Benjamin M. Weilert's Blog: BMW the Blog, page 9

November 20, 2018

An Engineer’s Guide to NaNoWriMo (or how I grew from a newbie to a veteran)

This post was originally written for the NaNoWriMo blog. You can check it out here (it’s been slightly modified, but the content’s basically the same).

I’m an engineer. While most of my colleagues use this as an excuse to keep themselves from writing anything, I argue it’s the reason they need to be the best writers. The concepts engineers can create in their minds still need to be communicated to the world. Concepts never imagined before. Similarly, how many writers are out there with an idea nobody has ever read, just waiting to get it onto the page? As an engineer, I have a particular set of skills—some would say “quirks”—that have helped me over the last eight years of NaNoWriMo grow from just barely finishing to writing rapidly and voluminously.

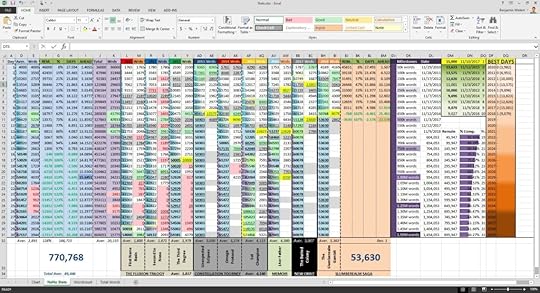

Most engineers are known for their problem-solving skills, and NaNoWriMo presents an interesting problem: how do I write 50,000 words of a novel in 30 days? Like most problems, I resort to spreadsheets— as many engineers do. After all, I’m already writing the book in Microsoft Word, so it’s not hard to set up an Excel spreadsheet to track my progress. This spreadsheet is what helped me grow as a writer. Engineers also like numbered lists, so here’s how tracking my writing helped motivate me to become a better (or at least faster/more efficient) writer:

1,667 words are the MINIMUM – My spreadsheet doesn’t allow me to slack. If the “words written” column for that day is less than 1,667 words, I have to keep writing. I may be 15 days ahead, but until I get those 1,667, I can’t stop writing for that day.

Compete against my past self – What’s nice about a spreadsheet that tracks your NaNoWriMo progress for one year is that it can be used to track your progress for the following years as well. Consequently, I’m always looking at ways to outdo myself each year, whether it’s being further ahead than in previous years, writing more per-day, or writing more than ever before. It’s how I was able to . . .

Finish the 50,000 words of NaNoWriMo in 12 days or less (2013, 2015, 2016, and 2017)

Write over 10,000 words in a single day (2012, 2013, 2015, 2016, and 2017 (x2))

Write 123,456 words in a month (2015)

Recognize trends – As I began to track my NaNoWriMo projects against each other, I started to see trends. I saw that I would usually write a lot during the Veteran’s Day weekend (since I get Veteran’s Day off). I also saw that I would get almost no writing done around Thanksgiving (since I travel out of town for it). Recognizing which days and situations were conducive to my writing helped me to schedule them out in advance so I’d be sure to use them to their utmost capability.

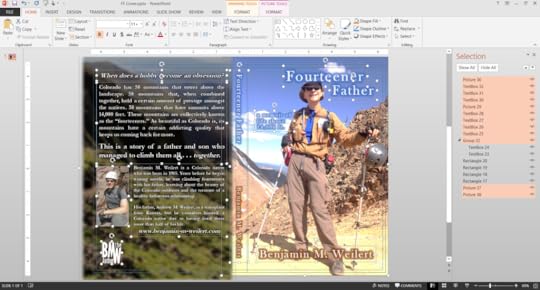

The spreadsheet in all its glory.

The spreadsheet in all its glory.In the end, my spreadsheet allowed me to recognize the small—sometimes hidden—milestones that can give me a push to keep writing. Whether it’s realizing how close I am to 500,000 cumulative words (obtained on November 3rd, 2017), or seeing that I can beat a previous “high score” day from a past NaNoWriMo, these milestones are what made me realize that the impossible feats of veteran writers are actually quite achievable if you break them down into smaller chunks. And what engineer wouldn’t tackle a problem by first breaking it down into manageable pieces? But don’t take this engineer’s word for it, try it for yourself!

October 8, 2018

Why you should schedule your writing

“If you fail to plan, you are planning to fail.”

When it comes to writing, many will consider this alleged quote by Benjamin Franklin to mean that they should outline every single scene of their book, write FBI-level character bios, and practically have every part of the book already written in their head before they sit down and actually put it to the page. While this can sound like a daunting task, it misses the point of the quote. It’s not that writers should plan out their books, it’s that they should plan out their time.

Time management is more important than you think.

Back when I was becoming more serious about writing, I had all the time in the world. My job was stable, and I had a good work/life balance that allowed me to come home and do all the writing or editing I would need to complete the projects that I had started. Plus, at the time, I was single and had very few social obligations (as many introverts usually do). Consequently, I was able to write, edit, and publish a book in about nine months. Granted, they weren’t perfect books, but at least I actually had something physical by the end of the day that I could hold and say, “I made this!”

This all changed when I found myself in a relationship which eventually led to my marriage. Suddenly, I had someone else that occupied a lot of my time. Plus, as I began to advance in my career, I would more frequently have evenings that I didn’t want to do anything more than relax on the couch to compensate for the stress I had endured during the day. While my writing speed had increased in this time—I was finishing first drafts in only a few weeks—the time I needed to edit and polish had vanished.

It’s not necessarily that the time itself vanished, but more that the priorities of my life changed so much that I hadn’t accounted for the time to write or edit my writing projects. After things settled down to a steady state, I took a hard look at my schedule and realized that I wasn’t going to get anything done if I didn’t plan for it. I needed to schedule my writing.

Priorities determine the time you spend.

I know that most writers want to love the writing process. They want to be struck by inspiration and merely head over to a comfy chair with a hot cup of tea or coffee and let the muse flow through their fingers into their laptop screens. I believe this is a fantasy. Nothing will ever be written if this is what a writer is waiting for. Instead, I think writers should approach the act of writing as “work.” I know this ties the connotations of drudgery to the creative process, but there’s a reason it needs to be seen as a task to complete and not a chance encounter with the creative gods.

Think of it this way: if you work at a regular 9-to-5 job at a desk in front of a computer, you’re usually required to keep a certain “schedule” in order to complete your assigned tasks. Well, if you want to achieve your self-assigned writing tasks, you need to keep a schedule as well. Now, it doesn’t need to be 40 hours a week of writing. Maybe just an evening once a week (mine is Thursdays). Maybe set your alarm to wake you up and do an hour of writing every day before you would usually get up. The crux of the matter is that you have to decide if writing is important enough to block out the time to do it.

Another way to think of it like a “date night.” Anyone who is married knows that scheduling date nights with your significant other is important in order to escape the stresses of the home life and keep the romance and communication alive in the relationship. While you’ll likely want to coordinate your “writing dates” with your spouse, you also need to hold them at the highest priority. Your marriage will likely suffer if other circumstances (within reason) cancel date nights, just like your writing might suffer if you let anything that comes along interrupt or cancel your “writing dates.” You still might want to be flexible and move your writing dates to a different day in the week if needed, but don’t let too many opportunities overthrow your scheduled writing time. If this isn’t feasible, then perhaps you need to think about consolidating your writing into one big chunk of time.

If you can’t schedule all the time, perhaps schedule in a chunk.

With National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) just around the corner, it might be a chance to get all your writing done at once. Since NaNoWriMo is the concrete goal of writing 50,000 words of the first draft of a novel by the concrete deadline of the end of November, there’s an impetus for writers everywhere to forego some of the regular activities in their lives and commit their evenings and weekends to writing. I generally set aside the time after dinner and before going to bed during the weekdays in November in order to get my daily words written. Weekends are when I sit down and really get my writing done, often going for stretches of eight hours and putting in upwards of 10,000 words toward the 50,000-word goal in single sittings. My wife knows that this is my time to write, and I will often have an excuse not to attend events that I usually go to on a regular basis (I still go to work, obviously). The key to success is definitely to plan when you’re going to write and to write at that time every day.

In the end, time is a resource for a writer. Those writers who control their time well can find themselves to be incredibly productive. Others who let time control them and fail to plan their writing time will often find themselves with half-finished manuscripts and guilt for never finishing the book that they’ve always wanted to write. Which kind of writer do you want to be? Where can you schedule writing in your hectic life to make sure that you dedicate time to it?

September 18, 2018

The ABC+ of Beta Reading

A few months ago, I discussed how there are four essential edits that every author should perform on their manuscript. While the author can do half of these edits by themselves, two edits need the input of other people: editors and beta readers. Authors shouldn’t expect editors to ask what to look for during their review, but most beta readers might not know the types of useful feedback the author is seeking with their review. It doesn’t hurt to provide beta readers with a little guidance on what to be looking for when they read the author’s manuscript.

The benefits of beta readers are due to the fact that they aren’t necessarily professionals reading your work. They won’t have the background to tell you if you’re using too many dangling participles (like your editor should). Instead, they have the “layman” view of someone who would pick up your book and read it for entertainment purposes. Consequently, the beta readers should be able to identify three of the big problems that a manuscript can have that might make future readers fail to finish the book. They can also identify the parts of the manuscript that work and that you’d want to keep during subsequent edits. I like to call these the “ABC+” of beta reading:

Annoying/Awkward:

For many readers, a book changes from being entertaining to being irritating when the characters or plot become annoying. Perhaps it’s a verbal tic in one of the characters’ dialogue. Maybe it’s a plotline that doesn’t advance anything. Similarly, there are occasional bits of prose that might pull a reader out of the immersive reality of the book because it’s written awkwardly. There might be a phrase or conversation can make sense in an author’s head and when they read it on the page, but when someone else with a fresh perspective reads it, they should identify if it’s not working for them. Beta readers should be searching for these rough spots so the author knows what to polish in future iterations.

Annoying/Awkward:

For many readers, a book changes from being entertaining to being irritating when the characters or plot become annoying. Perhaps it’s a verbal tic in one of the characters’ dialogue. Maybe it’s a plotline that doesn’t advance anything. Similarly, there are occasional bits of prose that might pull a reader out of the immersive reality of the book because it’s written awkwardly. There might be a phrase or conversation can make sense in an author’s head and when they read it on the page, but when someone else with a fresh perspective reads it, they should identify if it’s not working for them. Beta readers should be searching for these rough spots so the author knows what to polish in future iterations.Boring: If it becomes “work” to read through a book, it’s likely due to the plot becoming boring. If you spend too much time in exposition, you might lose your readers due to boredom. Even if you have a fantastic, action-packed ending that you think is great, nobody would know it if they put your book down too early and never picked it up again. If you’re lucky enough to have dedicated beta readers, they can sometimes push through these boring parts and let you know where you need to “trim the fat” to make your manuscript a tighter and better-flowing work.

Confusing: When an author creates a world on the page, a lot can depend on how easy it is for a reader to understand that world. In the genres of fantasy and science fiction, there can be a lot of unique and creative ideas presented through the author’s writing. However, if this new world doesn’t make sense, you might lose your readers. Similarly, if the characters in your book don’t act consistently—even when taking into account the growth gained in a character arc—then some readers will likely find this illogical change confusing (and perhaps even annoying). As with the previous two elements of beta reading, sometimes the author can be too close to their writing to notice these flaws. The astute beta reader will identify these areas that are confusing and let the author know that a little more explanation might be in order.

+ The Positive: Most authors will have scenes that they loved to write. Perhaps it’s the eventual romance between the two main characters. Maybe it’s the climactic action sequence. Whatever it is, if the beta readers also like these moments, it helps to let the author know that they were on-target with their writing. Any little bit of encouragement helps the author through the drudgery of editing. From mentioning how a particular line of dialogue made them laugh to how a succinct description was spot-on, beta readers are often the first people to tell the author how great their work will be.

Now, other authors might have different criteria for their beta readers, and sometimes there’s a specific spot that they’ll want some particular focus on, but I think these four elements can help beta readers be effective in providing feedback on an author’s manuscript. After all, with something to search for, the beta readers will pay much closer attention to the book itself and perhaps notice something that needs to be polished that they wouldn’t have normally seen if reading it with no guidance.

August 7, 2018

3 unexpected programs to help you publish a book [PART 3/3]

Over the last few months, I’ve hopefully opened your eyes to some of the neat tricks you can use to help publish your book using the Microsoft Office suite. Microsoft Word is an obvious choice for writing, and Microsoft Excel can also be useful to manage lists and other planning information, but did you know there’s one more program that can help you publish your book as well?

Up until now, the programs I’ve suggested are ones that you’d likely use anyway if you were trying to organize your work or polish your manuscript. The key was merely using the lesser-known tools within these programs to make your life as a writer easier. This month, I’d like to suggest something that might shock you and will require you to use a program in a slightly different manner than it’s usually used. That program is:

MICROSOFT POWERPOINT

Most people associate PowerPoint with corporations, presentations, and goofy animations. While these are the typical uses for the program, it wasn’t until recently that I realized I could use PowerPoint as part of my publishing process. Some programs like Scrivener and Adobe Photoshop might have some useful tools as part of their suite of functions that can help authors with their projects, but these programs are a bit more expensive and less universally available than Microsoft PowerPoint. By this point, you might be asking, “How do I use PowerPoint to publish a book?” Well, there are three ways it can help . . .

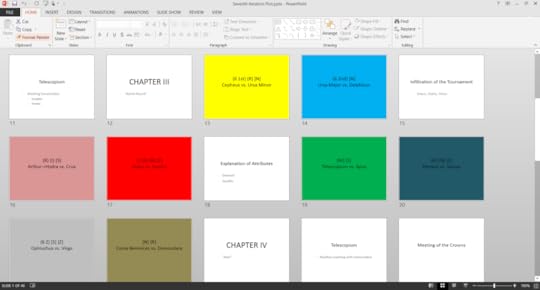

Scene organization: How often have you seen a poster board full of index cards or post-it notes where an author is planning out what happens in their story? Each of the critical scenes in a book can potentially be re-arranged, especially if there are multiple sub-plots involving different characters. If you color the backgrounds of some of your PowerPoint slides and use the “Slide Sorter” option at the bottom of the window, you can easily see at a glance where all your scenes are in relation to each other. With big enough fonts, you can also read these “index cards” so you know what the main thrust of each scene is. While Scrivener has a much more advanced “index card” system, PowerPoint can sufficiently provide a way to organize the scenes in your book so that you can plan out the flow of the plot before you even start writing.

Social media: In this digital age, social media is an essential facet of an author’s duties. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, Tumbler, and more are required to gain a social media following. However, each of these platforms has slightly different image requirements. Cover photos for Facebook and profile banners for Twitter are slightly different sizes. Pinterest favors long vertical posts. Instagram is designed for square pictures. Fortunately, PowerPoint can adjust the slide size to fit whatever you need. Just go to the “Design” tab and click the “Customize” drop-down. From there, choose “Slide Size” and “Custom Slide Size…” From the pop-up box, you can adjust the width and height of your slide to meet your needs. You can even go to the “View” tab, select “Slide Master” in the “Master Views” section, and add your logo or watermark to every slide that you create. Then, all you have to do is fill each slide with the social media content you want, and you’ll be ensured that it’ll be the right size for the platform. One key thing I forgot to mention in here is the crux of the whole PowerPoint benefit—you can save PowerPoint slides as image files. That’s right! JPEGs and PNGs are just a few of the many formats PowerPoint files can be saved as.

Cover: Most people will use Adobe Photoshop to create the covers for their books, but PowerPoint uses the same “layers” concept that Photoshop does. I have an elementary knowledge of how to use Photoshop, but I find the addition of (and arrangement of) text boxes, shapes, and pictures is a lot easier in PowerPoint. Under the “Home” tab, the “Drawing” section allows you to draw boxes that can identify the trim and safe limits of your cover, align text so it remains centered on the cover, and group together whole sections of objects so they can easily be moved or copied elsewhere. You can even use some of PowerPoint’s “effects” on shapes, pictures, and text. Effects like shadow, reflection, glow, soft edges, bevel and 3-D Rotation can add just a little more pop to the cover. Under the “Arrange” drop-down, you can even select “Selection Pane” to see all the objects you have in the PowerPoint slide—hiding and moving them toward the front or back of the slide in one easy panel. Because you can adjust the slide size in PowerPoint (like I mentioned above), you can modify the slide size to be the exact size of your cover! One thing you’ll have to make sure you do before you save your cover, though, is change the resolution of the exported images. Printable images must be at least 300 dots per square inch (dpi), but PowerPoint’s default is much lower than this. To increase the dpi for exported images, you’ll have to make a simple change in your computer’s registry (instructions for how to do this are located on Microsoft’s support site). There are still limitations to this 300dpi change, so you’ll have to play with the size of your PowerPoint slides to ensure they’re still being exported at the highest resolution.

At this point, you should have a loose understanding of a few options and tools available through the three most-common Microsoft Office programs that can help you with your book-publishing goals. Sure, there are still limitations to these programs—they’re not as powerful or expensive as the ones tailored for writing—but there are also plenty of hidden gems that you can only find if you play around with them a little bit. I’ve discovered most of these tips and tricks over the years by wondering “what if,” then seeing if I could create it in Microsoft Word, Excel, or PowerPoint.

Necessity is the mother of invention, and if you don’t have enough money for the expensive programs, why not see if the Microsoft Office suite can meet your needs?

DISCLAIMER: Throughout this three-part post about Microsoft Office, I have been touting the benefits of these programs. I have not been paid by Microsoft to endorse their programs; I merely feel—through my own experiences—that they’re the most easily accessible programs that writers often ignore in favor of more expensive ones.

July 3, 2018

3 unexpected programs to help you publish a book [PART 2/3]

Last month, I told you how the Microsoft Office suite can help you with your writing. I covered Microsoft Word, and how it’s more powerful than just a standard word processor. By getting to know some of the more obscure features of these (usually) easily obtainable and available programs, writers can take control of their writing without having to purchase expensive computer programs.

With Microsoft Word, I covered how Section Breaks, Styles, and Formatting can help a writer create a professional-looking book with less effort. Even though our next program isn’t used directly for the actual writing of a book, it is incredibly valuable for planning and prepping. It can also be used during the polishing phase of a manuscript as well. I refer, of course, to:

MICROSOFT EXCEL

As an engineer, I love to use spreadsheets, and Excel is the king of the spreadsheet programs. Any time I need to write a list or do some calculations, I open up a new Excel spreadsheet and get to work. Just like Microsoft Word, Excel has plenty of capability most people never use. The following three tools in Microsoft Excel are only a few of the numerous features of this powerful program . . .

Filter: In the lead-up to writing a book, I usually have plenty of lists to help me organize my thoughts. While Microsoft Word can work for simple bullet lists, there are often cases where the complexity of the data is more extensive than just a series of names, places, or plot points. Take my 2013 NaNoWriMo project, which was the first book in The Constellation Tournament trilogy. I had 88 distinct characters in this series, and each one had slightly different attributes that I needed to be able to group based on a variety of factors. By using the “Filter” function under the “Data” tab, I was able to sort these characters based on gender, size, and abilities. Being able to filter my huge list of characters made it easy for me to recall each of their attributes as part of a larger group. When it was time to write the book, I could simply and easily bring up the information I needed because I could sort based on these different attributes. To use the Filter function (which is also available on the “Home” tab under the “Editing” section), just select the top row of your spreadsheet (where your labeled categories should be), and click the little funnel icon that says “Filter.” This gives the top row a series of drop-down menus that you can use to sort, filter, and organize your data any way you want.

Data Grouping: Under the same “Data” tab where you’ll find the “Filter” function, there’s a section called “Outline.” For any writer who has planned out their work, an outline is an essential function of that preparation. Again, you could use Microsoft Word and create a bullet list that highlights the critical plot points, or you could put the same list of plot points in Excel and be able to expand and collapse whole chapters at will. By using Data Grouping, you can essentially put as much or as little detail into your outline as you want, while efficiently controlling what level of detail you want to see. What’s nice about this is how you can create timelines for your plot and perceive at a glance when specific events happen in the story. Because Excel is still a computational tool, you can use the formulas inherent within it to calculate the timeline of your book. For example, let’s say a particular event takes a week to occur, but there are a series of smaller tasks that lead up to this event. If you put in the amount of time each of the smaller tasks will take for each section of the plot, then add them together at the main bullets, you can then see how much time passes for the larger parts of the book by collapsing the plot points that you’ve created using Data Grouping. In this way, you can see gaps in your timeline. Similarly, if you’re listing out dates and times that events occur for parallel storylines, you can use the Filter function to sort them chronologically before dividing them into your sections and chapters via Data Grouping. There’s plenty of potential applications for this feature if you spend some time and learn how to use it.

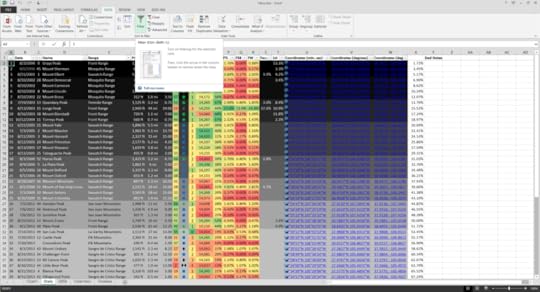

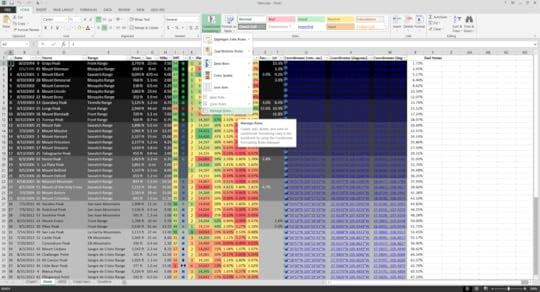

Conditional Formatting: A huge table of data can be intimidating to digest at a glance. Sometimes we get lost in the numbers and values of the spreadsheet and don’t know what to look for. Conditional Formatting helps to curb this problem by applying visual cues to a spreadsheet. Underneath the “Styles” section of the “Home” tab, there’s a drop-down for Conditional Formatting that gives you some options. Do you want to know which of your characters are the tallest or shortest? Apply a Top/Bottom Rule to the column that contains the characters’ heights. Does a key event happen at a particular time in the story? Highlight anything that occurs before it as “Green” and anything that happens after as “Red” to remind yourself what the mood of the characters should be. Is there a particular attribute that you want to be sorted in a specific way? Add a Color Scale to show the difference between the values when the table is sorted in different ways. Basically, Conditional Formatting helps to automatically add color to your spreadsheet, thus making it easier for you to read and find the information you need.

While these three tools are quite powerful, the capabilities of Microsoft Excel extend well beyond them. I haven’t even covered Charts, Formulas, or Text to Columns, each of which can help a writer plan out their work, as well as help them ensure they can identify their plot holes before they write them into the story. Just be careful to not spend so much time in the planning phase going down Excel’s numerous rabbit holes. You’ll still have to open up Microsoft Word to write the story after all.

Next month, we’ll discuss how Microsoft PowerPoint is a cheap alternative to Photoshop and how it can help you organize the scenes of your plot.

June 5, 2018

3 unexpected programs to help you publish a book [PART 1/3]

Many months ago, I described the amount of work a writer would need to do by themselves to publish a book. Not only is there research, formatting, and graphic design involved, the writer also has to write said book. This whole process can be daunting, especially in the digital age. We have so many different programs at our fingertips to help us plan, write, and publish. A lot of these programs can cost a significant amount of money. Sure, programs like Aeon Timeline, Evernote, and Scrivener might be worth the money in the long run, but you’ll inevitably have to learn how to use these programs, which can eat into your writing time.

What if I were to tell you that there’s a suite of programs you probably already have installed on your computer that can accomplish many of the same functions as the programs that cost a lot more? Many of you probably already use these programs on a regular basis, so there are only a few minor tweaks you’d need to make to use their full power. Even if you don’t own these programs, you might be able to get them for cheap via your work or school. There are even trial versions you can download for 30 days if you’re working under a time crunch.

By now, you’re probably asking, “What are these glorious programs?” Two words: Microsoft Office. The most-used triad of this commonly-available set of programs are Microsoft Word, Microsoft Excel, and Microsoft PowerPoint. With these three programs, you can plan, write, and publish your book in a way that’s still as professional as the authors who publish traditionally. Granted, you’ll have to put in some work to ensure your book looks just as good as the ones released by major publishers, but these three programs make it doable.

Let’s go over some of the tips and tricks for how to use these programs to their utmost capability:

MICROSOFT WORD

When you opened this blog post, you probably didn’t expect to see Microsoft Word as an “unexpected program” for publishing your book. While you can do outlines and other research/planning/writing in any word processor, the real power of Microsoft Word comes during the polishing stages of your book. I will also mention that the .doc and .docx formats are commonly accepted by such self-publishing resources as CreateSpace and Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP), making it almost a requirement to own a copy of Word if you want to self-publish.

There are numerous tools at your disposal in Microsoft Word, but the following three are perhaps the most useful . . .

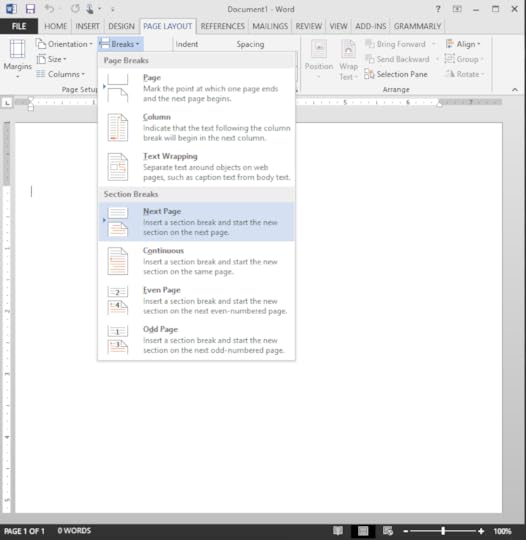

Section Breaks: Have you ever wondered how some authors are able to put the chapter title in the header? The simple answer is “Section Breaks.” This tool is under the “Layout” tab and found in the “Page Setup” section under “Breaks.” When you reach the end of a chapter, add a “Next Page” section break to let your Word document know you’ve moved on to the next chapter. You can then go into the headers and footers and tell them to match the previous section or to be unique to the new section. Most books will have the headers of one of the pages contain the author’s name, while the other header can display the title of the book. These require matching to the previous section, but you can break the synchronization to make each section/chapter easier to find when flipping through your book. Just make sure to check each section before publishing to ensure the formatting for each of the sections does what you want it to.

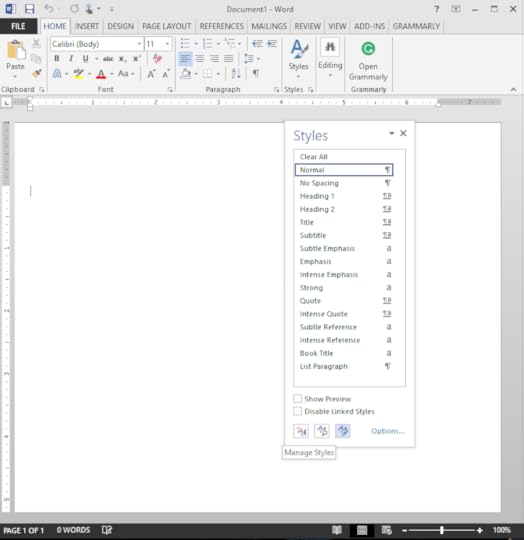

Styles: Let’s say you want to have the main body of your writing as 12-point Garamond with 1.0 line spacing, indented on the first line and in the justify-align format, but you want the first paragraph of a chapter to be the same as the body text, but without the first-line indent. Well, you’re in luck, because you can set up “Styles” to automatically make these changes for you when you apply them to your paragraphs. Underneath the “Home” tab, there’s a section for “Styles” that is criminally underused. If you have a particular set of formatting that you want to repeat over and over again (like chapter headings or paragraph settings), then all you need to do is save these formats as styles and apply as needed. Clicking on the arrow on the bottom right of the Styles section will open up the different options for styles, along with the ability to create new styles and modify existing ones. You can be creative with this, even to the point of creating a style for a particular character’s dialogue, which you can then easily apply each time it occurs in the book. Basically, “Styles” are paintbrushes for how you want your text to appear.

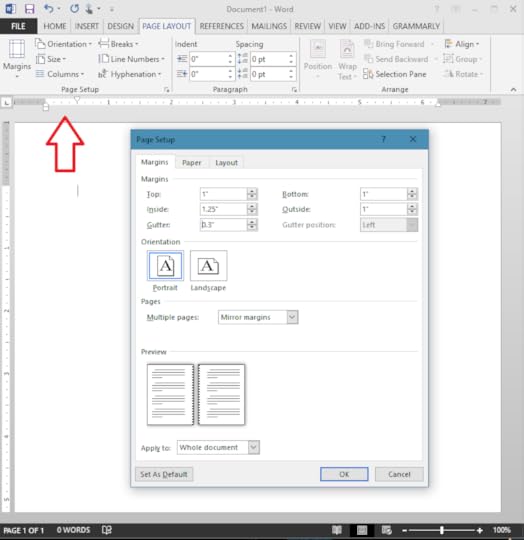

Formatting: While Section Breaks and Styles can—and should—fit underneath this category, it’s one I find can often be neglected when self-publishing a book. Formatting is the one thing that sticks out in a published work, especially if it’s done incorrectly. If you’re unsure of how you want your book to look, pick out one of your favorite, famous authors and see how the interior text is formatted and try to imitate it. Common errors I’ve found are not indenting first lines of paragraphs, keeping paragraphs in right-align format instead of justify-align, and having text too close to the gutter (the area where the pages come together). Word has settings to fix all of these things. From the ruler at the top of the page to the “Margins” section of Page Setup, these types of formatting are usually pretty easy to find and manipulate. Basically, if you’re using the “default” settings of Word, people will notice. Take a little time to familiarize yourself with the formatting options of Word or—at the very least—download a template from CreateSpace to have a starting point.

There are plenty more capabilities present in Microsoft Word, but I think these three help the most in efficiently polishing a manuscript into something that looks professional. Just make sure you save a copy of your work before you start making any changes that are too drastic. After all, Word is a powerful program, but it can often reach its limits (or your limits of controlling it).

Next month, we’ll go over how to use Microsoft Excel to aid your planning and research.

May 8, 2018

Why “spell check” is not enough

English is hard. Certain words may be spelled the same but have completely different meanings. Other words may sound the same, but have different spellings (and thus, different meanings). There are even words that may change meaning with the addition or subtraction of a single letter. This is why context is a huge part of the English language. Depending on the words around it, the correct word can be implied, but an incorrect word will still jar the reader enough to pull them from the story. They’ll likely re-read the sentence, trying to make sure they understood the author correctly. When they realize the writer made a mistake, they’ll continue reading, but they’ll have a seed of mistrust planted in their minds. From that point onward, they’ll question every word the writer uses, just to make sure they aren’t mistaken again. This increases scrutiny on the part of the reader, and can often distract from the author’s intent: conveying a story.

By now, we’re all aware of the common homophones/homographs that will trip up the inexperienced writer. Here’s a brief list:

their/there/they’re

too/two/to

your/you’re

we’re/were

its/it’s

than/then

While the experienced writer will know which of these homophones to use, I’ve noticed many mistakes will sneak through. These are words that won’t be caught by spell check because they’re still spelled correctly, just without the correct context. Sometimes these errors can be due to the writer hearing the word in question, but not knowing its correct spelling. The best way to improve your writing and avoid these mistakes is to read . . . a lot. In the end, vocabulary errors are the result of knowing a word, but not knowing the correct way to use it. By reading as much as you can, you’ll eventually pick up the correct context for words like “affect” (to act upon) when compared to the similar “effect” (the result of). Below is a list of words, in no particular order, that would be missed by spell check (they can even be missed by the most astute readers as well):

Blond/Blonde – Much like fiancé and fiancée, the extra “e” is meant to indicate the gender of the word. “Blond” is a color associated with men, whereas “Blonde” is the female equivalent. This also applies to protégé/ protégée, which themselves are different from the word “prodigy” (a young person with exceptional talent).

Raze/Raise – If you raze a family, you’ll likely go to jail for murder. “Raze” is associated with demolition, whereas “Raise” is lifting something up. These two words are on entirely different ends of the spectrum.

Elicit/Illicit – If you want to “elicit” (to bring out) a response from someone, make sure you don’t use “illicit” (illegal) substances.

Insure/Ensure – These two are similar but are different enough to bear mentioning. If you “ensure” something, you guarantee it will happen, whereas if you “insure” something, you are protecting it from future harm.

Shown/Shone – “Shown” and “shone” both sound the same, but “show” and “shine” do not. Both are past participle verbs, but “shown” is the past form of “show” and “shone” is the past form of “shine.”

Peak/Peek/Pique – One of the worst review requests I have received wanted to know if the synopsis of a book “peaked my interest.” Misuse of these three words is more common than you’d think (the first two being the worst offenders). Just so we’re clear, “peak” is the top of something, “peek” is a quick glance at something, and “pique” is curiosity about something.

Taught/Taut – I’ve been guilty of this one. “Taught” is when a student learns something. “Taut” is a condition of tightness (like a rope or piece of fabric).

Rapt/Wrapped – These words might sound the same, but they have very different meanings. “Rapt” is an adjective (engrossed or absorbed), whereas “wrapped” is a verb (to cover something). Writers who struggle with spelling should be extremely careful that they don’t accidentally use the word “raped” either, as it can ruin a proper sentence.

Mike/Mic – While “mike” is often an accepted spelling, “mic” is the shortened form of “microphone.” Knowing the original word helps to inform the shortened spelling.

Cubical/Cubicle – Both of these words describe square volumes, but “cubical” is an adjective for a cube-like space, and “cubicle” is the noun used to represent this space.

Accept/Except – Another somewhat common error, “accept” is a verb of inclusion, whereas “except” is a preposition or conjunction dealing with exclusion.

Consul/Console – Two very different words here, as “consul” is a government official and “console” is either a computer system or what you do when dealing with a grieving friend.

Passed/Past – These simple words are often used in place of each other, even if they don’t mean the same thing. “Passed” is used when successfully completing a test or after two objects have completed the act of passing by each other. “Past” refers to everything that has happened up until now.

Please/Pleas – The first of these words is used when you’re asking nicely for something. The second is when you’re begging for it.

Arranged/Arraigned – When an activity like a wedding is “arranged,” plans are made. When someone is “arraigned,” they’re being brought before the court because they’re accused of something.

Conscience/Conscious – A “conscience” is something you have that tells the difference between right and wrong. “Conscious” is what you are when you’re awake.

Shoulder/Soldier – Huge differences here, as one is a joint at the top of your arm, and the other is a fighter in the military.

College/Collage/Colleague – These three words have similar sounds and spellings, but are very different from each other in meaning. “College” is a school of higher learning. “Collage” is a collection of assorted items. “Colleague” is a co-worker or associate.

Lightning/Lightening – The first word is an electrical strike, the second word is the action of lessening a heavy load.

Preceding/Proceeding – If something is “preceding,” it is happening before something else. If something is “proceeding,” it is moving forward or going according to plan.

Exiting/Exciting – When you leave a building, you are “exiting.” If something is stimulating, it is “exciting.”

Breathe/Breath – While both words are linked to similar actions, “breathe” is the verb, and “breath” is the noun that is verbed.

Quiet/Quite/Quit – “Quiet” is without noise. “Quite” is to the greatest extent. “Quit” is to stop.

Fir/Fur/Fire – Another set of words that will sneak by a spell checker, “fir” is an evergreen tree, “fur” is the coat of an animal, and “fire” is a collection of flames.

After reading through the above list, you might be surprised that anyone could confuse some of these words. And yet, I have read many books that have made these errors. Each of the above sets of words came from someone making a mistake and allowing that error to appear in a printed book. This is why quality control is essential, and why you can’t just trust spell check to correct your mistakes. Words have meaning, so make sure you’re using the right ones!

What “spell check” mistakes have you found in published books?

April 10, 2018

The 4 types of edits, and why you need to do them all.

It is a rare feat to be able to write a perfect story. It’s even rarer to do so with the first draft. Hubris blinds the writer who considers the first draft of their writing to be perfect. Some writers might fall into the trap of crafting every single word of their first draft, thereby almost ensuring that the first draft will never be complete. On the other end of the spectrum from the “perfect first draft,” we have writers who will continue to polish a story forever, never settling for “good enough.” While no story can be “perfect,” editing will help to get it close enough for publication. In my experience, editing takes up the majority of the writing process, and for good reason.

While some authors may continually iterate the editing process, I have found that there are four types of edits every writer should use when revising their work. These four types range from simple spot checks to thorough reworking. Each has a purpose, and each will have some amount of overlap so that errors missed in one editing pass will likely be caught during later iterations. Without further ado, let’s explore the four types of edits and why writers should do all four of them.

1. Re-write

Let’s say you’ve just written the first draft of a novel. The first thing you should do, before any one of these revisions is to let it sit for a couple of weeks. If you can spare a month to allow your mind forget the details, that’s great! When you come back to do your revisions, I would suggest opening up the original manuscript and placing a blank document right next to it. In this empty document, you will re-type the entirety of your manuscript. This may sound extreme, but there’s a reason why this type of edit is a useful part of a writer’s toolbox.

Maybe you’ve spent years getting your manuscript written. During that time, some of the details of the first part of your story might not coalesce with the details of the ending. Since you’ve already “read” your story once in the process of writing it, you know what’s going to happen. You know the plot twists, and you know what eventually leads the reader from the first chapter to the inevitable final words of “the end.” While re-writing the entire manuscript may take the most time of any of these editing techniques, it allows the writer the most flexibility to change the story. If there are known plot holes or inconsistencies, it’s easier to fix them as the writer puts them back on a fresh page.

Some might consider a “continuity edit” to be a separate revision, but I would argue that the best way to fix continuity errors is to re-write the whole manuscript. After all, the ending is usually the most recent memory in the author’s mind, so by re-writing the story from the beginning, they’ll have a better idea of how to get there in a consistent manner. Plus, with the daunting task of re-typing everything, the writer will often be able to identify the redundant and repetitive sections and choose to leave them out during this revision. This is also a good chance to cut out any “fluff” that doesn’t add to the story. It might seem extreme, but the re-write is a useful tool that accomplishes some brute-force and big-picture changes to a manuscript that usually cannot be achieved in more detailed edits.

2. Beta Reader Feedback

One of the most useful revisions a writer can make is incorporating feedback from beta readers. When someone else has the chance to read a story, they’ll find the blind spots in the author’s writing. Whether it’s repetitive word usage or clunky exposition, these beta readers are essentially a writer’s first interaction with their audience. If something is annoying to the beta readers, it’ll likely be irritating to the general public. This edit is vital for any author who wants to sell their book, as it ensures the ideas presented in the manuscript are accurately communicated to the reader. I usually tell my beta readers to focus on the A, B, C’s: Is it annoying/awkward? Is it boring? Is it confusing? Don’t forget to remind your beta readers to let you know what works and what they enjoy, as those little gems in your story can encourage you to keep polishing it into a better version of itself.

Depending on how stable the story is to begin with, beta reader feedback might need to come before the full re-write of the story. If some aspects of the plot require significant revisions because they don’t make sense to the reader, it can be easier to start from scratch and rework the manuscript from the beginning. However, if the story only needs a few spots of polishing to explain misunderstood ideas and concepts, then a beta reader revision can be a simple act of addition and subtraction to reach the right balance. If the writer already knows what glaring problems exist in the manuscript, they should fix them before sending it to beta readers. After all, the beta readers should find the problems the writer wouldn’t notice, not the ones the writer already knows need to be fixed.

Not only do beta readers answer the question, “Does it make sense?” but they will usually find a lot of proofreading errors as well. Even if you tell the beta readers that you’ll do proofreading later, they’ll still find these errors and tell you about them. Just like the “continuity edit” can be included in the re-write revision, the “proofreading edit” can be included in the beta reader feedback. Heck, you might even tell your beta readers to point out all the spots they noticed typos or errors so you don’t have to spend nearly as much time tracking down the minor faults that your brain might gloss over. When it comes right down to it, an author’s mind will subconsciously ignore these errors. This is why having other people read the manuscript is vital: they’ll fill in the gaps a writer’s mind won’t recognize.

3. Out-loud

While it might not take as long as a full re-write, reading the manuscript out loud is a vital editing technique. This revision should take place later on in the process, as it won’t necessarily identify any glaring plot holes or areas that need considerable work. What the out-loud revision does is answer the question, “Does it sound right?” There’s a particular cadence and rhythm to an author’s writing that might not be obvious on the page but becomes clear when our ears hear it out loud. Common problems identified in the out-loud revision are repetitive words, awkward wording, and run-on/rambling sentences.

The out-loud revision is essential for anyone looking to have their book made into an audiobook, as these errors in writing style become apparent when spoken out loud. Even for those writers who want their words to remain on the page, an out-loud revision helps make the manuscript “readable.” Often, as a writer puts their thoughts down on paper, the ideas and structure of the sentences make sense at the time. However, when it comes time to read these sentences, it soon becomes apparent that the transfer from the brain to the page became muddled along the way. A writer might not be able to identify the specific problem with a sentence that “sounds wrong,” but at least they’ll know it needs revision.

Despite the fact that an out-loud read-through covers every word in the manuscript, it often takes less time than a full re-write. I have found it to be useful to record the out-loud revision, whether as a podcast or a live video. If you’re recording it, then there’s less temptation to be distracted after finishing each chapter. After all, you don’t want anyone else who comes across the recording to lose interest at the points where the author became distracted and started surfing the internet. Plus, if you’ve recorded yourself reading your writing, then you can go back and listen to it and identify any other areas that might sound incorrect. The one key to keeping the momentum of an out-loud revision is to highlight the portions that need work and make the changes after the reading is complete.

4. Professional Editor

So far, the author can complete all the previous revisions. Sure, the author still needs other people to look over the manuscript during the beta reader phase, but the corrections that result from this feedback are usually “big picture” and might not fix the underlying structure that could be faulty. Essentially, the author can accomplish each of the previous revision types. Because of this, the author does not need to expend any resources other than their time in order to accomplish these edits. For some, these three revisions are enough for them to consider the work “complete” and ready for publication. However, there is a big difference between these manuscripts and the ones who have been revised by a professional editor.

For the self-published author, money is often a limiting factor. A professional editor working at industry rates might cost upward of $1,000 for a manuscript of 100,000 words or more. The tricky part of committing this amount of money is ensuring the results will be worth it. It can be incredibly discouraging to have paid this much money for a book that doesn’t sell. Despite this hefty price tag, there is a significantly noticeable difference between the books that have been author-edited and the ones that have had the touch of a professional editor. Granted, people make mistakes, and some professional editors are not worth the money you paid them. This is why most editors will do a few thousand words for free, so the writer gets an idea of how good they are.

I would consider the professional editor to be the last phase of the writing process. Up until this point, the author has caught and fixed many of the smaller and more distracting errors in their manuscript. The professional editor will help identify and correct the broader problems with the story. If the professional editor is brought in too early, they might end up spending most of their time fixing small errors that could have been caught earlier in the process. If they’re continually finding these minor problems, they might not be able to see the underlying issues in the story itself. In the end, it is still up to the author to be well versed enough in editing and revising to know if an editor is providing useful feedback. I have run across some books where the author swears they paid a professional editor, but the book is still riddled with typos and errors. A professional editor should help polish an author’s writing, but it’s still ultimately up to the author to ensure that the manuscript is of the highest quality.

As you can see, these four revisions can potentially take up a lot of an author’s time. An author can choose to perform these revisions multiple times over different iterations of their work, depending on how much the story changes from one revision to another. Depending on an author’s revision style, they can choose to do any of these revisions in any order they want. The order I’ve presented here is what I prefer, but you can choose what works best for you. Each of these four edits takes a different approach to the revisions of a manuscript in order to hit the errors from multiple angles. Whether it’s a different set of eyes, a fresh perspective on a blank page, or engaging the auditory senses, each of these revisions helps polish a written work into something better than what it once was. It won’t be perfect, but after using all four of these revisions, your manuscript will be as close to perfect as it can get.

March 6, 2018

3 reasons why you shouldn’t pick sides

Just like everyone has a bellybutton, we all have opinions. However, if the 2016 election has taught us anything, it’s that most people’s opinions seem to be on extreme ends of the spectrum. I know you can’t please all the people all of the time, but as writers who want to sell books, we should at least try to remain unbiased. Sure, our beliefs will usually leak through into our writing. If we leave it at a subconscious level, this amount of bias isn’t too bad. When a writer tries to take a purposeful stance on something via their fiction, most of the time it falls flat and fails to convince anyone to change their mind. Here are three reasons why writers should try to be neutral in their narrative:

Opinionated writing appears preachy

I get it. The world is a mess, and we all want to blame someone for it. In these trying times, it’s easy for writers to mount their soapbox with pen in hand and let everyone know what’s what. Of course, most things in life aren’t black-and-white. There are subtleties that most opinionated writers will omit to prove their point. As a reader, when the writer clearly defines their opinions in their writing, it distracts from the story. We no longer feel immersed in a world. Instead, we feel like the writer is preaching at us with a megaphone.

If the writer is trying to appeal to those who agree with them, then everything’s fine. However, if a work of fiction is to reach a broad audience, there’s a chance someone with differing opinions could pick up the book and immediately disagree with the writer. In fact, having their beliefs attacked may result in the backfire effect. At its best, the person might never finish reading the book. At its worst, the reader may leave a scathing review because the writer was vehemently against the things the reader believes.

At this point, you may be wondering about satire. While most satire can be considered “preachy,” the best forms of satire take opinions and situations to their logical extremes. Most of us will recognize the initial consequences of a particular set of beliefs, but satire takes these consequences and iterates a few more times to show how ridiculous the world could become. Classic pieces of satire like Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 or Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle take something that’s wrong with the world and extrapolate it out to an almost inevitable conclusion. By pulling this thread to its logical end, satire manages to avoid being whiney and instead shines a harsh light on a potentially slippery slope.

Characters are stereotypes instead of archetypes

Many times, the opinions of the writer come through via their characters. Even the narrator, which should be the most neutral character in a book (especially when written in 3rd person) can expose the writer’s biases. The most apparent way characters can reveal the author’s true intentions is if they are stereotypes. While most stereotypes are based at least somewhat on factors that ring true, they are usually used in fiction as an oversimplification. Furthermore, many stereotypes can be hurtful, which again links back to your audience: do you want the people who identify with these stereotypes to enjoy your book?

I think it’s important to distinguish between stereotypes and archetypes here. Archetypes are fine, as they usually define a character and their motivation, even if this particular character has been written in numerous contexts before. Common archetypes like the “hero,” the “villain,” or the “damsel in distress” will act in a certain way because their goals are usually the same across many different works of fiction. The hero wants to save, the villain wants to destroy, and the damsel in distress wants to be rescued. Granted, some of these archetypes can be stereotypes as well, but writers need to make sure they walk that fine line between hateful stereotypes and common themes to help define a character.

In the end, the characters a writer employs in their story should appear real. If they’re just cardboard cutouts and punching bags for the author to express their frustration, then the story won’t be nearly as entertaining. Just like satire takes consequences of actions to their extremes, even characters in a story must have a logical action and reaction to their surroundings. If the characters are stereotypes, what made them into stereotypes? Upbringing? Tragic backstory? External events? When these actions that lead to the consequence of a stereotype are explored, suddenly the character becomes well rounded and less of a stereotype.

Write what you don’t know

Even though the idiom of “write what you know” helps to fill your stories with the realism that experience can provide, when it comes to opinionated writing, it’s actually a handicap. We all want our opinion to be the right one, but if the opposition in this debate is comprised of simpletons, then the reader is only receiving one side of the story. I’m not advocating for writers to write about topics they know nothing about. Instead, I’m suggesting that writers become informed and educated about the opposing opinion so they can present both sides in an equal and unbiased manner.

When an author takes a particular side on a topic, many plot holes can start to appear in the story if they haven’t considered the other side’s arguments. I know they want their opinion to seem correct, but if they’re forcing the plot to meld to their beliefs, cracks start to appear. Worldbuilding can be a challenge in fiction, but the closer it mimics a reality a reader can recognize and relate to, the easier it is for the writer to engage said reader. If anything, forcing an opinion onto a story merely highlights some of the author’s ignorance.

I’ve read a lot of books recently that have obvious opinions on many topics. I just have to roll my eyes at how preachy these narratives are. However, one book stood out because the author managed to create characters with differing opinions and gave them the opportunity to have a civil debate about their beliefs. The Infinet by John Ackers still had moments that felt biased, but he managed to provide rebuttals to these biases via his characters’ beliefs. By the end of the book, nobody had changed their opinion on anything, but it gave me plenty to think about when it came to some of these controversial topics.

When it comes right down to it, there will always be controversial topics. Religion, politics, and money are usually the topics we try to avoid to prevent a confrontation in real life. Some authors will take this as a challenge to create a world where only one side of the equation is present, which will likely alienate many readers. I’m not suggesting we don’t ever write anything about controversial topics. I’m merely suggesting that, just like in real-life, we get all the facts and provide a neutral space to discuss these challenging ideas in a fictional context. After all, letting someone come to their own realization is much more satisfying than shoving that realization down their throat.

February 6, 2018

Expectations and a Reviewer’s Rubric

When I first started my website, www.benjamin-m-weilert.com, I knew I wanted it to be a repository of reviews for all the books I’ve read and all the movies I’ve seen. I have some of these reviews scattered across the web, but I wanted a single location where all of them could reside. A single place where I could control these reviews. Now that my website is almost a year-and-a-half old, I have accumulated over 250 reviews on it. These reviews range from nights at the Colorado Springs Philharmonic to audiobooks to movies to books received from authors and/or publishers.

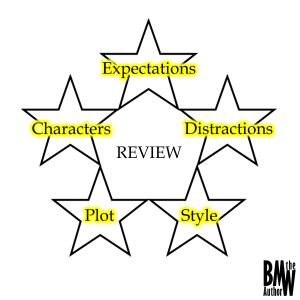

As most of my reviews, I provide a “star” rating to help visitors to my site determine if the piece of media is worth their time. Early on, I based most of my ratings on an intuitive “hunch” of what I felt the work deserved. This scale (from 0.0 to 5.0) is mostly subjective and, while this is still largely the case, by now I’ve codified much of why I provide the star ratings I do, distilled down to a few different criteria. I’ll explain this “Reviewer’s Rubric” later, but first I need to explain how many of these ratings are based on a single idea: expectation.

The expectation for a movie or book will bias a review.

It has been said, “You can’t judge a book by its cover.” While I understand it idiom is primarily applied to people’s appearances, I have found that it’s not entirely accurate for books and movies. As the cover of a piece of media needs to sell it, many expectations and biases are formed right from the first glance. Of course, while I appreciate the critically-acclaimed movies that win plenty of awards, sometimes I just want to sit down with a screwball comedy and laugh. This is where expectations come into play. If I’m expecting something to be great, I’ll be disappointed if it’s not. Conversely, if I know the movie or book I’m getting into shouldn’t be taken seriously, I’m usually satisfied if it entertains me. After all, the main reason any of us picks up a book to read or sits down to watch a movie is whether or not we’re expecting to be entertained.

Therefore, if I give a movie like The Jungle Book (2016) 5.0 stars, it’s likely for a different reason than the 5.0 stars I’d give to Interstellar (2014). Both movies received these ratings, but for different reasons. The Jungle Book is an amazing, if not superior, adaptation of an animated classic, whereas Interstellar is an emotionally-moving sci-fi epic with a mind-bending twist. In both cases, I went in with certain expectations based on what I knew of the films from previews and trailers, as well as the cast and crew that made them. The reason both of these films deserve 5.0 stars, in my opinion, is likely due to how they surpassed my expectations. If they had just met my expectations, they’d likely sit at a 4.0 or 4.5 rating. Of course, the reverse is true as well: if the movie failed to meet my expectations, it would receive a poor rating.

Books or movies with the same rating may have it for different reasons.

As it turns out, “Expectations” is the foundation for each of my ratings. It usually influences the review heavily but is also informed by four other categories: Characters, Plot, Style, and Distractions. Each of these sections is a little different for books, as compared to my movie reviews, so let’s go through them separately . . .

MOVIE:

Expectations – Since the majority of movies I watch are produced by Hollywood or are classics identified in books like 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, my expectations for these films are usually pretty high. This is because my bias comes from outside sources that will indicate whether or not a movie will be “good.”

Characters – Are the characters likable? Are they realistic? Do I care about these characters?

Plot – Does the plot (and its twists) make sense? Is it realistic? Am I struggling to stay awake during the film?

Style – This mostly applies to the cinematography, but the “visuals” provided by CGI often influences this section.

Distractions – Is the acting too over the top? Are the jokes consistently low-brow or lame? Are there unnecessary elements that distract from the core of the movie?

The 5 elements of a Review

The 5 elements of a ReviewBOOK:

Expectations – For most books, the title and cover set much of my expectations. If an author or publisher sends me a novel comparing it to a famous/popular one, then I expect that it will be at least as good as the one they’ve compared it to. This is rarely the case. So, word of caution to authors out there: if you compare your book to a bestseller, be prepared to underwhelm your readers.

Characters – Are the characters likable? Are they realistic? Do I care about these characters?

Plot – Does the plot (and its twists) make sense? Is it realistic? Am I struggling to get through it and just want to quit reading?

Style – Is the author’s writing easy to understand? Are the author’s biases and beliefs blatantly apparent through their writing? Are they “elitist?” Is the prose clunky and/or annoying?

Distractions – This one is huge. Most of the sub-par ratings I give are because of this category. What’s unfortunate is that these distractions are easy to fix if you have a good editor and formatter. A short list of these distractions falls into two sub-categories . . .

Proofreading: Spelling, homophones, punctuation, and grammar.

Formatting: Justify-align not used, too many blank pages, weird gaps, inconsistent section break markings, and no first-line indents.

As you can see, there are a few similarities between the two rubrics. Because there are five categories, you can generally equate each of those to a single “star” of the rating. Sometimes the strength of one of the categories (like “Style,” for instance) can overcome one of the weaker categories (usually the “Distractions” category).

Of course, one of the most significant differences between the movie reviews and the book reviews comes from my experience as an author. I don’t have any experience making movies, so I’m usually pretty lenient and will usually rate a little higher than average for films when compared to books. This is because I know what it takes to make a good book, and that’s probably the base of my expectations. If a book doesn’t match up with my self-imposed standards for my writing, then there’s room for improvement which I usually detail in my review.

Even an atrociously bad book or movie will receive 0.5 stars.

With all this being said, what about the 0-star reviews? If I can make it all the way through a book or movie, the lowest rating it will receive will be for 0.5 stars. I have a reasonably high tolerance for bad books, so I will often suffer through to the end of a book. This is so I can give a review of the entire work. After all, it’s not fair to the author if the “hook” for their book isn’t good enough to grab my attention, but the story and characters become interesting later on. Alternatively, if the “hook” is good enough, but the story peters out, and the characters start to grate on me, I’ve usually invested enough time into the book that I’ll finish it out of spite. There have been some books I should have stopped reading, but didn’t, and I’m learning my time is worth more than that. So, if I cannot make it all the way through a book, I won’t give it a star rating, but I will review it to lay out the reasons why I could not finish. After all, the star ratings do affect a book’s rankings on sites like Goodreads and Amazon, so I don’t want to skew those metrics on a book I didn’t even finish reading.

I will once again iterate that my Review Rubrics are more guidelines for my ratings, and I will usually put some verbiage in my reviews that highlight which of the five categories I thought the book or movie excelled in or needed to improve. When it comes right down to it, a lot of the rating is just finding a number that “feels” right, but with the reasoning to back it up.

BMW the Blog

- Benjamin M. Weilert's profile

- 27 followers