M. Isidora Forrest's Blog, page 39

June 21, 2015

Isis, MacGregor & Moina, Part I

Isis devotees are fortunate in having a long line, though not an unbroken one, of spiritual ancestors that stretches from ancient Egypt to the present. It’s important for us to know our history. Today’s post is the story of two of those ancestors who have definitely made their place in Isiac tradition…

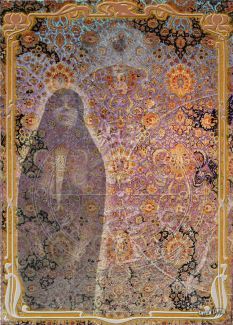

The Golden Dawn by Gwyllm Llwydd; you can get you own copy of this beautiful artwork here.

Established in 1888, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn is one of the most important esoteric groups of the modern age. Its influence on today’s theurgic groups has been immense. The Order is rightly credited with, and sometimes criticized for, bringing together many strands of esoteric wisdom from a variety of traditions and weaving from them a coherent and effective system of spiritual development.

Many modern spiritual groups continue to work the rituals and exercises originally created by the magicians of the Golden Dawn, sometimes unaware of their provenance. Doreen Valiente, a leader in the modern revival of witchcraft, cited the Golden Dawn material as the best way for witches to learn and understand magical technique.

Yet the Order has received scant recognition for the important part it played in the “return of the Goddess” that continues unabated in much of the developed world today.

In the Golden Dawn’s understanding of the Divine, the Feminine Divine is essential and equal. More than a hundred years ago, the GD honored the Goddess by insisting that women and men be admitted “on a perfect equality”. In a paper on the history of the Order, William Wynn Westcott, a co-founder, explained women’s inclusion in the Order in part due to the importance of women in the Ancient Mysteries, “notably those of Isis”.

Florence Farr, GD member and the model for G.B. Shaw’s “New Woman”

It is easy to see why suffragettes and New Women, part of the first wave of modern feminism, were among the Order’s members.

There was, however, a particular Goddess Who particularly inspired two of the Order’s most important members. As you no doubt suspect by now, that Goddess is Isis. The members are MacGregor and Moina Mathers, founding members of the Order.

The Mathers’ Isiac devotions were outside of the Order proper—though Isis is definitely to be found within the Order, too. (For instance, the Order’s Mother Temple was named Isis-Urania and Isis, as well as other Feminine Divine Beings, is found throughout the Order’s curriculum.)

For this post, however, we’ll focus on the Mathers’ personal Work with Isis; and it was personal for they were true devotees and worshippers of the Goddess. What’s more, the Mathers were Isiac evangelists. By the turn of the 20th century, they were living in Paris and publicly performing Isis rites for the avowed purpose of “resurrecting” the worship of Isis and attempting to share the “beautiful truths” they discovered during their study of the religion of Isis, which for Egyptologists was long dead, but was for them “full of life and vital forces.” They believed that the revival of the Isis religion would be a great force for good in the world.

Moina Mathers, circa 1895; if that date is correct, she would have been about 30. Best photo ever!

At first, however, their worship of Isis was private. As so many of us do, they had a private temple in their residence. In an interview about the public rites, MacGregor and Moina said that they began their “Isis Movement” when Jules Bois, a journalist familiar with the Parisian occult scene, asked them to perform a public Isis ceremony at the Bodinière Theatre, a small Paris theatre that could be hired for lectures and performances. At first, they refused, but then Moina had a dream in which Isis gave Her permission for the public ceremony, so they proceeded.

Most of what we know about the Mathers’ Isis Movement are from a few newspaper and periodical articles. An interview with the Mathers and an account of one of their Rites of Isis is given in Frederick Lees’ “Isis Worship in Paris: Conversations with the Hierophant Ramses and the High Priestess Anari” in the February, 1900 issue of The Humanitarian. (The Humanitarian was a progressive periodical published in New York and London and edited by Victoria Woodhull-Martin, a Spiritualist, a Suffragist, and the first woman nominated as a candidate for President of the United States.)

Moina’s famous portrait of her husband in his GD regalia; MacGregor met Moina in the British Museum as she was sketching Egyptian antiquities. Egypt had long been a passion for both.

Yes, you are correct. Ramses and Anari were the Isiac magical names of MacGregor and Moina. Lees describes the Rites of Isis like this:

“In the center of the stage was the figure of Isis, on each side of her were other figures of gods and goddesses, and in front was the little altar, upon which was the ever-burning green stone lamp. The Hierophant Ramses, holding in one hand the sistrum, which every now and then he shook, and in the other a spray of lotus, said the prayers before this altar, after which the High Priestess Anari invoked the goddess in penetrating and passionate tones. Then followed the ‘dance of the four elements’ by a young Parisian lady dressed in long white robes. She had recently become a convert and had previously recited some verses in French in honour of Isis. The four dances were: the ‘dance of the flowers,’ which symbolized the hommage of the earth to the Egyptian goddess; the ‘dance of the mirror,’ that represented waves of water; the ‘dance of the hair,’ symbolic of fire; and the ‘dance of perfumes’ for the element of air. Most of the ladies present in the fashionable Parisian audience brought offerings of flowers, whilst the gentlemen threw wheat upon the altar. The ceremony was artistic in the extreme.”

A magical ceremony as imagined in an illustration of about this period; some have thought that it was supposed to be MacGregor and Moina in their Isis Rites, but I don’t think so. I’ve also seen it called “Necromancy” and I’m thinking that might be more like it given the ghostly look of the floating being between the Pillars.

A reviewer from another newspaper pretty much snarked at the whole thing, especially MacGregor’s “terrible English accent,” but was, however, somewhat smitten with Moina:

“His wife, on the other hand, completely won their sympathy by her graceful attitude and dignified manner. More than that, she is very handsome, she has a beautiful oval face with large black, mysterious eyes—and beauty always tells in Paris.”

The Lees article also included what the black-eyed priestess had to say about priestesses:

The High Priestess Anari holds some very interesting opinions on woman’s role in religion.

“The idea of the Priestess is at the root of all ancient beliefs,” she said, on one occasion. “Only in our ephemeral time has it been neglected. Even in the Old Testament we find the Priestess Deborah, and the New Testament tells us of the Prophetess Anne. What do we find in the modern development of religion to replace the feminine idea, and consequently the Priestess? When a religion symbolizes the universe by a Divine Being, is it not illogical to omit woman, who is the principal half of it, since she is the principal creator of the other half—that is, man? How can we hope that the world will become purer and less material when one excludes from the Divine, which is the highest ideal, that part of its nature which represents at one and the same time the faculty of receiving and that of giving—that is to say, love itself in its highest form—love the symbol of universal sympathy? That is where the magical power of woman is found. She finds her power in her alliance with the sympathetic energies of Nature. And what is Nature if it is not an assemblage of thoughts clothed with matter and ideas which seek to materialize themselves? What is this eternal attraction between ideas and matter? It is the secret of life. Have you ever realized that there does not exist a single flame without a special intelligence which animates it, or a single grain of sand to which an idea is not attached, the idea that formed it? It is these intelligent ideas which are the elementals, or spirits of Nature. Woman is the magician born of Nature by reason of her great natural sensibility, and of her instructive sympathy with such subtle energies as these intelligent inhabitants of the air, the earth, the fire and water.”

The Ecclesiastical Review with the Isis article; click to enlarge and read

Although it all seems a bit stereotypical now, it was pretty strong stuff in its day.

Strangely enough, a summary of the Lees article—noting this topic in particular—found its way into the Church of England Pulpit and Ecclesiastical Review, a source of sermon ideas for clergy. Even more strangely, it was presented positively, which just goes to show how the times, they was a changin’.

There is yet more that we can know about the Mathers’ Parisian Isis work. But we’ll save that for next time as this post is quite long enough for today.

Next week, a pretty wild account of one of the ceremonies as well as images of the Mathers as Ramses and Anari.

Filed under: Goddess Isis Tagged: Aspects of Isis, Deities, Egyptian, Egyptian magic, Experiencing Isis, Feminism, Florence Farr, Goddess, Goddess Feminism, Goddess Isis, Golden Dawn, Golden Dawn curriculum, Golden Dawn magic, Isis history, Isis Movement, MacGregor Mathers, Moina Mathers, Paris

June 14, 2015

Harsiese—Horus, Son of Isis

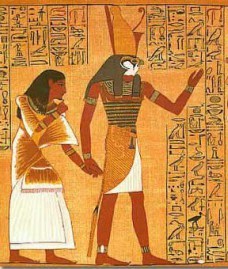

Horus leads Ani before His father Osiris for judgment

This week’s post is inspired by a friend of this blog who was inquiring about how to distinguish the various Horus Gods. (Hint: It ain’t easy.) He was asking about two of Them specifically, as he wished to develop a devotion to Them.

Horus is one of ancient Egypt’s oldest and most important Gods. In fact, many places had their own local form of Horus and there were also other Falcon Gods throughout Egypt Who eventually came to be subsumed in, or at least called by the name of, Horus.

In the earliest texts that have come down to us, there doesn’t seem to have been much of an attempt (or perhaps need?) to separate the Horus Gods. But by the time of the Coffin Texts (beginning around 2100 BCE or so), we have separate funerary formulae for “Becoming Horus the Elder” and for “Becoming Horus.”

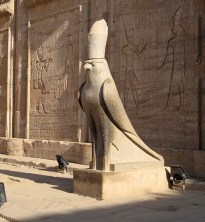

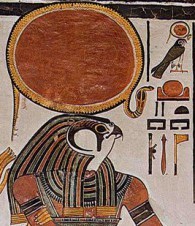

Horus as a falcon at His great temple at Edfu

Scholars don’t know in what part of Egypt Horus’ worship originated. Behdet, a town in the western delta of Lower Egypt, and Nekhen (Hierakonpolis), in Upper Egypt near Luxor, both claimed to be His first cult centers. Interestingly, when His great temple at Edfu in Upper Egypt was built, it was often called by the sacred name of Behdet, though that was not its secular name. The site at Edfu was associated with Horus by the 5th dynasty.

Behdet was so important that Horus is sometimes known as Horus the Behdetite (Hor Behdety). In this aspect, He is usually a protective and powerful warrior—battling the enemies of Re and, of course, the king. Horus the Behdetite may be yet another Horus God that got mixed in with the general Horus blend.

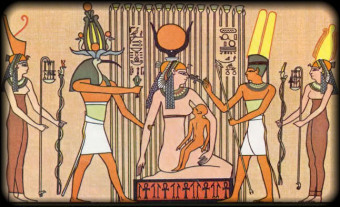

Isis with Her Holy Child

(Another note of interest: the name of the nomarch, that is, the governor of the nome, when Horus is first found at Edfu is Isi; and he served under king Isesi. I wonder if this name connection with Horus’ mother could have led to the king’s and the nomarch’s honoring of Her son at Edfu?)

Whatever the case, let’s focus on this Horus Who is so intimate with Isis. The Greek rendition is Harsiese (HAR-see-AY-say), which is how you will often see it in scholarly works. In Egyptian it is Hor-sa-Iset, “Horus, son of Isis.”

Horus was not originally a part of the same pantheon or ennead (nine Deities) as were Isis and Osiris. The creation story that was told in Heliopolis (near what is now Cairo and called Iunu in Egyptian) consists of Atum—and later, Atum-Re—Who begets Shu and Tefnut, Who beget Nuet and Geb, Who beget Isis and Osiris, Set and Nephthys.

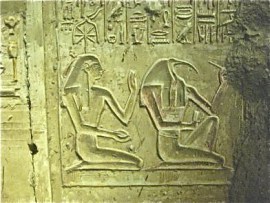

Horus makes the henu gesture of praise

But Horus was too important and too ancient to be left out of the Isis-Osiris myth cycle, which by that time was becoming central to much of Egyptian religion as well as to the kingship. So they found a place for Horus in the Heliopolitan cycle; in fact, they found two places.

Horus, perhaps as Hor Wer, “Horus the Elder” or “Horus the Great,” became the second-born of the Isis-Osiris generation, while Hor-sa-Iset became the Holy Child of Isis and Osiris. I’ve seen this described as a “secondary ennead” at Heliopolis, and the combination may have happened as early as the 4th dynasty (2613-2494 BCE).

The pharaoh continued to be the living embodiment of Horus and to be especially protected by the God, but now he was Horus, Son of Isis, while the deceased pharaoh was Osiris, Beloved of Isis.

Horus in His solar aspect

And while it may have originally been Hor Wer Who battled with Set, now the son of Isis and Osiris opposes Him because of Set’s murder of Horus’ father Osiris and because of Set’s attempt to usurp the throne that rightly belongs to Horus.

It seems that Horus is called Hor-sa-Iset much more often than He is called Hor-sa-Usir (Osiris). Why? It may be because He so strongly takes after His Divine mother.

Like Her, He is a protective and fierce warrior (see more on Fierce Isis here). He fights for His fathers, both Osiris and Re, and He fights for the king. He is a ruler Himself, as is Isis when She rules during Osiris’ civilizing mission throughout the world. As Hor-pa-khred, “Horus the Child,” He is not only protective, but He is also a magical healer—just like His mother Isis.

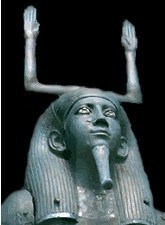

A cippi of Horus

Hor-pa-khred (Harpokrates in Greek) is particularly connected with a protective amulet known as the Cippi or Stele of Horus. These amulets appear to have been most used during the late dynastic period through the Roman. They were intended to protect the home and depicted Horus the Child subduing dangerous creatures such as crocodiles, snakes, lions, and scorpions with His bare hands.

They were also intended to be used for healing from the bites of poisonous creatures. The most famous example is the Metternich Stele, on which we find the tale of Isis and the Seven Scorpions, as well as numerous formulae for the cure of poisoning. This stele also seems to have been one of the magical images over which the sufferer would pour water to absorb the power of the magic words, then drink as a medicine.

One of the formulae on the Metternich Stele has Horus the Child commanding the poison:

Flow out, poison, approach, come forth on earth. It is Horus Who exorcises you, He cuts you to pieces, He spits you out so that you cannot mount up on high but fall to earth. You are weak, you have no strength, you are miserable and cannot fight, you are blind and cannot see, your head is turned upside down and you cannot raise your face. You wander without being able to find your way, you grieve and cannot rejoice, you wander and cannot open your eyes—in accordance with the speech of Horus, Potent of Magic.

A Roman period Harpokrates, urging Mysterious silence

Again, like Isis Herself, Horus the Child is Potent of Magic and a magical healer.

With His connection to His widely worshipped mother, as well as His own magic, Harpokrates became one of the most popular Deities of the common people during the Græco-Roman period.

Images showing the Child God with His finger to His lips (which is merely a representation of the Egyptian hieroglyph for “child”) led Græco-Roman worshippers to interpret Horus as a God of the Mysteries—surely those of His Divine Mother—and urging the initiate to Holy Silence.

Filed under: Goddess Isis, Goddess worship, Modern Paganism Tagged: Ancient Egypt, Aspects of Isis, coffin texts, Deities, Deity, Egypt, Egyptian, Egyptian magic, Goddess, Goddess Isis, Goddess worship, Harpocrates, Harpokrates, Harsiese, Healing of Horus, healing of Isis, Hor Wer, Horus, Horus Son of Isis, Horus the Elder, Isis, Isis Magic, Isis Magic book, Osiris

June 8, 2015

The Great Divine Magicians of Egypt: Isis & Thoth

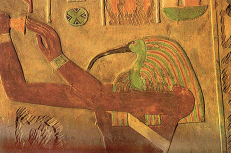

Isis & Thoth (far left and right) add Their magic to Horus’ on the famous Metternich Stele

Ancient Egypt’s two Great Divine Magicians are Isis and Thoth.

Interestingly, both went on to have rather illustrious careers outside Their native Egypt as key players in the Western Esoteric Tradition; Isis as THE quintessential Goddess of esotericism, Thoth as Hermes Trismegistos, THE quintessential teacher of esoteric wisdom.

In fact, the two Divine Magicians have always had a close relationship. Although in earlier Egyptian tradition, Isis is the daughter of Geb and Nuet, Earth God and Sky Goddess, by Plutarch’s time (1st century CE) he is able to say that “many have related that she is the daughter of Hermes,” that is, of Thoth. One inscription calls Her the “vizier and daughter of Thoth.” J. Gwyn Griffiths, one of my favorite scholars, says the two Deities were probably thought to have a family relationship because both were known to be exceptionally wise.

Thoth, Thrice Great

A Hermetic aside

You may be wondering about that Thoth-Hermes connection. How did the Egyptian Thoth and the Greek Hermes become identified? At first glance, it may not seem like They have a lot in common. But not so fast. An important first point of contact is Their connection with souls. Hermes is the psychopomp of the dead, guiding them to the realm of the dead. Thoth, too, is a guide of the dead and takes part in the vital post mortum judgment. Both Gods are associated with the moon and medicine (remember Hermes’s staff the caduceus), and both are known for inventiveness and trickery. The syncretism of Thoth and Hermes eventually resulted in the God/Teacher Hermes Trismegistos, which is an epithet Hermes gets directly from Thoth. In an effort to express Thoth’s majesty, when writing His name Egyptian scribes would often append the epithet Ao, Ao, Ao (literally “Great, Great, Great,” meaning “Greatest”). Greeks and Greek-speaking Egyptians translated the Egyptian epithet as Trismegistos, also using it for ‘their’ Thoth—Hermes. (An excellent book about Hermes Trismegistos’ Egyptian background is Garth Fowden’s The Egyptian Hermes.)

Now back to Isis & Thoth

Thoth & Seshat, the Lady of Books

As noted earlier, the two are linked by Their wisdom. This wisdom, in turn, empowers Their magic. In fact, both work Their magic similarly—primarily by speaking. The words of Isis “come to pass without fail;” the words of Thoth are “Truth.” At Busiris, Isis is even called Djedet Weret, the Great Word, no doubt because of Her magical ability with words. Both are associated with the wisdom and magic of books. Thoth is the patron of scribes and the Divine author of all books. Isis and Thoth together are credited with invention of hieroglyphic and demotic writing in several of the Isis aretalogies. The Cairo calendar calls Isis “provider of the book” and the Oxyrhynchus aretalogy notes Her skill in writing. And, as She is with so many Goddesses, Isis is sometimes assimilated with Seshat, Goddess of Writing.

Both Isis and Thoth are Bird Deities. Thoth is so identified with His sacred bird, the ibis, that He never goes anywhere without His bird head. Some scholars think that his Egyptian name, Djehuty, may come from a very ancient form of the Egyptian word for ibis: djhw. If so, this would speak to the ancient nature of Thoth. Isis, of course, is associated with Her sacred raptor, the kite, and sometimes takes on birdform, through She never appears with just the head of a kite as Thoth does with the ibis.

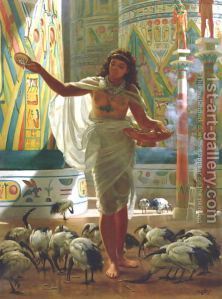

Edward John Poynter: Feeding the Sacred Ibis in the Halls of Karnac

In the ancient world, wisdom could also be expressed in cleverness and even trickery. Both Isis and Thoth can be tricky. In the story of Thoth and Tefnut, Thoth calms the angry Goddess and lures Her back to Egypt by telling Her amusing stories all the while bringing Her closer and closer to home. In the story of the birth of Isis, Osiris, Nephthys, Set, and Horus told by Plutarch, Thoth plays a game with the Moon and wins five extra days in the year during which Nuet can give birth to Her children. The myths of Isis have Her tricking Set time and again to ensure that Horus gets His throne.

One very interesting aspect of the relationship between Isis and Thoth is that Isis often comes to Thoth for help. In the tale of the “Sufferings of Isis,” Isis has been imprisoned by Set in a spinning house. Thoth finds Her and counsels Her (counseling is one of Thoth’s key functions) to escape with Horus to the papyrus swamps, which She does. During the course of the tale, Isis cures the village headwoman’s son of poisoning from seven magical scorpions. (The scorpions were traveling with Isis and got pissed when the headwoman wouldn’t allow the Goddess with Her seven rather scary scorpions in.) Later in the tale, Isis own son, Horus, is poisoned by a scorpion sent by Set and Isis stops the Boat of the Sun to receive magical aid from Thoth.

Isis (in center) of the Bembine Tablet; Thoth, (second from left) has Her back as always

One of the Graeco-Egyptian magical papyri (PGM IV. 94-153) has Isis running to “Ape Thoth, Ape Thoth, my father” in tears because of the adultery of Osiris and Nephthys. It is the beginning of a compulsive erotic spell that (apparently) Thoth is giving to Isis so that She can make Osiris return to Her. Another papyri text (PGM VIII. 1-63) invokes Hermes saying, “Whereas Isis, the greatest of all the gods, invoked you in every crisis, in every district, against gods and men and daimons, creatures of water and earth and held your favor, victory against gods and men and [among] all the creatures beneath the world, so also I, [name of the person invoking], invoke you.”

Thoth aids Isis & Horus in the papyrus swamps

I have often wondered why Isis, Great of Magic, Lady of Words of Power, Greatest of All the Gods, Who Knows Re by His Own Name, would need anyone else’s magical assistance. Perhaps the Thoth-Isis relationship goes back further than we have record of it. If Thoth were the elder Magician, it would make sense to call upon His experience. If Thoth can be considered Her father, calling on Dad for help makes sense, too. Or perhaps we’re seeing an ancient version of something still current among some today. For instance, some say that you shouldn’t do a divination for yourself; you’ll skew the results by being personally involved. Sometimes healers can have trouble healing themselves when they are perfectly wonderful when healing others. Some psychologists, those modern-day shamans, can be perfectly terrible at dealing with their own issues while being a great help to others.

Maybe that’s what’s going on in these tales. Sometimes you need a little distance to see clearly—or magically, in this case. It is always during a personal crisis that Isis calls upon Thoth. When Horus is poisoned, Isis is completely distraught and declares that “my heart is adrift.” In such a state, She is not Her magical self. She needs help. As we all do from time to time. In such times, is is well to have friends to call upon as Isis does in Her great friend Thoth.

Filed under: Goddess Isis Tagged: Divine Magicians, Earth and Sky, Egyptian magic, Goddess Isis, Hermes & Thoth, Hermes Trismegistos, I love Isis, Isis, Isis & Thoth, Isis Magic, J. Gwyn Griffiths, Lady of Books, Sacred Ibis, Thoth

May 31, 2015

Offering to Isis

Nefertari makes offering to Isis

Can Isis smell the flowers we place upon Her altar? Does She eat the delicacies we so carefully arrange upon Her offering mat? Does She drink the wine we pour into a beautiful cup and lift to the smiling lips of our sacred image?

Well, no.

And, yes.

Although I have had weird phenomena happen with offerings—for instance, once an entire two-ounce packet of incense (you DO know how much two ounces of powdered incense is, right?) was apparently incinerated without leaving a whiff of scent in the air of our tiny temple space—usually, the flowers wither naturally, the food dries to inedibility, and the wine evaporates.

So did the Goddess receive Her offerings or not?

An ancient Egyptian offering table

For the ancient Egyptians, the sacred images of the Deities were sacred precisely because they were filled with some measure of the Deity Her- or Himself. Offerings to Isis were received by this bit of the Goddess residing in the image, and through it to Her greater Being.

The main spiritual mechanism for the transfer of an offering from offerent to Deity was the ka, or vital, life energy. All living beings—Deities, human beings, animals, fish, plants, stars, mountains, temples—have a ka. The kas of the Goddesses and Gods are extremely powerful. In one Egyptian creation myth, the Creator Atum embraces His children, the God Shu and the Goddess Tefnut, with His ka in order to protect Them from the primordial chaos of the Nun into which They were born. The ka is a subtle body that exists before a being comes to birth, is joined to that being at birth, lives with her or him throughout life, then travels to the Otherworld after death.

The most haunting of the ka statues; of Awibre Hor

The ka “doubles” the person physically, yet the ka is not essentially personal. It is held in common with all living things—including the Deities. The ka was the ancient Egyptian’s connection to a vast pool of vitality greater than the person her- or himself. During life, the ka is in the body with the ba, the soul. At death, the ka flows back to the spiritual realms. The ba must then follow it in order to be reunited with it. Once the ba and ka are rejoined, the person becomes an akh, a Shining One; that is, a divinized being. Thus the tomb became known as the Place of the Ka and to die was to “go to one’s ka.”

Even though the ancient Egyptian could experience the ka as separate from herself, the ka also connected the person with all that was human for the ka was associated with the ancestors. The ancestors were thought to be the keepers of ka energy. Jeremy Nadler suggests that when people died, the Egyptians believed that they returned to the ka-group of ancestral energy to which each person naturally belonged. In other words, after death, the ka returns to its family.

The ka statue of Amenemhet III

This meant the living had several reasons for making offering to their ancestral dead. As we all do, they wanted to remember loved ones who had died. The offerings provided their ancestor’s kas with the nourishment required to keep the family spirit strong. But since the ancestors had ready access to the greater pool of beneficial ka energy and could bestow it on the living, people could also ask their ancestors to send them a blessing. A blessing of ka energy could nourish human beings, animals, and crops alike.

As usual in Egyptian society, the king was a special case. He could have multiple kas. He also had more intimate contact with the powerful ka energy of his royal ancestors than the average person had with their familial kas. The royal ka was also connected with the power of the God Horus. By the time of the New Kingdom, the king’s ka was specifically identified as Harsiese, “Horus, son of Isis.”

In Egyptian, the word ka is related to numerous words that share its root. Egyptian words for thought, speech, copulation, vagina, testicles, to be pregnant and to impregnate, as well as the Egyptian word for magic (heka), all share the ka root. And all have some bearing on the meaning of ka. Ka is also specifically the word for “bull” and “food.” Connections such as these reveal mysteries. Ka is also the bull because it is a potent, fertile energy that contains the ancestral seeds that connect us with our families. Ka is also food for it is the energy that nourishes life, in both the physical and the spiritual realms. The ka is intimately connected with offering; the plural of ka, kau, was used to mean “food offerings.” Sometimes the ka hieroglyph replaces the images of food inscribed on offering tables.

Modern Balinese food offerings that look remarkably Egyptian

Kau, food offerings, provide life-energy for the individual ka. When the Egyptian offered food to her Deities or honored dead, she was offering the ka energy of the food to the ka of the Deities or ancestors. The ka inherent in the kau nourished the ka of the spirit being. Offering thus feeds the kas of the Deities and ancestors and the great pool of ka energy to which all enlivened things are connected. Simultaneously, the great pool of ka energy is the source of the energy found in the offerings by virtue of the ongoing, archetypal connection with it. By making and receiving offering, a great reciprocal power system was set up and could be eternally maintained. No energy was ever lost; it was continually transformed and re-activated by being offered and received, received and offered. Ka energy may be considered the food that fuels the engine of the universe.

Offering table piled high with kau and other offerings

Since offerings are given and received ka to ka, it is no wonder that the Egyptian who made offering before the sacred images in the temples, did not expect the Deity to physically consume the food or drink offered. Instead, she expected the Deity’s ka, residing within the image, to take in the energy from the kas of the offerings. Ancient texts are explicit about this. A text from Abydos says that the pure, Divine offerings are given daily “to the kas” of the temple Deities. Sometimes the Deities are said to have been “united” with Their offerings. It is the ka of the offering and the ka of the Deity that unite. In another text from Abydos, the king asks the Deity to bring His magic, soul, power, and honor to the offering meal. Clearly, the king is not expecting a physical appearance, but a spiritual one.

It is the same with our offerings. We offer the ka of the kau to Isis and Her ka receives it. We can open our awareness to this aspect of offering by envisioning the ka, perhaps as Light, move from the offering to our sacred image of Isis (if we are using one) or to an image of Her we hold in our mind’s eye. In this way, we can know that Isis has indeed received what we offer to Her.

A modern offering table

Filed under: Goddess Isis Tagged: Ancient Egypt, Egyptian ka, Egyptian offerings, Egyptian Temples, Goddess, Goddess Isis, Goddess worship, Invocation of Isis, Isis Magic, Isis worship today, Ka, Ka statue, Kau food offerings, Offering rituals, offering to Isis, Priestess and Priest of Isis, priestess of Isis, Ritual, The Goddess, Who is Isis?, why worship and how

May 25, 2015

Isis in Diaspora

A beautiful Isis-Sothis-Demeter from Hadrian’s villa, now in the Vatican Museums

Last week we talked about Isis devotees outside of Egypt.

But how did there come to be devotees outside of Egypt anyway? How did the worship of an Egyptian Goddess move out of Her homeland and into the greater Mediterranean world?

This is such an interesting puzzle for scholars in many disciplines, from history to religion to sociology, that it has actually been studied quite a bit. But what about those of us who are not historians or religious scholars or sociologists. Why care? Why not just say ‘it is what it is’ and call it a day? Does knowing how Isis’ worship spread make any difference at all to modern Isiacs?

For me, it’s about knowing our history. Those of you who know my work with Isis, know that I have no problem with innovative personal expressions of spirituality. Our relationship with Isis doesn’t have to look like anyone else’s. Nevertheless, Isis is a Goddess with a tradition. And like all living traditions, it has grown and changed over the millennia. If we are to be educated Isiacs, it’s important for us to know about those changes and developments.

This question also bears on Who we think Isis is. Once She leaves Egypt’s borders, does She became a different Goddess? Most certainly Iset began to look more Hellenized as Her worship spread. But for me, that is merely a matter of form, not essence. I’ve written about that here. And also here.

Isis with sistrum and bowl of fruit between female and male sphinxes, from the temple of Palatine Apollo

But today I’d like to look at that crucial period when Isis moved out of Egypt, how that may have come to be, and how, as a consequence, Isis earned Her epithet, the Many-Named.

First of all, we must remember that even within Egypt itself, Isis was already being joined with many other Goddesses; this is sometimes called “syncretism.” The natural fluidity of Egyptian Deities made this easy. Deities could combine—Osiris-Re, for example—or one could be the ba of another. Isis and Osiris were not just local Egyptian Deities, either. By the 5th century BCE, Herodotus could note that They were the only Deities worshipped throughout Egypt. And although Isis was known outside of Egypt even before this time, it was about then that Her tide began to rise. By the time of Ptolemaic rule in Egypt, it was surging.

But Isis was not the only one. There was a lot of religious movement at the time. Mysteries like those at Eleusis began drawing international crowds. Thracian, Syrian, and Jewish cults were seen in cities throughout the Greco-Roman world. And as they moved in, there were periods of both rejection and acceptance.

A Ptolemaic queen wearing the Isis Knot and sheer draperies

When rejected, the new types of worship were seen a deviations from the civic norm and thought either exotic, ridiculous, or horrible. Throughout Isis’ history in Italy, Her worship was rejected a number of times. But it also had periods of high-ranking patronage.

When accepted, we often see the “new” Deities being “translated” for Their new audiences. Since Hellenism was the dominant culture, the non-Greek Deities were translated into Greek—in names, symbols, and forms—so that They could be better understood by the local populations. Isis is like Demeter. Demeter is like Isis. To further explain the harmonies between the Deities, people might transfer symbols. Isis might be shown holding shafts of wheat, for example. That wasn’t in Her Egyptian iconography, but She is connected with grain and the grain cycle in Egypt and so it made sense to show Her in that way so that people could know at least something about Her.

Some aspects of the spread of Isis’ worship seem to have been quite natural. Egyptians who traveled to or settled in other parts of the world brought their Goddess with them. For instance, we know that Athens’ rulers had allowed an Isis temple to be built in the Piraeus “at the request of the Egyptians” sometime in the late 4th century BCE.

Terracotta figurines of Isis-Aphrodite, now in the Louvre

In an article I’m reading right now by Greg Woolf, he makes an interesting suggestion as to why Isis may have been singled out by Greeks “from the dense web of Egyptian myth and ritual for particular attention.” In addition to Her prominence in Egypt and the pathos of the Isis-Osiris myth, Isis’ sheer proximity may have been a factor. Her cult center at Isiopolis in the Egyptian delta was readily accessible to visitors from throughout the Mediterranean. (Having named this site “Isiopolis,” that idea pleases me.)

Other aspects of the diffusion of Isis’ worship seems to have been more purposeful.

When Alexander, who conquered Egypt in 332 BCE, was laying out the plans for his new capitol at Alexandria, he specified the number of temples that should be built and to which Greek Deities. He also personally marked the location for “a temple to the Egyptian Isis.” This was clearly a political move. Alexander wanted to placate his Egyptian subjects by including a temple to one of their most popular Deities in his new city. He chose Isis. By doing so, Alexander both recognized Her prominence in Egypt at the time and set the stage for Her prominence throughout the Mediterranean world in the future.

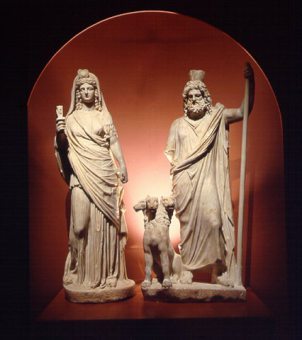

Hellenized Isis and Serapis, in Their chthonic aspects, now in the Heraklion Museum in Crete; yes, Their puppy is Cerberus

Alexander’s successors, the Ptolemies, the Macedonian Greek dynasty that ruled Egypt from 305 BCE until Rome conquered Egypt in 30 BCE, continued the promotion of Isis, as well as Her new consort Serapis. (You can read more about Serapis in Edward Butler’s excellent article here.)

As we have already seen, a number of the Ptolemaic queens associated themselves with Isis and most likely are the source of the famous knotted robes seen in later images of Isis and Her priestesses. Oh, and the Ptolemies built Egyptian temples—lots of temples. For the most part, these are the temples we still see today in Egypt.

At the time of the Alexandrian conquest, Memphis was a key Egyptian city. It is likely that Egyptian priesthoods there assisted in this translation of Isis to the rest of the Mediterranean. The famous Isis aretalogies, which include both Greek and Egyptian elements, were said to have been copied from an original text at Memphis. It is likely that the aretalogies (along with other hymns and praises of Isis) depicting Isis as both all-powerful and kindly were part of a program of evangelization.

Yet it is not as simple as Ptolemaic political promotion of the Egyptian Deities. Scholars who have studied this extensively have rejected that too-simple explanation repeatedly.

Isis Fortuna with Her rudder and cornucopia

According to one idea of how religions spread, any new religion must be able to fit within existing structures yet it must also offer an element of risk. In other words, it must offer something new and exciting, while at the same time being able to fit within people’s existing ideas.

With Isis’ Hellenization, Her worship was able to fit in. Each time Isis was translated to local people through the Goddesses they already knew, She added to Her list of names and epithets. We specifically find such equations in hymns like those by Isidorus of the Faiyum, in the , and in Lucius’ prayer in The Golden Ass.

Yet Isis also offered something different. She was Egyptian and exotic. Her rites—especially when they were re-Egyptianized as Her worship came to Italy—were very different than Greek and Roman civic rites and could be quite emotionally exciting. She even developed Mysteries in the Greek mode, which provided a very personal experience of the Divine. Even so, these new Mysteries were merely another way of expressing Her eternal and essential identity as a Goddess of birth, death, and rebirth.

For many, it made Her irresistible. And it is because Isis made this transition out of Egypt that so many still know Her today.

Filed under: Goddess Isis Tagged: Aspects of Isis, Hellenic Isis, Hellenistic Isis, Isis, Isis Fortuna, Isis in Athens, Isis in Rome, Isis Magic, Isis-Aphrodite, Osiris, Pagan Spirituality, Roman Isis, Sarapis, serapis, The Goddess, Who is Isis?

May 17, 2015

Isis Devotees & Initiates, Outside of Egypt

Isis from a temple in Macedonia, 2nd century BCE

Sadly, most of Isis’ devotees today are no longer in Egypt. Instead, happily, they are spread out across the globe.

Yet, this diffusion of devotion to Isis is really nothing new; it was part of the ancient world as well. Well before Egypt’s conquest by Alexander, we see devotion to Isis outside Egypt’s borders.

Even during archaic times (800 BC – 480 BC), we see traces of devotion, such as inscriptions or votive images. By the late 4th century BCE, Greeks in the Piraeus, Athens’ port city, had built a temple for Her there. At about that same time, the oldest of three Isis-Sarapis sanctuaries on the Greek holy island of Delos were established. We have evidence of Her worship in Crete from the 3rd or 2nd century BCE.

Sacred image of Isis from Brexiza, Greece, near Marathon

From the beginning of Ptolemaic rule in Egypt to the Roman period, devotion to Isis spread quickly throughout the Mediterranean and then, with the Roman Empire, broadly. As we saw in last week’s post, there was even an Isis temple in London, Roman Londinium. And this is really just the beginning. provides a long list of where She was worshipped and under what epithets.

Greek parents began giving their children names that included Hers at about these same times. Scholars generally agree that when we see an upswing in what are known as theophoric names (“Deity-Bearing” names; for instance, “Isidora” is a theophoric name), we are witnessing an increase in the Deity’s popularity as well. In Greece, we see a few Isis-bearing names in the 3rd century BCE, many in the 2nd century BCE, then an absolute explosion of Isis names from the 1st century BCE through the Roman Imperial period.

Perhaps even more interesting is that people may have taken names that included Hers as a sign of their devotion. This is not so different today. My own theophoric name is a taken name that I legally changed to permanently connect me with Her. And I know I’m not the only one.

Funerary relief of Sosiba in the dress of Isis, from Attica

Isis may have been especially important in Miletus, an ancient Greek city in what is now Turkey. There are five women, known from their funerary reliefs, who all bore the name Isias (or Eisias) and had come to Athens from Miletus. Some scholars have suggested that these women may have been former slaves who were freed in the name of Isis and therefore took the name of their deliverer. Others have suggested that they were initiates of Isis who took Her name—or that they may have been both.

The five Isis-named women in Athens were shown on their grave reliefs in the famous “dress of Isis,” that is, the fringed mantle with Isis knot, and holding the sistrum and situla. But theirs were not the only examples. In fact, we know of 108 such Attic reliefs of women and some men with Isis attributes; the women wear the Isis-knotted dress, while the men hold the sistrum and situla. During the Roman period in Athens, this number makes up one-third of all the known (and published) grave reliefs. If that number reflects true percentages rather than just chance, that’s an awful lot of Isiacs.

Funerary relief of Alexandra in Isis dress, from Roman-era Athens

In addition to the possibility that these Isis-accoutered people were initiates of Isis, it has also been suggested that they may have either been priest/esses, had a priest/essly function, or may simply have been especially enthusiastic devotees; for example, volunteers who helped maintain the sanctuaries and participated in the rites.

Or they may have been members of religious associations, like the thiasoi I mentioned last week, which were connected with the sanctuaries and served both a religious and social function. We know of one such group in particular that was connected to one of the Isis-Sarapis sanctuaries on Delos. It seems likely that enthusiasts would be members, or even founders, of such associations.

People could also stay for a time at the temples. In Apuleius’ tale of initiation into Isis’ Mysteries, prior to deciding to be initiated, his character Lucius simply spends time in Isis’ sanctuary:

“I took a room in the temple precincts, and set up house there, and though serving the Goddess as layman only, as yet, I was a constant companion of the priests and a loyal devotee of the Great Deity.” (Book XI, 19)

I wish he had described what specific things he, as a layperson, was allowed to do to serve the Goddess.

He does describe in part the morning rites, to which the public seems to have been welcomed:

A reconstruction of the Temple of Isis, Pompeii

“I waited for the doors of the shrine to open. The bright white sanctuary curtains were drawn, and we prayed to the august face of the Goddess, as a priest made his ritual rounds of the temple altars, praying and sprinkling water in libation from a chalice filled from a spring within the walls. When the service was finally complete, at the first hour of the day, just as the worshippers with loud cries were greeting the dawn light…” (Book XI, 20)

From the evidence we have from Greek Isis sanctuaries, it seems that the Greeks used priest/essly titles they were familiar with, but with adaptations to fit Isis’ mythos. We have records of a hiereus, a priest, a stolistes, one who adorns the sacred image of Isis, a zakoros, an attendant, a kleidouchos, a key bearer, and a melanophoros, a bearer (or wearer) of the black garments—Isis’ black garments of mourning. We can expect that Isis received offerings of food and drink, as did native Greek Deities.

A Hellenistic bracelet with two busts of Isis, made in Egypt

We have mentions from several Roman writers about devotions to Isis. The poets Propertius and Tibullus complain of the period of sexual abstinence their mistresses undertook for Isis. Ovid writes of the crowds of penitents at the temple of Isis. Tibullus also mentions a ritual called votivas reddere voces in which devotees could join in the singing of the virtues (aretai) of Isis in front of Her temple twice a day. (I wonder if they used any of the aretalogies of Isis we know of.)

A Renaissance statue of Isis by the sculptor Andrea Bregno, in the style of ancient Rome

Interestingly, when Isis comes to Rome, Her Roman worshippers seemed to have tried to make Her worship more “Egyptian” than did Her Greek worshippers. For instance, Roman Isis temples celebrated the rising of Sothis. They added back Egyptian symbols, such as the divine animals: crocodile, baboon, and canine. We see the development of lifelong priesthoods, something done in Egypt, but not done in Greece. Some Roman emperors may have especially appreciated the Egyptian relationship between Isis the Throne and the pharaoh. And it is in Italy that we first see priestesses of Isis rather than just priests.

For modern devotees, knowing the ways in which our spiritual ancestors honored Isis can inspire us in developing our own ways to honor Her. Whether we make offerings of food upon Her altar, pour libations of milk and wine, or sing of Her aretai before our shrines, we honor the Goddess Who fills our hearts and we connect with those who have gone before us.

Filed under: Goddess Isis Tagged: Ancient Egypt, Apuleius, Goddess Isis, Goddess worship, Greek and Roman images of Isis, Isis in Greece, Isis in Roman Empire, Isis in Rome, Isis Magic, Isis worship today, SunFest 2010, Who is Isis?

May 10, 2015

Sacred vessels of Isis

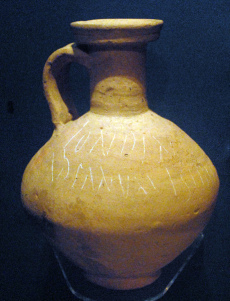

“To London, at the temple of Isis”

There is a very famous jug found in what is now Tooley Street in the Southwark borough of London. It doesn’t look like much; it’s about a foot high, just terracotta, with a graffito scratched on its surface. The jug is dated to the latter part of the 1st century CE.

It’s important because of what that graffito says. It says,”LONDINI AD FANVM ISIDIS,” that is, “To London at the temple of Isis”. Thus it confirms the existence of a temple of Isis in ancient London. One more reference to the temple has been uncovered locally as well. It’s a 3rd century CE altar (which had been used as part of a wall) with an inscription that states that the Isis temple had fallen down due to age, but had now been restored.

Together, these finds are the only certain evidence of an actual Isis temple anywhere in Roman Britain. (There are other artifacts—figurines, hairpins with Her image—that indicate Her presence in London, but nothing else about a temple.)

An Italian terracotta showing Isis with Harpocrates and Anubis. Her London devotees may have owned similar votive images.

The jug has been presumed to be a wine jug that may have belonged to a tavern near the temple, perhaps even a tavern dedicated to Isis. There is archeological precedent for taverns being located near temples as well as for being dedicated to Deities.

Other scholars have wondered whether the jug may have belonged to the temple itself. In particular, some have suggested that it may have been part of the feasting that would take place at temples by the religious associations who tended them. There is precedent for this, too.

Back in Egypt, demotic texts speak of “Days of Drinking” that became a term for the meetings of such groups. In Egypt, the groups were probably influenced by Greek symposia, meaning “drinking together,” and thiasoi, which were voluntary religious associations like our modern covens as well as larger organizations like the Fellowship of Isis. Yet there was native tradition, too. A scholar who studied this believes that the demotic name, Days of Drinking, may derive from one of the ancient Egyptian lunar festivals, which would no doubt include feasting and drinking as well.

A model of Londinium in the 1st century CE, from the London Museum

Such an association of Isiacs would not have been out of place in Roman London. We find them throughout the Empire. Archeologists have also found several other jugs inscribed with Isis’ name from other parts of the Empire.

I haven’t been able to find out whether anyone has actually tested residue from the Southwark jug to discover if it ever contained wine, but it sure looks like a classic wine jug—whether for use as part of the religious festivals at the temple or by the tavern next door.

The Southwark jug is, of course, not the only vessel with which Isis is connected. By the Late Period, She is especially associated with what is usually referred to as a situla, a container for sacred liquids. Many representations of Her show a sistrum in one hand and a situla in the other, some of them conspicuously breast-shaped.

An Egyptian situla or washeb

The situla is not exclusive to the religion of Isis. From approximately the 19th dynasty onward, these small ritual buckets, washeb in Egyptian, were used to carry offerings of Nile water or milk in the cults of many Egyptian Deities. A text from Denderah that describes rites for Osiris specifically mentions a “situla of gold.” Situlae were usually decorated with scenes involving fertility, nourishment, or the cult of the specific Deity for Whom there were being used.

Scenes on the situale might include images of the nurturing Cow Goddess, images that suggest fertility, such as the plump Nile God or a Child God on a lotus, or sexual images such as the ithyphallic God Min. It seems clear that the breast or womb-like vessel was associated with the nurturing, fertile, and sexual aspects of the Divine—and thus very appropriate to Isis.

While the situla is spoutless, a different type of spouted vessel is also connected with Isis. It is the urnula or hydreion. It is from a later period and found in Isiac representations outside of Egypt.

Roman priestesses and priests of Isis; urnulas are carried by the priestesses on the right and left, situlae are carried by the priests

Nonetheless, it was always made to look Egyptian, decorated with Egyptian scenes and hieroglyphs and usually with a rearing cobra on the handle. The urnula was specifically for carrying sacred water, especially sacred Nile water. We don’t know for certain, but it most likely was used to pour libation offerings to the Goddess. In Apuleius’ novelized account of initiation into the Mysteries of Isis, he says that the vessel “represented the Highest Deity.”

A charming vessel in the shape of mother and child; it held human milk, which was used in healing medicines

I have argued in Isis Magic, that Isis is one of the Great “Container” Goddesses, that is, one of the Great Mother Goddesses Who Contain All Things.

The concept of the Mother as Great Container is easy to understand. Like the human mother who contains the child and, once born, the milk to nourish it, the Great Mother contains all creatures and provides sustenance for them through the blessings of nature. Judging by the numerous gynomorphic vessels that have been found throughout all regions of the world, the concept of Great Mother as Container of All appears to have been common throughout the prehistoric world.

So, from a specific Isiac vessel, we can take our exploration of Isis to an expanded and more symbolic level. She is at once the Goddess celebrated in feasting and drinking together and She is the Lady of the Vessel and the Great Vessel Herself. She is the All-Containing One Who gives us life and nourishment, in life and in death.

Filed under: Goddess Isis Tagged: Ancient London, Aspects of Isis, Egyptian Temples, Goddess Isis, Goddess worship, Isis, Isis in London, Isis Magic, Isis Rituals, Roman Isis, Situla, Southwark Isiac jug, Temple of Isis London, The Goddess, Urnula, Who is Isis?

May 3, 2015

Isis of the Winds

Isis, Mistress of Wind

We have seen how Our Goddess is a Lady of Fire and of Water. Today, we take a deep, cleansing breath and honor Her as Lady of the element of Air—of Breath, of Wind, and thus of Spirit.

Indeed, many cultures associate breath, air, and wind with Spirit. For while these things are invisible, they are invisible Powers, and we are intimately touched by their influence. We breathe the air and we live. The wind fills a sail and we move. Wind, air, and breath thus can be seen as manifestations of the invisible powers of the Deities.

Perhaps that is why my favorite title for an Egyptian book of the dead is the Book of Breathings. It is the book “which Isis made for her brother Osiris, to make his ba live, to make his body live, to make young all his members” and it especially emphasizes the importance of breath for resurrection. The Lady of the Breath of Life fans Her wings and puts “wind” into Osiris’ nose. The God lives and His Divine Spirit revives when He “smells the air of Isis.”

In Isis, breath, air, and wind are one.

In the Book of Coming Forth by Day, Isis declares that She comes “with the north wind.” The Goddess and the wind were associated because both were known to bring the cooling, life-giving waters of the Inundation. It was thought that the north wind “dammed up” the Inundation, which flowed from the south, enabling the water to flood and nourish Egyptian fields. So Isis is not only the one Who heralds the Inundation and causes it to flow (as Iset-Sopdet), but Her northerly winds also keep it in place so that it will water and fertilize the fields.

A fanciful Italian mosaic, from the Hellenistic period, showing Egypt during Inundation

As Iset Mehit, Isis of the North, and Lady of the North Wind, the Goddess brings the sweet-smelling north wind and all good things. Temple texts at Edfu identify Her with the “good north wind.” In the Book of Hours, She is the “living north wind.” Isis is especially found whenever air is active, whether in beating wings or gusting winds; there was even a Hurricane Isis several years ago. (This year, they removed that name from the eligible list due to current associations that shall not be named.) Some stories describe Her mourning cries for Osiris as the wailing and moaning of the winds.

Today, the wind provides power in Egypt; this is the Zafarana wind farm

Isis can be a controller of the winds, too, for it is She Who promises the king in the Pyramid Texts (Utterance 669), “the south wind shall be your wet nurse and the north wind shall be your dry nurse.” The wind or breath of Isis can also purify. In the Pyramid Texts (Utterance 510), the deceased is cleansed with a vessel “which possesses the breath of Isis the Great.” In a work by the Roman writer Lucian, Isis is invoked to send the winds.

In the myth of the Contendings of Horus and Set, when the Ennead finally rules in favor of Horus to succeed His father Osiris, Isis sends the north wind—which She both controls and personifies—to bring the good news to Osiris in the underworld.

Isis can also be connected to other directional winds. In the Book of Coming Forth by Day (Chapter 161), the four winds are attributed this way: Osiris is the north wind, Re is the south wind, Isis is the west wind, and Nephthys is the east wind. All of them enter the nose of the deceased and bring her or him life.

Elemental de Aire by Ades21 on Deviant Art

Isis is not the only Deity associated with the winds and air, of course. Wind is also the manifestation of Amun, the Hidden One, of Shu, the God of Air and Light, and of Atum, the Creator. In the Book of Coming Forth by Day, an otherwise unidentified “Great Goddess, Mistress of Winds” brings benefits to the deceased. In the Coffin Texts, the deceased calls himself “Mistress of the Winds in the Island of Joy.” Another tells us that the deceased receives the breath of life from four primordial Maidens associated with the four winds and Who existed “before men were born or the gods existed.” (Formula 162.)

The deceased holds a sail to catch the breath of life

The Book of Coming Forth by Day sometimes shows the deceased holding a sail to catch the breath of life. Since the dead are identified with Osiris, it would make sense that the sail is intended to help them magically catch the air fanned into the dead by the powerful wings of Isis.

In a later period, images of Isis Pharia show the Goddess Herself holding a sail. The billowing sail of Isis Pharia ensures smooth sailing on the seas as in life. Perhaps this later image harks back to Isis’ more ancient attribution as She Who fills the sails of the dead with breath and life.

In Graeco-Roman texts of about the same period as the Isis Pharia images, Isis “hast dominion over winds and thunders and lightnings and snows” and She declares in one of Her aretalogies, “I am the Queen of rivers and winds and sea.”

Isis Pharia with Her sail and the lighthouse on the right

A second-century-CE papyrus found in Oxyrhynchus, Egypt calls Isis the “true jewel of the wind and diadem of life.” A hymn at the Goddess’ Faiyum temple connects Her with the winds, too: “Whether you have journeyed to Libya or to the south wind, or whether you are dwelling the outermost regions of the north wind ever sweetly blowing, or whether you dwell in the blasts of the east wind where are the risings of the sun…”

In whichever wind She dwells, Isis is always the ancient Lady of the Living Air, Queen of the Winds, Winged Goddess of the Spirit Revivified. From Her we receive our breath and our life.

Filed under: Goddess Isis Tagged: Ancient Egypt, Aspects of Isis, breath, Egyptian magic, Goddess, Goddess Isis, Goddess worship, Mistress of Wind, Osiris, spirit, The Goddess, Who is Isis?, Wind

April 26, 2015

Isis & Tolerance

I’ve been reading too much Patheos, lately. And not the Pagan blogs either; the Christian ones. The comments; yikes! If we’ve got that kind of controversy among people of (ostensibly) the same religion, how are we ever going to coexist with each other cross-religion. (One writer was horrified! horrified! that the “coexist” sentiment had come home from school with a little girl in his bible study.)

But guess what? Religious tolerance is hard.

And it always has been. Even in a polytheistic world where people were used to dealing with a variety of religious expressions.

And it always has been. Even in a polytheistic world where people were used to dealing with a variety of religious expressions.

For instance, Greek comic playwrights often made fun of the religious practices of Egyptians, usually focusing on their reverence for animals as manifestations of the Divine. This 4th-century-BCE bit by Anaxandrides of Rhodes, who won many awards for his work, is an example. He writes as Demos (“the people”) to Egypt:

I couldn’t have myself allied with you. Our ways and customs differing as they do. I sacrifice to Gods; to bulls you kneel. Your greatest God’s our greatest treat: the eel. You don’t eat pork; it’s quite my favorite meat. You worship your dog, mine I always beat when he’s caught stealing. Priests stay whole with us; with you they’re gelded eunuchs. If poor puss appears in pain, you weep; I kill and skin her. To me, the mouse is nought, you see ‘power’ in her.

Some Egyptians, on the other hand, considered Greeks whipper-snapper-know-nothings when it came to religion and declared that anything that came out of a Greek mouth was just a lot of hot air.

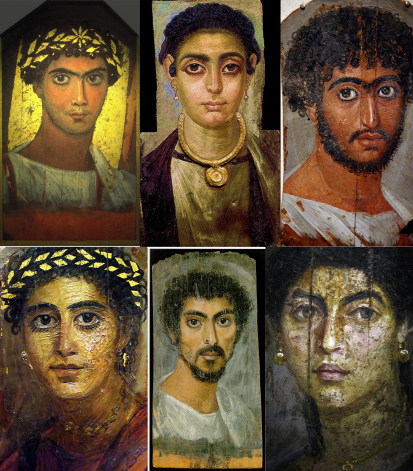

Mummy portraits from Egypt’s Fayoum, an area where Greeks and Egyptians mixed freely and intermarried

Religious tolerance is hard precisely because our religion, our Deity or Deities, our practices, our beliefs and experiences are so close to our hearts. In many cases, they are cherished building blocks of our lives. If religion is central to our lives, it is also likely to be central to our self-definition. If someone attacks (or, in some cases, even questions) our religion, it seems they are attacking our core self. That not only hurts on a feeling level, it actually seems life-threatening. The chest tightens as the heart speeds up. Nerves jangle. The belly feels sick. Fight-or-flight kicks in—and we often find ourselves coming down on the side of fight. I know I’ve been there, too.

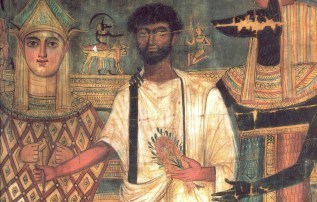

A painting on a funeral cloth from Saqqara Egypt, 180 CE

Yet, as far as I know, no wars were fought over Greek and Egyptian religious differences. The grandfather of Lycurgus (an Athenian politician from 338-326 BCE) may have been influential in bringing the Egyptian religion of Isis to Athens. Apparently his grandson suffered no discrimination on account of his family’s connection with Egyptian cult—apart from the jabs of the comics. Ancient priestesses and priests often simultaneously served very different Deities without betraying any of Them. The historian Herodotus was able to casually say that Isis “is called Demeter by the Greeks.”

That kind of syncretism, which happened to an astonishing degree with Isis, is one of the ways the ancient religion of Isis modeled religious tolerance. It wasn’t a matter of my-Goddess-is-better-than-your-Goddess; it was a translation of the Goddess from one culture to another. In the bustling world of the Mediterranean, people were used to translating languages. Why not translate Deities? And so they did. And so Isis became known as Isis Myrionymos, Isis of the Myriad Names. In Isis, with Her uncountable number of names, people could see THE Goddess—in all Her many expressions. Isiacism also modeled social tolerance in its acceptance of both women and men, rich and poor, slave and free. In late Isiacism, there was even a tradition of the freeing of slaves through a “sale” to Isis and Sarapis. Freedom and tolerance go hand-in-hand.

I like this a lot

The modern Fellowship of Isis maintains this type of wide-open religious tolerance. All one must do is to be able to accept the organization’s Manifesto to become a member. To some, this tolerance may seem too chaotic, too accepting; yet it has enabled this modern group to survive for many years, even as it has suffered through the types of internal struggles to which all groups seem inevitably subject.

But how can we maintain the virtue of tolerance when faced with intolerance from others? What do we do when accused of “devil worship,” like the Isis devotees accused by some early Christians of Alexandria of worshipping “a dark, Egyptian devil?” How do we handle the current intolerance-based horrors in the Middle East? Or, on a much less deadly but sometimes quite hurtful level, how do we navigate the Neo-Pagan community’s current growing pains as groups of people seek to differentiate themselves from (though I would hope within) the greater community? I’ve been surprised at the lack of tolerance I’ve seen in some of the discussions. But I guess it gets back to that ‘close to the heart’ thing.

Oh, how I wish I had an answer.

Friends and I sometimes play a game in which we choose one thing to change about the world and discuss the implications of that change. True religious tolerance is the magical change of heart that I often wish upon the world. By no means would it solve the world’s problems (poverty, war), but it might just give us enough space to get our heads out of our asses above water long enough that we could at least start to solve them.

Religious tolerance isn’t easy. In some cases, it doesn’t even seem possible. But that doesn’t mean we give up. We take some deep breaths. We remember that Isis lives. We explain it; again. Sometimes we walk away from an un-winnable argument. And we work for civil justice.

Filed under: Goddess Isis Tagged: Aspects of Isis, Deities, Goddess, Goddess Isis, Isis Magic, Religious Tolerance, Tolerance

April 19, 2015

The Great Mother & Her Mother & Her Mother’s Mother

Isis the Mother

Not too long ago, a friend of this blog asked a very interesting question. She asked how we can reconcile the idea that Isis is both Mother of All with the idea that Isis has a mother Herself. It’s a question I’ve been wanting to work on ever since it was asked, so with this post I’m finally getting around to it.

It’s a very interesting question because it has to do with our conception of the nature of the Divine and Divine Beings in general.

So how do we start to look at this?

For me, history is always a good place to begin. It gives us a useful foothold to know what our ancestors thought about these things; after all, when it comes to Divinity and Divine Beings, we human beings have been thinking about this for a very long time indeed.

Atum arises from the Nun, the primordial waters of No-Thing-Ness

Erik Hornung’s Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt, the One and the Many is a key text for understanding the nature of the Divine in terms of ancient Egypt. Hornung writes that the Egyptians had a multiplicity of approaches to the Divine and only when taken together can we see the whole picture. For them, he says, everything came from One because the non-existent is One, Undifferentiated Thing. Once something becomes existent, it also becomes multiple.

We see this in the Heliopolitan myth in which Atum comes forth from the Nun, the non-existent, the inert, and immediately begins generating other Deities through an act of masturbation: first Shu and Tefnut, Who beget Nuet and Geb, Who beget Isis, Osiris, Set, and Nephthys.

And so we meet Isis, Her mother Nuet, and Her mother’s mother Tefnut. And there may even be a great grandmother present, for when Atum came into existence, He was both masculine and feminine; His “shadow” or “hand” (the one He used to masturbate) is the Goddess Iusaaset or Iusâas Who is said to be the Grandmother of all the Gods.

The Ennead of Heliopolis

Another important characteristic of the Divine in ancient Egypt is Its fluidity. Hornung says of the Egyptian Deities, “They are formulas rather than forms, and in their world, one is sometimes as if displaced into the world of elementary particles.” Deities may be combined with one another or split off from one another; one Deity can be the ba or soul of another; They can even be assimilated with foreign Deities without losing Their essence. “But wherever one turns to the divine in worship, addresses it and tends to it in cult” Hornung writes, “it appears as a single, well-defined figure that can for a moment unite all divinity within itself and does not share it with any other god.”

Mother Isis, nursing Horus and protected by the Vulture Mother

The primordiality of Isis is attested on the Great Pylon of Her graceful temple at Philæ. The Ptolemaic passage states that Isis “is the one who was in the beginning; the one who first came into existence on earth.” In the Coffin Texts, Isis is invoked with a group of Deities considered to be the most ancient: “O Re, Atum, Nu, Old One, Isis the Divine…” (Formula 1140). She is called Great Goddess Existing from the Beginning, Great One Who Initiated Existence, and Great One Who Is From the Beginning. Her very name, Iset or Throne, speaks to Her ancient nature.

By the time of the New Kingdom, Isis is routinely called Mother of All the Gods. Then, with Her worship spreading throughout the Mediterranean and beyond, Apuleius can write that Isis “brings the sweet love of a mother to the trials of the unfortunate,” while a Latin dedicatory inscription sums up Her all-encompassing nature: Tibi, Una Quae es Omnia, Dea Isis, “Unto Thee, the One Who art All, Goddess Isis.”

So now we have ancient attestations both of Isis’ primordiality and of Her generation from Her parents, grandparents, and great grandparents. How do we resolve it?

Which came first? It’s a paradox.

If we are among those who are uncomfortable with paradox, I’m afraid there may be no satisfying reconciliation between these two ideas. If it has been deeply ingrained that there can only be one right answer—especially when it comes to spiritual questions—then it may seem impossible for both these things to be true. After all, they contradict each other. At the very least, we should be able to pick one as the “right” answer. At the very most, we may decide the contradiction means both things must be false.

And yet we have already seen that, at least to the ancient worshippers of Isis, both things were indeed true.

This is what paradox is; and religion is absolutely rife with it. Why? Because most religions, or spiritualities if you prefer, involve Mystery. Mystery is at the very core of the Divine and paradox is one of Its favorite languages. Yet this is not to say we should simply throw up our hands up and say, “Goddess works in mysterious ways” and quit thinking about it.

Quite the opposite in fact. Paradox invites thought. It is intended to teach. So what can we learn from our paradox: Isis is Mother of All, yet She Herself has a mother?

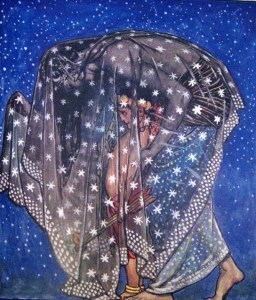

Originally an illustration for a book of pseudo-Indian love poetry called The Garden of Kama, this lovely illustration by Byam Shaw, 1914, captures something of Nuet caring for one of Her Holy Children

Let’s look at it through that ancient Egyptian lens that shows us a multiplicity of approaches to the Divine.

One way we can approach is as the Heliopolitan myth does: Isis is part of a Divine family. By being so, perhaps She is better able to understand human beings when we come to Her with our own familial problems. Her family relations make Her more suited to be a Soteira, a Savior Goddess, as She was known throughout the Mediterranean world.

We can also learn some important things about Isis through Her family relations. Isis is the daughter of Heaven (Nuet) and Earth (Geb). She is married to the Underworld God, Osiris, and is Herself a Goddess of the Underworld. Thus Isis is intimately connected to All That Is; She walks in all the Worlds.

Another approach to our paradox is through the fluidity of the Egyptian Deities that we talked about. If They can combine or split at will, or if one can become the ba of another, why can’t Isis be at once a Great Mother Herself and the daughter of a Great Mother?

Yet another approach is to open our hearts toward Isis in worship and experience Her for ourselves. Then, as Erik Hornung explained, Isis “appears as a single, well-defined figure that can for a moment unite all divinity” within Herself; She is the One Who is All, and She is the Mother of All.

By combining these approaches, and tolerating a little paradox, we learn more about Isis than we ever would have by restricting ourselves to a single position alone and Isis reveals Herself ever more as the Great Goddess She is.

Isis is all things and all things are Isis

Filed under: Goddess Isis Tagged: Ancient Egypt, Aspects of Isis, Atum, Geb, Goddess, Goddess Isis, Goddess worship, Heliopolitan Ennead, Isis, Isis Magic, Isis worship today, Nephthys, Nut, Osiris, Paradox, Set, Shu, Tefnut