Rob Wickings's Blog, page 62

December 29, 2013

An hour with Dom, Stu and DocoBanksy

If you’re at a loss for something to do in the Christmas doldrums, allow me to recommend a little light listening.

If you’re at a loss for something to do in the Christmas doldrums, allow me to recommend a little light listening.

New up on the Britflicks website, two X&HTeam-mates go head-to-head in podcast land. Super Stuart Wright is in conversation with Dynamo Dominic Wade on the subject of documentary, art, hoaxes and of course, the upcoming release of DocoBanksy. It’s an illuminating and entertaining hour that shows, I think, the thought processes and sheer hard work that go into modern low-budget factual film-making. A must, frankly.

December 20, 2013

Retro LadyLand: First class cult!

I wanted to push a site that I’ve been a fan of for a while. If you like cult movies and TV, you’ll dig this too.

Retro Ladyland is the brainchild of Charlotte Cooper, an old friend of mine. She runs a vintage shop, Missy Lil’s, and writes for vintage fashion magazines. But she’s a big movie buff, and has poured her passions into Retro LadyLand. She’s managed to snag exclusive and slightly twisted interviews with all sorts of interesting figures from the world of cult and trash film and TV, making the site a bit of a must-read if the notion of reading exclusive interviews with Heather Langenkamp or Betsy Baker floats your boat.

I caught up with Charlotte recently and asked her to explain herself.

ROB:

How did you come up with the notion for Retro LadyLand?

CHARLOTTE:

I was and still do write for a vintage fashion magazine and love it, but sometimes talking endlessly about floral designs and skirt lengths can be a bit… I hate to say it, but a bit dull…

I have always been a celebrifile (I have just invented that word) and thought, lets try and contact someone and interview them and to my amazement the first person I asked said yes! Then I thought about the format, something that would make my interviews ‘stand out’. I had never written fan fiction before, but knew the market was vast, so I thought, why not incorporate both? An interview with a back story and viola, Retro LadyLand (Two capital L’s) was born.

ROB:

What’s the philosophy behind the site. Or rather, to put it in a slightly less wanky way, what is Retro LadyLand designed to do?

CHARLOTTE

I see it like your favourite band singing all your favourite hits at a concert, instead of going to see a band and them playing their new album, which you don’t know and frankly aren’t there for (I think we can all relate to that). In the majority of my interviews, although I do skim over the more up to date aspects of their career (as in Adrienne Barbeau talking about her time in Argo), I like to concentrate on why we love them, their heyday… How we remember them. But most importantly, Retro LadyLand is designed to entertain.

ROB:

You’ve snagged some great interviews with some amazing figures. How on earth did you get hold of them?

CHARLOTTE:

I just e-mail them, politely and sincerely and once I got one ‘biggy’, they all started to say yes… Although the Krankies asked for money!!!

ROB:

What’s the favourite interview you’ve done for Retro LadyLand?

CHARLOTTE:

My favourite is hard, as they are all such lovely people. Listening to Shani Wallis talk about Sinatra, Liberace and Garland was a rush and Heather Langenkamp was a teenage hero of mine. But I think it has to be David Bradley (Kes). He was so lovely and sincere and was so young when he played Billy, but still loves to talk about his time filming with Ken Loach, plus it is also one of my all time favourite films.

ROB:

We love spoilers here at Excuses And Half Truths. So, are there any upcoming treats you can let us know about?

CHARLOTTE:

I have a festive treat for our Christmas special: an interview with Eileen Dietz. Now horror fans will know that name straight away, but if not, she was the Pazuzu, the devil in The Exorcist. The face that gives you nightmares! Also coming up we have Dana Barron, who was the first Audrey in the Vacation movies and I’m very excited about Nancy ‘Robocop’ Allen, coming soon too! Happy reading!

Well, that’s a sack full of goodies. Retro LadyLand is a solid read, and full of interesting material for those of us that love a bit of cult. Thanks to Charlotte for chatting to us. Check out the site, and say hi. Tell ‘em I sent ya.

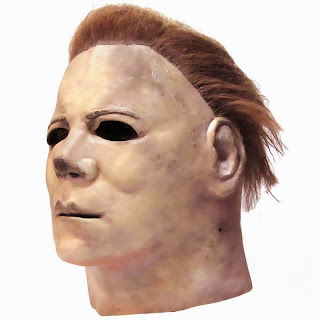

RETRO LADYLAND THIS WAY>>> CLICK on MICHAEL MYERS FOR ALL THE GOODIES!

December 18, 2013

The X(&HT)Mas Bonus Speakeasies: Slayride

Merry Santa!

As our Xmas gift to you, dearest Listenership, here is the second of our bonus Speakeasies. Clive and I are reading each other’s stories from last year’s Zombie Christmas anthology, The Dead Files Vol. 3 (pick it up at Amazon for the zombie fan in your life). This time around, Clive is reading my story of the best Christmas Day ever: Slayride.

Download: xmas-bonus-slayride.m4a

December 17, 2013

Girl Called Johnny: LIVE!

A joint review from Chris Rogers and I of a band that are one to watch in 2014. CHRIS:

However you discover a new band – something played on the radio or as background while you shop, a friend’s recommendation – it’s a fair bet it’ll be via a recording. Hearing a group for the very first time as a live act, though, is something rather special. Loving their material the instant you see/hear them is even better.

For me and Girl Called Johnny, this dual serendipity occurred just four weeks ago when they opened for Texas at the Hammersmith Apollo. The sharp, retro sound of this British three-piece – (frontwoman, guitar and songwriter Karen Anne, Michael on drums and Ross, lead guitar and vocals) leaped out in the instantly-catchy set, and I’ve been playing their eponymous EP – itself recorded live – ever since. When I found out the group were playing The Monarch Bar at Camden this weekend just gone, then, I not only took myself along but recommended some friends come too. Comfortably installed, and after a warm-up from Waiting For Go, Karen and the guys stepped on to the intimate stage in the Monarch’s front room, and off we went…

ROB:

The Monarch gig was my first contact with Girl Called Johnny. A chance phone call from Chris while Clive and I were plotting future Speakeasies led to me cheekily inviting myself along. Chris’ taste is impeccable: if he likes a band, then they’re usually worth checking out.

After a bright bouncy set from Scottish openers Waiting For Go (if you’re into the Two Door Cinema Club/Foals aesthetic, you’ll like these guys) Girl Called Johnny revved up and let loose. The look is black leather jackets, dual Gretsch guitars for that rockabilly twang attack. No bassist, weirdly. Karen is the focus, and wisely so: power pop with a cool blonde up front is always going to be a winning combo, and Girl Called Johnny have honed that look and feel beautifully.

CHRIS:

First single Heaven Knows and Sunshine were punchy, upbeat tracks, driven by Michael’s crisp drumming and terrific guitar from Ross, supported by Karen. Her voice – part honey, part sass – and overall style recall Blondie, a comparison also overheard at Hammersmith and wholly fitting; an edgier, ramped-up cover of Tainted Love made a further connection with that period. Current single Hey Jackie is a rockabilly gem, with a propulsive tune, one of the best choruses I’ve heard for a long time with its almost-overlapped Hey-hey-hey and an explosive cut to it that appears one of Karen’s writing signatures.

ROB:

There’s a retro styling to the songs, a boom-shang-alang that somehow never gets old, never dates. Chris cites Blondie, but there’s a list of influences as long as your arm: from The Smiths to The Cardigans, glam rock to rockabilly to shimmering pop. I only recently found out that the original vocalist for Tainted Love, Gloria Jones, was behind the wheel of the car in which Marc Bolan died. It’s an accurate description of the approach Girl Called Johnny take: love won and lost, hearts stolen and broken, and tragedy lurking around the next corner.

CHRIS:

The first of the group’s stand-out songs was the ballsy Tell That Girl, a cracking song of urban dreams whose cutting lyrics – And you know she’s going out tonight/With those city boys and their bright headlights/Maybe you’ll go down there and start a fight/Or just stay home and cry/Why don’t you/Tell her, tell her, that girl? – and punky riffs really hit the spot. The lack of a bass guitar in the line-up gives all the songs a fleetness of foot that adds plenty but takes nothing away.

But it’s with King of Upstarts, though, that we get a true modern classic. Perfectly crafted in every detail and about, as Karen put it, “getting fucked over, something we can all relate to”, it’s a magnificent, painful piece with Karen’s vocals delivering a real kick to her lyrics. Ross’s guitar solo wrenches, as does the finish, faded on You say, say it’s all over/But you just don’t see what I showed you/I will always love you/I will always love you… Make no mistake, in its rhythms and elegiac tone, this is a Don’t Look Back In Anger for the 2010s.

In contrast closing song Dreams, penned for the band, was a wonderful, uplifting end to the evening, anthemic musically and showcasing Karen and Ross’s beautiful harmonies.

ROB:

The dark edge to Karen’s songs belies how much fun Girl Called Johnny are live. A packed Monarch hollered and bounced to the tunes, and whooped appreciatively when Karen shed her biker jacket to reveal… a lumberjack shirt. You don’t need to show skin to sex it up a bit.

What you’re instantly struck by is the craft and art on display. Classic songwriting with the chops to deliver it in style mean that Girl Called Johnny really are the whole package. If they can win over both Texas fans and the notoriously snarky Camden indie kids, then I think we have us a winner.

CHRIS:

Brighton-born Karen actually worked with Texas on their current album, co-writing several tracks including The Conversation and the brilliant Detroit City (as Karen Overton); on the strength of that and this tight, potent group of songs for her own band, she is a genuine talent to watch. Karen confirmed Girl Called Johnny will be gigging some more – do go. And who knows, we might even get an album soon, that usual way to get to hear a new band…

The new single, Heaven Knows, is now available as a pay-what-you-want download from Bandcamp. For more news, keep an eye on the Girl Called Johnny Tumblr.

Photos courtesy of Chris Rogers, apart from the last one, by yr humble etc.

December 16, 2013

The X(&HT)Mas Bonus Speakeasies: The Promise

As our Xmas gift to you, dearest Listenership, here is the first of two bonus Speakeasies. Clive and I are reading each other’s stories from last year’s Zombie Christmas anthology, The Dead Files Vol. 3 (available at Amazon for that perfect stocking filler). First up, I’m reading Clive’s tale of Christmas shopping hell: The Promise.

Download: xmas-bonus-the-promise.m4a

December 12, 2013

The December Music Speakeasy

Download: december-music-speakeasy1.m4a

In a bare-faced attempt to up the ante, Rob and Clive invite The Little Unsaid, AKA John Elliott, into Studio 2A for some musical shenanigalia. John performs a new song, and covers tracks by Nick Cave and Atoms For Peace.

John also joins us for a robust discussion on the merits of and surprising facts around the world of the cover version. Rob and Clive reveal the music blogs they can heartily recommend (and the ones that they’ll cheerfully never go near again) and guest sound engineer Alex Purkiss shows us up with a radical uptick in sound quality over the bits he’s in charge of. Endearingly shambolic is the way we roll, wise guy! Stop making us look bad!

All this and the usual level of Z-grade pun-slinging and punditry from the crew that put the K in kwality.

The Music Blogs:

NME – nme.com/newmusic

Pitchfork – pitchfork.com/tracks

No Country For New Nashville – nocountryfornewnashville.com

Top House Music Blog – tophousemusicblog.com

Breaking More Waves – breakingmorewaves.blogspot.co.uk

The Von Pip Musical Express – Track of the Day – thevpme.com

Crack in the Road – crackintheroad.com

Real Horrorshow – horrorshowtunez.com

Cruel Rhythm – cruelrhythm.tumblr.com

Popjustice – popjustice.com

Here’s John recording his music for us. Note the professionalism of the studio setup. An upturned bin serves so many purposes…

and for bonus hilarity, the moment when he realised just what he’d let himself in for…

December 8, 2013

States Of Mind: Patlabor On Film – Part 2

If Patlabor the Movie took some risks with its depiction of a Japan failed by its future, Patlabor 2 the Movie is extraordinarily brave in confronting some of the most uncomfortable episodes in its past.

States Of Mind: Patlabor On Film – Part 2

Incursions

by Chris Rogers

The notion of there being little difference between a just war and an unjust peace evokes painful memories in a country dedicated to total war for ten years and which then became a crucial bastion in a new conflict that would last for fifty. Japan’s strategic importance in that Cold War, positioned as she is a short distance from the southern extremities of the then Soviet Union, became clear in 1976 when Ukrainian pilot Viktor Belenko defected and flew his state-of-the art MiG-25 Foxbat interceptor to Hakodate in northern Japan. The incident was the inspiration for Tsuge’s faked aerial incursion, both in the film-makers’ minds and the screenplay – it is referred to by Arakawa.

Particularly delicately drawn is the mistrust, suspicion and conflict between the civil and military powers, something that resonates deeply and uniquely in Japan.

In the summer of 1945, despite the world’s only superpower having subjected their country to the ultimate weapon, the Japanese government vacillated over capitulation for days in a move that led to a tragic second attack. Even then, senior officers in her military attempted a coup d’état in a desperate attempt to prevent the Emperor’s recorded surrender message from being broadcast. Afterward, Japan was yoked by that same superpower to a peace settlement which brought massive investment but also the occupation that she was ready to fight to the end to avoid; for some, such as right wing writer Yukio Mishima, who attempted to inspire a genuine coup d’etat in 1970, this period might be regarded as that unjust peace.

Japan has, constitutionally speaking, no ‘army’, ‘navy’ or ‘air force’, but rather ground, maritime and air ‘self-defense’ forces. All are heavily restricted in their respective duties, to the extent that an armed escort ship for nuclear waste built in the 1990s had to be designated as a coastguard vessel despite it needing to sail well beyond Japanese territorial waters. Japanese participation in just the kind of UN mission depicted in the film’s opening scene has proven extremely problematic for a government trying to play a wider role in the world but whose military is prohibited from combat operations overseas.

The Cold War – one of Arakawa’s proxy wars – brought sustained military investment in Japan by the United States, source of Arakawa’s assertion that “Customs won’t touch anything coming from the US forces”. She is for example one of just three foreign states – alongside Israel and Saudi Arabia – to whom the American F-15 Eagle fighter, the most effective and successful combat aircraft ever built, has been sold – indeed, it appears in the film. This allowed Japan to become a strong bulwark against Soviet aggression, but despite such weaponry she still struggles to uncover the truth about the abduction of her nationals by North Korean agents. And whilst Japan is infused with American culture – baseball is the national sport – the presence of US troops on Japanese soil brought about the infamous Okinawa rape incident, and leaves a legacy of delicate sensibilities that remains to this day.

Other anime draws on Japan’s political past, including Akira, Blood: The Last Vampire, Vexille and Oshii’s own The Sky Crawlers, but none do so quite so perceptively. Mixing this with genre writing and direction of the highest calibre – the air-to-air intercept scene is breathtakingly tense – yields one of the best yet least recognised science fiction films of the last thirty years.

In contrast to the first film, where almost all of SV2 have more or less equal screen time, in Patlabor 2 the Movie the focus is firmly on Nagumo first and Gotoh second, with the other team members far behind. This permits a deeper view of the two and of Nagumo in particular. She is remarkably convincing for an animated character. Her calm, professional demeanour is undermined only by her love for Tsuge and dismay at his betrayal, revealed in the film’s most lyrical and moving moment when Tsuge intertwines their fingers as she handcuffs him at the film’s end.

The other major character in both films is Tokyo itself. The city is lovingly depicted with precise attention to her actual topography, architecture and even season – Patlabor the Movie takes place in the summer of 1999, Patlabor 2 the Movie over the winter of 2001/2002.

Recognisable landmarks in the sequel include the TMPD headquarters, the NTT Building and the Tokyo Stock Exchange. Many of Tokyo’s real bridges are destroyed by Tsuge’s helicopters, and the abandoned Shimbashi underground station, from which SV2 depart to apprehend him, also exists. The distinctive twin ‘turrets’ of the new Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building or City Hall, opened only two years before the film was released and designed by Japanese architect Kenzo Tange, can just be seen towering over an armoured vehicle in the night-time mobilisation scene. It is a neat summary of the narrative, one that is echoed in one version of the advertising poster for the film. At the more intimate scale of the first film, tight alleyways are strewn with rubbish bins and pot plants, a koban (local police box) stands next to a street temple, and the two detectives drink beer sitting on the tiled remains of a long-demolished public bathhouse’s pool.

Technically both of Oshii’s films are a triumph. Made just before computer-generated imagery came to animation – Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell two years later was the first to use the new technology – and thus relying entirely on traditional methods, cel animation was pushed to its limits in the service of a director with an original visual sensibility who wanted to bring the full range of live action techniques to bear.

As already noted weather, including summer sunrises and sunsets and the cold blues, greys and whites of winter, feature strongly in both films, whilst Patlabor 2 the Movie blurs the boundary between the two when, as Gotoh and Nagumo talk in their office after Matsui leaves SV2’s base, the twilight sky outside the window darkens with each successive cut. Man-made counterparts of these natural effects include the dazzling neon and harsh floodlighting of a city at night, highly realistic gun muzzle flashes, scenes washed with red military night-adapted lighting and even shots through a fish eye lens.

Beyond their aesthetic value such moments also often serve to comment on the story. Thus the sunrise metaphor is clear in the first film, while during the detectives’ unobtrusive search of the old town Matsui is at one point seen only as a reflection in a discarded mirror standing against a wall. In the sequel glass screens of all kinds – windows, televisions, cameras, windshields, a fish tank, computer displays, spectacles – feature repeatedly, reflecting the dual layers of reality in the script. Elsewhere a soldier is silhouetted against the window display of a fashion outlet, appearing as a rather sinister mannequin; the shop is called Lumiere at Ombre (‘Light and Shadow’).

Sound also receives attention, adding another dimension. Regular Oshii collaborator Kenji Kawai’s music scores both films, with pumping theme tunes for each yet also exquisitely haunting passages for the dialogue-free montages, Oshii’s principal stylistic signature that also occurs in his Ghost in the Shell features too. Accurate effects include Japanese military pilots talking in English, the universal language of aviation, to the very recognisable aural signature of a video cassette recorder in operation.

All of this was principally Oshii’s vision. He prefers to create his world before populating it, a parallel perhaps with the work of live action director Ridley Scott. Oshii’s love of architecture and cities is reflected in his preparatory technique of walking the streets with a stills camera and photographing everything, recording each item’s textures and shapes. “We see,” he says, “that even a telephone pole is very complicated, with a very strange form, more interesting than a spaceship from a cheap movie.” Scouting Tokyo locations for both films, Oshii visited dockyards, elevated freeways and flood control channels. Chemical refineries influenced the look of the Ark.

A contrast to the harshness of metal, concrete and glass in the film comes from the many birds that quietly populate several scenes. They cluster menacingly on the Ark, surround the dirigibles that float around the city in the sequel, perch on vehicles and poles, feature as part of a music video, form the logo on the side of a truck, and fly up from around Tsuge. The natural world is just as important to Oshii, helping bring the city to life and adding an additional layer.

Organic life of a strikingly different kind is at the core of the third Patlabor film. Conceived after Patlabor 2 the Movie‘s release as a stand-alone OAV but not completed for almost a decade, WXIII: Patlabor the Movie 3 is the only film not directed by Oshii. With a very different, more muted tone and focussing on new characters, the film therefore forms something of a coda to the franchise. The title is usually translated as ‘Wasted 13’, though ‘Waste product 13’ is occasionally encountered. Both are correct, and hint at the main element introduced from the plot of one of the Patlabor manga.

It is the year 2000. Two detectives, Takashi Kusumi and younger partner Schinichiro Hata, investigate a series of attacks on labors that have left behind the mutilated remains of their pilots. All have occurred in or near the Bay. A link with possible contamination of the fish supply is suggested, and Hata forms a relationship with a widowed lecturer, Saeko Misaki, who is also working as a researcher at a nearby bio-laboratory… and mourning her dead daughter, a victim of cancer. As the attacks continue, Kusumi comes to a realisation that will affect all three individuals, whilst Hata’s reluctance to concur is only broken down when confronted by the truth, and its brutal consequences.

The first two films having brought the story of SV2 to a conclusion, members of that team are almost incidental to the third. A nicely-judged appearance early on has the feel of a Steven Bocho crossover cameo, whilst portraying Gotoh as a former colleague of Kusumi provides a link to the detectives of the first film. Even the patlabor/creature battle at the climax is presented in a coolly detached manner, scored entirely to Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 8, commonly known as Sonata Pathétique, through playback of a tape recorded by Saeko’s late daughter.

This last is not accidental. A dolorous mood suffuses the entire film. In the opening scene, a tumbling cloud-filled evening sky is reflected in darkened waters; the buildings of the city are grey and forlorn, an unused stadium, abandoned part-way through construction, the setting for that climax; a cleared house plot, grass-grown and surrounded by a tumble-down wall, stands for a wider emptiness, and Kusumi himself embodies this. Middle-aged, a heavy smoker, and walking with a crutch following an undisclosed accident, he walks through cold subway platforms and streets to the apartment where he lives alone, taking refuge in its tiny, womb-like sitting room, lined floor to ceiling with old vinyl records. The cinematography throughout is mostly leached of colour, like a faded photograph, the only natural light slanting or otherwise intruding into scenes and then only through leaves or shuttered windows. Hata and Saeko watch a performance of Chekov’s The Cherry Orchard, whose themes of the death of a child, living in the past and the impact of profound social change mirror those of the film.

Much of this derives from veteran anime director Fumihiko Takayama. Knowing the limitations of animation’s ability to generate genuine mystery and suspense but also understanding that film in general is a visual medium that should show the ‘how’ of a situation rather than the ‘why’, he opted for maintaining and extending the realistic urban backdrop for the action begun by Oshii, with the everyday in Tokyo – its trains, docks, mini-marts and streets – here rendered even more believably.

Conscious, too, of the pitfalls awaiting the makers of any ‘monster’ story, Takayama was especially keen to help audiences accept an element that, viewed objectively, is as fantastic as the labors themselves. He therefore grounded the genetically-engineered creature in sound real-world science, with the script referencing such concepts as telemores, molecules that protect the body’s cells from cancer-causing abnormalities but in doing so guarantee eventual cell death.

Assumptive analysis of any genre film made around the turn of the millennium is to be avoided, but it is difficult not to read concerns about that particular time into the finished WXIII: Patlabor the Movie 3. The period coincides exactly with what some term the Lost Decade, marking the end of Japan’s global economic primacy, and Takayama himself notes that during the film’s prolonged gestation two specific events that shook the country occurred – the Great Hanshin or Kobe earthquake, in which more than 6,400 were killed, and the Aum Shinrikyo nerve gas attack on the Tokyo underground. That the film-makers found their projections of Tokyo in the near future overtaken by reality even as they completed their work only adds to the overall atmosphere.

There are connections to the previous films beyond SV2’s presence, most notably the unease between the police, the Japanese military and America. The creature is intended as a weapon, presumably for foreign sale, and yet the military is also required by circumstance to help destroy it. Gotoh tells Kusumi of a link to the Marshall Islands, where America tested her hydrogen bombs, whilst the stadium is shown being prepared for a pop video shoot directed by a comically egotistical US film director who speaks English throughout. And yet the contemptuous disregard felt for the lives created and destroyed that are the ‘wasted thirteen’ is wholly Japanese in origin, and acts at least in part as a spur for Saeko to act.

More personal than either of the earlier films, its darkness enlivened by only occasional splashes of colour, WXIII: Patlabor the Movie 3 is a richly layered and thoughtful production. Although a second set of OAVs and a television series – the latter following a separate continuity – were also made, it became the last production to explore the world of Patlabor. Each explored a world of the future, but in doing so inevitably also explored our own world.

Today, ten years later, separatist movements and border disputes still threaten peace in many parts of the world, and the Japanese prime minister himself, seeking to expand Japan’s role in the region and push back the country’s constitution, is accused of ‘new nationalism.’ With such changes in the air, the trilogy rewards repeated viewings not just as an involving and beautifully drawn set of stories, but as a rare chance to understand a people and a country, their past and their present.

Chris Rogers writes on architecture, film and other aspects of visual culture for various outlets and his own website, www.chrismrogers.net

December 4, 2013

States Of Mind: Patlabor On Film – Part One

I’m breaking the very necessary radio silence that occurred over November. Nanowrimo, as ever, took up a great deal of time, and cruel as it may seem, something had to give.

There will be a fat dose of Speakeasy goodness coming up over the next couple of weeks in the form of Xmas treats–keep your ears peeled for that. In the mean time, I’m delighted to host a new longform piece by our friend, the mighty Chris Rogers. He promised us something on the influential Patlabor series, and he’s come through in spades. Over the next two posts, he explores the themes, history and influence of a film series that would come to help define the visual grammar of Japanese SF as it approached the 21st century.

Strap in.

STATES OF MIND: PATLABOR ON FILM

part one: PILOT ERROR

by Chris Rogers

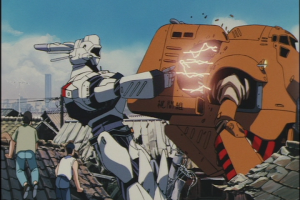

Ten years into the future; a forest outside Tokyo. Night. From the dark sky, massive armoured bipedal machines descend by cargo parachute and retro jets to join soldiers, their faces set, moving quietly through the trees. A stop line is formed; weapons are readied. A rumble of noise becomes a roar as their foe, a prototype flying tank, crashes through the undergrowth towards them. It opens fire; the soldiers reply. Gunfire tears into the tank, but it doesn’t stop. The automatic cannon of the bipeds adds to the unit’s firepower, and now helicopters dive in to attack with missiles. Finally, a spider’s web of cable strung across its path snares the shattered tank and brings it to a halt. As it lies immobile, soldiers close in, warily. They scramble on to the hull and level their guns, ready to confront the renegade crew. The tank’s hatch is forced open. The cockpit is empty.

So begins the anime feature Patlabor the Movie (1989), an absorbing and intelligent techno-thriller that was a great success in its home country but also helped popularise anime in the West. The film became the first of a trilogy, each of which explored the same carefully-realised societal landscape but from very different angles. Thus Patlabor 2 the Movie (1993) is a densely-plotted political drama that audaciously draws on Japan’s troubled history to posit a scenario uncomfortably close to reality, whilst WXIII: Patlabor the Movie 3 (2002) is a sombre side story set between the two earlier productions that fuses characterful introspection with classic monster movie tropes. All three feature narrative complexity, incisive cultural critiques and often exquisite execution to form an intriguing, multifaceted commentary on today’s Japan.

This is perhaps surprising given the genesis of Patlabor as an essentially light-hearted Original Animation Video (OAV) series. Devised by Yuuki Masami of creative collective Headgear and released the year before the first film, it was intended for a teenage audience and was complemented by manga and novel versions. The concepts at the heart of the OAV, however, suggested the potential for a more adult iteration. The involvement of Headgear director Oshii Mamoru in the series must also have made this likely. Oshii would later bring Shirow Masamune’s Ghost in the Shell to the screen as well as his own original live action virtual reality drama Avalon, reflecting his long-standing interest in the dissection of worlds, meditations on life and the interface between the two.

With a plot that built on two episodes of the six-part OAV, production was duly begun on a theatrical spin-off that would bring about this tonal shift. It would, though, retain the series’ depiction of a near-future Japan that seemed, in the economic boom years of the late 1980s, at the very least possible, if not actually desirable.

To accommodate Tokyo’s ever-expanding population, overcome the lack of space brought about by her geographical situation and protect against melting polar ice caps, Project Babylon is conceived: a great tidal barrage stretching across Tokyo Bay, allowing the entire extent of the Bay within to be emptied and reclaimed for settlement (in real life, this has already happened to about a fifth of the Bay’s original area). Making this Herculean endeavour possible is a new construction tool – eight-metre-tall machines of varying design able to walk, lift and manipulate items with the freedom of a human but on a vastly increased scale, machines called labors (the American spelling is deliberate and relevant, as will be seen). Labors are not robots; operated by a pilot seated in the chest cavity, they are an evolution of the excavator, bulldozer and crane in use today, and transform the capabilities of any workforce. With man’s reach extended in this way, and more than 3,500 labors – half of the total number in Japan – maintained and stabled on a vast maintenance platform in the Bay called the Ark, Project Babylon is under way.

But although useful, labors also bring problems. An angry or drunk worker is a danger only to himself, but that same worker piloting a labor could destroy a city block. To fight such labor crime, the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department is equipped with special patrol labors, the derived portmanteau word ‘patlabor’ giving the series its name. Their polished white armour and black detailing reflect the livery of Japanese police cars (and their spiritual ancestors from America), though with its broad shoulder pads, a labor-scaled revolver in a concealed leg holster and a baton, the Shinohara Industries AV-98 Ingram patlabor – the iconic image of the Patlabor universe – is also an exaggerated version of the uniformed street cop common to both countries.

The works follow the lives and missions of personnel from the TMPD’s Special Vehicle (i.e. labor) Section 2, based on its own piece of landfill overlooking the Bay. The Section’s split into two Divisions led by captains of differing personalities – easy-going Kiichi Gotoh and efficient Shinobu Nagumo – prefigures the tensions between ideologies essayed in the first pair of films. He will be central to the first film, she to the second.

This, then, was a fictionalised but highly credible setting that would serve as a basis for more mature stories merging the past, present and future of Japan.

In Patlabor the Movie, a new computer operating system called HOS is installed in each of the Project Babylon labors to further boost output. All seems well. And yet that opening sequence hints at a disturbing problem, confirmed in a later scene in which SV2 battles a rampaging construction labor that cuts a swathe through the city despite its pilot being removed from the cockpit and even after multiple hits from patlabor cryogenic shells.

The cause is eventually discovered by two young SV2 officers: a computer virus, buried in every copy of HOS, that causes the infected labor to start up with no human pilot aboard, act according to its own whim, and continue until it is destroyed. But this is not terrorism, or extortion, or even corporate espionage. It is revenge, the work of Eiichi Hova, HOS’s creator, a brilliant but disaffected software engineer. The question is why, and the answer supplies the film’s melancholic middle act.

Gotoh’s detective friend Matsui and his partner search for clues to Hova’s actions, wandering the back streets of old Tokyo one summer afternoon. They follow Hova’s trail via a dozen previous addresses, moving through narrow alleyways hung with washing, clambering across culverts and exploring derelict warehouses. Whether in decaying tenement blocks or traditional wooden houses, each of Hova’s residences was in a district hemmed in by new skyscrapers and now empty and abandoned. At one site, the foreman hurries them out and the pair watch as a demolition labor tears the building apart.

Matsui briefs Gotoh on his conclusions later the same day under an evening sky, the setting sun reflecting on the waters of the Bay. For Hova, the very technology he serves came to stand not for progress but a disastrous abandonment of tradition and a headlong flight into technological servitude. The corrupted HOS program is Hova’s response, sowing chaos and destruction and plunging man into a new dark age. Chillingly Hova himself, secure in his arrogance, takes his own life even before his plan bears fruit. With SV2 personnel fishing off a jetty as cargo ships slip along the horizon sounding their mournful foghorns, the audience is invited to make its own assessment of a world where man never stops and where the new pushes out the old.

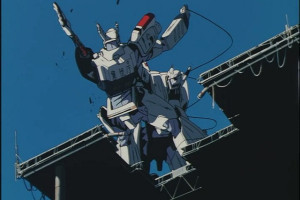

Discovery of the trigger for the virus leads the men and women of SV2 to cross a stormy Bay one night to the Ark in a race to dismantle it before the dormant labors within awake. The outcome of the inevitable battle that follows is kept in doubt through knowledge that the new Type Zero patlabor is also equipped with the new HOS; will it, too, be affected, and turn rogue? Additional tension arises from detection of a single life reading – Hova’s ghost, perhaps – on the roof of the supposedly deserted Ark, a genuinely chilling moment that may owe something to similar scenes in Aliens (Oshiii is a declared admirer of James Cameron). A final stand-off equals Hollywood’s affinity for spectacle whilst including the same touches of lyricism that are seen throughout the film, as the sun rises on the victor.

It can be seen that Patlabor the Movie is rich in references to Japan’s history, in particular its plight during world war two and the years of humiliating yet hugely beneficial occupation by the victorious power that followed. Indeed exploring the complex legacy of this period is arguably the surtext of the film, even above and beyond its genre commitments. The putative destruction of Tokyo threatened by Hova’s plan echoes that visited on the city by American bombing in the closing months of the 1941-45 conflict, whilst the script both celebrates and subverts the advanced technology that arose from that legacy of occupation and reconstruction.

This last was an especially bold statement for Japanese writers to make at a time when their country’s post-war economic miracle, based almost entirely on the design, development and manufacture of domestic and industrial electronics, seemed never-ending. That said, it could be argued that such ambiguity has long been resident in Japan, a country that has always maintained a balance between tradition and modernity. The old and the new also collide in the attitudes and skills of SV2’s team members and their relationships with their families. British anime commentator Jonathan Clements, meanwhile, has noted that Oshii was simply attracted to the idea of a depicting a world in which Japan has to respond to failure of one of the pillars of its success.

Of course it is humanity that is flawed in the Patlabor world, not technology – indeed, we are often invited to feel sympathy for the machines themselves courtesy of several small touches: SV2 pilot Izumi’s affection for her Ingram, nicknamed as it is after a succession of her pets, all called Alphonse; colleague Clancy’s cognizance of the potentially fatal weakness at the heart of her own Type Zero labor; and its agonisingly drawn-out ‘execution’ in the climactic sequence.

The first sequel, Patlabor 2 the Movie, develops these themes, making the dangers posed by ambition and disaffection more explicit and strengthening the differences and similarities between Gotoh and Nagumo in its depiction of their responses. Its script also takes Japanese self-examination significantly further with some ambitious and provocative allusions to the country’s more recent history.

The pre-credits sequence is no less dramatic than that of the original film and is set in the same year, 1999.

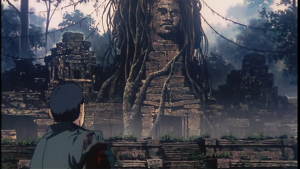

A squadron of Japanese military labors, part of a UN peacekeeping operation to an un-named South East Asian state, is confronted by forces advancing through the jungle toward them. With a minefield behind them Yukihito Tsuge, the unit’s commander, requests permission to engage but is told to hold his fire. As the oncoming threat increases, Tsuge repeats his request but is again rebuffed with the promise of reinforcements. Suddenly incoming missiles blast one labor apart and damage Tsuge’s own machine. More and more missiles slam into the labors, cutting them to pieces. Still denied permission to retaliate but unable to watch his unit be destroyed, Tsuge releases the safety on his labor’s gun and pulls the trigger. Cannon shells arc toward the enemy vehicle, destroying it, but a single final missile drifts lazily toward Tsuge’s labor as if in a dream… Minutes or perhaps hours later Tsuge, his crews dead, his shattered labor stranded, emerges into the stifling heat of a tropical afternoon, bloodied and shaken. He turns and stares at a vast stone Buddha behind him, its ancient face serene and unknowable.

Flash-forward nearly three years to January 2002. Project Babylon has been completed, and Nagumo is speaking at a conference on labor crime outside Tokyo. In the lift afterwards, she meets some former colleagues – all were once students together under Tsuge, at that time a pioneering labor strategist, Nagumo’s mentor, and her lover. She politely deflects a clumsy comment about their relationship, her mind elsewhere as she watches the vastness of the city laid out below.

Driving home that evening, Nagumo encounters a traffic jam leading to the Yokohama Bay Bridge; accessing the local police frequency, she is informed that a bomb threat has been called in on a car parked on the bridge. She waits, patiently and unconcerned – after all, Japan hasn’t been subject to terrorist attack for years. Police labors move in to investigate, but only the audience can see an air-to-surface missile streaking toward the bridge. It climbs, then dives, homing at supersonic speed on the car. The resulting explosion blows a vast hole in the bridge’s road deck, and the government’s feeling of security.

When the media obtain footage of what appears to be a Japanese military aircraft in the area at the time, the disturbing possibility of an accident emerges. But when, shortly afterward, an air defence alert sees two flights of aircraft scrambled to intercept a trio of Japanese fighters on an apparent course to attack their own capital, the stakes are raised much higher. Is this another accident? Terrorism? A coup?

As the aircraft close with each other, the increasingly panicked interceptor pilots call for a target whilst fearing that they themselves will be hit. Air traffic controllers scramble to clear civilian traffic over Narita airport in scenes conceived a decade before the events of 9/11. As the defenders are given permission to engage and shoot-down their own colleagues a catastrophic conflict in the skies above Tokyo seems unavoidable, until it is revealed that – shockingly – both pairs of defence fighters are actually heading toward each other: their ‘enemy’ is a ghost, a false echo planted on a radar screen by a thoroughly convincing manipulation of the Japanese air defence network.

Gotoh and Nagumo are approached by Arakawa, a government intelligence operative, who suggests a culprit even more unnerving than a unit of Japan’s own protectors – a clandestine group of politicians, American military advisors and defence contractors searching for a new enemy after the end of the Cold War. Feeling threatened by Japan’s resolutely pacifist position, they used an American jet with a duped pilot and a hacker to provoke the country into action, fuelling a fresh arms race. It may even lead to America beginning a new, repressive occupation of Japan, to the group’s advantage. Arakawa also has a lead, a senior member of the dissident group with an additional motive – Tsuge.

By creating confusion and fear and pitting the civilian powers against the military, Arakawa states, Nagumo’s former lover wishes to put the Japanese people under the same conditions he was forced to endure when he was left alone and unsupported on his UN mission. As Arakawa says, seeking SV2’s help to apprehend Tsuge without creating an international incident, “Tsuge saw his troops killed under civilian control. So now he’s placed Japan under the same conditions.” He wants, adds Arakawa, “to see what kind of war we create under the same rules as the one he lost his men under.” A Gotoh later remarks, “It’s terrorism under the guise of a coup”.

Arakawa and Gotoh clash from the start, the policeman seeing something oblique and underhand in the spy’s manner, and as their conversation – delivered in voice-over, as scenes of the city unfold during a boat journey – touches on Japan’s difficult past, the opposition between them grows. Arakawa talks of an unjust peace, the latter maintained by having their wars elsewhere, and is bitter at those proxy conflicts and his own country’s tacit support for them – “Japan’s prosperity in built on the corpses from those wars.” Gotoh, meanwhile, believes an unjust peace is preferable to a just war.

Arakawa’s most striking phrase – and a clue to his real status – comes as he reveals his fears that “This country will have to start all over, just like at the end of world war two.” Here lies the true core of the film, setting out the complicated accommodation that took place in the mind of every Japanese after 1945 and which has shaped her ever since.

As Tsuge’s scheme plays out, both sides take positions against each other. The army, flouting orders to stay in their barracks for fear of insurrection, deploys tanks and military labors, stationing them under highway bridges and in the streets. Terrified of outside intervention by America, the government in turn orders the police to surround army bases. The winter snows begin to fall, and the citizens of Tokyo – alarmed, bemused, uncaring – mug for the television cameras, wave or walk by, huddled against the cold. In a country of masked meanings, Gotoh and Nagumo are sucked into a spiral of paranoia and conflicted loyalty, further clouded by the awkwardness of Nagumo’s position as acting commander of SV2 and her latent feelings for Tsuge.

With tension at breaking point, the next phase of his plan commences – actual attacks on strategic points across the city. Helicopters destroy bridges, communications towers and much of the patlabor complement. The city is helpless, cut off, ripe for the picking. When the evidence points to a remote landfill island as the base of Tsuge’s operations, SV2 must once more penetrate the heart of darkness to collapse a plot, this time facing not simple construction labors but armed remote-control robots. The climax will involve the unmasking of Arakawa, and a very personal meeting for Nagumo.

In part two, Chris explores the deeper historical and political threads running through Patlabor 2 the Movie, the architectural and technical aesthetic of both films and the dark third and final instalment, the monster movie WXIII: Patlabor the Movie 3. He also offers some thoughts on the films’ relevance to today’s Japan.

Chris Rogers writes on architecture, film and other aspects of visual culture for various outlets and his own website, www.chrismrogers.net

November 13, 2013

The November Film Speakeasy

Download: november-film-speakeasy.m4a

(if you want a permanent copy, click the link by the player to download the podcast to your computer).

November. Cold, damp, and once you’re past the Halloween/Bonfire Night twofer, there’s nothing to look forward to until Christmas. Oh well, let’s go to the pictures.

Clive and Rob are joined by film-maker Simon Aitken, who braves the 50 Second Flash Film Challenge. We consider the vexed question of remakes, reboots and *shudder* re-imaginings, and the Dice Of Fate is pointing us at music blogs.

Grab yourself a pumpkin spice latte and snuggle in!

Say hello to Simon:

Talk To Us Anyway!

[contact-form]

November 12, 2013

The Three Rules Of Nanowrimo.

Week two of Nanowrimo. The feeling is familiar and yet it has a tang that only comes with the project at hand. I’m on track, on target. It’s good to be writing with this level of intensity again. Taking a break has allowed me to put some thought into the way I approach the task at hand. In particular, it allows me to consider the three rules that have led me to be a four time winner of the great game. Allow me to share them with you now.

1. THOU SHALT WRITE.

Sounds like a no-brainer, right? Of course thou shalt write. It’s what you’re here for. It’s amazing, then, how many people find excuses not to write. Life, work and family will all conspire to get in the way of your precious time alone with your characters and that looming peril you’ve got them facing. So it’s down to you to make sure you have the time to get that 1667-count down.

Why not hook yourself up with a Skydrive or Google Docs account for fuss-free pickup of your thoughts in a lunch-break or a quiet half-hour? If you have a tablet, then there are any number of free or cheap writing apps (I like Daedelus, but WriteRoom is good–and free for the duration of Nanowrimo) that hook into Dropbox or other cloud backup solutions. I use my morning commute to bang out a thousand words, a prime use for what would otherwise be dead time.

While we’re on the subject, it’s worth experimenting to see when you’re at your most productive. Late night or early morning, everyone has a sweet spot when the words just seem to come without effort. Find yours, and you’ve just made the daily writing ritual that little bit easier.

2. THOU SHALT BACK-UP.

Speaking as someone that once lost two days work to a flaky battery on my old netbook, I know the exquisite pain of seeing hard-earned writing vanishing into the aether. I would spare you that pain, Writership.

So, set your main writing platform to auto backup, and shunt your project into a seperate archive. Dropbox is brilliant for that, but there are all sorts of strategies, from emailing your project to yourself to good old USB dumps. Whatever works best for you is fine by me, but make sure you do it, and if you can automate the task so you don’t even have to think about it, so much the better. Your brain’s full enough this month as it is. No need to clutter it up with details if you can help it.

3. THOU SHALT NOT REREAD WHAT THOU HAST ALREADY WRITED.

The tempation to just have a look at what you did yesterday in that wonderful fugue state of creativity, that moment when your fingers just flew over the keyboard, can be overwhelming. Don’t do it. There will be something in there you don’t like. Probably a lot. Before you know it you’re tinkering, tweaking and maybe even taking stuff out. Why wuld you spend valuable time erasing stuff you’ve already written?

There’s a time and a place for editing. It’s called December. November is for writing, and it doesn’t matter if what you put down is pig-ass ugly and clunky as a Lego hand-whisk. It’s wordcount, and you can start putting lipstick and a dress on it later. For now, ever onwards. Don’t look back. There’s a story in front of you, and it won’t take kindly to hanging around while you’re looking for another word that’s like intransigent.

Those are the rules that work for me. There’s one more.

THOU SHALT WRITE IN THE WAY THAT SUITS YOU.

In other words, the way I work might not do the do for you. If you want to write on an endless scroll of typewriter paper like Kerouac, go to it. If you don’t make the 50K, but you manage something that makes you proud, even if you spend the last week in November tinkering, then so be it. Nanowrimo is all about embracing the creative spark inside you, and finding out that it doesn’t burn: it lights the way. However you dio Nanowrimo, I hope you find that spark.

See you at the finish line.