Matthew Burden's Blog, page 5

September 5, 2024

Reflections on My English Pilgrimage, Part 3

This will be the last of my reflections on my English pilgrimage; next week the blog will resume its normal schedule of posts. While the previous reflections have centered on history and theology, this one is more personal, albeit with connections to the life of the church that I hope will prove edifying to my readers.

As with any pilgrimage, one of the goals was to seek out the presence of God and, hopefully, gain some experience to shed insight or inspiration on my walk with the Lord. One need not travel to England or Israel to gain that experience, of course--God is everywhere, and just as readily encountered in the woods around one's home as in Jerusalem. But the practice of pilgrimage can provide a focusing effect on one's seeking, an opportunity to step away from the pressures of home life and to pursue God in places that still ring with the stories of countless saints who have also encountered the living Lord there.

While I certainly hoped to encounter the presence of God in a way that would challenge, convict, and shape me in my road of discipleship, one of my main goals for this pilgrimage was also to try to figure something out about myself. As anyone with a passing familiarity with this blog has probably already noticed, I'm something of a fence-straddler when it comes to the old divisions between high-church and low-church forms of worship. I write essays about evangelical theology and post them alongside Eastern Orthodox icons; I write hymns in the Baptist tradition and liturgies hearkening back to Anglican and Orthodox forms. The truth is, I don't quite know where I fit. Who knows, it probably has something to do with my deep-running psychological formation as a TCK in my early childhood (which produces something of a sense of perpetual, journeying rootlessness in one's life). But in short, I've always loved the whole breadth of the Christian tradition and yet never felt entirely at home in any one segment of it. It may be that I, like many younger evangelicals, am drawn by the gravity and grandeur of the ancient forms of the faith, in what appears to be a common generational trend. But unlike many of my peers, I've never sought to make a move away from my home tradition and into another one.

Whatever the cause of it, this sense of belonging everywhere-and-nowhere in the Christian church has long been a part of my experience. I've been a Baptist most of my life, both by heritage and conviction, but I've also been blessed to have deeply formative experiences in the Anabaptist, Wesleyan-Holiness, Reformed, Anglican, Pentecostal, Catholic, and Orthodox traditions. I'm a committed Baptist pastor who is also, on the side, in fellowship with an Anglican apostolate and a Benedictine monastery. An odd duck, to be sure.

Whatever the cause of it, this sense of belonging everywhere-and-nowhere in the Christian church has long been a part of my experience. I've been a Baptist most of my life, both by heritage and conviction, but I've also been blessed to have deeply formative experiences in the Anabaptist, Wesleyan-Holiness, Reformed, Anglican, Pentecostal, Catholic, and Orthodox traditions. I'm a committed Baptist pastor who is also, on the side, in fellowship with an Anglican apostolate and a Benedictine monastery. An odd duck, to be sure.One of the ways this is expressed in my life is in the dichotomy between my worship with my home church and my worship elsewhere. My home church, where I serve as pastor, is my spiritual family, and nothing else comes close in that regard. It is irreplaceable. Nevertheless, if we were to look at the issue in the abstract and consider only the forms of worship involved, a striking pattern emerges: in my pastoral ministry, I worship in a low-church context; but on those infrequent occasions when I'm off on my own and the choice is mine, I almost always seek out high-church worship. I look for an Anglican high mass or an Orthodox Divine Liturgy to attend. I vary my customary worship--heartfelt praise songs, hymns, and extemporaneous prayers--in favor of more ancient forms: liturgies, collects, and creeds. While I'm gifted at leading low-church worship services, and truly enjoy them and find them spiritually fruitful, I had gradually come to believe that perhaps, if I were simply a worshiper and not a leader, I would feel at home in a high-church tradition. This was the hypothesis I put to the test in my English pilgrimage, but the results bucked my expectations.

Almost all of the worship services I attended in England were high-church services (usually of the Anglican variety). And I loved it. As I wrote last week, the most profound emotional and spiritual experiences of my entire trip came during high-church Eucharist services. But after a couple weeks of this, I found myself looking around for a nice low-church service I could attend. I was yearning for heartfelt praise songs and the warm personal connection of an evangelical fellowship. Maybe it was just that I had been away long enough to feel lonely and ready for a taste of home; I don't know. But God graciously provided exactly what I longed for, in the most unexpected way.

It was Saturday, and I had just left the conference in Oxford and was making my way toward Norfolk. I got off at a train stop in Peterborough to see yet another old cathedral. I wasn't attending worship in Peterborough Cathedral--not only did I not really feel like another high-church service at the time, but the cathedral itself had been redecorated as a children's museum instead of a place of worship (which was something of a letdown). Feeling bereft of God and longing for some worshipful singing and open-hearted prayer, I stepped back out of the doors of the church to hear a group of evangelical Christians singing together on the cathedral green. They were singing "Faithful One" (a worship song beloved in English evangelicalism, and one which has long been a favorite of mine). I sat down in the grass and sang along with them until they were told to stop by cathedral security guards. Then I went up to meet them and they prayed for me and my journey, and it was like drinking water from a deep, cool well. God had granted me just what I needed in that moment.

It was Saturday, and I had just left the conference in Oxford and was making my way toward Norfolk. I got off at a train stop in Peterborough to see yet another old cathedral. I wasn't attending worship in Peterborough Cathedral--not only did I not really feel like another high-church service at the time, but the cathedral itself had been redecorated as a children's museum instead of a place of worship (which was something of a letdown). Feeling bereft of God and longing for some worshipful singing and open-hearted prayer, I stepped back out of the doors of the church to hear a group of evangelical Christians singing together on the cathedral green. They were singing "Faithful One" (a worship song beloved in English evangelicalism, and one which has long been a favorite of mine). I sat down in the grass and sang along with them until they were told to stop by cathedral security guards. Then I went up to meet them and they prayed for me and my journey, and it was like drinking water from a deep, cool well. God had granted me just what I needed in that moment.So where does that leave me? Still fence-straddling, I suppose. No, something better than that. It emphatically did not confirm my hypothesis that maybe I secretly belonged in a high-church tradition as my spiritual home. I found that I couldn't do without the beauty of low-church worship either. So all this has convinced me that I will never be satisfied with anything less than the entire Body of Christ. My home is the whole church, every part of it. Wherever brothers and sisters are gathered, whether raising their hands in song or bowing in an ancient creed, I am no stranger there. From my Baptist church at home to the little Orthodox chapel I attend on vacations, I will take joy in all the ways that the Bride adores her Beloved. And perhaps that's as it should be.

August 30, 2024

Reflections on My English Pilgrimage, Part 2

The second set of reflections I've been ruminating on have to do with the Eucharist (that is, communion). If I had to look back and say which experiences most captivated me and produced the most profound spiritual effects in my interior life during the trip, they were all centered on the Eucharist. While I attended nearly as many church services as it is possible to attend while in England (many churches, following a pattern set down in the English Reformation, hold twice-daily prayer services and offer communion several times a week), three such experiences stood out to me: a communion service in the crypt of Canterbury Cathedral at the end of my walking journey across Kent, another at the high altar of Lichfield Cathedral on the Feast of the Transfiguration, and a third in the nave of Southwark Cathedral on my final day in England. In each case, the moments of consecration and reception in the communion liturgy struck me with raw and unexpected emotional power, in a way that has stuck with me over the succeeding weeks.

My own Baptist tradition celebrates communion on a monthly basis (which is itself a far more frequent schedule than some earlier Baptist groups would have offered), but I'm also connected with a few groups that make it the central feature of the church's weekly worship. The latter position, in my opinion, tends to accord best with the earliest practice of the Christian church, as witnessed in both the New Testament and the apostolic fathers. Most of the churches which now hold a weekly Eucharist tend to hew to a high-church, sacramental position, while those that offer communion more infrequently generally hold a low-church, symbolic view of the rite. And while many of the debates between these two wings of the church rotate around the question of whether communion represents the real presence of Christ (and if so, in what way), I'd like to draw attention to a different feature of the early Christian practice with regard to the Eucharist.

One of the curious features of the earliest post-NT accounts of communion liturgies is that none of them put significant stress on the institution narrative or the question of body/blood relative to the presence of Christ. That is, none of the mentions of Eucharistic celebrations from the late first, second, or early third centuries delves deep into the words of Christ at his Last Supper with his disciples, beyond the observation that he commanded this ritual. This is something of a surprise, since nearly all modern liturgies place their greatest attention on this aspect, and the interconnectedness of Communion and the Last Supper is clearly visible in both the gospels and the letters of Paul. So why the strange absence of a historical reference to Jesus's passion?

As I was looking over the earliest sources at the patristics conference, something struck me. When the Didache and Justin Martyr and Irenaeus speak about communion--all while strangely omitting the sort of body/blood reflections on the Last Supper which we would have expected--they all nevertheless do have a shared theme in common. Each of them connects the celebration of communion with the idea of creation, and often with a secondary connection to the idea of the New Covenant. The idea being presented, then, is this: that just as the Old Testament covenants with Noah and Moses were oriented around the presentation of sacrifices that represented the gift of created things being offered back to God, so the New Testament covenant is oriented around these symbols of New Creation: bread and wine, drawn from the stuff of creation but mystically representing the body and blood of Christ, who is himself the first instantiation of the New Creation. To eat the offerings of the Old Covenant (as was part of the ritual practice) was to gratefully accept the goodness of God's creation as our sustenance. Now, however, as human beings who have entered the New Creation through Christ's death and resurrection, we must be fed and sustained by the stuff of the New Creation--Christ himself. Since we belong to a new and different world, our spiritual sustenance comes from that world, from the work of God in New Creation, offered to us through Christ our Lord. As Irenaeus puts it, communion is "the new oblation of the new covenant" and "the means of subsistence, the first-fruits of his own gifts" (Adv. Haer. 4.17.5). This perspective undergirds the early Christian sensibility about the necessity of communion as a continuing part of Christian worship: we offer back to God the goodness of what he has given to us in a pure sacrifice (Mal. 1:11), and we then receive it as our food, the food of the New Covenant and the New Creation. Since Jesus himself is the first-fruits of that New Creation in a way that nothing else in creation is, it necessarily must be a representation of his own flesh which we consume. His body is so far the only physical element of the New Creation which has sprung forth into the world, and so if we are to offer and eat the fruits of New Creation (just like the old sacrifices offered the fruits of created things), it must be his body which is offered in the rite. We are being re-made as creatures of the New Creation, looking forward to the eschatological fulfillment of all things, and so we eat the bread of the New Creation in expectation of the fullness that is to come.

I'm not sure this particular perspective in early Eucharistic theology has really been properly considered by contemporary scholars, so it's something I'm continuing to think about. It may have further ramifications for our life in Christ, or it may not, but at the very least, it's certainly a point of interest. To receive communion is to take part in an eschatological sacrifice, a foretaste of the New Creation that is to come, and the Wedding Supper of the Lamb. And that is something worth reflecting on.

August 22, 2024

Reflections on My English Pilgrimage, Part 1

Part of the ruins of St. Augustine's Abbey, Canterbury

Part of the ruins of St. Augustine's Abbey, CanterburyIn thinking over my English pilgrimage, I have three sets of reflections that have been rattling around in my brain, and I'll share them here in a series of posts, this week and next. First, about Christianity and the West; second, about the Eucharist; and third, about my own relationship to the church. So for this post, I'm looking back at the story of Christianity's re-emergence in Britain in the early medieval period, and what a burst of light in the so-called "Dark Ages" can tell us about our own day.

As a scholar of church history, and with a particular focus on the history of missions in early Christianity, I wanted to explore sites associated with the re-evangelization of Britain in the seventh century. Re-evangelization, you say? Well, yes. Britain had already received the gospel before that date, back when the native Britons were under the sway of the Roman Empire, and several of the sites I visited attested to that ancient heritage. There was St. Alban's Cathedral, marking the spot where--according to tradition--the first Christian martyr in England was killed, sometime in the late third or early fourth century. And there was St. Pancras Old Church in London, marking an old Roman encampment where, some believe, the first Christian church in Britain was erected after Constantine's edict of toleration in 313 AD. This Roman Christianity spread through the local population, such that the Britons largely became a Christian people over the succeeding years.

But paganism was about to mount a swift comeback in Britain, and it came in the form of a settler-invasion: the Angles and Saxons, Germanic stock from across the North Sea, settling first in Kent and East Anglia and gradually sweeping across the island. By the time the late sixth century rolled around, the Britons had been pushed back into Wales, and all of what is now England was once again pagan, bereft of the gospel.

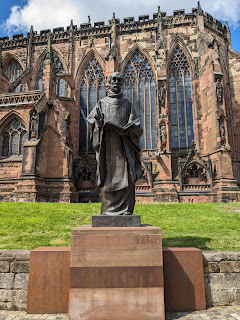

St. Chad, Lichfield CathedralIt's at this point that my interest in the story picks up, because England would be the beneficiary of two great waves of missionaries, coming from the south (Rome) and the north (Irish monks in Scotland). While only one of the sites I visited on this trip attested to the legacy of the Celtic monks from the north (Chad's preaching in Mercia, where Lichfield Cathedral now stands), many of them were associated with the surge of evangelization from the south. Both the Roman and Celtic mission movements were spectacular: in the seventh century AD, in a time when the transmission of people and information was far, far slower than it is today, the message of the gospel raced across the hills and heaths of England at an astonishing pace. One needs only take a look at the handful of cathedrals I visited to see the story in real time:

St. Chad, Lichfield CathedralIt's at this point that my interest in the story picks up, because England would be the beneficiary of two great waves of missionaries, coming from the south (Rome) and the north (Irish monks in Scotland). While only one of the sites I visited on this trip attested to the legacy of the Celtic monks from the north (Chad's preaching in Mercia, where Lichfield Cathedral now stands), many of them were associated with the surge of evangelization from the south. Both the Roman and Celtic mission movements were spectacular: in the seventh century AD, in a time when the transmission of people and information was far, far slower than it is today, the message of the gospel raced across the hills and heaths of England at an astonishing pace. One needs only take a look at the handful of cathedrals I visited to see the story in real time: - Canterbury Cathedral, built on a site sacred to the memory of the original Roman missionary to the Anglo-Saxons, Augustine of Canterbury, who arrived there in 597 AD;

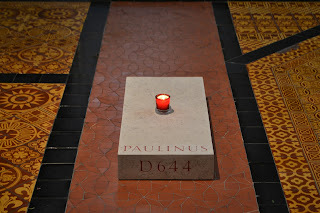

- Rochester Cathedral, marking the mission of Augustine's friend Justus, who planted the faith there just a few years later; and which cathedral is also the resting place of Paulinus, yet another member of the Roman mission team, whose ministry of evangelization in the early seventh century took him all the way northward, into York and Northumbria;

- St. Paul's Cathedral, which likely goes all the way back to the ministry of Mellitus, a fourth member of that same Roman mission team, consecrated by Augustine to plant a church in London;

- Christ Church Cathedral, marking a Christian abbey founded in the latter half of the seventh century by the Anglo-Saxon princess Frideswide;

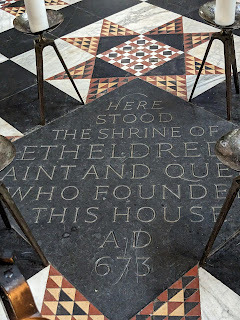

- Ely Cathedral, also founded as an abbey in 672 by the Anglo-Saxon princess Etheldreda;

- Lichfield Cathedral, marking the seventh-century ministry of Chad, who had pressed the Celtic Christian evangelization of England deep into the last remaining pagan territory, adding to the legacy of a whole generation of Celtic missionaries like Cuthbert, Aidan, and Mungo.

Memorial to St. Paulinus, Rochester CathedralAll that to say: many of the greatest churches of the land attest to a dramatic turning of the tides that came within the span of a single century. Britain had fallen from Christianity to paganism, and that violent conversion was, to all eyes, utterly complete. And then, in the blink of an eye, the whole thing was transformed completely, and the gospel made its second passage across the land in a way that transformed Britain entirely. It was a startling turn of events, and not by any means a guaranteed outcome--some of the other Germanic peoples of central, eastern, and northern Europe would take another half-millennium to fully convert to the Christian faith. Something swift and striking was afoot in seventh-century England, and it gives me hope for today.

Memorial to St. Paulinus, Rochester CathedralAll that to say: many of the greatest churches of the land attest to a dramatic turning of the tides that came within the span of a single century. Britain had fallen from Christianity to paganism, and that violent conversion was, to all eyes, utterly complete. And then, in the blink of an eye, the whole thing was transformed completely, and the gospel made its second passage across the land in a way that transformed Britain entirely. It was a startling turn of events, and not by any means a guaranteed outcome--some of the other Germanic peoples of central, eastern, and northern Europe would take another half-millennium to fully convert to the Christian faith. Something swift and striking was afoot in seventh-century England, and it gives me hope for today.We too live in an age where it looks like the former place of Christianity in our society is vanishing before our eyes. Like the earliest British Christians, we've seen tides of unfaith roll into our civilization with all the alarming power and swiftness of an invasion. Not only atheism, but paganism itself is making a startling return, and one gets the sense in visiting some of these old churches that one is really just walking through the ruins of a bygone age. The Christian world has fallen, and a new Dark Ages opens before us. Many readers will feel this sensibility about the course things are taking in America, but it is far more visible in western Europe, where the old churches built to call all the people to worship largely stand empty, save for a handful. Like Britain in the sixth century, it looks like Christianity's time has come and gone, and a pagan and disinterested populace looks everywhere for solace except to the old faith.

Marker in Ely CathedralBut the sixth century was not the end of the story. Let's not forget just how fast the story changed, and how complete was the transformation effected by that change. There is no falling away so far and so completely that God is not mighty enough to bring us back. Even now, I wonder if we're not already seeing the seeds of a significant revival, as more and more public intellectuals begin to voice their doubts about the explanatory power of atheism. Walking around Oxford, the greatest university in the world, it is almost impossible not to bump into the question of God around every corner. It might be the case, just maybe, that the bleakness of European atheism in the twentieth century will fade in the memory as a blip in the storyline, like the pagan resurgence of sixth-century Britain, and that the twenty-first century will one day be remembered for a host of missionary-saints, with new cathedrals shooting up to embrace the sky. Bottom line: it's worth remembering that the West has seen a "post-Christian" age before, back in sixth-century Britain (and it's far from the only one). But it wasn't really post-Christian after all. It turned out, in the most marvelous way, to have been a pre-Christian age, a mere pause in the music before the symphony thundered on.

Marker in Ely CathedralBut the sixth century was not the end of the story. Let's not forget just how fast the story changed, and how complete was the transformation effected by that change. There is no falling away so far and so completely that God is not mighty enough to bring us back. Even now, I wonder if we're not already seeing the seeds of a significant revival, as more and more public intellectuals begin to voice their doubts about the explanatory power of atheism. Walking around Oxford, the greatest university in the world, it is almost impossible not to bump into the question of God around every corner. It might be the case, just maybe, that the bleakness of European atheism in the twentieth century will fade in the memory as a blip in the storyline, like the pagan resurgence of sixth-century Britain, and that the twenty-first century will one day be remembered for a host of missionary-saints, with new cathedrals shooting up to embrace the sky. Bottom line: it's worth remembering that the West has seen a "post-Christian" age before, back in sixth-century Britain (and it's far from the only one). But it wasn't really post-Christian after all. It turned out, in the most marvelous way, to have been a pre-Christian age, a mere pause in the music before the symphony thundered on.

August 17, 2024

A London Day before Heading Home

The final part of my trip was a little stopover in the London area before my flight home to Maine (where I'm now trying to recover from jet lag). As with much of the trip, I wanted to take the opportunity to see a few important church history sites, so I spent the day checking off a few more cathedrals (St Albans, Southwark, and St Paul's) and zipping around the Tube to see churches and memorials associated with some of my post-Reformation heroes.

Stayed at the Highbury Centre, the same place my friends and I had stayed

Stayed at the Highbury Centre, the same place my friends and I had stayedduring a college semester in London some 20+ years ago

At the Isaac Watts memorial in Abney Park

At the Isaac Watts memorial in Abney Park John Wesley's memorial and historic chapel

John Wesley's memorial and historic chapel John Bunyan's memorial in Bunhill Fields

John Bunyan's memorial in Bunhill Fields St. Mary Woolnoth, John Newton's church

St. Mary Woolnoth, John Newton's church The old pub on Fleet Street that G. K. Chesterton frequented

The old pub on Fleet Street that G. K. Chesterton frequented Southwark Cathedral, where Shakespeare was a parishioner

Southwark Cathedral, where Shakespeare was a parishioner The Lancelot Andrewes memorial in Southwark Cathedral

The Lancelot Andrewes memorial in Southwark Cathedral Metropolitan Tabernacle, Charles Spurgeon's old church

Metropolitan Tabernacle, Charles Spurgeon's old church Holy Trinity Church in Clapham, the church that William Wilberforce

Holy Trinity Church in Clapham, the church that William Wilberforceand his friends attended in London

The altar in St. Paul's Cathedral, where (in a previous edifice)

The altar in St. Paul's Cathedral, where (in a previous edifice)John Donne had served as rector

August 12, 2024

Norwich and the Eastern Cathedrals

After my conference in Oxford wrapped up, I took a couple days to head east, into East Anglia and Norfolk, which, like Kent, were early centers of the Anglo-Saxon reception of Christianity in the 7th century. I stopped at cathedrals in Peterborough, Ely, Bury St Edmunds, and Norwich, but the real goal for me was to reach a much smaller church, and one that came a little later in Christian history: St Julian's church, Norwich. This medieval church had been home to one of the great Christian writers of the Middle Ages, an anonymous woman now know only for the church in which she lived as an anchorite (a hermit-like monastic in permanent residence in a cell attached to a church): Julian of Norwich. Her book, Revelations of Divine Love, has long been among the books I've most highly treasured, with words that elucidate the love of God to me. So amid all the cathedrals and their splendor, I spent most of my time in the reconstructed Church of St Julian (there's a guesthouse nearby where I stayed), and was privileged to have church there Sunday morning. Next up, after a bit of birding here in the Norfolk area, it's back to London for a whirlwind look at some of the city's church history sites, and then a flight back home.

Peterborough Cathedral

Peterborough Cathedral  Norwich Cathedral

Norwich Cathedral St Edmundsbury Cathedral

St Edmundsbury Cathedral  Ely Cathedral

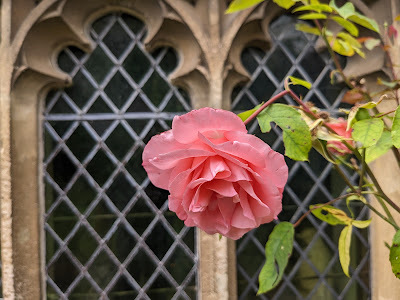

Ely Cathedral  A rose growing outside the Lady Julian's cell

A rose growing outside the Lady Julian's cellAugust 9, 2024

This Week in Oxford, Part 2

Most of the week was spent at the patristics conference in Oxford. I presented my paper on Thursday--"The Advantage of Rusticity: Patrick's Dissent from Patristic Interpretations of Great Commission Texts (Confessio 40)"--and it seemed to be well-received. Here are a few more pictures from around the city. Next, it's off for a few days to see a site associated with one of my favorite medieval writers, Julian of Norwich.

The Radcliffe Camera (part of the Bodleian Library),

The Radcliffe Camera (part of the Bodleian Library),an iconic Oxford landmark

The Examination Schools, where most of the

The Examination Schools, where most of theconference's sessions were held

Paying my respects to C. S. Lewis at his grave

Paying my respects to C. S. Lewis at his gravein Headington Quarry, just outside Oxford

The conference's opening session

The conference's opening session in Christ Church Cathedral

Christ Church College and Cathedral

Christ Church College and Cathedral(where John & Charles Wesley studied and were ordained)

August 8, 2024

This Week in Oxford, Part 1

Magdalene College Chapel

Magdalene College Chapel  On the cloistered quad of Magdalene College

On the cloistered quad of Magdalene College  Pulpit from which Lewis preached his

Pulpit from which Lewis preached his"Weight of Glory Sermon," at University Church

(John Wesley also preached here)

Martyrs Monument, commemorating the executions

Martyrs Monument, commemorating the executionsof great Reformers like Thomas Cranmer

The pub where Lewis & Tolkien used to hang out

The pub where Lewis & Tolkien used to hang out Keble College Chapel

Keble College ChapelAugust 7, 2024

Day 4

On Sunday I finished the pilgrimage trail, walking the last few miles through the woods from Fordwich to Canterbury. I was able to attend both a communion service and the office of morning prayer in Canterbury Cathedral. I also visited the ruins of Augustine's old abbey and St Martin's, the oldest continuously-used church in the English-speaking world, where Christians have been worshipping since c.600 A.D. After that, it was on the train to my conference in Oxford (with just another quick stop along the way at Rochester Cathedral, where another member of Augustine's original mission team also established a church).

A view over St Augustine's Abbey,

A view over St Augustine's Abbey,with Canterbury Cathedral in the distance (left)

The Lady Chapel of Canterbury Cathedral,

The Lady Chapel of Canterbury Cathedral,where we said morning prayer

St Martin's

St Martin's  In a side-chapel of Rochester Cathedral

In a side-chapel of Rochester CathedralAugust 6, 2024

Days 2 & 3

For days 2 and 3 of my journey (Fri/Sat last week), I undertook a walking pilgrimage across Kent, England's southeastern region. Not only was this area the ancestral homeland of the Burden family, it was also the site of a major event in church history, one that was near and dear to my heart as a student of early Christian missions: the evangelization of the Angles & Saxons, setting England on a remarkable history of Christian faith. This happened near the end of the sixth century, when Pope Gregory deployed Augustine (not the more famous church father) and a band of helpers to bring the gospel to the new pagan settlers of Britain. Augustine landed near what is now Ramsgate, on England's southeastern tip, where he met and preached to the king, then was invited to come and establish a mission at the royal city of Canterbury. My journey, then, would be to walk that ancient mission team's journey, from Ramsgate to Canterbury, where the old abbey of St Augustine of Canterbury still lies. Here are the two main days of that journey, ending at Fordwich, just outside Canterbury. Tomorrow I'll post about my entry into Canterbury on Sunday morning.

Ramsgate harbor

Ramsgate harbor Shrine of St Augustine of Canterbury, Ramsgate

Shrine of St Augustine of Canterbury, Ramsgate  St Augustine's Cross, marking where

St Augustine's Cross, marking wherehe preached the gospel to the king

St Mary's Church, Fordwich -

St Mary's Church, Fordwich -a decommissioned medieval church

that now hosts pilgrims -

I stayed one night here

Path through the woods near the River Stour

Path through the woods near the River StourAugust 5, 2024

Catching Up on Day 1 of the Pilgrimage/Conference Adventure

(Sorry it's taken me a bit longer to start posting than I anticipated. The first leg of the adventure was a walking pilgrimage across Kent, so WiFi was understandably hard to come by sometimes. Even here in Oxford it's spotty, so I'll have to post a bit at a time, but I'll try to make it daily.)

Day 1: Stopping in at the village churches of my Burden ancestors!

Borden (likely where the Burdens

Borden (likely where the Burdens lived some 900 years ago)

Interior of the Borden church

Interior of the Borden church (exterior below)

Church of St Peter & St Paul, Borden

Church of St Peter & St Paul, Borden (tower goes back to earliest construction)

Now in Headcorn, where the Burdens lived

Now in Headcorn, where the Burdens lived from about 1300 until emigrating to North America

The Headcorn church, coincidentally

The Headcorn church, coincidentally also named in honor of Peter and Paul

Interior of the Headcorn church

Interior of the Headcorn church That's it for now. I'll upload a photo log of my second day tomorrow. I'm posting from a cell phone rather than a computer, so any longform written reflections, which you might justly have expected of me, will have to wait till my return.