Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 131

September 17, 2013

The Feast of Two Remarkable Doctors

Today is the Feast of two Doctors of the Church, a man and a woman who are remarkable in many ways, including in how very different they are from one another.

First, St. Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621) was an Italian and one of the first Jesuits who became a leading controversialist and apologist due to his theological prowess. He worked closely with two other Doctors of the Church, St. Aloysius Gonzaga and St. Francis de Sales. Among Bellarmine's many accomplishments, his work in the realm of ecclesiology is especially notable, as Fr. John Hardon, SJ, pointed out years ago in a fine essay, "Communion of Saints: St. Robert Bellarmine on the Mystical Body of Christ":

It is significant that Bellarmine went out of his way to

emphasize what seems so obvious to us—that the Mystical Body of Christ is

also the established Church of Christ. Until his time, there were relatively

few Christians not in communion with Rome who claimed that their organization

was the Body of Christ of which St. Paul wrote to the Corinthians: "You are the

Body of Christ, member for member" (I Cor., xii. 27). But with the advent of

Luther and Calvin the situation changed. On the one hand, they preached an

invisible Church founded on faith and predestination; on the other hand, they

called their Church the Body of Christ. This was a new idea and challenge to

traditional Catholic theology.

The Mystical Body of Christ, the predestinarians argued, is

not unlike His tangible physical Body. And since the whole physical Body of

Christ is in heaven and glorified with all its component parts, it follows that

the Mystical Body should also arrive at heavenly glory in all its individual

members. The statement looks harmless enough until we examine its implications.

If every member of the Mystical Body is going to be saved and the Church of

Christ is the Body, then the only members of the Church are those whom God has

eternally decreed should enter heaven. Everyone else is a putative member only,

deceived by God and deceiving himself that he is even a Christian, much less a

part of the Mystical Body.

"My first reaction to this doctrine," Bellarmine observes,

"is that the opposition has pushed the analogy between the mystical and

physical Bodies of Christ far beyond the limits ever intended for them by the

Apostle. They are certainly alive in general outline, but not in every detail.

And besides, even the physical Body of Christ entered heaven and was glorified

only in its formal constituents, but not in all its natural parts, many of

which were lost and changed with the passage of time, as we notice happens in

our own bodies.

So, it is correct enough to say that the whole Mystical Body

will be saved in its constitutive elements, inasmuch as every class in the

Catholic Church—apostles, prophets, teachers, confessors and

virgins—will be represented among the saved. It is not true, however,

that all its material elements, that is, every numerical member of the Mystical

Body, will finally attain to salvation."

This same idea—that external membership does not, in fact, equal certain salvation—was clearly reiterated in Vatican II's Lumen Gentium:

They are fully incorporated in the society of the Church who, possessing the

Spirit of Christ accept her entire system and all the means of salvation given

to her, and are united with her as part of her visible bodily structure and

through her with Christ, who rules her through the Supreme Pontiff and the

bishops. The bonds which bind men to the Church in a visible way are profession

of faith, the sacraments, and ecclesiastical government and communion. He is not

saved, however, who, though part of the body of the Church, does not persevere

in charity. He remains indeed in the bosom of the Church, but, as it were, only

in a "bodily" manner and not "in his heart." All the

Church's children should remember that their exalted status is to be attributed

not to their own merits but to the special grace of Christ. If they fail

moreover to respond to that grace in thought, word and deed, not only shall they

not be saved but they will be the more severely judged. (par 14)

Bellarmine was canonized in 1930 by Pope Pius XI and was named a Doctor the following year.

St. Hildegard of Bingen, of course, was canonized and named a Doctor just last year by Pope Benedict XVI, a fellow German. Hildegard (1098-1179) was one of the most extraordinary women of the medieval era, being a mystic, composer, writer, philosopher, and Benedictine abbess. Medievalist Sandra Miesel, in her 2012 CWR essay, "Hildegard of Bingen: Voice of the Living Light" (January 25, 2012), outlined some of the key events of her life:

Nothing would have seemed extraordinary about Hildegard for

the first half of her long life. She did not wish to publicize the visionary

experiences she had been having since the age of three when a blaze of dazzling

brightness burst into her sight. A diffuse radiance which she called her visio filled her field of vision for the rest of her life

without interfering with ordinary sight. Hildegard came to understand this

phenomenon as “the reflection of the living Light” which conferred the gift of

prophecy and gave her an intuitive knowledge of the Divine.

Hildegard’s visions were not apparitions or dreams. She

scarcely ever fell into ecstasy but rather perceived sights and messages with

the “inner” eyes and ears of her soul. She dictated what she “saw” and “heard”

to secretaries while fully lucid. Because the astonishing images she described

and directed artists to illustrate feature sparkling gems, shimmering orbs,

pulsating stars, curious towers and crenellated walls, modern psychologists

have suggested that Hildegard suffered from a form of migraine called

“scintillating scotomata.” The debilitating illnesses that preceded or

accompanied her visionary episodes might have been migraine attacks. Because

supernatural communications are received according to the capacity of the

receiver, neurology can offer insights on Hildegard’s particular repertory of

forms. But it cannot explain away her experiences or the religious meanings she

assigns to them. These were genuine occasions of contact between Hildegard and

God.

In 1141—on a date she was careful to record exactly—heaven

opened upon Hildegard as “a fiery light of exceeding brilliance” and a mighty

voice commanding her to “tell and write” what she sees of God’s marvels. Like

Jeremiah and several other prophets, Hildegard quailed at her call. Pleading

her sickly female constitution and lack of formal education, she fell ill. But

she confided in the convent’s provost, who shared the matter with his abbot at

Disibodenberg who urged Hildegard to accept her call. She rose from her bed and

set to work on her first book, Scivias.

Hildegard also asked advice from Bernard of Clairvaux who

also encouraged her. Meanwhile, her local abbot notified the archbishop of

Mainz who mentioned Hildegard to Pope Eugenius III, then visiting Germany.

After a papal commission reviewed chapters of Scivias, the pope approved Hildegard’s writings and read

portions to a regional synod at Trier in 1147.

Hildegard's music has been surprisingly popular in recent years. A great guide to her compositions is Dr. Christopher Morrissey's 2012 CWR piece, "A Beginner’s Guide to the Music of St. Hildegard of Bingen", along with Catherine Harmon's post, "St. Hildegard of Bingen: A playlist for the new Doctor of the Church".

Communion of Saints: St. Robert Bellarmine on the Mystical Body of Christ

Communion of Saints: St. Robert Bellarmine on the Mystical Body of Christ | John A. Hardon, S.J.

Shortly after his defection from Rome, Johann Döllinger

bitterly reproached the First Vatican Council with "doing nothing but defining

the private opinions of a single man—Cardinal Robert Bellarmine." The

accusation is false but suggestive, because it leads us to investigate the

teaching of St. Robert on the organization of the Catholic Church as the

Mystical Body of Christ. Most of the Council's business had to deal with the

origin and nature of the one true Church. Moreover, Bellarmine's ecclesiology

was the main source from which the Fathers of the Council drew their decrees

and definitions. Consequently, with the current interest even among

non-Catholics in the Church of Christ as the Mystical Body, we should not

overlook what St. Robert Bellarmine has to say about a subject in which the

Church herself considers him the outstanding authority.

Pope Pius XII, in his Encyclical Mystici Corporis, confirms this authority when he quotes St. Robert

to support his explanation of why the social Body of the Church should be

honored with the name of Christ. "As Bellarmine notes with acumen and

accuracy," the Pope says, "this naming of the Body of Christ is not to be explained

solely by the fact that Christ must be called the Head of His Mystical Body,

but also by the fact that He so sustains the Church, and so in a sense lives in

the Church, that it is, as it were, another Christ." [1] So much for an

apologetic of Bellarmine's qualifications. What follows is a synthesis of his

doctrine on the Mystical Body taken from his sermons and controversies, which,

it is hoped, will help to amplify several points of detail which the Mystici

Corporis only suggests but otherwise does

not develop or dwell upon.

The Mystical Body of Christ Is the Catholic Church

It is significant that Bellarmine went out of his way to

emphasize what seems so obvious to us—that the Mystical Body of Christ is

also the established Church of Christ. Until his time, there were relatively

few Christians not in communion with Rome who claimed that their organization

was the Body of Christ of which St. Paul wrote to the Corinthians: "You are the

Body of Christ, member for member" (I Cor., xii. 27). But with the advent of

Luther and Calvin the situation changed. On the one hand, they preached an

invisible Church founded on faith and predestination; on the other hand, they

called their Church the Body of Christ. This was a new idea and challenge to

traditional Catholic theology.

The Mystical Body of Christ, the predestinarians argued, is

not unlike His tangible physical Body. And since the whole physical Body of

Christ is in heaven and glorified with all its component parts, it follows that

the Mystical Body should also arrive at heavenly glory in all its individual

members. The statement looks harmless enough until we examine its implications.

If every member of the Mystical Body is going to be saved and the Church of

Christ is the Body, then the only members of the Church are those whom God has

eternally decreed should enter heaven. Everyone else is a putative member only,

deceived by God and deceiving himself that he is even a Christian, much less a

part of the Mystical Body.

"My first reaction to this doctrine," Bellarmine observes,

"is that the opposition has pushed the analogy between the mystical and

physical Bodies of Christ far beyond the limits ever intended for them by the

Apostle. They are certainly alive in general outline, but not in every detail.

And besides, even the physical Body of Christ entered heaven and was glorified

only in its formal constituents, but not in all its natural parts, many of

which were lost and changed with the passage of time, as we notice happens in

our own bodies.

So, it is correct enough to say that the whole Mystical Body

will be saved in its constitutive elements, inasmuch as every class in the

Catholic Church—apostles, prophets, teachers, confessors and

virgins—will be represented among the saved. It is not true, however,

that all its material elements, that is, every numerical member of the Mystical

Body, will finally attain to salvation." [2]

Calvinists and The Mystical Body

Another argument, of the Calvinists particularly, was that

the only Church of which Christ may be said to be the Head is the one which He

will eventually save and "set before Him on the Day of Judgment—glorious

and without spot or wrinkle," as described by the Apostle in his Epistle to the

Ephesians. However, since only the predestined will be saved and glorified,

only they are properly to be considered members of the Church of Christ.

St. Robert answers: "It all depends on how you understand

the expression, 'His Church.' If it is taken to mean that Christ is Head only

of that part of 'His Church' which He will save, then the proposition is false.

Christ is Head of the whole Mystical Body, in spite of the tragic fact that

certain people who are now its members, will be lost for all eternity. But if

'His Church' is understood to include the whole body of the faithful as

distinguished from the societies of unbelievers, then the proposition is true,

while the conclusion deduced from it is false. For although some members of

this Church will not be saved, it is wrong to conclude that therefore Christ does

not save His Church, of which He is the Head." [3]

However, Bellarmine does not limit his concept of the

Mystical Body to the visible Church on earth. The Mystical Body of Christ is

composed of three "Churches"—the Church Militant, the Church Suffering and

the Church Triumphant. He has as little sympathy with those who denied

membership in the Body of Christ to the souls in purgatory and the Saints in

heaven, as he had with anyone who restricted its membership to the predestined

and elect or extended it to those who were united only by a common, internal

faith in Christ.

Bellarmine Defends Honoring the Saints

In his defense of the Holy Eucharist against the Calvinists,

St. Robert had to answer some of their stock charges on the traditional custom

of offering the Holy Sacrifice in honor of the Saints. He explains that the

Protestant bias against this practice arises form two fundamental errors in

their theology: one a misunderstanding of Catholic doctrine, where they claim

that we offer the Mass as an act of adoration to the Saints instead of to God;

the other is an unwarranted limitation of membership in the Mystical Body. "The

practice of offering Holy Mass to honor the Saints," he says, "is especially

appropriate as a public expression of our belief in the Communion of Saints.

The Sacrifice of the physical Body of Christ is an oblation of the corporate

Mystical Body of Christ. Moreover, since we do not hesitate to mention the

names of living persons, such as the Pope and bishop, in the ritual of the Mass,

why should we fail to remember those of the faithful departed who are in heaven

or in purgatory, when all of them belong to the same Body of the Lord?

According to St. Augustine, there is no better way of fulfilling the one great

purpose for which the Eucharistic Sacrifice was instituted, than that it might

symbolize the universal sacrifice in which the whole Mystical Body of Christ

—the whole regenerated City of God—is offered by the hands of the

great High Priest to the glory of His Heavenly Father. Once we recognize the

Saints, no less than we, are organically united to the Mystical Body, it

becomes not only proper but necessary that their memory should be recalled

during the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass." [4]

Membership in The Mystical Body

In general, however, when Bellarmine speaks of the Mystical

Body, he has in mind only the first of its three branches, the Church

Militant—or, in other words, the visible organization of the Roman

Catholic Church. Thus, in treating the delicate question of occult infidels, he

refutes the doctrine of Calvin who held that, if a baptized person has lost the

virtue of faith, in spite of his external profession of belief and conformity

with Christian practice he is no longer a member of the organic Body of Christ.

"It is certainly true," he admits, "that a sincere faith and not its mere

external profession is required if we are to be internally united to the Body

of Christ, which is the Church . . . . But even the man who makes only an

outward profession along with the rest of the faithful is a true member, albeit

a dry and dead member, of the Body of the Church." [5]

It follows, therefore, that the Mystical Body of Christ is

the Roman Catholic Church, whose members are all those who have been baptized

and who at least externally practice and profess the true faith. Commentators

on the Mystici Corporis make special

note of the fact that, after centuries of controversy on the subject, the Pope

has authoritatively approved Bellarmine's doctrine on the minimum essentials

for membership in the Mystical Body—which reads like a paraphrase from

the third book of St. Robert's De Conciliis. In the words of Pope Pius XII, "only those are

really to be included as members of the Church who have been baptized and

profess the true faith and have not unhappily withdrawn from Body-unity, or for

grave faults been excluded by legitimate authority. For in one Spirit were we

all baptized into one Body." [6]

Sinners as Members of The Mystical Body

John Wyclif, and after him the Protestants in general,

allowed that all the justified in the state of grace, and only they, are

members of the Mystical Body. Even Catholic theologians like de Soto and Cano,

when they came to explain how sinners are members of the Body of Christ, gave

them analogous membership and nothing more. They admitted that baptized persons

in the state of sin may be called "the faithful" and "Christians," but only in

the sense that they are somehow externally attached to the Body of the Church.

"Not only the organs and limbs," they argued, "but also bodily secretions, the

teeth, the hair, and such like, all belong to the body." Bellarmine refused to

accept this view. "If what they say is true, the consequences are impossible. A

wicked Pope then is not the Head of the Church, and other bishops, if they are

in sin, are also not heads of their respective churches. For the head is not a

bodily secretion or the hair, but a member of the body—indeed, its most

important member."

"To solve the difficulty, therefore, we have to distinguish

two senses in which a member of the body may be understood. It may be taken in

the strict sense to designate the member in itself, in its essence and

substance as a member. Or it may mean a member of the body in its capacity as a

medium of activity through which the body operates. Thus, for example, the eye

of a man and the eye of a horse are specifically different as substances or

entities because they are radicated specially different souls. But as kinetic

instruments they are specifically the same because both have the same end and

object of their operation—both being directed to the sensible perception

of color.

"An evil bishop, a bad priest, a layman in grievous sin are

dead members of the Body of Christ, and therefore not true members, if we

understand 'member' in the strict sense of an integral part of a living body.

However, these same 'dead members' are very vital members if we consider them

as instruments of activity within the Church. So that the Pope and bishops are

real heads, the teachers and preachers are real eyes and tongues of the Body of

Christ, even when they have fallen from the grace of God. For while it is true

that a Christian becomes a living member of this Body through charity, yet in

the Providence of God the instruments of operation in the Church are

constituted by the power of orders and jurisdiction, which can be obtained and

exercised even by a man who is personally an enemy of God.

"Hence the great difference between a physical body, in

which a dead member cannot serve as a vital instrument, and the supernatural

Mystical Body, where this is not only possible but actually happens. To explain

the paradox we should recall that in natural bodies their work depends entirely

on the health and soundness of the organs by which they act. But the Mystical

Body of Christ can operate independently of the virtue and vitality of its

members, because the soul of this Body, which is the Holy Spirit, can function

equally through good instruments as through bad, through instruments that are

alive as through those which are dead." [7]

The Functions and Parts of The Mystical Body

For seven years, starting in 1568, Bellarmine taught

theology at Louvain, where he met and successfully routed Michael de Bay,

father of Baianism and author of the pernicious theory that man can live the

life of friendship with God even before Baptism and without the remission of

sins. During this time he also preached every week at the Cathedral to a mixed

congregation of Catholics and non-Catholics, some of whom came all the way from

Elizabethan England just to hear him speak. About a hundred of these discourses

have come down to us, among them a panegyric on Our Lady, given on the Feast of

her Nativity, in which the Saint recalled that this was the anniversary of

another sermon preached not far away by Martin Luther, when he blasphemously

attacked the sanctity of the Mother of God, telling his audience that: "She has

no more intercessory power with God than you or I, because she is no more holy

than we."

Bellarmine launched into what perhaps the most bitter attack

on any opponent that can be found in all his extant writings. Best of all,

though, is the occasion which this defense of Mary's sanctity gave him to

reveal her transcendent position in the Mystical Body of her Divine Son.

"The Church," he explains, "is a most beautifully organized

and stately Body of which Christ, the God-man, is the Head. 'For the Lord hath

made Him Head over all the Church,' as the Apostle says. What is the Head? It

is the principle and governing force of the Body. Christ is, therefore, the

Head because, as He tells us, 'I am the principle who speak with you.' In what

way is the head superior to the other members of the body? In this that, while

the rest of the body is possessed of only one bodily sense and that the most

ignoble, the head is gifted with all the senses, including the sense of touch.

Christ is, therefore, the Head in whom are the eyes of His providence, by which

He watches over us; the ears of His mercy, by which He listens to our prayers;

the nostrils of His justice, by which after death He will separate the good

from the wicked and who have lived among us; and the palate of experience, by

which He tries the virtue and fidelity of the least and the greatest of us.

"What is the special function of the head? To give sense and

movement to the other members. So, Christ is the Head because He freely gives

life and movement, that is faith and charity, and all the virtues, to the

faithful members who compose His Body. And although at times and to a limited

degree He permits, or rather commits, to mere man the function of certain

senses (like the sense of sight to teachers, of speech to preachers, of sight

and smell and hearing to pastors), yet He always reserves to Himself the

faculty of giving life and motion, which is the special prerogative of the head

of every body." [8]

The Holy Spirit in The Mystical Body

Anticipating by three centuries the doctrine of the Mystici

Corporis in which Pope Pius XII attributes

to the Holy Spirit the invisible principle of life in the Mystical Body,

Bellarmine declares: "The Heart, which is in the center of the Body, and which,

although itself unseen, mysteriously nourishes the parts that are seen, is the

Holy Ghost. For He is not clothed with human flesh and thus made visible, like

the Head, who is Christ our Lord. They rant, therefore, who madly assert that

Melchisedech or one of the prophets is the Holy Spirit. No, the Spirit of

Christ is not visible to human eyes, and yet it is He who governs and feeds and

keeps alive the Body of Christ, which is the Catholic Church." [9]

Bellarmine lived in the period of horrible transition from

orthodoxy to heresy, when Calvin was teaching the people that there is no

priesthood and no hierarchy, when Luther was calling the Pope "Antichrist" and

bishops and priests "destroyers of human souls."

But if the Church which Christ established is His Body, this

Body must have shoulders, and these shoulders, according to Bellarmine, are the

Apostles, and the Roman Pontiffs, bishops and priests who have succeeded them.

"We are accustomed to placing burdens on our shoulders," he writes, "and so

also Christ has done, by placing the burden of the Church's government on the

shoulders of the Apostles and their priestly successors. It follows, therefore,

as the Fathers of the Church keep reminding us, that the episcopal office is

not so much a dignity as a heavy responsibility. Hence also, the Supreme Pastor

of souls, on whom rests the heaviest burden of all, appropriately calls himself

the servant of the servants of God." [10]

There are two sorts of enemies with whom the Church has had

to contend in the course of her history: pagans and infidels from without, and

heretics from within her ranks. Against both of these Christ has endowed His

Mystical Body with adequate means of defense. Bellarmine conceives the martyrs

and teachers of the Catholic Church as the arms of the Mystical Body. "What are

the martyrs," he asks, "but the arms of the Body of Christ—men and women

who fight with the sword of God's word and conquer the enemies of His name by

the shedding of their blood? And not only the martyrs but the teachers of

Christ's doctrine are the arms of His Body. Both are equally necessary to

combat the forces of evil that are aligned against the Church. Pagans and the

spirit of idolatry are met and defeated by the martyrs; heretics and apostates

by the teachers. If the most painful kind of death is martyrdom, the most

dangerous kind of life is to teach the truth. To both has Christ promised the

reward of victory, not only in heaven, but over their enemies even here on

earth." [11]

Protestant Assaults on The Practice of Celibacy

An unfamiliar side of the Protestant revolt was the

disgraceful way in which the self-appointed reformers of the Church's morals allied

themselves against her doctrine and practice of celibacy. In a rhetorical

passage of his "Babylonian Captivity," Luther pleaded with "the prisoners of

the monastic life" to break the chains which bound them to their monasteries

and to serve Christ with the untrammeled liberty of the children of God. If any

of them still hesitated to accept the responsibilities of marriage, he argued,

let them remember that this is only a ruse of the devil who would have them

reverse the order of divine providence and obey man rather than God.

Against this background it is easier for us to sympathize

with the strong feeling to which Bellarmine would give expression whenever he

wrote on the subject of virginity. "Virgins," he believes, "are the vitals of

the Mystical Body, comparably close to God as the vitals of a physical body are

close to the human heart. If only the swillers, gluttons and lechers among the

heretics understood how pleasing is virginity in the eyes of God, how 'they

follow the Lamb wherever He goes, singing a new song before the throne which no

one else can sing' (Apoc., xiv. 3, 4)! If only they would read the promise

which the Lord had spoken through the prophet Isaias: 'Let not the eunuch say:

"behold I am a dry tree." For thus saith the Lord to the eunuchs; 'I will give

to them in My house and within My walls a place and a name better than sons and

daughters. I will give them an everlasting name which shall never perish' (Is, lvi.

3, 4). But the enemies of the Church will not read and will not understand. If

only they realized that, by forcing consecrated virgins to marry, they are

tearing at the very entrails of the Mystical Body and robbing it of its dearest

possession. If only they realized this, I say, they would not so readily

debauch the minds of the young with their devilish doctrine about the

unchristian character of celibacy." [12]

Mary's Place in The Mystical Body

In a way, the most inspiring feature of Bellarmine's

theology of the Mystical Body is the place which he assigns within it to the

Blessed Mother of God: "The Head of the Catholic Church is Jesus Christ, and

Mary is the neck which joins the Head to its Body." Because she has merited so

well of God by her perfect conformity to His holy will, He has decreed that

"all the gifts and all the graces which proceed from Christ as the Head should

pass through Mary to the Body of the Church. Even the physical body has several

members in its other parts—hands, shoulders, arms and feet—but only

one head and one neck. So also the Church has many apostles, martyrs,

confessors and virgins, but only one Head, the Son of God, and one bond between

the Head and members, the Mother of God. By virtue of her transcendent merits

before God, the Blessed Virgin stands closer than any other creature to the

Head of the Mystical Body; it is no exaggeration to say that she unites the

Head to the Body, and that therefore through her, before all others, flow the

heavenly blessings from the Head, who is Christ, to us who are His members." [13]

The doctrine of the Mystical Body is anything but sterile

theology. Among the practical consequences which St. Robert derives from our

incorporation in Christ is the motive which it gives for the practice of

fraternal charity. The Saints in heaven intercede for the souls in purgatory, he

says, because they are both members of the same Body. The souls in purgatory

intercede for each other because they are also members of one Body; the Saints

and poor souls intercede for us because we are one Body with them, member of

member; and we are moved to pray for each other on earth, to ask for favors

from the Saints in heaven, and to pray for the souls in purgatory because

"together with them we form one Church and one Body, united by the bond of the

same charity in the Kingdom of Christ." [14]

ENDNOTES:

[1] Mystici Corporis,

English Translation (American Press, 1943), p. 24.

[2] De Ecclesia Militante, lib. III, cap. 7.

[3] Ibid.

[4] De Eucharistia,

lib. VI, cap. 8.

[5] De Conciliis,

lib. III, cap. 10.

[6] Mystici Corporis,

p. 12.

[7] De Ecclesia Militante, lib. III, cap. 7.

[8] Concio xlii de Nativitate B.V.M.

[9] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

This article originally appeared in the November/December

2000 issue of Catholic Faith.

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles and Book Excerpts:

• The Essential Nature and Task of the Church | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• On the Papacy, John Paul II, and the Nature of the Church |

Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• Peter and Succession | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• Motherhood of the Entire Church | Henri de Lubac, S.J.

• Mater Ecclesia: An Ecclesiology for the 21st Century |

Donald Calloway, M.I.C.

• The Church Is the Goal of All Things | Christoph Cardinal Schönborn

• Excerpts from Theology of the Church | Charles Cardinal Journet

• Church Authority and the Petrine Element | Hans Urs von Balthasar

• Authority and Dissent in the Catholic Church | Dr. William E. May

• Understanding The Hierarchy of Truths | Douglas

Bushman, S.T.L.

• Ignatius of Loyola and Ideas of Catholic Reform | Vince Ryan

• The Counter-Reformation: Ignatius and the Jesuits | Fr.

Charles P. Connor

• When Jesuit Were Giants | Interview with Father Cornelius

Michael Buckley, S.J.

• The Jesuits and the Iroquois | Cornelius Michael Buckley, S.J.

• The Tale of Trent: A Council and and Its Legacy | Martha Rasmussen

• Reformation 101: Who's Who in the Protestant Reformation |

Geoffrey Saint-Clair

• Why Catholicism Makes Protestantism Tick | Mark Brumley

Father

Father John Hardon, S.J. (b. June 18th, 1914 - d. December 30, 2000) was the

Executive Editor of The Catholic Faith magazine. He was ordained

on his 33rd birthday, June 18th, 1947 at West Baden Springs, Indiana. Father

Hardon was a member of the Society of Jesus for 63 years and an ordained

priest for 52 years. Father Hardon held a Masters degree in Philosophy from

Loyola University and a Doctorate in Theology from Gregorian University

in Rome. He taught at the Jesuit School of Theology at Loyola University

in Chicago and the Institute for Advanced Studies in Catholic Doctrine at

St. John's University in New York. A prolific writer, he authored over forty

books, including The Catholic Catechism, Religions of the World, Protestant

Churches of America, Christianity in the Twentieth Century, Theology of

Prayer, The Catholic Lifetime Reading Plan,

History And Theology Of Grace ,

With Us Today: On the Real Presence of

Jesus Christ in the Eucharist , and The

Treasury Of Catholic Wisdom , which he edited.

In addition, he was actively involved with

a number of organizations, such as the Institute on Religious Life, Marian

Catechists, Eternal Life and Inter Mirifica, which publishes his catechetical

courses. For more about Fr. Hardon, visit this

page at Dave Armstrong’s website.

China's Modern Martyrs: From Mao to Now (Part 2)

China's Modern Martyrs: From Mao to Now (Part 2) | Anthony E. Clark, Ph.D. | CWR

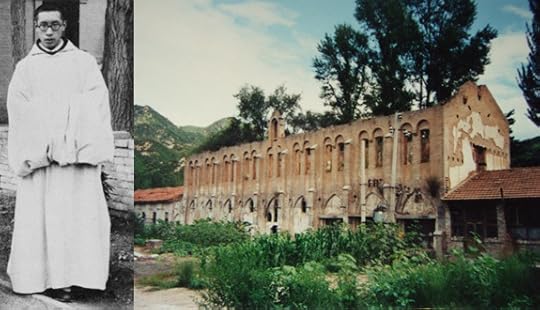

The little-known story of the murder of 33 Trappist monks by Chinese Communists in 1947

Editor's

note: Part 1 of “China's Modern Martyr's: From Mao to Now” was published on June 13, 2013.]

Part

2, Torments

“The

body of Christ which is the Church, like the human body, was first

young, but at the end of the world it will have an appearance of

decline.” — St. Augustine

As

I sat with Brother Marcel Zhang, OCSO (b. 1924), in his Beijing

apartment, I thumbed through his private photographs of Yangjiaping

Trappist Abbey. Some were taken before

its destruction in 1947, and some he had taken during a recent visit

to the ruins. What was once a majestic abbey church filled with

divine prayer and worship had been reduced to debris and an

occasional partial outline of a gothic window. When the People’s

Liberation Army (PLA) attacked the monastery in 1947 and began its

cruel torments against the monks, Zhang was one of the monks. He

shared with me some of his recollections, no doubt at great risk. As

we looked at a picture of the Abbey church as it appears today, where

the monks gathered for daily Mass prior to 1947, Zhang paused to

contemplate the ruins. “It’s already gone . . . already, the

church is like this,” he said, insinuating that the ruins of the

Abbey “church” metaphorically represented the “Church” in

China, still haunted by the past, still tormented in the present.

_______

After

the People’s Court had demanded the collective execution of the monks

of Our Lady of Consolation Abbey at Yangjiaping, the Trappists were

bound in heavy chains or thin wire, which cut deeply into their

wrists, and were confined to await their punishments. Brother Zhang

recalled that during the many trials, Party officials presiding over

the interrogations accused the Trappists of being, “wealthy

landlords, rich peasants who exploit poor peasants,

counterrevolutionaries, bad eggs, and rightists”. Essentially, they

were charged with all of the “crimes” commonly ascribed to the

worst classes in the Communist list of “bad elements.”

Normally, only one of these accusations was sufficient to warrant an

immediate public execution, but some of the accused from the abbey

were foreigners, and news that Nationalist forces were on their way

to save the monks alarmed the Communist officers. Punishments had to

be inflicted on the road, on what became the Via

Crucis of the Trappist

sons of Saint Benedict. More interrogations were staged during stops,

and Brother Zhang noted that new trials, or “struggle sessions”

(鬥爭)

as he called them, were orchestrated at every village. Zhang himself

was questioned more than twenty times at impromptu People’s Courts.

He remembered that he was treated with much more leniency than the

priests, as he was still only a young seminarian in 1947. The priests

were much more despised. “After the interrogations,” Zhang

recalled, “we would go out to relieve ourselves, and I saw the

buttocks of the priests, which were red [from their beatings]; the

flesh hung off like meat.”

Chinese Catholics who know about the Yangjiaping incident refer to

these torments as a “siwang

xingjun,” 死亡行軍

or

a “death march,” and this is when most of the Trappists who died

received their “palms of martyrdom.”

The

Death March: A Trappist “Way of the Cross”

Late

in the evening of August 12, 1947, the feast of St. Clare of Assisi,

one of the Communist officials who had ordered the severe beatings at

the People’s Court, Comrade Li Tuishi, gathered the wearied monks

for their march.

September 16, 2013

Pope's former professor: Francis never supported a Marxist-based liberation theology

A new book from Ignatius Press featuring interviews with several professors, students, colleagues, and friends who were close to Cardinal Bergoglio prior to his election this past spring sheds light on his views of liberation theology. A recent piece for Catholic News Agency reports:

The book, Pope Francis: Our Brother, Our Friend—Personal Recollections about the Man Who Became Pope, is edited by Alejandro Bermúdez, Executive Director of the Catholic News Agency, and is now available from Ignatius Press in both hardcover and electronic book format.

Pope Francis and the Missionary Spirit

Pope

Francis and the Missionary Spirit | Fr. James V. Schall, SJ | CWR

We are

called to preach and proclaim the Gospel “courageously and in every

situation.”

“The

Church—I repeat once again—is not a relief organization, an

enterprise nor an NGO (Non-Government Organization), but a community

of people, animated by the Holy Spirit, who have lived and are living

the wonder of the encounter with Jesus Christ and want to share their

experience of deep joy, the message of salvation that the Lord gave

us. It is the Holy Spirit who guides the Church in this path.”

— Pope

Francis, Message

for World Day of Peace (L’Osservatore Romano, August 28,

2013)

I.

In

contrast with his usual custom of keeping what he says brief and to

the point, Pope Francis wrote a fairly long message (about one full

page in L’Osservatore Romano) for Mission Sunday, which will

be observed on October 20, 2013. This letter is rather wide ranging.

It strikes me as giving more insight into what Pope Bergoglio is

about than almost anything I have previously come across, except

perhaps Lumen Fidei.

This

Pope’s evident optimism has always puzzled me because he does have,

at the same time, a pretty good grasp of the real and growing

obstacles to the presence of Christianity in almost every sector of

the world and its culture. Near the end of this Message, for

instance, Pope Francis tells us:

I wish to say a word about those Christians, who, in various parts of

the world, encounter difficulty in openly professing their faith and

in enjoying the legal right to practice it in a worthy manner. They

are our brothers and sisters, courageous witnesses—even more

numerous than the martyrs of the early centuries—who endure with

apostolic perseverance many contemporary forms of persecution. Quite

a few also risk their lives to remain faithful to the Gospel of

Christ.

Continue reading on the CWR site.

A Simple Secret for Better Sex, Marriages, Health and Society

A

Simple Secret for Better Sex, Marriages, Health and Society

| Carrie Gress | CWR

Secular news sources and authors are "discovering" what the Church has been saying for decades

A

quick look at a few articles and books from unlikely places is

confirming what the Church has known for many decades. Want better

sex? And stronger marriage? Hope to avoid breast cancer? Want fewer

social problems? Don’t contracept.

Better

Sex

The

first surprising article, which received a lot of attention when it

came out a few months ago, discussed a

new study in U.S.

News and World Report that

asked which demographic has the best sex life. It seem that

weekly-Mass-attending Catholics "have the most enjoyable and

frequent sex."

The

study, done by the Family Research Council, generally pointed to

weekly church-going, monogamous married couples as the happiest. What

is interesting is that many religious denominations could fit under

that model, but the FRC report specifically speaks about Catholics.

And what is it that Catholics don't do [or shouldn't do] that most of

their Protestant counterparts do? Contracept.

The

study did say that knowing one partner was a significant factor in

the couples' evaluations. One can speculate that better sex, as a

result of increased communication and self-giving that comes to a

couple when they don't use contraception, also translates into

stronger marriages.

Those

involved with infidelity and porn, the study reported, not only did

not rate high among those satisfied with their sexual activity, but

was also linked to such negative effects as "poverty, domestic

abuse, crime, drug addiction and loss of job."

Fewer

Divorces

Among

non-contracepting couples, the divorce rate is under 5%, which is

appealing enough, but it appears that there are other dividends. A

recent

story in the Los

Angeles Times

shows that not only parents who are open to life are less likely to

get divorced, but so are their children. "Children with a lot of

siblings are more likely to marry – and stay married – than are

only children or those who grew up with one or two siblings,"

the article explains.

September 14, 2013

The Parable of the Perfect Father

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Sunday, September 15, 2013 | Twenty-fourth

Sunday in Ordinary Time | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Ex 32:7-11, 13-14

• Ps 51:3-4, 12-13, 17, 19

• 1 Tim 1:12-17

• Lk 15:1-32

The

parable of the prodigal son is well known, arguably the most famous

of Jesus’ parables. Yet, as Scripture scholar Joachim Jeremias

states in The Parables

of Jesus (New York,

1963), it “might more correctly be called the parable of the

Father’s Love…”, for it is a powerful and unforgettable

depiction of God’s love and mercy.

While

the two sons are decidedly human—sinful, self-centered,

materialistic—the father exhibits a serene, pervasive holiness that

reveals the heart of the heavenly Father. In Dives

in misericordia, his

encyclical on the mercy of God, Pope John Paul II noted that although

the word “mercy” doesn’t appear in the famous parable, “it

nevertheless expresses the essence of the divine mercy in a

particularly clear way.” Read carefully, the parable offers a

wealth of insight into our relationship with our heavenly Father; it

offers a glimpse of the Father’s face. But it also is a mirror that

confronts us with our own distorted priorities and self-centered

attitudes.

For example, the younger son’s

request for his share of the estate was not just an impulsive,

youthful demand for autonomy, but a harsh renunciation of his father.

In essence, his demand was a way of publicly declaring, “I wish you

were dead!” The son, wrote St. Peter Chrysologus, “is weary of

his father’s own life. Since he cannot shorten his father’s life,

he works to get possession of his property.” In rejecting his

father and the life-giving communion he once had with him, he lost

the privilege of being a son and embarked upon a calamitous course.

As a father myself, I think it is safe

to say that most ordinary fathers would have objected to the son’s

request, even refused to consider it. Yet our heavenly Father does

not object; he respects our

freedom—his great gift to us—even when we use it to rebel against

him. So the father divided up the property; in doing so, grace was

destroyed and communion was severed. The familial bond was broken,

and the son took his money into the “far country,” a reference to

a place of utter emptiness and spiritual desolation.

“What

is farther away,” asked St. Ambrose, “then to depart from

oneself, and not from a place? … Surely whoever separates himself

from Christ is an exile from his country, a citizen of the world”

The physical distance was not as painful as the loss of familial love

and embrace; the son’s inner life vanished as quickly as did his

inheritance. He is soon faced with eating unclean swill while tending

unclean animals, the swine.

How

did the son come to his senses? An answer can be found in today’s

epistle, in which St. Paul confesses his sins of blasphemy,

persecution, and arrogance, and explains he has “been mercifully

treated because I acted out of ignorance in my unbelief.” By God’s

grace he—a prodigal son—recognized his sinfulness. Confronted by

Christ on the dusty road to Damascus, he experienced divine grace and

mercy.

The

prodigal son knew his father had every right to disown him, to

consider him dead and gone. But he was willing to admit his sin and

become a nameless hired hand. Yet, even as he tried to articulate a

cry for mercy, he was wrapped in mercy—held, kissed, clothed, and

restored to life. Having walked away in petulant selfishness, the son

had embraced death; having been embraced by his patient and

compassionate father, he was restored to life.

John

Paul II explained that God is not just Creator, but “He is also

Father: He is linked to man, whom He called to existence in the

visible world, by a bond still more intimate than that of creation.

It is love which not only creates the good but also grants

participation in the very life of God: Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

For he who loves desires to give himself.” The merciful Father

waits for the dead, eager to clothe them with new life.

(This is "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the September 12, 2010, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

The Holy Cross is an invitation to faith, to life, to love

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Saturday, September 14, 2013 |

Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Num 21:4b-9

• Ps 78:1bc-2, 34-35, 36-37, 38

• Phil 2:6-11

• Jn 3:13-17

“By its elevation, the Cross is like

an appeal to the whole creation to adore the blessed Passion of

Christ our God who was suspended on it, for Christ destroyed by this

Cross the one who had destroyed us.”

These words, from the Vespers

celebrated on this feast day by Byzantine Catholics, proclaim some of

the mystery, hope, and paradox of the Holy Cross. There is the

mystery of the death of the God-man, the hope of salvation because of

His death and Resurrection, and the paradox of finding joy in such a

bloody reality. In the words of the Crucified One, prior to His

ascent onto the Cross: “And when I am lifted up from the earth, I

will draw everyone to myself” (Jn 12:32).

Today’s Epistle and Gospel readings

focus on the relationship between the Incarnation—the entrance of

God into history as the man Jesus Christ—and the exaltation of the

Incarnate One by His death on the Cross. That relationship is, of

course, at the heart of Christianity, for belief in the Incarnation

and the salvific work accomplished on the cross are central for

Christians. If Jesus was not truly God and truly man, Christianity is

simply another school of ethics; if the Passion and Resurrection did

not take place, Catholicism is merely a ritualized exercise in empty

piety.

The reading from Paul’s Epistle to

the Philippians is a great Christological hymn offered in

thanksgiving for the Incarnation. Although the Son was equal to the

Father, He emptied Himself. What does that mean? Much scholarly ink

has been spilled over this difficult theological question, but the

essence of this emptying, or kenosis, is the perfect

acceptance of God’s will. The willingness of the Son to be sent by

the Father for the salvation of man is a major theme in the Gospel of

John. “You know me and also know where I am from,” Jesus declared

in the Temple, “Yet I did not come on my own, but the one who sent

me, whom you do not know, is true” (Jn 7:28).

This can also be seen in the third

chapter of John, in which Jesus states that God “gave his only Son”

and sent His Son into the world so “the world might be saved

through him.” In that same discourse to Nicodemus, Jesus stated

that no one has gone up to heaven except the one who has come down.

This is one of many claims to divinity made by Jesus, who foretold

His death, Resurrection, and Ascension, even as He revealed that He

had been sent by and from the Father in heaven.

This raises a

significant point about the Cross: it is not a sign of God’s wrath,

but a concrete demonstration of His love for man. The Romans used the

cross to punish, kill, and control. God used the altar of the Cross

to forgive, to destroy death, and to offer eternal life.

“Accordingly, in the New Testament the Cross appears primarily as a

movement from above to below,” wrote Joseph Ratzinger in

Introduction to Christianity, “It stands there, not as the work

of expiation that mankind offers to the wrathful God, but as the

expression of that foolish love of God’s that gives itself away to

the point of humiliation in order thus to save man; it is his

approach to us, not the other way about.”

The Cross, then, is an invitation to

faith, to life, to love. It is a revelation of the nature of God. It

is also a sign of contradiction and a source of scandal. This is what

Jesus meant when He spoke of being lifted up. I know people who, when

they see a crucifix, are disgusted and appalled. I also know a young

lady who, after being an atheist for several years, finally crumbled

on her knees before a crucifix and wept, broken and healed.

“We exalt his Name with great

rejoicing,” continue the Vespers, “and glorify his infinite

condescension.” Amen!

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the September 14, 2008, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

September 13, 2013

"Every Baptized Person Is Called To Evangelize" by Francis Cardinal Arinze

Chapter 1 of The Layperson's Distinctive Role

When

our beloved Lord and Savior Jesus Christ was inaugurating the Kingdom

of God, he called people to come after him. ‘‘Follow me’’ is

the invitation he gave to his first disciples (Mt 4:19; Mk 1:17; Lk

This important book by the highly regarded African prelate, Cardinal

Arinze, describes in positive and simple terms who the lay person is,

his distinctive role in the Church, and how the lay apostolate

distinguishes the lay faithful from the clergy and the religious.

The call of lay people to be witnesses of Christ in the ordinary

areas of secular life, such as family, work, recreation, politics and

government, shows how demanding the apostolate of the lay people is. The

book draws from the dynamic teachings of the Second Vatican Council,

the riches of the 1987 Synod of Bishops on the Lay Faithful, and the

emphasis on the lay apostolate by recent Popes, to present to lay people

an attractive and demanding call to witness to Christ in society.

Leaders and participants of various lay groups and movements will

find this book liberating and encouraging. Clerics and religious will

find these considerations by Cardinal Arinze of great help, both in

appreciating the limits of their own apostolates and of seeing how to

put before the lay faithful the demands of their calling.

Cardinal Francis Arinze grew up in Nigeria, became the

youngest Bishop in the world, and the first African Cardinal to head a

Vatican office. He was the head of the Congregation for Divine Worship

and the Discipline of the Sacraments. His biography, God's Invisible Hand, was published by Ignatius Press as well as Celebrating the Holy Eucharist.

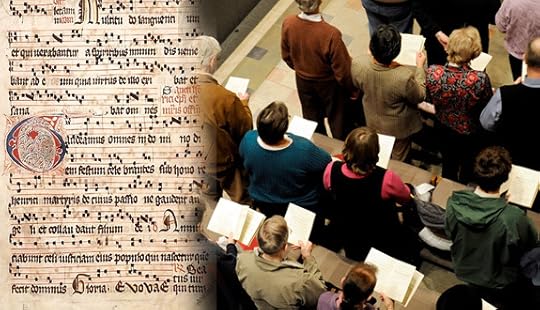

Church Fathers and Church Music

Church Fathers and Church Music | Christopher B. Warner | CWR

The Fathers of the Church can help us refine our liturgical worship after 50 years of subjection to sentimental pop music.

At the beginning of this 50th

anniversary year of Vatican II, Benedict XVI called for a renewed, authentic

reading and implementation of the council documents. After suffering through

many decades of vulgar, saccharine Church music, it is encouraging to note a

rise of musicians who are serious about authentic reform of sacred worship. The

recent Sacred Liturgy Conference in Rome was a great success, and there is a

spirit of joyful, liturgical rejuvenation among the youth. Today’s composers

are considering many facets of sacred music theory and history as they strive for

the renewal of theocentric orthodoxy in liturgical worship. A brief look at the

last 50 years in light of the early Church Fathers’ teachings provides a

surprisingly relevant breath of fresh air.

Most Catholics are all too familiar with the folk music “reforms”

to liturgical music of the 1970s and ’80s. Adopting secular music and the spirit of

the age, untutored youth began setting music to pop-style rhythms and melodies,

usually with acoustic guitar accompaniment. This style of liturgical music

became immensely popular, spread rapidly, and was taken up by prolific

composers such as Marty Haugen and David Haas. Michael Matheson Miller of the

Acton Institute refers to this liturgical Candyland as the “suburban rite.” The

problem with this music, noted by more than one critic, is that it is filled with

fuzzy doctrine and the spirit of the sexual revolution: “peace,” “love,” and

bad style.

On the other hand, many remember

the Grammy-award winning CD Chant, which hit the music market in 1994

and became an overnight sensation. Chant, sung by the Benedictine monks

of Santo Domingo de Silos, appealed to traditional Christians and New-Age

listeners alike. It was considered the perfect antidote to a stressful,

workaholic world exacerbated by paltry pop music. The perennial qualities of

plainchant became self-evident to the listener of these recordings. But for the

monks, plainchant was more than a musical expression that they appreciated and

polished like curators of a museum; it was essential to their life of prayer.

The monks explained in the jewel-case insert for Chant how they had become

physically ill, suffering fatigue and exhaustion, while experimenting with

post-Vatican II music for the Divine Office. The sentimental emotion of pop and

folk melodies was not sustainable over a seven-hour worship day.

Sacrosanctum

Concilium, the Second

Vatican Council’s Dogmatic Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, noted that, in

addition to recent pontiffs, the early Fathers of the Church also illuminate

the function of sacred music. A deeper reading of the Fathers, beloved by Pope

Emeritus Benedict, can assist us in liturgical renewal.

St. Basil

the Great and charismatic music

Far from being distant and “out

of touch,” the words of the Fathers are quite down-to-earth and often humorous.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers