P.C. Zick's Blog, page 2

June 17, 2025

THE HUMAN HEIRS OF MARJORIE KINNAN RAWLINGS

Last week, I wrote about the inspiration of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings on my life and career. Here is the essay “Human Heirs” that I wrote for the Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Essay Contest in 2001 as I left my decades-long teaching career to venture into freelance writing. The essay won first place and set me on the journey of a writer for the next twenty-four years.

Human HeirsMy new world frightened me. I didn’t see the beauty of the live oak trees draped in moss or understand the lure of frogs singing on a summer night. The wildlife of northern Florida held threats to my safety and left me wondering why we had moved here from Michigan.

I saw danger lurking in the surrounding wilderness. One morning I looked in the mirror and saw a tick, fat with my blood, attached to the center of my forehead. The first time I saw a broadhead skink, I threatened to leave my new home and head back to a land of lizard-less landscapes.

After hearing I wanted to leave, a neighbor suggested I read Cross Creek. I had never heard of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings even though The Yearling sounded familiar.

Not only was Ms. Rawlings a writer, something I aspired to be, but she had conquered her fears of a Florida wilderness and wrote with affection about an area much more rural than anything I had experienced. For the first time, I began to understand the rhythms of life in this land that was beginning to own me.

When I heard the call of my first “chuck will’s widow” heralding spring, I welcomed the songbird with pride because, thanks to Ms. Rawlings, I knew it was a cousin of the whip-poor-will. Now I listen for it every year.

I read about her trip to the Everglades with Ross Allen to hunt rattlesnakes. This woman became my hero as I fought to overcome my fear of snakes. When I welcomed a black racer into my garden last year, my appreciation for the nature of north Florida became complete. I had not made a mistake by moving here.

I devoured her novels. Jody Baxter’s struggles chronicled a rite of passage much purer than anything I’d read before. And South Moon Under allowed a glimpse into the people I had begun to call neighbors.

The picture of Ms. Rawlings, on her porch with the typewriter in front of her, remained a constant in my mind as I struggled to find the writer in me. That picture became reality when I began to put aside the distractions of my life as a teacher and started my own journey as a writer.

Recently one of my students struggled to find an American author to read. I suggested South Moon Under. When he finished, he said, “I never thought I’d like this book, but I want to thank you for suggesting it. It is the most interesting book I’ve ever read.”

No longer afraid of the world around me, I returned what had been given to me when my neighbor suggested I read Cross Creek. Ms. Rawlings lives on in those “human heirs” who sojourn here for only a short time while the creatures and landscapes around us continue their cycle of life and death and rebirth, completing the essential rhythms of a world filled with wonder.

****

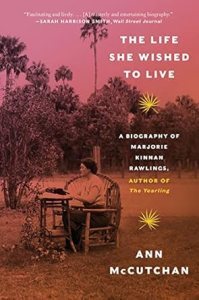

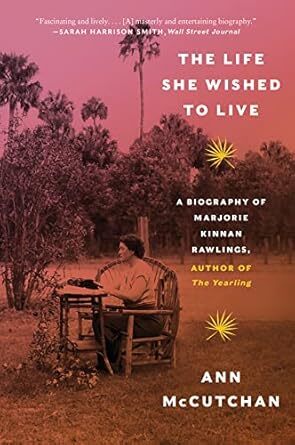

I am in the process of reading Ann McCutchan’s biography of Rawlings, and I am struck by the honest assessment of herself and her shortcomings in her letters. I’m not only learning about her, but her truths are teaching me about myself as well. The Life She Wished to Live is an astounding work of nonfiction that delves into the creative mind. Rawlings’s editor, Maxwell Perkins, also was editor to Ernest Hemingway, Scott Fitzgerald, and Thomas Wolfe–just a few of the brightest and best authors of this era. I highly recommend the book for its historical perspective, including a perspective on women journalists of the early twentieth century.

Purchase on Amazon

Purchase on AmazonI’ll leave you with the quote from Cross Creek that inspired the title of my essay and provided me with a road map for its theme.

“Who owns Cross Creek? The red-birds, I think more than I, for they will have their nests even in the face of delinquent mortgages. And after I am dead, who am childless, the human ownership of grove and field and hammock is hypothetical. But a long line of red-birdsand whippoorwills and blue-jays and ground doves will descend from the present owners of nests in the orange trees, and their claim will be less subject to dispute than that of any human heirs.” Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, Cross Creek, 1942

June 10, 2025

A WRITER’S LIFE AND INSPIRATION

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, author of The Yearling and Cross Creek and many more books, remains an inspiration to me even though she died a year before I was born. Still, her journey as author and woman who left the north for the south provided a road map for me. I am one of her “human heirs” she writes about in Cross Creek, although she believed the true heirs that owned the land were the beautiful creatures living in nature.

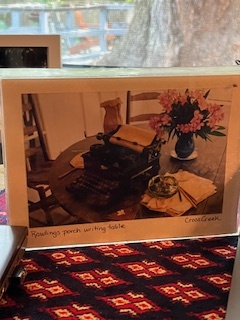

Photo: Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings at her desk on her porch at Cross Creek.

I held a vision of myself as a writer for years. I pictured myself sitting hunched over a manual typewriter, cigarette in my mouth, whiskey glass on the table next to me, words flowing onto the paper. That image remained with me even though I quit smoking and discovered that whiskey fed a hangover, not the muse. And the image remained even though the typewriter of my fantasies sits only in museums.

The image of the manual typewriter has remained with me for three decades. When I first visited Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings home in Cross Creek, Florida, on the screened porch of the preserved home, now a state park, the sight of the manual typewriter where she wrote her most famous books jumped out at me. My vision come to life.

To this day, I keep a postcard photo of her table/desk on my own desk to remind me that I am a writer.

Several years ago, on yet another visit to her home, I did something I’d never done before. I ventured out onto the actual Creek in my kayak.

Photo: The postcard I keep framed on my desk still inspires me.

Mostly my husband and I paddled in silence in awe of the drooping live oaks with branches free from leaves but not the Spanish moss which gives rural north Florida its special charm even in the dead of winter. But still flowers bloomed on the banks, birds flew and fed nearby, and fishermen in simple boats lazily floated on the crossroad between two large lakes, Lochloosa and Orange.

It felt at home as if I’d paddled this water my whole life.

Perhaps the connection I felt cemented itself into my consciousness back in early 2001 when I contemplated leaving my teaching career to write full-time. As I made the decision, I entered a Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings essay contest. The same week I left the classroom for good, I received word I had won first place and received a $500 check for the honor.

That check represented the most money I had ever made for one short piece of writing so far in my short career. It represented all the confirmation I needed to know I had made the right decision.

More than twenty years later, I am even more convinced that the spirit of Ms. Rawlings and her work gave me the inspiration and courage to step out into the world.

Next week – The Human Heirs of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings – the essay that changed my life.

In the meantime, check out the most recent biography of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, The Life She Wished to Live by Ann McCutchan.

My daughter who is well aware of my fondness for the author gave me the book. It’s the most comprehensive book I’ve ever read about the woman who made Cross Creek famous.

As I read it, I am struck by her independence, fierceness, and dedication to her craft.

On amazonJune 3, 2025

LIGHTHOUSE PASSION SERIES – CEDAR KEY

Perched atop one of the highest points on Florida’s west coast sits the state’s shortest lighthouse. The Cedar Keys Lighthouse, built in 1854, stands a mere 28-feet tall upon a 52-foot sand dune on Seahorse Key in the Cedar Keys National Wildlife Refuge in the Big Bend area of Florida.

I’ve visited Seahorse Key several times over the years. It’s closed for most of the year to visitors because the island is host to breeding spots. The trees at the edge of the water are filled with pelicans–many of them white pelicans.

When open, I’ve also visited the lighthouse. The most strenuous climb are the steps heading up to the top of the sand dune where the lighthouse sits.

In the 1800s, Cedar Key became a prosperous shipping port. Seahorse Key, sitting in the middle of the estuaries of the Suwannee and Waccasassa rivers, was deemed to the be ideal spot for marking the entrance to the Suwannee River. So, Lt. George Meade designed and built the lighthouse. The iron and steel structure cost only $12,000 to build.

Even the Hurricane of 1896 did not harm the lighthouse even though it destroyed a pencil factory on Atsena Otie Key within sight of the town of Cedar Key, which was also impacted severely by this harsh storm.

Seahorse Key lies three miles out in the Gulf of Mexico from the dock at Cedar Key and is only accessible by boat. It is managed by the Lower Suwannee National Wildlife Refuge but the University of Florida leases three acres of the island that surrounds the lighthouse. In 1952, the University of Florida established its marine laboratory on Seahorse Key. The keeper’s quarters on either side of the short tower have been turned into dormitories for UF students; however, the marine lab has been closed since 2024 because of damage caused from Hurricane Helene.

When the area isn’t recovering from hurricane damage, visitors are only allowed at the lighthouse two times a year. Several different tour companies offer shuttles (for a fee) during the open houses. Visit the Cedar Key Chamber of Commerce’s website for more information on when the lighthouse might once again open for visitors.

May 27, 2025

SMALL TOWNS ROCK – CEDAR KEY, FLORIDA

When I moved to a small north Florida town in 1980, I loved the location in the middle of the state. We could drive to the Atlantic Ocean in less than two hours, or we could be sitting at a bar overlooking the Gulf of Mexico in less than ninety minutes.

Harry Cruise, a Florida author from Gainesville, wrote about this phenomenon in an essay in his book Florida Frenzy. Cruise, from south Georgia, eventually took up residence in Gainesville, Florida, where he taught creative writing at the University of Florida.

“I can leave the place where I live [Gainesville] a couple of hours before daylight and be on a deserted little strip of sand call Crescent Beach…while the sun lifts out of the Atlantic Ocean…I can leave the beach and in three hours be out on the end of a dock, sitting in the Captain’s Table [a Cedar Key institution until destroyed by a hurricane]…while the sun I saw lift out of the Atlantic that morning sinks into the warm, waveless Gulf of Mexico. It makes a hell of a day.”

I fell in love with the sleepy fishing village of Cedar Key on my first visit there more than forty years ago. Many years, I requested a trip there to celebrate my birthday. Dock Street sits right on the Gulf of Mexico and hosts most of the town’s bars, restaurants, and shops. Two blocks over, 2nd Street serves as the village’s main street. The Island Hotel Restaurant is housed in one of the oldest structures on the key. Built in 1859, it was constructed to last even when the Union Army invaded and destroyed much of the town.

[image error]Cedar Key, with its deep harbor and lush trees and abundant seafood stood on the cusp of becoming one of Florida’s most important ports by the mid-1800s. It became a major shipping port for lumber and oysters. And the various keys were mined for their abundance of cedar trees to make pencils.

Several events—manmade and natural—kept it from becoming the “Tampa” of the Sunshine State. First, during the Civil War the Union soldiers burned everything they could because the port was seen as strategic for the Confederate Army including the first Atlantic to Gulf railroad, which had been completed in 1861. It started in Fernandina Beach north of Jacksonville and meandered southwest to Cedar Key.

After the war ended, the town began to revive itself minus a railroad terminus. However, steamships came in and out of the port. When Henry Plant tried to bring the cross Florida rail line back during the Gilded Age, he found resistance with the residents of Cedar Key. And the coveted cedar trees had not been replanted, which depleted the one source that had kept the town going even after the railroad was gone. Then a major hurricane in 1896 destroyed the village once again, and changed the destiny of the western coast of Florida. Plant moved south to Tampa and set up shop.

Today, the village of Cedar Key is a fishing village and an artist colony with those in the know making it their destination for getaways. I finished my novel Tortoise Stew in a friend’s cottage on one of the bayous off State Road 24, which ends at the corner of Dock Street and the Gulf of Mexico.

Hurricanes have attempted to destroy Cedar Key over the years, most recently in 2023 and 2024, but the spirit of the village and its residents is resilient. And it’s a place where no one is a stranger for long. Recently, two teenage girls lost their way on paddle boards. They washed up on one of the outer keys but weren’t found until the next day. I watched the rescue efforts via social media. Folks came with their boats from miles around to assist in the rescue. Fortunately, the two were found the next morning sheltering in place and shivering until the warmth of the residents enveloped them and brought them back to safety.

Its quiet and simple nature may not be for everyone. But it suits me. If I want noise and constant motion and crowded streets, I can always head south.

Next week, I’ll come back to Cedar Key to explore the unique lighthouse that sits three miles into the Gulf on Seahorse Key. In the meantime, visit the Cedar Key Chamber of Commerce’s website, to learn about the village’s art galleries, community garden, museums, marina, and accommodations.

I wrote Tortoise Stew, the first book in my Florida fiction series, while looking out over the bayous off Cedar Key, Florida. The setting served me well as I wrote about wildlife–both human and animal–that create the wackiness that is the Sunshine State. A recent reader wrote to tell me, “I really enjoyed Tortoise Stew and rate it with the books I have read by [Carl] Hiassen.“

Grab your copy of tortoise StewMay 20, 2025

CAN’T SEE THE FOREST FOR THE JUNK MAIL

I no longer receive many personal items in the mail. I still send out cards and letters myself, despite knowing I’m in a slim majority. I send photos, fun pop-up cards, and feel-good notes of encouragement. Soon, I will be an anachronism. Recently, I had to buy stamps on a Sunday and couldn’t wait for the post office to open or for stamps to be mailed to me. So, I went to two different places and asked about stamps. I received blank stares from behind the counter. At the last place I tried—an office supply store—the manager overheard as I was explaining what a postage stamp was. He quietly directed the young employee to a drawer where rolls of stamps were kept. The kid shrugged and told me he had no idea such a thing even existed. Sigh. Perhaps I am already an anachronism.

I use the USPS to send things of meaning in small envelopes. And in return, my mailbox is stuffed full of junk mail. I find it most annoying that the majority comes from organizations devoted to helping humanity and the environment. Many of them, I send donations to help them with their efforts. And almost immediately in response, I receive junk mail requesting more money.

Three months ago, I decided to stockpile the junk mail, and the result shocked me. I had to take action before the envelopes filled with multiple sheets of paper and “gifts” required a move from my office space.

I organized the ungainly pile and wrote individual messages via websites or emails—not letters—to each of the most offensive nonprofits to protest and to request they no longer send me anything in snail mail.

Eight of the fifteen organizations that I contacted responded via email. Only one addressed the issue of conservation. The rest said I had been removed from their mailing lists but warned it could take up to two months for the snail mail to stop with no mention of my concerns about the environment.

The Sierra Club, one of the junk mail offenders, published an article in 2019 with the following information on junk mail.

“According to the Center for Development of Recycling at San Jose State University, an American adult receives 41 pounds of junk mail a year. To produce this much paper requires cutting down somewhere between 80 million and 100 million trees annually. If left standing, these trees would absorb 1.7 million tons of CO2 a year.

The World Wildlife Fund reports that over 40 percent of all industrial wood is turned into a paper product, making paper production the second-largest use of logged wood after building materials.”

Click here to see article in its entirety.

After making my donation to the Sierra Club for 2025, I received six pieces of junk mail from February to May. Their response said they didn’t respond to individual emails, so I would have to create an account and then make my request that way. I did so but have received nothing in response.

The World Wildlife Fund did respond.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://pczick.com/wp-content/uploads..." data-large-file="https://pczick.com/wp-content/uploads..." src="https://pczick.com/wp-content/uploads..." alt="" class="wp-image-105388 size-full" />“Thank you for your feedback regarding our mailings and we apologize for any inconvenience they may have caused. We are always happy to edit any donor’s mailing preferences at any time, and we have various options to suit different needs. We receive a great number of donations via mail in response to our mailings which reach a broad demographic of donors who we may not be able to reach otherwise. While physical mailings may not be the best option for everyone, they have proven to be very effective tools for our fundraising efforts. The cost of the mailings is very low relative to the dramatic benefits of using them to get WWF’s message across to a larger portion of the population. Rest assured that we take our environmental stewardship seriously, and that all of our mailings are printed on 30% or greater post-consumer recycled and Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certified paper.”

I will still send my personal mail, but I know I risk the possibility that when I open my mailbox, it will be empty. I can only hope. And maybe when I do receive the infrequent card or note, it won’t get lost amongst the junk.

May 13, 2025

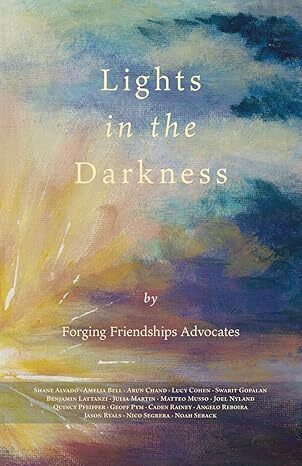

Lights in the Darkness

I recently spent an unforgettable afternoon at a book reading for Lights in the Darkness, a book of essays from sixteen nonspeaking authors. Listening to the words from the minds of these young people who could finally be heard after years of not being able to communicate moved me to tears and opened a whole new world of understanding for me.

The essays give a view into the thoughts of these nonspeakers who have become “spellers” to communicate. The authors are creative, intelligent, and profoundly compassionate. And their stories brought me to a greater understanding of close family members who are neurodivergent and struggle to communicate.

It is a universal need to be seen and to be heard. True communication requires listening, watching, and understanding. If someone doesn’t communicate with the standards within our society, often we make assumptions about intelligence and abilities instead of recognizing that some brains work differently from the standards of the average neurotypical person. The neurodivergent person’s brain simply works another way.

Close your eyes and imagine what it would be like to be the one who is ignored and shoved aside because someone else has decided who you are. Or imagine how you felt when it happened in your life. It feels pretty lousy.

For anyone whose brain functions at different levels from what is considered the standard, the ability to communicate thoughts and emotions so others understand them is probably the hardest challenge. And it is only amplified a thousand times more for those who are nonspeakers.

Until recently, nonspeakers were discarded and ignored, except by those closest to them who knew the truth. The thoughts within those brains were universal, but those same brains don’t allow the words to come from their mouths. Those same brains sometimes cause their bodies to do things out of their control, so it makes them seem something other than what they were—just regular folks who feel pain, frustration, joy, and love.

Do not listen to those who “think” they know something about neurodivergent individuals but don’t know the individuals or follow the science. Those on the spectrum face challenges that I don’t, but it doesn’t make them less than anyone. They write poems, they pay taxes, and they are potty trained—all things one man who should know better has said they can’t do. He is the one who is less than when he diminishes other human beings.

And read Lights in the Darkness to really understand that human emotions are universal even if we have different ways of expressing them.

LIGHTS IN THE DARKNESS ON AMAZONMay 6, 2025

LIGHTHOUSE PASSION SERIES – ST. AUGUSTINE

Whenever I mention the lighthouse in St. Augustine, Florida, on Anastasia Island, I know immediately if that person has been there. Gasps of “Now that’s a climb” or some variation usually occur. The 209 steps appear daunting, and it can seem as if the winding spiral staircase is never going to end , but suddenly it does, and the 165-foot climb is all but forgotten. It’s a little bit like giving birth. It’s labor intensive getting to the top, but once there and walking around 360-degree balcony, the climb is all but forgotten.

Its black and white striped spiral column topped by the light itself wrapped in red can be seen from land and water for miles. The chosen spot on the north end of the island near an inlet was originally chosen by the Spanish in the 16th century. They built a watchtower to keep an eye on the native Timucuan population and to help guide vessels into the oldest port in the country. But it also drew the English pirate Sir Francis Drake in 1586. After pillaging, Drake and his men burned the tower down.

The United States commissioned Florida’s first lighthouse in the same spot in 1824. It survived until after the Civil War when erosion began to compromise the foundation. Fortunately, a new lighthouse, 350 yards inland, was completed in 1874. Six years later, the original lighthouse collapsed into the inlet.

Today, the St. Augustine Lighthouse is restored, and its grounds are home to a museum, which chronicles and preserves the maritime history of our country’s oldest European settlement. The two-story keeper’s home offers a look into life during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Coast Guard Quarters used during WWII provide another aspect of the area’s history.

Of all the historical sites to visit in this tourist destination, I recommend the lighthouse as the best place for its authentic examination of the past and for its stunning views of coastal north Florida.

Visit the St. Augustine Lighthouse

Hours: From October through February: 9:00 am – 6:00 pm daily. From March through September: 9:00 am – 6:30 pm daily. Hours may vary during holiday season.

Cost (includes climb and admission to the grounds): Adult – $17.95; Children (12 and under) – $12.95; Seniors (60+) $15.95

Check out Native Lands by P.C. Zick set in St. Augustine.

Available in Kindle Unlimited, Paperback, and AudioDanger lurks in the swamps and wetlands of Florida. The Spanish conquistadors threaten the native people. A greedy conglomerate destroys anything in its path. Innocent and passionate people throughout the centuries engage in a battle simply to survive.

Traverse the years from 1760 to the present day in a constantly changing environment as the political thriller unfolds.

Native Lands also goes back in time to form a historical perspective on Florida’s Native Americans. Join Locka and Mali as they lead their tribe of Timucuans away from the Spanish near St. Augustine in 1760 and settle into a new life in the Everglades alongside the Calusa Indians. Their progeny grow and hide in the swamp, attempting to keep their bloodlines pure.

Hundreds of years later, the exiled native Floridians thought to be extinct, rise up and form their own band of warriors to fight a conglomerate intent on destroying the last vestiges of the natural environment of Florida. With the assistance of nature, they attempt to halt the annihilation of the natural world they treasure.

Mangrove Mike, Joey Cosmos, and Rob Zodiac have lived their entire lives with the secret of their heritage kept hidden until they learn that human connections transcend the fear of extinction. Join them, along with Barbara Evans in the Everglades and Emily Booth in St. Augustine as they form the foundation and prepare to fight forces, which are intent on completing manmade “living zones” throughout Florida.

It’s a dangerous journey for this mismatched group of fighters as they attempt to halt the destruction of the natural world they treasure. Cultural boundaries established centuries ago are erased as love and nature seek the balance lost during the battle for power and control of the last of the Florida frontier.

April 29, 2025

SMALL TOWNS ROCK – MONTICELLO, FLORIDA

The centerpiece of Monticello, Florida, thirty miles east of Tallahassee, can be seen from all directions when approaching the downtown of the small town and county seat of Jefferson County. The two main highways into town converge at the Jefferson County Courthouse, which pays homage to our country’s third president.

The Classical Revival structure with French influences was constructed to loosely resemble Monticello, Virginia, the home of Thomas Jefferson. However, in true Old South tradition, the Florida version is pronounced with an “s” sound on the “cello” part. Traffic circles around the courthouse and joins US Highway 90—flowing east and west—with US Highway 19 heading north and south.

Thomas Jefferson died in 1826 one year before the county was formed. Some say the county and town were named to honor his contributions to the founding of the United States. But I found one historical account stating that several of his descendants resided in Jefferson County for many years.

When I first moved to Tallahassee eighteen years ago, Monticello was simply a name on a sign off I-10. But a few years ago, I rediscovered an old friend who lived in Thomasville, Georgia, fifty miles from my home. Monticello sits right smack dab in the middle of both our homes. For the past three years, we’ve been meeting in Monticello for lunch several times a year. We’ve not tired of the restaurants—which are plentiful—nor of the unique shops selling antiques, plants, Tupelo honey, and a multitude of other unique items.

Downtown Monticello

Downtown MonticelloIt’s a gem of a small town. Even though the population hovers around 2,500, the traffic around the courthouse circle shows a vibrant population of residents and visitors on any given day of the week.

Thick forests and rich soil drew the first settlers to the area. Cotton, corn, pecans, and watermelon dominated the economy for decades. During the Gilded Age years, 1865-1902, the wealth of the country changed dramatically as did the lives of its people. Immense fortunes brought folks to Florida’s warm climate, and places such as Monticello and Thomasville thrived.

During this boom time, the first passenger train brought tourists to Monticello in 1888. To help provide services for the influx of folks, wealthy businessman John Perkins built the Perkins Block in 1890. The ground floor held a general store and mercantile shop. The second floor became the Monticello Opera House where plays, vaudeville shows, touring opera companies, and even the circus entertained residents and visitors.

In 1909, across the way from the Perkins Block, the courthouse was constructed. The Latin phrase Suum Cuique is inscribed above its entrance doors. It means “To each his own,” but locals sometimes say it means, “Sue ‘em quick.” The structure dominates the town’s center.

The Perkins Block on the right with the courthouse right at the center of it all.

The Perkins Block on the right with the courthouse right at the center of it all.As happened with far too many small towns across the United States, several things conspired to end the boom in the first part of the twentieth century. A series of diseases killed much of the agricultural livelihood, which began the decline. The spiral toward the depression began. A fire destroyed the town’s largest hotel in 1917. And the death toll rang on Monticello in 1927 when it was decided to reroute the railroad through Lloyd, a small farming community west of Monticello. By then, the depression gripped the community, and the theater eventually closed its doors as did the other businesses housed there. It remained in disrepair until 1970, when private donations, fundraising efforts, and state grants sponsored a restoration project. Today, the theater provides year-round entertainment, and its courtyard is the site of many events, including weddings. It also draws people from Tallahassee and Thomasville, my friend and I included, to its downtown area with six or seven restaurants scattered within walking distance of one another.

To honor its agricultural past and present, each June the town holds a watermelon festival.

This year, the 74th Annual Monticello Watermelon Festival occurs on June 13 and 14, 2025. Click here to learn more.

Thank goodness for the resilience of the people of this country who honor the past and charm visitors with its ingenuity.

April 21, 2025

CELEBRATING EARTH DAY 2025

Ibis and snowy egret in conversation on the Wacissa River, Florida.

Ibis and snowy egret in conversation on the Wacissa River, Florida. Photo by P.C. Zick

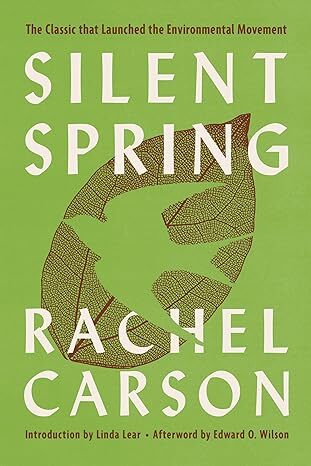

Fifty-five years ago on April 22, 1970, the first Earth Day was celebrated. Maybe the word “celebration” doesn’t quite fit here because its inception came as the result of some horribly tragic events—an oil spill and the discovery by a woman scientist/writer of the harm done to wildlife and humans from pesticides.

All those years ago, organizers saw it as a positive way to respond to the largest oil spill to date in Santa Barbara in 1969. Ironically, on the fortieth anniversary of Earth Day in 2010, news of another oil spill began trickling into the media when an oil rig exploded in the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of Louisiana, killing eleven men working on the rig and doing untold damage to the surrounding area when the gushing oil couldn’t be contained for weeks. Deepwater Horizon isn’t mentioned much these days, but it had a profound impact on me, and I’ve never forgotten.

Many historians credit that first Earth Day in 1970 to the incredible work done by biologist and writer Rachel Carson. I believe the collision of both the Santa Barbara oil spill and the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring brought an awareness to many folks about the harm caused by our advancements in industry and science despite the positive impacts that have been realized. Advancement without care comes with a cost. And the cost results in the loss of human and wild lives as well as destruction to the environment.

Rachel Carson

Rachel Carson

You might ask who is Rachel Carson? I had heard of her prior to moving to Pittsburgh in 2010, but I wasn’t completely aware of her impact on the environment. I wondered why one of the bridges over the Allegheny River in downtown Pittsburgh was named the Rachel Carson Bridge. I learned the author of Silent Spring had grown up in Springdale, Pennsylvania, on the banks of the Allegheny River not far from that bridge.

Rachel Carson’s childhood home on the banks of the Allegheny River near Pittsburgh. Photo by P.C. Zick

Rachel Carson’s childhood home on the banks of the Allegheny River near Pittsburgh. Photo by P.C. ZickBorn in 1907, she grew up just upriver from the city that was coughing its way to becoming the Steel Capital of the World. Carson played in the hills surrounding the river as it wound its way to meet the Monongahela and Ohio rivers in downtown Pittsburgh. When she found a fossil on the banks of the Allegheny, she became obsessed with the sea and the history of nature.

Ms. Carson was a writer from an early age. But in college at Pittsburgh Women’s College—now Chatham University—the study of biology beckoned. She went on to work for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service where her talents as a writer emerged in the writing of boring fact sheets about wildlife. She eventually left the USFWS to write books about the sea. Soon her research led her to learning about illnesses caused by pesticides. Thus began her four year journey in researching and writing of Silent Spring (1962), which exposed the horrors of wholesale spraying of lethal toxic substances on all living things to kill one pest. Her conclusions led to the banning of DDT use.

The shocking and controversial book set in motion a string of actions that eventually led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency and passage of the Clean Air and Endangered Species acts. Unfortunately, she didn’t live long enough to witness the explosive impact of her research and words.

While the book became a bestseller almost immediately, it created a firestorm of vicious attacks on Carson by the pesticide industry and the media. She remarked that her critics represented a small, yet very rich, segment of the population.

An editorial in Newsweek soon after its publication compared Carson to Sen. Joseph McCarthy because the book stirred up the “demons of paranoia.” But that book, no matter its reception, helped save the bald eagle and peregrine falcon and other birds from extinction.

Bald eagles were once endangered by pesticides, but thanks to Rachel Carson, they are now of low conservation concern.

Bald eagles were once endangered by pesticides, but thanks to Rachel Carson, they are now of low conservation concern. Photo by P.C. Zick at St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge, Florida

Rachel Carson didn’t want to write Silent Spring, but she stated in an interview, “the subject chooses the writer, not the other way around.”

I’m a firm believer in the subject choosing the author. When that happens, it’s best to let go and enjoy the gift. And that’s exactly what happened to me in the months after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. I began writing Trails in the Sand because the subject chose me, the words came easily, and the characters became an extension of my family. Click here to check out my blog post on the hows and whys of writing this book.

#FREE Kindle Download – April 20-25

#FREE Kindle Download – April 20-25

April 20, 2025

TRAILS IN THE SAND CELEBRATES #FREE

To start off Earth Day 2025 week, I’m offering my Florida Fiction novel, Trails in the Sand, for free downloads April 21-25.

Click here to download #free trails in the sandWhat does this novel have to do with Earth Day? Everything.

Book Blurb: When environmental writer Caroline Carlisle sets off to report on endangered sea turtles during the Deepwater BP oil spill in 2010, she also uncovers long-kept secrets that threaten to destroy her family. The situation is complicated further by Caroline’s love for her late sister’s husband, Simon. An uproar ensues as Caroline’s southern family embarks on a collision with its past and future. At the same time, the oil from Deepwater Horizon continues to spew forth into the Gulf of Mexico and onto its beaches, creating an urgency to save Florida’s wildlife. It’s in this atmosphere that Caroline discovers the truth about her family and writes noteworthy articles about wildlife rescues.

Her relationship with both her sister, who died from an eating disorder, and her mother, whose grief and depression over the death of her brother years earlier shatters Caroline’s own secrets. An adventure involving parenthood and children and mental illness, Trails in the Sand uses the real events of 2010 as the backdrop for the psychological love stories unfolding with some humor and satire on the world of Florida environmental politics.

If you enjoy books that combine fiction with real world events, you’ll enjoy how the timeline and facts from Deepwater Horizon’s oil spill serve as the backdrop to Trails in the Sand, the recipient of a Green Book Award.

Earth Day 2010 was marked by the explosion in the Gulf of Mexico that killed eleven men and spewed forth oil into the waters off the coast of Louisiana. Four million barrels of oil flowed from the damaged Macondo well over an 87-day period, before it was finally capped on July 15, 2010.

At the time of the explosion, I worked for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission as a public relations director. However, I was attempting to transition out of my job because I had recently married, and I planned to move to Pittsburgh where my husband worked.

In addition, wo weeks prior to the Deepwater Horizon disaster, twenty-nine men had been killed in the Massey coal mine in West Virginia when gases and coal dust ignited. The news media in Pittsburgh–just a few hours from the mine–had been all over this disaster.

These two events have several things in common. The disasters could have been prevented if proper safety standards had been followed by the companies. And they could also have been avoided if the government who created those standards had actually enforced them.

As a writer, I felt drawn to both stories because of how they touched my life. But that book, Trails in the Sand, also addresses several personal issues about family and finding a way to heal the wounds that stretch back generations. All the while the oil spills and the West Virginia community deals with the shock of losing so many lives.

I began writing Trails in the Sand in the months after Deepwater Horizon and the Upper Big Branch coal mine explosion. Forty deaths within two weeks of one another pushed me to write something that might serve as a reminder of two preventable disasters in 2010. Both events touched my life in some way, and both made their way into the writing of Trails in the Sand.

I made the trip back and forth between the two states sixteen times in 2010. I conducted meetings from a cell phone in airports, highway rest areas, and at a dining room table from our small temporary apartment in Pittsburgh.

Every time I started to give my two-week notice to my supervisors, something happened, and my wildlife biologist bosses pleaded with me to stay. During a crisis, the spokesperson for a company or agency suddenly becomes a very important part of the team. Scientists become speechless when looking in the face of a microphone. And all their scientific facts and figures must be distilled and translated into sound bites for the public. That was my job at that time.

Nothing much happened in those early days of the oil spill for the wildlife community, although as a communications specialist, I prepared for worst-case scenarios, while hoping for the best. Partnerships between national and state agencies formed to manage information flowing to the media. By May, some of the sea turtle experts began worrying about the nesting turtles on Florida’s Panhandle beaches, right where the still gushing oil might land. In particular, the scientists worried that approximately 50,000 hatchlings might be walking into oil-infested waters if allowed to enter the Gulf of Mexico after hatching from the nests on the Gulf beaches.

An extraordinary and unprecedented plan became reality, and as the scientists wrote the protocols, the plan was “in direct response to an unprecedented human-caused disaster.”

When the nests neared the end the incubation period, plans were made to dig up the nests and transport the eggs across the state to Cape Canaveral, where they would be stored until the hatchlings emerged from the eggs. Then they would receive a royal walk to the Atlantic Ocean away from the oil-drenched waters of the Gulf.

The whole project reeked with the scent of drama, ripe for the media to descend on Florida for reports to a public hooked on the images of oiled wildlife. Since I was in transition in my job, they appointed me to handle all media requests that came to the national and state agencies regarding the plan. From my new office in Raccoon Township, Beaver County, Pennsylvania, I began coordinating media events and setting up interviews with the biologists.

As the project began in June 2010, I began writing Trails in the Sand. At first, I created the characters and their situations. Then slowly I began writing about the oil crisis and made the main character, Caroline, an environmental reporter who covered the sea turtle relocation project. Then suddenly I was writing about her husband, Simon, who mourned the loss of his cousin in the coal mine disaster in West Virginia. I didn’t make a conscious effort to tie together the environmental theme with the family saga unfolding, but before too long, I realized they all dealt with restoration and redemption of things destroyed. As a result, the oil spill and the sea turtles became a metaphor for the destruction caused by Caroline and her family. I wish the disasters never occurred. But I can’t wave a wand and erase the past. But with strokes on the keyboard, I could create something lasting that might make a difference. At the very least, I made that attempt. And the result is Trails in the Sand.

#FREE Download – Trails in the sand – April 21-25