Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 304

July 4, 2011

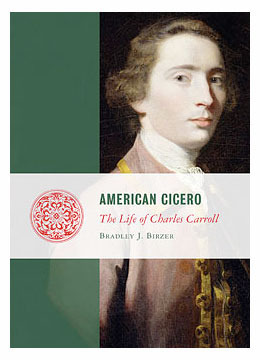

Charles Carroll, founding father and "an exemplar of Catholic and republican virtue"

Charles Carroll of Carrollton, the only son of Charles Carroll of Annapolis, was born in 1737 and died in November 1832. He was the lone Catholic to sign the Declaration of Independence and the last of the signers to die. Last year I interviewed Dr. Brad Birzer, Assistant Professor of History at Hillsdale College and author of American Cicero: The Life of Charles Carroll (ISI, 2010). Here is some of that interview:

Ignatius Insight: In what ways was Charles Carroll an "American Cicero"?

Dr. Birzer: Beginning sometime in his teenage years, Carroll fell in the love with the life, the ideas, and the writings of Cicero. From that point until his death in 1832, Carroll considered Cicero one of his closest friends and, as he put it, a constant companion in conversation. After the teachings of Christ and the Bible, he said toward the end of his life, give me the works of Cicero. Again, as Father Hanley has argued, Carroll truly was a Christian Humanist, blending the Judeo-Christian with the

Greco-Roman traditions of the West quite nicely in his person as well as in his intellectual life.

Greco-Roman traditions of the West quite nicely in his person as well as in his intellectual life.

The founders, overall, greatly respected Cicero. Not only had he served as the last real bulwark against the encroachment of tyranny and empire in ancient Rome, but he represented the best a republic had to offer, then or now. Probably Carl J. Richard, author of The Founders and the Classics and Greeks and Romans Bearing Gifts, has presented the most extensive and best work on this. Forrest McDonald, too, has done yeoman's work. Classicists Christian Kopff and Bruce Thornton have published excellent studies on this as well.

In many ways, Carroll resembled Cicero not at all. Certainly, no leader ever hunted down Carroll, as Marc Antony did to the great Roman senator. And, while Carroll could speak with force, dignity, and clarity, his oratorical skills could in no way match Cicero's.

But, like Cicero--and, indeed, inspired in large part by the example and words of Cicero--Carroll always put the needs of the res publica ahead of his own personal self interest. In fact, I couldn't find an instance in Carroll's public life where he did not always put the good of the republic ahead of his own good. He served as a model leader.

When I first sent the manuscript to ISI, I had wanted to name the book, "The Last of the Romans: The Life of Charles Carroll." The title, "Last of the Romans" was given to Carroll at his death. It's fitting. Jed Donahue, ISI's new editor, rightfully thought Carroll too obscure a figure to give such a title to his biography; an audience might justly believe the book to be about ancient history. My close friend and colleague, Dr. Mark Kalthoff, came up with the clever title "Papist Patriot." While Kalthoff's title is certainly catchy and edgy, I didn't want to have to explain to Catholic audiences why I was using a term usually associated with an insult.

In the end, American Cicero seemed fair and just, as it tied the founding to the ancient world without forgetting the medieval or the early modern worlds. As another close friend of mine, Thomas More and Shakespeare scholar, Stephen Smith, has argued in private conversation, "Cicero serves as a key to true reform and progress in the western world." And, of course, Smith is right. We can't even imagine St. Augustine, Petrarch, or Thomas More without the Ciceronian element. The same should be true of the American founding. To my mind, among the American founders, Charles Carroll best continued the Ciceronian legacy.

Ignatius Insight: In the Introduction, you describe Carroll as "an exemplar of Catholic and republican virtue." What are some examples of each?

Dr. Birzer: Just as figures (some mythical, some historical, most a combination of both) such as Cincinatus and Cicero served as exemplars for the American founders, so Carroll should serve as an exemplar for us. Carroll devoted his considerable resources and gifts to the common good.

We live, however, in an age of cynicism and scandal. Such men as Washington or Carroll seem like cardboard figures to us, mostly because we can no longer imagine what real service and sacrifice means, especially to something so "old fashioned" as the republic. All we have to do is give a sidelong glance toward Washington or Wall Street to see where our society as "progressed": deals, corruption, and the radical pursuit of self-interest infect, inundate, and adulterate almost every aspect of our institutions and so-called leadership. A figure who stands for right seems the fool, the buffoon, or the flighty romantic, merely positioned to be stepped upon or used.

And, of course, this isn't true for everyone in what remains of our constitutional republic. Just this past weekend, I learned that 13 of our roughly 280 graduates of the Hillsdale Class of 2010 have joined the Marines. At least one graduate is heading off to a Catholic monastery; another is off to Orthodox seminary to become a priest. So, a few good men and women remain.

Sadly, though, these Hillsdale students serve as exceptions in a larger culture that puts security and material comfort above eternal certainties.

Throughout his public career, Carroll defended the soul and nature of the republic. Like many of the founders, he believed that no people could enjoy the blessings of liberty without the virtue necessary to maintain it. If a man cannot order himself, how can we expect him to order his community?

For Carroll, republican virtue would have flowed neatly into a Catholic understanding of the world. Virtue--our English equivalent of "virtu" or "manly power"--animates a person as well as a society. During the revolution, Carroll used much of his own wealth to maintain armies as well as governments. Never did he expect to be paid back for any of this. As he saw it, God placed him in that time and that place. His material wealth, a blessing, could only be sanctified by using it for God's greater glory. In the providence of history, Carroll believed, the American revolution served not only to give an example of religious liberty to the world, but also a representation and manifestation of God's desire for man to reform, to purify, and to bring society back to first principles.

July 3, 2011

Chesterton Defines and Defends Patriotism

The opening section of G. K. Chesterton's essay, "The Patriotic Idea", first published in 1904, and included in G. K. Chesterton: Collected Works, Volume XX: Christendom in Dublin, Irish Impressions, The New Jerusalem, A Short History of England (also available in softcover), which was edited by Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.:

I

The scepticism of the last two centuries has attacked patriotism as it has attacked all the other theoretic passions of mankind, and in the case of patriotism the attack has been interesting and respectable because it has come from a set of modern writers who are not mere sceptics, but who really have an organic belief in philosophy and politics. Tolstoy, perhaps the greatest of living Europeans, has succeeded in founding a school which, whatever its faults (and they are neither few nor small), has all the characteristics of a great religion. Like a great religion, it is positive, it is public, above all, it is paradoxical. The Tolstoyan enjoys asserting the hardest parts of his belief with that dark and magnificent joy which has been unknown in the world for nearly four hundred years. He enjoys saying, "No man should strike a blow even to defend his country," in the same way that Tertullian enjoyed saying,"Credo quia impossible."

This important and growing sect, together with many modern intellectuals of various schools, directly impugn the idea of patriotism as interfering with the larger sentiment of the love of humanity. To them the particular is always the enemy of the general. To them every nation is the rival of mankind. To them, in not a few instances, every man is the rival of mankind. And they bear a dim and not wholly agreeable resemblance to a certain kind of people who go about saying that nobody should go to church, since God is omnipresent, and not to be found in churches.

Suppose that two men, lost upon some gray waste in rain and darkness, were to come upon the light of a porch and take shelter in some strange house, where the household entertained them pleasantly. It might be that some feast or entertainment was going forward; that private theatricals were in preparation, or progressive whist in progress. One of these travellers might lend a hand instinctively and heartily, might play his cards at whist in a fighting spirit, might black his face in theatricals and make the children laugh. And this he would do because he felt kindly towards the whole company. But the other man would say: "I love this company so much that I dislike its being divided into factions by progressive whist; I love so much the human face divine that I do not wish to see it obscured with soot or grease-paint; I will not take a partner for the lancers, for that would involve selecting one woman for special privilege, and I love you all alike." The first man would undoubtedly amuse the whole company more. And would he not love the whole company more?

Every one of us has, indeed, been lost in a gray waste of eternity, and strayed to the portal of this earth, over which the lamp is the sun. We find inside the company of humanity engaged in certain ancient festivals and forms, certain competitions and distinctions. And, as in the other case, two kinds of love can be offered to that society. The prig will profess to join in their unity; the good comrade will join in their divisions.

If the stray guests see something utterly immoral in the distinctions, something utterly wicked in the ritual, doubtless they must protest; but they should never protest because the distinctions are distinctions, and therefore in one sense exclusive, or because the ritual is ritual, and therefore in one sense irrational. If the stranger in the house has a moral objection, for instance, to playing for money, he ought to decline, though he ought not to enjoy declining. But he must not ask, "Why am I arbitrarily made a partner with So-and-so?" He must not say, "What rational difference is there between spades and diamonds?" If he really loves his kind, he will, as far as he can, and in the great mass of things, play the parts given him. He will preserve this gay and impetuous conservatism; he will throw himself into the competitive sports of nationality; he will walk with relish in the ancient theatricals of religion.

Because the modern intellectuals who disapprove of patriotism do not do this, a strange coldness and unreality hangs about their love for men. If you ask them whether they love humanity, they will say, doubtless sincerely, that they do. But if you ask them, touching any of the classes that go to make up humanity, you will find that they hate them all. They hate kings, they hate priests, they hate soldiers, they hate sailors. They distrust men of science, they denounce the middle classes, they despair of working men, but they adore humanity. Only they always speak of humanity as if it were a curious foreign nation. They are dividing themselves more and more from men to exalt the strange race of mankind. They are ceasing to be human in the effort to be humane.

The truth is, of course, that real universality is to be reached rather by convincing ourselves that we are in the best possible relation with our immediate surroundings. The man who loves his own children is much more universal, is much more fully in the general order, than the man who dandles the infant hippopotamus or puts the young crocodile in a perambulator. For in loving his own children he is doing something which is (if I may use the phrase) far more essentially hippopotamic than dandling hippopotami; he is doing as they do. It is the same with patriotism. A man who loves humanity and ignores patriotism is ignoring humanity. The man who loves his country may not happen to pay extravagant verbal compliments to humanity, but he is paying to it the greatest of compliments - imitation.

The fundamental spiritual advantage of patriotism and such sentiments is this: that by means of it all things are loved adequately, because all things are loved individually. Cosmopolitanism gives us one country, and it is good; nationalism gives us a hundred countries, and every one of them is the best. Cosmopolitanism offers a positive, patriotism a chorus of superlatives. Patriotism begins the praise of the world at the nearest thing, instead of beginning it at the most distant, and thus it insures what is, perhaps, the most essential of all earthly considerations, that nothing upon earth shall go without its due appreciation. Wherever there is a strangely-shaped mountain upon some lonely island, wherever there is a nameless kind of fruit growing in some obscure forest, patriotism insures that this shall not go into darkness without being remembered in a song.

There is, moreover, another broad distinction, which inclines us to side with those who support the abstract idea of patriotism against those who oppose it. There are two methods by which intelligent men may approach the problem of that temperance which is the object of morality in all matters—in wine, in war, in sex, in patriotism; that temperance which desires, if possible, to have wine without drunkenness, war without massacre, love without profligacy, and patriotism without Sir Alfred Harmsworth. One method, advocated by many earnest people from the beginning of history, is what may roughly be called the teetotal method; that is, that it is better, because of their obvious danger, to do without these great and historic passions altogether. The upholders of the other method (of whom I am one) maintain, on the contrary, that the only ultimate and victorious method of getting rid of the danger is thoroughly to understand and experience the passions. We maintain that with every one of the great emotions of life there goes a certain terror, which, when taken with imaginative reality, is the strongest possible opponent of excess; we maintain, that is to say, that the way to be afraid of war is to know something about war; that the way to be afraid of love is to know something about it; that the way to avoid excess in wine is to feel it as a perilous benefit, and that patriotism goes along with these. The other party maintains that the best guarantee of temperance is to wear a blue ribbon; we maintain that the best guarantee is to be born in a wine-growing country. They maintain that the best guarantee of purity is to take a celibate vow; we maintain that the best guarantee of purity is to fall in love. They maintain that the best guarantee of avoiding a reckless pugnacity is to forswear fighting; we maintain that the best guarantee is to have once experienced it. They maintain that we should care for our country too little to resent trifling impertinences; we maintain that we should care too much about our country to do so. It is like the Mohammedan and Christian sentiment of temperance. Mohammedanism makes wine a poison; Christianity makes it a sacrament.

Many humane moderns have a horror of nationality as the mother of wars. So in a sense it is, just as love and religion are. Men will always fight about the things they care for, and in many cases quite rightly. But there is another thing which should not be altogether forgotten, and that is this: that in so far as men increase in intelligence they must see that a quite primary and mystical affection is a foolish thing to put into violent competition with another thing of the same kind. Men may fight about a rational preference, because there victory may prove something. But an irrational preference is far too fine a thing to fight about, because there victory proves nothing.

When men first become conscious of splendid and disturbing emotions, it is their natural instinct, their first and most natural and most reasonable instinct, to kill people. Thus, for instance, the sentiment of romantic love went through the same historical evolution as the sentiment of patriotism. When a medieval knight or troubadour realized that there was an intensity in a pure and monogamous sentiment which was quite beyond anything in merely animal appetites, he immediately took a long spear and rushed round the neighbourhood offering to kill anybody who denied that he had fallen in love with precisely the right person. I do not think that it can be reasonably maintained that romantic love has decayed in the centuries succeeding this; what has happened has been that people have perceived not that love is too insignificant to fight about, but that it is too important to fight about. Men have perceived, that is to say, that in these matters of the affections all combat is ineffective, since no combatant would ever accept its issue. Each of us thinks his own country is the best in the world, just as each of us might think his own mother the best in the world. But when we think this we do not proceed, or in the least desire to proceed, to the bellicose test. We do not set our mothers to fight each other in an ampitheatre, and for the excellent reason that if one mother overcame the other mother, it would not make the least difference to anybody. That is the only serious objection to the institution of the duel. That the duel kills men seems to me a comparatively trifling matter; football and fox-hunting and the London hospitals very frequently do that. The only rational objection to the duel is that it invokes a most painful and sanguinary proceeding in order to settle a question, and does not settle it. It is our belief, therefore, that the right way to avoid the incidental excesses of patriotism is the same as that in the cases of sex or war—it is to know something about it. Just as, according to our view, there will always be in some degree the power of sex and the use of wine, so there will always be the possibility of such a thing as patriotic war. But just as a man who has been in love will find it difficult to write a whole frantic epic about a flirtation, so all that kind of rhetoric about the Union Jack and the Anglo-Saxon blood, which has made amusing the journalism of this country for the last six years, will be merely impossible to the man who has for one moment called up before himself what would be the real sensation of hearing that a foreign army was encamped on Box Hill. The light and loose talk about national victories impresses those who think with me merely as a mark of the lack of serious passion. The average reasonable citizen, of whatever political colour, would admit that such talk shows too much patriotism. We should say that it shows too little.

To the cosmopolitan, therefore, who professes to love humanity and hate local preference, we shall reply: "How can you love humanity and hate anything so human?" If he replies that in his eyes local preference is a positive sin, is only human in the sense that wife-beating is human, we shall reply that in that case he has a code of morality so different from ours that the very use of the word "sin" is almost useless between us. If he says that the thing is not positive sin, but is foolish and narrow, we shall reply that this is a matter of impression, and that to us it is his atmosphere which is narrow to the point of suffocation. And we shall pray for him, hoping that some day he will break out of the little stifling cell of the cosmopolitan world, and find himself in the open fields and infinite sky of England. Lastly, if he says, as he certainly will, that it is unreasonable to draw the limit at one place rather than another, and that he does not know what is a nation and what is not, we shall say: "By this sign you are conquered; your weakness lies precisely in the fact that you do not know a nation when you see it. There are many kinds of love affairs, there are many kinds of song, but all ordinary people know a love affair or a song when they see it. They know that a concubinage is not necessarily a love affair, that a work in rhyme is not necessarily a song. If you do not understand vague words, go and sit among the pedants, and let the work of the world be done by people who do." It is better occasionally to call some mountains hills, and some hills mountains, than to be in that mental state in which one thinks, because there is no fixed height for a mountain, that there are no mountains in the world.

G. K. Chesterton (1874-1936) Author Page | Ignatius Insight

• Articles By and About G. K. Chesterton

• Ignatius Press Books about G. K. Chesterton

• Books by G. K. Chesterton

July 2, 2011

Jesus Christ conquers by the humility that bears witness to the truth

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for July 3, 2011, the Fourteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Zech. 9:9-10

• Psa 145:1-2, 8-9, 10-11, 13-14

• Rom. 8:9, 11-13

• Matt 11:25-30

In Daughter Zion: Meditations on the Church's Marian Belief (Ignatius, 1983), his beautiful reflection on the Blessed Mother, Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger pointed out that the image of Mary in the New Testament "is woven entirely of Old Testament threads." He identified three major Marian "threads": the great mothers of the Old Testament, the figure of Eve, and daughter Zion. Regarding the third, he wrote that it encompasses a theology "in which, above all, the prophets announced the mystery of election and covenant, the mystery of God's love for Israel" (p 12).

Zion, or Jerusalem, was depicted by the prophets as being wedded to the one true God, Yahweh. During times of war and exile, when the city of Jerusalem was emptied and ruined, it was described as a barren woman (cf., Isa 54:1). The prophets also spoke of a future time when daughter Zion would be fully restored, established forever in covenantal love with God.

Today's reading from the prophet Zechariah includes one of those references, given in a passage about a future king who would save Jerusalem from her enemies. But unlike kings who rely upon military might and countless horses to keep and expand their kingdoms, this king of peace would be meek, riding upon a colt, not a great stallion. His kingdom would be rooted in spiritual purity and humility, not physical power and arrogance.

Cardinal Ratzinger noted that Paul, in pondering the reality of spiritual birth given by Christ, recognized that "the true son of Abraham is not the one who traces his physical origin to him, but the one who, in a new way beyond mere physical birth, has been conceived through the creative power of God's word of promise" (Daughter Zion, pp 18-19). Physical pedigree, power, and even life are not man's true source of meaning and purpose. Man's relationship to God is not based in genes, but grace. As Paul states in today's reading from his epistle to the Romans: "For if you live according to the flesh, you will die, but if by the spirit you put to death the deeds of the body, you will live."

This spiritual life, of course, is only possible through the meek King, the Son sent by the Father to take up the Cross and to offer us his yoke. In today's Gospel, Jesus utters a todah, a prayer of praise and sacrifice. It focuses on the paradox suggested by Zechariah: it is those who are humble and childlike who will know the Father, while those who consider themselves wise and well educated will not see Him. This is the will of the Father, who rewards those who humbly recognize him and their need for his mercy.

"Jesus conquers the Daughter of Zion, a figure of his Church," explains the Catechism of the Catholic Church, "neither by ruse nor by violence, but by the humility that bears witness to the truth" (CCC 559). It is only through the Son that the Father is known; it is his humility that opens the way to glory and eternal life. The Father gives witness to the Son, and the Son reveals the Father. God, in other words, cannot be understood or known apart from Jesus Christ: "No one knows the Son except the Father, and no one knows the Father except the Son and anyone to whom the Son wishes to reveal him."

Those stunning words were understood by the early Christians as a definitive statement about the preexistence and divinity of the Son, and they were quoted often at the Council of Nicaea (A.D. 315) as the bishops worked to articulate and define the relationship between the Father and the Son.

Why is Christ's yoke easy and his burden light? Is it because following Him requires no struggle or hardship? No, it is because he provides the means to carry the burden, the strength to endure, and the humility to live rightly. "Whatever is hard in what is demanded of us," Augustine wrote, "love makes easy."

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the July 6, 2008, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

Related on Ignatius Insight:

• "Who Do You Say I Am?" | Peter Kreeft on the Divinity of Jesus Christ

• "Hail, Full of Grace": Mary, the Mother of Believers | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger | An excerpt from Mary: The Church at the Source

• The Religion of Jesus | Blessed Columba Marmion | From Christ, The Ideal of the Priest

• Would Jesus Be in the Church Today? | Christoph Cardinal Schönborn | From Who Needs God? Barbara Stöckl in Conversation with Christoph Cardinal Schonborn

July 1, 2011

"The veneration of our Lord's Heart...."

... insofar as it honors Christ as the source and substance of our redemption, is no ordinary devotion. It is truly latreutical--a devotion which is rendered to God alone. For the Heart of Christ occupies a central position, as the focal point through which everything passes to the ultimate center in the Father--per Christum ad Patrem. It is a devotion of tremendous theological richness, containing a complete synthesis of faith, or, as Pius XI put it "summa totius religionis." The devotion is at once theocentric and anthropocentric, Trinitarian and Christocentric; it emphasizes love of God and calls eloquently to the fraternal apostolate. It may also lead to that sound eucharistic piety so greatly desired by the Second Vatican Council. This is especially true since the Eucharist, as Pope Paul VI observed, is the "outstanding gift" of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

I firmly believe that the spirituality fostered by this devotion can best meet the spiritual needs of our age. It is a practical form of spirituality which emphasizes famlliaritas cum Christo and therefore is marvelously suited to aid priest, religious and laity alike in their journey of growth in holiness. If practiced in the family, devotion to the Heart of Jesus may greatly help to counter those pagan elements of culture which all too often work their way into the sanctuary of the home.

The devotion should be made available to all. Unfortunately, the widespread ignorance throughout the Church of the devotion's rich theological foundations has greatly hindered its full appreciation and practice. It is only by returning to these sources as found in Sacred Scripture, tradition and the teaching of the Church's magisterium that we can hope to renew the devotion and thereby allow it to play a central role in the larger effort to renew the Church.

Our Lord, in his apparition to St. Margaret Mary Alacoque, communicated to her that the revelation of his Heart was "a final effort" to enkindle the fire of love in a world in which "charity had grown cold." Such is the age in which we live. William Butler Yeats foresaw the crisis of our era in a prophetic poem written at the turn of the century:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Coldness and hatred can be melted and overcome only by the fire of love. Certainly, in an age which is characterized by an increasingly hostile secularization, a spirituality which centers on love and aims at setting the world on fire is precisely what is needed to instaurare omnia in Christo.

That is from the Introduction to Heart of the Redeemer, by Timothy T. O'Donnell, S.T.D. Read the entire piece:

"Gay marriage ... represents a demand for the institutionalisation of new moral and cultural values"

Frank Furedi, writing for Spiked Online, offers this solid and rather chilling analysis of the passage of "same-sex marriage" legislation in New York State:

From a sociological perspective, the rise of the campaign for gay marriage provides a fascinating insight into the dynamics of the cultural conflicts that prevail in Western society. Indeed, over the past decade the issue of gay marriage has been transformed into a cultural weapon, which explicitly challenges prevailing norms through condemning those who oppose it. This is not so much a call for legal change as a cause, a crusade – and one which endows its supporters with moral superiority while demoting its opponents with the status of moral inferiority.

The campaign for the legalisation of gay marriage does not simply represent a claim for a right; it also represents a demand for the institutionalisation of new moral and cultural values. This attitude was clearly expressed last weekend by Trevor Phillips, chairman of the UK Equality and Human Rights Commission. He argued that Christians, particularly evangelical ones, are more troublesome than Muslims in their attitudes towards mainstream views. In particular he warned that 'an old-time religion incompatible with modern society' was driving Christians to clash with mainstream views, especially on gay issues. Incidentally, by 'mainstream' he of course means views which he endorses.

Phillips' choice of words implies that opponents of gay marriage are likely to be motivated by 'old-time religion', which is by definition 'incompatible with modern society'. From this standpoint, criticising or questioning the moral status of gay marriage is a violation of the cultural standards of 'modern society'. What we have here is the casual affirmation of a double standard: tolerance towards supporters of gay marriage, and intolerance towards opponents of gay marriage.

And so soft totalitarianism slowly hardens into overt discrimination, even oppression:

In the US, questioning the status of gay marriage is often depicted, not simply as an expression of disagreement, but as a direct form of discrimination. The mere expression of opposition towards a particular ritual, in this case gay marriage, is recast as more than a verbal statement – it is itself an act of discrimination, if not outright oppression.

So American journalist Hadley Freeman recently argued in the UK Guardian that gay marriage is not a suitable subject for debate. 'There are some subjects that should be discussed in shades of grey, with acknowledgment of subtleties and cultural differences', she wrote. But 'same-sex marriage is not one of those'. Why? Because 'there is a right answer', she hectored, in a censorious tone. The phrase 'there is a right answer' is really a demand for the silencing of discussion. And just in case you missed the point, Freeman concluded that opposition to her favourite cause should be seen for what it was: 'as shocking as racism, as unforgivable as anti-Semitism'.

It is worth noting that the rise of support for gay marriage, the emergence of this elite crusade against sexual heresy, coincides with the cultural devaluation of heterosexual marriage. Today, heterosexual marriage is frequently depicted as a site for domestic violence and child abuse. A review of academic literature on the subject would indicate a preoccupation with the damaging consequences of heterosexual marriage. Terms such as the 'dark side of the family' invoke a sense of dread about an institution where dominating men allegedly brutalise their partners and their children.

Do read the entire piece, "The unholy marriage of snobbery and snideyness" (June 27, 2011).

"Dangerous Directions": An Interview with Archbishop Joseph Kurtz, VP of the USCCB

Dangerous Directions | by Jim Graves | Catholic World Report | July 2011

Archbishop Joseph Kurtz, vice president of the USCCB, on opposition to same-sex marriage and other issues.

Archbishop Joseph Kurtz, 64, was born in Mahanoy City, Pennsylvania. He was the youngest of five children; his father was a coal miner. His three older sisters had married and moved out of the house when he was still young; hence, his closest sibling companion in his youth was his brother, George, who had Down syndrome.

As a young man, Kurtz first thought about becoming a priest after praying one day in a chapel. He was also inspired around this time by a book his sister gave him on St. Dominic and the Rosary, which is still in his possession today. The book described Dominic as an "athlete for Christ." This life appealed to him more than devoting himself to a career, so he decided to enter the seminary.

Kurtz was ordained a priest for the Diocese of Allentown, Pennsylvania in 1972. In 1999, he was named bishop of Knoxville, Tennessee, and he became archbishop of Louisville, Kentucky in 2007. In addition to his work on the diocesan level, Archbishop Kurtz serves as chairman of the Committee on Marriage and Family Life of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB). Last fall, he was elected vice president of the USCCB. Archbishop Kurtz recently spoke with CWR.

What do you believe is the proper role for the USCCB?

Archbishop Kurtz: Pope John Paul's 1998 apostolic letter Apostolos Suos tells us that episcopal conferences have a three-fold role. First, they promote unity among the bishops with the Holy Father. This role is important, and underestimated.

At each meeting, for example, the bishops make a Holy Hour and have confessions. To me, that is one of the most important things we do. It fosters unity. It is based on the call to holiness that each of us is called to embrace, especially the bishops in our leadership role. We must support each other in our mission to follow Christ on a path of holiness.

Second, episcopal conferences help diocesan bishops in their pastoral care of the local church. In my work over the past six years on the Initiative on Marriage, for example, much of what I've tried to do is to provide material to the local church that can be used in catechetical programs and our Catholic schools.

Third, and most familiar to people, episcopal conferences provide a vehicle for addressing the vital issues of our day. These include respect for human life—advocating for the common good in legislation and regulation to protect the human person from conception to natural death.

You've personally been a leader in opposition to same-sex marriage.

Archbishop Kurtz: Bishops, the Church, and society in general need to understand the public nature of marriage. Aspects of marriage are personal and private, but it is also public, because it affects society as a whole.

Many people assume that marriage is a right that the state can simply create. That is a dangerous direction in which to go. The majority of voters cannot create whatever rights they want. Marriage is a gift given to us by God and defined by him. We, as Catholics, must not be afraid to say so publicly.

We need to be forthright in speaking about the importance of defending and protecting the gift of marriage within our Church and society. We need to be able to speak forthrightly to our people on the importance of marriage, and make it clear that our respect for the individual should not be at the expense of marriage itself.

"Dangerous Directions": An Interview withArchbishop Joseph Kurtz, VP of the USCCB

Dangerous Directions | by Jim Graves | Catholic World Report | July 2011

Archbishop Joseph Kurtz, vice president of the USCCB, on opposition to same-sex marriage and other issues.

Archbishop Joseph Kurtz, 64, was born in Mahanoy City, Pennsylvania. He was the youngest of five children; his father was a coal miner. His three older sisters had married and moved out of the house when he was still young; hence, his closest sibling companion in his youth was his brother, George, who had Down syndrome.

As a young man, Kurtz first thought about becoming a priest after praying one day in a chapel. He was also inspired around this time by a book his sister gave him on St. Dominic and the Rosary, which is still in his possession today. The book described Dominic as an "athlete for Christ." This life appealed to him more than devoting himself to a career, so he decided to enter the seminary.

Kurtz was ordained a priest for the Diocese of Allentown, Pennsylvania in 1972. In 1999, he was named bishop of Knoxville, Tennessee, and he became archbishop of Louisville, Kentucky in 2007. In addition to his work on the diocesan level, Archbishop Kurtz serves as chairman of the Committee on Marriage and Family Life of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB). Last fall, he was elected vice president of the USCCB. Archbishop Kurtz recently spoke with CWR.

What do you believe is the proper role for the USCCB?

Archbishop Kurtz: Pope John Paul's 1998 apostolic letter Apostolos Suos tells us that episcopal conferences have a three-fold role. First, they promote unity among the bishops with the Holy Father. This role is important, and underestimated.

At each meeting, for example, the bishops make a Holy Hour and have confessions. To me, that is one of the most important things we do. It fosters unity. It is based on the call to holiness that each of us is called to embrace, especially the bishops in our leadership role. We must support each other in our mission to follow Christ on a path of holiness.

Second, episcopal conferences help diocesan bishops in their pastoral care of the local church. In my work over the past six years on the Initiative on Marriage, for example, much of what I've tried to do is to provide material to the local church that can be used in catechetical programs and our Catholic schools.

Third, and most familiar to people, episcopal conferences provide a vehicle for addressing the vital issues of our day. These include respect for human life—advocating for the common good in legislation and regulation to protect the human person from conception to natural death.

You've personally been a leader in opposition to same-sex marriage.

Archbishop Kurtz: Bishops, the Church, and society in general need to understand the public nature of marriage. Aspects of marriage are personal and private, but it is also public, because it affects society as a whole.

Many people assume that marriage is a right that the state can simply create. That is a dangerous direction in which to go. The majority of voters cannot create whatever rights they want. Marriage is a gift given to us by God and defined by him. We, as Catholics, must not be afraid to say so publicly.

We need to be forthright in speaking about the importance of defending and protecting the gift of marriage within our Church and society. We need to be able to speak forthrightly to our people on the importance of marriage, and make it clear that our respect for the individual should not be at the expense of marriage itself.

"Flawed arguments against applying Canon 915 in the Cuomo case persist,..."

... perhaps because sound arguments against applying the canon apparently don't. Jesuit Fr. William J. O'Malley's essay in America (20-27 June 2011) is just the latest example.

Before addressing O'Malley's claims, though, I pause to wonder why he bothered to respond to this lawyer's arguments about law in the first place? After all, O'Malley believes that laws are chiefly necessary "for people unable—or unwilling—to think." The vacuity of that claim I address below; the condescension that O'Malley shows toward those who consider legal questions important, I will ignore.

O'Malley opines that "the first sign of a dying society is a new edition of the rules." Good grief, how fatuous can a claim about jurisprudence be and yet be found worthy of printing in America magazine?

The specific rule that O'Malley dismisses is Canon 915, part of the Johanno-Pauline Code of Canon Law. Now, if O'Malley's Maxim is right and "the first sign of a dying society is a new edition of the rules", then, must we not conclude that the promulgation of the new edition of the Code in 1983 signaled the onset of the Catholic Church's death throes some 28 years ago? Apparently, that dotty old Church is taking her sweet time a-dying.

But wait, if O'Malley's Maxim is right, should not the promulgation of the Pio-Benedictine Code have been the first sign that the Catholic Church was dying in 1917, nearly one hundred years ago? Which first sign is first?

Why stop there?

Read it all on the "In the Light of the Law" blog. Yep, Dr. Ed Peters is on a roll. His posts on the Cuomo case and related matter have been, I must say, both instructive and entertaining. Just like his canon law classes.

Also see:

• "The Cuomo-Communion Controversy" by Edward N. Peters (Catholic World Report, May 2011)

Fr. Robert Barron on the "Pledge of Allegiance" controversy; meaning of Sabbath

Many excellent points made by the director of the Word on Fire apostolate:

And then there is this recent story, from the very town I've lived in for many years now:

An Oregon town's City Council voted down a proposal to say the Pledge of Allegiance before every council meeting, but later passed a compromise that seemed to make no one happy.

The approved measure allows the pledge to be recited at just four Eugene City Council meetings a year, those closest to the Fourth of July, Veterans Day, Memorial Day and Flag Day.

It was supposed to be simple, but Councilman Mike Clark soon found out when you're dealing with God and country, nothing in Eugene is easy.

Clark says all he wanted to do was unite the council and show his more conservative constituents that in this city where diversity is celebrated, their more traditional values also are important.

"It's a little ironic to see those who have championed the idea of tolerance be less tolerant on this question," Clark said. Mayor Kitty Piercy called the Pledge of Allegiance divisive. "If there's one thing the flag stands for," Piercy says, "it's that people don't have to be compelled to say the Pledge of Allegiance or anything else."

Ah, I am [sarcasm alert!] soooooo proud of the mayor! Standing up the puritanical, close-minded right-wingers who want to force her to say the Pledge of Allegiance at city council meetings in the United States! Oddly enough, Piercy is a huge supporter of public schools, which compel children to say and do things every school day, including learning about how wonderful it is to be "queer" and "trans-gendered". Piercy is also big on taking "non-divisive" stances for abortion—she has worked in the past for both Planned Barrenhood and NARAL—medical pot, "same-sex marriage", public restrooms for transgendered folks, and so forth (pick an ultra-leftist stance; she holds it). So this really has nothing to do with being divisive at all; that's just a typical leftist smokescreen.

What, exactly, is "divisive" about saying the Pledge of Allegiance? Is it too patriotic? Too idealistic? Too religious? The Fox News articles claims, rather unconvincingly, that it has little to do with religious issues (that is, saying "under God"):

In Eugene, the opposition was less about religion than anti-establishment.

Resident Anita Sullivan summed up a common viewpoint: "So you say I pledge allegiance and right there I don't care for that language," Sullivan says. "It sort of means loyalty to your country; well, I feel loyalty to the entire world."

Brilliant, Anita, brilliant. Recite the following: "I pledge allegiance to the firmament of the entire world, and to the global village for which it stands, one planet in outer space, very divided, with liberty for a few and justice for a few others." Take it to the streets, sister, starting in Iraq and Iran, then moving on to Syria, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. Hurry along!

June 30, 2011

This Fourth of July, "Confirm thy soul in self-control" and other virtues

From an essay, "This Fourth of July: Confirm Thy Soul in Self-Control", by the prolific Dr. Paul Kengor:

I encourage you to set aside the burgers and dogs and soda and beer for a moment this Fourth of July and contemplate something decidedly different, maybe even as you gaze upward at the flash of fireworks. Here it is: Confirm thy soul in self-control.

What do I mean by that? Let me explain.

The founders of this remarkable republic often thought and wrote about the practice of virtue generally and self-control specifically, two things long lost in this modern American culture of self. Thomas Jefferson couldn't avoid a reference to one of the cardinal virtues—prudence—in our nation's founding document, the Declaration of Independence, which, incidentally, ought to be a must-read for every American every Fourth of July (it's only 1,800 words). Our first president and ultimate Founding Father, George Washington, knew the necessity of governing one's self before a nation's people were capable of self-governance. As Washington stated in his classic Farewell Address, "'Tis substantially true, that virtue or morality is a necessary spring of popular government."

A forgotten philosopher who had an important influence on the American Founders was the Frenchman, Charles Montesquieu, whose work included the seminal book, The Spirit of the Laws (1748). Montesquieu considered various forms of government. In a tyrannical system, people are prompted not by freedom of choice or any expression of public virtue but, instead, by the sheer coercive power of the state, whether by decree of an individual despot or an unaccountable rogue regime. That's no way for human beings to live. There's life under such a system, yes, but not much liberty or pursuit of happiness; even life itself is threatened.

Montesquieu concluded that the best form of government is a self-governing one, and yet it is also the most difficult to maintain because it demands a virtuous populace. As noted by John Howard—the outstanding senior fellow at the Howard Center for Family, Religion, & Society—Montesquieu noted that each citizen in a self-governing state must voluntarily abide by certain essential standards of conduct: lawfulness, truthfulness, honesty, fairness, respect for the rights and well-being of others, obligation to one's spouse and children, to name a few.

Read the entire essay on the Center for Vision and Values website.

On Ignatius Insight:

• Out of Virtue, Greatness: Washington as Aristotle's Magnanimous Man | Dr. Jose Yulo

• Do We Deserve To Be Free? On The Fourth of July, 2006 | Fr James V. Schall, S.J.

• What Is America? | G.K. Chesterton

• On Being Catholic American | Joseph A. Varacalli

• Philosopher of Virtue | Josef Pieper (1904-1997)

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers