the mission to which Islam is committed, namely, to conquer the world for Allah? The authors of Charlie Hebdo hoped that Islam would become as “harmless” as Christianity has become. But is a “harmless” Islam an irrelevant Islam?

In 2011, I called attention to the work of scholars (mostly German) in establishing a critical edition of the Qur’an. It becomes evident that the text of this famous book could not be what it is claimed to be—that is, a revelation in pure Arabic delivered directly from the mind of Allah in the seventh century through Mohammed. Moreover, it is said to be unchanged in any way, not only from its first appearance, but also from eternity.

My assumption, of course, is that the Muslim mind—or any mind—when faced with facts, can recognize a contradiction in its own origins or practices if pointed out. If the Qur’an cannot be what it said it was, how can anyone uphold it? If it is a correlation to previously existing texts, its origin is not what it said it was. The effort to eliminate the scholars who even dare to wonder about this issue is not an argument in favor of the Qur’an, but against it, a sign of unwillingness to examine the evidence. One can only suspect that the failure of any source in Islam itself to produce a critical edition of the Qur’an, combined with the efforts to impede anyone else from doing so, is an indirect proof that many in Islam know there is something strange about the original text that is not explained by the theory of direct revelation.

II.

Muslim thinkers, in the light of contradictory statements in the Qur’an, have had to devise a philosophical thesis about Allah’s nature that would, supposedly, defend the text from incoherence.

February 14, 2015

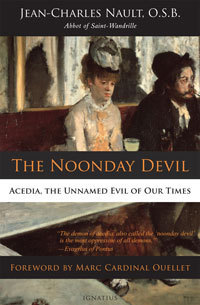

New: "The Noonday Devil: Acedia, the Unnamed Evil of Our Times"

Now available from Ignatius Press:

The Noonday Devil: Acedia, the Unnamed Evil of Our Times

by Dom Jean-Charles Nault

Foreword by Marc Cardinal Ouellet

The noonday devil is the demon of acedia, the vice also known as sloth. The word “sloth”, however, can be misleading, for acedia is not laziness; in fact it can manifest as busyness or activism. Rather, acedia is a gloomy combination of weariness, sadness, and a lack of purposefulness. It robs a person of his capacity for joy and leaves him feeling empty, or void of meaning

Abbot Nault says that acedia is the most oppressive of demons. Although its name harkens back to antiquity and the Middle Ages, and seems to have been largely forgotten, acedia is experienced by countless modern people who describe their condition as depression, melancholy, burn-out, or even mid-life crisis.

He begins his study of acedia by tracing the wisdom of the Church on the subject from the Desert Fathers to Saint Thomas Aquinas. He shows how acedia afflicts persons in all states of life— priests, religious, and married or single laymen. He details not only the symptoms and effects of acedia, but also remedies for it.

Dom Jean-Charles Nault, O.S.B., has been the abbot of the Benedictine Abbey of Saint-Wandrille (or Fontenelle Abbey) in Normandy, France, since 2009. He entered the monastery in 1988, earned a doctorate in theology from the John Paul II Pontifical Institute in Rome (Lateran University), and received from Pope Benedict XVI, then Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, the first Henri de Lubac Prize for his thesis on acedia, La Saveu de Dieu.

Praise for The Noonday Devil:

"The simple, direct style of this work makes the reader feel involved and challenged to consider anew what is essential in his existence."

- Cardinal Marc Ouellet, Prefect of the Congregation for Bishops (Rome)

"A must read for anyone who takes the spiritual life seriously. Christ's passion and death on the cross is the most perfect answer to the terrible evil that tells man his very existence is meaningless."

- Mother Dolores Hart, O.S.B., Author, The Ear of the Heart

"With clarity and penetrating insight, Abbot Nault unmasks the pernicious demon of acedia, showing how it tempts souls in every state of life and why it may well be the zeitgeist of our time. A most helpful and encouraging book on a long-overdue topic."

- Johnnette Benkovic, EWTN host; Founder, Women of Grace®

"A revelation, a modern-day treatise on an ancient and yet familiar foe. This book can transform the spiritual life of those willing to dive in and go deeper."

- Vinny Flynn, Author, 7 Secrets of the Eucharist

"Dom Nault's book shows how acedia is the unwillingness to ask the questions about the meaning of our lives. Hence those burdened by the vice busy themselves in all sorts of activities and distractions. Nault's reflections are most welcome in a world that sees so much darkness at noon-time and wonders why."

- James V. Schall, S. J., Author, Reasonable Pleasures

Christianity: "Pie in the sky" religion, or "island of mercy and security"?

Detail from "Healing of the Lepers at Capernaum" (1886-94) by James Tissot [WikiArt.org]

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Sunday, February 15, 2015 | Sixth Sunday of Ordinary Time | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Lev 13:1-2, 44-46

• Psa 32:1-2, 5, 11

• 1 Cor 10:31-11:1

• Mk 1:40-45

The sociologist Rodney Stark, in The Triumph of Christianity (HarperCollins, 2011; $27.99), confronted the notion that Christianity is a “pie in the sky” religion that attracted adherents in its first centuries by merely promising eternal life.

“What is almost always missed”, Stark writes, “is that Christianity often puts the pie on the table! It makes life better here and now.” He details how life in the ancient world was almost unremittingly filthy and unsanitary, and that disease and physical affliction “probably were dominant features of daily life.” Stark states: “In the midst of the squalor, misery, illness, and anonymity of ancient cities, Christianity provided an island of mercy and security. Foremost was the Christian duty to alleviate want and suffering. It started with Jesus.”

Some might be tempted, in reading of the miraculous healings performed by Jesus, to interpret his actions as primarily displays of power and divinity—as if the sick and possessed were props conveniently providing a way for Jesus to say, in essence, “You doubt that I am God, do you? Watch this!” But the power of Christ over sin and death is never separate from the mercy of Christ toward those who suffer from sin and the inevitability of death.

Put another way, God did not become man because he needed the praise of men. He became man so he could, in his divine humility, touch us and save us from both physical evils and spiritual destruction.

The reading from Leviticus 13 provides context for the Gospel reading in describing some of the measures required of those who had leprosy, which likely refers to a range of serious skin disorders including Hansen’s disease. Those afflicted had to present themselves to the priests, who would then diagnose the disease and, if necessary, “declare him unclean”. This was in many ways a sort of death sentence, at least relationally, because the leper had to live outside of the community, identifying himself as “Unclean, unclean!” Leviticus 14 describes the steps of ritual purification administered to those who recovered from their disease, a most happy if uncommon event.

The Law, then, could identify the disease and provided a practical means to protect the people from the disease spreading. But the Law could not cure the disease; it was able only to acknowledge when the disease had disappeared. This contrasts strikingly with Jesus, the great and holy high priest, who did not merely look upon the leper’s diseased body, but stretched out his hand, touched the unclean man, and healed him: “The leprosy left him immediately.”

Yet Jesus did not use this amazing act as a weapon against the Law, but told the man to present himself to the priests as directed in Leviticus 14. In fact, Jesus sternly warned the man to say nothing of the healing, an action described several times in Mark’s Gospel (cf. Mk 1:44; 5:43; 7:36; 8:26, 30; 9:9); he wished his identity as the true Messiah—not a military leader or political zealot—to be revealed slowly and at the proper time. Jesus knew how his miracles could be misunderstood and misused by those anxious to overthrow the Romans. But the real Messiah is revealed in humility and mercy, through acts of selfless love and life-giving sacrifice.

A paradox is then described. When the healed leper, contra Jesus’ admonition, did spread the word, it forced Jesus to live and carry out his ministry outside the town—that is, outside the camp. The holy one who had healed the leper became “unclean”, a sort of leper, having to remain in deserted places. But what happened then? The people “kept coming to him from everywhere”. The divide between what was thought clean—the sinful people in need of cleansing—and perceived as unclean—the mysterious man who touched the leper—was removed.

The limitations of the Law were revealed, but the Law was also fulfilled by the Law-giving Son of God, the only priest who can see our sins and heal both body and soul.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the February 12, 2012, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers