Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 186

November 6, 2012

SSPX Dialogue Continues: “Patience, Serenity, Perseverance, and Trust are Needed”

SSPX Dialogue Continues: “Patience, Serenity, Perseverance, and Trust are Needed” | Michael J. Miller | Catholic World Report

The last several months’ developments in Vatican/SSPX relations have been misinterpreted by extremists of all ideological stripes.

The

last official meeting between the Ecclesia

Dei Commission and the authorities of the Society of Saint Pius X took

place in the offices of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith on June

13, 2012. Some sanguine observers expected the return of the Society to the

fold in months if not weeks, while the more cynical opined that the meeting

marked the end of the CDF-SSPX negotiations.

Since

June there were major personnel changes at the CDF, and the Society held a

General Chapter, defined the parameters for its future dealings with the

Vatican, and neutralized an internal threat to its unity. Commentators weighed

each of these developments in turn as though it could seal the ultimate fate of

the Society. Often lost in the shuffle was the key fact that the SSPX

authorities still had not responded officially to Rome’s latest offer—a fact

helpfully pointed out in a communiqué from the Ecclesia Dei Commission issued in late October.

This

article reviews these events and offers a perspective on the controversies

surrounding them.

A new phase of discussions

At

the June 13 meeting at the Vatican Cardinal William J. Levada, then-prefect of

the CDF, presented to Bishop Bernard Fellay, superior general of the SSPX, a doctrinal

declaration and a proposal for the canonical regularization of the Society. The

first document was the most recent form of the “Doctrinal Preamble” drawn up by

the Ecclesia Dei Commission in late

2011; the acceptance by the SSPX of the principles stated therein was to be the

basis for any arrangement to reinstate the Society in the Church with a

canonical mission. It was understood that the Society could modify the wording

but not the substance of the Doctrinal Preamble; as of June 2012 the SSPX

authorities were waiting for Rome’s response to a version that they had

proposed.

They

were surprised, therefore, that the “Doctrinal Declaration” presented for them

to sign on June 13 was almost identical to the original Preamble. They were

even more perplexed by the canonical proposal. When the Society began its

doctrinal discussions with the CDF, it assured its members that there would be

no talk about regularizing its canonical status until after the doctrinal

issues were settled. Now Rome was asking for both at once. Bishop Fellay and

his assistants prudently deferred their response to Rome’s proposal until they

had the opportunity to consult widely with other SSPX members.

November 5, 2012

On Faithful Citizenship

[Editor's note: The following is a homily given by Fr. Tran on Sunday, October 28th. It is posted here as part of Catholic World Report's desire to contribute to the discussion regarding principles of responsible citizenship among Catholics.]

For the past 41 years, the Catholic Church in America has celebrated October as

Respect Life Month. This is a month in which our bishops have asked us to

reflect upon, pray about, and renew our commitment to the defense of all human

life. Today, I should like to address this issue vis-à-vis our civic duties as

Catholic Americans.

Three months ago, I preached on our moral obligation “to pay taxes, to exercise

the right to vote, and to defend [our] country” (CCC 2240). In

that homily, I said that we are Catholic Americans; we are not American

Catholics. In the term American Catholic, American is the adjective, which

means that it qualifies the noun Catholic. To qualify our Catholicism is to

qualify our faith, to qualify our allegiance to our Creator, to qualify our

love for our heavenly Father. Those things we do not qualify, hence, we are not

American Catholics.

In the term Catholic American, Catholic is the adjective, which means that it

qualifies the noun American. As Catholics, our patriotism is tempered by our

faith, our love of country is subordinated to our love of God, our decisions in

the body politic and our actions in the public square are all determined by a

conscience informed by faith. That is what it means to be a Catholic American.

As Catholic Americans, our Church teaches us that responsible citizenship is a

virtue, and participation in political life is a moral obligation (cf. Forming

Consciences for Faithful Citizenship). If a

Catholic conscience obliges us to participate in political life, then it stands

to reason that we must participate in a way that is consistent with our

Catholic faith. When it comes to matters that are purely political, then there

is a great deal of latitude in our prudential judgments. This is the purpose of

political dialogue. How much should people be taxed? What should the speed

limit be? Should there be a minimum wage, and if so, what should it be? What

are just immigration laws? There are many sides to these issues and men of good

will differ in their opinions. Healthy political debate will hash out these

issues for any particular country. The Church only gives us moral guidelines to

form our Catholic conscience when engaging in these debates. She gives us the

pale, if you will, that we should not step beyond in our political discourse.

Within the pale, however, there is much room for disagreement and political

discourse. After all, human governments are human institutions, hence, they

cannot be perfect. There is usually not one correct answer.

The fundamental principle that under girds our political discourse, however, is

respect for the dignity of the human person. Governments exist to protect the

common good—to protect people because of our inherent dignity as beings created

in the imago Dei, the image and

likeness of God. 6. In 1998, the American bishops stated this principle thus:

“Any politics of human dignity must seriously address issues of racism,

poverty, hunger, employment, education, housing, and health care. Therefore,

Catholics should eagerly involve themselves as advocates for the weak and

marginalized in all these areas.

Catholic public officials are obliged to address each of these issues as they

seek to build consistent policies which promote respect for the human person at

all stages of life. But being ‘right’ in such matters can never excuse a wrong

choice regarding direct attacks on innocent human life. Indeed, the failure to

protect and defend life in its most vulnerable stages renders suspect any

claims to the ‘rightness’ of positions in other matters affecting the poorest

and least powerful of the human community” (Living the Gospel of

Life: A Challenge to American Catholics,

23). In other words, since the issues of racism, poverty, hunger, employment,

etc., are fundamentally issues of respect for human dignity, it is logically

inconsistent that one could be right on those issues while wrong on respecting

the dignity of the most innocent and vulnerable human life, the unborn and the

elderly. “You believe I have a right to an education, but I don’t have a right

to life?” “You believe I have a right to housing, but I don’t have a right to

life?” “You believe I have a right to health care, but I don’t have a right to

life?” “Well, how do I get those things if I’m not alive?” This is what the

bishops meant when they said, “the failure to protect and defend life in its

most vulnerable stages renders suspect any claims to the ‘rightness’ of

positions in other matters affecting the poorest and least powerful of the

human community.”

The Homosexually Oriented Person and the Church

The Homosexually Oriented Person and the Church | Steven Schultz | Homiletic & Pastoral Review

Holding that all persons are created in the image and likeness of God, the Church most certainly does not condemn homosexual persons … (but) condemns using human sexuality for purposes contrary to that for which it is divinely intended … including homosexual acts. … It is the act, not the person which is the issue.

Despite the “glamorization” of homosexuality in modern society, we do

not serve the good of our fellow man by encouraging this approach.

Sacred Scripture clearly teaches that God does not condone homosexual

acts. 1 Consequently, the Church has consistently taught that homosexual acts are a violation of Catholic sexual ethics. 2

Unfortunately, those who advocate such acts attempt to ridicule

orthodox Church teaching by misstating authentic Church teaching as

condemning not simply acts, but homosexual persons themselves.

Holding that all persons are created in the image and likeness of God,

the Church most certainly does not condemn homosexual persons. The

Church condemns using human sexuality for purposes contrary to that for

which it is divinely intended, which includes engaging in homosexual acts. We must understand it is the act, not the person which is the issue. Let us considers this point in further detail.

Homosexuality is defined as “relations between men, or

between women, who experience exclusive or predominant sexual attraction

towards persons of the same sex.” 3

While the exact “causes” of homosexual orientation remain uncertain,

until relatively recently, most psychiatrists considered this

orientation an abnormal condition. In 1973, the American Psychiatric

Association changed its diagnostic manual to reflect the term “sexual

orientation disturbance.” This was modified in 1978 to “egodystoni”

(“distressful to the patient”); with all reference dropped in 1987. The

psychiatric community admitted at the time that this move did not “so

much reflect a scientific judgment on the cause or nature of

homosexuality, as the view that to label homosexuality as abnormal is to

stigmatize persons who are content with this condition, and to

encourage homophobia and discrimination against them.” 4

Note here that we are not “labeling” the person; we are speaking of

“orientation,” not person. Indeed, as the Congregation for the Doctrine

of the Faith (CDF) teaches, “the Church provides a badly needed context

for the care of the human person when she refuses to consider the person

as a ‘heterosexual’ or a ‘homosexual,’ and insists that every person

has a fundamental identity: the creature of God, and by grace, his child

and heir to eternal life.” 5

The importance of understanding human sexuality in the light of a

proper understanding of the human person, male and female, is a point to

which we shall return.

Let us first consider what Sacred Scripture explicitly teaches

regarding homosexual acts. We find numerous, clear admonishments of

homosexual acts in both the Old and New Testaments of Sacred Scripture.

Changing Catholic Attitudes about Cremation

Changing Catholic Attitudes about Cremation | Jim Graves | Catholic World Report

Since the ban on cremations was lifted in the 1960s, the practice has been on the rise among Catholics.

Cremation of human

remains was prohibited by Catholic authorities for much of the history of the

Church. Today, it is not only allowed, but growing in popularity among the

faithful, according to Monica Williams, Director of Cemeteries for the

Archdiocese of San Francisco. Nearly a third of Catholic families in the archdiocese

opt for cremation, she said, as more people come to accept it.

“It takes time for

family traditions to change,” Williams said. “More people are choosing cremation

as an alternative.”

While full-body

burial remains the Church’s preferred choice, there are practical reasons for

cremation. Cost is one; cremation can shave thousands off the $6,000-8,000 cost

of burial. Another is that families can inter cremated remains in family plots,

which have limited space. Some argue it is a more ecologically-friendly choice,

Williams said, as less open space and materials are required for cremation.

Church permits cremation

Cremation is the

process of reducing a body to bone fragments through the application of intense

heat. The bone fragments are then pulverized, placed in a container and

returned to the family. Regarding its morality, the Catechism of the Catholic Church devotes a single sentence to

cremation: “The Church permits cremation, provided that it does not demonstrate

a denial of faith in the resurrection of the body” (no. 2301).

The United States

Conference of Catholic Bishops, while noting that cremation is permitted,

stresses that the Church holds a preference for full-body burial. The USCCB

explained, “The Church’s reverence and care for the body grows out of a

reverence and concern for the person whom the Church now commends to the care

of God.… The human body is so inextricably associated with the human person

that it is hard to think of a human person apart from his or her body.”

Church authorities

banned the practice of cremation centuries ago to counter the ancient Roman

practice of cremating the body as a rejection of the existence of an afterlife.

Scripture teaches that man is made in the image and likeness of God

(Genesis 1:26-27), and therefore the body must be respected in both this life

and the next. The body is a temple of the Holy Spirit, and therefore, must be

treated with respect.

While cremation was

common in the ancient world, by the fifth century it had been largely abandoned

in the Roman Empire due to Christian influence. Today more than a third of

Americans opt for cremation; some nations, like Japan, have a nearly 100

percent cremation rate.

Maritain, Christianity, and Democracy

From a Thomistica.net interview with Dr. Raymond Dennehy about two recently re-issued works of Jacques Maritain’s political philosophy, Christianity and Democracy: The Rights of Man and The Natural Law (Ignatius Press; the book is also available as as electronic book download):

Thomistica.net: When were Christianity and Democracy and The Rights of Man and the Natural Law originally published?

Dr. Dennehy: Both works were published in French in New York by Editions de la Maison Francaise, Les Droits de l’ Homme et la Loi Naturelle in 1942 and Christianisme et Democratie in 1943.

Thomistica.net: Could

you tell us something about the context of these books? Why did Maritain

write them? How do they relate to his other work, including his other

work in political theory?

Dr. Dennehy: When the

outbreak of World War II made it impossible for Maritain and his wife to

return to France from his lecture tour in Canada and the United States,

he continued to support his countrymen by working with the Free French

in New York City. Through radio addresses and publications, he called

the attention of Americans to the condition of the French people,

appealing for food and money for French relief. Throughout the war,

Maritain also worked with the New School in New York City, producing

works of a more philosophical and scholarly nature on the subjects of

democracy, totalitarianism, and human rights, such as Les Droits de l ‘Homme et la Loi Naturelle; miniature editions of Christianisme et Democratie were dropped by British Royal Air Force planes over occupied France in 1944.

One way that these works relate to other

of Maritain’s works is that the theme of the relation between philosophy

and faith constitutes an idee fixe in his writings. Consider, for example, his Integral Humanism, the chapter in his Man and the State entitled “The Democratic Charter,” Scholasticism and Politics, and An Essay on Christian Philosophy.

Maritain was convinced that the ideals of modern democracy are

Christian in origin and that the values of Christianity energize its

institutions. (See my foreword in the Ignatius Press edition of Christianity and Democracy and The Rights of Man and the Natural Law for

an account of how Maritain sees the relation between faith and

speculative philosophy and faith and practical philosophy and thus for

what he understands the term “Christian philosophy” to mean.)

None of which diminishes Maritain’s

personal drama in reconciling faith and reason. Despairing of ever

finding truth (their teachers at the Sorbonne were skeptics and

materialists), Maritain and his wife, Raissa, entered into a suicide

pact: if they could not find meaning in materialism within one year,

they would kill themselves.

Read the entire interview. The second part of the interview is also available on the Thomistica.net site.

• Jacques Maritain on "Four Characteristics of a Society of Free Men", from Christianity and Democracy: The Rights of Man and The Natural Law.

• Jacques Maritain on the "the liquidation of the modern world", from the same work.

November 3, 2012

Faith-filled love and the greatest commandment

Readings:

• Dt 6:2-6

• Ps 18:2-3, 3-4, 47, 51

• Heb 7:23-28

• Mk 12:28-34

What is the most common subject of popular music? Answer: love.

The Beatles claimed “All We Need Is Love.” Robert Palmer confessed he

was “Addicted to Love.” “I Want To Know What Love Is” admitted the rock

group Foreigner. Mariah Carey had a “Vision of Love.” Queen pondered

that “Crazy Little Thing Called Love.” A full listing would require a

book.

But how many Top Forty songs have been about love for God? You don’t

need to be a music critic to recognize that the love referred to in most

pop and rock songs is either romantic love or something mistaken for

love: infatuation, sexual attraction, or simply lust. What so often

passes for love in our culture is actually the complete opposite of

authentic love. Instead of being sacrificial, it is self-seeking; rather

than giving, it takes; instead of long-suffering, it is short-term. As

Pope Benedict XVI remarked in his encyclical, “God Is Love” (Deus Caritas Est), “Eros,

reduced to pure ‘sex’, has become a commodity, a mere ‘thing’ to be

bought and sold, or rather, man himself becomes a commodity” (par. 5).

The love spoken of by Jesus in today’s Gospel is agape, that

is, the Holy Father states, a “love grounded in and shaped by faith”

(par. 7). When human love—whether love for a spouse, a child, a friend,

or one’s country—is informed, shaped, and filled with God’s love it

becomes whole and authentic. Put another way, it is rightly ordered to

its proper end, which is God.

The scribe who asked the

question, “Which is the first of all the commandments?” apparently did so out

of sincere curiosity. He posed the question after overhearing the dispute

between Jesus and the Sadducees over the general resurrection of the dead, a

belief the Sadducees denied (Mk 12:18-27). This scribe, like all scribes, was an expert in the

many technical details of applying the Mosaic Law in specific cases.

There were 613 commandments in the Law, so the answer to his question was not simple or obvious. In responding, Jesus referred immediately

and directly to the First Commandment: “Hear, O Israel! The Lord our God is Lord alone! You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your mind, and with

all your strength” (Mk 12:29-30; cf. Dt 6:5).

It was this commandment, more than any other, which marked the Hebrews as a unique, chosen people.

“Jesus united into a single precept this commandment of love for God,”

writes Pope Benedict, “and the commandment of love for neighbour found

in the Book of Leviticus: ‘You shall love your neighbour as yourself’

(19:18; cf. Mk 12:29-31). Since God has first loved us (cf. 1 Jn 4:10),

love is now no longer a mere ‘command’; it is the response to the gift

of love with which God draws near to us” (par. 1). How we treat

neighbors and strangers alike reveals something essential about our love, or lack of love,

for God. As the book of Deuteronomy states, "Cursed be he who perverts the justice due to the sojourner, the fatherless, and the widow", and, "Cursed be he who does not confirm the words of this law by doing them" (Dt 27:19, 26).

In speaking of Jesus’ response, the Holy Father emphasizes that this

love “is not simply a matter of morality.” After all, atheists can give

money to the poor and agnostics can build homeless shelters. “Being

Christian,” Benedict explains, “is not the result of an ethical choice

or a lofty idea, but the encounter with an event, a person, which gives

life a new horizon and a decisive direction” (par. 1).

Our love

is really love when it flows from the heart transformed by the One who

first loved us, who created us, and who gave His life for us. This love

is not abstract or academic but concrete and personal.

Love is so powerful because it God is love and He made us to be loved

and to love others. “God is love, and the one who abides in love abides

in God, and God abides in him” (1 Jn 4:16). Sadly, we live in a world

that is out of tune when it comes to real love. It is our joyful duty to

sing, with the Psalmist, “I love you, Lord, my strength!”

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in a slightly different form in the October 26, 2008, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

November 2, 2012

All Souls: A Day for Hope and Grief

All Souls: A Day for Hope and Grief | David Paul Deavel | Catholic World Report

The continuing connection of the dead to the living highlights the paradox at the heart of Catholic teachings on death.

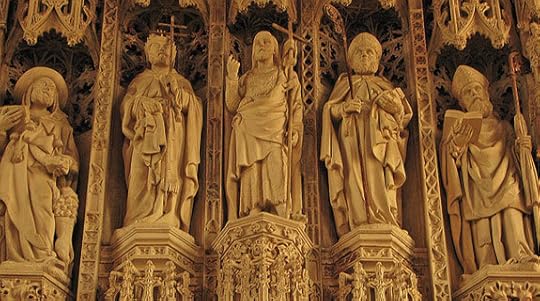

All Saints’ Day is one of those ecumenically happy events.

While some Protestants object to the Catholic practice of declaring specific

individuals saints in a way different from other people, most don’t have a

problem with celebrating the reality that is depicted in John’s glimpse of

heaven in the Book of Revelation—martyrs and virgins and great multitudes from

all nations praising the Lamb who was slain. Even the Protestants who reject

All Saints’ entirely and opt for “Reformation Day” generally tend to celebrate

a particular band of “saints” like Martin Luther and John Calvin who, they say,

returned Christianity to its pristine state.

All Souls’ Day, on the other hand, takes part in the

paradoxical nature of Catholic teaching on the reality of death.

This paradoxical nature, Catholics claim, comes directly

from the very foundations of Christianity. Jesus of Nazareth, building upon the

preaching of the Hebrew prophecies, proclaims to his audience that the Kingdom

of God is both here and now and…is coming soon. His resurrection from the dead

is the definitive sign that for human beings, death is no longer the last word.

Various cultures and religions have claimed that the soul survives death, but

the Christian claim is startlingly new. It’s not just that you will exist as a

lonely soul floating around in a dark, dank land of the dead, as so many of the

ancient civilizations believed. It’s that you will be given a new and

imperishable body. Your dead body, says St. Paul, echoing Jesus himself, is

like a kernel of wheat “buried” in the ground. The transformation that takes

place from seed to plant is like that from an earthly body to a heavenly

resurrected body. In view of this reality, St. Paul writes to the infant Church

gathered at the Greek city of Corinth, quoting the Hebrew Prophets Isaiah and

Hosea: “‘Death is swallowed up in victory.’ ‘O death, where is they victory? O

death where is thy sting?’” (1 Corinthians 15:54-5).

And even before that marvelous day of the final

Resurrection, it is still true, says St. Paul, that to be “away from the body”

is to be “at home with the Lord” (2 Corinthians 5:8)—and is thus a good thing.

Thus, one side of the argument, and a strong one at that, echoing down through

the centuries, is that death is indeed a good

thing, something to be celebrated and not grieved. The Mass is itself a

memorial not just of Christ’s death but also his resurrection. “We are a

resurrection people,” said St. Augustine (354-430) in one of his homilies. The

significance of death is that one has entered into the presence of God and is

now preparing for the resurrection.

To Trace All Souls Day

To Trace All Souls Day | Fr. Brian Van Hove, S.J. | Ignatius Insight

As

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger once said so well, one major difference between

Protestants and Catholics is that Catholics pray for the dead:

"My view is that if Purgatory did

not exist, we should have to invent it." Why?

"Because few things are as

immediate, as human and as widespread—at all times and in all

cultures—as prayer for one"s own departed dear ones." Calvin, the

Reformer of Geneva, had a woman whipped because she was discovered praying at

the grave of herson and hence was guilty, according to Calvin, of

superstition". "In theory, the Reformation refuses to accept Purgatory, and

consequently it also rejects prayer for the departed. In fact German Lutherans

at least have returned to it in practice and have found considerable

theological justification for it. Praying for one's departed loved ones is a

far too immediate urge to be suppressed; it is a most beautiful manifestation

of solidarity, love and assistance, reaching beyond the barrier of death. The

happiness or unhappiness of a person dear to me, who has now crossed to the

other shore, depends in part on whether I remember or forget him; he does not

stop needing my love." [1]

Catholics are not the only ones who pray for the dead.

The custom is also a Jewish one, and Catholics traditionally drew upon the

following text from the Jewish Scriptures, in addition to some New Testament

passages, to justify their belief:

Then Judas assembled his army and

went to the city of Adulam. As the seventh day was coming on, they purified

themselves according to the custom, and they kept the sabbath there. On the

next day, as by that time it had become necessary, Judas and his men went to

take up the bodies of the fallen and to bring them back to lie with their

kinsmen in the sepulchres of their fathers. Then under the tunic of every one

of the dead they found sacred tokens of the idols of Jamnia, which the law

forbids the Jews to wear. And it became clear to all that this was why these

men had fallen. So they all blessed the ways of the Lord, the righteous Judge,

who reveals the things that are hidden; and they turned to prayer, beseeching

that the sin which had been committed might be wholly blotted out. And the

noble Judas exhorted the people to keep themselves free from sin, for they had

seen with their own eyes what had happened because of the sin of those who had

fallen. He also took up a collection, man by man, to the amount of two thousand

drachmas of silver, and sent it to Jerusalem to provide for a sin offering. In

doing this he acted very well and honourably, taking account of the

resurrection. For if he were not expecting that those who had fallen would rise

again, it would have been superfluous and foolish to pray for the dead. But if he

was looking to the splendid reward that is laid up for those who fall asleep in

godliness, it was a holy and pious thought. Therefore he made atonement for the

dead, that they might be delivered from their sin. [2]

Besides the Jews, many ancient

peoples also prayed for the deceased. Some societies, such as that of ancient

Egypt, were actually "funereal" and built around the practice. [3] The urge to

do so is deep in the human spirit which rebels against the concept of

annihilation after death. Although there is some evidence for a Christian

liturgical feast akin to our All Souls Day as early as the fourth century, the

Church was slow to introduce such a festival because of the persistence, in

Europe, of more ancient pagan rituals for the dead. In fact, the Protestant

reaction to praying for the dead may be based more on these survivals and a

deformed piety from pre-Christian times than on the true Catholic doctrine as

expressed by either the Western or the Eastern Church. The doctrine of

purgatory, rightly understood as praying for the dead, should never give

offense to anyone who professes faith in Christ.

When we discuss the Feast of All Souls, we look at a

liturgical commemoration which pre-dated doctrinal formulation itself, since

the Church often clarifies only that which is being undermined or threatened.

The first clear documentation for this celebration comes from Isidore of

Seville (d. 636; the last of the great Western Church Fathers) whose monastic

rule includes a liturgy for all the dead on the day after Pentecost. [4] St.

Odilo (962-1049 AD) was the abbot of Cluny in France who set the date for the

liturgical commemoration of the departed faithful on November 2.

Before that, other dates had been seen around the

Christian world, and the Armenians still use Easter Monday for this purpose. He

issued a decree that all the monasteries of the congregation of Cluny were

annually to keep this feast. On November 1 the bell was to be tolled and

afterward the Office of the Dead was to be recited in common, and on the next

day all the priests would celebrate Mass for the repose of the souls in

purgatory. The observance of the Benedictines of Cluny was soon adopted by

other Benedictines and by the Carthusians who were reformed Benedictines. Pope

Sylvester in 1003 AD approved and recommended the practice. Eventually the

parish clergy introduced this liturgical observance, and from the eleventh to

the fourteenth century it spread in France, Germany, England, and Spain.

Finally, in the fourteenth century, Rome placed the

day of the commemoration of all the faithful departed in the official books of

the Western or Latin Church. November 2 was chosen in order that the memory of

all the holy spirits, both of the saints in heaven and of the souls in

purgatory, should be celebrated in two successive days. In this way the

Catholic belief in the Communion of Saints would be expressed. Since for

centuries the Feast of All the Saints had already been celebrated on November

first, the memory of the departed souls in purgatory was placed on the

following day. All Saints Day goes back to the fourth century, but was finally

fixed on November 1 by Pope Gregory IV in 835 AD. The two feasts bind the

saints-to-be with the almost-saints and the already-saints before the resurrection

from the dead.

Incidentally, the practice of priests celebrating

three Masses on this day is of somewhat recent origin, and dates back only to

ca. 1500 AD with the Dominicans of Valencia. Pope Benedict XIV extended it to

the whole of Spain, Portugal, and Latin America in 1748 AD. Pope Benedict XV in

1915 AD granted the "three Masses privilege" to the universal Church. [5]

On All Souls Day, can we pray for those in limbo? The

notion of limbo is not ancient in the Church, and was a theological extrapolation

to provide explanation for cases not included in the heaven-purgatory-hell

triad. Cardinal Ratzinger was in favor of its being set aside, and it does not

appear as a thesis to be taught in the new Universal Catechism of the Catholic

Church. [6]

The doctrine of Purgatory, upon

which the liturgy of All Souls rests, is formulated in canons promulgated by

the Councils of Florence (1439 AD) and Trent (1545-1563 AD). The truth of the

doctrine existed before its clarification, of course, and only historical

necessities motivated both Florence and Trent to pronounce when they did.

Acceptance of this doctrine still remains a required belief of Catholic faith.

What about "indulgences"? Indulgences from the

treasury of grace in the Church are applied to the departed on All Souls Day,

as well as on other days, according to the norms of ecclesiastical law. The

faithful make use of their intercessory role in prayer to ask the Lord"s mercy

upon those who have died. Essentially, the practice urges the faithful to take

responsibility. This is the opinion of Michael Morrissey:

Against the common juridical and

commercial view, the teaching essentially attempts to induce the faithful to

show responsibility toward the dead and the communion of saints. Since the

Church has taught that death is not the end of life, then neither is it the end

of our relationship with loved ones who have died, who along with the saints

make up the Body of Christ in the "Church Triumphant."

The diminishing theological interest

in indulgences today is due to an increased emphasis on the sacraments, the

prayer life of Catholics, and an active engagement in the world as constitutive

of the spiritual life. More soberly, perhaps, it is due to an individualistic

attitude endemic in modern culture that makes it harder to feel responsibility

for, let alone solidarity with, dead relatives and friends. [7]

As with everything Christian, then, All Souls Day has

to do with the mystery of charity, that divine love overcomes everything, even

death. Bonds of love uniting us creatures, living and dead, and the Lord who is

resurrected, are celebrated both on All Saints Day and on All Souls Day each

year.

All who have been baptized into

Christ and have chosen him will continue to live in Him. The grave does not impede

progress toward a closer union with Him. It is only this degree of closeness to Him which we

consider when we celebrate All Saints one day, and All Souls the next.

Purgatory is a great blessing because it shows those who love God how they

failed in love, and heals their ensuing shame. Most of us have neither

fulfilled the commandments nor failed to fulfill them. Our very mediocrity

shames us. Purgatory fills in the void. We learn finally what to fulfill all of

them means. Most of us neither hate nor fail completely in love. Purgatory

teaches us what radical love means, when God remakes our failure to love in

this world into the perfection of love in the next.

As the sacraments on earth provide

us with a process of transformation into Christ, so Purgatory continues that

process until the likeness to Him is completed. It is all grace. Actively

praying for the dead is that "holy mitzvah" or act of charity on our part which

hastens that process. The Church encourages it and does it with special consciousness

and in unison on All Souls Day, even though it is always and everywhere

salutary to pray for the dead.

ENDNOTES:

[1] See Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, The

Ratzinger Report: An Exclusive Interview on the State of the Church , with Vittorio Messori (San

Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1985) 146-147. Michael P. Morrissey says on the

point: "The Protestant Reformers rejected the doctrine of purgatory, based on

the teaching that salvation is by faith through grace alone, unaffected by

intercessory prayers for the dead." See his "Afterlife" in The Dictionary of

Catholic Spirituality,

ed. Michael Downey (Collegeville: Michael Glazier/Liturgical Press, 1993) 28.

[2] Maccabees 12:38-46. From The Holy Bible, Revised Standard Version,

Containing the Old and New Testaments. Catholic Edition. (London: The Catholic Truth Society,

1966) 988-989. Neil J. McEleney, CSP, adds: "These verses contain clear

reference to belief in the resurrection of the just...a belief which the author

attributes to Judas ...although Judas may have wanted simply to ward off

punishment from the living, lest they be found guilty by association with the

fallen sinners.... The author believes that those who died piously will rise

again...and who can die more piously than in a battle for God"s law? ...Thus,

he says, Judas prayed that these men might be delivered from their sin, for which

God was angry with them a little while.... The author, then, does not share the

view expressed in 1 Enoch 22:12-13 that sinned- against sinners are kept in a

division of Sheol from which they do not rise, although they are free of the

suffering inflicted on other sinners. Instead, he sees Judas"s action as

evidence that those who die piously can be delivered from unexpiated sins that

impede their attainment of a joyful resurrection. This doctrine, thus vaguely

formulated, contains the essence of what would become (with further precisions)

the Christian theologian's teaching on purgatory." See The New Jerome

Biblical Commentary, ed. Raymond E. Brown, SS, etal., art. 26, "1-2 Maccabees" (Englewood Cliffs,

N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1990) 446. Gehinnom in Jewish writings is more appropriately understood as a purgatory than a final destination of damnation.

[3] Spanish-speaking Catholics today

popularly refer to All Souls Day as "El Día de los Muertos", a relic of the

past when the pre- Christian Indians had a "Day of the Dead"; liturgically, the

day is referred to as "El Día de las Animas". Germans call their Sunday of the

Dead "Totensonntag". The French Jesuit missionaries in New France in the

seventeenth century easily explained All Souls Day by comparing it to the the

local Indian "Day of the Dead". The Jesuit Relations are replete with examples of how

conscious were the people of their duties toward their dead. Ancestor worship

was also well known in China and elsewhere in Asia, and missionaries there in

times gone by perhaps had it easier explaining All Souls Day to them, and

Christianizing the concept, than they would have to us in the Western world as

the twentieth century draws to a close.

[4] See Michael Witczak, "The Feast

of All Souls", in The Dictionary of Sacramental Worship, ed. Peter Fink, SJ, (Collegeville:

Michael Glazier/Liturgical Press, 1990) 42.

[5] "Three

Masses were formerly allowed to be celebrated by each priest, but one intention

was stipulated for all the Poor Souls and another for the Pope"s intention.

This permission was granted by Benedict XV during the World War of 1914-1918

because of the great slaughter of that war, and because, since the time of the

Reformation and the confiscation of church property, obligations for

anniversary Masses which had come as gifts and legacies were almost impossible

to continue in the intended manner. Some canonists believe Canon 905 of the New

Code has abolished this practice. However, the Sacramentary, printed prior to the Code,

provides three separate Masses for this date." See Jovian P. Lang, OFM, Dictionary

of the Liturgy (New

York: Catholic Book Publishing Company, 1989) 21. Also see Francis X. Weiser, The

Holyday Book (New

York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1956) 121-136.

[6] Ratzinger stated: "Limbo was

never a defined truth of faith. Personally—and here I am speaking more as

a theologian and not as Prefect of the Congregation—I would abandon it

since it was only a theological hypothesis. It formed part of a secondary

thesis in support of a truth which is absolutely of first significance for

faith, namely, the importance of baptism. To put it in the words of Jesus to

Nicodemus: "Truly, truly, I say to you, unless one is born of water and the

Spirit, he cannot enter the Kingdom of God" (John 3:5). One should not hesitate

to give up the idea of "limbo" if need be (and it is worth noting that the very

theologians who proposed "limbo" also said that parents could spare the child

limbo by desiring its baptism and through prayer); but the concern behind it

must not be surrendered. Baptism has never been a side issue for faith; it is

not now, nor will it ever be." See Ratzinger, The Ratzinger Report, 147-148.

[7] Morrissey, "Afterlife" in The

Dictionary of Catholic Spirituality, 28-29.

This article was originally

published, in a slightly different form, as "To Trace All Souls Day," in The

Catholic Answer, vol. 8, no. 5 (November/December 1994): 8-11.

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles and Book Excerpts:

• On November: All Souls and the "Permanent Things" | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

• Death, Where Is Thy Sting? | Adrienne von Speyr

• Purgatory: Service Shop for Heaven | Reverend Anthony Zimmerman

• The Question of Hope | Peter Kreeft

• The Next Life Is a Lot Longer Than This One | Mary Beth Bonacci

• My Imaginary Funeral Homily | Mary Beth Bonacci

• Do All Catholics Go Straight to Heaven? | Mary Beth Bonacci

• Be Nice To Me. I'm Dying. | Mary Beth Bonacci

• Are God's Ways Fair? | Ralph Martin

• The Question of Suffering, the

Response of the Cross | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• The Cross and The Holocaust | Regis Martin

• From Defeat to Victory: On the Question of Evil | Alice von Hildebrand

Father Brian Van Hove, S.J., is the Chaplain to the Religious Sisters of Mercy of Alma, Michigan.

November 1, 2012

Saints, Sinners, and the Perspective of Eternity

Saints, Sinners, and the Perspective of Eternity | Carl E. Olson | Catholic World Report

Vatican II's "Dogmatic Constitution on the Church" is full of riches, if we just take the time to read the text.

“Beloved: See what love the Father has bestowed on us that

we may be called the children of God. Yet so we are.” — 1 John 3:1 (from the Epistle reading for

All Saints)

Almost ten years ago, I co-founded a men’s reading group

that meets monthly to discuss books about Catholic theology and spirituality,

Church history, and related topics. During that time, we’ve read books by

Augustine and Aquinas, Newman and de Lubac, Benedict XVI and Belloc, Pieper and

Shakespeare. A few months ago, we began reading some of the sixteen

documents of the Second Vatican Council, beginning with Lumen Gentium, the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church. Many of

the men—all of them serious, practicing Catholics—had not read the documents,

at least not from start to finish. Several remarked on how surprised they were

by the clarity, beauty, and depth of Lumen Gentium. A couple of them even admitted that the document was not at

all what they expected. “Why,” one asked, “didn’t I read this years ago?”

Years ago, a friend who worked for a small diocese told me

of a seminar he and the other employees in the chancellery office had to

attend. At different times, he told me, the guest speaker would hold a copy of

the documents of the Council and say, “And, as the Council explained…” and

then, closing the book, would proceed to say things that were, in many cases,

quite contrary to what the documents actually state. Or that badly skewed what

was actually put to paper. No one seemed to notice, and when he spoke to

co-workers later, none shared his concern. In fact, they were apparently

oblivious to what the texts state and what the Council intended to communicate

about a host of topics.

On this, the Solemnity of All Saints, followed by All Souls

tomorrow, I want to highlight just three passages from Lumen Gentium that pertain directly to being saints here on earth

and in the life to come.

The second paragraph of Lumen Gentium provides an overview of salvation history that is

echoed in the opening paragraph of the Catechism; it is also fleshed out, in more detail, in the

opening of Chapter II of the document (par 9, especially). The emphasis is, first,

on God’s initiative: as Creator, Father, and Savior. Great stress is placed on

the invitation to man to participate in God’s divine life, something stressed

in today’s Epistle reading from 1 John. The Council fathers wrote:

Cardinal Bernardin corrects Douglas Kmiec

A week ago, former U.S. ambassador Douglas Kmiec, a strong supporter of Sen. Obama in 2008, was interviewed by the Los Angeles Times. In the course of that interview, Kmiec stated, "The president

promotes social justice as if he were a Catholic." Here is the fuller context:

You are antiabortion; Obama is in favor of abortion rights. But you also see abortion as part of a broader policy position,

including issues like the death penalty, poverty and war. You don't

have a single-issue test for a candidate.

There is a

tradition we trace back to Joseph Cardinal Bernardin of Chicago, of the

seamless garment — all life issues are interrelated: abortion, capital

punishment, war, a family wage, the environment. You can't take these

things apart. More and more Catholics understand that, but some very

important Catholics are resistant.

People on all sides tend to run

to get the law on their side and then to say, "See? We're right." That

kind of smugness cuts off dialogue. If you have a message about the

sanctity of marriage or human life, deliver it to me. Move my heart. Change my

mind as I'm sitting in your congregation. Don't run to Sacramento or

Washington and put it in some statute and then say, "I'm right because

the law is on my side."

Everybody wants to solve [same-sex

marriage] with law. I don't need the state to define marriage for me. I

need the state to treat citizens equally, to give everyone the benefit

of the rule of law and not shape it to favor one side or the other. At

the same time, give individual churches the opportunity to define

marriage as they read their religious practices.

The president

promotes social justice as if he were a Catholic. I get in trouble when I

say that. I was fooled by one of my friends in the White House.

He called and said, "I want you to be the first to know Barack Obama

has converted to Catholicism." He let me talk for 10 minutes about how I

knew it was going to happen, and all the while, laughter is building on

the other side, and he said, "Isn't it April 1 in Malta as it is in the

U.S.?

Setting aside the matter of specific candidates (who come and go) and political parties (who change platforms from year to year), there are a couple of serious problems with Kmiec's presentation and analysis. First, there is a tradition much older than the one mentioned by Kmiec, a tradition rooted in the Ten Commandments, which comes down to us through Jesus Christ, the apostles, and the Church. There are legitimate points of criticism to be made when it comes to Cardinal Bernardin's "seamless garment" teaching, but they aren't of concern here, mostly because Kmiec isn't even true to the teaching as Cardinal Bernardin expressed it.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers