Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 180

December 5, 2012

Requiescat in pace: Dave Brubeck, jazz giant and convert to Catholicism from "nothing"

Dave Brubeck, legendary jazz pianist and pioneer, died earlier today on the cusp of his 92nd birthday. From the Chicago Tribune:

Dave Brubeck, a jazz musician who attained pop-star acclaim with recordings such as "Take Five" and "Blue Rondo a la Turk," died Wednesday morning at Norwalk Hospital, in Norwalk, Conn., said his longtime manager-producer-conductor Russell Gloyd.

Brubeck was one day short of his 92nd birthday. He died of heart failure, en route to "a regular treatment with his cardiologist,” said Gloyd.

Throughout his career, Brubeck defied conventions long imposed on jazz musicians. The tricky meters he played in “Take Five” and other works transcended standard conceptions of swing rhythm.

The extended choral/symphonic works he penned and performed around the world took him well outside the accepted boundaries of jazz. And the concerts he brought to colleges across the country in the 1950s shattered the then-long-held notion that jazz had no place in academia.

As a pianist, he applied the classical influences of his teacher, the French master Darius Milhaud, to jazz, playing with an elegance of tone and phrase that supposedly were the antithesis of the American sound.

The New York Times has a lengthy obituary that highlights Brubeck's long, active, and prolific life as musician and composer:

In 1954 Mr. Brubeck was the first jazz musician to be featured on the

cover of Time magazine. That same year he signed with Columbia Records,

promising to deliver two albums a year, and built a house in Oakland.

For all his conceptualizing, Mr. Brubeck often seemed more guileless and

stubborn country boy than intellectual. It is often noted that his

piece “The Duke” — famously recorded by Miles Davis and Gil Evans in

1959 on their collaborative album “Miles Ahead” — runs through all 12

keys in the first eight bars. But Mr. Brubeck contended that he never

realized that until a music professor told him.

Mr. Brubeck’s very personal musical language situated him far from the

Bud Powell school of bebop rhythm and harmony; he relied much more on

chords, lots and lots of them, than on sizzling, hornlike right-hand

lines. (He may have come by this outsiderness naturally, as a function

of his background: jazz by way of rural isolation and modernist

academia. He was, Ted Gioia wrote in his book “West Coast Jazz,”

“inspired by the process of improvisation rather than by its history.”)

It took a little while for Mr. Brubeck to capitalize on the greater

visibility his deal with Columbia gave him, and as he accommodated

success a certain segment of the jazz audience began to turn against

him. (The 1957 album “Dave Digs Disney,” on which he played songs from

Walt Disney movies, didn’t help his credibility among critics and

connoisseurs.) Still, by the end of the decade he had broken through

with mainstream audiences in a bigger way than almost any jazz musician

since World War II.

In 1958, as part of a State Department program that brought jazz as an

offer of good will during the cold war, his quartet traveled in the

Middle East and India, and Mr. Brubeck became intrigued by musical

languages that didn’t stick to 4/4 time — what he called “march-style

jazz,” the meter that had been the music’s bedrock. The result was the

album “Time Out,” recorded in 1959. With the hits “Take Five” (composed

by Mr. Desmond in 5/4 meter and prominently featuring the quartet’s

gifted drummer, Joe Morello) and “Blue Rondo à la Turk” (composed by Mr.

Brubeck in 9/8), the album propelled Mr. Brubeck onto the pop charts. ...

As a composer, Mr. Brubeck used jazz to address religious themes and to

bridge social and political divides. His cantata “The Gates of Justice,”

from 1969, dealt with blacks and Jews in America; another cantata,

“Truth Is Fallen” (1972), lamented the killing of student protesters at

Kent State University in 1970, with a score including orchestra,

electric guitars and police sirens. He played during the

Reagan-Gorbachev summit meeting in 1988; he composed entrance music for

Pope John Paul II’s visit to Candlestick Park in San Francisco in 1987;

he performed for eight presidents, from Kennedy to Clinton.

Much more about Brubeck's life and discography can be found on the All Music Guide site. As Deacon Greg Kandra points out (and I noted in this May 2011 post), Brubeck was also a convert, in 1980, to the Catholic Church. This 2009 article in St. Anthony Messenger states:

To Hope! A Celebration was Brubeck’s

first encounter with the Roman

Catholic Mass, written at a time when

he belonged to no denomination or

faith community. It was commissioned

by Our Sunday Visitor editor Ed Murray,

who wanted a serious piece on the

revised Roman ritual, not a pop or jazz

Mass, but one that reflected the American

Catholic experience.

The writing was to have a profound

effect on Brubeck’s life. A short time

before its premiere in 1980 a priest

asked why there was no Our Father

section of the Mass. Brubeck recalls

first inquiring, “What’s the Our Father?”

(he knew it as The Lord’s Prayer) and

saying, “They didn’t ask me to do that.”

He resolved not to make the addition

that, in his mind, would wreak havoc

with the composition as he had created

it. He told the priest, “No, I’m going on

vacation and I’ve taken a lot of time

from my wife and family. I want to be

with them and not worry about music.”

“So the first night we were in the

Caribbean, I dreamt the Our Father,”

Brubeck says, recalling that he hopped

out of bed to write down as much as he

could remember from his dream state.

At that moment he decided to add that

piece to the Mass and to become a

Catholic.

He has adamantly asserted for years

that he is not a convert, saying to be a

convert you needed to be something

first. He continues to define himself as

being “nothing” before being welcomed

into the Church.

His Mass has been performed

throughout the world, including in the

former Soviet Union in 1997 (when

Russia was considering adopting a state

religion) and for Pope John Paul II in

San Francisco during the pontiff’s 1987

pilgrimage to the United States. At the

latter celebration, Brubeck was asked to

write an additional processional piece

for the pope’s entrance into Candlestick

Park.

Again, it was a dream that led him to

accept a sacred music project that he

initially refused as not workable. The

dream “was more of a realizing that I

could write what I wanted for the

music,” Brubeck says.

“They needed nine minutes and they

gave me a sentence, ‘Upon this rock I

will build my Church and the jaws of

hell cannot prevail against it.’ So rather

than dream musically, I dreamed practically

that Bach would have taken one

sentence in a chorale and fugue, as he

often did, and that was the answer,” he

says. “So I decided that I would do that

piece for the pope,” which is known as

“Upon This Rock.”

If I might, here are some thoughts from a post I wrote last year on the "catholicity of jazz", with a reference to Brubeck:

Brubeck composed a piece, "To Hope! A Celebration Mass" in 1996 that seems to have a much more classical/European sound

to it. Regardless, I've long said that I never want to hear jazz at

Mass, now matter how well it is played or composed, for while jazz is

very beautiful, powerful, and even spiritual (in the best sense of that

word), it's very nature—improvisational, largely profane (in the correct

sense of that word)—is not well-suited, in my judgment, to liturgical

settings.

But I would also insist that outside of liturgical settings, good

jazz is good music, which means it is an artistic expression in keeping

with Catholicism, which prizes and recognizes all that is good, true,

and beautiful. Personal tastes differ, it goes without saying, and I can

only take a little bit of Ornette Coleman or Cecil Taylor before I turn

to the Blue Note albums of the 1950s and '60s, or the trio albums of

Keith Jarrett, or the recent works of Joshua Redman, Brad Mehldau, Roy

Hargrove, and so forth. Great jazz, to my mind and ear, is a marvelous

combination of structure and improvisation, where intelligent musical

conversation takes place upon a chosen, mutual theme, revealing both the

individual thoughts/voices of those participating, as well as the

deeper meaning and heart of the piece they are playing. It is a music

that recognizes and honors and draws upon tradition while speaking about

and within that tradition in the here and now. In my mind, jazz bears a

certain analogy to the human condition: we are creatures endowed with

great freedom, but freedom is to be exercised in pursuing the good,

recognizing and respecting the limits and boundaries of our nature and

of creation as established by God the Creator.

May God grant him eternal rest!

Benedict XVI reflects on God's benevolent plan and living in Advent

From Vatican Information Service:

Vatican City, (VIS) - God's "benevolent plan" for mankind, which begins

St. Paul's Letter to the Ephesians, was the theme of the Holy Father's

catechesis at today's general audience. The great hymn that the apostle

Paul raised to God "introduces us to living in the time of Advent, in

the context of the Year of Faith. The theme of this hymn of praise is

God's plan for mankind, defined in terms of joy, stupefaction and

thankfulness, ... of mercy and love", said the Pope.

The Apostle

elevated this blessing to God because he "looked upon his actions

throughout the history of salvation, culminating in the incarnation,

death and resurrection of Jesus, and contemplated how the celestial

Father chose us, even before the foundation of the world, to become His

adoptive children, in his only Son, Jesus Christ. ... God's 'benevolent

plan', which the Apostle also describes as a 'plan of love', is defined

as 'the mystery' of divine will, hidden and then disclosed in the Person

and work of Christ. The initiative precedes any human response; it is

the freely given gift of his love, which envelops and transforms us.

"What

is the ultimate aim of this mysterious plan? It is to recapitulate all

things in Christ; "this means that in the great design of creation and

history, Christ is placed at the centre of the world's entire path, as

the axis upon which everything turns, drawing all of reality to Him, in

order to overcome dispersion and limits, and to lead all to fullness in

God".

However, "this benevolent plan", explained Benedict XVI,

"did not remain concealed in God's silence, in the heights of His

Heaven; instead, He brought it to our knowledge by entering into a

relationship with man, to whom He revealed His very being. He did not

simply communicate a series of truths, but instead He communicated

Himself to us, He showed Himself as one of us, to the extent of taking

on human flesh. ... This communion in Christ, through the work of the

Holy Spirit, offered by God to all mankind in the light of His self-

revelation, does not merely correspond to our humanity, but is instead

the fulfilment of its deepest aspirations, and introduces it to a joy

which is neither temporal nor limited, but eternal".

"In view of

this, what is, then, the act of faith? It is man's response to God's

self-revelation, by which He shows His 'benevolent plan' for humanity.

... it is allowing oneself to be seized by God's Truth, a Truth that is

Love. ... All this leads to a ... true 'conversion', a 'change of

mentality', because the God Who has revealed Himself to us in Christ and

has shown us His plan captures us and draws us to Him, becoming the

meaning that sustains our life and the rock on which it finds

stability".

The Holy Father concluded by recalling that Advent

"places us before the luminous mystery of the coming of the Son of God

and the great 'benevolent plan' by which He sought to draw us to Him,

to allow us to live in full communion of joy and peace with Him. Advent

invites us, in spite of the many difficulties we encounter, to renew our

certainty of the presence of God: He came into the world, in human

flesh like ours, to fully realise his plan of love. And God asks that we

too become signs of His action in the world. Through our faith, hope

and charity, He wishes us to make His light shine anew in our night".

R.I.P.: American's demographic "exceptionalism"

Jonathan V. Last, editor of the Weekly Standard and author of the forthcoming book, What to Expect When No One's Expecting (Encounter, 2013), comments in his e-letter today about the recent report from the Pew Research Center about falling fertility rates in the U.S.:

Last week the general public had a momentary freak-out when it was reported that U.S. fertility rates had hit their lowest point since 1920. The news made it into the front pages of the Washington Post and USA Today and it was as if, for a moment, mainstream America awoke to the fact that our demographics are terrible. And getting worse.

But then the moment passed and everyone went back to worrying about the

fiscal cliff and the royal pregnancy. Such is the nature of media.

It's worth looking into the new numbers in a little more depth, though,

because they give you a reasonably good sense as to what's happening in

our society.

So here's the top-line: Between 2007 and 2010, the U.S. birthrate

dropped 8 percent, to the level of 64 births for every 1,000 women. The

preliminary data for 2011 shows it sliding still more, to 63.2. This is

as barren as America has ever been. For some contrast: During the Great

Depression—when it really collapsed—the birth rate bottomed out in the

high 70s. In the 1970s—when fertility rates all across the Western world

entered a death spiral—the birth rate never dipped much lower than 65.

Our birth rate is now lower than it was both during the greatest

economic calamity, and the greatest social upheaval, in modern American

history.

One striking (and sobering) aspect, Last notes, is that the birth rates among immigrants are not just falling, but are plummeting:

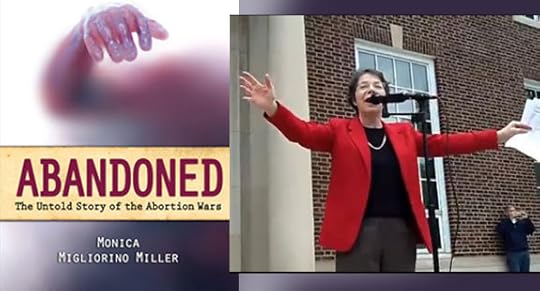

A Tale from the Front Lines of the Abortion Wars

A Tale from the Front Lines of the Abortion Wars | Mark Sullivan | Catholic World Report

A new book tells the story of a life lived fighting abortion.

“The time may come when we date the beginning of the collapse of the

Soviet system from the appearance of Gulag,”

wrote a German reviewer of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s masterpiece, The Gulag Archipelago, 1918-1956: An

Experiment in Literary Investigation. It may sound crazy, but the time may

also come when we date the end of legalized abortion in the United States from

the publication of Abandoned: The Untold

Story of the Abortion Wars by Monica Migliorino Miller (Saint Benedict

Press, 2012).

I recently began reading the abridged version of Gulag, and I was stuck by Solzhenitsyn’s descriptions of the

injustice and the powerlessness of the people in communist Russia—in

particular, by how fittingly his descriptions of the power structures of the

Soviet system could be applied to the institutions that promote and protect

legalized abortion in this country. I thought it would make an interesting

story, so I requested a review copy of Abandoned.

I thought it would make a good point of departure to talk about Solzhenitsyn.

I’ve never read a

whole book about abortion. I’m a “good” pro-lifer who will on occasion pass out

pro-life voting guides to his friends. I have a pro-life bumper sticker on my

car, and I’ve been to the March for Life in Washington, D.C. a few times. I

thought I knew all I needed to know about abortion, and that if I learned

anything more, I’d just get more upset and frustrated. At least that is what I

thought until I read Abandoned.

I couldn’t put it

down. It wasn’t what I expected. It is not an abstract book of philosophy,

biology, ethics, politics, or theology—even though Miller has her doctorate in

theology and teaches at Madonna University in Michigan. It’s not a rehash

of the same old pro-life rhetoric or arguments. This is the story of Miller’s

involvement in the pro-life movement in Chicago and Milwaukee from 1976 to

1993. Her activities were controversial and sometimes shocking, but she never

tells the reader what to do or think. The reader is forced to face the ugly

truth of abortion and then decide what he is going to do about it.

Miller has her

undergraduate degree in theater. She knows drama. She knows how to build scenes

and hold the reader’s attention. She kept a journal during her years of

pro-life work, so in writing this book, she was able to recreate scenes and

conversations that give you the “you are there” feel.

I keep thinking, “This book would make a great movie.” It is the

classic story of the underdog fighting the big bad bureaucracy to save the

innocent. It would be America’s version of Schindler’s

List, or Erin Brockovich with

more modest clothing. It may be a tough sell, but I’m hoping a pro-life movie

director will give it a try.

40% off Eva Muntean's "Employee Pick of the Week"

40% off Eva Muntean's Pick of the Week*

Unlike most of the others who have given their recommendations, I have no hesitation in picking my favorite book –

The Shadow of His Wings

.

Unlike most of the others who have given their recommendations, I have no hesitation in picking my favorite book –

The Shadow of His Wings

. While Ignatius Press has many wonderful and powerful books, this one is

my favorite by far (the only other one that comes close is Tony Ryan’s

recommended Fire Within).

When this book was first recommended to us, Fr. Fessio was the first to

read it. I remember how excited he was to tell us about it. His

enthusiasm was infectious so I asked for the manuscript. I was

completely mesmerized. I could not put it down and finished it in less

than two days. My first question was “is this real; could this have

really happened?” The feeling of excitement has not left me in the 12

years since we’ve published this book. I have recommended this book at

every opportunity - which is often since I work conferences for Ignatius

Press. I have had many people come back and tell me how much this book

has changed their lives.

There is no need to tell you about the story – you can read about it on

our website. Just know that it has it all: war, redemption, Nazis, guns

(to a bishop’s head by our hero), concentration camps, Himmler,

spiritual battles, miracles, Lourdes, and above all else, the astounding

stories of the power of prayer.

I have been working for Ignatius Press almost 20 years and in all that

time I have

never seen another book receive a personal write-up in our

never seen another book receive a personal write-up in our catalog (I wrote it). Check it out – it’s still the current product

description on our website. Once there, do yourself a favor and buy

(and read!) this wonderful book. The Shadow of His Wings is also available as an e-book.

Eva

Muntean, Marketing Manager, was born in Budapest, Hungary. Her family

escaped Communism in a trunk of a car through the Iron Curtain in 1967.

After a major spiritual “reversion” to her faith, she quit her secular

job and joined the Ignatius Press family in 1993. She is one of the

founders of the Walk for Life in San Francisco. She lives happily in her favorite city of San Francisco with her dog, Mia.

*Employee

Pick of the Week program features savings of 40% off a book, movie, or

compact disc personally chosen and recommended by an Ignatius Press

employee.

December 3, 2012

NPR's Mary: bitter, angry, and mad at Christians

Sure, National Public Radio did not publish novelist Colm Toibin's novella, The Testament Of Mary; it was published last month by Scribner. But NPR seems to love it. No, make that: NPR really loves it! There was a very sympathetic November 13th feature, "'Testament Of Mary' Gives Fiery Voice To The Virgin", then a glowing November 14th review, "A Vengeful Virgin In 'The Testament Of Mary'", then an excerpt from the book, and (finally, for now) an interview with Toibin, "A New 'Testament' Told From Mary's Point Of View",

posted today. I'm not sure how many NPR pieces there are about the

Pope's new book, but I doubt it's more than three, at the very most.

What

is Tolbin's gimmick? And, yes, it is a gimmick, no matter how literate,

thoughtful, deep, anguished, and intellectual NPR tries to make it

sound. Here are some of the pertinent bits of information, gleaned from

the ever-informative NPR pieces:

In his new novel, The Testament of Mary, Irish writer Colm

Toibin imagines Mary's life 20 years after the crucifixion. She is

struggling to understand why some people believe Jesus is the son of

God, and weighed down by the guilt she feels wondering what she might

have done differently to alter — or ease — her son's fate.

Toibin

grew up Catholic and, for a time, considered joining the priesthood.

This changed upon his arrival at university, however, when exposure to

new people and ideas soon led him to lose his faith. "I suppose I had

been moving toward it without knowing," Toibin tells Fresh Air's Terry Gross, "but, yeah, it went very quickly."

It

was around this time, too, that Toibin acknowledged his homosexuality.

Growing up, he says, "there was no word for it," and he describes his

feelings as "absolute confusion." It was after meeting an openly gay

friend at university, he explains, that "I moved very gingerly from

between being a very conservative boy from a small town and being out

with some friends."

And from the review:

The work is pointedly not called a gospel — good news — but a

testament — a giving witness to, an attestation. "I was there," she

says. And, having seen the Crucifixion, the Mother of God tells the

apostles: "I can tell you now, when you say that he redeemed the world, I

will say that it was not worth it."

Much of the elegance of

this novella comes from its language, which is poetic but spare, much

like cryptic music of the Gospels. And, as in the Gospels,

understatement and implication are used to great effect. Most

expressively, the name "Jesus" is never used — not once. Neither is

Christ. Instead, Mary calls him "my son" or "him" or even "the one who

was here." Part of this is her pain — she cannot bear to say the name —

but part of it is also a refusal to contribute to the narrative of the

man named Jesus Christ.

Toibin leaves the most important questions unanswered: Did he cure

the sick? Raise the dead? Turn water into wine? Mary only hears

stories.

And from the author himself:

A selection from "Set All Afire: A Novel about Saint Francis Xavier" by Louis de Wohl

A Selection From Book Four of Set All Afire: A Novel about Saint Francis

Xavier | Louis de Wohl | Ignatius Insight | Part One | Part Two

The names of the villages they passed were of the same ilk. Alantalai,

Periytalai, Tiruchendur, Talambuli, Virapandianpatnam, Punaikayal,

Palayakayal, Kayalpamam and Kombuturé.

He did not stick to his original idea, to start working only

when he had reached Tuticorin. He could not wait. It was bitter

to see the shrines and temples on the way, with obscene gods of

stone performing obscene actions on temple friezes, with phallic

symbols abounding; bitter to see trembling villagers watching

overfed cows eating all their food without daring to disturb the

sacred animals; bitter to hear that the pearl fishers paid a good

percentage of their catch to sorcerers for spells and talismans

against the bite of sharks, and paid still more for mantrams against

any other kind of danger, trouble and illness.

At Kombuturé they told him about a woman who had been

three days in labor and was dying, although her husband had paid

the sorcerer for all the aid he could give and the house was full

of mantrams of all kinds.

Coelho shook his head sadly. "The demons are more powerful

than the sorcerer and the mantrams", he murmured.

Francis exploded. "Where is that house?" he asked.

Coelho and the other two students tried to hold him back, but

they might as well have tried to stop the monsoon with their hands.

Francis stalked into the house.

The sorcerer, with two apprentices, was squatting on the floor;

all three of them were drumming on some kind of musical instruments

and chanting invocations at the top of their voices. They had

put a kettle on the floor, filled with some burning substance

that sent up clouds of stinking smoke. In a corner of the room

the husband and at least half a dozen youngsters of all ages were

crouching, moaning and rolling their eyes in abject fear.

A grotesque figure of clay and half a dozen mantrams were tied

to the body of the suffering woman.

Francis took one look. Then he seized the kettle and swung it

at the sorcerer and his helpers. They did not wait for what might

happen next, but jumped up and raced out. Francis threw the kettle

after them, untied the idol and the mantrams and threw them out

as well.

A midwife, sitting at the feet of the woman, looked up at him

as if she were seeing a demon. The woman herself kept her eyes

closed. Now that the noise had subsided, Francis could hear her

moaning softly.

He knew nothing of childbirth. The hospitals in which he had

nursed his patients in Paris, Venice, Lisbon and Goa were only

for men. He thought the woman was dying, as he had been told that

she was. She certainly looked as if she were dying. And into a

dying woman's room he brought his Lord. It was all he could do

and all he set out to do.

"Coelho— translate. Tell her that I am coming in the

name of the Lord who made heaven and earth..."

Coelho's lips were trembling a little. Perhaps Father Francis

was not quite aware of the risk they were taking. Now if the woman

died, as surely she would, the sorcerer would say that it was

all the fault of these interfering strangers...

"Translate", ordered Francis. "I command you."

Coelho translated. The woman opened her eyes. She fastened her

gaze not on Coelho but on the strange face of the white man with

its complete absence of fear, with its tranquil smile. Being a

woman, she recognized love when she saw it.

"Tell her, Our Blessed Lord wants her to live with him forever.

Tell her what he wants her to believe. Visuvasa manthiram—paralogathiyum

...."

She stared at Francis. Her lips moved a little and then she echoed

his smile.

"Are you ready to accept what you have heard?" asked

Francis gently, when Coelho had finished translating the last

part of the Creed. "Can you believe it?"

Oh yes, she could. She could.

He took the New Testament out of his pocket and read out the

story of the birth of the Christ Child. Coelho translated again.

From time to time he looked towards the entrance of the house.

The crowd outside was growing larger and larger. They would never

get away alive. He was sweating. But he went on translating.

"Water", said Francis. When they brought it to him,

he baptized the woman.

Coelho, looking on, prayed for all he was worth. In a state of

utter confusion he implored God to save their lives, to save the

woman, to prevent the sorcerer from making the villagers storm

the hut, to have mercy on him, on Father Francis—on everybody.

A sudden tremor went through the body of the woman, she threw

back her head and gave a loud cry. Instantly the midwife sprang

up.

Francis took a step backwards.

At first he did not know that labor had started again after hours

of interruption. But he knew it soon enough.

Minutes later the child was there, and a few seconds later yelling

lustily.

Outside the villagers broke into a howl of enthusiasm that shook

the hut.

Two hours later Francis had baptized the husband, three sons,

four daughters and the newly born infant, another son.

Coelho was grinning from ear to ear.

But for Francis this was no more than the beginning. He stepped

outside, where the villagers were still howling their joy to heaven

and asked for the headman. Coelho had to tell him that Father

Francis wanted the entire village to accept Jesus Christ as their

God and Lord.

The headman scratched himself thoughtfully. They would do so

gladly, but they could not—not without the permission of

the Rajah.

"Where is that Rajah?" asked Francis curtly.

Coelho passed on the question. The Rajah was far away, very far

away, but there was an official here, who represented him. He

had come to collect the taxes for his master.

Francis went to see him at once.

The tax collector was at first a little suspicious. If these

people accepted this new belief, would they still be willing to

pay their taxes to the Rajah? They would? Well...

Francis began to explain the tenets of Christianity to the man

who listened politely. In the end he gave permission in the name

of his master. He himself? No, no. This new thing seemed very

good, but he himself could not accept it. He was the Rajah's man.

The Rajah would have to give the order to him personally.

"It is a pitee—a great pitee", said Coelho, when

the man withdrew, rather hastily. "We could have called him

Matthew."

It took all next day to baptize every man, woman and child of

the village and two days more to tell them at least the rudiments

of what they must know.

As they left, they saw the woman with her newborn babe in her

arms standing in the door of the hut, smiling at them and making

the sign of the Cross.

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Book Excerpts:

• All Louis de Wohl novels published by Ignatius

Press

• Chapter One of The Spear: A Novel | Louis de Wohl

• Chapter One of The Living Wood: Saint Helena and the Emperor Constantine (A Novel) | Louis de Wohl

• Chapter One of Citadel of God: A Novel About Saint

Benedict | Louis de Wohl

Louis de Wohl (1903-1961) was a distinguished and internationally respected

Catholic writer whose books on Catholic saints were bestsellers worldwide.

He wrote over fifty books; sixteen of those books were made into films.

Pope John XXIII conferred on him the title of Knight Commander of the Order

of St. Gregory the Great.

• Read

de Wohl's thoughts about being a Catholic and a novelist.

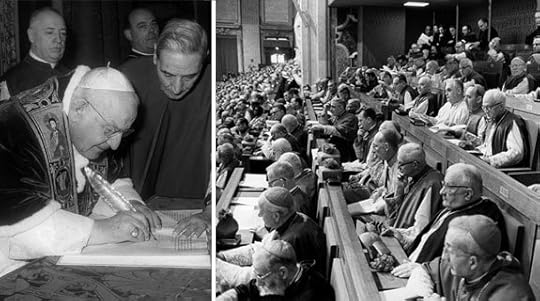

The True Spirit of Vatican II

The True Spirit of Vatican II | Douglas G. Bushman, S.T.L. | Catholic World Report

The

main desire of the Council was to reinvigorate the Church’s mission of

promoting a fully human life in Jesus Christ.

As far as I know, no participant in the Second Vatican Council summed up its

goals or described its spirit as addressing the question whether God’s truth

and love are effective, that is, whether they have the power to steer men on a

course conforming to their dignity. Nevertheless, the overarching question that

the Council did address leads to this question. For the Council Fathers the

question was: “Ecclesia, quid dicis de te ipsa? Church, what do you say about

yourself?” The context of the question is determinative of the Council’s

pastoral nature. The concern was not to produce a technical treatise of

ecclesiology, but to respond to the spreading perception that the Church is no

longer relevant, that it has nothing to offer to a humanity that has taken its

future and the aspiration for a better world into its own hands.

Why the

Council?

Just a few years after upheaval of World War II, with the Cold War coming to a

head in the Cuban Missile Crisis, with historic revolutions taking place in

technology, science, politics, economics, and culture, the Church found herself

in a position similar to that of John the Baptist. He lived differently than

his contemporaries, putting God first in every way, and he spoke with the

authority of a prophet. He did this in the name of fidelity to the God who

called him and fidelity to the vocation that God entrusted to him. He had a

message, a lifestyle went with it, and a baptism of repentance that attracted

great crowds. He could not be ignored. Everything about him provoked the

question: “Quid dicis de te ipso? What do you say about yourself?” (Jn 1:22).

This is

precisely the question put to the Church at the time of Vatican II: Can you

give an account of yourself, of your convictions and values and way of life, at

a time when these are increasingly at odds with the surrounding culture and increasingly

treated as irrelevant?

Could a Church that was so old, that had been there all along the way and

evidently did not prevent the unprecedented assaults on human dignity of the

twentieth century, make a credible case that it has something positive to

offer? If, in looking to the past, this Church must acknowledge that its own

members contributed to division among Christians and to a defensive, even

hostile stance in relation to science and the modern democratic states, can

this Church dare to say that it is not only not part of the problem but has a

solution to offer? Is it not audacious for this Church, and thus contrary to

the humility that it professes, to say to the world, in the words of Pope Paul

VI: “I have that for which you search, that which you lack” (Ecclesiam Suam, 95)?

The Church’s response to the crisis of humanity as it manifested itself in the

middle of the twentieth century parallels what John’s Gospel says about the

Baptist: “He came for testimony, to bear witness to the light, that all might

believe through him. He was not the light, but came to bear witness to the

light. The true light that enlightens every man was coming into the world” (Jn

1:7-9). The first words of the Council’s central document on the Church begin

with this theme.

Christ is the Light of nations. Because this is so, this Sacred

Synod gathered together in the Holy Spirit eagerly desires, by proclaiming the

Gospel to every creature, to bring the light of Christ to all men, a light

brightly visible on the countenance of the Church (Lumen gentium, 1).

The

Church’s mission is to point to Christ. She does this most effectively by

reflecting His eternal light, and that light shines especially conspicuously in

times of darkness. In his encyclical convoking the Council, Humanae salutis, Pope John XXIII envisioned that the Council would

result in “vivifying the temporal order with the light of Christ.” The

brutalities of the twentieth century had demonstrated what can happen in the

name of progress and development that deliberately exclude any reference to God

and set themselves against the Church. This could only constitute an urgent

call for the Church, who knows when men do not acknowledge God neither are they

able to acknowledge human dignity or set any limits to their own power and

action. What was needed was a counter-demonstration.

Continue reading at www.CatholicWorldReport.com.

December 1, 2012

Advent orients us to the heart of the Nativity

Readings:

• Jer 33:14-16

• Ps 25:4-5, 8-9, 10, 14

• 1 Thes 3:12-4:2

• Lk 21:25-28, 34-36

“We preach not one advent only of Christ,” wrote St. Cyril

of Jerusalem in the fourth century, “but a second also, far more glorious than

the former. For the former gave a view of His patience; but the latter brings

with it the crown of a divine kingdom.”

The term “advent,” as we’ll see, is drawn from the New

Testament, but when St. Cyril (named a Doctor of the Church in 1883 by Pope Leo

XIII) was writing his famous catechetical lectures, the season of Advent was

just starting to emerge in fledgling form in Spain and Gaul. During the fifth

century, Christians in parts of western Europe began observing a period of

ascetical practices leading up to the feasts of Christmas and Epiphany. Advent

was observed in Rome beginning in the sixth century, and it was sometimes

called the “pre-Christian Lent,” a time of fasting, more frequent prayer, and

additional liturgies.

One of the prayers of the Roman missal from those early

centuries says, “Stir up our hearts, O Lord, to prepare the ways of Thy

only-begotten Son: that by His coming we may be able to serve him with purified

minds.” This echoes today’s reading from St. Paul’s first letter to the

Christians in Thessalonica, in which he exhorts them “to strengthen your

hearts, to be blameless before our God and Father at the coming of our Lord

Jesus with all his holy ones. Amen.”

The Greek word used by St. Paul for “coming” is parousia, which means “presence” or “coming to a place.” The

Vulgate translation of the phrase “the coming of our Lord Jesus” (1 Thess 3:13)

is rendered “in adventu Domini.”

The word parousia appears

twenty-four times in the New Testament, almost always in reference to the

coming or presence of the Lord. It appears in Matthew 24 four times, the only

place the term appears in the Gospels; that chapter records the Olivet

Discourse, Jesus’ prophetic warnings about a coming time of trial, destruction,

and “the coming of the Son of man” (Matt 24:27). Today’s Gospel reading, from

Luke 21, is a parallel passage warning of distress, startling heavenly signs,

and “the Son of Man coming in a cloud with power and great glory.”

What connection is there between the foment of earthly

tribulation and cosmic upheaval, and preparations to celebrate Christ’s birth?

If we consider the Christmas story cleared of sentimental wrappings, we see

events as dramatic, raw, bloody, and joyous as can be imagined: the birth of

Christ, the slaughter of the innocents, the praise of angels, the murderous

rage of Herod. Christmas is about birth, but also death; about rejoicing, but

also rejection. It is the story of God desired and God denied. It is the story

every man has to encounter because it is the story of God’s radical plan of

salvation, the entrance of divinity into the dusty ruts and twisting corridors

of human history.

Advent orients us to the heart of the Nativity—not in a

merely metaphorical way, but through the reality of the liturgy, the Eucharist,

the sacramental life of the Church. It is a wake-up call, perhaps even an alarm

rousing us from “carousing and drunkenness and the anxieties of daily life.”

The birth of Christ caught many by surprise. Likewise, we can find ourselves

trapped in the darkness of dull living and missing Christ’s call to raise our

heads as salvation approaches.

“Advent calls believers to become aware of this truth and to

act accordingly,” said Pope Benedict XVI in a homily marking the beginning of

Advent in 2006. “It rings out as a salutary appeal in the days, weeks and

months that repeat: Awaken! Remember that God comes! Not yesterday, not

tomorrow, but today, now!” Jesus told his disciples to be vigilant, prepared,

and prayerful.

The same is true for his disciples today, so they might

escape the tribulations of spiritual darkness and stand purified and prepared

before the Son of Man, the son of Mary.

(This "Opening the Word" column appeared originally in the November 29, 2009, issue of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

November 30, 2012

Shaky, Not Stirring

Shaky, Not Stirring | Carl E. Olson | Editorial | Catholic World Report

What happens when Christians put more faith in modernity than they do in the Faith?

Jonathan Aitken, an Anglican, has penned

a piece for The American Spectator praising the edgy, intellectual heights and depths of Rowland Williams

and the late Cardinal Carlo Martini. The latter was not known to many

non-Italian Catholics (at least on this side of the pond), I suspect, until

after he died this past August and it was revealed, with much media furor, that

he was critical of certain qualities exhibited by the Church in Europe. He

stated, rather (in)famously, in an interview late in life, "The Church is

200 years behind the times". This was top-grade catnip for the chattering

classes, who immediately made Cardinal Martini a saint, prophet, and folk hero.

(Russell Shaw ably critiqued the usual suspects in this

September 2012 CWR article.)

Aitken is late to the party, but wants the tired band to

play on. He writes that Cardinal Martini "shook up a heady intellectual

cocktail for the Catholic Church before he passed away." That's certainly

debatable. Making a splash and making a difference are, well, different. And an

occasional fireworks display from the secular media does not equate in the

least to serious—that is, meaningful, mature, and rational—discussion within

the Church. But Aitken seems to think the dusk has fallen on the Catholic

Church; yet a much stronger case can be made that the light of faddish, liberal

Christianity is fast faltering, if only because it is (to switch metaphors in

midstream) parasitical and the host, secular humanism, will only abide it while

it is helpful.

But, before getting too far afield, here is Aitken outlining

the impressive achievements of his two heroes:

The lives of Cardinal Martini and

Archbishop Williams share common themes. Both have held the highest academic

positions and been recognized as great scholars, having produced over 50 works

of theology between them. Both are remarkable linguists—Martini spoke 11

languages and Williams speaks six. Their prelatical concoctions pack a punch,

and both will certainly enliven the debates about the future of the world’s two

largest churches

And, he adds, "Cardinal Carlo Martini, who died on

August 31, was the best modern pope we never had." It's interesting, of

course, to hear what an Anglican hopes for in a pope, keeping in mind that

Anglicanism was the product of a king rejecting the papacy. (If I ever make the

mistake of trumpeting my choice for king or queen of England, please chastise

me promptly.) It appears that Aitken, not surprisingly, would prefer a pope who

is, well, not really Catholic or papal; in short, someone like Williams.

Cardinal Martini, he notes approvingly, "was the

counterweight to papal conservatism. On a crucial range of

issues—contraception, homosexuality, family values, and the right to end

life—he took popular positions that made him almost a leader of the opposition

within the hierarchy of the church." Or, in other words, he apparently

took positions contrary to historical, traditional Catholic teaching.

Agreed—those positions are certainly popular, most notably among those who have

either renounced the Catholic Faith or large chunks of it. Shocking, that.

Anyhow, this means Martini is deemed worthy of one of the greatest titles that

can be granted a capitulating Christian: modernizer. The assumption is that being

"modern"—which seems to ultimately fixate on loosening moral and

marital bonds while lamenting the demands of traditional beliefs—is not just

inevitable but enviable.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers