Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 112

January 28, 2014

Saint Thomas Aquinas, Priest and Doctor of the Church

Saint Thomas Aquinas, Priest and Doctor of the Church | Various Authors | January 28, 2014 | The Feast of Saint Thomas Aquinas

From Saint Thomas Aquinas: "The Dumb Ox" by G.K. Chesterton

by G.K. Chesterton

Thomas was a huge heavy bull of a man, fat and slow and quiet; very mild and magnanimous but not very sociable; shy, even apart from the humility of holiness; and abstracted, even apart from his occasional and carefully concealed experiences of trance or ecstasy.

St. Francis was so fiery and even fidgety that the ecclesiastics, before whom he appeared quite suddenly, thought he was a madman. St. Thomas was so stolid that the scholars, in the schools which he attended regularly, thought he was a dunce. Indeed, he was the sort of schoolboy, not unknown, who would much rather be thought a dunce than have his own dreams invaded, by more active or animated dunces. This external contrast extends to almost every point in the two personalities.

It was the paradox of St. Francis that while he was passionately fond of poems, he was rather distrustful of books. It was the outstanding fact about St. Thomas that he loved books and lived on books; that he lived the very life of the clerk or scholar in The Canterbury Tales, who would rather have a hundred books of Aristotle and his philosophy than any wealth the world could give him. When asked for what he thanked God most, he answered simply, "I have understood every page I ever read." St. Francis was very vivid in his poems and rather vague in his documents; St. Thomas devoted his whole life to documenting whole systems of Pagan and Christian literature; and occasionally wrote a hymn like a man taking a holiday.

They saw the same problem from different angles, of simplicity and subtlety; St. Francis thought it would be enough to pour out his heart to the Mohammedans, to persuade them not to worship Mahound. St. Thomas bothered his head with every hair-splitting distinction and deduction, about the Absolute or the Accident, merely to prevent them from misunderstanding Aristotle. St. Francis was the son of a shopkeeper, or middle class trader; and while his whole life was a revolt against the mercantile life of his father, he retained none the less, something of the quickness and social adaptability which makes the market hum like a hive. In the common phrase, fond as he was of green fields, he did not let the grass grow under his feet. He was what American millionaires and gangsters call a live wire. It is typical of the mechanistic moderns that, even when they try to imagine a live thing, they can only think of a mechanical metaphor from a dead thing. There is such a thing as a live worm; but there is no such thing as a live wire. St. Francis would have heartily agreed that he was a worm; but he was a very live worm. Greatest of all foes to the go-getting ideal, he had certainly abandoned getting, but he was still going.

St. Thomas, on the other hand, came out of a world where he might have enjoyed leisure, and he remained one of those men whose labour has something of the placidity of leisure. He was a hard worker, but nobody could possibly mistake him for a hustler. He had something indefinable about him, which marks those who work when they need not work. For he was by birth a gentleman of a great house, and such repose can remain as a habit, when it is no longer a motive. But in him it was expressed only in its most amiable elements; for instance, there was possibly something of it in his effortless courtesy and patience.

Every saint is a man before he is a saint; and a saint may be made of every sort or kind of man; and most of us will choose between these different types according to our different tastes. But I will confess that, while the romantic glory of St. Francis has lost nothing of its glamour for me, I have in later years grown to feel almost as much affection, or in some aspects even more, for this man who unconsciously inhabited a large heart and a large head, like one inheriting a large house, and exercised there an equally generous if rather more absent-minded hospitality. There are moments when St. Francis, the most unworldly man who ever walked the world, is almost too efficient for me.

From Guide to Thomas Aquinas  by Josef Pieper

by Josef Pieper

In the midst of the tremendous demands made upon him by his teaching, and challenged by questions shot at him from every side--in the midst of all this intellectual commotion, Thomas wrote his great systematic works. Some of them are the more or less direct fruit of his teaching itself. But his greatest systematic works, the Summa theologica and the Summa Against the Pagans, were not. His works--the sheer physical labor they represent is in itself imposing—can probably be explained in only one way: that Thomas was present in the body amid the fret and fever of those times, especially of the Parisian disputes, but that all the while he dwelt in an inner cloister of his own, that his heart was wholly untouched and untroubled, concentrated upon the totality of reality; that wrapped in the silence that filled the innermost cell of his soul he simply did not hear the din of polemics in the foreground; that he listened to something beyond it, something entirely different, which was the vital thing for him.

Perhaps we may say that several elements contributed to his imperturbability: a mystic (in the narrower sense) rapture; the capacity to give himself entirely to a subject (once, dictating at night. he simply did not notice that the candle in his hand had burned down and was singeing his fingers); and finally a concentration, acquired by schooling of the will, which made it possible for him to dictate to three or four scribes simultaneously—different text, of course. In this way and under such conditions he produced, in a lifetime of not quite fifty years, that vast body of work which in printed editions fills thirty folio volumes.

From The Unity of Philosophical Experience  by Etienne Gilson

by Etienne Gilson

While so many men were trying to base philosophy on theological foundations, a very simple and modest man as putting everything in its place. His name was Thomas Aquinas, and he was saying things so obviously true that, from his time down to our own day, very few people have been sufficiently self-forgetful to accept them. There is an ethical problem at the root of our philosophical difficulties; for men are most anxious to find truth, but very reluctant to accept it. We do not like to be cornered by rational evidence, and even when truth is there, in its impersonal and commanding objectivity, our greatest difficulty still remains; it is for me to bow to it in spite of the fact that it is not exclusively mine, for you to accept it though it cannot be exclusively yours. In short, finding out truth is not so hard; what is hard is not to run away from truth once we have found it. When it is not a "yes but", our "yes" is often enough a "yes, and..."; it applies much less to what we have just been told than to what are about to say. The greatest among philosophers are those who do not flinch in the presence of truth, but welcome it with the simple words: yes, Amen.

St. Thomas Aquinas was one of the latter, clear-sighted enough to know truth when he saw it, humble enough to bow to it in its presence. His holiness and his philosophy sprang from the same source: a more than human eagerness to give way to truth; but he was surrounded by men who did not like to do that, at least not to the same degree, so that, even after him, everything went on as if truth had remained unsaid. Yet his ideas were clear and simple. Himself a theologian, St. Thomas had asked the professors of theology never to prove an article of faith by rational demonstration, for faith is not based on reason, but on the word of God, and if you try to prove it, you destroy it. He had likewise asked the professors of philosophy never to prove a philosophical truth by resorting to the words of God, for philosophy is not based on Revelation, but on reason, and if you try to base it on authority, you destroy it. In other words, theology is the science of those things we are received by faith from divine revelation, and philosophy is the knowledge of those things which flow from the principles of natural reason. Since their common source is God, the creator of both reason and revelation, these two sciences are bound ultimately to agree; but if you really want them to agree, you must first be careful not to forget their essential difference. Only distinct things can be united; if you attempt to blend them, you inevitably lose them in what is not union, but confusion.

From Sermon in a Sentence: St. Thomas Aquinas  selected and arranged by John P. McClernon

selected and arranged by John P. McClernon

St. Thomas may be best known as a great intellect and Christian thinker, but his holy life was equally impressive. Although graced with such an incredibly mastery of knowledge, in his personal life he exemplified a simple, reserved, humble servant of God. He was known to rise early in the morning, with the usual practice of going to confession, saying Mass, then immediately attending another Mass. The rest of his day he normally spent reading, praying, writing, and teaching. Thomas liked to go often to a church and spent quiet time there with Jesus in the tabernacle. His heart was drawn like a magnet to prayer whenever confronted with a theological or intellectual question that challenged him. God once revealed to St. Catherine of Siena, the great fourteenth-century Dominican Doctor and mystic, that "Thomas learned more from prayer than from study." Since he had a profound devotion to Mass and the Holy Eucharist, and it was not uncommon for his Dominican brethren to find him so deeply moved and absorbed during the service that he would stop, needing to be roused to continue. The sacredness of the Mass and his corresponding love of God simply overwhelmed him.

All those who knew Thomas found him to be considerate, kind, and patient with other people. He exhibited no trace of vanity or pride, so often found in those of great intellectual ability or personal achievements. Friendship, according to Thomas, is the greatest model for understanding and learning charity. He was never known to lose his temper, even in the midst of heated disputations, and never uttered anything unkind or humiliating to those opposing his views.

From Defenders of the Faith in Word and Deed  by Fr. Charles P. Connor

by Fr. Charles P. Connor

Saint Thomas surely knew controversy in his life, but he did not write the Summa Theologica as a work of refutation. Rather, he wished to tell the entire story of God and the universe he created as the Church understands it through Scripture, tradition, and the use of reason. Aquinas was not the most widely read philosopher of his day (John Duns Scotus supposedly had a larger following), but no one captured God, the Divine Intelligence, in quite the same way. In an amazingly logical and sequential pattern, Thomas traces man's creation and fall from grace and the tremendous events enabling creatures to return to God, namely, the Incarnation of Christ, his subsequent Redemption of the world, the Church he established, the sacraments he gave to his Church, and the grace he continually bestows on men as the most vital means to achieve their eternal salvation.

"St. Thomas of Aquin," by Robert Farren, from Saints For Now  edited by Clare Boothe Luce

edited by Clare Boothe Luce

You cannot put such a life into a dozen pages; you can simply suggest what it was and send readers further to adequate accounts. But much less than tell Aquinas' life in these pages can I say what his was and how significant it is. One can hint at it by saying that he is the prince of theologians, the great master of Christian philosophers, the reconciler or the Greek with the Hebrew and the Latin genius; and one can say that the popes praise him in a tireless succession of words. One can say that the hand of Thomas is discernible in every orthodox theologian, and that when Pius XII spoke about the age of the world to the Pontifical Academy of the Sciences, the bone of his discourse was an argument which Thomas perfected. One can say that the revival of his thought in the past fifty years, after centuries of neglect and contempt among most intellectuals, is one of the chief facts of our time. One can say that the dignity of the Catholic intelligence, its superb comprehensiveness and penetrating clarity, are manifested and sustained in him unassailably and fructifyingly. And after ejaculating in this fashion, unsatisfactorily, one can first thank God abundantly for Thomas and then go and read him, the Perennial Philosopher.

Other Books & Resources Relating to St. Thomas Aquinas:

• Summa Theologica (softcover) | St. Thomas Aquinas

• Summa of the Summa | Peter Kreeft

• Shorter Summa | Peter Kreeft

• Guide to Thomas Aquinas | Josef Pieper

• The Human Wisdom of St. Thomas | Josef Pieper

• John Paul II & St. Thomas Aquinas | John Paul II

• St. Thomas Aquinas Commentary on Colossians | St. Thomas Aquinas

• Thomas Aquinas and the Liturgy | David Berger

• Trinity in Aquinas | Gilles Emery

• The Quiet Light: A Novel about St. Thomas Aquinas | Louis de Wohl

• St. Thomas Aquinas and the Preaching Beggars | Brendan Larnen, Milton Lomask, and Leonard Everett Fisher

St. Thomas Aquinas and the Thirteenth Century

St. Thomas Aquinas and the Thirteenth Century | Josef Pieper | From the opening chapter of Guide to Thomas Aquinas | January 28, 2011 | Ignatius Insight

So bound up is the life of St. Thomas Aquinas with the thirteenth century that the year in which the century reached its mid-point, 1250, was likewise the mid-point of Thomas' life, though he was only twenty-five years old at the time and still sitting at the feet of Albertus Magnus as a student in the Monastery of the Holy Cross in Cologne. The thirteenth century has been called the  specifically "Occidental" century. The significance of this epithet has not always been completely clarified, but in a certain sense I too accept the term. I would even assert that the special quality of "Occidentality" was ultimately forged in that very century, and by Thomas Aquinas himself. It depends, however, on what we understand by "OccidentaIity." We shall have more to say on this matter.

specifically "Occidental" century. The significance of this epithet has not always been completely clarified, but in a certain sense I too accept the term. I would even assert that the special quality of "Occidentality" was ultimately forged in that very century, and by Thomas Aquinas himself. It depends, however, on what we understand by "OccidentaIity." We shall have more to say on this matter.

There exists the romantic notion that the thirteenth century was an era of harmonious balance, of stable order, and of the free flowering of Christianity. Especially in the realm of thought, this was not so. The Louvain historian Fernand van Steenberghen speaks of the thirteenth century as a time of "crisis of Christian intelligence"; [1] and Gilson comments: "Anybody could see that a crisis was brewing." [2]

What, in concrete terms, was the situation? First of all we must point out that Christianity, already besieged by Islam for centuries, threatened by the mounted hordes of Asiatics (1241 is the year of the battle with the Mongols at Liegnitz)—that this Christianity of the thirteenth century had been drastically reminded of how small a body it was within a vast non-Christian world. It was learning its own limits in the most forceful way, and those limits were not only territorial. Around 1253 or 1254 the court of the Great Khan in Karakorum, in the heart of Asia, was the scene of a disputation of two French mendicant friars with Mohammedans and Buddhists. Whether we can conclude that these friars represented a "universal mission sent forth out of disillusionment with the old Christianity," [3] is more than questionable. But be this as it may, Christianity saw itself subjected to a grave challenge, and not only from the areas beyond its territorial limits.

For a long time the Arab world, which had thrust itself into old Europe, had been impressing Christians not only with its military and political might but also with its philosophy and science. Through translations from the Arabic into Latin, Arab philosophy and Arab science had become firmly established in the heart of Christendom—at the University of Paris, for example. Looking into the matter more closely, of course, we are struck by the fact that Arab philosophy and science were not Islamic by origin and character. Rather, classical ratio, epitomized by Aristotle, had by such strangely involved routes come to penetrate the intellectual world of Christian Europe. But in the beginning, at any rate, it was felt as something alien, new, dangerous, "pagan."

During this same period, thirteenth-century Christendom was being shaken politically from top to bottom. Internal upheavals of every sort were brewing. Christendom was entering upon the age "in which it would cease to be a theocratic unity," [4] and would, in fact, never be so again. In 1214 a national king (as such) for the first time won a victory over the Emperor (as such) at the Battle of Bouvines. During this same period the first religious wars within Christendom flared up, to be waged with inconceivable cruelty on both sides. Such was the effect of these conflicts that all of southern France and northern Italy seemed for decades to be lost once and for all to the corpus of Christendom. Old monasticism, which was invoked as a spiritual counterforce, seems (as an institution, that is to say, seen as a whole) to have become impotent, in spite of all heroic efforts to reform it (Cluny, Cîteaux, etc.). And as far as the bishops were concerned—and here, too, of course, we are making a sweeping statement—an eminent Dominican prior of Louvain, who incidentally may have been a fellow pupil of St. Thomas under Albertus Magnus in Cologne, wrote the following significant homily: In 1248 it happened at Paris that a cleric was to preach before a synod of bishops; and while he was considering what he should say, the devil appeared to him. "Tell them this alone," the devil said. "The princes of infernal darkness offer the princes of the Church their greetings. We thank them heartily for leading their charges to us and commend the fact that due to their negligence almost the entire world is succumbing to darkness." [5]

But of course it could not be that Christianity should passively succumb to these developments. Thirteenth-century Christianity rose In Its own defense, and in a most energetic fashion. Not only were great cathedrals built in that century; It saw also the founding of the first universities. The universities undertook, among other things, the task of assimilating classical ideas and philosophy, and to a large extent accomplished this task.

There was also the whole matter of the "mendicant orders," which represented one of the most creative responses of Christianity. These new associations quite unexpectedly allied !hemselves with the institution of the university. The most important university teachers of the century, in Paris as well as in Oxford, were all monks of the mendicant orders. All in all, nothing seemed to be "finished"; everything had entered a state of flux. AIbertus Magnus voiced this bold sense of futurity in the words: Scientiae demonstrativae non omnes factae sunt, sed plures restant adhuc inveniendae; most of what exists in the realm of knowledge remains still to be discovered. [6]

The mendicant orders took the lead in moving out into the world beyond the frontiers of Christianity. Shortly after the nuddle of the century, while Thomas was writing his Summa Against the Pagans, addressed to the mahumetistae et pagani, [7] the Dominicans were founding the first Christian schools for teaching the Arabic language. I have already spoken of the disputation between the mendicant friars and the sages of Eastern faiths in Karakorum. Toward the end of the century a Franciscan translated the New Testament and the Psalms into Mongolian and presented this translation to the Great Khan. He was the same Neapolitan, John of Monte Corvino, who built a church alongside the Impenal Palace in Peking and who became the first Archbishop of Peking.

This mere listing of a few events, facts, and elements should make it clear that the era was anything but a harmonious one. There is little reason for wishing for a return to those times—aside from the fact that such wishes are in themselves foolish.

Nevertheless, it may be said that in terms of the history of thought this thirteenth century, for all its polyphonic character, did attain something like harmony and "classical fullness." At least this was so for a period of three or four decades. Gilson speaks of a kind of "serenity." [8] And although that moment in time is of course gone and cannot ever again be summoned back, it appears to have left its traces upon the memory of Western Christianity, so that it is recalled as something paradigmatic and exemplary, a kind of ideal spirit of an age which men long to see realized once more, although under changed conditions and therefore, of course, in some altogether new cast.

Now as it happens, the work of Thomas Aquinas falls into that brief historical moment. Perhaps it may be said that his work embodies that moment. Such, at any rate, is the sense in which St. Thomas' achievement has been understood in the Christian world for almost seven hundred years; such are the terms in which it has repeatedly been evaluated. Not by all, to be sure (Luther called Thomas "the greatest chatterbox" among the scholastic theologians [9]); but the voices of approbation and reverence have always predominated. And even aside from his written work, his personal destiny and the events of his life unite virtually all the elements of that highly contradictory century in a kind of "existential" synthesis. We shall now speak of these matters at greater length, and in detail.

First of all, a few remarks regarding books.

The best introduction to the spirit of St. Thomas is, to my mind, the small book by G. K. Chesterton, St. Thomas Aquinas. [10] This is not a scholarly work in the proper sense of the word; it might be called journalistic—for which reason I am somewhat chary about recommending it. Maisie Ward, co-owner of the British-American publishing firm which publishes the book, writes in her biography of Chesterton [11] that at the time her house published it, she was seized by a slight anxiety. However, she goes on to say, Étienne Gilson read it and commented: "Chesterton makes one despair. I have been studying St. Thomas all my life and I could never have written such a book." Still troubled by the ambiguity of this comment, Maisie Ward asked Gilson once more for his verdict on the Chesterton book. This time he expressed himself in unmistakable terms: "I consider it as being, without possible comparison, the best book ever written on St. Thomas. . . . Everybody will no doubt admit that it is a 'clever' book, but the few readers who have spent twenty or thirty years in studying St. Thomas Aquinas, and who, perhaps, have themselves published two or three volumes on the subject, cannot fail to perceive that the so-called 'wit' of Chesterton has put their scholarship to shame. . . . He has said all that which they were more or less clumsily attempting to express in academic formulas." Thus Gilson. I think this praise somewhat exaggerated; but at any rate I need feel no great embarrassment about recommending an "unscholarly" book.

ENDNOTES:

[1] Fernand van Steenberghen, Le XIIIe siècle. In Forest, van Steenberghen, and de Gandillac, Le Mouvement doctrinal du Xle au XIVe siècle. Fliche-Martin, Histoire de l'Eglise vol. 13 (Paris, 1951), p. 303.

[2] Etienne Gilson, History of Christian Philosophy in the Middle Ages (London and New York, 1955), p. 325.

[3] Friedrich Reer, Europäische Geistesgeschichte (Stuttgart, 1953), p.147.

[4] Marie-Dominique Chenu, Introduction à l'etude de St. Thomas d'Aquin (Paris—Montreal, 1950), p. 13.

[5] Gustav Schnürer, Kirche und Kultur im Mittelalter (Paderborn, 1926), II, p. 441.

[6] Liber primus Posteriorum Analyticorum, tract. 1, cap. 1 Opera Omnia. Ed. A. Borgnet (Paris, 1890), tom. 2, p. 3.

[7] C. G. 1,2.

[8] Gilson, History, p. 325.

[9] Joseph Lortz, Die Reformation in Deutschland (Freiburg im Breisgau, 1939), I, p. 352.

[10] Heidelberg, 1956.

[11] Maisie Ward, Gilbert Keith Chesterton (New York, 1943), p. 620.

Editor's note: Pieper's book was originally published in English in 1962 by Pantheon Books. The Ignatius Press edition was published in 1991.

Related Ignatius Insight Links/Articles:

• Saint Thomas Aquinas, Priest and Doctor of the Church | Various Authors

• The Roots of Culture | by Fr. James V. Schall, S.J. | The Foreword to Josef Pieper's Leisure: The Basis of Culture

• Philosophy and the Sense For Mystery | An excerpt from For The Love of Wisdom: Essays On the Nature of Philosophy

Other Books & Resources Relating to St. Thomas Aquinas:

• Summa Theologica | St. Thomas Aquinas

• Sermon in a Sentence, Vol. 5: Thomas Aquinas | Selected/arranged by John P. McClernon

• Guide to Thomas Aquinas | Josef Pieper

• The Human Wisdom of St. Thomas | Josef Pieper

Saint Thomas Aquinas: "The Dumb Ox" | G. K. Chesterton

• Summa of the Summa | Peter Kreeft

• Shorter Summa | Peter Kreeft

• John Paul II & St. Thomas Aquinas | John Paul II

• St. Thomas Aquinas Commentary on Colossians | St. Thomas Aquinas

• Thomas Aquinas and the Liturgy | David Berger

• Trinity in Aquinas | Gilles Emery

• The Quiet Light: A Novel about St. Thomas Aquinas | Louis de Wohl

• St. Thomas Aquinas and the Preaching Beggars | Brendan Larnen, Milton Lomask, and Leonard Everett Fisher

Josef Pieper (1904-1997) is widely considered to be one of the finest Catholic philosophers of the 20th century. He was educated in the Greek classics and the writings of St. Thomas Aquinas. He was a professor of philosophy at the University of Münster in Germany. His books have earned international acclaim from both Catholic and non-Catholic scholars. Read much more about his life and work on his IgnatiusInsight.com Author Page.

January 26, 2014

Satan, Sin, and Sociology

Satan falling from heaven, as depicted by Gustave Dore in an illustration for

John MIlton's "Paradise Lost".

Satan, Sin, and Sociology | Anne Hendershott | CWR blog

A clear-eyed understanding of sin has been replaced by a therapeutic culture and "psychological man”

In his first homily, given on March 14th, Pope Francis cautioned the faithful that “he who does not pray to the Lord, prays to the devil.” “When we do not profess Jesus Christ,” he further insisted, “we profess the worldliness of the devil, a demonic worldliness.” Since that day, he has spoken often of the one he has called the “prince of this world,” and the “father of lies.” And, in the book, On Heaven and Earth, then-Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio devoted an entire chapter to “The Devil”, warning that Satan’s fruits are “destruction, division, hatred and calumny.”

For many Catholics—especially post-Vatican II Catholics—speaking aloud of evil, sin, and Satan is something they may never have experienced, even in Church. Some may have to resort to the internet (or dictionary) to look up a definition of calumny. It seems that after a long hiatus, evil and sin have been “rediscovered” by some.

More than sixty years ago, T. S. Eliot wrote about the sense of alienation that occurs when social regulators begin to splinter and the controlling moral authority of a society is no longer effective. He suggested that a “sense of sin” was beginning to disappear. In his play, The Cocktail Party, a troubled young protagonist visits a psychiatrist and confides that she feels “sinful” because of her relationship with a married man. She is distressed not so much by the illicit relationship, but rather, by the strange sense of sin. Eliot writes, “Having a sense of sin seems abnormal” to her—she had never noticed before that such behavior might be seen in those terms. She believed that she had become “ill.”

Writing in 1950, Eliot knew that the language of sin was declining even then, yet most of us would assume that the concept of sin was still strong. Looking back though, it seems that for many, the sense of sin was already beginning to be replaced by an emerging therapeutic culture. Within that growing culture of “liberation”, people no longer viewed themselves as sinful when they drank too much, took drugs, or engaged in violent or abusive behaviors. Rather, such actions were increasingly viewed as indicators that such individuals were victims of an illness they had little or no control over.

Promoted by the psychological community and popularized by practitioners like Carl Rogers, the therapeutic mentality began seeping into the Church as psychologists began advising Catholic dioceses about implementing the therapeutic culture within the Church itself.

New: "Saint Peter" DVD (starring Omar Sharif)

Now available from Ignatius Press:

DVD | 197 minutes

Saint Peter tells the epic story about the key event in European and World history, the spread of Christianity throughout the Roman Empire, focusing on the leader of that new religion. St. Peter is played by the renowned

Egyptian actor, Omar Sharif (Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago).The film illustrates the strong reaction of Romans and Jews from a political and religious standpoint, and it also deals with the immense obstacles Christianity found along its path in the early stages of its development.

As a dedicated follower of Christ, Peter spreads the message of the Gospel across the land, often staying only one step ahead of those determined to persecute him. As the tension between the Christians and the Romans grows, blood runs in the streets. Peter and Paul meet and together they form a strong friendship in preaching about Christ.

While fleeing persecution in the Eternal City, Peter sees Jesus walking toward him saying, "Peter, I am coming to Rome, to be crucified again." Peter realizes he must follow Christ to the end, and returns to Rome to be crucified like his master.

Also stars Lina Sastri, Daniele Pecci, Flavio Insinna, Claudia Koll and Sydne Rome. Directed by Giulio Base.

Special Features: 16-page Companion Collector's Booklet (by Carl E. Olson); "Behind the Scenes" Film; Film Trailer; Scene Selections

This DVD contains the following language options: English with English or Spanish subtitles.

Stills from the film:

January 25, 2014

Jesus is not a mere fact, but a living invitation

"The Calling of the Apostles Peter and Andrew" by Duccio (1311)

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Sunday, January 26, 2014 | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Is 8:23-9:3

• Ps 27:1, 4, 13-14

• 1 Cor 1:10-13, 17

• Mt 4:12-23

In the opening paragraphs of his encyclical on hope, Pope Benedict XVI observed that the Christian message of the Gospel is not just “informative”—that is, filled with good content—just also “performative.” This means that “the Gospel is not merely a communication of things that can be known—it is one that makes things happen and is life-changing. The dark door of time, of the future, has been thrown open” (Spe Salvi, par 2).

Sacred Scripture can be read in different ways. One way of reading it is to sift through its contents in order to gain information about, say, moral teachings, cultural artifacts, and historical facts. We can—and should—read the Gospels in order to learn about Jesus Christ. But many people read about Jesus and never believe He is the Son of God who came to save the world. On the contrary, many people who know the Bible quite well do not believe the information contained within it is true or even helpful. As Benedict wryly noted in his book, Jesus of Nazareth, there are some biblical scholars who spend much time and effort undermining and even attacking the content of Scripture.

The opening verses of Matthew 4, which come immediately prior to today’s Gospel reading, describe Jesus being tempted by Satan in the desert. The evil one demonstrates how adept he is at quoting Scripture in an attempt to destroy Jesus. “The devil,” quipped Benedict, “proves to be a Bible expert who can quote the Psalm exactly” (Jesus of Nazareth, 35). Likewise, Jesus was often persecuted most intently by scribes whose lives were devoted to reading and interpreting the Law of Moses.

Today’s Gospel recounts that Jesus, following the temptation in the desert, withdrew to region of Galilee. He likely did this, on one hand, out of practical necessity, avoiding the possibility of being arrested and killed as John the Baptist had been. But Matthew explains that Jesus, in spending time in the region of Zebulun and Naphtali, also brought light—that is, the good news about the Kingdom of heaven—to an area described in terms of “darkness” and “death.” Many centuries prior, around 900 B.C., these two regions, which were to the west and north of the Sea of Galilee, had been conquered by Syria. Nearly two hundred years later they were invaded and annexed by the Assyrians, and most the Jews residing there were taken into exile and replaced with pagan settlers.

It is estimated that in the time of Jesus about half of the population in Galilee was Gentile, hence the name “District of the Gentiles” used by Isaiah in today’s Old Testament reading. Into this land of darkness and death—most likely a reference to the pagan beliefs and practices common to those regions—came the light of Christ. The public ministry of Jesus began with the proclamation, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.” It is the same message John the Baptist preached in the wilderness of Judea (Matt 3:1); the essential difference is the messenger. Whereas John proclaimed the Kingdom and the way of salvation, Jesus is the King and the way of salvation. John’s preaching was informative, but it could not ultimately perform what it pointed toward: the forgiveness of sins and the salvation of souls.

John’s Gospel indicates many of Jesus’ disciples had first been followers of John the Baptist (Jn 1:35-37). These men were probably somewhat familiar with Jesus prior to being called to be “fishers of men.” When the proper time came and they were called away from their boats and livelihood, they immediately followed. The message of Jesus was not, for them, merely information, but a way of living and being. The person of Jesus was not a mere fact, but a living invitation to come into saving communion with the King and His kingdom. Today, the Lord calls us as well—from darkness to light, from death to life, from being fishermen to becoming fishers of men.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the January 27, 2008, issue of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

"Gutting Gutting": Fr. Fessio responds to pro-abort column by Catholic professor

by Carl E. Olson | CWR blog

This week marks the 41st anniversary of "Roe v Wade," and so one of the contibutors to the New York Times wrote a piece titled, "Should Pope Francis Rethink Abortion?" Would you be aghast and amazed if you learned that the author believes that, yes, the pope should change his mind—and the teaching of the Church—about abortion? No?

Would it surprise you at all to know that the author of the piece in question is a Catholic and a professor of philosophy at the University of Notre Dame? Hmmm.

The author, Dr. Gary Gutting, is indeed a professor at Notre Dame, and he explained in a piece last March in the Times that the two sources that define his life are the Enlightenment and the Catholic Church:

These are the sources nurturing the values that define an individual’s life. For me, there are two such sources. One is the Enlightenment, where I’m particularly inspired by Voltaire, Hume and the founders of the American republic. The other is the Catholic Church, in which I was baptized as an infant, raised by Catholic parents, and educated for 8 years of elementary school by Ursuline nuns and for 12 more years by Jesuits. For me to deny either of these sources would be to deny something central to my moral being.

Since Gutting won't deny the Catholic Church as a source nurturing the values that define his life, he apparently deems it necessary to change her. And there's the rub, as he ruefully admits in his new column calling for the Church to abandon her beliefs about conception, life, and the murder of the unborn:

Pope Francis has raised expectations of a turn away from the dogmatic intransigence that has long cast a pall over the religious life of many Roman Catholics. His question “Who am I to judge?” suggested a new attitude toward homosexuality, and he is apparently willing to consider allowing the use of contraceptives to prevent sexually transmitted diseases. But his position on what has come to be the hierarchy’s signature issue — abortion — seems unyielding. “Reason alone is sufficient to recognize the inviolable value of each single human life,” he declared in his recent apostolic exhortation, “Evangelii Gaudium,” adding: “Precisely because this involves the internal consistency of our message about the value of the human person, the church cannot be expected to change her position on this question.”

So, what to do? Gutting's approach is to appeal to reason:

I want to explore the possibility, however, that the pope might be open to significant revision of the absolute ban on abortion by asking what happens if we take seriously his claim that “reason alone is sufficient” to adjudicate this issue. What actually follows regarding abortion once we accept the “inviolable value of each single human life”? This appeal to rational reflection has been a central feature of the tradition of Catholic moral teaching. I put forward the following reflections in the spirit of this tradition.

What follows is, in a word, tortured. Read it for yourself.

Since Gutting is a Catholic professor who was trained for many years by Jesuits, I thought it would be interesting to see what Fr.  Joseph Fessio, SJ, might think of Gutting's arguments. Not one to mince words, Fr. Fessio sent the following remarks about Gutting's column:

Joseph Fessio, SJ, might think of Gutting's arguments. Not one to mince words, Fr. Fessio sent the following remarks about Gutting's column:

He is a very confused philosopher, which makes Notre Dame an especially appropriate place for him.

Major error # 1: his claim and premise that the fetus is only “potentially human”.

a. This raises the question he doesn’t (because he can’t) answer consistently: When does the potentially human being become an actual human being?

b. His arguments against aborting “potentially human” would apply to human sperm and ova which are clearly (only) potentially human.

c. A valid conclusion cannot be drawn from a false premise.

Ergo: His conclusion has not been demonstrated.

Major red herring # 1: comparing a woman who has been raped to the—risibly hypothetical—case of someone who has been kidnapped, whose kidneys have been connected to another person who will die if the connection isn’t maintained for 9 months.

a. We are not obliged to prevent all fatal diseases at the cost of our own life

b. Pregnancy is not a disease

c. The kidnapped person is not the only possible solution to the other person’s kidney problem; perhaps the author has never heard of dialysis.

d. The kidnapped person’s relation to the other person is entirely extrinsic and accidental (in the philosophical sense)

Ergo: non sequitur.

Major red herring # 2: Catholics show they don’t regard the embryo to be as morally relevant as a small child because they don’t support major research into spontaneous abortion of embryos.

a. Who says Catholics would not support such research?

b. We are obliged absolutely not to kill an innocent human being; we are not obliged absolutely to prevent all deaths of innocent human beings.

Ergo: non sequitur.

One final point: Gutting concludes his piece by stating, "There are morally difficult issues about abortion that should be decided by conscience, not legislation. The result would be a church acting according to the pope’s own stated standard: preaching not 'certain doctrinal or moral points based on specific ideological options' but rather the gospel of love." Setting aside Gutting's crude misuse of Francis' words in Evangelii Gaudium (see par. 39), we should note that conscience, as any good Catholic should know, is informed by truth, which is appropriate through both reason and divine revelation:

Faced with a moral choice, conscience can make either a right judgment in accordance with reason and the divine law or, on the contrary, an erroneous judgment that departs from them.Man is sometimes confronted by situations that make moral judgments less assured and decision difficult. But he must always seriously seek what is right and good and discern the will of God expressed in divine law. (CCC, 1786-87)

And: "From its conception, the child has the right to life. Direct abortion, that is, abortion willed as an end or as a means, is a 'criminal' practice (GS 27 § 3), gravely contrary to the moral law." (CCC, 2322).

January 23, 2014

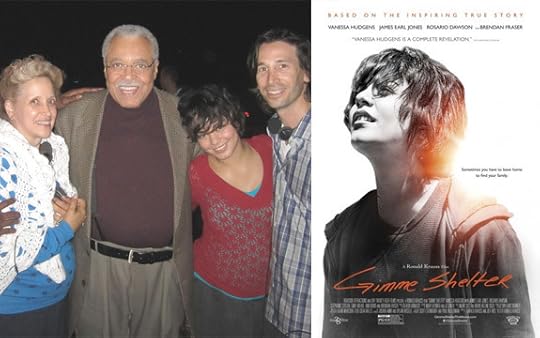

"Gimme Shelter" is about the new face of homelessness—and hope

Kathy DiFiore, on whom the movie "Gimme Shelter" is based, poses with stars of the movie James Earl Jones, Vanessa Hudgens and director-writer Ronald Krauss. (CNS photo/Roadside Attractions)

by Carl E. Olson | CWR blog

Filmmaker Ronald Krauss sees connection with Pope Francis' warnings about “a throwaway culture”

The movie, Gimme Shelter (www.gimmeshelterthemovie.com) which opens in theaters tomorrow, January 24th, features a rising young star, the talents of a gifted director/writer, and a story based on inspiring true events. The star is actress (and singer) Vanessa Hudgens (High School Musical series), the director/writer is Ronald Krauss (Amexica, Puppies for Sale), and the story is rooted in the work and experience of Kathy DiFiore, founder of Several Sources Shelters. The film depicts the struggles and eventual redemption of Agnes “Apple” Bailey (Hudgens), a homeless and pregnant teen. Having run away from her abusive mother (Rosario Dawson) and spurned by her white collar father (Brendan Fraser), she eventually meets a caring stranger (James Earl Jones), who introduces her to a shelter for homeless teenagers.

The movie has been praised by several prominent pro-life leaders, including Cardinal Timothy Dolan, who described Gimme Shelter as a “moving film with an uplifting message of hope and the dignity of human life—and the fact that it is based on real people and events makes it all the more compelling. I hope that this film finds a wide audience—particularly among teens and young adults!”

I spoke by phone recently with both Kathy DiFiore and Ronald Krauss, and the passion of both for helping troubled youths and building a culture of life was obvious. Gimme Shelter, Krauss said, “was 33 years in the making”, a reference to DiFiore establishing her first shelter in 1981. He had heard about Kathy's work through various contacts, and then he learned that her first shelter was less than two miles from his brother's house in New Jersey. “I was immediately intrigued,” Krauss says. “I arranged to visit one of her shelters and I was awed by what I saw.” He visited and met Kathy, discovering a devoted woman who was humble and free of any interest in the spotlight.

Krauss was immediately moved by what he witnessed at the shelter. “I was especially inspired by a couple of the girls” as he learned about their pasts and their struggles. “This movie,” he explains, “is about the new face of homelessness: young women, mostly teens, who are often single mothers.”

He talked with Kathy about a possible documentary. True to form, she didn't want it to be about her, but she did have an idea: making a film focusing on the girls and the shelters. Krauss began working on a script, spending time in shelters getting to know the people there and hearing their stories. He eventually spent a year visiting shelters, recording nearly 200 hours of interview with various young women.

“I'm just one link in the chain”, Krauss insists about the making of Gimme Shelter. The word he kept coming back to is “selflessly”: helping those who have no other means of support and assistance. In order to insure the film's authenticity, Krauss had several of the girls help in the writing process, scheduling “script nights” where they would read some of the script while sharing their thoughts about the story line. “They helped me find the reality of their lives,” Krauss says about the process. “They shared their deepest emotions about what it is to be homeless, to not know where you’re going to be tomorrow.”

Krauss never thought he could cast an established Hollywood actress in the lead role, and planned to cast an unknown. But after meeting with Hudgens, he changed his mind. He noted her hunger for a different role; she wanted to challenge herself as an actress and a person. And after Hudgens accepted the role, Krauss was taken back by her intense preparation. “She spent three weeks living in a shelter, she gained weight for the role, and she chopped off her hair. She really did become 'Apple', her character!” So much so, says Krauss, that he would call her “Apple,” not “Vanessa”, even off the set—“that's how much she became the character.” And that is what Hudgens was hoping to accomplish, having stated that it an “an opportunity to completely transform myself. When I looked in the mirror, I didn’t see myself. The story, which is based on the lives a several young women who stayed at the shelter, is completely terrifying, which was all the more reason why I wanted to do it.”

DiFiore began sheltering several young pregnant women in her home, free of charge, in 1984. Soon thereafter, the state of New Jersey fined her $10,000 for running an illegal boarding home. Her story and her work gained attention in the media, and eventually Sen. Gerald Cardinale sponsored a bill exempting non-profit groups from the legislation. When it appeared that the bill would be vetoed, DiFiore had the idea of contacting Mother Teresa to see if she could help. But she thought the idea was unrealistic—until the next day she “heard a loud voice telling me: call Mother Teresa!” She knew a man who worked in Mother Teresa's soup kitchen, so she called him. His wife answered and told Kathy that her husband had just spoken with Mother Teresa the night before. After a few calls, she got in touch with Mother Teresa, who worked to help her get rid of the fine and to persuade lawmakers to pass the bill.

DiFiore has written a soon-to-be-published book, Gimme Love, Gimme Hope, Gimme Shelter, featuring stories about women like Apple, as well her stories about Mother Teresa and others.

As DiFiore continues her tireless work, Krauss hopes Gimme Shelter will open eyes and hearts. “This is a crucial movie for a crucial time,” he says, “It provides a window into our society. These homeless women are not outcasts; they could be anyone.” The movie, he reflects, will means different things to different viewers, depending on where they are coming from and what their own experiences are. “This is not just a movie; it is a movement to change the culture.”

Krauss sees a strong connection between the film and Pope Francis' warnings about “a throwaway culture” and a “consumerist” mentality that is focused on things rather than on people. He hopes that Francis can see the film as it echoes his messages about the poor, needy. “The Prayer of St. Francis is in the movie,” he says, “and that was shot before Francis was elected.”

Trailer for Gimme Shelter:

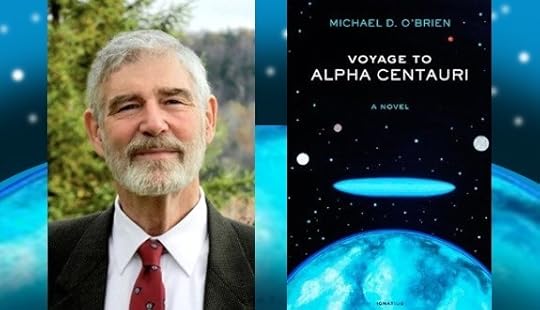

Michael O’Brien’s Literary Icons

Michael O’Brien’s Literary Icons | Eric Thomason | CWR

Voyage to Alpha Centauri explores familiar and timely themes, but in a very different setting.

Michael O’Brien is a superior storyteller and an increasingly bright light in the Catholic literary firmament. The Canadian native's fiction is reminiscent of Tolkien’s: epic in scope, universal in theme, and filled with ordinary characters facing extraordinary obstacles. An iconographer by trade, O'Brien's novels are literary icons, attracting readers with vibrant imagery in order to invite them into a deeper contemplation of eternal truths. O’Brien’s latest work, Voyage to Alpha Centauri, fits this mold.

Alpha Centauri takes place approximately 100 years in the future, at which time a unified world government is preparing to send several hundred elite scientists, scholars, and government officials to explore a potentially habitable planet in the next solar system. The central character is lapsed Catholic Neil de Hoyos, an aging Nobel laureate whose theoretical work made the journey of exploration possible and whose journal entries make up nearly the entirety of the book. The journey to the planet takes nine years, during which time de Hoyos makes unsettling discoveries about governmental intrusion into the private lives of the voyagers. De Hoyos’ journal entries in this phase of the book explore the nature of government, the basis for authentic human community, and the hubris of utopian efforts to perfect man without reference to the transcendent good of the human person. Recounting a mid-journey subversive speech he delivered on governmental social engineering, de Hoyos writes:

We can harness the atom, but we cannot attempt to absolutely control men’s wills, nor their capacity for rational thought, nor their hunger for freedom, without grave risk to man himself. To condition him, to determine him according to arbitrary theories of his nature—his perpetually elusive and mysterious nature—is to deform him. (p. 135)

The government officials on board are swift to respond to such rhetoric. As in several of O’Brien’s other novels, these officials are the immediate face of evil in Alpha Centauri. They are omnipresent, politically correct, unfailingly polite, and utterly ruthless; one colorful character, a hard-drinking Scottish astronomer, delightfully refers to them as “protocol zombies” (p. 50). Presiding over these bland but powerful bureaucrats and leading the response to de Hoyos’ speech is a particularly loathsome character, Dr. Elif Larsson. In a dramatic but private debate with de Hoyos, he offers his defense of increasing governmental control:

How to Oppose the Culture of Death’s Mad Men

Opposing the Mad Men of the Culture of Death | Edward Short | CWR Blog

Our elites consistently exemplify how terribly misguided moral intelligence becomes when ignorant of or defiant of the laws of God

Flying back from London to New York recently, I was reduced to reading the Sunday magazine of the Financial Times, after I found that I had packed away the books I had bought for the flight in my luggage. I share this with my gentle readers because the experience opened my eyes to how aggressively the magazine promotes the culture of death. In a piece on Marin Alsop, for example, the conductor of the Baltimore Symphony was asked what she thought of assisted suicide and she replied, “I believe in giving people the capacity to make ultimate decisions for themselves.” This seemed an odd question to pose in a celebrity interview, even a high-brow celebrity interview. And yet when I went online to verify the conductor’s response, I discovered that the Sunday magazine asks this question of all its celebrities, routinely, week after week. And every one of them replies in the affirmative. Jeffrey Archer, Felicity Kendal, Jamie Morrison, Joanne Harris, Amanda Wakeley and scores of others all sing the same macabre tune: they not only believe in assisted suicide, they champion it, they celebrate it. Ben Fogle speaks for all of them when he says, with a kind of sublime fatuity, “The ultimate human freedom is making your own choices.”

The magazine then asks its interviewees if they believe in an afterlife, and none of them responds in the affirmative. A few wish to imagine their own lives ‘spiritual’ in some unspecified, consoling, self-congratulatory way; but none of them is willing to go so far as to say that there is life after death. Indeed, Alsop gives the most eloquent response to the question of whether she believes in the afterlife when she replies, “Not really.” Here is the wisdom of the age hammered home week after week in one of the establishment’s most highly respected papers.

How should pro-lifers respond to such incessant agitprop? First, we must recognize that, when it comes to questions of elemental ethics, which go to the heart of contraception, abortion, and euthanasia, our elites exemplify how terribly misguided moral intelligence becomes when ignorant of or defiant of the laws of God. To oppose the culture of death, to oppose the sophisticated opinion-makers who have made contraception, abortion and euthanasia pillars of the new world order, we need a countervailing intelligence, one animated by God’s humanizing love, or we shall find ourselves in the same prison of “ultimate human freedom” of which Ben Fogle is so fond.

And to develop this intelligence, we must stop putting our belief in God to one side and imagining that we can reaffirm and defend the sacredness of life by simply invoking human rights or natural law. We must stop being silent on the direct bearing that our dogmatic belief in God has on our understanding of the inviolability of life. And we must stop worrying whether affirming that belief publicly will offend those who believe that killing children in the womb is somehow a requirement of advanced civilization.

Evelyn Waugh, who never passed up an opportunity to mock the progressive new world order, is a good case in point.

January 21, 2014

Carl's Cuts: The First Edition of 2014

by Carl E. Olson | CWR blog

On Jesuit hunters, scandals, Hans Küng, Francis and abortion, "conservatives", Islam, the poor, gossip, the problem with news, and more

• This edition of “Carl's Cuts” was almost ready to post last Friday, and then we lost access to the CWR site for the weekend, and so it languished until now. Or perhaps it aged like fine wine. Or a not-so-fine whine. Here goes!

• The first cut is about cuts, by the great Chesterton: “Catholicism is used to proposals to cut down the creed to a few clauses; but different people have wanted quite different clauses left and quite different clauses cut out. … After nearly two thousand years of this sort of thing, Catholics have come to regard Catholicism as one thing, all the parts of which are in one sense equally assailed and in another sense equally unassailable.” — G. K. Chesterton (The Catholic Church and Conversion)

• I just saw this article about Fr. Mitch Pacwa, SJ, my former professor and spiritual director. Did you know that Fr. Pacwa, best known to many folks for his work at EWTN, was once a community organizer? Or that he is an avid hunter? I really do hope that Fr. Pacwa and my father, who is a gun maker, are able to meet someday. I can see the headline already: “Jesuit Preacher and Protestant Gun Maker Share Favorite Hunting Stories.” I'll buy the beer.

• There are a number of oft-repeated myths about sex abuse by priests in the Catholic Church. One of them is that Pope Benedict did nothing to address it. There are many responses to that, but one of them is this news from BBC: “Close to 400 priests were defrocked in only two years by the former Pope Benedict XVI over claims of child abuse, the Vatican has confirmed.” The piece further notes, referring to an AP report, that “the Vatican also sent another 400 cases to either be tried by a Church tribunal or to be dealt with administratively...” And that's not all that Benedict did. Another myth about the abuse scandals was addressed quite well, in a short space, by Denver Post columnist Electa Draper in this 2010 post:

A steady stream of revelations and civil lawsuits over child sexual abuse by priests seem to signal the Catholic Church has the biggest problem with clerical scandals, but experts deny it is a hot zone of exploitation.

Insurance companies, child advocacy groups and religion scholars say there is no evidence that Catholic clergy are more likely to be involved in sexual misconduct than other clergy or professionals. Yet ongoing civil litigation of decades-old cases against a church with deep pockets keeps the Catholic Church in the headlines.

Back in 2007, the Associated Press published a detailed series on sex abuse and related misconduct and perversions taking place in public schools. It noted: “One report mandated by Congress estimated that as many as 4.5 million students, out of roughly 50 million in American schools, are subject to sexual misconduct by an employee of a school sometime between kindergarten and 12th grade.” Read more here.

• A friend who follows the news in Europe very closely sent me a note after Pope Francis named sixteen new cardinals:

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers