Andrea Phillips's Blog, page 16

February 18, 2014

Apples, Oranges, and Author Earnings

I mentioned on Twitter last week that a recent update on Author Earnings comparing extrapolated Amazon data to Bookscan numbers is actively misleading. I thought it might bear unpacking that a little bit by way of analogy.

Imagine there is a grocery store selling both apples and oranges, and you need to figure out how many of each fruit is sold in a week (or at least which sells more than the other.) So you camp out in the store for an hour, and count how many of each fruit the customers buy.

You're probably going to get some useful information from that, to be sure -- whether the ratio between apples and oranges is roughly comparable, for example. You can even extrapolate from that hour -- multiply by how many hours the store is open, and you might get a ballpark number for how much fruit is sold. But that number risks being wildly inaccurate, because you're relying on that single sample hour to be perfectly typical. But a store has busy hours and slow hours -- some hours nobody's buying. Some hours, maybe someone's buying fruit for a world-record-size fruit salad. Some hours, you get a run of people allergic to citrus. All you can get is a very rough idea.

You can also ask a couple of orchard owners how much they get, look at the prices in circulars, and try to work out how much money the grocery store is making off fruit. But it would be a terrible mistake to try to, say, calculate the orchards' operating income from that loose guess of yours. The picture is a lot bigger than that one hour at one store, and is influenced by a lot of other factors.

Now let's say you get your hands on another source of information -- maybe the inventory records of a competing grocery store showing how many oranges it sold that same week. That's hard data, and it's great -- you can learn a little more about the size of the orange market in town from that.

But you can't then combine those two kinds of information as if they were the same to make conclusions about, say, whether Grocery Store A sells more oranges than Grocery Store B, and certainly not about whether Sunny Orange Productions is making more money than Crisp Apple Growers.

One of them is a cobbled-together piece of data and guesswork; one is hard data, but for only part of the equation. Each one of them tells some interesting stories, to be sure, but it's just as important to know what information the data can't tell you.

February 12, 2014

Self Publishing Pros & Cons

Yesterday, self-publishing wunderkind Hugh Howey launched a new site called Author Earnings, with a really fascinating report that suggests self-published authors earn as much as traditional publishers do -- in fact, his numbers suggest they earn more.

I have a few reservations about this data. For one thing, it leaves out other income streams available to traditionally published authors -- foreign rights sales, film sales, distribution on store shelves, and the like. I also find it extremely problematic to extrapolate actual dollar figures from Amazon rankings. One book might be at #2 selling 1500 copies in a day where the #1 is selling 1600. Or if there's a book that's selling 4000 copies, another selling 3800, another selling 3600, etc., those might be #12 and #13. Rankings are relative, not absolute, so the experience of a handful of books that hit the top of the charts simply can't give you a meaningful sales volume for other books at those ranks.

Related to that -- it's my experience that a book can float up to a higher rank on one good sales day, then sink like a stone. So extrapolating a full year of sales income based on a single Amazon sales rank is a very dicey proposition. Some of those books may have sold a hundred copies, and may never sell more than five in a day ever again; that doesn't mean those authors are guaranteed to make $10K for the year.

That said, these are problems with the methodology that would appear to affect both traditional and self-published books equally. What the data does show me isn't so much that self-publishing is a better bet, so much as that self-publishing isn't a bad bet. These books have an equal shot at the best-seller lists on Amazon. They move a comparable number of volumes. It may even be fair to assume the higher royalty figures on a self-published novel are enough to offset foreign rights sales and distribution on store shelves.

How, then, does an author decide what path to pursue? Let's take the issue of whether you can make comparable amounts of money off the table. What's left to think about?

Editing and Production. A good author-publisher is hiring an editor to help polish up the novel before it sees a reader. But a good traditional publisher is going to give you an editing pass to tighten up the story, and a separate copy-editing pass to fix the grammar, spelling and punctuation. Few author-publishers are hiring two separate editors, and while some talented editors have equal facility with macro- and microscopic issues, by no means do all of them. On the other hand, multiple passes over the same volume are a lot of work for the author. In my experience, doing a full review of multiple editing passes of the same book plus looking at your print galleys for any final changes is, eh, about as much work as producing an ebook your own self.

So in the end, the same amount of work is involved with both kinds of publishing. One has more eyes on the ball, and might produce a marginally higher-quality result, but if you hire a very skilled editor, you may well get the same result either way.

Promotion. This can have an enormous influence over the success of your book. It's nice to think that an excellent book will find an audience with or without promotion, but frankly this isn't true. The cream does not always rise on the internet; there's simply not enough room at the top, and too much stuff fighting for our attention.

Simply having a publisher carries some degree of promotion with it right away. Once you're on a publication schedule, you'll automatically get more interest from reviewers and inside-baseball readers. Word of mouth can spread from there; a traditionally published book starts with a leg up.

Self-published books are harder to promote, because not as many paths are open and you mostly have to go it alone. Many reviewers won't look at a self-pubbed book. Advertising is widely regarded as ineffective. Promoting by hanging out on forums and boards about self-publishing strikes me as trying to sell Avon at an Amway convention. If you have a great social media platform and the ear of a couple of bloggers, you can make some waves, but it takes a lot of hustle -- more hustle than many of us have in us. You can always hire a publicist, if you have the cash, but it's by no means certain that the book would earn enough to justify that expense.

Advantage: traditional publishing. More doors are open.

Awards Eligibility. ...And this is a stand-in for legitimacy as a whole. It's not clear how self-publishing affects your eligibility nor your odds of being nominated for major genre awards -- the Campbell, the Hugos. But I don't think it's doing anything good for your chances. And a million self-published volumes sold still won't get you into SFWA.

This is going to be a very personal element in the equation. Some of us couldn't care less about awards and organizations; we're in it for the readers, for the income stream, for the fun of it. But some of us crave these signifiers of accomplishment. How you come down on this one is entirely up to you.

Time and Flexibility. Traditional publishing is painfully slow. You're looking at several months to get an agent, several months to submit to publishers and get a contract, several months to get to publish. If you self-publish, you can get a book out there faster, see how readers respond to it, and take that into account as you're writing the next book. You don't suffer the risk of (for example) discovering that nobody wants a series only after you've completed the third volume, or the fifth.

And assuming that money is equal -- getting a book out sooner rather than later is a victory. If a book is going to sell five thousand copies the first year and two hundred a year every year after that, and you wait three years before publishing, you've lost six hundred sales.

Advantage: Self-publishing.

Investment and Return. One of the crazy scary things about self-publishing is that to produce a quality book, you have to invest some of your own money into it. You need a quality cover. You need a skilled editor. These things cost. If you're self-publishing, you're out of pocket for it. If you're traditionally published, not only does your publisher cover these costs, but they're also giving you an advance.

This means that you're guaranteed to make money on a traditionally published book. It's possible to actively lose money on a self-published work, if you put investment in it and it just doesn't sell.

This is another one of those very personal decisions. Are you comfortable betting your own money on your book? Then self-publishing is great for you. If not, traditional publishing might be a better fit. (Or if you have an existing audience, you might be able to crowdfund and mitigate those costs through what are essentially pre-sales.)

Availability. And here's the rub: these two publishing paths aren't going to be equally available to all authors for all books. Conventional wisdom is that a good book will always surface in the end, but we've all seen reports of authors who didn't get an agent or a contract until their second, third, fifth book... and then the earlier volumes sold gangbusters. Some writers never get representation at all, never strike an agent nor an editor the right way. Some of them probably give up. That doesn't mean they couldn't have found audiences if they'd gone it alone.

That gatekeeping function can serve as an important warning to you that your book is poorly written, trite, boring, or a half a dozen other kinds of terrible. Sometimes you're being rejected for a damn good reason. A lot of the time! And if your book is really bad, you don't want to hurry to put it in front of readers. Once burned with a bad book, they may not be inclined to try your next one. You only get one chance to make your reputation.

But if you want to publish with a traditional publisher, and you get a lot of nibbles but no flat-out bites... if you get the sense that you're almost there? Maybe it's time to shift gears. It's looking like it's by no means a career-killer to self-publish, not anymore.

There's not one true path at this point. There are clear advantages to both routes, and a lot of elements that come down to personal taste. You can relax and stop worrying about picking the wrong thing, I think; just make your decision and roll the dice. It's already a gamble anyway.

February 4, 2014

Writing a Serial: Cast Adrift in the Middle

As you may know, I'm in the middle of writing an e-published serial pirate adventure, The Daring Adventures of Captain Lucy Smokeheart. So far I've run a Kickstarter, written and released seven episodes, and been extremely forthcoming with my sales data. Now, though, I'd like to turn my attention to a more creamy and delicious topic: the process and craft of writing serial fiction.

You might think I'd start at the beginning, and talk about beginnings and outlining. But no, not today. I'm going to start out in the middle.

Not long ago, someone asked me if I've become tired of writing Lucy Smokeheart. It's a fair question. I work on most projects in one giant stretch -- novels and games alike -- and there comes a point where you find yourself utterly adrift. You've rowed out so far that you can't see the shore anymore, you definitely can't see the island you're aiming toward, and you can't be completely sure you're even going in the right direction anymore.

The middle is scary. You get to wondering how deep the ocean is under your boat and what lives there. You get to thinking about how nice it was before you started the journey, how much more picturesque the view was from the beach. You wonder if your destination is all that, anyway; the brochures always make these things sound better than they really are.

The middle is where a lot of writers give up on a book. The middle is squishy, it's nebulous, it's ill-defined; maddening in the utmost Lovecraftian sense. It's difficult, both emotionally and from a perspective of craft. It's where you start seeing the differences between your perfect vision and your imperfect execution. Doing anything else -- anything it all -- is easier than carrying on toward the end.

I'm outlining episode 8 of Lucy Smokeheart, so call me roughly 60% of the way through. If this disquiet were going to occur, it would've set in some tens of thousands of words ago. I think I can safely say that I'm through the middle and just about to the roaring wave that tumbles me to shore. And I think it's been so easy, I haven't grown tired at all, because I'm writing Lucy as a serial.

To be sure the series has had its share of difficult moments -- the insecurity, the inability to solve gnarly plot problems, and so on. I run into it... roughly in the middle of each episode, in fact. But since each episode is so relatively small, the middle is faster to row through. It's possible to grit my teeth and press through the agony in a couple of days, not over the course of weeks or months.

It's like the squishy middle part has been chopped into twelve equal pieces and apportioned between the episodes, and as a result each piece is much easier to work through. Writing one big work is an enormous bell curve, but writing a serial is a sine wave.

In terms of emotional difficulty -- if I may shift metaphors here -- it's the difference between climbing a mountain and taking a stroll through the hilly countryside. A serial is just plain easier to write.

We'll see how that holds through the end of the series, of course. There's still lots of time to get tired of pirates or lose my way. But I have a good feeling about this.

Lucy Smokeheart is on sale episode-by-episode exclusively on Amazon (and affiliate link ahoy); in omnibus editions on Barnes & Noble and iBooks; or you can buy a subscription including future episodes on Payhip!

January 28, 2014

Publishing On a Spectrum

Earlier this week, Chuck Wendig issued a call for self-publishers to put on their big kid underpants and approach the work of publishing in a polished and professional fashion. It's good advice, and comes out of a philosophy of respecting your audience and their time. You should all listen to Chuck. Dude knows what he's talking about.

It got me to thinking. Traditionally, we see self-publishing and traditional publishing as magnetic poles. Any given work can only be one or the other (or rarely, a work can switch from one to another) but you can't do both at the same time.

On the one side, a robust and time-proven machine polishes your book and sets it on shelves accessible to a wide readership; this is the path of gatekeeping, of minimum quality assured, of mainstream eyeballs and support from publicists.

On the other hand you have the scrappy lone writer-cum-businessman against the world. This is the path of exuberant creativity, of exploration, of unparalleled authorial control... but it can come at the cost of lowered quality and heightened obscurity.

Perhaps, I thought, there are more points along the spectrum than just these.

I'm a firm believer that a team makes creative work better. More eyes (if they're the right eyes) can help a work by spotting structural problems all the way down to fixing the typos. A skilled designer will make a better cover or website. There's a time for authorial vision, but there's also a time to shift your gaze away from the vision and onto what you've actually made, to see where it falls short.

So how might this work, then? How do you get the quality check and support network of traditional publishing and the freedom, speed, and lion's share of the profits you get out of self-publishing?

Some Potential ModelsThere are many ways that such a quasi-publishing group could work. I can think of three off the top of my head:

Writer's groups are the first obvious structure, and these occur informally already. Actually there are two separate kinds of writer's groups in existence -- on the one hand, you see writer's groups that help hone one anothers' work in private. On the other, you have loose collections of friends in and across genres promoting the work of other authors they like, admire, respect. (Probably some other reasons, too, because people are complicated.) I speculate some of these groups of friends will begin to cluster together and release all of their work under a single imprint -- a brand, if you will, that works the same way a publisher does in promising a certain minimum standard and style.

In this case, writers would continue to own all of their own work and wouldn't benefit from each others' successes; it's just a gentleman's agreement and breakable at any moment. This is probably happening already; I'd be genuinely surprised if it's not.

Co-ops with a buy-in that pool resources. Inspired by Adrian Hon's A History of the Future in 100 Objects -- and particularly the chapter on The Braid Collective. One of the problems with being a solo writer-publisher is that paying for pro-grade editing and cover services can be out of your range, especially if you're just starting out and not running on a trust fund. In this structure, the collective would give out from the kitty to fund promising books and help to get them done. In return, a small share of royalties would be paid to the collective from books launched with its help. (There could also be a small buy-in to the co-op, or a requirement to put in a certain amount of work before you can use group services, as with Critters.org -- to make sure that nobody exhausts the common pot without putting anything in.)

The problem with this structure, as Adrian points out, is that a breakout success of an author wouldn't need the group anymore, and loses the incentive to keep participating. The group functions as an accelerator for fledgling authors but there's not a lot of reason to stay on after you've achieved your own critical mass, nor is there a lot of reason to promote the work of others in the collective, beyond social reasons.

But still -- receiving editing and design services and support for maybe a 15% cut of your total sales on a single work isn't bad compared to what a traditional publisher keeps, huh?

Formalized groups with a partnership or corporate structure. In this case, a group of writers would team up to form what would amount to an actual publishing house for their sole benefit. The group would have veto power over any given work being released under the group label (though partners might be free to release as a solo work -- or they might not.) Every partner would receive a legally-binding share of profits from sales of every book the group releases, so every author would benefit from working hard to make every book thrive. Releases would be planned, staggered, and promoted heavily by all authors in the partnership. Groups like this would probably have more luck getting physical copies on store shelves and the like; there are probably other benefits to a corporate structure, too. Tens of thousands of corporate citizens can't be wrong!

There are probably other structures, too, but hey, this is just a thought experiment for now, hey?

Some ProblemsNaturally, there are a few obstacles between here and my socialist/capitalist publishing utopia. Here are the biggest hurdles these semi-pro-publishers would have to leap over:

Chemistry. It's difficult to keep the personal and professional separate when the professional is as personal as writing is. You can't put your heart on the line and expect it not to sting when somebody doesn't like what you've shown them. So: chemistry could be a problem for all three of these structures. Otherwise friendly writers don't always mesh together well in crit groups, sometimes because of matters of taste, sometimes because of personality, sometimes because of wildly differing expectations about responsibilities toward the group. If you've all cast your lot together, relatively minor personality conflicts could rapidly become a big, big deal.

Rules, rules, rules. What happens if one author wants to use the group to publish something the others find objectionable? What if they just think it's just garbage? What if just one person hates it? How is that conflict mediated, and what's the recourse? What if someone wants to join the group, or leave it? The rules for how such a group works would have to be very, very carefully thought through.

Tax structure. ...But I am not a lawyer. This is not legal advice. Let's just say there would be tax implications for each of these structures, and I don't know what they would be. They might be quite onerous. You'd want to have a nice chat with an accountant before trying to make any of these things happen.

Administration. In any given group, one or two people will probably get stuck with the scut work; that might just be setting times and locations for meetings for an informal group. For a more robust group that could be dealing with tax filings, distributing royalty moneys earned, manning a social media account, or minding an email inbox. A successful group could pay someone to handle these tasks, to be sure, but at least to begin with somebody's going to have to mind the store at the expense of their writing, and that could feel like a terrible sacrifice of one's career for the sake of someone else's.

I do think the rise of the author collective is just about on us; it seems like a natural, logical step for like-minded writers to work together for mutual benefit. It just remains to be seen what exactly that looks like.

And to think, publishing used to be a boring, staid business, too. We do live in interesting times, don't we?

January 22, 2014

Lucy in Cold, Hard Numbers: Part 3

This is a continuation of a series in which I share my sales numbers for the Kickstarted e-published serial pirate adventure, The Daring Adventures of Lucy Smokeheart. For earlier analysis, see Lucy in Cold, Hard Numbers: Part 1 and Part 2. Readers may also be interested in The Economics of Lucy Smokeheart, which laid out my budget for the project while the Kickstarter was running: Part 1 and Part 2.

There's a lot of talk going on in the social medias right now about author income. Publishing Perspectives released a pretty chart showing typical author income by type of publishing (aspiring, traditional, self-publishing, hybrid.) The data the chart is based on is from Digital Book World, and it shows about what I'd expect: writing books is a lousy way to make a living, and very few people do so.

Meanwhile, I've just released Prisoner's Dilemma, episode 7 of The Daring Adventures of Lucy Smokeheart, and I'm long overdue in reporting Lucy's sales numbers for the last few months. (For newcomers, I try to be as transparent as possible with numbers such as these to give other writers a clear-eyed view into one story, at least. Relevant background: the Kickstarter made $7701 from 251 backers back in March of 2013.)

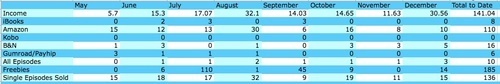

Here's the raw data to date.

The big conclusions: Since the Kickstarter ended and I began self-publishing the episodes, I've made $141.04 extra from Lucy to date (roughly -- this isn't excluding a small amount of transaction fees and some currency conversions may be off.) I've sold 136 individual episodes, 10 new subscriptions, and I've given away 185 episodes in all.

I'll also note that this includes 6 episodes over the course of 8 months; I'm releasing one new episode every five to six weeks, roughly, which is... meh, it's OK.

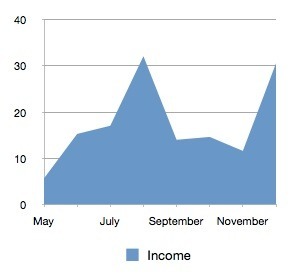

But let's see some of this in pretty chart format, shall we? Maybe we can pick out some interesting stories based on this data. Here's the first one: Income by month.

August and December have both been really great months for me, for a definition of "really great" that means "I earned enough to take the whole family to McDonald's one night."

This speaks directly to the heart of that debate about how much money a self-published author can or might be making. It's pretty clear Lucy Smokeheart isn't making me much of a living, and if I had a day job, I shouldn't be quitting it for this. It's also interesting that there just isn't a clear trend here, not up, not down. I have eight months of data and still not much idea what makes a good month and what doesn't.

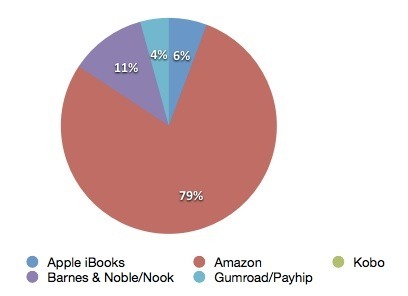

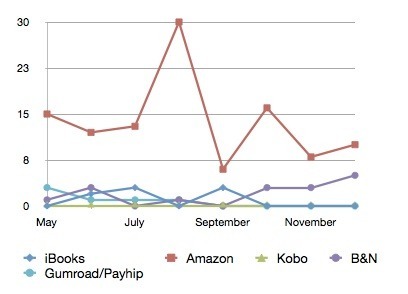

Then there's Sales by Retail Outlet.

No surprise here: Amazon is absolutely the gorilla in the room, followed by Barnes & Noble/Nook.

I sell copies on Apple/iTunes, but in a volume only marginally higher than episodes I sell directly through Payhip (or previously, Gumroad.)

In all of the time I have been collecting data, I have never once sold an episode of Lucy Smokeheart on Kobo. As far as I can tell, maintaining a presence on Kobo is pointless.

Then there's one that's a little bit of a mythbuster here: Sales vs. Freebies.

If you squint, it looks like there's a little bump the month after I've done a lot of giving away episodes, but a closer look at the data doesn't support that reading. The giveaways have all been episode 1, so further sales would be skewed toward later episodes. That hasn't happened.

So it may well be that freebies lead to sales... but that doesn't seem to be panning out particularly well for me. I dunno, maybe I'm doing it wrong. But the correlation of freebies=future sales just isn't there for me.

That said... I had the first episode of Lucy Smokeheart enrolled in KDP Select up until early September, and single-episode sales have been stagnant since then... mostly on Amazon. That leads me to speculate that dropping out of KDP Select has been bad news for Lucy Smokeheart overall.

See this last chart, Sales by Outlet per Month. It's true, Amazon hasn't been so good to me since I dropped out of KDP Select, though that's been disguised by a tiny picking-up of sales from B&N. And given the huge percentage of my sales are in fact on Amazon, I'm reconsidering that whole KDP thing again. At the very least, this is going to require some serious thought.

So in conclusion: This is what a successful Kickstarted ebook serial looks like once it makes it to the self-publishing phase. These are not impressive numbers. These aren't even fund-a-Starbucks-habit numbers. Of course my sales are skewed -- remember I have 248 subscribers getting every episode of Lucy Smokeheart as I write them, and they've already paid for those. (Plus another ten entitled to it... but they never filled out the backer survey.) I cannibalized my base of friends, family, and ardent supporters before I ever exported the first ebook.

But even so, man, it's a good thing this isn't my day job. ...Not that I have a day job...

And if you are so moved to support Lucy Smokeheart, there are manifold buying options online. Episode 1 is free! Or if you want to go big, can I interest you in a subscription to The Complete Adventures?

January 16, 2014

Haste and Legitimacy

So I have this novel called Revision about The Wiki Where Your Edits Come True. You may have seen me mention it before. It's a fun book, I think. Great characters, great concept, super-voicey. It's definitely not the train wreck that was my first novel (which is better not spoken of, trust me on this one).

So now there's the question of what to do with this novel.

I want to do it The Right Way, which means finding an agent, then finding a traditional publisher. And I want this a lot. I've wanted it since I was a kid. I want to be eligible for the Campbell (hey, a girl can dream, right? ...Assuming Lucy Smokeheart didn't start my clock already.) I want to qualify for SFWA. I want legitimacy in the eyes of my peer group.

This is what I've been trying (and completely failing) to do so far. I could keep trying -- I have by no means exhausted my options yet, in fact I've only just scratched the surface. But the road there is slow, so horribly slow. In a best-case scenario, running that gauntlet could take me two years. Or it could take four or more; figure one year to sign an agent, a year to shop the book around and get a contract, another two years to get a slot in the publisher's release schedule.

It could never happen at all. Two years could pass and you might find me exactly where I am right now.

That's a tremendous gamble with my career -- to burn that much time, potentially with nothing to show for it. Every month that passes is a month new readers could be finding me. A month I could be releasing more new work. A month I could be gaining inertia. Sure, I'd still be writing and building up a stockpile of unreleased material, but having a pile of manuscripts hiding in my pocket definitely isn't nearly as good as having 'em in front of readers.

And so the mind inevitably turns to other ways: self-publishing, Kickstarter, the startup indie publishing house. For me it's not about creative control at all -- I'd love to have a marketing team making decisions for me, a publicist supporting me, an editor telling me where I've been stupid so I can fix it. I prefer working with a team any day of the week. Hell, I can't even figure out what genre I write on my own!

Going these alternative routes is still a gamble, though. I might never be able to get a critical mass of readers, I might not be able to market effectively. I might be accidentally unleashing something horrible on the world and do irreparable damage to my reputation. And yeah, it kills my chances of all those shiny markers of legitimacy I want so terribly much.

But maybe it's the less risky path. I feel each tick of the clock in my bones, and I know I can't wait forever.

January 15, 2014

MlA97FbF2HwfB1M39rvm

January 10, 2014

What Happens When You Don't Like a Friend's Work?

Over the years, I've become twitterfriends with quite a lot of writers: SF/F writers, games writers, transmedia writers, bloggers, and on and on. They are to a one funny, clever, insightful people. (Then again, if they weren't I wouldn't be following 'em, so there's that.) One of my ambitions for this year is to do a lot more reading, particularly the work of all these people that I love and respect from social media.

Which raises an interesting question: what happens if I read something written by someone I really, really like... and I really, really don't like it?* And of course there's the flip side of that: what if someone I'm friends with really, really doesn't like my work?

Various writers have talked about whether or not they should ever write negative reviews of another writer's work. These are often couched in terms of reputation and career -- negative reviews might rob you of a valuable connection, negative reviews might rob the reviewee of potential sales, etc. etc.

But there's not a whole ton of attention paid to what I think is a deeper underlying issue. Genre fiction, in particular, is a fairly small community of creators. Many -- maybe most! -- of that peer group are friends, or at least friendly. So in a negative-review situation, the problem isn't just one of what's best for your career. Often the question is how to manage a potential source of conflict and tension in your relationship with somebody you really like a lot.

Even aside from outright reviews, if you simply talk a lot to another writer and find their work not to your taste, poorly executed, or otherwise lacking, do you tell them? Do you just keep quiet and hope it never comes up? Do you cherry-pick one thing you kinda liked and talk it up?

Whether to be open and honest about the not-liking is going to heavily depend on the nature of the relationship. In general the closer you are, the more honest you can be; there's not much point in going out of your way to tell a nodding acquaintance that their latest book just didn't rev your engine, or you think they must have been drunk on bathtub gin and battery acid to write so poorly.

In a closer or warmer friendship, it can be a lot trickier, to be honest. There's no one right way to handle it, because human beings aren't a one-size-fits-all kind of deal.

But one thing is absolutely clear: if you find you dislike something created by someone you really like, it's important to remember that taste varies. It's easy to fall into the trap of thinking that if you don't like something, it is unlikeable. That if you don't care for the writing or the characters or the plotting or the worldbuilding, it's because the writing is actively and objectively bad.

This is not the case. Let's say that again: Taste varies.

For my part, I'm totally fine when friends don't like something I've done; I've never thought I'd receive universal love and acclaim to begin with. My writing isn't perfect, nor will it ever be. And even if I were to execute perfectly on my vision, eh, different people enjoy different things. Sometimes, what I'm putting out there just isn't what someone else wants to pick up. And that's not just OK, it's to be expected!

A healthy separation between the creator and the creation is always, always important -- especially for the creator. It's tragically easy to feel like the way that someone reacts to your writing is a referendum on your worth as a human being.

But the fact is that no writer, no artist, has universal appeal. Taste varies, perception of quality even varies, and that's cool. We can all still be friends.

* ...And to all of my suddenly worried and more than slightly neurotic writer friends, I really, REALLY promise this isn't about you. It's not about anyone in particular. Relax, we're cool.

January 8, 2014

Star Wars and Continuity

Now that Disney owns Lucasfilm, we've been seeing epochal shifts in how the Star Wars property is handled. JJ Abrams is directing a new film. Two Star Wars games in development were canceled and Lucasarts was shut down entirely. And now, Marvel (another Disney property) will be reclaiming the license for Star Wars comic books from Dark Horse in 2015.

Now, Star Wars canon and continuity has long existed in a curious state, where the films and TV series were the Bible and all other works were apocrypha of dubious "truth." Given the many changes underway, fans are speculating on how continuity will be handled by Disney going forward.

There's a fair amount of enthusiasm for the idea of bringing the entire Extended Universe into legit-canon status, working through and retconning whatever conflicts there are, and in general shaping the sprawling, messy story world that is Star Wars into a strict and rigorous history, where we know what's factual and what is not.

I'd like to argue against this.

In transmedia narrative, we often talk about showing what happens elsewhere once a character walks off the screen (or the page.) In that traditional model, we might see the burning of the Skywalker farm in Episode IV, for example, or Palpatine's behind-the-scenes political machinations.

But this is not the only way to do storyworld or continuity. History itself does not have the rigor we demand from our fiction. In reality, sometimes all we have are biased accounts, sometimes conflicting witness reports, records that may be inaccurate, misleading, second-hand. And mixed in with our history we have myth. Was there a King Arthur in England, or a Robin Hood? Maybe, maybe not. We don't really know.

Star Wars should be like this. We should accept that such an intricate world with so many creators involved will have inconsistencies, and write up such conflicts as the result of bias and the messy process of time. It all happened a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, after all. Who are we to know the ultimate truth?

Now, I recognize I'm voicing a minority opinion, here. Fandoms do tend to love clarity, knowing exactly what happened, so they can draw connections and make conclusions all on their own. Ambiguity is aesthetically displeasing to many of us.

But I think there's a certain beauty in having a messy storyworld, one where myth and fact blur together. And in demanding a concrete truth from a universe like Star Wars, we are robbing ourselves of potentially amazing stories.

Imagine, if you will, the manifold ways that the relationship between Princess Leia Organa and Han Solo could play out. In one they marry and have twin babies, as in the books. In another, she lays down her life to save him and he spends the rest of his days hunting for vengeance. In still another, a woman from Han's past comes between them, and decades pass before that wound can heal.

We don't need to know which one is "true." Marvel should know that -- how many reboots and alt-worlds have we seen in comics, after all? Perfect consistency doesn't really matter, shouldn't matter at all, provided what we get out of the bargain are rich, deep stories. Why close the door on them before they've even been told?

January 7, 2014

Announcing The Walk Game

You know what I haven't done in a while? A proper project launch announcement. But GET READY, because this one is awesome.

I'd like to (somewhat belatedly) announce I was involved in a game called The Walk, a fitness game along the general lines of Zombies, Run! --Which should be no surprise, because as with that game, it's a production of Naomi Alderman and Six to Start. Here's a description from the press kit:

The Walk is a smartphone fitness game and audio adventure released on 11 December 2013. It combines exciting gameplay with a high-octane thriller story, encouraging players to walk more every day. When you're playing The Walk, every single step counts in a journey that will save the world.

...

The Walk begins in Inverness station. Through a case of mistaken identity, you the player are given a vital package which must be couriered to Edinburgh, but as you're about to board the train, terrorists blow it up and set off an electromagnetic pulse! None of the cars or trains are working - you'll have to walk - but now the terrorists are on your trail because they want the device you're carrying, and the police are after you as a suspect in the bombing. To survive, you'll have to join up with other escapers from the city - but how many of them can you trust, and are they really who they say?

I am stupendously proud of the work that I did on this game (and in fact that the whole team did.) And I'd like to share a little bit of behind-the-scenes on The Walk, the production process, and various things that influenced me during writing.

What Did You Do, Andrea?My credits are a little clunky; they read "Storylining, character creation, early drafts and additional writing." So what does this mean, exactly?

The process of writing the game was like this: Naomi Alderman and Adrian Hon came to me with a general seed for a story. Some things were clear from the beginning: it would be a walk beginning in Inverness; there had to be a reason you had to walk rather than taking any automotive transportation. We threw around a lot of ideas (fuel-eating nanobots!) and ultimately settled on an EMP blast that's disabled meaningful mechanized transportation.

Then Naomi and I talked generally about characters and overarching plot, and she set me free to write the first draft of about a dozen initial scripts. After I delivered that first draft, she went in and did a revising pass in which she changed almost every single word (literally!)

...Which sounds horrible, but I promise you wasn't at all. Most of the heavy lifting I did was preserved; the characters are roughly the same, the shape of the plot is the same; Naomi fine-tuned to add in additional depth and emotion, to revoice for authentic Britishism, turn some dials up to eleven, and so on. Her mid-season finale is soooo much better than as originally written, I can't even tell you. The combined result is, in her words, finely layered like a croissant, a blending of our talents that is arguably much better than either of us might've done on our own.

Naomi and I, we're a great team, is what I'm saying.

The rest of the scripts worked mostly the same way, except that the absolutely amazing Bex Levine stepped in to break story with me for the scripts on a scene-by-scene basis. She is brilliant and absurdly good at this, and I wish I could keep her to help me outline everything ever from now on. Also, I've become an evangelist convert to outlining; the scripts that were written from this tight outline were so much easier to write. (And indeed, I prefer writing in this kind of team-based collaborative environment, as well; I wish I could work with other talented writers on everything ever.)

Finally, I wrote a few of the extra pieces of story you can find along your journey -- the odd newspaper clipping or postcard. No surprise, this kind of storytelling-through-documentation is always one of my most favorite things.

So basically: I did a lot of writing but I wasn't a solo writer. Whew!

Living in an EMPThey say you should write what you know. In high school, I went to Scotland with friends for a week one fine April, and actually did a lot of walking through the countryside. (Freezing my tail off and listening to Pretty Hate Machine on repeat, as a matter of fact.) Alas it was not as thrilling as The Walk needed to be -- you can only make so many jokes about fields of sheep watching you pass by. Clearly my personal experience wasn't going to cut it.

So in the run-up to initial writing for The Walk, I did a lot of thinking about what it would be like to live through an EMP blast zone, and working through the logic. Some older cars would work, to be sure, but the roads would be clogged with electronics-driven cars stopped wherever they were when the pulse hit. Some electronics might be shielded, somehow -- cell phones, cameras, radios -- but a lot of the infrastructure to run them might be functionally dead: cell phone towers, radio stations, power plants and substations.

And then I had an experience uncomfortably close to what I'd been writing -- my delivery of the first batch of scripts for The Walk was cut short by Hurricane Sandy. Suddenly I got to see exactly what it was like when a major urban region didn't have power; we were out for nearly two weeks in my town.

As a result, I think the later scripts are richer in lived-experience-of-power-loss. I suddenly knew what it felt like to be cut off from the world, how lonely and isolated that feels. How local communities banded together for mutual good. How hard it is to do simple things you take for granted -- showering, washing dishes. That modern gas pumps need electricity to operate even if you could find a working car. How generators fail horrifyingly often, and how short a battery life seems when it's all you have. What happens when calling an ambulance or police for help isn't an option anymore.

And that wasn't even an EMP.

I like to think this experience adds quite a lot to The Walk, especially as the season goes on and the impact of the EMP really sets in.

In ConclusionIn the coming weeks, I'm planning on playing through The Walk myself with fresh ears. I've only just heard the first couple of episodes -- I have a lot of trouble listening to recordings of things I've worked on, performers making the story come to life makes me weirdly emotional and weepy.

I'd really love to hear what you think about The Walk, too. It's always a joy to see when an audience picks up on something small you put in, and an even bigger joy when they find things you didn't even know you'd left there. And... hey, I hope you love it.