Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 159

April 2, 2013

Knights for Peace and Sanctification in the Middle East

Knights for Peace and Sanctification in the Middle East | William L. Patenaude | Catholic World Report

The Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem works to support the people and shrines of the Holy Land.

Almost a thousand years after its founding, an order of crusader knights remains active in the Holy Land. Its mission is not armed battle but the carrying out of the order’s original ideals: personal holiness, evangelization, defense of the weak, and charity towards all. Its members also pledge to support the upkeep of the shrines where Christ was born, prayed, mounted his cross, and rose from the dead.

Founded soon after the First Crusade, the pontifical Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem currently has some 28,000 clerical, religious, and lay members across the globe. While the order’s titles, regalia, and ceremonies of investiture come with great honor and dignity (and a rigorous nomination process), membership comes with a lifetime pledge of spiritual and worldly support for the Holy Land. As a result, the order offers countless prayers and millions of dollars annually to build, operate, maintain, and expand schools, youth centers, hospitals, seminaries, homes for religious, pre- and post-natal clinics, and the only Catholic institution of higher education in Israel, Bethlehem University.

“Our primary aim is personal sanctification,” stresses Cardinal Edwin O’Brien, Grand Master of the worldwide order. “I am convinced that with this focus on holiness, the charism [to support the people and shrines of the Holy Land] comes into full bloom.”

The charitable order grew out of the need to govern Jerusalem after Godfrey de Bouillon and his crusaders freed the city from Muslim control in July 1099. The resulting “Order of Canons” included knights who had exhibited noticeable leadership skills and Christian charity. These soldiers-turned-protectors would take the Augustinian Rule of poverty and obedience and swear to defend the Holy Sepulchre (the site of Christ’s resurrection) and other Christian shrines.

Over time, many of the knights returned to Europe and Muslim armies retook Jerusalem. But with the aid of political and ecclesial encouragement, the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem founded priories throughout Europe that kept alive its original oaths and charitable goals. With the restoration of Jerusalem’s Latin Patriarchate in 1847, Pope Pius IX placed the order under the full protection of the Holy See. A century later, Pius XII ordered that a prince of the Church would hold the role of the order’s Grand Master. Subsequent pontiffs brought even more structure.

What has not changed, however, is the order’s commitment to the Bishop of Rome and to Jerusalem’s Latin Patriarch. The order thus serves as a bridge between the Church in the West and the people in the Middle East—especially Christians, who often find themselves caught in the midst of the regional political, social, and economic difficulties.

“The Christian minority living in the Holy Land increasingly faces the challenge of practicing their faith in the midst of conflict and turmoil,” said Cardinal Sean O’Malley, OFM, Cap., archbishop of Boston and Grand Prior of the order’s Northeast United States Lieutenancy.

April 1, 2013

New: "On Heaven and Earth" by Jorge Mario Bergoglio (Pope Francis)

Available on April 30, 2013 from Ignatius Press: On Heaven and Earth: Pope Francis on Faith, Family, and the Church in the Twenty-First Century

On Heaven and Earth: Pope Francis on Faith, Family, and the Church in the Twenty-First Century

by Jorge Mario Bergoglio and Abraham Skorka

224 pp | Hardcover

From the man who became Pope Francis--Jorge Mario Bergoglio shares his thoughts on religion, reason, and the challenges the world faces in the 21st century with Abraham Skorka, a rabbi and biophysicist.

For years Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, archbishop of Argentina, and Rabbi Abraham Skorka were tenacious promoters of interreligious dialogues on faith and reason. They both sought to build bridges among Catholicism, Judaism, and the world at large. On Heaven and Earth, originally published in Argentina in 2010, brings together a series of these conversations where both men talked about various theological and worldly issues, including God, fundamentalism, atheism, abortion, homosexuality, euthanasia, same-sex marriage, and globalization.

From these personal and accessible talks comes a first-hand view of the man who would become pope to 1.2 billion Catholics around the world in March 2013.

"See How the Church Is Alive Today!"

"See How the Church Is Alive Today!" | Paul Erich Menge | CWR blog

The last forty years have witnessed a flowering of faith in the Church, despite numerous challenges and difficulties

"But we see how the Church is alive today!" — Benedict XVI, Final General Audience, Feb. 27, 2013.

Upheaval

in the Church and confusion among the faithful. The late 1960s and early 1970s were dark days indeed, as

reported by Kenneth L. Woodward in his memoir of big changes to the Church in

the wake of the Second Vatican Council, in the February 2013

issue of the journal First Things.

Woodward at that time was religion editor at Newsweek magazine.

But

Woodward’s account takes us only into 1971. It is only the beginning of the story. Then, gradually, came a flowering, the

evidentiary work of the Holy Spirit, a great happening, a turn in salvation

history.

First

stirrings were the emergence of the Catholic Charismatic Renewal in February

1967 with its appreciation for the work of the Holy Spirit, which spread

throughout the Church; publication in 1971 of Malcolm Muggeridge’s Something

Beautiful for God,

which brought to the public’s attention the ministry of Mother Teresa of

Calcutta and her Missionaries of Charity; founding of the international journal

Communio

in 1972 by Joseph Ratzinger and other prominent theologians who in 1970 broke

with the progressive journal Concilium; the Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision

in January 1973 which prompted into existence the anti-abortion/pro-life

movement; appointment of Fr. Michael Scanlan in 1974 to be president of the

College of Steubenville and to begin the rescue and spiritual transformation of

the college (re-named Franciscan University of Steubenville in 1985); and the

“Hartford Appeal for Theological Affirmation” of February 1975, which was a

response of fourteen Christian thinkers to current distortions of Christian

faith, “the casual jettisoning of Christian orthodoxy,” and included

identification of thirteen “false and debilitating” theses.

Multiple

fruits of the Spirit appeared in the late 1970s and early 1980s, most notably

the papacy of Bl. John Paul II, beginning in 1978 and continuing for 27 years.

Vatican II and the “Bad News” of the Gospel

Vatican II and the “Bad News” of the Gospel | David Paul Deavel | Catholic World Report

Ralph Martin’s new book clarifies what the Council actually taught about salvation outside the Church.

Ruefully observing statistics

showing that only 6 percent of American Catholic parishes considered evangelism

a priority, the late Cardinal Avery Dulles once lamented, “The Council has

often been interpreted as if it had discouraged evangelization.” Ralph Martin’s new book, Will Many Be

Saved? What Vatican II Actually Teaches

and Its Implications for the New Evangelization, aims to explain why this

interpretation has taken root despite the fact that the Council documents,

particularly the keystone document Lumen Gentium (LG), are brimming with

talk about evangelization as the Church’s main job. In fact, Paul VI’s

encyclical Evangelii Nuntiandi stated that the objectives of the Council

were summed up in one statement: “to

make the Church of the 20th century ever better fitted for proclaiming the

Gospel.” Yet the opposite happened.

Martin thinks, and with reason,

that the loss of impetus to evangelize is based upon the widespread notion

after the Council that almost everybody will be saved—except maybe really evil

people like Hitler and Judas. Having the sacraments or an explicit faith in

Christ is seen as a nice add-on. But essentially the theology of salvation

could be summed up by the 1989 cartoon movie All Dogs Go to Heaven.

Of course this theology had

backing from big names. Karl Rahner declared that the Council had a

“theological optimism…concerning salvation.” Richard McBrien’s commentary on LG

claimed that the Church now considered the human race as “an essentially saved

community from whom a few may, by the exercise of their own free will, be

lost.” Even the Jesuit scholar Francis Sullivan, author of a very careful study

of the teaching on salvation outside the Church, tended in his more popular

writings to throw caution to the wind and claim a “general presumption of

innocence which is now the official attitude of the Catholic Church.” These

claims were never undergirded by any actual citations or close readings from

the Council, which marked a doctrinal development indeed, but not one of

automatic salvation or “presumed innocence.”

While the question of the

salvation of those who have never heard the Gospel has been bubbling up in a

new way since the 16th-century discovery of peoples in the New World, it had

been coming to a steady boil over more than 100 years before Vatican II.

March 31, 2013

"The Truth of the Resurrection" by Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

The Truth of the Resurrection | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger | From

Introduction to Christianity

To the Christian, faith in the Resurrection of Jesus Christ is an expression of certainty that

the saying that seems to be only a beautiful dream is in fact true: "Love

is strong as death" (Song 8:6). In the Old Testament this sentence comes

in the middle of praises of the power of eros. But this by no means signifies that we can simply

push it aside as a lyrical exaggeration. The boundless demands of eros", its apparent exaggerations and extravagance, do in

reality give expression to a basic problem, indeed the" basic problem of human existence, insofar as they

reflect the nature and intrinsic paradox of love: love demands infinity,

indestructibility; indeed, it is, so to speak, a call for infinity. But it is

also a fact that this cry of love's cannot be satisfied, that it demands

infinity but cannot grant it; that it claims eternity but in fact is included

in the world of death, in its loneliness and its power of destruction. Only

from this angle can one understand what "resurrection" means. It is" the greater strength of love in face of death.

At the same time it is proof of what only immortality can create: being in the

other who still stands when I have fallen apart. Man is a being who himself

does not live forever but is necessarily delivered up to death. For him, since

he has no continuance in himself, survival, from a purely human point of view,

can only become possible through his continuing to exist in another. The

statements of Scripture about the connection between sin and death are to he

understood from this angle. For it now becomes clear that man's attempt

"to be like God", his striving for autonomy, through which he wishes

to stand on his own feet alone, means his death, for he just cannot stand on

his own. If man--and this is the real nature of sin--nevertheless refuses to

recognize his own limits and tries to be completely self-sufficient, then

precisely by adopting this attitude he delivers himself up to death.

Of course man does understand that his life alone does not endure and that he

must therefore strive to exist in others, so as to remain through them and in

them in the land of the living. Two ways in particular have been tried. First,

living on in one's own children: that is why in primitive peoples failure to

marry and childlessness are regarded as the most terrible curse; they mean

hopeless destruction, final death. Conversely, the largest possible number of

children offers at the same time the greatest possible chance of survival, hope

of immortality, and thus the most genuine blessing that man can expect. Another

way discloses itself when man discovers that in his children he only continues

to exist in a very unreal way; he wants more of himself to remain. So he takes

refuge in the idea of fame, which should make him really immortal if be lives

on through all ages in the memory of others. But this second attempt of man's

to obtain immortality for himself by existing in others fails just as badly as

the first: what remains is not the self but only its echo, a mere shadow. So

self-made immortality is really only a Hades, a sheol": more nonbeing than being. The inadequacy of both ways

lies partly in the fact that the other person who holds my being after my death

cannot carry this being itself but only its echo; and even more in the fact

that even time other person to whom I have, so to speak, entrusted my

continuance will not last--he, too, will perish.

This leads us to the next step. We have seen so far that man has no permanence

in himself. And consequently can only continue to exist in another but that his

existence in another is only shadowy and once again not final, because this

other must perish, too. If this is so, then only one could truly give lasting

stability: he who is, who does not come into existence and pass away again but

abides in the midst of transience: the God of the living, who does not hold

just the shadow and echo of my being, whose ideas are not just copies of

reality. I myself am his thought, which establishes me more securely, so to

speak, than I am in myself; his thought is not the posthumous shadow but the

original source and strength of my being. In him I can stand as more than a shadow;

in him I am truly closer to myself than I should be if I just tried to stay by

myself.

Before we return from here to the Resurrection, let us try to see the same

thing once again from a somewhat different side. We can start again from the

dictum about love and death and say: Only where someone values love more highly

than life, that is, only where someone is ready to put life second to love, for

the sake of love, can love be stronger and more than death. If it is to be more

than death, it must first be more than mere life. But if it could be this, not

just in intention but in reality, then that would mean at the same time that

the power of love had risen superior to the power of the merely biological and

taken it into its service. To use Teilhard de Chardin's terminology; where that

took place, the decisive complexity or "complexification" would have occurred;

bios, too, would be encompassed

by and incorporated in the power of love. It would cross the boundary--death--and

create unity where death divides. If the power of love for another were so

strong somewhere that it could keep alive not just his memory, the shadow of

his "I", but that person himself, then a new stage in life would have

been reached. This would mean that the realm of biological evolutions and

mutations had been left behind and the leap made to a quite different plane, on

which love was no longer subject to bios but made use of it. Such a final stage of "mutation" and

"evolution" would itself no longer be a biological stage; it would

signify the end of the sovereignty of bios, which is at the same time the sovereignty of death; it would open up

the realm that the Greek Bible calls zoe, that is, definitive life, which has left behind the rule of death.

The last stage of evolution needed by the world to reach its goal would then no

longer be achieved within the realm of biology but by the spirit, by freedom,

by love. It would no longer be evolution but decision and gift in one.

But what has all this to do, it may be asked, with faith in the Resurrection of

Jesus? Well, we previously considered the question of the possible immortality

of man from two sides, which now turn out to be aspects of one and. the same state

of affairs. We said that, as man has no permanence in himself, his survival

could. only be brought about by his living on in another. And we said, from the

point of view of this "other", that only the love that takes up the

beloved in itself, into its own being, could make possible this existence in

the other. These two complementary aspects are mirrored again, so it seems to

me, in the two New Testament ways of describing the Resurrection of the Lord:

"Jesus has risen" and "God (the Father) has awakened

Jesus." The two formulas meet in the fact that Jesus' total love for men,

which leads him to the Cross, is perfected in totally passing beyond to the

Father and therein becomes stronger than death, because in this it is at the

same time total "being held" by him.

From this a further step results. We can now say that love always establishes

some kind of immortality; even in its prehuman stage, it points, in the form of

preservation of the species, in this direction. Indeed, this founding of

immortality is not something incidental to love, not one thing that it does

among others, but what really gives it its specific character. This principle

can be reversed; it then signifies that immortality always" proceeds from love, never out of the autarchy of

that which is sufficient to itself. We may even be bold enough to assert that

this principle, properly understood, also applies even to God as he is seen by

the Christian faith. God, too, is absolute permanence, as opposed to everything

transitory, for the reason that he is the relation of three Persons to one

another, their incorporation in the "for one another" of love,

act-substance of the love that is absolute and therefore completely

"relative", living only "in relation to". As we said

earlier, it is not autarchy, which knows no one but itself, that is divine;

what is revolutionary about the Christian view of the world and of God, we

found, as opposed to those of antiquity, is that it learns to understand the

"absolute" as absolute "relatedness", as relatio

subsistens.

To return to our argument, love is the foundation of immortality, and

immortality proceeds from love alone. This statement to which we have now

worked our way also means that he who has love for all has established

immortality for all. That is precisely the meaning of the biblical statement that

his Resurrection is our life.

The--to us--curious reasoning of St. Paul in his First Letter to the

Corinthians now becomes comprehensible: if he has risen, then we have, too, for

then love is stronger than death; if he has not risen, then we have not either,

for then the situation is still that death has the last word, nothing else (cf.

I Cor 15:16f.). Since this is a statement of central importance, let us spell

it out once again in a different way: Either love is stronger than death, or it

is not. If it has become so in him, then it became so precisely as love for

others. This also means, it is true, that our own love, left to itself, is not

sufficient to overcome death; taken in itself it would have to remain an

unanswered cry. It means that only his love, coinciding with God's own power of

life and love, can be the foundation of our immortality. Nevertheless, it still

remains true that the mode of our immortality will depend on our mode of

loving. We shall have to return to this in the section on the Last Judgment.

A further point emerges from this discussion. Given the foregoing

considerations, it goes without saying that the life of him who has risen from

the dead is not once again bios, the biological form of our mortal life within

history; it is zoe, new,

different, definitive life; life that has stepped beyond the mortal realm of

bios and history, a realm that has here been surpassed by a greater power. And

in fact the Resurrection narratives of the New Testament allow us to see

clearly that the life of the Risen One lies, not within the historical bios,

but beyond and above it. It is also true, of course, that this new life begot

itself in history and had to do so, because after all it is there for history,

and the Christian message is basically nothing else than the transmission of

the testimony that love has managed to break through death here and thus has

transformed fundamentally the situation of all of us. Once we have realized

this, it is no longer difficult to find the right kind of hermeneutics for the

difficult business of expounding the biblical Resurrection narratives, that is,

to acquire a clear understanding of the sense in which they must properly be

understood. Obviously we cannot attempt here a detailed discussion of the

questions involved, which today present themselves in a more difficult form

than ever before; especially as historical and--for the most part inadequately pondered--philosophical

statements are becoming more and more inextricably intertwined, and exegesis

itself quite often produces its own philosophy, which is intended to appear to the

layman as a supremely refined distillation of the biblical evidence. Many

points of detail will here always remain open to discussion, but it is possible

to recognize a fundamental dividing line between explanation that remains

explanation and arbitrary adaptations [to contemporary ways of thinking].

First of all, it is quite clear that after his Resurrection Christ did not go

back to his previous earthly life, as we are told the young man of Nain and

Lazarus did. He rose again to definitive life, which is no longer governed by

chemical and biological laws and therefore stands outside the possibility of

death, in the eternity conferred by love. That is why the encounters with him

are "appearances"; that is why he with whom people had sat at table

two days earlier is not recognized by his best friends and, even when

recognized, remains foreign: only where he grants vision is he

seen; only when he opens men's eyes and makes their hearts open up can the countenance

of the eternal love that conquers death become recognizable in our mortal

world, and, in that love, the new, different world, the world of him who is to

come. That is also why it is so difficult, indeed absolutely impossible, for the

Gospels to describe the encounter with the risen Christ; that is why they can

only stammer when they speak of these meetings and seem to provide

contradictory descriptions of them. In reality they are surprisingly unanimous

in the dialectic of their statements, in the simultaneity of touching and not

touching, or recognizing and not recognizing, of complete identity between the

crucified and the risen Christ and complete transformation. People recognize

the Lord and yet do not recognize him again; people touch him, and yet he is untouchable;

he is the same and yet quite different. As we have said, the dialectic is always

the same; it is only the stylistic means by which it is expressed that changes.

For example, let us examine a little more closely from this point of view the

Emmaus story, which we have already touched upon briefly. At first sight it

looks as if we are confronted here with a completely earthly and material

notion of resurrection; as if nothing remains of the mysterious and indescribable

elements to be found in the Pauline accounts. It looks as if the tendency to

detailed depiction, to the concreteness of legend, supported by the apologist's

desire for something tangible, had completely won the upper hand and fetched

the risen Lord right back into earthly history. But this impression is soon

contradicted by his mysterious appearance and his no less mysterious

disappearance. The notion is contradicted even more by the fact that here, too,

he remains unrecognizable to the accustomed eye. He cannot be firmly grasped as

he could be in the time of his earthly life; he is discovered only in the realm

of faith; he sets the hearts of the two travelers aflame by his interpretation

of the Scriptures and by breaking bread he opens their eyes. This is a

reference to the two basic elements in early Christian worship, which consisted

of the liturgy of the word (the reading and expounding of Scripture) and the

eucharistic breaking of bread. In this way the evangelist makes it clear that

the encounter with the risen Christ lies on a quite new plane; he tries to describe

the indescribable in terms of the liturgical facts. He thereby provides both a

theology of the Resurrection and a theology of the liturgy: one encounters the risen

Christ in the word and in the sacrament; worship is the way in which he becomes

touchable to us and, recognizable as the living Christ. And conversely, the

liturgy is based on the mystery of Easter; it is to he understood as the Lords approach

to us. In it he becomes our traveling companion, sets our dull hearts aflame,

and opens our sealed eyes. He still walks with us, still finds us worried and

downhearted, and still has the power to make us see.

Of course, all this is only half the story; to stop at this alone would mean

falsifying the evidence of the New Testament. Experience of the risen Christ is

something other than a meeting with a man from within our history, and it must certainly

not be traced back to conversations at table and recollections that would have

finally crystallized in the idea that he still lived and went about his business.

Such an interpretation reduces what happened to the purely human level and robs

it of its specific quality. The Resurrection narratives are something other and

more than disguised liturgical scenes: they make visible the founding event on

which all Christian liturgy rests. They testify to an approach that did not

rise from the hearts of the disciples but came to them from outside, convinced

them despite their doubts and

made them certain that the Lord had truly risen. He who lay in the grave is no longer

there; he--really he himself--lives. He who had been transposed into the other

world of God showed himself powerful enough to make it palpably clear that he

himself stood in their presence again, that in him the power of love had really

proved itself stronger than the power of death.

Only by taking this just as seriously as what we said first does one remain

faithful to the witness borne by the New Testament; only thus, too, is its

seriousness in world history preserved. The comfortable attempt to spare

oneself the belief in the mystery of God's mighty actions in this world and yet

at the same time to have the satisfaction of remaining on the foundation of the

biblical message leads nowhere; it measures up neither to the honesty of reason

nor to the claims of faith. One cannot have both the Christian faith and

"religion within the bounds of pure reason"; a choice is unavoidable.

He who believes will see more and more clearly, it is true, how rational it is

to have faith in the love that has conquered death.

The Logic of the Resurrection

The Logic of the Resurrection | Fr. James V. Schall, SJ | Catholic World Report

The truth of the resurrection of the body is bound up with the question of justice.

The

resurrection of the body is not primarily a question of logic. It is a question

of fact, of witness. We do not begin from a philosophical theory to deduce the

resurrection of the body. Rather we start from the fact of the resurrection of

Christ. We ask whether it makes sense, whether it is “reasonable” in some basic

manner. In this sense, philosophy follows fact, provided we can accept the

facts of what is.

In his

book, Jesus

of Nazareth: Holy Week, Benedict XVI examined all the evidence that would argue

that the resurrection as a fact did not happen. He concluded we have no evidence

showing that the testimony and witness of the disciples present at the events

were fabricated, false, or naïve. We conclude that Jesus was who He said He

was. Included in this understanding of who He was is His resurrection. But the

resurrection involves the fact that Christ as such was one of the Persons of

the Trinity, the Word, who became man. It was not the Father or the Spirit who

became man. The resurrection thus refers to Christ insofar as He was true man,

yet also God.

We learn

in the Old Testament that God never intended for us to die. But we also learn

that death was a consequence of a prior act of man. Death followed the exercise

of freedom. Man was not forced to be what he was intended to be. We might then

expect that the overcoming of death would also be the consequence of freedom.

The question is whether the exercise of human freedom, our self-redemption, was

sufficient to accomplish this purpose. The whole account of Christ’s passion

revolves about this issue.

Behind

this question of freedom, however, is the fact that by nature we human beings,

body and soul, are not free from death. We are the mortals. We die and we know

that we die. Yet, something about us seems “immortal.” We call our souls

precisely immortal, a spiritual power. But this immortality as such does not

include our bodies, the whole persons that we are.

March 30, 2013

"They Killed Him": Deicide and Holy Saturday

"They Killed Him": Deicide and Holy Saturday | Dr. Leroy Huizenga | Catholic World Report

The Christ is dead; the corpse of

the Son of God lies on a cold slab in a suffocating, lightless tomb.

Holy Saturday is a difficult day to

keep holy. My parish marks it with morning prayer from the Liturgy of the

Hours, but most churches don’t do anything, which is certainly appropriate;

Jesus Christ is liturgically dead. And so I’ve taken to my own observances.

Last year after the Good Friday communion liturgy, my wife and I watched The

Passion of the Christ, and on Holy Saturday we kept things low-key while

listening to Bach’s Matthäus-Passion and Johannes-Passion as well as Mozart’s

and Verdi’s Requiems.

But life goes on. Our young kids

(almost 5 and 3) can’t help but play, sometimes cooperating, sometimes

protesting in shrill tones some grave injustice the other has perpetrated by

encroaching on (say) a Thomas the Tank Engine track layout. My mother will host

Easter dinner, and so we will prepare some food for that. And for many people,

even those who will be in Easter Sunday services tomorrow, Holy Saturday is

another Saturday filled with shopping, yardwork, fishing, and the like.

Holy Saturday started to hit me

differently a few years ago. I suspect it had to do with three major events

occurring within a period of several months. First, I turned 35, which meant my

life was half over, as I’d count myself blessed to make it to seventy. I began

to feel life was now downhill. Second, our son Hans was born, and as those of

you who are parents know, having children entails epistemological paradigm

shifts: we see the world differently. Third, just a few weeks after Hans’

birth, I buried my father. And so I came to the existential realization that

life was short and moving ever faster and that we play for keeps.

Sensitive now to the fragility of

human life and the grave responsibilities laid upon us by God and Nature and

newly alive to the joys and terrors of life in this beautiful and horrible

world as a member of a glorious and murderous race, Holy Saturday punched me in

the gut.

They killed him. They really did.

Many Christians in modernity, I

think, have a conception of the crucifixion restricted to a legal version of

penal substitutionary atonement: Our problem is guilt, for which God must

punish us, but loving us and desiring to forgive us, God punishes Christ in our

place.

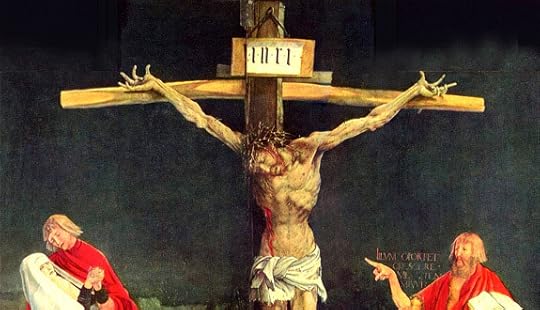

The Cross, For Us

The Cross, For Us | Hans Urs von Balthasar

Whoever removes the Cross from the center of Christianity no longer stands in continuity with the apostolic faith

The following is from A Short Primer for Unsettled Laymen (Ignatius Press, 1985).

Without a doubt, at the center of the New Testament there stands the Cross,

which receives its interpretation from the Resurrection.

The Passion narratives are the first pieces of the Gospels that were composed

as a unity. In his preaching at Corinth, Paul initially wants to know

nothing but the Cross, which "destroys the wisdom of the wise and wrecks

the understanding of those who understand", which "is a scandal to the

Jews and foolishness to the gentiles". But "the foolishness of God is

wiser than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men" (1 Cor 1:19,

23, 25).

Whoever removes the Cross and its interpretation

by the New Testament from the center, in order to replace it, for example,

with the social commitment of Jesus to the oppressed as a new center,

no longer stands in continuity with the apostolic faith. He does not see

that God's commitment to the world is most absolute precisely at this

point across a chasm.

It is certainly not surprising that the disciples were able to understand

the meaning of the Cross only slowly, even after the Resurrection. The

Lord himself gives a first catechetical instruction to the disciples at

Emmaus by showing that this incomprehensible event is the fulfillment

of what had been foretold and that the open question marks of the Old

Testament find their solution only here (Lk 24:27).

Which riddles? Those of the Covenant between God

and men in which the latter must necessarily fail again and again: who

can be a match for God as a partner? Those of the many cultic sacrifices

that in the end are still external to man while he himself cannot offer

himself as a sacrifice. Those of the inscrutable meaning of suffering

which can fall even, and especially, on the innocent, so that every proof

that God rewards the good becomes void. Only at the outer periphery, as

something that so far is completely sealed, appear the outlines of a figure

in which the riddles might be solved.

This figure would be at once the completely kept

and fulfilled Covenant, even far beyond Israel (Is 49:5-6), and the personified

sacrifice in which at the same time the riddle of suffering, of being

despised and rejected, becomes a light; for it happens as the vicarious

suffering of the just for "the many" (Is 52:13-53:12). Nobody had understood

the prophecy then, but in the light of the Cross and Resurrection of Jesus

it became the most important key to the meaning of the apparently meaningless.

Did not Jesus himself use this key at the Last Supper in anticipation?

"For you", "for the many", his Body is given up and his Blood is poured

out. He himself, without a doubt, foreknew that his will to help these"

people toward God who are so distant from God would at some point be taken

terribly seriously, that he would suffer in their place through this distance

from God, indeed this utmost darkness of God, in order to take it from

them and to give them an inner share in his closeness to God. "I have

a baptism to be baptized with, and how I am constrained until it is accomplished!"

(Lk 12:50).

It stands as a dark cloud at the horizon of his active life; everything

he does then-healing the sick, proclaiming the kingdom of God, driving

out evil spirits by his good Spirit, forgiving sins-all of these partial

engagements happen in the approach toward the one unconditional engagement.

As soon as the formula "for the many", "for you", "for us", is found,

it resounds through all the writings of the New Testament; it is even

present before anything is written down (cf. i Cor 15:3). Paul, Peter,

John: everywhere the same light comes from the two little words.

What has happened? Light has for the first time penetrated into the closed

dungeons of human and cosmic suffering and dying. Pain and death receive

meaning.

Not only that, they can receive more meaning and

bear more fruit than the greatest and most successful activity, a meaning

not only for the one who suffers but precisely also for others, for the

world as a whole. No religion had even approached this thought. [1] The

great religions had mostly been ingenious methods of escaping suffering

or of making it ineffective. The highest that was reached was voluntary

death for the sake of justice: Socrates and his spiritualized heroism.

The detached farewell discourses of the wise man in prison could be compared

from afar to the wondrous farewell discourses of Christ.

But Socrates dies noble and transfigured; Christ

must go out into the hellish darkness of godforsakenness, where he calls

for the lost Father "with prayers and supplications, with loud cries and

tears" (Heb 5:7). Why are such stories handed down? Why has the image

of the hero, the martyr, thus been destroyed? It was "for us", "in our

place".

One can ask endlessly how it is possible to take someone's place in this

way. The only thing that helps us who are perplexed is the certainty of

the original Church that this man belongs to God, that "he truly was God's

Son", as the centurion acknowledges under the Cross, so that finally one

has to render him homage in adoration as "my Lord and my God" Jn 20:28).

Every theology that begins to blink and stutter at this point and does

not want to come out with the words of the Apostle Thomas or tinkers with

them will not hold to the "for us". There is no intermediary between a

man who is God and an ordinary mortal, and nobody will seriously hold

the opinion that a man like us, be he ever so courageous and generous

in giving himself, would be able to take upon himself the sin of another,

let alone the sin of all. He can suffer death in the place of someone

who is condemned to death. This would be generous, and it would spare

the other person death at least for a time.

But what Christ did on the Cross was in no way intended to spare us death

but rather to revalue death completely. In place of the "going down into

the pit" of the Old Testament, it became "being in paradise tomorrow".

Instead of fearing death as the final evil and begging God for a few more

years of life, as the weeping king Hezekiah does, Paul would like most

of all to die immediately in order "to be with the Lord" (Phil 1:23).

Together with death, life is also revalued: "If we live, we live to the

Lord; if we die, we die to the Lord" (Rom 14:8).

But the issue is not only life and death but our existence before God

and our being judged by him. All of us were sinners before him and worthy

of condemnation. But God "made the One who knew no sin to be sin, so that

we might be justified through him in God's eyes" (2 Cor 5:21).

Only God in his absolute freedom can take hold of our finite freedom from

within in such a way as to give it a direction toward him, an exit to

him, when it was closed in on itself. This happened in virtue of the "wonderful

exchange" between Christ and us: he experiences instead of us what distance

from God is, so that we may become beloved and loving children of God

instead of being his "enemies" (Rom 5:10).

Certainly God has the initiative in this reconciliation: he is the one

who reconciles the world to himself in Christ. But one must not play this

down (as famous theologians do) by saying that God is always the reconciled

God anyway and merely manifests this state in a final way through the

death of Christ. It is not clear how this could be the fitting and humanly

intelligible form of such a manifestation.

No, the "wonderful exchange" on the Cross is the way by which God brings

about reconciliation. It can only be a mutual reconciliation because God

has long since been in a covenant with us. The mere forgiveness of God

would not affect us in our alienation from God. Man must be represented

in the making of the new treaty of peace, the "new and eternal covenant".

He is represented because we have been taken over by the man Jesus Christ.

When he "signs" this treaty in advance in the name of all of us, it suffices

if we add our name under his now or, at the latest, when we die.

Of course, it would be meaningless to speak of the Cross without considering

the other side, the Resurrection of the Crucified. "If Christ has not

risen, then our preaching is nothing and also your faith is nothing; you

are still in your sins and also those who have fallen asleep . . . are

lost. If we are merely people who have put their whole hope in Christ

in this life, then we are the most pitiful of all men" (1 Cor 15:14, 17-19).

If one does away with the fact of the Resurrection, one also does away

with the Cross, for both stand and fall together, and one would then have

to find a new center for the whole message of the gospel. What would come

to occupy this center is at best a mild father-god who is not affected

by the terrible injustice in the world, or man in his morality and hope

who must take care of his own redemption: "atheism in Christianity".

Endnotes:

[1] For what is meant here is something qualitatively completely different

from the voluntary or involuntary scapegoats who offered themselves or

were offered (e.g., in Hellas or Rome) for the city or for the fatherland

to avert some catastrophe that threatened everyone.

March 28, 2013

The Violence of the Crucifixion

The Violence of the Crucifixion | Dr. Leroy

Huizenga | Catholic World Report

The Four Evangelists glory not in the cross’ gore but rather in its shame

One of my

duties at the University of Mary in Bismarck, ND, where I chair the Theology

Department, is to help our student music leaders select music appropriate for

our well-attended masses. For a recent Wednesday in Lent, for offertory and

communion the students selected “O Sacred Head Surrounded,” familiar to many,

as well as “Glory Be to Jesus,” an eighteenth-century Italian hymn translated

into English in the nineteenth.

The hymn we

know as “O Sacred Head Surrounded” originated in Latin in the middle ages. The

famous tune and words appear in the Passion Chorale in Bach’s St. Matthew

Passion. German often sounds blunt to English ears, and the rendering of O

Haupt voll Blut und Wunden / Voll Schmerz und voller Hohn in the English hymn is as brutal as the German: O

Sacred Head surrounded / by crown

of piercing thorn! / O bleeding head, so wounded / reviled and put to

scorn! The second stanza likewise speaks of death with cruel rigor and agony and dying. “Glory Be to Jesus” is similar, especially in the

first stanza: Glory Be to Jesus / Who in bitter pains / Poured for me

the lifeblood / from his sacred veins.

Having

reviewed the lineup for the mass before the worship aid was to go to print, a

member of our campus ministry team sent an email in which she wondered if the

repeated references to Jesus’ corporal suffering weren’t a bit much, especially

when presented in such a blunt and baroque fashion. My first thought was that

it was deep into Lent, and so some lyrical reminders of the depths of the

suffering of Christ were entirely appropriate. But our first reactions are not

always right, and while we kept the hymns in place, in thinking about it I came

to see my colleague had made a good point.

The hymns themselves

are wonderful in tune and lyric; there’s nothing essentially wrong with them.

But my friend’s instincts were good, for too often Christians focus on the gore

involved in the torture and crucifixion of our Lord and miss out on the deeper

violence of the crucifixion, the violence on which ancient writers and the

Evangelists themselves concentrate.

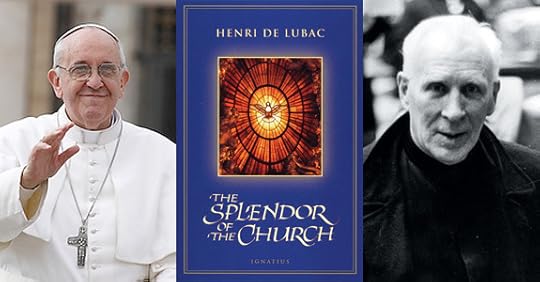

Pope Francis and Henri de Lubac, SJ

Pope Francis and Henri de Lubac, SJ | Carl E. Olson | CWR blog

Sandro Magister reports:

It is a widespread opinion, confirmed by numerous testimonies, that the

intention of electing pope Jorge Mario Bergoglio grew substantially

among the cardinals on the morning of Saturday, March 9, when the

then-archbishop of Buenos Aires spoke at the second to last of the

congregations - covered by secrecy - that preceded the conclave.

His

words made an impression on many. Bergoglio spoke off the cuff. But we

now have the account of those words of his, written by the hand of the

author himself.

Bergoglio's remarks in the preconclave were made

public by the cardinal of Havana, Jaime Lucas Ortega y Alamino, in the

homily of the chrism Mass that he celebrated on Saturday, March 23 in

the cathedral of the capital of Cuba, in the presence of the apostolic

nuncio, Archbishop Bruno Musarò, of the auxiliary bishops Alfredo Petit

and Juan de Dios Hernandez, and of the clergy of the diocese.

Cardinal

Ortega recounted that after the remarks of Bergoglio in the

preconclave, he had approached him to ask if he had a written text that

he could keep.

Bergoglio responded that at the moment he did not

have one. But the following day - Ortega recounted - "with extreme

delicacy” he gave him “the remarks written in his own hand as he

recalled them."

Ortega asked him if he could release the text, and Bergoglio said yes.

Here is that text of Cardinal Bergoglio's notes:

Reference has been made to evangelization. This is the Church's reason

for being. “The sweet and comforting joy of evangelizing” (Paul VI). It

is Jesus Christ himself who, from within, impels us.

1)

Evangelizing implies apostolic zeal. Evangelizing presupposes in the

Church the “parresia" of coming out from itself. The Church is called to

come out from itself and to go to the peripheries, not only

geographical, but also existential: those of the mystery of sin, of

suffering, of injustice, those of ignorance and of the absence of faith,

those of thought, those of every form of misery.

2) When the

Church does not come out from itself to evangelize it becomes

self-referential and gets sick (one thinks of the woman hunched over

upon herself in the Gospel). The evils that, in the passing of time,

afflict the ecclesiastical institutions have a root in

self-referentiality, in a sort of theological narcissism. In Revelation,

Jesus says that he is standing at the threshold and calling. Evidently

the text refers to the fact that he stands outside the door and knocks

to enter. . . But at times I think that Jesus may be knocking from the

inside, that we may let him out. The self-referential Church presumes to

keep Jesus Christ within itself and not let him out.

3) The

Church, when it is self-referential, without realizing it thinks that it

has its own light; it stops being the “mysterium lunae" and gives rise

to that evil which is so grave, that of spiritual worldliness (according

to De Lubac, the worst evil into which the Church can fall): that of

living to give glory to one another. To simplify, there are two images

of the Church: the evangelizing Church that goes out from itself; that

of the “Dei Verbum religiose audiens et fidenter proclamans" [the Church

that devoutly listens to and faithfully proclaims the Word of God -

editor's note], or the worldly Church that lives in itself, of itself,

for itself. This should illuminate the possible changes and reforms to

be realized for the salvation of souls.

4) Thinking of the next

Pope: a man who, through the contemplation of Jesus Christ and the

adoration of Jesus Christ, may help the Church to go out from itself

toward the existential peripheries, that may help it to be the fecund

mother who lives “by the sweet and comforting joy of evangelizing.”

Rome, March 9, 2013

The influence of de Lubac, one of the finest Jesuit theologians of the past century, on Bergoglio is also obvious in this 2007 interview, which ends with this remark:

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers