Rob Wickings's Blog, page 50

July 17, 2015

The A To Z Of SFF: A Is For Angry Red Planet

Cyclomedia provides Rob and Clive with some 50’s Z-grade movie hokum. Join the crew of the Ulysses as they explore… the Angry Red Planet!

Warning: this episode contains rat-bat-spider-monsters.

Yes, it’s available to view on Dailymotion. Give it a look!

July 13, 2015

Welcome… To Red Wolf Pines!

Mike Tack is one of the busiest indie horror film makers in the UK. He constantly pushes himself to the limits in getting the best value out of a very limited budget. His latest, Red Wolf Pines, takes that idea and runs hard with it.

Last year, his short Two Careful Owners was selected to play at the Mile High Film Festival in Denver, Colorado. Many of us would see the trip across the big pond as an excuse for a holiday and some networking. Mike used it as the base for Red Wolf Pines. With a DSLR and a few American contacts, he put together the elements for a very Tack-style Western.

It follows three hard-ass cowboys, Corbin, Zeke and Jesse as they track and kill a wanted man. But that man has a brother, the fearsome Kane. Kane has heard of his brother’s death, and he’s looking to settle the score. A simple tale, one that’s been told and retold. But we’re in Tackland now. There’s a vicious twist to this story. For, you see, Kane has a secret. Which is why it’s not sensible for him to find you after dark…

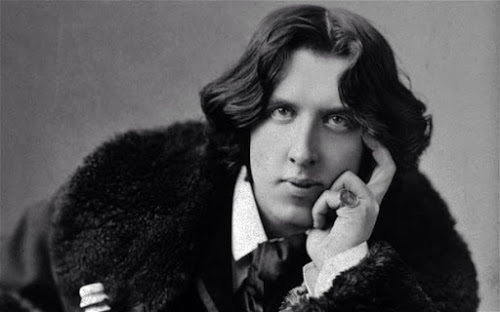

Guess Who?

Guess Who?

With a clever mix of footage shot in two very different locations–the soaring mountains of Colorado and the dark woodlands of, erm, St. Albans, Red Wolf Pines is a very different prospect to Mike’s earlier work. It looks and feels a lot more expensive. Despite this, though, it shares some very Tackian DNA with films like One Careful Owner. Revenge is, as ever, at the heart of the oeuvre, as bullies get their come-uppence at the hands of a much more powerful adversary. These characters are, for the most part, set up for the killing to start in the final act. Tack sees no need to make them sympathetic. The person with which you’re supposed to sympathise is the one they killed in the first three minutes.

This clean, pure narrative style is at the heart of what makes Tack’s tales so approachable. You know what you’re going to get. The fun bit is seeing how it’s going to happen and the gore gags that Mike and his co-conspirator, Tim Richards are going to show us along the way.

It’s nice to see Tack regular Keith Eyles get to do his best Eastwood squint as Kane, and his cast make generally believable gun-slingers (helped with a little judicious ADR from some American friends). A hat tip too for a cameo from our very own Leading Man, Clive Ashenden.

Tres Hombres

Tres HombresThe generous use of Colorado footage, with authentic steam trains and a mounted sheriff in the mix, gives Red Wolf Pines an epic, widescreen feel. Up to now, Tack’s take on urban horror has been claustrophobic, with his characters penned in by iron gates and barbed wire. Even the semi-pastoral of The Allotment feels trapped in toxic suburbia–you can hear the traffic noise. In Red Wolf Pines, Mike is clearly having fun, and the opened frame and Western trappings makes a real difference.

Mike tells me that he’s working hard on a feature script that takes his urban horror pre-occupations in a very different direction. Which means that Red Wolf Pines could be the last short we see from him in a while. A bit of a shame, but then it’s been great to follow a film-maker from his earliest shorts shot on an iPhone to this confident, playful mini-saga. It’s going to be fascinating to see what comes next.

July 10, 2015

The A To Z Of SFF: A Is For “Aye, And Gomorrah…”

More short story action from Rob, Clive and that thrice-damn’d CycloMedia. This episode, they look at Samuel R. Delaney’s “Aye, And Gomorrah…”, a bracing antidote to the macho American view of what space explorers should be like.

Are we not men? Interesting question…

Dangerous Visions, the anthology in which “Aye, and Gomorrah…” appears, is back in print for the first time in decades. It’s one of the most important collections in SF, and and any selfrespecting fan-being should own a copy.

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Dangerous-Visions-MASTERWORKS-Harlan-Ellison/dp/0575108029

July 3, 2015

The A To Z Of SFF: A Is For ‘–All You Zombies–’

This time, Rob and Clive look at a classic bit of SF from one of the masters, Robert A. Heinlein. If you’re expecting macho space battles and right-wing posturing, think again. ‘–All You Zombies–’ is a time travel tale with one hell of a familial twist…

How complicated is it? Well, why don’t we let Ray Stevens try to explain…

July 1, 2015

Encounters And Departures: Miami Vice

One of the great sadnesses in shuttering the X&HT Speakeasy was that we never got the chance to realise the dream of a long-form discussion on the crime films of Michael Mann.

Now, with his latest, Blackhat, available to rent or buy, friend of the blog Chris Rogers attempts to redress the balance with a discussion of arguably Mann’s finest work: his big screen reworking of Miami Vice.

Enjoy this one.

One of these mornings

it won’t be very long

They will look for me

and I’ll be gone

– ‘One of These Mornings’, Moby

Few dramatic film-makers have pursued a theme more relentlessly or more absorbingly than Michael Mann’s near-forty year investigation into characters who commit themselves to a personal code of ethics that defines their loyalties, their actions and their life, and which ultimately defines their fate. Credos are tested to the limit as men fight the unexpected occurrence that disrupts a long-held plan, resist the sudden need to act now, or find themselves acting on an accelerated timescale that is not of their making.

The struggle often sees such characters progressively discarding possessions, homes, friends and lovers as they mark out their own route through this world, leading many to describe the results as existentialist. Given the frequency with which he returns to this subject and the manner in which he has developed and refined his own very specific cinematic space within which these stories occur, Mann himself is surely caught by this analysis.

Crucially he is unconcerned as to whether these men adopt a moral or immoral position, and so is far less interested in the line – or the width of the line – that divides the two than he is with the strength of will needed to retain such a stance no matter what. This is seen in the variation of viewpoint adopted by Mann across the three contemporary crime films he has written and directed that share this theme most clearly, and which can therefore be considered key stages in its exploration: Thief (1980), Heat (1995) and Miami Vice (2006). Whether shifting now to the bad, now to the good, or occasionally stabilising for a moment on the way, Mann treats each equally and instead always tests the ability of protagonist, antagonist or indeed both to hold to their stated beliefs.

Thus in Thief events are seen almost exclusively from the criminal point of view; both Frank and Leo are irredeemable. Each, though, has a very different idea of right and wrong within that world, and both are portrayed as more honest in some ways than the police, who are corrupt and incompetent. With Heat the ethical pendulum falls to its midpoint – there is a clear divide between robber Neil McCauley and detective Vincent Hanna and no suggestion that either will cross it – and so the line becomes a mirror, reflecting the other’s actions.

The perspective swings firmly to the side of law and order in Miami Vice, Mann’s latest iteration of this theme and his feature rendering of the 1984-89 television series created by Anthony Yerkovich for which Mann acted as executive producer. Despite complete immersion in an undercover identity to the extent that he falls in love with a criminal and his partner expresses concerns over “which way is up”, Crockett retains a clear – even fierce – vision of his true purpose.

Yerkovich’s characters were darker, more meditative and more melancholic than is commonly supposed, even before the major shift that occurred in the fourth season. Pared back to their essence and re-formed for the harder sensibilities of the new millennium, they presented an ideal armature for Mann’s enquiry to be built around. In addition, although Mann was the person most directly responsible for setting the programme’s look through his integration of photography, costume, location and music, he directed not a single episode. A theatrical version allowed Mann to correct this and bring his ongoing exploitation of digital photography’s possibilities into that mood mix.

The result is a completely real and utterly present combination of concept, plot and dialogue in which character is conveyed briskly and the whole is delivered in a cinematic envelope stripped of excess and (re)constructed in precise tones. Its success extends beyond Miami Vice’s position as simply a variation on a personal theme; it is arguably the purest, leanest, truest example of its genre yet seen, without a single wasted frame or syllable but with a weight of intent, meaning and emotional impact.

Mann signals his method from the outset, making no concession to convention or context and immediately dropping the viewer into the story via a sensually audacious cold open that is an instant transition between our world and the characters’. Despite being reduced to visual and aural minima, it is stylish and powerful and demands attention, also demonstrating Mann’s understanding of music’s relationship to film. The scene establishes Crockett and Tubbs as men completely in control of their environment, even after an unexpected phone call that alters their immediate plans. This is though the time that begins the testing of Crockett against his beliefs.

When he and Tubbs step out of the throbbing club and into the night air, their situation atop the roof of a downtown high-rise, a sky full of torn cloud in bruised blues, violets and purples, stands as a metaphor for what follows. On that rooftop, they are in a shifting, liminal space above the everyday, where boundaries blur from the sharp and the simple, and what lies beyond is unclear. Further night-time meetings continue this subtle destabilisation, first with their informant Stevens, then with FBI agent Fujima and – pivotally – with Arcángel de Jesús Montoya, compellingly played by Luis Tosar. Although by this point Crockett has already met Isabella, the magnetic influence that risks diverting him from his true course, it is only here, with Mann compressing the presence of Crockett, Isabella, Tubbs and Montoya from town to convoy to car, that a spark is created. The space of that SUV interior – a protective carapace or womb – represents the denied territory that is Montoya’s world and the temptation that accompanies it.

It is important to note that, eschewing the grand, operatic arcs of Heat, Miami Vice is a far more intimate work. The doomed relationship between Crockett and Isabella is at its heart and is responsible for some of its softer passages, countering the mercilessness of the principal action. The film is also about fragility and surface, especially the refraction of truth as it passes through the multiple layers of falsehood borne by almost every character. They may not accept or even know this – some are even misleading themselves. Certainly that applies to Crockett and Isabella but we, like them, are content to believe for now since it gives both an exit, however momentarily, from the surrounding horrors. The refreshing, almost child-like simplicity of many of their exchanges, in direct and very conscious opposition to the cold techno-talk of waypoints, velocities and percentages found elsewhere, reflects this: “How fast does that go?/It goes very fast/Show me…”

The extraordinary scene these lines introduce, almost a tone poem thanks to Mann’s backing of it with Moby’s remix of his track One of these Mornings, is lyrical, hypnotic, taking the characters out of their worlds, suspending them in time and space and acting as a bridge between one reality and another, whether political (America vs Cuba) or personal. It is a moment brilliantly translated by Mann from his screenplay: “In seven seconds they’re doing over 70 knots in strong light, ripped by wind. Behind them are ocean and sky and twenty-foot plumes […] The boat vibrates, the engines scream”

It is also a direct quote from the series…

…and not a casual one – the detectives’ original lieutenant had just been killed, leaving them in limbo and paving the way for the introduction of Edward James Olmos as Castillo and a critical time for Tubbs. In the new film the dreamlike atmosphere is echoed but darkened in the later, static shot of the Miami skyline looming hazily, almost unreachably though actually quite inescapably on the horizon as Crockett returns from his sojourn, having stepped purposefully but temporarily toward his “fabricated identity”.

Whether in Haiti or Havana we see Mann employing another element of the cinematic space he has reserved for these works; an intimate concern for geography and architecture.

A blend of sky, land and buildings particular to each place is important to Mann, who invariably now shoots entirely on location with no studio sets. The importance of architecture to Mann is seen in his screenplay, here describing Isabella’s Cuban home: “The paint on the outside of this house is peeling and patinaed with stain. The yard is overgrown. The stucco fence around the streamline deco facade is crumbling from weather and time…Crockett watches the ocean from the balcony of the futuristic villa in Verdado… A futurism from 1939, peeling aqua, aging science fiction”. The spalling concrete columns and faded paint of the film locations match this exactly, contrasting with the slick contemporary interiors elsewhere. Even the weather and atmospherics are considered, as has been seen.

Mann never loses sight of the story and the characters with these places – their appearance is important, yes, but the selections have significance beyond this. Thus in Mann’s initial draft script, it is notable that the Haiti meet takes place in a graveyard (“Shadows on white limestone monuments. Bird songs”). In the film, the chaos of Cuidad del Este’s streets symbolises the loss of control felt by Crockett and Tubbs as they move into foreign waters; the Classical portico of the Scottish Rite Masonic temple in Miami looms like a floodlit headstone as they drive to the final showdown; illuminated freeway overpasses are portals into other worlds. Even dockside cranes form a stage for the participants’ performances, actors in their own dramas.

This truth-telling sensibility is carried over into the carefully chosen ethnicities of the characters and the actors who play them. Take Fujiyama; a Japanese name, but a Caucasian face and an Irish actor. No explanation is offered for this, and we immediately accept that none is required. Other such melanges appear freely throughout the film – detectably British bodyguards for Montoya, Russian undercover FBI agents working on US soil, Isabella being French-Chinese, from Angola. More such tantalising references are peppered throughout the screenplay, even if they do not translate to the screen – the film’s Castillo has “a past somewhere between CIA and the Jesuits” and there is more detail on the Cold War politics of Isabella’s childhood. In publicity for the film Mann contended that Miami is most usefully seen as the northern tip of South America rather than the reverse, and his scenes have the authenticity of photo-reportage as a result of this perceptive approach to time, place and origin.

In a Mann film, actions are actions and not descriptions of actions. His reputation for designing and directing fire-fights is deserved, and dates primarily from the astonishing robbery scene half-way through Heat. There, it was originally staged in a way that felt unprecedentedly real, but importantly was offered without pretence, simply as another step in the story arising organically from what came before. Much of its impact therefore derived from its unexpectedness. All three principles are the key to Mann’s approach to this most clichéd of tropes and his reinvention of it, and all three inform the reflected equivalent in Miami Vice.

As with his deployment of brand-name products, which are used extensively but always in character and never fetishized, there is none of the swagger around gunplay that finds its way into almost every other comparable film, even with the best directors – a gun is a tool, nothing more and nothing less, and as with any tool, if employed by a professional its usage will appear natural and the result of that usage will be entirely as he expected.

Mann’s endings are special; conclusive yet open, reassuring yet avoiding pat homilies. They reinforce the idea that his films are slices of real lives, happening now, that we have glimpsed through an open door as we walk by. In Miami Vice, Crockett lets Isabella go – indeed, forces her away – and returns to his true path, as “we have no future.” Isabella watches Crocket drive away, just as he watched her when they first truly met.

The moment, lived, is past. Time is luck.

Chris Rogers is a writer on culture, design, architecture and the cross-points between them. You can find more of his work on his website, http://www.chrismrogers.net.

June 26, 2015

The A To Z OF SFF: A Is For Asimov… again.

As anticipated, Cyclomedia wouldn’t let it lie. We’re back with more on the legendary Isaac Asimov, including a spin round the epic Foundation Saga, and a general muse about what it is that has made the author just such an enduring favourite.

I mean, even here in the 27th Century the guy’s a big deal.

June 19, 2015

The A To Z Of SFF: A Is For ASIMOV

It’s impossible to talk about SF without discussing Isaac Asimov. Rob and Clive tease out some of the themes and ideas in the Robot books, and we find out if CycloMedia knows or cares about the Three Laws Of Robotics.

We have the feeling this’ll go to a two-parter….

https://excusesandhalftruths.files.wordpress.com/2015/06/a-is-for-asimov.m4a

June 12, 2015

The A To Z Of SFF: A Is For America 3000

CycloMedia’s love for Chuck Wagner is coming out. He’s landed us with a forgotten classic in America 3000, a film with more hairspray than would be allowed in any movie after 1989.

Prepare for lumpen sexism and clunky, ill-thought out satire… and that’s just from Rob and Clive!

Why yes, you can enjoy the whole thing on YouTube. Please to enjoy.

June 8, 2015

Wilde About Reading with Stephen Fry

A rare treat for the good citizens of Reading (or at least those, like TLC and I, lucky enough to get a ticket) as the Town Hall played host to the brilliant Stephen Fry. He was there to open the inaugural Town Hall Lecture, hosted by Reading University whose vice-chancellor was on hand to master the ceremonies. The idea of the series: to talk about aspects of the town. When the opening subject was chosen, the choice of speaker became obvious. When you want to talk about Oscar Wilde, there's no better man to lead the discussion than Stephen Fry.

Of course, there's a strange tension at the heart of the relationship between Reading and Wilde. We choose to celebrate his stay here, even though it was under the most miserable of circumstances. His incarceration for “crimes against nature” would bear fruit in arguably his most famous work: The Ballad Of Reading Gaol. It wasn't like he came here out of choice, though. It's a delicate balancing act: acknowledging the relationship between the town and the man for both the best and worst of reasons.

Fortunately, Fry's lightness of touch made the evening at the Town Hall the unalloyed joy we all expected. They are in many ways alike: skilled wordsmiths, effortless wits. The two look similar, of course, to the point where Fry played his hero in Brian Gilbert's well-regarded biopic. Stephen gave us some stories about the making of that film, and pieced together his love for Wilde in a talk that, while seeming to meander aimlessly, had a solid structure. We may have gone off the main path on occasion, but we were always secure in our final destination.

We were encouraged to tweet during the talk, but to be honest that would have meant missing out. It was better to simply sit and listen, to let the stories come. This was a rare opportunity, and one that deserved our full attention. This is a man that could effortlessly drop five anagrams for “Reading” into his first five minutes on stage. You can't hashtag that sort of fearsome intellegence.

How does Reading celebrate Oscar Wilde? With the closure of Reading Gaol in 2013, there's an opportunity to make amends, perhaps, to turn the listed building into an arts centre or theatre. I like to think that Oscar would enjoy that notion, particularly if the re-opening was marked with a performance of one of his plays. No decision has yet been made on what to do with the place. That seems a shame, and yet understandable. It's almost as if we need to give the old place a bit of time to air out, to let the darkness in it leach away.

Reading's relationship with one of our greatest writers has always been complicated. But there's room for a proper reconciliation, I think. It's a sign of how far we have come that a celebration of Wilde, incarcerated for the way in which he chose to love, should be hosted by a man who is able to marry whoever he likes without censure. That too, I think, is something at which Oscar would smile.

June 5, 2015

The A To Z Of SFF: A Is For A.P.E.X.

A film that Rob couldn’t finish, a film that Clive hated. Coming out of the Avengers debacle, looks like CycloMedia isn’t going easy on us.

Join the hapless crew of the Ulysses, why doncha, as we try to find something nice to say about 90s time-travel clunker A.P.E.X.

Hey, why should we suffer alone? Come join the “fun.”