Tansy Rayner Roberts's Blog, page 132

September 28, 2011

Brutus/Cassius: Men of Rome!

I did not know there were such things as Brutus/Cassius fanvids in the world, but there are, there really are! Not just thanks to any recent revival in sexy Roman TV drama, either.

I did not know there were such things as Brutus/Cassius fanvids in the world, but there are, there really are! Not just thanks to any recent revival in sexy Roman TV drama, either.

Shakespearean Brutus/Cassius.

Don't believe me?

and also

Matrons of Awesome Part VII – Sex, Scandal & Bloodshed

When Tiberius died, he was succeeded by the very young and very unstable Caligula. Caligula had three older sisters: Livilla (not the previous Livilla, sometimes called Julia, not any of the previous Julias), Agrippina and Drusilla, whom he heaped with public honours (honours not extended to his various wives, not even the mother of his baby). He had the names of his sisters included in the formal oaths, so that when Romans swore in the name of the Emperor they were also swearing in the name of his sisters.

Caligula's favourite sister was Drusilla. Their grandmother Antonia had been shocked to find them in bed together as children, in a very non-siblingy kind of way. As emperor, Caligula infamously ravished all three of his sisters at official banquets. (it passes the time between lark's tongue & pudding)

All sources suggest that Caligula was a bit loopy. He made strange public declarations (for instance, that he was the god Jupiter, or that the newest member of the Senate was a horse). He set up temples to himself, treated his wives with extreme cruelty, and indulged in cruel and bloodthirsty entertainments.

As Emperor, Caligula established Drusilla as his consort ("treating her openly as if she were his wife," cough cough), and also his heir. This begs a very interesting alternate history what-if, as it is the only time that a woman was officially named as an heir to the Empire.

But it was Drusilla who died: young, and suddenly.

(there is no historical evidence for the Robert Graves version of these events, where John Hurt's Caligula finds out Drusilla is pregnant with his baby and, in true godly fashion, decides he needs to cut the baby out so that it will not be greater than him… or some such nonsense)

Caligula was crazed with grief. He made it a public offense to laugh, bathe or dine with one's family for as long as the mourning period lasted. And then he made Drusilla a goddess. She was the first imperial woman to receive this honour (their great-grandmother Livia had to wait until the next reign to be deified) and, indeed, Drusilla was only the third Roman ever to be made a god, after Romulus (the first king, remember him, the Sabine-raper) and Augustus.

For the rest of his life, Caligula swore all oaths by the divinity of his sister, and no one dared challenge this assertion. The main reason Drusilla is remembered today is because he ensured that Rome remembered her.

Caligula died without heir. His baby daughter was killed in the conspiracy that also assassinated Caligula himself. For a moment, it looked like a return to the Republic was the only option… but the Palace Guards, desperate to keep their jobs by making sure there was someone on the throne, found themselves another emperor.

Stammering, sickly Uncle Claudius – brother of Golden Germanicus and the Livilla who got herself walled up and starved to death, son of strict Antonia and popular Drusus, grandson of Livia and Octavia and Mark Antony, great-nephew of Augustus. Claudius had always been left out of the succession because of his physical failings, which made people assume he was stupid. He wasn't. He was a scholar, and an excellent tactician. But when it came to women… oh, yeah. Stupid.

When Claudius was found cowering behind a curtain and forced on to the throne, he was married to his third wife, the young and vivacious Messalina. She adored the spotlight that fell on her when her husband unexpectedly became Emperor. It was all statues, portraits, gorgeous frocks and excellent parties. Her two small children were likewise celebrated.

Sadly, that isn't why Messalina is remembered. The adultery saw to that.

Not just any adultery. According to the stories (brought to you, I must admit, by the same historians who were convinced that Livia poisoned every relative of Augustus' who died over a fifty year period), Messalina made sex into an art form. She reputedly once challenged a famous prostitute to a contest as to whom could bonk the most men in one night, and out-shagged her with flying colours. She set up a brothel among the upper classes, so aristocratic husbands could pimp out their wives.

Funnily enough, it wasn't sex that was Messalina's downfall. It was lurve. And, you know, UTTER STUPIDITY.

Her latest lover was Silius, and she was so enamoured of him that she kept giving him presents. Little trinkets that she found lying around the palace – the Emperor's furniture, slaves, shiny things. And then she though, "Oh, gosh, I love Silius so much, why don't we get married?"

So she waited until her husband Claudius was out of town, and she did it. Those crazy kids got married. Not just bigamy, but Treason with a capital T.

Messalina wasn't the only confused one. Apparently, when Claudius hastened back to town after being told the news, he wondered aloud, "Am I still emperor?" He vacillated between punishing Messalina and forgiving her – and his advisors were so worried that he would come down on the side of forgiveness that they had her executed by the sword themselves, and told him it had been his idea.

As the ultimate example of female transgression in Ancient Rome, Messalina is also one of the most famous Roman women. She has been portrayed on stage, screen and in literature and artwork. In biblical epics like The Robe and Demetrius and the Gladiators, she is presented as a symbol of Roman decadence (as opposed to Christian morality). In truth, the Romans were about as conservative and po-faced as the Christians later were; figures like Caligula and Messalina were exceptions, not the rule.

In I Claudius, both the Robert Graves book and the BBC mini-series, Messalina is portrayed as being almost child-like in her naivete as well as dangerously sexual. In Italian cinema, her story is in the realms of pornography.

This popular version of Messalina as the slut who couldn't say no is so powerful that it is impossible for us to learn anything else about who she was as a person and a historical figure. Even the majority of her portraits from the time before her reputation was ruined are lost to us, because they were destroyed after her execution. We don't know what kind of power and position she had as the wife of the emperor; what her childhood was like; who her friends were. All we know is that she was (according to the accounts that survived) promiscuous, and punished accordingly.

We know little about Calpurnia, mistress of Claudius, except that she was an intelligent woman who advised him well. When the various court toadies and ministers found out about Messalina's second marriage, they were so scared of telling the emperor themselves that they went into the slum area where Calpurnia lived and begged her to be the one to break the news, on the grounds that Claudius would believe her above the rest of them. (but, in truth, they were probably hedging their bets in case he went wild and started chopping heads). I get the impression that she was a sensible, placid sort of woman, and that Claudius would have been way better off if society allowed him to marry someone like her.

Instead, after the train wreck that was his marriage to Messalina, he decided to choose his next wife based on experience and good genetics.

So he married his niece.

=====

The Matrons of Awesome series was originally posted on Livejournal (LJ user: cassiphone) in March 2006 for Women's History Month.

The Matrons of Awesome series was originally posted on Livejournal (LJ user: cassiphone) in March 2006 for Women's History Month.

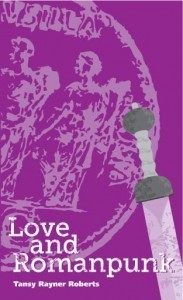

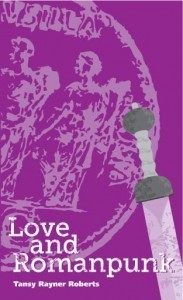

I'm reprinting the series as part of my Rock The Romanpunk week in celebration of my short story collection, Love and Romanpunk, which was published by Twelfth Planet Press earlier this year and is now available globally as an e-book as well as a pretty imperial purple print edition. Thanks to Wizard's Tower Bookstore you can also now purchase it for the Kindle.

Matrons of Awesome Part VI – Imperial Daughters and Many Small Islands

11. Antonia

11. Antonia

(sometimes called Antonia Minor because she had an older sister also called Antonia, though the other one never did much interesting – maybe ours should be named 'Antonia the More Interesting Than Her Sister)

Daughter of Octavia and Mark Antony, Antonia was a quiet, austere woman who rose in status almost equal to that of Livia.

She was married to Drusus, Livia's son (the cute one) and they had three children: golden Germanicus, limping, stuttering Claudius and lusty Livilla. Antonia was widowed at 27, and refused to remarry, despite the fact that Uncle Augustus had brought in a law that widows had to remarry within a year.

Antonia was a tough mother, and we have correspondence that shows how bitterly disappointed she was in young Claudius' failings. Also, when daughter Livilla was caught out for being involved in a conspiracy against the Emperor Tiberius, Antonia is said to have personally walled her up in a room and starved her to death.

It was Antonia who discovered the conspiracy (of Sejanus, played in the I Claudius series by a devilishly young and curly-haired Patrick Stewart, oh yes he did) and revealed it to the Emperor. She was credited with saving the empire.

Antonia survived the reigns of Augustus and Tiberius, and made it as far as the next Emperor, scary crazy Caligula, the son of her late son Germanicus. Caligula gave his grandmother a heap of honours, including the title 'Augusta' which had previously only been held by Livia. At least one source says that she rejected the title, which is patently ridiculous. He was giving her a cornucopia of high honours at the time, why would she risk annoying him to turn down one lousy title?

In fact, the title was re-issued to Antonia posthumously by the next emperor, her own son Claudius. It's understandable that he wanted to do this – almost no one had heard of him, and he needed to point out his place in the shaky Julio-Claudian family tree. The 'she refused it' story was obviously made up to justify Claudius giving her a title she had already been given. IMO.

Antonia died within a few weeks of Caligula's accession to the throne. Possibly poisoned by him for speaking her mind – she had always been a bit snarky with him since discovering him doing naughty things in bed with his sister when he was a child. Or maybe she just died of natural causes, being on the elderly side.

But this is the Julio-Claudian family – no one dies of natural causes!

12. Julia

12. Julia

(often called Julia Major, because her daughter had the same name, but it is also fitting because she was the first imperial Julia)

Julia was the daughter of Augustus, his only child. She was a witty, lively woman who had a tendency to get pregnant if she sat on a warm couch.

She was married three times, to her cousin Marcellus (Augustus' heir at the time), then, after his early death to mysterious fever (cough-poison-cough) she was married to Augustus' best friend and supporter, General Agrippa. He was the same age as her father.

They had at least five children: Gaius, Lucius, Agrippina Major, Julia Minor, and Agrippa Posthumus (born after the death of his father).

Several examples of Julia's wit have been recorded for history. Once, she was asked how she managed to produce children that so obviously resembled her husband, given her tendency to sleep around. She responded with: "I never take on a passenger unless the cargo is already aboard." Classy.

Her vanity was also immortalised in a scene where Augustus caught her plucking silver hairs from her head, and asked his daughter, "Which would you rather be, grey-haired or bald?"

Julia's tendency to flirt and frolic brought her to a sticky end when she was married to her third husband, her dour stepbrother Tiberius. He was so annoyed at their marriage that he ran away to self-imposed exile on Rhodes for many years, leaving Julia to amuse herself. Later, when it became convenient for him, she was found guilty of adultery and also of conspiracy, since one of her suspected lovers was a rebellious son of Antony and Fulvia.

Julia was exiled to a tiny island in the middle of nowhere, and her mother Scribonia (whom history books hadn't mentioned since she was divorced by Augustus) chose to accompany her. Julia's public downfall was a huge humiliation to Augustus, who had staked his reputation on the good conduct of the women of his family, expecting them to stand as examples for the social legislation he had brought to Rome (making adultery illegal, trying to encourage the birth rate, not letting widows and divorcees of high rank stay unmarried for long, that kind of thing).

Julia and Scribonia had a miserable time of it. When Augustus died, Tiberius cut off their allowance, and by all accounts they starved to death.

I told you there was a reason no one liked Tiberius much.

Julia's first two sons were adopted by Augustus as his heirs, but both died in their late teens, one to a fever (cough, Livia, poison, cough) and another to a wound sustained in battle (I don't really think Livia needed to do much for that one, personally, though some like to give her the credit, what with sending her "personal physician" to try and save the boy). Agrippa Posthumus was later adopted by Augustus as an heir, but was disgraced and exiled to another small island for suspected revolutionary activities and/or attempting to rape a female family member (Livilla, I think, though I could actually be imagining that one, or channelling Robert Graves). It has been suggested that Livia's motive for hastening Augustus' demise (don't you love that even at 85 and after a lifetime of ill health, the historians can't bear the thought of him dying a natural death?) is that he was thinking of forgiving Posthumus and favouring him over Tiberius.

Julia's daughter Julia Minor went down the same path as her mother – exiled to a small island (strangely, Augustus never ran out of those) after being caught out in naughty behaviour. Possibly a bit of namedropping here something to do with the poet Ovid, who was famously exiled at the same sort of time for "a poem" (possibly the one about how to pick up married women) and "a mistake" (tantalisingly, we don't know what).

Of all of Julia Major's children, only Agrippina Major made much of an impact on history of the dynasty, by surviving to bear children of her own. And what children they were… but let's not get ahead of ourselves.

Daughter of Antonia and Drusus, sister to gorgeous Germanicus and weedy Claudius, Livilla was a pawn in the imperial game from very young. She was married first to young Gaius (Agrippa & Julia's eldest son) who was Augustus' heir, so could potentially have been the second princeps femina after Livia.

Except Gaius died, so Livilla married someone else (yawn, can't remember who – oh, hang on a minute, duh, it was Tiberius's son whatsisname) and had some kids including a daughter whose name was either Livia or Livilla or Julia (but not, as Graves would have it, Helen). After that, she hung around the palace doing her nails for a few years.

Then, when dashing young military man Sejanus started sucking up to the Emperor Tiberius, and was set to become his heir and successor, Livilla fell into bed with him. Tiberius didn't think of marrying them to each other (funnily enough, what with her being married to his son already) but suggested Sejanus might like to marry Livilla's daughter. Naturally, Livilla was somewhat pissed off.

Suddenly Sejanus was arrested for treason (there's more to it than that, but this really isn't my area, blah boy politics blah, read some Tacitus if you're really interested), Tiberius having been tipped off by Livilla's mother Antonia. And Livilla, caught with her treasonous knickers down, got locked in a cupboard and starved to death by her mother.

Possibly they had finally run out of small islands.

14. Agrippina Major

14. Agrippina Major

(yep, you guessed it, mother of another Agrippina, and so on. Not a Kylie or Edith in sight of this family)

Unlike her sister Julia Minor, Agrippina did not inherit her mother's tendency to involve herself in illicit love affairs. But then, why would she? She was married to sexy golden boy Germanicus, son of Antonia the Stern and Drusus the Likeable. They were Rome's answer to the supercouple.

While Golden Germanicus travelled around with the army, earning brownie points by the bucketful for his military prowess, Agrippina marched in his wake with her many children at her side. No working in wool for this woman.

When Tiberius became emperor, Germanicus was named his heir. And what an heir! He was cheered wherever he went, rose petals were hurled at his head, slave girls were thrown at his feet… you get the picture.

Even their children were cute, particularly the youngest. Darling moppet Gaius was born in an army camp, and the adorable toddler was adopted by the soldiers as their mascot. "Little boots," they called him, for the miniature replica soldier's gear that the little cherub wore as play gear. It was a name that stuck with him for the rest of his life.

Little Boots in Latin = Caligula.

But this is Agrippina's story. When Golden Germanicus died, the world mourned with her. But Agrippina was no quiet, dignified widow like her mother-in-law Antonia. She raced home, wild-haired and wild-eyed, her children at her heels, to accuse Tiberius and his wicked mother Livia of murdering her darling husband.

But this is Agrippina's story. When Golden Germanicus died, the world mourned with her. But Agrippina was no quiet, dignified widow like her mother-in-law Antonia. She raced home, wild-haired and wild-eyed, her children at her heels, to accuse Tiberius and his wicked mother Livia of murdering her darling husband.

Because yes, Livia would kill her own grandson, who was legitimate heir to her son's Empire… that makes sense.

But Agrippina, the loyal military wife, would not be silenced.

Tiberius' famous put down on one occasion: "Is it really so offensive to you that you are not treated like a queen?"

Eventually, Agrippina stopped yelling at the Emperor's face long enough to get caught for conspiring behind his back and – you guessed it – she was exiled to a small island and executed, not necessarily in that order.

Her children remained at court, raised by their grandmother Antonia. Eventually, Caligula was named as Tiberius's heir, despite already showing signs of being somewhat deranged.

I'm pretty sure it was Robert Graves rather than any of the ancient sources who came up with the best reason why Tiberius would hand his Empire over to Caligula: the only way to be remembered as a Good Emperor is to be succeeded by a Really, Really Bad one.

Oddly enough, it worked quite well. But don't try this at home, kids.

=====

The Matrons of Awesome series was originally posted on Livejournal (LJ user: cassiphone) in March 2006 for Women's History Month.

The Matrons of Awesome series was originally posted on Livejournal (LJ user: cassiphone) in March 2006 for Women's History Month.

I'm reprinting the series as part of my Rock The Romanpunk week in celebration of my short story collection, Love and Romanpunk, which was published by Twelfth Planet Press earlier this year and is now available globally as an e-book as well as a pretty imperial purple print edition. Thanks to Wizard's Tower Bookstore you can also now purchase it for the Kindle.

September 27, 2011

Matrons of Awesome Part V – Romana Princeps

There are some historical characters you just become unreasonably attached to. Livia is my sweetie. Warning: you're not going to get a balanced academic opinion on this one. (it was hard enough doing that in my thesis)

When Livia met Augustus, they were both married to other people. He had a daughter, and she was pregnant with her second son. Within a few months of meeting each other (round about the time Antony and Octavia were getting married), they had divorced their respective spouses and were shacked up together. They got married almost immediately after she had her baby.

Does that sound like a relationship that happened two thousand years ago? Nope, me neither.

Livia never bore Augustus any children. There is no cited reason for this – they had both had children with their previous spouses. But she did suffer a miscarriage early in their marriage, which could have led to physical complications. What is interesting is that despite Augustus' desire for a male heir of his body, he never divorced Livia to get a wife who would bear him a son. She was far too useful to him as a wife. HEAR THAT, HENRY THE EIGHTH?

After Livia's first husband died, her two sons, Tiberius and Drusus, came to live in Augustus and Livia's household. She also fostered various children. Ultimately, it was her Tiberius who succeeded Augustus as emperor.

In the literary sources Tacitus and Suetonius (and the iconic novel I Claudius by Robert Graves), Livia is portrayed as a manipulator, a poisoner and an ambitious mother. The premature deaths of many of Augustus' male heirs (his nephew, several grandsons) are attributed to her, as are the public downfalls of many of his female relatives, including his daughter Julia, who was exiled for adultery and intrigue.

Both Tacitus and Suetonius are openly misogynistic in their writings. They were both published a century or so after the reign of Augustus, and their main priority was to show how modest, chaste and non-murderous the women of the current imperial dynasty were in comparison to their wicked predecessors.

By the time they get to "Livia sent her personal physician to the boy wounded in battle and he mysteriously died (cough, septicemia, cough)," or "she murdered her own grandson because he was more popular than her son," or "she murdered her own husband after 50 years of marriage because he was maybe going to forgive one of his disgraced former heirs in favour of her son," well, my eyebrows get tired from being raised so much. It's such a blatant hatchet job on her reputation.

Having said that, if the sources are right and Livia was actually a controlling, manipulating, murderous and ambitious bitch from hell? She apparently kicked arse at it.

During his reign, Augustus promoted Livia as a public example of the ideal wife: working in wool (she had a whole household of slaves to do this for her), dressing modestly, behaving chastely. He publicly stated that husbands should guide their wives in proper wifely dress & behaviour, which the senators all thought was hilarious – when they asked him how they should actually go about this, he looked a bit vague and suddenly pretended he had to be somewhere else.

According to rumour, Livia used to supply slave girls for her husband's bed. Which is also proper wifely behaviour, apparently.

Livia was one of Augustus' main advisors throughout his public career. They were a partnership in a truest sense of the word. As the first emperor, Augustus had many titles, but there was no title or word that meant 'wife of the emperor,' no 'empress' or 'queen' for Livia or any other imperial wife. The term femina princeps (first lady) was used by the poet Ovid, and the term Romana princeps (first Roman lady) was also unofficially used for Livia.

There's also Augusta, but we'll get to that in a bit.

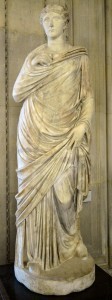

There are many portraits of Livia. This is my favourite. I fell in love with it in photographs, then had the extraordinary good luck to be able to visit her personally. Never mind the Mona Lisa, this is the Louvre's greatest treasure. She is way more beautiful in person than on the page. I spent a long time trying to get the right photo to capture her, but it's impossible. The basalt just glows in a way that a photo can't convey.

There are many portraits of Livia. This is my favourite. I fell in love with it in photographs, then had the extraordinary good luck to be able to visit her personally. Never mind the Mona Lisa, this is the Louvre's greatest treasure. She is way more beautiful in person than on the page. I spent a long time trying to get the right photo to capture her, but it's impossible. The basalt just glows in a way that a photo can't convey.

If you're ever in Paris, say hi to her from me.

After the loss of so many of Augustus' heirs, Livia convinced him to make his daughter Julia (twice a widow) marry Livia's eldest son Tiberius, in order to promote him as an heir. She forced Tiberius to divorce a wife he loved (Vipsania, Julia's stepdaughter, a bit like the Bold and the Beautiful, isn't it?) in order to expedite this. It worked, though Tiberius and Julia hated each other.

No one actually liked Tiberius all that much, including his mother Livia. Her younger son, Drusus, was the one who got along with everyone (though he was, gasp, a Republican). Drusus was married to Antonia, daughter of Octavia and Mark Antony. Their children included Germanicus (another golden boy, beloved by all), Claudius (a cripple & stutterer, believed to be mentally deficient) and Livilla (a little too popular with the boys).

When Drusus died, everyone was devastated. A famous poem, Consolatio ad Liviam, was written in honour of Livia as the dead man's mother. Livia was awarded the honorary honour of 'mother of three children' despite only having two that lived. She invited her widowed daughter-in-law Antonia to move into her household.

Towards the end of Augustus' life, he adopted Tiberius (his own stepson/son-in-law) as his son and heir (on condition that the shiny and fabulous Germanicus be named as his uncle Tiberius' heir, despite the fact that Tiberius had a son and grandson of his own). Tiberius was officially the Last Turkey in the Shop but he had stayed the distance, and outlived everyone else.

(No one ever suggested that Tiberius had bumped off all his male relatives – no, no. They blamed his mother for it.)

Augustus was in his eighties when he died. According to rumour, this one was down to Livia too. He became paranoid that he was being poisoned, and ate only the food he picked himself. So she poisoned the olives on the tree.

It's a very good story, but I don't believe a word of it.

In his will, Augustus posthumously adopted Livia as his daughter, (Bold and the Beautiful, eat your HEART out), giving her the name Julia Augusta. Julia/us was his family name, and Augusta the feminine equivalent of his own name/title Augustus. No source has ever stated what 'Augusta' was meant to mean, or whether it held any power as a title, but it became an honorary title given to many imperial women over the years. My PhD thesis, for those of you still interested, was on trying to figure out what the title meant, based on the women it was given to.

As Julia Augusta, mother to the emperor, Livia also became the widow of a god when Augustus was deified, and she was named priestess of his cult. The people of Rome saw her as her dead husband's representative, and she was seen on many occasions acting as if she was still the 'Romana princeps'. Indeed, she was still the First Lady of Rome, as Tiberius had no wife during his reign (Julia had been exiled for adultery).

The Senate offered Livia many other honours, including an arch (which Tiberius never built) and that Tiberius be officially known as son of Julia (which Tiberius refused). Oh, and the title Mater Patriae (Mother of the Fatherland, an exercise in gendered irony or ironic gendering) which Tiberius refused on her behalf.

Really, there's a reason no one liked Tiberius very much.

Here's the best argument against all those poisonings and machinations: Augustus respected Livia, and listened to her advice. Tiberius didn't. Livia had far more power (however uncredited) during her time as the imperial wife of Augustus than her time as the imperial mother of Tiberius. So if she did murder a bunch of people including her husband to get there, then it was a tragic waste of her time and effort.

Tiberius did, however, put Livia on the coinage. Possibly. There are three coin portraits which are almost certainly representations of Livia, though they claim to be personifications of Iustitia (Justice), Pietas (Piety) and Salus Augusta (Health of the Augustan Family). They don't have her name on them, or anything, but they kind of look like her. From a certain angle.

Tiberius did, however, put Livia on the coinage. Possibly. There are three coin portraits which are almost certainly representations of Livia, though they claim to be personifications of Iustitia (Justice), Pietas (Piety) and Salus Augusta (Health of the Augustan Family). They don't have her name on them, or anything, but they kind of look like her. From a certain angle.

Livia died in her eighties. Neither her son Tiberius nor his successor, Livia's great-grandson Caligula, allowed her to be deified like her husband. Good old bumbling Claudius, however, whom Livia had described in her own correspondence as a fool and a cripple, saw fit to make his great-aunt a goddess. Divus Augustus and Diva Augusta shared a temple and a priest, and were commemorated on the coinage. Unlike many other 'homegrown' gods, they were worshipped and remembered for many imperial reigns after their own shared dynasty died out.

Robert Graves' novel "I Claudius" is often praised for being so well-researched. In fact, what he did was take Roman historians Suetonius and Tacitus at face value, then added a bit more in the way of dialogue, characterisation and a few extra scandals.

Robert Graves' novel "I Claudius" is often praised for being so well-researched. In fact, what he did was take Roman historians Suetonius and Tacitus at face value, then added a bit more in the way of dialogue, characterisation and a few extra scandals.

His Livia is unrepentantly manipulative of her family – she poisons more people than even the historical sources suggested. In the BBC miniseries based on the book (with Derek Jacobi as Claudius, Brian Blessed as Augustus), Sian Phillips steals the show as Livia, an aging superbitch of epic proportions.

The evil, calculating and ambitious queen that Tacitus and Suetonius and Graves believed in is brought to life magnificently by Sian Phillips, and while I don't believe that Livia really existed, I like her almost as much as the one I feel is more historically credible.

At the far end of the credibility scale, we have Xena: Warrior Princess, a show that gave us women of colour playing both Cleopatra and Helen of Troy, a surfing Valley Girl Aphrodite, vampiric goth girls as Bacchae, a Caligula who actually was a god, and an unforgettable Ares in black leather. In the Xenaverse, Livia (Adrienne Wilkinson) is actually Xena's daughter, a warbitch and fierce lady general. Separated from her mother at birth, she is adopted by Octavian as a baby, which is creepy beyond words and yet… there's a seed of real history there for which, kudos. As his mistress and the general of his brutal armies, she regularly goes around wiping out Amazon tribes and growling at the camera. I find this version of Livia utterly hilarious, and I love her too.

At the far end of the credibility scale, we have Xena: Warrior Princess, a show that gave us women of colour playing both Cleopatra and Helen of Troy, a surfing Valley Girl Aphrodite, vampiric goth girls as Bacchae, a Caligula who actually was a god, and an unforgettable Ares in black leather. In the Xenaverse, Livia (Adrienne Wilkinson) is actually Xena's daughter, a warbitch and fierce lady general. Separated from her mother at birth, she is adopted by Octavian as a baby, which is creepy beyond words and yet… there's a seed of real history there for which, kudos. As his mistress and the general of his brutal armies, she regularly goes around wiping out Amazon tribes and growling at the camera. I find this version of Livia utterly hilarious, and I love her too.

You see? It's even worse than my crush on Julius Caesar. I am, indeed, a hopeless case.

But I want it on record that I didn't name a daughter after this one.

=====

The Matrons of Awesome series was originally posted on Livejournal (LJ user: cassiphone) in March 2006 for Women's History Month.

The Matrons of Awesome series was originally posted on Livejournal (LJ user: cassiphone) in March 2006 for Women's History Month.

I'm reprinting the series as part of my Rock The Romanpunk week in celebration of my short story collection, Love and Romanpunk, which was published by Twelfth Planet Press earlier this year and is now available globally as an e-book as well as a pretty imperial purple print edition. Thanks to Wizard's Tower Bookstore you can also now purchase it for the Kindle.

Mark Antony: Man of Rome!

I've always been Team Caesar rather than Team Antony – but James Purefoy's performance in HBO's ROME almost made me change my mind. Almost, I say, none of that smirking, Random Alex!

If ever there was a man who rocked the Romanpunk, it was this one.

[Your mileage may vary as to whether this vid is worksafe or not! I'm pretty sure he loses more clothes than this, so save it for later if you're unsure]

September 26, 2011

Matrons of Awesome Part IV – Good and Evil at the End of the Republic

You may have noticed by now that Roman women tend to be classified as either Good or Bad. I used to think this was significant until a good friend and fellow scholar pointed out that Romans categorise everything this way. Men, women, emperors, fictional characters, countries. Everything is either Good or Bad.

The work I did over the three thousand years or so it took to complete my PhD thesis (okay, seven) revolved a great deal around the Roman idea of what constituted Good and Bad women. Lucretia and Cornelia on one side, Clodia and Fulvia on the other. The women of this post, however, provide some of the best examples of this division.

Julius Caesar, Marble, c. 50 BCE, Vatican Museums

A brief history lesson first: Rome was a Kingdom, then a Republic, the latter being a political system best described as 'every rich man gets a vote'. Then, in a time when the Republic was falling to rack and ruin, a popular man. He had some good ideas about how to run Rome and the growing empire of territories it had conquered. He became high priest (pontifex maximus), then Dictator (a short-term position brought in occasionally when shit needed to get done). Finally, he was made Dictator for life. He was the only one that Rome trusted to actually Get the Job Done. He also looked good in tight jeans. (shut up, this is my version of the story) His name was Gaius Julius Caesar.You may have guessed, I'm a bit of a fan.

Caesar's Achilles heel was that he tended to assume everyone was (almost) as smart as he was, and that the world would see that he was trying to save Rome, get shit done, etc. But success breed jealousy, and many of his peers resented his a) smarts b) popularity c) saucy Egyptian mistress.

Because, yes, Caesar had visited Egypt to borrow their navy and ended up in bed with their Queen. His dalliance with Cleopatra, and other less than subtle reminders of his new power sent off warning bells in the heads of many of his fellow senators. (the ones whose power he had effectively usurped…)

Remember Lucretia? She was used as an excuse to kick the kings out of Rome. Now, hundreds of years later, Roman society had a horror of kings – a group paranoia about returning to the Bad Old Days. When Caesar's good pal Antony offered him a crown in public (though Caesar refused it, theatrically), rumours began that Caesar planned to overturn the Republic and become a King.

Karl Urban as Julius Caesar in Xena: Warrior Princess (1999)

Ironically, the word 'dictator' had none of the connotations it does now, but 'rex' (king) was enough to put fear into the hearts of a whole city. Or, at least, the hearts of the rich white men who were used to being allowed to vote.So a bunch of senators got together and stabbed Caesar to death.

All well and good (sob!), but they had failed to notice that the Republic was already dead. Caesar's work was left half done, and their train wreck of a political system couldn't snap back into place. The people looked for a replacement, and they found two: Caesar's best pal Antony (a lush and a flake), and Caesar's great-nephew and heir Octavian (had the right kind of evil smarts, but too young to be taken seriously). Together they hunted down Caesar's assassins, and ended up trying to jointly rule an Empire. Only trouble was, they didn't like each other very much.

Yay team!

Aureus of Mark Antony, featuring portrait of Octavia, 38 BCE

8. OctaviaOctavia was Octavian's sister, a good and modest widow with several children. When Fulvia died (Antony's "virago" of a wife, remember!) Octavian saw a chance to cement his uncomfortable alliance with Antony by marrying him to his sister. It worked, for a little while. They even released coins in commemoration of the friendship between the three of them.

(note: the bit in HBO's Rome where Antony was shagging Octavia and Octavian's mum was, sadly, completely fictional. Not even a scurrilous rumour at the time. Sorry, Atia. You just weren't as awesome in history as you were on TV)

But while Octavian busied himself in Rome, Antony took on some of the more interesting outer reaches of the Roman Empire, regularly leaving his wife at home with their various children (his by Fulvia, Octavia's by her first marriage, plus an expanding crop of their own, like a Roman version of the Brady Bunch) to bury himself in the wealth, luxury, politics and Queen of Egypt.

That's right, Antony had taken up where Caesar left off with Cleopatra.

Octavian became more and more nervous – Cleopatra had wealth, resources and a kick-ass navy. Rome had empty coffers. If Antony chose to turn the power of Egypt against Rome… well, it all looked pretty damn terrifying. Then Antony sent Octavia a letter, announcing that she was divorced. The last tie between Antony and Octavian had been broken, and war was imminent.

But while soldiering was not Octavian's superpower, political propaganda absolutely was. He did some of his best work on Antony, who became known as the shiftless sucking-up-to-foreigners traitor, while Octavian remained a virtuous and loyal Roman. Likewise, Cleopatra was portrayed as an evil, luxury-loving slapper while the abandoned Octavia was presented as the best and most modest of Roman women…

But while soldiering was not Octavian's superpower, political propaganda absolutely was. He did some of his best work on Antony, who became known as the shiftless sucking-up-to-foreigners traitor, while Octavian remained a virtuous and loyal Roman. Likewise, Cleopatra was portrayed as an evil, luxury-loving slapper while the abandoned Octavia was presented as the best and most modest of Roman women…

And yes, Octavian really was that good, because this propaganda still deeply affects the way all these people are remembered today.

Though to be fair, I think he had Antony right on the money, JUST SAYING.

While Antony was bonking a queen and revelling in the luxury of her court, Octavian planned a dynasty of his own. He heaped honours upon his sister Octavia and wife Livia, giving them a public identity through the (incredibly rare for women) right to be portrayed on statues. He named Octavia's eldest son from her first marriage, Marcellus, as his heir.

While Antony was bonking a queen and revelling in the luxury of her court, Octavian planned a dynasty of his own. He heaped honours upon his sister Octavia and wife Livia, giving them a public identity through the (incredibly rare for women) right to be portrayed on statues. He named Octavia's eldest son from her first marriage, Marcellus, as his heir.

There was a war, eventually. A civil war, really, because Antony's troops were as Roman as Octavian's – but propaganda came to the fore again, and Octavian made it clear that his men were fighting a war against the decadent Queen of Egypt, not their fellow Romans. It ended badly for Antony and Cleopatra, who both died as a result.

Octavia continued in public life as the mother of Octavian's's heir. After Antony and Cleopatra's children were marched in the streets as prisoners of war, Octavia quietly took them into her own household along with their various half-siblings. Just like that episode where Marcia, Jan and Cindy had to share their room with the Egyptian princess who worshipped Isis!

Oh, what fun they had.

Later, when Marcellus died young, Octavia was so wracked with grief that she withdrew from public life, leaving Octavian (who had renamed himself Augustus, another masterstroke of PR) to find other women to promote as the Ideal Roman Matrona within his family.

She was always remembered as a Good Woman, even long after Antony or Octavian ceased to be politically relevant. But no one ever mentioned if she was happy.

Foreign vs. Roman has always been a key indicator of virtue to the Ancient Romans, but never so much as during the period when Octavian/Augustus Caesar ruled Rome. (PS: he was emperor for fifty years. It pays to be your own best PR guy)

Austerity, modesty, restraint were all virtues equated with Romanness. Decadence, luxury and debauchery belonged to those furrin devils.

Cleopatra was a woman who ruled a country. She wore cosmetics and jewels. She costumed herself as a goddess, and draped ships with silk. She ate and drank the best of everything – and when Antony dared her to eat a "million-sesterce" meal, she made it happen low calorie style, by dissolving a rare pearl in vinegar and drinking it.

(apparently for this to actually work, you have to grind the pearl up into a powder first, which makes the story a bit more believable – cheers for that info, Chris Barnes!)

She represented female power, and basically she terrified the hell out of the Romans.

Cleopatra bore Julius Caesar's son, which wasn't relevant to anything dynastic, because the baby wasn't Roman. If you weren't Roman, you weren't anything. Caesarion was never going to ride into town and declare he was the rightful ruler of Rome. Citizenship of Rome required a local mother as well as a father.

If Octavia represented the ultimate Good Wife, then Cleopatra was the ultimate Bad Woman. She provided plenty of material for Octavian's anti-Antony propaganda, simply by being herself: the last of a long line of glamorous Egyptian pharoahs.

Better historians than I have written many more words on Cleopatra than I intend to today – besides, my theme is Roman women, not "kick ass female Pharoahs," so I'll concentrate on some of the ways in which Cleopatra's presence and public image affected Roman women. (For more on Cleopatra's fashions and the effect they had in Rome, check out this great post by historical novelist Stephanie Dray)

Augustus banned the worship of the goddess Isis, because she was so closely identified with Cleopatra. Banning a god was extremely rare in Ancient Rome, because they were so superstitious that they hated to offend any deity. Isis is a most excellent goddess, representing married women, queens, mothers and prostitutes all at the same time. While Augustus was often portrayed as akin to a god, he was very careful not to do the same with any prominent women of his family, in order to preserve a contrast between them and Cleopatra.

Augustus banned the worship of the goddess Isis, because she was so closely identified with Cleopatra. Banning a god was extremely rare in Ancient Rome, because they were so superstitious that they hated to offend any deity. Isis is a most excellent goddess, representing married women, queens, mothers and prostitutes all at the same time. While Augustus was often portrayed as akin to a god, he was very careful not to do the same with any prominent women of his family, in order to preserve a contrast between them and Cleopatra.

A statue of Cleopatra still stood in the forum of Julius Caesar, and now seemed tactless in the extreme. Augustus didn't remove the statue, but he did take the expensive pearl earrings from it, putting them instead on a statue of Venus. Only goddesses, not mortals, were fit to wear such finery. A subtle put-down, but a put-down nonetheless. No woman of Augustus' family wore jewellery in any official portraiture, while Cleopatra dripped gold and gems.

Octavia and many other women of the imperial family wore a particular hairstyle which we call the nodus style. It was a very harsh, pulled-back-over-scalp affair, with a tight bun of hair at the back, and a severe roll of hair on top of the scalp. This hairstyle represents the modesty and restraint that Augustus wanted the women of his family to demonstrate. Not a wisp of hair is allowed to soften the effect.

On at least one coin issue, Cleopatra chose this same hairstyle for herself, possibly in an attempt to promote herself as a woman demonstrating Roman (rather than those trashy Egyptian) values. Only, she added a couple of curls and a few accessories, because she didn't want to go out looking like a complete frump.

I love that about her. Woman had style.

=====

The Matrons of Awesome series was originally posted on Livejournal (LJ user: cassiphone) in March 2006 for Women's History Month.

The Matrons of Awesome series was originally posted on Livejournal (LJ user: cassiphone) in March 2006 for Women's History Month.

I'm reprinting the series as part of my Rock The Romanpunk week in celebration of my short story collection, Love and Romanpunk, which was published by Twelfth Planet Press earlier this year and is now available globally as an e-book as well as a pretty imperial purple print edition. Thanks to Wizard's Tower Bookstore you can also now purchase it for the Kindle.

Matrons of Awesome Part III – Republican Vixens

I'm sure you're good and sick of Roman matronal and maternal virtues by now, so let's have a bit of scandal and vice for balance.

wall painting from the House of the Mysteries, Pompeii

5. PompeiaPompeia was the second of Caesar's three wives, the first being Cornelia (a child bride, mother of his only legitimate child, Julia) and the last being Calpurnia (the one he cheated on with Cleopatra). Pompeia is memorable because she was married to Caesar during the first years of his career as pontifex maximus, high priest of Rome. It was a political marriage, she being the daughter of Pompey the Great, an ally and rival of Caesar's

(Pompey also married Caesar's daughter, which adds a whole layer of ick to the proceedings).

This is a story about the Bona Dea. Bona Dea means 'good goddess,' and she was a goddess without name or image. Men and women alike worshipped her, but there was one festival of the year which was restricted to women – or, to be specific, respectable married women (matronae). Every year, the wife of a public official would host the festival. All the men of the house would be turned out for the night (even male slaves were not allowed to remain) and the matronae of the city would come around.

No man knew what went on at this festival, though it was the subject of salacious speculation. Snakes were rumoured to be involved. The women – possibly – drank wine and called it 'milk' or 'honey'. Myrtle (the plant sacred to saucy goddess Venus) was banned from the house. Some years later, the poet Juvenal described the Bona Dea in his Satires as a psychotic orgy of madwomen, who tore around the city afterwards, pissing on statues and raping male slaves. Far too often, this is taken as historical fact rather than the "comedy" it was intended to be.

The point is that men were not allowed to know what went on at this festival, and (most) men respected that because the festival was an integral part of the Roman calendar. Romans were very superstitious about festivals and gods.

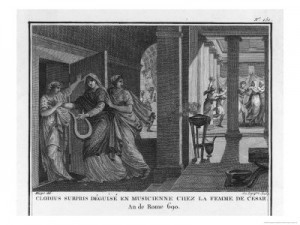

But one man – Publius Clodius, political hellraiser & troublemaker – risked the wrath of the goddess because he wanted to get into the knickers of Caesar's wife Pompeia, and she (as wife of the pontifex maximus) happened to be hosting the Bona Dea festival that year. So he disguised himself as a flute girl and crashed the party.

But one man – Publius Clodius, political hellraiser & troublemaker – risked the wrath of the goddess because he wanted to get into the knickers of Caesar's wife Pompeia, and she (as wife of the pontifex maximus) happened to be hosting the Bona Dea festival that year. So he disguised himself as a flute girl and crashed the party.

He never got near Pompeia. Her canny mother-in-law Aurelia (see previous post) spotted Clodius for a fraud a mile off. She and the Vestals covered up the sacred things, and they hauled Clodius out of there before he could say 'drag act.'

Here's the twist: the men of the city were furious, and tried to prosecute Clodius for sacrilege. The women of the city, however, refused to speak against him. This is particularly interesting because the Vestals were present, and they were the only women who had the same legal rights to testify as men. But the women were uninterested in the (politically driven) public vilification of Clodius. They simply said, "The Bona Dea will do as she pleases with him."

A few years later, Clodius was killed in a street riot, within sight of the shrine to the Bona Dea.

Caesar divorced Pompeia, though he stated publicly that she had not committed adultery, or in any way encouraged Clodius's advances. Why, then, sneered the other senators, was he divorcing her?

Because, said Caesar. Caesar's wife must be beyond reproach.

This isn't really a story about Pompeia. To be honest, we don't know much about her. But it is, very much, a story about Roman women.

6. Clodia

Another Roman woman synonymous with scandal was Clodia, sister of the aforementioned Publius Clodius. Clodia lived for scandal. She was rich, sexy and glamorous, and lived life to the absolute full. She belonged to a group of Bright Young Things who relished their decadent lifestyle. For a long time, she was the mistress of the poet Catullus, who immortalised her as Lesbia in poetry such as the following:

J.R. Vedzhelayn. "Lesbia"

VIVAMVS, mea Lesbia, atque amemus,(let us live, my Lesbia, and love)

rumoresque senum seueriorum

(and value all the rumours of old men)

omnes unius aestimemus assis.

(as worth a single penny)

soles occidere et redire possunt:

(the suns are able to fall and rise)

nobis cum semel occidit breuis lux,

(when that brief light has died for us)

nox est perpetua una dormienda.

(we must sleep a perpetual night)

da mi basia mille, deinde centum,

(give me a thousand kisses, then another hundred)

dein mille altera, dein secunda centum,

(then another thousand, then a second hundred)

deinde usque altera mille, deinde centum;

(then another thousand more, then another hundred)

dein, cum milia multa fecerimus,

(then, when we have so many thousands)

conturbabimus illa, ne sciamus,

(we will mix them all up, so as not to know)

aut ne quis malus inuidere possit,

(and so no one else will think ill of us because they know)

cum tantum sciat esse basiorum.

(how many kisses we have shared).

Lesbia and Her Sparrow, by Sir Edward John Poynter

In Dorothy L Sayers, there is a scene in which the newly married Lord Peter & Harriet Wimsey are basically making out against the side of the car – but this is only evident if you translate the Latin he is quoting (with many elipses to represent the smooching). The poet he is quoting is Catullus, and the poem is about "Lesbia."You can't believe how clever and educated I felt when I figured that one out.

After Clodia dumped Catullus (inspiring some far less romantic and more bitter poetry), Clodia moved on to another, younger lover. When he left her, she wanted her revenge and brought a court case against him for theft and other misdemeanors. The plan backfired, though, when her ex-toyboy hired Cicero, the best (and most moralistic) orator in Rome. Given that the Roman legal system revolved around who was the most persuasive speaker, Clodia was pretty much sunk.

Cicero destroyed Clodia in court, portraying her as an amoral slut in a speech that still exists today, full of quippy zingers that made the courtroom roar with laughter. By far the best insult he came up with was 'Clytemnestra of the Aventine' which, among other things, implies that she murdered her late husband. Clodia's social life may have revolved around scandal of the 'ooh, isn't she naughty' variety, but being exposed in such a public forum was beyond the pale. She found herself friendless and abandoned after the court case, and withdrew quietly from the social scene.

Semis, Asia Fulvia-Eumenea, head Fulvia, wife of Mark Antony, as winged Athena

7. Fulvia

Fulvia was another of the scandal-loving set that included siblings Clodius and Clodia, as well as the rather more famous Mark Antony. Indeed, Fulvia was married to Clodius before his violent death. After dabbling with another husband, she finally settled down with Antony, who was a political hothead and lover of luxury just like Clodius. Antony was a cannier politician than Clodius, however, and he was Julius Caesar's right hand man.

Fulvia was a loyal wife, and a mother of many children. When Antony went off to war, she went with him. Indeed, we believe that Fulvia is the first real woman whose portrait appeared on the coinage of Rome – all senators of Antony's military rank released their own coinage, and one of Antony's coins depicts a woman as the personification of Victory.

Of course, it could simply be the personification of Victory, but in Roman art personifications of virtues tend to have very bland, idealised faces (think the Statue of Liberty) and there's something about this particular Victory that looks very human. Given that Antony put a later wife on coins (though one more politically significant than Fulvia), it is likely that Fulvia is indeed the first Roman woman to appear on state coins.

When Julius Caesar died, Antony (who had perhaps expected to take over from his mentor as Dictator of Rome) found himself in opposition with Octavian, Caesar's great-nephew and heir. When Octavian and Antony were at odds, Octavian used propaganda to insult and degrade his rival, and Fulvia was one of the cards he used against him, referring to her less than pristine past, and calling her a 'virago.'

'Virago' means a violent or militant woman – in Roman terms, the absolute opposite of what a woman should be. This and other insults brought against Fulvia to discredit or mock her husband comprise most of the information we have about her, so she is generally remembered as a Bad rather than Good Roman woman.

But there's something very likeable about Fulvia – a feisty, aggressive woman who refused to kowtow to the Roman definition of the good wife who waits at home for her husband to return from war. Given that Antony had already caught the eye of Julius Caesar's exotic mistress, Cleopatra Queen of Egypt, one can hardly blame Fulvia for refusing to be the docile housefrau.

=====

The Matrons of Awesome series was originally posted on Livejournal (LJ user: cassiphone) in March 2006 for Women's History Month.

The Matrons of Awesome series was originally posted on Livejournal (LJ user: cassiphone) in March 2006 for Women's History Month.

I'm reprinting the series as part of my Rock The Romanpunk week in celebration of my short story collection, Love and Romanpunk, which was published by Twelfth Planet Press earlier this year and is now available globally as an e-book as well as a pretty imperial purple print edition. Thanks to Wizard's Tower Bookstore you can also now purchase it for the Kindle.

Love and Romanpunk is Kindled!

With much help from the generous and awesome Cheryl Morgan, Love and Romanpunk is now available in Kindle format as well as ePub! You can access it in shiny (well, matte) black and white at Cheryl's Wizard's Tower Bookstore.

With much help from the generous and awesome Cheryl Morgan, Love and Romanpunk is now available in Kindle format as well as ePub! You can access it in shiny (well, matte) black and white at Cheryl's Wizard's Tower Bookstore.

Fly, my pretty book, fly!

Matrons of Awesome Part II – The Republican Mothers

Angelika Kauffman, Cornelia Mother of the Gracchi, c. 1785

3. Cornelia Mother of the GracchiThere is a club of Roman mothers who are acclaimed for being strong, influential figures in their sons' lives. The more prominent a male citizen, the more likely it is that his mother will be praised for her virtues.

The interesting thing about Cornelia Mother of the Gracchi (always said like that, the entire phrase) is that, while she is primarily remembered for being the mother of famous Romans, they were not Roman heroes, nor people in a position to design their own propaganda. Her reputation as the ideal Roman mother was not, as with the mothers of Julius and Augustus Caesar, established to bolster the propaganda of her sons; if anything, their reputations are saved through an association with her.

The brothers Gracchi were political hotheads: Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus. They managed to get themselves killed in street riots, several years apart, due to revolutionary activities against the Republic.

Despite the less than heroic reputations of her sons, Cornelia's public image is set up as if they were princes. She is referred to by at least six of the major literary sources, always as an example of a great Roman matrona (married woman) and mother. To understand how impressive this is, you should know that references to non-imperial women in any Roman historical sources are scarce. Women are generally regarded as being irrelevant to politics and war, and almost all surviving historical texts about ancient Rome survived because they had to do with politics or war.

The Mother of the Gracchi:The Comic History of Rome, by Gilbert Abbott

Cornelia had a statue set up to her during the Republic, at a time when women had almost no public presence at all – unlike a dynastic form of government like a monarchy, a Republic can quite easily be run without involving women, and the Roman Republic very firmly kept women in the house, away from the Importandt Deeds of Men. Statues were politically relevant, so statues of women were almost non-existent.Here are some of the things that the literary sources tell us about Cornelia, the Ideal Roman Mother:

• She was chaste, and loyal to the memory of her dead husband, refusing an offer of marriage from Ptolemy, the King of Egypt. A univira (wife of only one husband) had a special sacred status among women in Rome, and Cornelia embodied this.

• She was intelligent and educated, and used these skills to educate her sons.

• She was tough with her sons, standing in for their father (who died young).

• She socialised with men on their own terms, hosting the Roman equivalent of literary salons (interesting considering the Lucretia 'ideal', no?) and was prized for her conversation in these spheres.

• She had enough political nous to learn from her eldest son's death; we have evidence of a letter she wrote to her younger son, warning of the danger he was in.

• Working in wool? Pfft.

I love Cornelia.

Ooh, and my favourite bit: motherhood was all-important to her. As you might have guessed by the 'refusing the King of Egypt' story, she wasn't interested in conspicuous wealth. It is for this reason that Cornelia continued to be held up as the feminine ideal long after her death, during the new puritanism brought in by the first emperor Augustus.

When a woman asked Cornelia where her jewels were (imagine a catty comment at a house party), Cornelia pointed to her children and said, "These are my jewels."

Yes, I named my daughter after her – Raeli for short. Aurelia is another mother in the style of Cornelia. Aristocratic, but modest. Widowed young, and refused to remarry. Tough, but fair. When her husband died, Aurelia was left with a bevy of daughters (well, two, but who doesn't love the word 'bevy'?) and one very talented son. She took responsibility for his education, and by all accounts was as strict as a father in discipline. Full credit is given to her as a parent that she raised Julius Caesar to be the man that he was.

Aurelia was a valued advisor to her son as he rose through the ranks (unlike the Gracchi, he did listen to his mother's advice). When he became pontifex maximus, high priest of Rome, he was given a house of his own and parental responsibility for the Vestal priestesses; he gave the running of this household over to his mother, not his wife.

Had Aurelia still been alive when Caesar brought Cleopatra home, she would have turfed the foreign wench out of Rome without breaking a fingernail.

I have a good story about Aurelia, but it will have to wait until Part III, because it properly belongs with an explanation about Pompeia, Caesar's second wife.

One last thing about Aurelia: though she was of noble blood, she married a younger brother and they found it difficult to make ends meet. So she ran an insula (like an apartment building) in the Subura, the roughest neighbourhood in Rome (and the one with the highest percentage of foreign immigrants), and she raised her family there. Considering that her husband (when still alive) was off on military service most of the time, it was an extraordinary lifestyle to choose, and shows that she was of stronger mettle than most aristocratic ladies.

Because he was raised in such an environment, Caesar is said to have spoken many languages, and been on friendly terms with people of all walks of life. This is why he was so beloved of "the people," not just his own class. His mother raised him to be a person first, and an aristocrat second.

Polly Walker as Atia, mother of Octavian, in HBO's ROME

ADDITIONAL 2011 COMMENTARY: I missed out Atia. I never even thought to include her, though she is briefly referred to at the beginning of this chapter. The simple truth is that I wasn't remotely interested in her, and had never read anything that sparked an interest in me. This was 2006, long before HBO's Rome, in which Polly Walker managed to channel Livia and Agrippina combined, and blasted everyone else off screen with her charisma. I'm now a fan, though in all fairness I would find it very hard to cover Atia's historical persona without the TV version deeply affecting me.Lindsay Duncan as Servilia in HBO's ROME

There is far less excuse for me missing out Servilia, mother of Brutus (the one who killed Caesar, not the one who pulled the knife out of Lucretia centuries earlier) whom I love deeply, but again I find it hard to extract her from a fictional version, in this case the portrait provided by Colleen McCullough in her Roman Masters series of books. Those books were responsible for my obsession with Roman history and to be honest my historical interpretations of Caesar and Aurelia will never escape her either. The Servilia (Lindsay Duncan) in HBO's Rome was marvellous, but in no way *my* Servilia – who would be played by Julia Sawahla. Sadly I'm pretty sure she hasn't been secretly filming scenes on and off since she was twelve, up to the age she is now. Why don't filmmakers think ahead?=====

The Matrons of Awesome series was originally posted on Livejournal (LJ user: cassiphone) in March 2006 for Women's History Month.

I'm reprinting the series as part of my Rock The Romanpunk week in celebration of my short story collection, Love and Romanpunk, which was published by Twelfth Planet Press earlier this year and is now available globally as an e-book as well as a pretty imperial purple print edition. Thanks to Wizard's Tower Bookstore you can also now purchase it for the Kindle.