Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 121

November 22, 2013

The Relevance and Challenge of C. S. Lewis

The Relevance and Challenge of C. S. Lewis | Mark Brumley

(Note: This essay originally appeared on IgnatiusInsight.com in November 2005.)

Mere Christianity sat innocently on the bookrack at a neighborhood bookstore, right next to end times prognosticator Hal Lindsey’s The Late Great Planet Earth. The author of Mere Christianity, C. S. Lewis, was unknown to me. I confused him with Lewis Carroll of Alice in Wonderland fame. What could a weaver of children’s tales teach me about Christ?

An odd question, given that Jesus himself said that we must become as little children to enter the kingdom of God. Ironic, in another way, too. For Lewis was, unbeknownst to me, renowned for a series of extraordinary children’s books, The Chronicles of Narnia. And he was a great friend of Lord of the Rings creator, J.R.R. Tolkien.

The back cover of the slim, powder blue paperback reported that Lewis had been a Cambridge professor of Medieval and Renaissance literature. Strange, I thought, that a high-brow English scholar would have written a book the publisher so assertively subtitled "What One Must Believe in Order to Be a Christian." (Newer editions of the book removed the subtitle.) Thumbing through the book, I was instantly captured by its obvious Christ-centeredness and clarity.

Lewis quickly became my best friend, theologically speaking. He challenged me to use my mind to understand Christ and his truth, to know what I believed and why I believed it. I devoured everything of his I could get my hands on. Even scholarly essays of literary criticism did not lessen my capacity for Lewisian cuisine, not even his magisterial contribution to the massive OHEL (The Oxford History of English Literature), titled English Literature in the Sixteenth Century, Excluding Drama–a repast hardly digestible by the sophomore public high school student I was at the time.

More remarkable still is that, humanly speaking, it is largely due to Lewis, an Anglican, that I converted to the Catholic Church, something as nearly inconceivable to me in my Fundamentalist days as becoming a Martian. Now, after more than two decades in the Church, I have met or learned of scores of far more illustrious Catholic converts who likewise list Lewis on their spiritual resumes. The late Sheldon Vanauken, friend of Lewis and former Anglican, once spoke of his mentor as "Moses"–one who led the way into the promised land of the Catholic Church yet never entered himself. Even Walter Hooper, faithful secretary of Lewis in his last days, executor of the Lewis estate and an erstwhile Anglican clergyman, made the pilgrimage from Canterbury to Rome. But more in a moment on Lewis’ Catholic converts and his own failure to "pope".

Interest in Lewis is on the upswing, again, especially with the Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe movie and portents of many more in a series of Chronicles of Narnia feature films. What, then, to make of this highly influential, Belfast-born Christian thinker and writer, and his impact on modern Christianity?

Apologetics and Fiction

To state the obvious: Lewis’ appeal if multifaceted. Reading him, both left and right hemispheres of the brain are fully engaged. He was, on the one hand, a fiercely logical and rigorous thinker, who cut through fallacies like a chain saw through whipped cream. His apologetics works such as The Problem of Pain, Miracles, The Abolition of Man, and Mere Christianity, all manifest a keen mind eager to grapple with the deepest problems of human experience. He is the thinking man’s Christian, or as Anthony Burgess’s widely quoted New York Times book review blurb has it, "Lewis is the ideal persuader for the half-convinced, for the good man who would like to be a Christian but finds his intellect getting in the way." (Those who would seek a summary of Lewis’ apologetics, would do well to consult Richard Purtill’s C.S. Lewis’ Case for the Christian Faith [Ignatius Press, 2004].)

Meanwhile, Lewis was also at home in the creative realm of imagination. His Chronicles of Narnia and his "space trilogy" still rank among the bestsellers of fantasy literature; his novel Till We Have Faces, a retelling of the Psyche myth, provides a sublime and penetrating insight into the human heart, including its power of self-deception. We can’t mention all of Lewis’ work, of course, but we shouldn’t neglect what was probably, until recently, Lewis’ greatest fictional "hit," The Screwtape Letters, the humorous and spiritually perspicacious depiction of a senior tempter, Screwtape, and his efforts to train his wet-behind-the-ears nephew and junior temper, Wormwood.

With respect to Christian faith, Lewis remains a "draw" because he took Christianity seriously. Christianity was a matter of capital "T" Truth, for Lewis, and such Truth always has consequences. God is real, Christ is real, and the Christian faith is real. Their reality is not trivial, but cosmos-shaking and massive. Christianity must matter to anyone who bothers to look at it with care. As Lewis once told a group of Welsh clergymen, in a talk on Christian apologetics: "Christianity is a statement which, if false, is of no importance, and if true, of infinite importance. The one thing is cannot be is moderately important."

Lewis understood the skeptical and unbelieving mind, having once been both skeptic and unbeliever himself. He knew how to reach such a mind because he knew the honest questions such a mind poses to itself and the dishonest dodges to which it can be tempted. In a characteristically direct essay, "Man or Rabbit?," he wrote:

"Honest rejection of Christ, however mistaken, will be forgiven and healed–‘Whosoever shall speak a word against the Son of Man, it shall be forgiven him.’ But to evade the Son of Man, to look the other way, to pretend you haven’t noticed, to become suddenly absorbed in something on the other side of the street, to leave the receiver off the telephone because it might be he who was ringing up, to leave unopened letters in a strange handwriting because they might be from him–this is a different matter. You may not be certain yet whether you ought to be a Christian, but you know you ought to be a Man, not an ostrich, hiding its head in the sand."

Note the tone of familiarity, as if to say, "I know you; we are alike," and a direct moral challenge, "You may not be certain whether you ought to be a Christian, but you know you ought to be a man." Lewis was master of this style, the informal and direct moral engagement. He often applied it self-deprecatingly to himself as much as to his readers.

No Faith-Free Substitute

Another reason for Lewis’ potency: he was no innovator. He presented Christ and Christianity, not Lewis and Lewisianity. The publisher of that paperback edition of Mere Christianity that I mentioned at the outset got it only half right when on the back cover Lewis was dubbed, "The most original Christian writer of our century." I say "half right" because insofar as Lewis was a superb stylist who incarnated the Christian vision in fiction as well as essay, not to mention a uniquely effective theological popularizer, he was indeed "original." But he was not "original" in the sense of concocting his own theological synthesis or customizing his own creed. "We are to defend Christianity itself," he told the Welsh clergymen in his talk on Christian apologetics, "the faith preached by the Apostles, attested by the martyrs, embodied in the Creeds, expounded by the Fathers. This must be clearly distinguished from the whole of what any one of us may think about God and Man … as apologists … we are defending Christianity, not ‘my religion’."

Nor did Lewis regard himself as a theologian in any proper sense of the term. Whenever a finer point of theology arose, he directed people to the "real theologians." His job, as he saw it, was to be a faithful and fluent translator of the historic Christian message into the vernacular of present, not someone out to revise the message.

For Lewis, fidelity to Christ and his gospel includes not diminishing it by mixing it with unbelief. He was an inveterate opponent of what is sometimes called "liberal" or "modernist" Christianity, or as he dubbed it, "Christianity and water." This was "Christianity" with all the supernatural aspects removed or downplayed. According to Lewis, the issue was, plainly and simply, a matter of honesty. People expected a bottle labeled "Christianity" to contain Christianity, not a faith-free substitute.

But fidelity to the Faith, though necessary, is not sufficient. Lewis also felt called to fluency in it so he could more easily translate it into the modern parlance. He insisted that Christians learn to speak to modern man in terms he can understand, without tailoring the message to suit the tastes either of the hearer or of the messenger. In a rejoinder to "liberal" theologian Norman Pittenger, Lewis wrote:

"When I began, Christianity came before the great mass of my unbelieving fellow countrymen either in the highly emotional form offered by revivalists or in the unintelligible language of the highly cultured clergymen. Most men were reached by neither. My task was therefore simply the of a translator–one turning Christian doctrine, or what he believed to be such, into the vernacular, into language that unscholarly people would attend to and could understand."

Yet another reason for Lewis’s success: his "mere Christianity" was solidly ecumenical. That is, it represented a reliable core of common Christian affirmations, which Baptists, Lutherans, Presbyterians, Anglicans, and Catholics generally all acknowledge. This was not some diluted "common ground" or "least common denominator" religion. Forcefully, Lewis insisted that "mere Christianity" is "no insipid interdenominational transparency, but something positive, self-consistent, and inexhaustible."

From the Catholic perspective, that statement requires some careful qualification before it can be energetically assented to. In fact, there are some notable theological limitations to Lewis’s "mere Christianity." Yet these are not as great as its benefits, which include diminishing the denominational rancor among followers of Christ and promoting the cause of Christ in united mission before the unbelieving world.

Moreover, Lewis’s distinction between the Christian faith as such and any particular denominational formulation of it, whether Protestant or Catholic or Orthodox, has helped foster a more sympathetic assessment of Catholicism among some Protestants and, ironically, has aided in bringing more than a few searching sheep into the Catholic fold. Protestants who tend to equate Christianity with their Protestant version of it will find in Lewis no ally.

From "Mere" To "More"

Which brings us back to Lewis and Catholicism. It is a curious phenomenon, demanding explanation, that so many people influenced by Lewis, including some significant Christian thinkers and writers in their own right, have embraced more than "mere Christianity"; they have become Catholics, often crediting Lewis with helping them to cross the threshold. Why has Lewis been such an effective apologist for Catholic Christianity, given that he never became a Catholic? What of Lewis’s own position vis-à-vis the Catholic Church?

The latter question was well explored by Christopher Derrick, a long-time friend and former student of Lewis, in his book C. S. Lewis and the Church of Rome (Ignatius Press, 1981). Derrick, a Catholic, held that Lewis’s Ulster Protestant background, combined with certain quirks of Lewis’s mind, made it difficult for him to see the Catholic Church as "the Church" or the fullest embodiment of Christian truth. Joseph Pearce, in his C. S. Lewis and the Catholic Church (Ignatius, 2003), echoes the point, although less polemically and in a more wide-ranging, nuanced study.

But what Lewis himself could not see in the Catholic Church, others standing upon his broad Christian shoulders, have seen. Hence the steady stream of converts Lewis has helped come into the Catholic fold. Or, to put it in terms more in keeping with Vatican II’s language, into full communion with the Catholic Church. In that respect, Lewis has been called a "Church Uncle," rather than a Church Father.

Surveying Lewis’ writings, a strong case can be made that he imbibed a significant amount of distinctively Catholic doctrine. Certainly, he was not evangelical Protestant in the typical sense of the term. He was, for instance, a sacramental and liturgical Christian. He believed in purgatory and prayers for the dead. He believed in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, though he refused to take sides in disputes over the precise nature of the Presence. He affirmed a form of doctrinal development and even sometimes behaved as if he thought there was something of a Magisterium, or teaching Church, within Christendom, although he never associated it in any particular way with the Papacy. He regularly went to Confession, a practical allowed for in the "high church" wing of Anglicanism, but not widely encouraged in the Church of England. Furthermore, many distinctively Protestant tenets–such as the twin pillars of Reformation Christianity, sola scriptura and justification by faith alone–receive little or no emphasis in Lewis.

To be sure, strands of Lewis’s Ulster Protestantism occasionally found their way into his writing, and it is clear that he didn’t regard Catholicism as adding anything necessary to "mere Christianity." Lewis was no papist (though rumors circulated in Oxford that he was secretly a Jesuit!). Distinctively Catholic doctrines were he contended, at best, items that suited certain temperaments. Nevertheless, the evangelical Protestant who accepts Lewis as a reliable guide to "mere Christianity" will have to accept distinctively Protestant doctrines as likewise optional or "extras." That approach is but one step shy of denying Protestantism, for it implies that what was at stake in the Reformation was not the Gospel itself, as the Reformers thought. The next step is to ask, "What is the Church?", a question Lewis seemingly never fully confronted, but which many of his non-Catholic readers do. And when they do, they often come up with the Catholic answer.

In recent years Lewis has come under attack, even from within the Christian household. Some of the criticism may be justified; much of it certainly isn’t. The charge is leveled that Lewis’s work often falls outside the exacting lines of professional theology. To that Lewis himself would, no doubt, plead guilty. He didn’t claim to be a professional theologian, only, as we have seen, a translator of their work to the people at large.

Other critics point to Lewis’s personal life and allege hypocrisy, even that he had an immoral sexual liaison with an older woman. Lacking substantial evidence, those who thus charge him are reduced to rumor-mongering and gossip. Still others criticize his disciples as too eager to quote Lewis blindly and let their master do their thinking for them–an accusation with some validity perhaps, but as applied to the "disciples," not to Lewis, who never sought disciples for himself. The disciples he made were for Christ.

The fact remains, to his critics’ displeasure, that Lewis, born at the end of the nineteenth century, continues to be immensely relevant at the beginning of the twenty-first century. That is, if intelligent, imaginative, traditional, and ecumenically sound Christianity remains relevant–which we can be certain it does, based on an Authority vastly superior to that of C.S. Lewis.

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles:

• An Hour and a Lifetime with C.S. Lewis | An IgnatiusInsight.com Interview with Dr. Thomas Howard

• C.S. Lewis’s Case for Christianity | An Interview with Richard Purtill | By Gord Wilson

• Paganism and the Conversion of C.S. Lewis | Clotilde Morhan

C. S. Lewis | Ignatius Press resources:

• Remembering C.S. Lewis: Recollections of Those Who Knew Him

• C.S. Lewis for the Third Millenium | by Peter Kreeft

• C.S. Lewis' Case for the Christian Faith | by Richard Purtill

• The Complete Chronicles of Narnia | by C.S. Lewis (single, hardcover volume)

• The Chronicles of Narnia Set | by C.S. Lewis (7-volume set, softcover in case)

• Chronicles of Narnia Set (3 tapes)

• The Life of C.S. Lewis: Through Joy and Beyond (DVD)

• Shadowlands (BBC edition; DVD)

• The Magic Never Ends (DVD)

• Literary Giants, Literary Catholics | by Joseph Pearce

• Literary Converts | by Joseph Pearce

Mark Brumley is President of Ignatius Press.

Mark Brumley is President of Ignatius Press.

An former staff apologist with Catholic Answers, Mark is the author of How Not To Share Your Faith (Catholic Answers) and contributor to The Five Issues That Matter Most. He is a regular contributor to the InsightScoop web log.

He has written articles for numerous periodicals and has appeared on FOX NEWS, ABC NEWS, EWTN, PBS's NewsHour, and other television and radio programs.

November 21, 2013

Vatican II, Salvation, and the Unsaved: A CWR Symposium

Vatican II, Salvation, and the Unsaved: A CWR Symposium

Introduction by Carl E. Olson, Editor of Catholic World Report

This special CWR symposium, consisting of eight essays, is the result of a promise made earlier this year as well as the desire to address and discuss some timely questions related to the Year of Faith (which concludes this Sunday on the Feast of Christ the King), the 50th anniversary of the Second Vatican Council, and the New Evangelization.

In April, CWR published a review by Dr. David Paul Deavel of Dr. Ralph Martin's book, Will Many Be Saved? What Vatican II Actually Teaches and Its Implications for the New Evangelization (Eerdmans, 2012). It was then decided that the review would be withdrawn until a later time; as Mark Brumley, president of Ignatius Press and publisher of CWR, explained, CWR wished “to provide a fuller treatment of a difficult subject than the original review, in my opinion, is able to provide. … The goal is to try to understand what’s what, who’s who, and how best to proceed in fulfilling the Great Commission, without overlooking the genuine nuances and insights theological wisdom provides.”

To that end, we asked six theologians to take up one, two, or all three of the following questions:

• What did the Council say about the possibility of salvation for those who do not know the Gospel of Christ or his Church?

• What are the reasons for the apparent widespread loss of emphasis on evangelization following the Council?

• How can the directives of Vatican II and recent popes about evangelization be best explained and implemented?

Those theologians are Douglas Bushman, STL, Dr. Nicholas Healy, Father David Meconi, SJ, Tracey Rowland, Father James V. Schall, SJ, and Father Thomas Joseph White, OP.

This symposium includes Dr. Deavel’s original review, as well as essays from the seven authors above. It concludes with the essay, “Did Hans Urs von Balthasar Teach that Everyone Will Certainly be Saved?” by Mark Brumley.

• “Every one to whom much is given, of him will much be required” by Douglas Bushman

• Vatican II and the “Bad News” of the Gospel by David Paul Deavel

• The Universality of Christ’s Saving Mission – The Teaching of Vatican II by Nicholas J. Healy, Jr.

• Salvation and Christian Evangelization: Vatican II in Continuity with Tradition by Father David Vincent Meconi, SJ

• Salvation and Missionary Work after Ad Gentes by Tracey Rowland

• On Universal Salvation: The Logic by James V. Schall, SJ

• Who Will Be Saved? The Council and the Question of Salvation by Father Thomas Joseph White, OP

• Did Hans Urs von Balthasar Teach that Everyone Will Certainly be Saved? by Mark Brumley

An interview with novelist Michael D. O’Brien

The prolific novelist, Michael O'Brien, discusses his new novel, Voyage to Alpha Centauri, with the folks at IPNovels.com:

Michael D. O’Brien is the author of several novels, with his latest work, Voyage to Alpha Centauri, taking his tally to ten. We were able to nab the busy author and artist for an interview to give us a peek into his first-ever sci-fi novel, his writing process, and more. Fans and new readers, grab a warm beverage and get to know the best-selling author of Father Elijah, Eclipse of the Sun, and Island of the World!

You’re well known around the world for your novels, many of which grapple with the weighty issues facing our society today. But now you’re writing science fiction. Is that much of a departure from your other work?

O’Brien: Yes, it’s a radical departure from my other nine novels. For many years I’ve been fascinated by the immensity and beauty of the universe, dabbled in astronomy, and often yearned to go “out there,” as impossible as that is. Over the years I’ve pondered these desires and have come to some conclusions about them. Science fiction offers a kind of psychological stepping outside our normal perceptions and categories of thought. We can look at human nature, I think, I hope, with a shade more objectivity. All true cultural works do this in a sense, but sci-fi offers a means to step very far indeed.

From Fahrenheit 451 to Brave New World to 1984, not to mention C.S. Lewis’s Space Trilogy, science fiction has often been a vehicle to express concerns about the direction our world could be headed, often in quite a prophetic way. What themes do you think crop up in Voyage to Alpha Centauri that pertain to some of the directions our society is heading?

O’Brien: There are several. I have worked into the narrative, as the background of the lives of the voyageurs, the condition of Earth about a hundred years from now. Mankind is ruled by “totalitarianism with a friendly face,” a world government that controls more or less everything; technology is rewarding and omnipresent, surveillance is sophisticated and subtle; all sexual morality has been relativized, depopulation laws are draconian, sterility is highly rewarded, fertility is punished, etc. , etc. Green is good, organized religion is bad. The social matrix appears to be peaceful and “democratic” and yet there is very limited personal freedom.

So, Voyage to Alpha Centauri is a kind of anti-utopia or a dystopia?

O’Brien: It’s not merely a dystopian novel in the social and political sense. It also asks metaphysical questions: For example, what is it in human nature that compels us to look beyond the purely material? The scientists and other staff on the ship are the best and brightest of mankind, and along with their strengths they bring their weaknesses and blindness with them on the voyage. What are they seeking when they yearn to escape gravity, escape our planet and our solar neighborhood? What, really, does man hope to find out there in the stars? Is it no more than our abiding desire for increased knowledge? Or is there in us an inherent suppressed desire for transcendence?

Who are your favorite science fiction authors?

A Pilgrimage in Rome—At Home: An interview with George & Stephen Weigel

A Pilgrimage in Rome—At Home | Carrie Gress | Catholic World Report

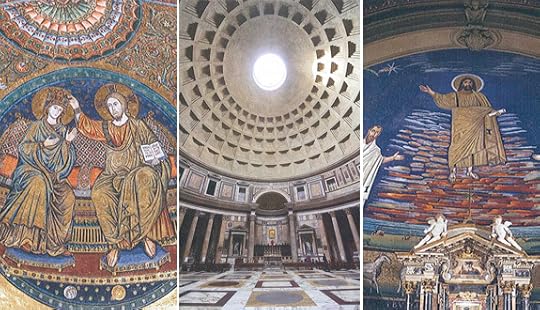

George Weigel and his photographer son, Stephen Weigel, talk about their book, Roman Pilgrimage: The Station Churches

One of the best-kept secrets of lived Catholicism in Rome, the station churches pilgrimage, which dates back to the earliest centuries of Christianity, can now be experienced by the faithful worldwide in George Weigel's latest book, Roman Pilgrimage: The Station Churches (Basic Books, 2013), co-authored with art historian Elizabeth Lev, and featuring the photography of his son, Stephen.

George and and Stephen Weigel spoke recently with Catholic World Report about the new book.

CWR:Roman Pilgrimage is a day-by-day journey to forty historic churches in Rome. What is significant about these holy sites and this "pilgrimage" around the city?

George Weigel: The "station churches" of Rome take the pilgrim back to the very first centuries of Christian life in the city, as virtually all of them are associated with early Christian martyrs. To make the pilgrimage to the prescribed "station church" for each day of Lent is to relive the experience of the pope and the people of Rome in the first millennium, when popes led a daily procession through the city to the "station" of the day, where Mass was celebrated and the day's fast broken by a post-Mass communal meal. In addition to being a marvelous way to deepen one's experience of Lent (and Easter Week, for the pilgrimage extends through the Octave of Easter), the station church pilgrimage is also a splendid way to "learn Rome" and to explore some of its hidden artistic treasures.

CWR: Who do you envision reading this book? Is it just for those who are actually in Rome for Lent?

George Weigel: Roman Pilgrimage is a good way to "do Rome at home"—that is, to make the Lenten station church pilgrimage from your living room or study, a day at a time, reflecting on each day's liturgical texts and getting to know each day's stational church. So the book really is for everyone. Those planning on taking it to Rome as a companion to do at least a part of the pilgrimage might want to order the eBook, which is gorgeous (all photos are in color) and a lot easier to carry around.

CWR: The book is an insider's look at one of the best-kept secrets of those who live in Rome, although it is certainly not new. What do you think makes this book "work" to bring the experience to those who may have never even stepped foot in the Eternal City?

George Weigel: In addition to being a guide book to more than three dozen venerable churches and their unique architectural and artistic histories, Roman Pilgrimage is a spiritual companion to Lent and a means of discovering the baptismal character of the Lenten season, which is for all Christians, not just the Church's enrolled catechumens. In a sense, Lent invites every Catholic to re-enter a kind of catechumenate each year, examining conscience and pondering the ways in which we have and haven't practiced the imitation of Christ during the previous twelve months. The splendid cycle of Lenten biblical and patristic readings at Holy Mass and in the Liturgy of the Hours offers an unparalleled richness of material for reflection, amplified by the experience of beauty as a "rumor of angels" that everyone takes from the experience of the station churches. Thus after making the "Forty Days" through the station church pilgrimage, we can renew the promises of our own baptism with real conviction, and fully appreciate being blessed with baptismal water at the Easter Vigil or on Easter Sunday.

CWR: Art historian Elizabeth Lev also worked on this project with you. What was her unique contribution to the book?

November 20, 2013

New: "Voyage to Alpha Centauri: A Novel" by Michael O'Brien

Now available from Ignatius Press:

Voyage to Alpha Centauri: A Novel

by Michael O'Brien

Set eighty years in the future, this novel by the best-selling author Michael O'Brien is about an expedition sent from the planet Earth to Alpha Centauri, the star closest to our solar system. The Kosmos, a great ship that the central character Neil de Hoyos describes as a "flying city", is immense in size and capable of more than half light-speed. Hoyos is a Nobel Prize winning physicist who has played a major role in designing the ship.

Hoyos has signed on as a passenger because he desires to escape the seemingly benign totalitarian government that controls everything on his home planet. He is a skeptical and quirky misanthropic humanist with old tragedies, loves, and hatreds that are secreted in his memory. The surprises that await him on the voyage-and its destination-will shatter all of his assumptions and point him to a true new horizon.

Science fiction and fantasy literature are genres that have become dominant forces in contemporary worldwide culture. Our fascination with the near-angelic powers of new technology, its benefits and dangers, its potential for obsession and catastrophe, raises vital questions that this work explores about human nature and the cosmos, about man's image of himself and where he is going-and why he seeks to go there.

Michael O'Brien, iconographer, painter, and writer, is the popular author of many best-selling novels including Father Elijah, The Father's Tale, Eclipse of the Sun, Sophia House, Theophilos, and Island of the World. His novels have been translated into twelve languages and widely reviewed in both secular and religious media in North America and Europe. He lives in Ontario with his wife, Sheila, and family.

Praise for Voyage to Alpha Centauri:

"Michael O'Brien is a superior spiritual story teller worthy to join the ranks of C.S. Lewis, Flannery O'Connor, Graham Greene, and Evelyn Waugh."

- Peter Kreeft, Ph.D., Boston College

"Some Sci Fi novels are scientism fiction, worshiping science. Others are science friction, where high tech makes humans lowly. Voyage to Alpha Centauri, though, neither creates a new god nor blames science for our sin. Its narrator excitedly embarks on a 19-year trip aboard a sleek, huge spaceship, only to learn of oppression in the heavens as on earth, with big brothers watching and demanding lying conformity. Michael O'Brien shows us the battle that ensues and its sensational result as he skillfully portrays a clash of world views without end, amen."

- Marvin Olasky, Editor-in-chief, World Magazine

"Ingenious, expansive, and enduringly wise, Voyage to Alpha Centauri is a tour de force of storytelling and moral imagination--sparkling in its humanity, rich in its embroidery, and chilling in its plausibility. It is a parable of an age that could easily become our own, with its concomitant wonders and dangers, an exploration of the most sublime heights and of the greatest depths of human possibility, and a thought-provoking meditation on the ethical limits of knowledge. In Voyage to Alpha Centauri, Michael O'Brien has given us a literary treasure and a deeply satisfying read."

- Corban Addison, Author, A Walk Across the Sun

November 18, 2013

Catholicism and the Convenience of Empty Labels

by Carl E. Olson | Catholic World Report | Editorial

When the language of American politics is used to define Catholic belief and practice, the result is confusion, discord, and ideological obfuscation

“Philadelphia Archbishop Charles J. Chaput, a leading conservative in the Roman Catholic hierarchy, defended himself Tuesday against perceptions that he is hostile to the more liberal inclusiveness of Pope Francis.” — “Chaput to Catholics: Don't use Francis to 'further own agendas'” by David O'Reilly (Philly.com; Nov. 13, 2013)

“Incredulity is the neglect of revealed truth or the willful refusal to assent to it. 'Heresy is the obstinate post-baptismal denial of some truth which must be believed with divine and catholic faith, or it is likewise an obstinate doubt concerning the same; apostasy is the total repudiation of the Christian faith; schism is the refusal of submission to the Roman Pontiff or of communion with the members of the Church subject to him.'” — Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC), 2089 (quoting from Code of Canon Law, 751)

“...” — Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC) on the terms “liberal” and “conservative”

I have a dream. In it, a man dressed in strange clothing stands in front of the courthouse in downtown Eugene, Oregon, just a ten minute drive from my home. He begins to preach. He speaks of Jesus Christ, of God, of the Church, of the need for salvation. At one point he quotes another author, saying, “Anyone who does not pray to the Lord prays to the devil. When we do not profess Jesus Christ, we profess the worldliness of the devil, a demonic worldliness.” He speaks of the Cross. The small crowd gathered before him snicker; there is some hissing.

Then the man calmly states, “ Every unborn child, condemned unjustly to being aborted, has the face of the Lord, who before being born, and then when he was just born, experienced the rejection of the world.” Someone shouts, “You're a fanatic, old man! Go home!” The man smiles, unswayed. He concludes by remarking on the power of baptism: “The Church teaches us to confess our sins with humility, because only in forgiveness, received and given, do our restless hearts find peace and joy.” A woman sneers, “Take your talk of sin somewhere else, you fundamentalist!” Someone else mutters, “Yeah, that's what the world needs—more conservative Christian ideology.”

Yes, it's just a dream. But if you know anything about Eugene, Oregon—or other university towns with the same hip, enlightened, progressive, educated citizenry—you know it's not far from reality.

The strange thing is that when this man gets up in front of crowds of tens of thousands in St. Peter's Square and says the same things, he is described by many as “liberal”. In fact, arguments and debate over whether or not Francis is a “liberal” have been both common and heated in recent months. Many in the American media, however, have already made up their minds: yes, the new pope is “liberal”, and that supposed fact is a big problem for those “conservative” bishops who keep harping about fringe issues such as the killing of the unborn, sexual immorality, the familial foundations of society, and the need to evangelize.

Fabricated Conflicts, Lacking Contexts

The quote above, about Francis and Abp. Chaput, is a good example. Chaput, readers are informed, is “a leading conservative in the Roman Catholic hierarchy” who is, in some form or fashion, in conflict with “the more liberal inclusiveness of Pope Francis.” Is it because Pope Francis is for abortion, “same-sex marriage,” co-habitation, and contraceptives? Is it because Chaput is against higher taxes, is for building more fences on the U.S.-Mexican border, and thinks the term “social justice” should be banished from use in the Catholic Church? Is it because the two have been sending out tweets blasting the other as “extremist”, “right-wing”, and “leftist”?

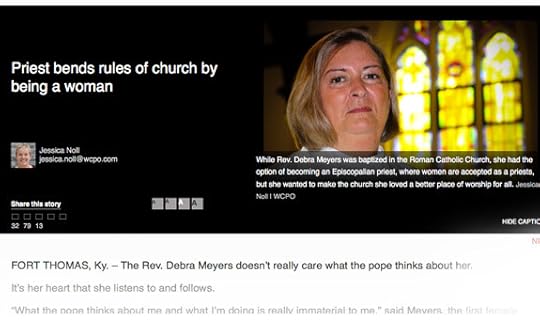

And the winner of the worst pro-women's ordination article of all time is...

by Carl E Olson | CWR Blog

Longtime readers of the Insight Scoop blog (est. A.D. 2004) know that I occasionally break from the modest, cerebral approach that characterizes the vast majority of my writing (yes, that was typed keyboard-in-cheek) in order to rant a bit about certain pet peeves. One that holds a certain pride of place are badly written, incoherent, and theologically clueless pieces—press releases, really—celebrating some brave woman who is now a "Catholic priest", made so by the power vested in her by herself.

There have been some strong contenders over the years. But this WCPO.com (Cincinatti) article is the hands-down winner in my book, which means it is actually a loser of comical proportions. First, the headline:

Priest bends rules of church by being a woman

In a parallel world, where reality and truth prevail, the headline would be:

Woman breaks rules of Catholic Church by pretending to be a priest

In a parallel fashion, in a non-ecclesial setting, it would be:

Man breaks state law by impersonating a police officer

But the author, Jessica Noll, has her riveting headline and plunges bravely into the shallow waters beneath it:

Justice, Mercy, and the Drama of Redemption

by Fr. James V. Schall, SJ | Catholic World Report

A world of automatic salvation would not be worth creating or worthy of God

“God, who is justice and truth, does not judge by appearances.”

— Antiphon #3, Daytime Prayer, Wednesday, Week III, Roman Breviary.

“But you, God of mercy and compassion, / slow to anger, O Lord, / abounding in love and truth, / turn and take pity on me.”

— Psalm 86.

“Clemency, though she is invoked by those who deserve punishment, is respected by innocent people as well. Next, she can exist in the person of the innocent, because sometimes misfortune takes the place of crime; indeed, clemency not only succors the innocent, but often the virtuous, since in the course of time it happens that men are punished for acts that deserve pardon. Besides this, there is a large part of mankind which might return to virtue, if the hope of pardon were not denied them.”

— Seneca, “On Clemency,” I, 2.

I.

The philosopher Plato was worried about whether or not the world was created in justice, since it did not seem to be. For in it, the innocent were often punished but many of the guilty went away untouched. While tyrants died in their beds, heroes languished in prison. Pope Benedict XVI held that the best chance of our seeing the good and necessity of the resurrection was through the logic of the virtue of justice. The actual persons who committed the crimes or who did the virtuous act had to be judged and properly punished or rewarded. Otherwise, no real and ultimate justice could take place. Without the immortality of the soul and the resurrection of the body, the world is created in injustice.

Aquinas too asked whether the world was created in justice. He said that it was created in mercy, not justice. Machiavelli, however, held that if we were merely just, we would be destroyed by the unjust. Thus, it was necessary also to be wicked at times, lest we perish. In C. S. Lewis’ novel, Till We Have Face, the Greek philosopher is asked, “Then the world is not created in justice?” He replies, “Thank God that it is not.” Finally, one of the first and most celebrated remarks of Pope Francis was: “The truth is that I am a sinner whom the mercy of God has loved in a special way.” If there are sinners in the world, they have no hope without there also being mercy, not merely justice.

Christianity professes to be a revelation of God’s love, the full dimensions of which are incomprehensible to us because of the limited nature of our being. We are finite beings who are created good but are not gods. However, Christianity affirms that things can be figured out by human reason since we depend on them and acknowledge them as true. We can know what is true. We know it when we affirm in our minds what is actually there in reality. Through our minds, we have a real connection with what is. The truths about the inner life of God and our relation to it are beyond the power of our reason, though not contradictory to it. We can think on them when we come to know them. In thinking of them, we learn to think better than when we only think of natural and human things.

Christianity purports to be grounded in the truth, the whole truth, not just that part of truth naturally open to human reason. It acknowledges that all truth fits together in a consistent order. It conceives that the purpose of the mind is to know this order. But can a society without justice or mercy be a society of truth?

November 16, 2013

The Day, the End, and a New Beginning

"The Destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem" by Francesco Hayez (1867)

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Sunday, November 17, 2013 | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Mal 3:19-20a

• Ps 98:5-6, 7-8, 9

• 2 Thes 3:7-12

• Lk. 21:5-9

By my highly unscientific estimation, the world has ended several hundred times in my lifetime, courtesy of nuclear war, overpopulation, famine, disease, global cooling, global warming, and so forth. This is not to make light of those serious realities, to the extent that they are realities. But we can be tempted to interpret every sort of current event as a sign of world’s imminent demise. And, unfortunately, this can lead to all sorts of problems, including a misreading of certain passages of the Bible.

Today’s Gospel reading from Luke 21 is one such passage. This passage, along with Mark 13 and Matthew 24, are sometimes called “little apocalypses,” and have been subject to just about every sort of interpretation imaginable. C. S. Lewis was so distressed by the contents of these passages that he wrote, in the essay “The World’s Last Night,” that Jesus’ statement, “Truly, I say to you, this generation will not pass away till all has taken place” (Lk 21:32) is “certainly the most embarrassing verse in the Bible.” Lewis then argued (not very convincingly) that Jesus had indeed been ignorant in saying that world would end within forty years of His utterance.

Lewis’s perplexity is understandable, even if his attempt to solve the difficulty is not. A challenging feature of Luke 21 is that it records Jesus talking about three different events or realities: the persecution of Christians prior to the fall of the Temple in A.D. 70, the time of the fall of the Temple and the city of Jerusalem at the hands of the Roman army, and the time of the Son of Man. Although Jesus distinguished between these three events, He also presented them as being closely related to one another.

Jesus had, throughout His ministry, proclaimed that He was the true Prophet, the fulfillment of previous prophets’ statements and desires, and the savior of Israel. In today’s reading from the prophet Malachi, we are presented with a prophecy about “the day”—the day of liberation from the oppression and bondage endured at the hands of “the proud” and “the evildoers.” Many first-century Jews believed this liberation involved political and military revolution and would result in the overthrow of Roman rule. But Jesus went to great lengths to teach—often with parables—and to show—by signs and miracles—that His kingdom was being established to liberate the people from far worse sources of oppression: sin and death.

In Luke 21, Jesus prophesied that the Temple, one of the most impressive structures of the ancient world, would be torn down, stone by stone. Asked for a sign indicating the timing of this stunning event, Jesus exhorted His listeners to be both vigilant and wary against false preachers. He used the language of the Old Testament prophets to describe the sort of political and social upheaval that the early Christians would hear about and experience. These included persecution, for just as Jesus would be persecuted and killed (Lk 9:44; 18:32), many of his followers would undergo the same, described often by Luke in the Acts of the Apostles (cf., Acts 4:3; 5:18; 8:3; 9:4).

The destruction of the Temple one generation from the death and Resurrection of Christ was a sign that the beginning of a new era in God’s work of salvation had begun. As the Catechism points out, Jesus “even identified himself with the Temple by presenting himself as God's definitive dwelling-place among men. Therefore his being put to bodily death presaged the destruction of the Temple, which would manifest the dawning of a new age in the history of salvation…” (par 586). That age, of course, is the age of the Church, which is the seed of the Kingdom.

The fulfillment of Jesus’ words demonstrated that He is a true prophet and that there is nothing to be embarrassed about. On the contrary, Luke 21—as challenging and complex as it is—proves once again the truthfulness of the promises of the Son of God.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the November 18, 2007, issue of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

November 15, 2013

The Thought and Work of C.S. Lewis

by Carl E. Olson

Friday, November 22nd, marks the 50th anniversary of the deaths of three famous and intriguing men: the author and agnostic Aldous Huxley; the 35th President of the United States, John F. Kennedy; and the author and apologist, C. S. Lewis. (For a fictional discussion among the three, see Peter Kreeft's book, Between Heaven and Hell: A Dialog Somewhere Beyond Death with John F. Kennedy, C. S. Lewis & Aldous Huxley.)

While I think Huxley's Brave New World is a brilliant book that is that proven remarkably prophetic in many ways, and while I wonder where Kennedy would fit in today's political landscape if he were here today (perhaps a moderate Republican?), Lewis has had the biggest impact on my life and thought. The first book by Lewis that I read, while in high school, was Surprised by Joy, and I soon read several others. After all these years, what I find most remarkable about Lewis' writing is the wide breadth and the brisk lucidity. My favorite books by Lewis are Abolition of Man, the collection, On Stories: And Other Essays on Literature, and, yes, Surprised by Joy.

The following is an essay I wrote a number of years ago, meant to be a short introduction to the his work and perhaps of interest to those who are just discovering Lewis.

The Thought and Work of C.S. Lewis

There’s no doubt about the ongoing popularity of C.S. Lewis’s many books and stories. He is one of the best-selling authors of all-time; his Narnian series alone has sold over 100 million copies since it was first published between 1950 and 1956. His works of Christian apologetics—including Mere Christianity, The Great Divorce, and The Screwtape Letters—are read and admired by Christians ranging from Catholics to Baptists to Methodists to Eastern Orthodox. And his lesser-known works of literary criticism, such as The Discarded Image, a study of the medieval view of the world, and English Literature in the Sixteen Century Excluding Drama, are still greatly admired by specialists and students.

Like many prolific and accomplished authors, Lewis possessed formidable skills, discipline, and focus. Those who knew him were often astounded at his prodigious intellect; he could quote entire pages of medieval poetry from memory and most of his books and essays were "first takes" – he rarely revised a first draft. As a young man he was a top student who read widely and deeply, the recipient of a traditional classical education.

The Desire for Joy

However impressive his learning and skills, there is a much more mysterious quality behind the distinctive features of Lewis’s writing and thinking – the reality of Joy. It is for good reason that Lewis’s account of his formative years was titled Surprised By Joy since the elusive experience of "Joy" powerfully shaped his life and thought, as he indicated in many of his writings.

As a young boy of six Lewis experienced the sensation of "enormous bliss" on a summer day, accompanied by the memory of a toy garden in his nursery. "It was a sensation, of course, of desire," he wrote in Surprised By Joy, "but desire for what?" That sudden sensation ceased but "in a certain sense everything else that had ever happened to me was insignificant in comparison." That elusive Joy was the subject of early poetry, of his first work of prose, The Pilgrim’s Regress, and of his famous sermon, The Weight of Glory.

Closely related to his search for Joy was his love for myth and mythology. As a young man, Lewis again experienced Joy when he immersed himself in Norse mythology. Yet he also abandoned Christianity because he became convinced it was just one myth among many and a product of human invention. But a long conversation with J.R.R. Tolkien and Hugo Dyson in September 1931 opened his eyes to the uniqueness of the "true myth" called Christianity. "Now the story of Christ," he wrote, "is simply a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened." It was this true myth–the life, death, and Resurrection of Jesus Christ–that Lewis would devote much of his energy and ability toward explaining and defending for the next thirty years of his life.

Remorseless Clarity

Retired professor of English literature Dr. Thomas Howard has studied C.S. Lewis’s work for over fifty years (he corresponded with Lewis in the 1950s and met him briefly in England) and has written numerous articles and a book about the famous author. Asked about the continued popularity of Lewis’s books, Dr. Howard states: "Lewis’s popularity derived, I am sure, from the remorseless clarity of everything he wrote, plus his glorious imagination, plus his splendid mastery of the English language. Of course his gigantic intellect and his rigorous training in argument . . . set his work altogether apart from most other writers, especially popular writers …" Lewis’s ability to powerfully convey the deeper truths of the Christian Faith with clarity, liveliness, and conciseness is undoubtedly a significant part of his wide appeal.

In addition, as a former atheist, Lewis understood the thinking and objections of unbelievers and met them on their ground, using their standards of empirical proof and rational thinking in combating their challenges to Christianity. Although not a theologian, he was trained in philosophy and was well acquainted with the many philosophical schools and ideological fads of his time. Two such "isms"–subjectivism and scientism–were often addressed in his works of fiction (Out of the Silent Planet, for example) and non-fiction (Miracles and The Abolition of Man). Since Lewis defended "mere Christianity" against those "isms" antagonistic to traditional Christian doctrines and mostly avoided intra-Christian controversies, it is not altogether surprising that he is widely read by Catholics, Protestants, and Eastern Orthodox.

Imagination and Analogy

Lewis’s fiction has sometimes been criticized for being too obviously Christian (a complaint made by J.R.R. Tolkien). But Lewis always insisted that his stories came not from the desire to make a point or press an argument, but from pictures and images in his mind that he wove together into a story. Yet it is also clear that many of his works of fiction contain implicit denials of secularism and endorsements of theism.

This ability to connect concrete images to abstract thoughts is a notable strength of Lewis’s popular apologetics. There are many example of this use of analogy in Mere Christianity, considered by many to be one of the finest works of popular apologetics ever written. He employs the analogy of reading music in distinguishing between instincts ("merely the keys" of an instrument) and the universal Moral Law ("tells us the tune to play"). And in arguing for the transcendence of God he writes that "if there was a controlling power outside the universe, it could not show itself to us as one of the facts inside of the universe–no more than the architect of a house could actually be a wall or staircase or fireplace in that house."

As Chad Walsh observes in The Literary Legacy of C.S. Lewis (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1979), this use of analogy "transforms an abstract philosophic proposition into a mental picture." He adds that these analogies "are little poems interspersed in the prose text," bringing to life ideas that might otherwise sound dry and dull.

Anemic Ecclesiology

Even those Catholics who express great admiration for Lewis point out that one of the weaknesses of Lewis’s theological and apologetic writings is a weak, or hazy, view of the Church. In an otherwise glowing analysis of C.S. Lewis recently published in First Things magazine ("Mere Apologetics", June/July 2005), Avery Cardinal Dulles, author of A History of Apologetics , wrote: "As Lewis’ greatest weakness, I would single out his lack of appreciation for the Church and the sacraments. … His ‘mere Christianity’ is a set of beliefs and a moral code, but scarcely a society. In joining the [Anglican] Church he made a genuine and honest profession of faith–but he did not experience it as entry into a true community of faith. He found it possible to write extensively about Christianity while saying almost nothing about the People of God, the structure of authority, and the sacraments."

Howard is even more blunt, saying that Lewis "avoided, like the black pestilence, the whole topic of The Church":

He hated ecclesiology. It divided Christians, he said (certainly accurately). He wanted to be known as a "mere Christian," so he simply fled all talk of The Church as such. He would not participate in anything that remotely resembled a discussion of matters ecclesiological. He was firm in his non- (or anti-?) Catholicism.

But would Lewis have remained an Anglican if he were alive today? "People ask me if he would by now have been received into the Ancient Church," Howard stated, "and I usually say yes. I don’t see how, as an orthodox Christian apologist, he could have stayed in the Anglican Church during these last decades of its hasty self-destruction." Joseph Pearce wrote in C.S. Lewis and the Catholic Church (Ignatius Press, 2003):

We can’t know for certain what Lewis would have done had he lived to see the triumph of modernism in the Church of England and the defeat of "mere Christianity". There is no doubt, however, that he would have felt strangely out of place in today’s Anglican church. There is also no doubt that today’s Anglican church sees him as a somewhat embarrassing part of their unenlightened and reactionary past. The sobering truth is that even if Lewis had not chosen to leave the Church of England, the Church of England would have chosen to leave him. (p. 167)

The irony, Pearce notes, is that although Lewis is today ignored by most Anglicans, he is embraced by two groups with whom he had, at best, an uneasy relationship: conservative Evangelicals and orthodox Catholics.

Conclusion

Lewis modestly insisted that his work was not original, nor did he care to be original. Yet however orthodox his beliefs and traditional his views, Lewis’s superb style, articulation, and creativity stand out – as does his ability to touch the human heart. He honestly speaks to spiritual longing that all of us experience, but often cannot articulate. Lewis encountered and pursued Joy and through his writings millions of others have been led to embrace the true myth of the Incarnate Word.

(A shorter version of this article appeared in the December 4, 2005 issue of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers