D.R. Martin's Blog, page 7

May 20, 2015

Murdoch MacLennan & the Wreck of the Mataafa

I don’t read a lot of nonfiction books, but one I’ve been wanting to get to for a long time is So Terrible a Storm by Curt Brown (2008). It’s an account of the maritime disasters related to the big blow on Lake Superior at the end of November 1905. The event is also known as the Mataafa Storm, after the ore boat that suffered most grievously. This story is of particular interest to me because one of the main characters in it was my great-grandfather, Murdoch MacLennan.

Most of the book’s action takes place in Duluth, at the western tip of Lake Superior. Brown describes how Duluth’s official meteorologist assessed the developing situation—a big storm coming in right on the heels of an earlier one. Captains of some of the boats discounted the warnings and headed out onto the lake, under pressure from their bosses to get in one last trip before the end of the season. In gripping detail, Brown retells what happened on the ore boats—hundreds of feet long and pencil-thin—out in the giant waves, winds, and blizzard conditions. But at the center of it all is the Mataafa.

She was one of the ships that disregarded the warnings, for a season-ending trip out from Duluth. When she returned a day or two later, she had cut loose her barge and was fighting waves taller than houses. The Mataafa made a run for the Duluth harbor entrance, between two long cement piers. Just as she was about to enter, a giant wave lifted up her stern and jammed her bow into the bottom of the lake, cracking her in the middle and swinging her sideways, about seven-hundred feet from shore. She would not move from that position until the spring thaw.

Getting her crew off proved incredibly hard, given the dreadful conditions. That’s where my great-grandfather came in. He was the Captain of the Life-Saving Service in Duluth. (That’s the precursor of the U.S. Coast Guard.) And in the first hours after the Mataafa wrecked, he and his crew were miles down the shore helping an ore boat that had beached earlier. By the time he got to the Mataafa it was getting dark and all he could do was try to shoot lines out to the fractured boat, for a conveyance to bring men to shore. That effort failed. There was no lifeboat available at the scene, and if there had been it would have been suicidal taking it out in the dark. The next morning he managed to get his rescue boat out to the Mataafa, saving crew at the front of the boat. Tragically, nine crew members marooned at the stern froze to death in the night.

I never knew my great-grandfather, who was born on the Isle of Lewis off the west coast of Scotland. I try to imagine what was going through his mind as he supervised this rescue operation that would be the most significant of his career. Did he have any idea of the scope of the tragedy that was about to unfold? What was he feeling when he took the lifeboat out in those fierce waves with his crew of men? Was he thinking that he might never see his wife, son, and daughter (my grandmother) again? And how did he handle the criticism afterwards, some of which made him a scapegoat for the loss of life? Did he resent it at all or did he feel confident that he had done everything he could?

All I can say is that his wimp of a great-grandson could never have done anything as brave as he did those two days in November 1905. Heck, I obsess about my popsicle toes when I go out on an ordinary winter’s day. Whatever the criticism he faced, in my book Murdoch MacLennan was a hero. If you’re a fan of true-life adventure, I highly recommend that you read So Terrible a Storm, a riveting account of a 110-year-old maritime tragedy.

May 6, 2015

KING HARALD’S HEIST Now in Bookstores

My second King Harald mystery, King Harald’s Heist, written under my pen name, is finally in print. And I’ve already gotten a nice review of the new canine cozy from Shalini’s Book Reviews blog. Here’s what she had to say:

“Audry’s canine cozy is an exciting yet laid-back, quick read. His characters are solid and likable, especially Harald. The author writes the dog’s perspective on the murderous situation, adding a great dimension to the story. Well written in an easy style and wonderful language… A highly recommended read.”

If you’re using an e-reader, you can get the book through Amazon, Kobo, the Apple iTunes bookstore, Smashwords, Scribd, inktera, and Tolino. The Nook version on Barnes and Noble should be available soon.

For those who still love the aroma of paper, the new canine cozy can be purchased as a paperback from Amazon or CreateSpace. In coming weeks, bookstores with access to print-on-demand editions will also be able to order it.

April 10, 2015

Eepersip and The House Without Windows: The Brief, Incredible Life of Barbara Newhall Follett

This is a post about two little girls—one fictional, one real. It is also about one of the most fascinating mysteries in American literature.

This is a post about two little girls—one fictional, one real. It is also about one of the most fascinating mysteries in American literature.

Once upon a time, in the early 1920s, an eight-year-old girl in New Hampshire sat down at her parents’ typewriter. She began to peck out the tale of another little girl whose fondest dream was escaping from her parents and living in the natural world.

Some time later, she finished the tale. It was the length of a short novel. She had been writing stories since she was four or five, but this one was of rather greater magnitude, in size and quality. Dad and Mom knew it was something special.

Of course, many parents assume their little offspring precocious and very much above average. And it’s tempting to suppose that the girl’s father and mother were indulging in the same sort of wishful thinking. But these particular parents happened to be literary folk. Dad was an English teacher and writer, and Mom was also a writer. They knew books, and they knew the little novel was quite an achievement for a child their daughter’s age.

Now this was the era of manuscripts often existing as only one copy. No duplicates, no digital backups in the cloud. There was a fire in the family’s house. The only copy of the girl’s book went up in smoke.

But this girl, whose name was Barbara Newhall Follett, was nothing if not determined. By the time she was twelve, she had managed to recreate her lost manuscript—or at least come as close as possible to what she had originally written.

Having surmounted this lofty challenge, she attacked another: she submitted her slim little novel of escape and freedom to Alfred A. Knopf, one of America’s most distinguished publishing houses then and now. That is rather like a twelve-year-old playground ballplayer trying out for spot on the Yankees roster.

Amazingly, Barbara succeeded. Knopf accepted her book. It was published in 1927 to great acclaim. For example, both the New York Times and the Saturday Review of Literature raved about it. Shortly after, she wrote a second novel, based on her real-life sea voyage on a sailing schooner. It was accepted for publication in 1928.

Then things began to fall apart for the young prodigy. Her father left Barbara and her mother, taking up with another woman. Barbara’s efforts to do travel writing with her mother came to nothing. The Great Depression hit. She was left with family friends in Los Angeles for a time and ran away. The case made national headlines.

Ultimately, she was forced to go to work in a secretarial bureau, where she did shorthand and typing. She wrote two more books, which went unpublished. But by the mid-1930s Barbara met a young man and married him. Things went well for a while, but sometime in 1939 she realized that her husband was involved with another woman. Toward the end, she hoped that he would take her back; that they could work things out. But it wasn’t to be.

In early December of that year, Barbara Newhall Follett Rogers, a genuine prodigy of American literature, walked out of her Brookline, Massachusetts apartment with $30 and a notebook. She was never heard from or seen again.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Barbara’s debut work is called The House Without Windows & Eepersip’s Life There. And in its very eccentric way, it is an amazing tale masterfully written.

Barbara’s debut work is called The House Without Windows & Eepersip’s Life There. And in its very eccentric way, it is an amazing tale masterfully written.

Eepersip is a little girl of about the author’s age who wants above all else to escape the limitations and obligations of living in a house with the weights and responsibilities of family. She wants to enjoy a sensual life purely in nature. So she makes her escape and goes to live in a nearby meadow, where she befriends the deer and the butterflies, and develops a fond relationship with Chippy the chipmunk and Snowflake the kitty. She weaves herself a dress of ferns, goes barefoot, and eats roots and berries.

Her parents, of course, have noted their daughter’s absence and come hunting for her. But the grownups in this story prove singularly inept at recapturing the errant child. She escapes their clutches again and again. One of the most interesting things about Eepersip is that she shows no particular sentiment or affection for her mom and dad; she basically wants nothing to do with them, though it seems they’ve treated her with warmth and fondness. The only love she is interested in is the love of the natural world.

(Nowhere in the novel does Eepersip deal with the Darwinian nature of the natural world. For the most part, predation and disease and death play no part in this fable. It is almost all butterflies and flowers and frolicking—lots and lots of frolicking. However well young Barbara may have written, she was still a child with an idealistic, gauzy view of the world.)

Here, Eepersip teaches herself how to live her new life:

For hours every day she practised running, leaping, dancing, and prowling, until she was as fleet as a deer and as soft on her feet as a lynx. She had practised leaping over high objects, and if someone were chasing her, she could now escape being cornered by jumping a fence. She had trained herself until, even without a running start, she could clear the back of a standing fawn; or, with a start, a large buck standing full height. All these exercises made her light as a feather and graceful as a fern.

By and by, Eepersip leaves the meadow, and any chance that her parents have of reclaiming her passes. She proceeds to the seashore and the ocean, leaving Chippy and Snowflake for good. And then it’s on to the mountain peaks. Yes, she’s still barefoot and in her fern dress, and has no trouble at all with frostbite or starvation.

She encounters only two people along the way with whom she chooses to spend time. A random boy who becomes her temporary friend. And her own little sister, whom she spirits away from her mom and dad. But little sister, to Eepersip’s huge disappointment, ends up missing the parents. To her credit, Eepersip takes her back home.

The House Without Windows isn’t only about finding an escape from the dreary world of adults, as embodied by parents. It is about finding bliss in an incredibly idealized natural world. In fact, the book—as it unfolds in Eepersip’s point of view—comprises forty-five thousand words of sheer, extended ecstasy. It is, in its naïve way, a depiction pure hedonism. The girl is over the moon to be in nature for every minute of every day.

In one place, among dark ferns, grew columbine, gay little gypsies curtseying in the breeze. Their colours spoke to [Eepersip] of dawn, gold sunset and white clouds, snow-banks fringed with icicles, night sky entwined with moon beams, black clouds and radiant sun, or orange, yellow, and scarlet leaves—autumn leaves. She gathered some; and made a rainbow wreath of blossoms; and curling about her hair, they danced again…

And…

That day Eepersip was even happier than usual. She floated about, visiting each flower, each bush and tree. She played games with the butterflies, the games she had played on the old meadow that first summer of her life in the House without Windows. When she rested, she sat on top of a laurel-bush, and not a twig bent beneath her. The slightest breeze blew her about, changed the direction of her dance. Butterfly after butterfly flew to her, flock after flock, as if they had some message to tell her; and after each visit she was happier than before. Yes, they were messengers, these happy creatures; messengers who came to whisper her a secret—a secret from Nature, a secret of the beautiful meadow…

And, finally, she becomes what nature has been preparing her for.

She was a fairy—a wood-nymph. She would be invisible for ever to all mortals, save those few who have minds to believe, eyes to see. To these she is ever present, the spirit of Nature—a sprite of the meadow, a naiad of lakes, a nymph of the woods.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

But, of course, the real world was not so kind to Barbara as the house without windows was to Eepersip. It’s hard to imagine what it must be like to achieve such a height at such a young age, then to have everything come crashing down. But that, of course, is the real Darwinian world of art—the author or composer or artist is no more entitled to continued success than the chipmunk or the butterfly or the deer.

And the mystery of Barbara Follett?

Did she live to write another day under some other byline? Did she become a wife and mother in a family that had no idea of her secret? Did she hole up somewhere and work the rest of her life as a secretary or English teacher? Or did she end up a Jane Doe in some distant morgue?

We’ll never know. But her story deserves re-telling. As a biography. As a movie. The House Without Windows deserves a place as a classic of American children’s literature.

If you want to read the book—and I think you should—you can download an e-book or PDF version by clicking down below. There are also links to the website maintained by Barbara’s nephew and to the article in Lapham’s Quarterly that brought Barbara’s incredible story to my attention.

And now, if you don’t mind, I think I’d like to go outside and dance with the crocuses that are beginning to poke up out of the ground.

You can download an e-book copy of The House Without Windows right here.

This is Farksolia, the website devoted to Barbara Follett.

And here is the Lapham’s Quarterly article that aroused my interest in Barbara.

March 23, 2015

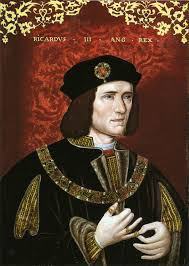

Josephine Tey Defends the King: Was Richard III Framed for Murder?

Something rather remarkable is happening in England this week, as an old villain enjoys some time back in the spotlight.

A couple of years after his bones were discovered lurking beneath the asphalt of a car park in Leicester, that most foul and evil of English monarchs, Richard the Third—the alleged murderer of his young nephews, King Edward V and Prince Richard—is being reinterred amid pomp and ceremony worthy of his former station. In fact, he’s being installed in a new, multi-million-pound tomb in Leicester Cathedral. And nearby a museum has been erected in his honor.

Yesterday, the late king was given the welcome he didn’t receive after the Battle of Bosworth Field. The Guardian reported that hundreds of thousands of people lined the road that the king’s procession traveled. Here’s part of The Guardian’s report:

“King Richard, may you rest in peace in Leicester”, the city mayor, Sir Peter Soulsby said, standing on Bow Bridge, which the last Plantagenet crossed as a battered naked corpse in 1485, his crown, his life and his dynasty lost on the battlefield at Bosworth.

On that August day his body was described by Thomas More as “a miserable spectacle”, slung “like a hogge or a calfe, the head and armes hangyng on the one side of the horse and the legs on the other side”.

You can read the whole article here.

The interment will take place on Thursday and, alas, the Queen will not be in attendance. But the current Duke of Gloucester (Richard was the former duke) will be there, along with Richard’s 16th great nephew, who built his new coffin. There will also be a distant cousin. Those two are the only known relations.

This whole brouhaha about Richard got me thinking about the supreme true-crime mystery of British history. Was the king really responsible for the murder of his two nephews at the Tower of London? The weight of historical judgement is that he was. Of course, it was in the Tudors’ interest that he be declared guilty and their greatest accomplice in this propaganda was the Bard himself, William Shakespeare—whose Richard was the Darth Vader of his day.

But one of Britain’s finest mystery writers, Josephine Tey, begged to differ, in what has been called the greatest English mystery novel of all time (ahead of even Conan Doyle, Christie, and Sayers).

In The Daughter of Time (1951), Tey set her master sleuth—a Scotland Yard inspector confined to bed with a broken leg, going mad from boredom—on the trail of the princes’ murderer. With the help of several sidekicks, Inspector Grant looks into the extremely cold case and comes up with a finding that would have gotten his head lopped off in the Tudor era. Here’s Wikipedia on Grant’s admittedly circumstantial conclusions:

There was no political advantage for Richard III in killing the young princes. He was legitimately made king by an Act of Parliament known as Titulus Regius.

There is no evidence that the princes were missing from the Tower before Henry VII took over.

Although a Bill of Attainder was brought by Henry VII against Richard it made no mention of the princes. There never was any formal accusation, much less a verdict of guilt.

Henry never produced the bodies of the dead princes for public mourning and a state funeral.

The mother of the Princes, Elizabeth Woodville, remained on good terms with Richard and her daughters took part in court events.

The Princes were more of a threat to Henry VII as the foundation of his claim to the crown was significantly more remote than theirs.

Ever since my old history professor assigned our seminar group a reading of Daughter of Time (because he considered it a valuable depiction of effective historical research methods), I’ve been of the opinion that Richard III was framed by his successor, Henry Tudor. His only failure was being on the wrong end of a bloody coup d’état. His naked corpse was crammed into a hastily dug grave in a Leicester monastery, which ultimately became a parking lot.

Richard was by no means a great king of England, but he was a king. And it’s a good thing that he’s finally being given the dignity that he so royally deserves.

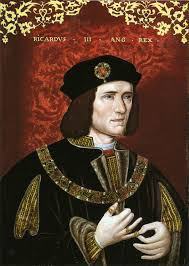

The Reburial of a King: Was Richard III Framed for Murder?

Something rather remarkable is happening in England this week, as an old villain enjoys some time back in the spotlight.

A couple of years after his bones were discovered lurking beneath the asphalt of a car park in Leicester, that most foul and evil of English monarchs, Richard the Third—the alleged murderer of his young nephews, King Edward V and Prince Richard—is being reinterred amid pomp and ceremony worthy of his former station. In fact, he’s being installed in a new, multi-million-pound tomb in Leicester Cathedral. And nearby a museum has been erected in his honor.

Yesterday, the late king was given the welcome he didn’t receive after the Battle of Bosworth Field. The Guardian reported that hundreds of thousands of people lined the road that the king’s procession traveled. Here’s part of The Guardian’s report:

“King Richard, may you rest in peace in Leicester”, the city mayor, Sir Peter Soulsby said, standing on Bow Bridge, which the last Plantagenet crossed as a battered naked corpse in 1485, his crown, his life and his dynasty lost on the battlefield at Bosworth.

On that August day his body was described by Thomas More as “a miserable spectacle”, slung “like a hogge or a calfe, the head and armes hangyng on the one side of the horse and the legs on the other side”.

You can read the whole article here.

The interment will take place on Thursday and, alas, the Queen will not be in attendance. But the current Duke of Gloucester (Richard was the former duke) will be there, along with Richard’s 16th great nephew, who built his new coffin. There will also be a distant cousin. Those two are the only known relations.

This whole brouhaha about Richard got me thinking about the supreme true-crime mystery of British history. Was the king really responsible for the murder of his two nephews at the Tower of London? The weight of historical judgement is that he was. Of course, it was in the Tudors’ interest that he be declared guilty and their greatest accomplice in this propaganda was the Bard himself, William Shakespeare—whose Richard was the Darth Vader of his day.

But one of Britain’s finest mystery writers, Josephine Tey, begged to differ, in what has been called the greatest English mystery novel of all time (ahead of even Conan Doyle, Christie, and Sayers).

In The Daughter of Time (1951), Tey set her master sleuth—a Scotland Yard inspector confined to bed with a broken leg, going mad from boredom—on the trail of the princes’ murderer. With the help of several sidekicks, Inspector Grant looks into the extremely cold case and comes up with a finding that would have gotten his head lopped off in the Tudor era. Here’s Wikipedia on Grant’s admittedly circumstantial conclusions:

There was no political advantage for Richard III in killing the young princes. He was legitimately made king by an Act of Parliament known as Titulus Regius.

There is no evidence that the princes were missing from the Tower before Henry VII took over.

Although a Bill of Attainder was brought by Henry VII against Richard it made no mention of the princes. There never was any formal accusation, much less a verdict of guilt.

Henry never produced the bodies of the dead princes for public mourning and a state funeral.

The mother of the Princes, Elizabeth Woodville, remained on good terms with Richard and her daughters took part in court events.

The Princes were more of a threat to Henry VII as the foundation of his claim to the crown was significantly more remote than theirs.

Ever since my old history professor assigned our seminar group a reading of Daughter of Time (because he considered it a valuable depiction of effective historical research methods), I’ve been of the opinion that Richard III was framed by his successor, Henry Tudor. His only failure was being on the wrong end of a bloody coup d’état. His naked corpse was crammed into a hastily dug grave in a Leicester monastery, which ultimately became a parking lot.

Richard was by no means a great king of England, but he was a king. And it’s a good thing that he’s finally being given the dignity that he so royally deserves.

March 15, 2015

Foody Fun at Fika

Here in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, there are more than a few Norwegians and Swedes. And for the latter, the mother church of Swedish ethnic culture has been the Swedish Institute (SI), near downtown Minneapolis. It’s housed in the ornate old Turnblad mansion and for many years was noted mainly for its modest exhibits of Swedish domestic design and clothing. It was also a favorite spot for weekend brunches, in a vast homely dining room not unlike a church basement.

In recent years the SI has greatly upgraded its exhibits, its shop, its public spaces, and its culinary perquisites—the latter in the form of a wonderful little restaurant called Fika. While there are many higher-end eateries in town, I can’t think of any other spot where you can get such finely made cuisine at such a low cost. You can savor high-end cookery for the cost of a sandwich. The only downside is that the servings are relatively modest—probably better for the waistline.

Sue and I have been to Fika a number of times. Though in its early days, it offered counter service only, now waitpeople serve you in the restaurant’s space in the SI’s handsome, airy main lobby. We visited Fika recently and I wanted to create a little jealousy out there with these shots of our lunch.

Up above is Fika’s lovely baby lettuce salad, with red and yellow beets, marcona almonds, blue cheese, rye croutons, and orange-ginger vinaigrette—one of the tastiest salads in town. Down below are our two “entrées.” The smörgåsar on the right is beer-battered shrimp, pickled hard-boiled egg, dill remoulade, tomato and lettuce, on caraway rye. Next to it is the pork belly small plate, with sunchoke chips, greens, and pear.

Granted, the servings are small, but the taste and texture lovely.

If you find yourself in the Minneapple, do yourself a favor and check out Fika, at 26th and Park.

February 26, 2015

Mary MacDougall Free from Kindle

This is just a heads-up that the first novella in my Mary MacDougall historical mystery series will be available for free from Amazon Kindle Select, beginning tomorrow (Friday, Feb. 27) through next Tuesday (March 3).

This story launches the career of my budding sleuth, Mary MacDougall, as she investigates the Minneapolis kidnapping of two young women in 1901. She suddenly comes face to face with a terrible dilemma. The prime suspect is a man she finds herself very much attracted to. Is he really the talented artist he appears? Or a diabolical criminal?

February 23, 2015

To Watson or Not to Watson?

That is the question.

Right now I’m in the process of working on the third Mary MacDougall mystery, tentatively titled The Widower’s Wrath. But buried in the story—barely noticeable—are some references to a relative of our heroine who seems to have fallen on hard times. Her name is Jeanette Harrison and she is a first cousin of Mary’s mother. What’s her significance?

Well, in the first, original Mary novel—written years ago and published by Xlibris in 2001, now out of print—the tale was told by Jeanette. That first Mary came into being as a mashup of Jeremy Brett’s Sherlock and Helena Bonham Carter’s Lucy Honeychurch. And she needed a Watson. Enter Jeanette.

Now that I’m bringing Jeanette back into Mary’s world in the fourth or fifth book, I need to ask: Does she become the first-person narrator again, like Watson? Do I stay with third person, entirely in Mary’s POV (as in the first three books)? Or do I mix it up, and do different books in the series in the two different POVs? I haven’t decided. Any opinions out there?

Since I have that nice image up above of the four most recent Watsons of the small screen, I wanted to say that I’ve enjoyed them all. But my favorite is Edward Hardwicke, the gent in the bowler. He was Brett’s second Watson—the most grounded and real and sympathetic of them all. I think he was the best Watson ever.

February 15, 2015

Warm Wacky Winter Reading

Anyone who happens to read my blog on the adventures of Travis McGee (and his creator, John D. MacDonald, click here) knows that I enjoy spending warm summer afternoons reading about Trav’s cases in subtropical Florida. What you may not know is that I also enjoy reading about sunny Florida in the depths of the winter—when a little fictional heat is very welcome here in Minnesota.

Just recently, I finished a delightful crime farce set in Key West, by the poet laureate of that funky island town, Laurence Shames. It’s call Tropical Swap and it’s the tenth in Shames’s Key West Capers series.

This time around, an innocent couple from Manhattan house-swap with a stranger from Key West. The problem is that the stranger is a reluctant mob hit man whose wife is the daughter of his mob boss. The NYC couple suddenly find themselves neck deep in mob shenanigans and must ally themselves with the reluctant hit man, his estranged wife, an FBI agent and his sexy suspect, and the inimitable Bert the Shirt (along with his trademark chihuahua). You can get to the Kindle ebook page by clicking on the book cover art.

As good as Tropical Swap is, it’s not even nearly the funniest of Shames’s Key West stories. I’d begin at the beginning, with Florida Straits. If you like your mysteries with a chuckle, you’ll have lots to look forward to as you navigate the wacky world of the Key West mob.

February 8, 2015

Will You Love Me Forever?

Or just until all our lovey-dovey emails and jpegs are corrupted? Until the sweet nothings I send you from my iPhone and laptop someday turn into real nothings?

Back in the day, that wasn’t a problem. Postcards like these from a century ago, with little messages penciled on the backs, are apt to last longer than what we email and Twitter and Facebook. These cards came from my Grandma’s antique shop, which she operated in her farmhouse near Rembrandt, Iowa. By way of legacy, I ended up with a stack of postcards, a punchbowl, and some teacups.

And what do these old postcard Valentines say? Here’s what one of them—addressed to Miss Dora Bauder of Fort Plain, New York, c. 1908—had to say. Hold on now, it’s pretty steamy:

Dearest–How are you? Did you get a cold from the party? My, but I did. We all have been sick since then. Everyone that was there has this awful cold. Love, Margaret.