Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 126

October 18, 2013

Fasting and the Call to Holiness

Fasting and the Call to Holiness | John B. Buescher | HPR

Our salvation depends wholly on God’s grace, of which we are completely undeserving. But through fasting, as well as through prayer and almsgiving, we can open up space for God’s grace to enter.

The Second Vatican Council’s document, Lumen Gentium, was

issued in 1964. Its section on “The Universal Call to Holiness,” read on

its own, is puzzling because it seems to suggest that lay Catholics had

not realized before that they, too, like the clergy, were called to

holiness. However, I’m trying to imagine who those Catholics were who

didn’t know that they were called to holiness. As far as I can remember,

Catholics well understood that the Church called everyone, everywhere,

to be holy. The section on the Universal Call to Holiness appears in Lumen Gentium’s

longer description of the hierarchical Church, and so should be read as

an effort to emphasize that the laity, too, are called to pursue

holiness as an explicit part of their vocation.

The document’s explanation of what this call to holiness for the

laity entails, practically speaking, is sketchy. The main “new” practice

that has resulted from it has been the encouragement in some quarters

for the laity to pray the Liturgy of the Hours. We are also encouraged

to attend daily Mass, and to receive Communion frequently. In this, the

laity are to take up more seriously one of the three, long-established

spiritual practices—prayer—the other two being fasting and almsgiving.

It seems doubly confusing and disconcerting that the 1964 “call to

holiness” was quickly followed in February 1966 by a revision of

Catholics’ fasting rules (in Pope Paul VI’s Apostolic Constitution, that

relaxed and, in effect, nearly eliminated the fasting and abstinence

requirements altogether.)

(See: http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/paul_vi/apost_constitutions/documents/ hf_p-vi_apc_19660217_paenitemini_en.html>Paenitemini

and in the USCCB’s: http://www.usccb.org/prayer-and-worship/liturgical-resources/lent/us-bishops-pastoral-statement-on-penance-and-abstinence.cfm Pastoral Statement on Penance and Abstinence).

To get some perspective on how lax today’s requirements are, compared

to previous times, take a look at this description of the fasting and

abstinence rules in effect in Britain in 1828, from Thomas Ignatius M.

Forster, Circle of the Seasons, and Perpetual Key to the Calendar and

Almanac:

Steve Ray blog and video: On Ferry from Italy to Patras Greece

From Steve Ray's website, Catholic-Convert.com, posted yesterday:

We

started out the day with a wonderful Mass at Lanciano where a

Eucharistic miracle happened in the 700s. We toured the museum with all

the scientific evidence people enjoyed the gift shop.

Then we were off to the port. It wasn’t a long drive but it was beautiful through the gorgeous landscape of Italy.

We had conversion stories told on the buses along the way. I told

mine on both buses and Mark Brumley shared his as well as Fr. Mark Mary

who told his vocation story.

We arrived at the dock at Ancona Italy and boarded our beautiful ferry. Everyone was surprised how nice the ferry was.

All is beautiful going along Italian coastline and into Greek

Islands. We had an hour meeting to explain procedures and also a mini

“seminar at sea”. We talked about the Battle of Lepanto between the

Christians and the Muslims because will be landing in Patras Greece

tomorrow where the battle took place.

By the way, Patras has the bones of the Apostle St. Andrew, brother

of St. Peter. And it was here that the Catholic armies won the Battle of

Lepanto against the Muslims by the power of the Rosary. If they had

lost, you would all be speaking Arabic today!

Moderate Muslim Myopia

Moderate Muslim Myopia | William Kilpatrick | CWR

Why the Western strategy of

enlisting moderate Muslims against radical Muslims isn't going well.

Here’s a question to test your

knowledge of Islam. The Muslim calendar is dated from:

a) the birth of Muhammad

b) the first revelation to Muhammad

c) the immigration of Muslims to

Medina from Mecca

d) the death of Muhammad

The correct answer is “c.” This may

come as a surprise to many Westerners, who might assume that the

birth of a religion’s founder or his first message from God would

be the most significant dates. But Muslims don’t view events

through Western eyes. The fact is, Islam was a relatively

unsuccessful religion during the first twelve years of Muhammad’s

ministry—that is, the first twelve years after the initial

revelation in 610 A.D. During that period, Muhammad never had more

than one hundred followers at one time. It was only after the move to

Medina and the commencement of raiding, looting, and warfare that

Islam began to attract sufficient followers to force the submission

of the unbelievers in Arabia.

In a

recent article for Gatestone Institute,

Salim Mansur, a professor of political science at Western University

in Ontario, draws a distinction between Islam the religion and

“Islamism,” which he describes as a totalitarian ideology

“masquerading as a religion.” Along with other moderate Muslims,

Mansur holds out the hope that Muslim societies can reform themselves

if they embrace the “faith-tradition” of Islam and reject the

“aberrant strain” of Islamism. Finally, he calls on the West to

come to the aid of anti-Islamist Muslims in their struggle against

the “perversion” of political Islam.

But, in fact, the strategy outlined by

Mansur has been in place ever since 9/11. Since that time, Western

leaders and strategists have devoted a great deal of energy to

enlisting moderate Muslims against radical Muslims. The problem is,

the strategy hasn’t worked. The Muslim world is even more

radicalized now than it was in 2001. The drawback of the approach is

that the task of separating religious Islam from political,

supremacist Islam is difficult, if not impossible. The two sides of

Islam are inextricably linked both textually and historically.

One reason—perhaps the main

reason—the Islamists have been able to convince otherwise peaceful

Muslims that militant Islam is the authentic Islam is that they have

the facts on their side.

October 17, 2013

St. Ignatius of Antioch and the Early Church

St. Ignatius of Antioch and the Early Church | Kenneth D. Whitehead | From

One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic:

The Early Church Was The Catholic Church

Sometime around the year 107 A.D., a short, sharp persecution of the

Church of Christ resulted in the arrest of the

bishop of Antioch in Syria. His name was Ignatius. According to one of

the harsh penal practices of the Roman Empire

of the day, the good bishop was condemned to be delivered

up to wild beasts in the arena in the capital city. The insatiable

public appetite for bloody spectacles meant a chronically short supply

of victims; prisoners were thus sent off to

Rome to help fill the need.

So the second bishop of Antioch was sent to Rome as a

condemned prisoner. According to Church historian Eusebius (ca. 260-ca. 340), Ignatius had been bishop in Antioch

for nearly forty years at the time of his arrest. This means

that he had been bishop there while some of the original

apostles were almost certainly still alive and preaching.

St. Ignatius of Antioch was conducted first by land from

Syria across Asia Minor (modern Turkey). He was escorted

by a detachment of Roman soldiers. In a letter he sent ahead

to the Church of Christ in Rome, this bishop described his

ardent wish to imitate the passion of Christ through his own

coming martyrdom in the Roman Colosseum. He warned

the Christians in Rome not to try to save him. He also spoke of his conflicts with his military escort and of their casual

cruelties, describing his guards as "ten leopards". The discipline of the march cannot have been unrelieved, however,

since Ignatius was permitted to receive delegations of visitors from local Churches in the cities of Asia Minor through

which the escorts and Ignatius passed along the way (To the

Romans, 5:1).

In Smyrna (modern Izmir), St. Ignatius met, not only with

the bishop of that city, St. Polycarp, but also with delegations from

the neighboring cities of Ephesus, Magnesia, and

Tralles. Each delegation was headed by a local bishop. Ignatius wrote

thank-you letters to the Christians in each of these

cities who had visited the notable but shackled bishop-prisoner. Chiefly

through these letters, St. Ignatius of Antioch is known to us today.

Establishing these letters, written in Greek, as authentic

and genuinely from the first decade of the second century

was one of the triumphs of nineteenth-century British scholarship. Without them, this bishop of Antioch might have

remained no more than a name, as obscure as many another

early Christian bishop.

Escorted on to the Greek city of Troas on the Aegean Sea,

Ignatius wrote yet another letter to the Church at Smyrna,

through which he had passed. He also wrote personally to

Bishop Polycarp of that city. Finally, from Troas he wrote

still another letter to the Philadelphians; the local Church of

Philadelphia had despatched two deacons who overtook his

party at Troas.

Shortly after writing these seven letters to Churches in

Asia Minor, St. Ignatius of Antioch was taken aboard ship.

The remainder of his journey to Italy was by sea. Tradition

holds that he won his longed-for martyrdom in the Roman

amphitheater during the reign of Emperor Trajan (98-117).

But the letters he left behind afford us a precious and remarkable picture of what that Church was like not even two

full generations after issuing from the side of Jesus Christ on

the Cross.

The adult life of St. Ignatius of Antioch as a second-generation Church leader almost exactly spanned the period

of transition between the end of the first Christian generation and the beginning of the third. Thus, his witness about

the nature of the Church of his day is of the most profound

and fundamental importance.

What was the Church like around the year 107 A.D.? The

Church had already spread far and wide since the days of the

apostles. St. Ignatius was conducted over a good part of what,

today, is Turkey, encountering local Churches in most major

towns. At the head of each of these Churches was a principal

leader, a bishop. The geographical spread of individual local

Churches, each headed by a bishop, is obvious from the fact

that Ignatius was met by delegations headed by bishops from

each sizeable town along the route.

That St. Ignatius was met by these "official" delegations

indicates that local Churches were in close touch with one

another. They did not see themselves as independent, self-selected,

self-governing congregations of like-minded people; they saw themselves

as linked together in the one body

of Christ according to an already firmly established, well-understood

system, even though they happened to be geographically separated.

The solidarity with which they all turned out to honor a prisoner being led to martyrdom, who also happened to be the

bishop of Antioch, tells us something about their respect for

the incumbent of that office. Antioch was to become one of

the great patriarchal bishoprics of the Church of antiquity, along

with Alexandria and Rome--and, later, Constantinople.

[image error]

The letters of St. Ignatius are even more pointed concerning the role that a bishop ("overseer") held in the early

Church. The modern reader may be startled at the degree to

which these letters exalt the role of the bishop. "It is essential to act in no way without the bishop", Ignatius wrote to

the Trallians. "... Obey the bishop as if he were Jesus Christ"

(2:2,1). "Do nothing apart from the bishop", he wrote to

the Philadelphians (7:2). To the Smyrnaeans, he gave the same

advice: "You should all follow the bishop as Jesus Christ did

the Father .... Nobody must do anything that has to do with

the Church without the bishop's approval" (8:1).

The New Testament shows the apostles appointing others

besides themselves to offices in the Church. Peter and the

other apostles at Jerusalem very quickly decided to appoint

deacons to assist them (cf. Acts 6: 1-6). Paul similarly placed

someone in authority in the Churches he founded (cf. Acts

14:23; 2 Tim 1:6). These ecclesiastical appointments were

carried out by means of a religious rite: the laying on of

hands, either by those who already had authority conferred

on them by Christ (the apostles) or those on whom they had

conferred authority by the laying on of hands. These rites

were sacramental ordinations.

For a period of time in the early Church there seems to

have been no entirely clear terminology designating these

ordained Church officers or ministers. St. Paul spoke of bishops and deacons (Phil 1:1), though he also mentions other

offices, such as apostles, prophets, and teachers (1 Cor 12:29).

St. James spoke of elders (5:14). In the Acts of the Apostles

(e.g., 11: 30), we hear many times of elders or presbyters. Sometimes the designations bishop and elder seem to have been

used interchangeably.

In the course of the second half of the first century, however, a

consistent terminology for these Church offices was becoming fixed. The

letters of St. Ignatius of Antioch make

clear that leadership in the Christian community, in all the

Churches, is exercised by an order of "bishops, presbyters,

and deacons" (To the Trallians 3:2; To Polycarp 6:1). Of these

designations, bishop comes from the Greek episkopos, meaning "overseer"; presbyter from the Greek presbyteros, "elder";

and deacon from the Greek diakonos, "servant" or "minister".

Thus, from that time on, these were the offices in what

was already an institutional, hierarchical Church (this is not

to imply that the Church was ever anything but institutional

and hierarchical, only that the evidence for these characteristics had become unmistakably clear by this time).

By the way, the term priest (Greek: hierus) does not seem

to have been used at first for the Christian presbyter; the

nonuse of this particular term in the earliest years of the

Church was due to the need to distinguish the Christian

priesthood of the new dispensation from the Jewish Temple

priests, who were still functioning up to the time of the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple by the Romans in the

year 70 A.D. After that time, the use of the word priest for

those ordained in Christ began to be more and more common.

St. Ignatius of Antioch did not know of any such thing as

a "Church" that was merely an assemblage of like-minded

people who believed themselves to have been moved by the

Spirit. The early Christians were moved by the Spirit to join

the Church, the established visible, institutional, sacerdotal,

and hierarchical Church-the only kind St. Ignatius of Antioch would ever have recognized as the Church.

And it was for this visible, institutional, sacerdotal, and

hierarchical Church--an entity purveying both the word and

sacraments of Jesus--that this early bishop was willing to give

himself up to be torn apart by wild beasts in the arena. He

wrote to St. Polycarp words that were also meant for the latter's flock in Smyrna: "Pay attention to the bishop so that

God will pay attention to you. I give my life as a sacrifice

(poor as it is) for those who are obedient to the bishop, the

presbyters, and the deacons" (6:1). To the Trallians he wrote:

"You cannot have a Church without these" (3:2).

St. Ignatius certainly did not fail to recognize that, in one

of today's popular but imprecise formulations, "the people

are the Church." His letters were intended to teach, admonish, exhort,

and encourage none other than "the people".

But he also understood that each one of "the people" entered the Church

through a sacred rite of baptism, and thereafter belonged to a group in

which the bishop, in certain

respects and for certain purposes, resembled, on the one hand,

the father of a family and, on the other, a monarch--more

than some democratically elected leaders.

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles, Book Excerpts, and Interviews:

• Selections from Jesus, The Apostles, and the

Early Church | Pope Benedict XVI

• A Short Guide to Ancient Heresies | Kenneth D. Whitehead

• Studying The Early Christians: The Introduction to We Look For

the Kingdom | Carl J. Sommer

• The Everyday Lives of the Early Christians | An interview with Carl J. Sommer

• Church and State in Early Christianity | Hugo Rahner, S.J.

• His Story and the History of the Church | An Interview with Dr. Glenn W. Olsen

• Are We at The End or The Beginning? | Dr. Glenn Olson

• Who Is A Priest? | Fr. Benedict Ashley, O.P.

• The Church Is the Goal of All Things | Christoph Cardinal Schönborn

• St. Peter and the Primacy of Rome | Stephen K. Ray

• Church Authority and the Petrine Element | Hans Urs von Balthasar

Kenneth D. Whitehead is a former U.S. Assistant Secretary of Education.

He has authored or coauthored several books, as well as many articles for

leading Catholic periodicals, and is the translator of some twenty published

books.

Toward a More Human State of Economics

Toward a More Human State

of Economics |

Br. Gabriel Torretta, OP | Catholic World Report

Maciej Zięba's book,

Papal Economics

, offers the right questions (and

some good answers) about Catholic social thought

When Pope Francis was first

elected on March 13 of this year, some of the early media reports

about the largely unknown Argentine cardinal painted a dire portrait

of a man with shadowy connections to a military dictatorship, a man

whom rumor described as conspicuously silent during the

government-sponsored murder of priests preaching liberation theology.

But in recent days, in the wake of the compelling interviews with

America and La Reppublica, many of these same voices

have discovered a new Pope Francis, one who is tolerant, open-minded,

anti-establishment, and perhaps even supportive of some forms of the

liberation theology he was once accused of persecuting.

Readers of papal encyclicals

on politics and economics, broadly called Catholic social thought,

often walk away with a similarly double image: commentators on John

XXIII’s Mater et Magistra, John Paul II’s Centesimus

Annus, and Benedict XVI’s Caritas in Veritate have

claimed and counter-claimed each document as a certain and final

victory for democratic capitalism or state-run socialism, depending

on the commentator’s predilections.

Asking the Right

Questions

All too often, questions

about the Church’s politics end up like the trompe-l’oeil

images that vex freshman philosophy students. Is it a duck or a

rabbit? An old lady or a young girl? Is Pope Francis a fascist or a

Marxist? Is Catholic social thought capitalist or socialist? Is it

all in the eye of the beholder?

These questions do not have

a satisfying answer because they are the wrong questions.

October 16, 2013

The Arts—Agents of Change and Source of Enchantment

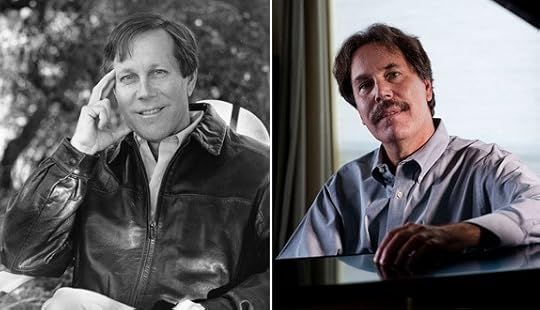

The Arts—Agents of Change and Source of Enchantment | Carl E. Olson | CWR

Dana and Ted Gioia discuss literature, music, education, business, culture, and the Catholic Faith.

Dana

and Ted Gioia (pronounced JOY-uh) are authors,

musicians, composers, critics, educators, and businessmen. They are also

brothers, born and raised in Hawthorne, California, in an Italian-Mexican,

Catholic family. Although both have been interviewed numerous times over the

years, this marks the first time they have been interviewed together, answering

the same questions.

Dana

Gioia (www.DanaGioia.net),

the eldest, is an internationally acclaimed and

award-winning poet, and the former Chairman of the National Endowment for the

Arts. He received a BA and an MBA from Stanford University and an M.A. in

Comparative Literature from Harvard University. He has published four

full-length collections of poetry (and several shorter collections), and the

collection Interrogations at Noon won the 2002 American Book Award. His poetry has also appeared in

numerous anthologies. His 1991 book, Can

Poetry Matter?, was a finalist for the National Book Critics

Circle award. His poems, translations, essays, and reviews have appeared in

many magazines, including The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The Washington Post Book World, The New York Times Book

Review, Slate, and The Hudson Review. Dana has written three opera libretti

and is an active translator of poetry from Latin, Italian, and German. Renominated

in November 2006 for a second term and once again unanimously confirmed by the

US Senate, he was the ninth Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts. He

left his position as Chairman in 2009, and in 2011 he became the Judge Widney

Professor of Poetry and Public Culture at the University of Southern California,

where he teaches each fall semester. He is also a member of the College of

Fellows at the Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology (Berkeley). Dana has

been the recipient of ten honorary degrees and has won numerous awards,

including the 2010 Laetare Medal from Notre Dame. He and his wife, Mary, have

two sons, and he divides his time between Los Angeles and Sonoma County,

California.

Ted Gioia (www.TedGioia.com), seven years younger than Dana, has published eight non-fiction

books, most recently the bestselling The Jazz

Standards: A Guide to the Repertoire. His book The History of Jazz was selected as one of the twenty best books of the year in 1997

by Jonathan Yardley in The Washington

Post, and was chosen as a notable book of the year in The New York Times. His 2008 book Delta Blues was also selected by The New York Times as one of the 100 most notable of the year, and

was picked as one of the best books of the year by The Economist. In 2006, Ted published two books simultaneously, Work Songs and Healing Songs, and both were honored with a special ASCAP-Deems

Taylor Award. His 2009 book, The Birth

(and the Death) of Cool, was a work of cultural criticism and a historical

survey of hipness, and his concept of post-cool,

outlined in this work, was highlighted as one of the “ideas of the year” by Adbusters. Ted’s writings have appeared

in The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, Salon, American Scholar, Hudson Review, and the San Francisco Chronicle, among other

publications. Ted received a degree in English at Stanford (graduating with

honors and distinction), served as editor of Stanford’s literary magazine, Sequoia. He also worked extensively as a

jazz pianist during that time, and designed and taught a class on jazz at

Stanford while still an undergraduate. After graduation, Gioia received a

degree in philosophy, politics, and economics at Oxford University, where he

graduated with first class honors. He then received an MBA from Stanford

University. Ted has also consulted to Fortune 500 companies, and has undertaken

business projects in numerous countries on five continents. In the 1980s he

established a formal jazz studies program at Stanford, and served on the

faculty alongside artist-in-residence Stan Getz for several years. His first

book, The Imperfect Art, published in 1988, was

awarded the ASCAP-Deems Taylor award and was named a “Jazz Book of the Century”

by Jazz Educators Journal. Ted has

recorded several jazz albums, including The End of the Open Road, Tango Cool, and The City is a Chinese Vase.

Carl E. Olson, editor of CWR, interviewed Dana and Ted over the

past couple of months, asking each the same questions about their childhood,

their faith, literature and music, education, American culture, and the role of

the Church in supporting the arts.

CWR: Is it accurate to say

that two influences profoundly shaped your childhood years: your family’s

Catholic faith and your uncle, Ted, who died before you had a chance to know

him? What role did each play in your intellectual and cultural formation? What

other influences are noteworthy?

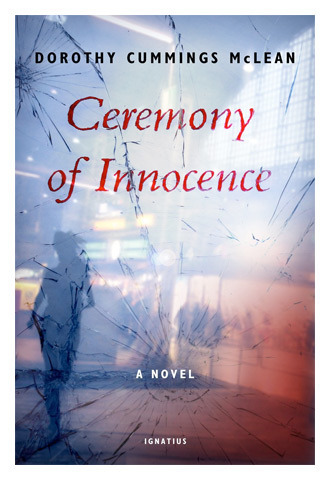

An Interview with novelist Dorothy Cummings McLean

by John Herried | IPNovels.com

We sit down with the author of the new Ignatius novel Ceremony of Innocence, Dorothy Cummings McLean. A Canadian writer living abroad, she has been a regular contributor to The Catholic Register (Toronto). Her first book, Seraphic Singles, is a popular work of nonfiction. Until Wednesday, Ceremony of Innocence is also featured in our novel sale.

Ceremony of Innocence owes a debt to Graham Greene’s The Quiet American. Did Greene’s novel inspire you to write yours?

My novel is both a tribute and a parody to Greene’s novel. It’s a

tribute to Greene’s amazing gifts as a storyteller and a parody of

“Greeneland” in that it turns various elements of The Quiet American on their heads.

You have lived in Europe for many years. How have your experiences informed the story?

I didn’t move to Europe until after I had written the novel. However,

the themes and setting of the novel spring from the summer I studied in

Germany. I spent most of my time in Frankfurt-am-Main. I loved this

city. It was energetic, cosmopolitan, and strangely beautiful. While I

was writing, I would trace my characters’ peregrinations along a

Frankfurt city map.

It was a lucky summer to be in Frankfurt because Germany was hosting

the FIFA World Cup, and the German team exceeded all expectations.

Suddenly it was as if the Germans had decided to be proud of Germany.

Normally the Germans around me, even 22-year-old seminarians, acted as

if Germany had the mark of Cain on its collective forehead. They

complained about Germany endlessly, but heaven help you if you agreed. I

was careful never to mention the last war—but they all did. My German

friends call the Hitler years the national trauma.

The summer was lucky in other ways. While I was there, news broke

that a gang of young Islamists had been arrested for planning terrorist

attacks in my hometown of Toronto. I was beside myself with rage but

also deeply thankful no one had been hurt. And a month later, news broke

that two young Islamists had been arrested for planting bombs on trains

leaving Cologne. The bombs had been left two days after I had visited

Cologne—by train. They were foreign students and, as a fellow foreign

student, I was disgusted.

In Joseph Ratzinger’s (Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI) book A Turning Point for Europe?

he declares that the term “fundamentalist”, primarily associated with

American Protestantism, does not really apply to current Islamist

radicals, instead pointing to a fusion of Marxist and Islamic theories

of liberation as being the undercurrent driving Islamist terrorism. So,

despite being used as a weapon against the West, this form of terrorism

has some roots in Western ideologies. Does this attraction to a kind of

Marxist “liberation” play a part in the plot? Does it explain why a

Westerner might be attracted to Islamist radicalism?

I think Westerners are attracted to Islamist radicalism because, to

be blunt, they think it is sexy. It is strong, it is well-funded, it is

exotic, and it claims to fight for the underdog. It also aligns itself

with the religion of Islam, which is itself culturally strong and,

thanks to the jaded Western palate, appeals to Orientalist sexual

fantasies of masculine domination and feminine submission.

By contrast, Western culture divorced from Christianity and its own

past is pallid, shallow, consumerist, and even distasteful, and that is

the culture most Westerners of the post-Vatican II, post–mainstream

Protestant era have grown up in. Unfortunately, millions of Europeans

and Americans have been indoctrinated by the culture to believe that the

Christianity of their ancestors is uncool and therefore bad. The

victory of the counter-culture has also given rise to North America’s

fratricidal culture wars and, where Islamism is concerned, “the enemy of

my enemy is my friend.”

I am certainly concerned by what Western teenagers, especially in the

English-speaking world, are taught about their ancestors and the

histories of their countries or, rather, what effect it has on the

teenagers. If the teenagers feel inspired to make their countries better

places to live, good. If the teenagers despair and think Al Qaeda is

justified, bad.

Meanwhile, I am very concerned about idealistic teenagers being

sucked into causes by manipulative adults, no matter what the cause.

Despite the serious nature of the issues explored in Ceremony of Innocence, there is also a great deal of humor—much of it laced with irony. How does humor assist in storytelling?

October 15, 2013

St. Teresa of Avila, "a woman extraordinarily gifted, both naturally and supernaturally."

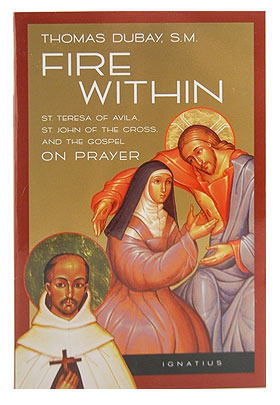

A couple of excerpts from  Fire Within: St. Teresa of Avila, St. John of the Cross, and the Gospel--On Prayer, the late Fr. Dubay's outstanding study on prayer:

Fire Within: St. Teresa of Avila, St. John of the Cross, and the Gospel--On Prayer, the late Fr. Dubay's outstanding study on prayer:

By all accounts, St. Teresa, the

foundress from Avila, was a woman extraordinarily gifted, both naturally

and supernaturally. In her were combined physical beauty, especially in

her youth, and a charm of personality that neither illness nor age

diminished. All witnesses seem to agree that she was the type of woman

no one can adequately describe in a few pages. She was one of those rare

personalities who combine qualities that seem to exclude one another

and are seldom found together in one individual. She loved tenderly and

affectionately, yet would brook no nonsense from anyone. She possessed

both a strong self-image and an astonishing humility. A born leader, she

was yet completely obedient to her superiors. She could be a windmill

of activity at one time and at another be lost in mystical

contemplation. Though she was highly intelligent and amazingly

efficient, she gravitated toward simple, humble men and women. (pp.

14-15)

Regarding a woman of prayer and penance

who came to visit her, Teresa remarks that "she was so far ahead of me

in serving the Lord that I was ashamed to stand in her presence", and

she says of the nuns with whom she lived in her first reformed convent

that "this house was a paradise of delight for Him. ... I live in their

company very, very much ashamed." She was of the opinion that she

deserved to be persecuted, and she welcomed even untrue accusations

against herself. Foundress though she was, Teresa must have been known

widly for choosing to do menial tasks, for that trait comes up more than

once in the depositions of her process.

In the very nature of things there is an

intimate connection between humility and obedience, and while I am

omitting in this sketch many of St. Teresa's heroic virtues, I feel that

the latter should be joined to the former. To appreciate both of these

virtues in her, we need to recall that she was anything but a timid,

passive individual. Diffident people often do not find it difficult to

acquiesce to another's decisions either because they are reluctant to

assume responsibility for important decisions or because they fear

failure and criticism. But as we have noted, Teresa was of an entirely

cast of mind: she was full of ideas and abounding in initiative and

determination. Criticism bothered her not in the least. Being a born

leader, she must have found submitting to another's will naturally

irksome. Yet her obedience was legendary. We cannot here detail the many

examples of the prompt, joyful carrying out of difficult directions

that she must have found extremely painful to her buoyant determination.

What she taught, she lived. (p. 27)

And here are some quotes from St. Teresa of Avila (1515-1582), the great

Carmelite contemplative, mystic, Saint, and Doctor of the Church, whose

feast is celebrated today:

• "There is no stage of prayer so sublime that it isn't

necessary to return often to the beginning. Along this path of prayer,

self knowledge and the thought of one's sins is the bread with which

all palates must be fed no matter how delicate they may be; they cannot

be sustained without this bread."

• "It is a dangerous thing to be satisfied with ourselves."

• "Do not be negligent about showing gratitude."

• "Those who in fact risk all for God will find that they have both lost all and gained all."

•

"We shouldn't care at all about not having devotion—as I have said—but

we ought to thank the Lord who allows us to be desirous of pleasing

Him, even though our works may be weak. This method of keeping Christ

present with us is beneficial in all stages and is a very safe means of

advancing."

• "Everything other than pleasing God is nothing."

• "Our security lies in obedience and refusal to deviate from God's law."

•

"Once you are placed in so high a degree as to desire to commune in

solitude with God and abandon the pastimes of the world, the most has

been done."

• "Teach by works more than by words. ... We must all try to be preachers through our deeds."

•

"Mental prayer in my opinion is nothing else than an intimate sharing

between friends; it means taking time frequently to be alone with Him

who we know loves us. In order than love be true and friendship endure,

the wills of the friends must be in accord."

• "I don't know why

we are amazed that there are so many evils in the Church since those

who are to be the models from which all might copy the virtues are so

obscurely fashioned that the spirit of the saints of the past has

abandoned the religious communities. May it please the divine Majesty to

remedy this as He sees it to be necessary."

• "Now, Lord, now; make the sea calm! May this ship, which is the Church, not always have to journey in a tempest like this."

Those are from the fourth volume of Sermon in a Sentence: A Treasury of Quotations on the Spiritual Life, a series (five, so far) of books featuring quotes from St. Thérèse of Lisieux (vol. 1), St. Francis de Sales (vol. 2), St. Catherine of Siena (vol. 3), and St. Thomas Aquinas (vol. 5). The books are edited and arranged by John P. McClernon, who also writes bios of the saints for each book.

On February 2, 2011, Pope Benedict XVI devoted his General Audience to St. Teresa, saying:

It is far from easy to sum up in a

few words Teresa’s profound and articulate spirituality. I would like

to mention a few essential points. In the first place St Teresa

proposes the evangelical virtues as the basis of all Christian and

human life and in particular, detachment from possessions, that is,

evangelical poverty, and this concerns all of us; love for one another

as an essential element of community and social life; humility as love

for the truth; determination as a fruit of Christian daring;

theological hope, which she describes as the thirst for living water.

Then we should not forget the human virtues: affability, truthfulness,

modesty, courtesy, cheerfulness, culture.

Secondly, St Teresa proposes a profound harmony with the great

biblical figures and eager listening to the word of God. She feels

above all closely in tune with the Bride in the Song of Songs and with

the Apostle Paul, as well as with Christ in the Passion and with Jesus

in the Eucharist. The Saint then stresses how essential prayer is.

Praying, she says, “means being on terms of friendship with God

frequently conversing in secret with him who, we know, loves us” (Vida

8, 5). St Teresa’s idea coincides with Thomas Aquinas’ definition of

theological charity as “amicitia quaedam hominis ad Deum”, a type of

human friendship with God, who offered humanity his friendship first; it

is from God that the initiative comes (cf. Summa Theologiae II-II, 23, 1).

Prayer is life and develops gradually, in pace with the growth of

Christian life: it begins with vocal prayer, passes through

interiorization by means of meditation and recollection, until it

attains the union of love with Christ and with the Holy Trinity.

Obviously, in the development of prayer climbing to the highest steps

does not mean abandoning the previous type of prayer. Rather, it is a

gradual deepening of the relationship with God that envelops the whole

of life.

Rather than a pedagogy Teresa’s is a true “mystagogy” of prayer: she

teaches those who read her works how to pray by praying with them.

Indeed, she often interrupts her account or exposition with a prayerful

outburst.

Here are some of the resources from Ignatius Press relating to St. Teresa of Avila:

• Fire Within: Teresa of Avila, John of the Cross and the Gospel on Prayer, by Fr. Thomas Dubay, S.M.

• Drink of the Stream: Prayers of Carmelites , compiled by Penny Hickey

• Teresa of Avila: Personality and Prayer , a DVD series by Fr. Dubay

• St. Teresa of Avila , an ambitious mini-series shot in Spain

Gripping, debut novel tackles political and social issues at the root of the decline of Europe

SAN FRANCISCO, October 15, 2013 – Riots, terrorist attacks, and neo-Nazi

violence take center stage in the debut novel Ceremony of Innocence by Dorothy Cummings

McClean.

Ceremony of Innocence is set in modern-day Germany, where journalist

Catriona McClelland has seen it all while covering the contemporary European scene for a Catholic

news organization. Keeping herself above the political fray in her professional life, she has also

managed to keep herself from personal entanglements. Things come to a head when her boyfriend

Dennis, frustrated with a lack of commitment, leaves her for Suzy Davis, an idealistic young

Canadian who is involved with a left-wing protest movement. But when Suzy is murdered . . . who is

complicit and who is innocent?

Ripped from the headlines, Ceremony of

Innocence is a very contemporary novel of Europe on the edge of social breakdown. Train stations

are bombed and migrants targeted for violence as journalists and other tastemakers watch from their

positions of privilege.

Dorothy Cummings McLean’s realistic narrative does not describe the

feats of heroes. Rather, it unnervingly lays bare the way religious faith and moral reasoning can be

easily manipulated and compromised.

Piers Paul Read, the author of Alive: The

Story of the Andes Survivors, praises Ceremony of Innocence, saying, “I highly recommend

this enjoyable, interesting and well-written novel that gives rare insight into present-day

Germany.”

Ceremony of Innocence is “[a] true joy to read. In a literary world

increasingly distended with stale predictability, it’s so energizing to read something genuinely

original and vibrant,” says Michael Coren, TV Host and author of Heresy: Ten Lies They

Spread About Christianity.

Richard Greene, Ph.D., Professor of English,

University of Toronto, calls it “[a]n exciting debut novel. It is well-paced, intelligent, and

suspenseful. In the style of Graham Greene, Dorothy Cummings McLean has placed her characters on the

knife-edge between terror and salvation.”

Ceremony of Innocence is “[a] terrifying

voyage into a sinister underworld of political extremism and spiritual confusion. It is replete with

dark secrets, betrayals and above all, damaged young people struggling to find a sense of purpose

amid the moral chaos of near-contemporary Europe. The novel’s stunning climax will leave the reader

reeling with shock,” says Fiorella De Maria, author of Poor Banished Children.

“Dorothy Cummings McLean opens a disturbing window into a parallel world where twenty-first

century Catholics walk the line between the ceremony and the reality of innocence. Amidst hedonism,

Neo-Nazism, banal leftism and militant Islam lurk murder and treachery with only the merest hint of

redemption. Bewildering and exhilarating by turns,” says Alan Fimister, Ph.D., International

Theological Institute.

Stuart Reid, former editor of The Spectator, says Ceremony

of Innocence is “[a] fast-paced thriller in which Terrorist International wages war against

Europe, America and Christian civilization. All human life is here – drugs and degenerate music;

neo-Nazis, enigmatic spooks and terrified Muslim immigrants; bombs, quarrelling lovers and scheming

Eurotrash – and, underpinning everything is sorrow, contrition and hope.”

Dorothy Cummings McLean is a Canadian writer living abroad. She has been a

regular contributor to The Catholic Register (Toronto). Her first book, Seraphic Singles:

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Single Life, is a popular work of nonfiction.

Dorothy Cummings McLean is available for interviews about this book.

To request a review copy or an

interview with Dorothy Cummings McLean please contact:

Rose Trabbic, Publicist, Ignatius Press

at (239)867-4180 or rose@ignatius.com

Product Facts:

Title: CEREMONY OF INNOCENCE

A Novel

Author: Dorothy Cummings McLean

Release

Date: October 2013

Length: 189 pages

Price: $19.95

ISBN: 978-1-58617-731-7 •

Hardcover

Order: 1-800-651-1531 • www.ignatius.com

Evangelical theologian lauds "Christocentric legacy" of Benedict XVI

by Carl E. Olson | CWR Blog

Although he might not be well known outside of certain theological circles, Dr. Hans Boersma is one of the finer young Evangelical theologians writing today. He is the J.I. Packer Professor of Theology

at Regent College, one of the best Evangelical schools in Canada, and he is the author of some books that engage deeply and thoughtfully with Catholic theology, notably Nouvelle Théologie and Sacramental Ontology: A Return to Mystery (Oxford, 2009), and Heavenly Participation: The Weaving of a Sacramental Tapestry (Eerdmans 2011). As his bio on the Regent website states, Boersma's "main theological interests are Catholic thought, the church fathers, and spiritual interpretation of Scripture." (And in the words of a snide Amazon.com reviewer, he is "A Roman Catholic in evangelical clothing".)

In the September/October 2013 edition of Books & Culture: A Christian Review, in an article titled, "The Real Presence of Hope & Love" (subscription required for full article), Boersma praises the "Christocentric legacy" of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI and touches on how it should help fruitful ecumenical conversation between Catholics and Evangelicals. He notes that far too many discussions of theology begin with premises about "conversative" and "liberal," which often derail matters before anything of substance is actually discussed. "With regard to Benedict," writes Boersma, "what stands out is not his alleged 'conservatism' but his focus on Christ in matters both theological and moral. That is what will render him relevant for many years to come." He then writes:

Protestants have long been afraid that Catholics take their starting-point in human realties. Human merit before God, Mary and the saints as objects of our adoration, the concrete materiality of Baptism and Eucharist—these, and other aspects of Catholic theology and spirituality, seem to Protestants attempts to place ourselves in the position of the risen Lord, as a move from Christocentrism to anthropocentrism. Oakes' insistence, therefore, that Ratzinger's theology is marked first and foremost by its Christocentrism, should make Protestants sit up and listen. And I think there is a sense in which it should make both Protestants and Catholics sit up and listen. If, after all, [Fr. Edward] Oakes is right that Christocentrism lies at the heart of Ratzinger's thought, then this is the key also to how we can deconstruct the relativism of our culture that thinks only in terms of the binaries of "conservative" and "progressive." To place Christ at the center is to gainsay the need to be "up-to-date" or "relevant." To place Christ at the center is, therefore, also to stab at the heart of the relativism that underlies this division between "conservative" and "progressive." There is good reason, I think, why Ratzinger's most stringent rejection of relativism comes under the title of Dominus Iesus (2000). It is the Lord Jesus who sent us on a mission in the world, and it is his Lordship and the definitive character of his revelation that are " 'the true lodestar' in history for all humanity," as the document's concluding paragraph puts it. Evangelicals and Catholics should be drawn together by this theological—that is to say, Christological—focus, which is the real antidote to so much non-theological humbug that typifies most media interest in Catholic thought and in the Christian faith in general. The insistence that Christ is the beginning, the center, and the end of theology has always served as reminder that in terms of theology and morality there is something more important to worry about than God's relevance to us, namely, our relevance to God.

Beorsma then focuses on Benedict's first two encyclicals—Deus caritas est (2005) and Spe salvi (2007)—highlighting "Benedict's insistence that the love of God has become incarnate:

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers