Bathroom Readers' Institute's Blog, page 79

July 28, 2016

The End of the Videotape

Sure, the “VHS era” ended more than a decade ago with the arrival of DVDs, and then streaming video, but now it’s official: the last VCR will roll off the assembly line in 2016. Here’s a look at some other big lasts in the world of VHS.

The Last VCR

By 2012, two companies still made VCRs: Panasonic and Funai, both headquartered in Japan. Panasonic ejected from the business that year, leaving Funai the last company standing. As of July 2016, Funai will also press “STOP” on VCR production. A Funai spokesperson said that it no longer makes economic sense for the company to make videocassette players when the main market for the format are families and institutions that want to transfer home movies and old educational materials, respectively, to digital formats. That means Funai will now produce “combo” VHS-DVD machines. In 2015, Funai manufactured 750,000 VCRs; that’s a lot, but down from the 15 million it churned out in 2000.

The Last Movie Released on VHS

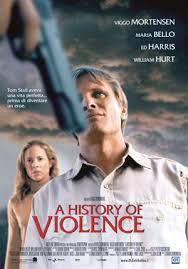

The Last Movie Released on VHSVCR’s have been readily available, but new content hasn’t been. The last movies released on VHS came out a decade ago. The last major Hollywood release on videotape in the U.S. was the 2005 movie A History of Violence. In Europe, it was the 2006 fantasy Eragon. Late in 2006, Disney/Pixar made a very small run of VHS copies of Cars.

VHS vs. Betamax

VHS won the home video “format war” of the early ‘80s. Developed by JVC but sold by many companies, VHS tapes were cheaper and more plentiful than Sony’s technically superior but expensive and proprietary Betamax. VHS was the industry standard by 1986, but blank Betamax tapes were still produced for a small but loyal consumer group. The last Betamax tapes came out of a Sony factory in November 2015.

Blockbuster Video

At its peak, there were 9,000 Blockbuster Video locations where consumers could rent videotapes, and then DVDs. Competition from Netflix and Redbox led to the company’s bankruptcy in 2010. The remaining 1,700 stores were sold to Dish Network, who slowly shut down almost all locations by 2013. As of 2016, there are 15 Blockbuster Video stores left, but all are independently owned and operated by franchisees that have paid Dish Network for the right to use the once mighty Blockbuster name.

The post The End of the Videotape appeared first on Trivia Books and Facts | Uncle John's Bathroom Reader.

July 26, 2016

R.I.P. to the Secret Queen of the Movie Musical

Marni Nixon passed away this week at age 86. She sang in some of the most popular movies—especially musicals—of the all time. You’ve definitely heard her voice, but you probably don’t know her name or what she looks like. Here’s why.

Born in California in 1930, Nixon was a classically trained soprano, boasting an incredibly clear tone and wide range similar to that of an opera singer. She sang with the New York Philharmonic and was a frequent collaborator of composer Leonard Bernstein, but Nixon primarily worked in film. When movie musicals were still a major film genre in the 1950s and ‘60s, the studios would cast actresses for their acting chops or box office bankability—whether or not they could actually sing. No matter, because the producers would hire Nixon, who would sign a non-disclosure contract agreeing that she’d never tell reporters that it was really her voice behind Hollywood’s leading ladies. But she was so widely used in Hollywood that her identity was hardly a secret. (It also explains why all of the female leads in classic movie musicals all sounded so much alike.)

The King and I (1956)

Deborah Kerr earned an Oscar nomination for her portrayal of Anna Leonowens opposite Yul Brynner as the King of Siam. She did the acting, and Nixon did the singing, including the standard “Getting to Know You.” For her contributions, Nixon was paid standard session singer fees, for a grand total of $420.

West Side Story (1961)

In The King and I, Kerr was aware someone else would do her singing. That wasn’t the case on the set of West Side Story. Natalie Wood (Maria) reportedly had no idea that her singing was going to be replaced in the final film with Nixon’s takes. That’s Nixon singing “I Feel Pretty” among other songs. She also provided Rita Moreno’s parts in the “Tonight” quintet. Nixon asked for soundtrack royalties, but she didn’t get them. However, composer Leonard Bernstein privately signed a contract with Nixon giving her ¼ of 1 percent of his royalties.

My Fair Lady (1964)

In 1964, the film adaptation of My Fair Lady was so popular that it was revived in New York. Marni Nixon played the lead role of Eliza Doolittle. That same year, she provided the singing for the character in that same movie adaptation, as producers decided Audrey Hepburn didn’t have the vocal chops for songs like “I Could Have Danced All Night.”

The post R.I.P. to the Secret Queen of the Movie Musical appeared first on Trivia Books and Facts | Uncle John's Bathroom Reader.

History of the American Party System, Part I

American politics is—for better or for worse—entrenched in a two-party system. But the Founding Fathers never even intended for there to be political parties. Here’s the first part of the story of how we got the Dems and the Repubs. Click here for the second part of the story.

PARTY POOPERS

PARTY POOPERSFor all the diversity of opinion among the Founding Fathers in the 1770s, there was one thing that virtually everyone agreed upon: political parties were a very bad idea.

In his farewell address as president, George Washington referred to political parties as “the worst enemy” of democratic governments, “potent engines by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will subvert the power of the people.” Alexander Hamilton equated political parties with “ambition, avarice, and personal animosity.” And Thomas Jefferson could hardly agree more: “If I could go to heaven but with a party,” he wrote, “I would not go there at all.”

ENGLISH LESSONS

The Founding Fathers’ abhorrence of political parties was in response to the partisan politics that characterized England’s House of Commons. The Commons was supposed to serve as a check on the power of the monarch, but successive kings had been able to use their vast wealth, power, and control of public offices to create a party of royalists. Thus, it had been reduced to members fighting among themselves instead of working together to advance the common good.

This was what the Founding Fathers were trying to avoid in the United States: warring factions that would pursue selfish interests at the expense of the nation.

But what exactly was the national interest? And if the Founding Fathers couldn’t agree on what the national interest was, who among them got to decide? These fundamental questions caused the first factions to form in American political life.

FIRST FEUD: THE ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION

FIRST FEUD: THE ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATIONBringing the original 13 colonies together to form the United States had not been easy. The Founding Fathers drafted the first U.S. Constitution, the Articles of Confederation, in 1777, but it was flawed. The Americans had just won independence from one central government—England—and they were reluctant to surrender the power of the individual states to a new central government, so they intentionally made that government weak.

But it soon became obvious that the federal government established by the Articles of Confederation was too weak to be effective at all. The most glaring problem was that it had no power to tax the states, which meant that it had no means of raising money to pay for an army to protect its territories from encroachment by Britain and Spain. In 1787 a constitutional convention was held in Philadelphia to draw up an entirely new document.

It was during the debates over the creation and ratification of the new constitution that some of the first and most significant political divisions in American history began to emerge. Those who supported the idea of strengthening the federal government by weakening the states were known as “Federalists,” and those who opposed the new constitution became known as the “Anti-Federalists.”

The Federalists won the first round: 9 of the 13 states ratified the U.S. Constitution, and Congress set March 4, 1789, as the date it would go into effect. Elections for Congress and the presidency were held in late 1788. George Washington ran unopposed and was elected president.

TROUBLE IN THE CABINET

TROUBLE IN THE CABINETWashington saw the presidency as an office aloof from partisan divisions and hoped his administration would govern the same way. But by 1792, Washington’s cabinet had split into factions over the financial policies of Alexander Hamilton, the secretary of the treasury.

Perhaps because he was born in the British West Indies and thus did not identify strongly with the interests of any particular state, Hamilton was the foremost Federalist of his age. He strongly believed in using the power of the federal government to develop the American economy. In 1790 he proposed having the government assume the remaining unpaid Revolutionary War debts of the states and the Continental Congress. This would help establish the creditworthiness of the new nation, albeit by enriching the speculators who bought up the war debt when most people thought it would never be repaid. Hamilton’s plan also meant that states that had already paid off their war debt would now be asked to help pay off the debts of states that hadn’t, which added to the controversy.

Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson supported the new Constitution but had Anti-Federalist leanings. He grudgingly agreed to support Hamilton’s plan, on one condition: Hamilton had to support Jefferson’s plan to locate the new capital city on the banks of the Potomac River. Hamilton agreed.

Hamilton got his debt plan, and in return Jefferson got Washington, D.C. (Jefferson later regretted the deal, calling it one of the greatest mistakes of his life.)

A BATTLE ROYAL

Then in December 1790, Hamilton proposed having Congress charter a Bank of the United States as a means to regulate U.S. currency. This time Jefferson thought Hamilton had gone too far. He vehemently opposed the idea, arguing that a national bank would benefit the commercial North more than the agricultural South (Jefferson was a Southerner), and would further enrich the wealthy while doing little to help common people.

Hamilton’s financial policies, Jefferson said, were intended to create “an influence of his [Treasury] department over the members of the legislature,” creating a “corrupt squadron” of congressmen and senators who would work “to get rid of the limitations imposed by the Constitution [and] prepare the way for a change, from the present republican form of government, to that of a monarchy, of which the English constitution is to be a model.”

Like Jefferson, Hamilton deplored political parties. But he and his supporters were also adamant about chartering a national bank and strengthening the powers of the federal government. Faced with the determined opposition of Jefferson and his allies, they began to organize what became known as the Federalist Party. The young nation had its first political party, but another one was right on its heels.

Click here for the second part of the story.

The post History of the American Party System, Part I appeared first on Trivia Books and Facts | Uncle John's Bathroom Reader.

July 25, 2016

The High-Tech Toilet Report

Here at the Bathroom Readers’ Institute, we like to keep you up to date on the all the latest breakthroughs in toilet technology. Here are some potties on the cutting edge of bathroom science.

So fancy!

Bathroom fixture company Kohler offers a model called the Numi. It’s loaded with features that turn using the facilities into a luxurious experience. The Numi has sensors that can tell when a user is approaching (and leaving), so the lid opens and closes automatically. A touch-screen display allows multiple users to set their profiles—such as what temperature and pressure they want the bidet to clean them up when they’re done, what temperature they want the heated seat (and toe warmers), and if they’d like the built-in speaker system to play music when they sit down to cover up any sounds their body might make. It’s also got an illuminated display (for when nature calls in the middle of the night) and a charcoal-powered deodorizing system. Cost of the Numi: $6,400.

So clean!

Toilet manufacturer American Standard has introduced technology that addresses what’s probably the worst thing about toilets: how gross it is to clean them. Enter: VorMax. VorMax-outfitted toilets have a specially curved rim to ensure that solid waste does not stick around. Other surfaces are treated with substances that equally discourage material from staying. Coupled with one of the most powerful flushes on the market triggering jets of water, American Standard calls VorMax “the cleanest flush ever engineered.”

So sleek!

Design Odyssey’s Vertebrae is so named because it looks like a human spine with all of those bones sticking out. It’s also much more than a toilet—the Vertebrae is an entire bathroom’s worth of necessities in one tall, space-saving silver tower. A sink, toilet, and shower are housed in modules within the column, and each pulls out. A user could even use all three at the same time. The cost: as much as $15,000.

The post The High-Tech Toilet Report appeared first on Trivia Books and Facts | Uncle John's Bathroom Reader.

Join the Party: The Democratic-Republicans

After the birth of North America’s first political party: the Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, the road was paved to create the two parties that we are most familiar with today: The Republican and Democratic parties. Here is how those to parties came to be.

Meeting of the Minds

As Hamilton was mobilizing his people, so was Thomas Jefferson. In May 1791, he and fellow Virginian James Madison made a trip to New York to meet with State Chancellor Robert Livingston, New York governor George Clinton, and U.S. senator Aaron Burr. According to the book The Life of the Parties by A. James Reichley, “The meetings among the New York and Virginia leaders, however informal, were among the most fateful in American history. The first links were formed in an alliance that was to last, in one form or another, for almost 150 years and that was to be a major shaping force in national politics from the administration of Jefferson to that of Franklin Roosevelt.”

As Hamilton was mobilizing his people, so was Thomas Jefferson. In May 1791, he and fellow Virginian James Madison made a trip to New York to meet with State Chancellor Robert Livingston, New York governor George Clinton, and U.S. senator Aaron Burr. According to the book The Life of the Parties by A. James Reichley, “The meetings among the New York and Virginia leaders, however informal, were among the most fateful in American history. The first links were formed in an alliance that was to last, in one form or another, for almost 150 years and that was to be a major shaping force in national politics from the administration of Jefferson to that of Franklin Roosevelt.”

Jefferson, Madison, and the others saw themselves as defenders of the new republic against Hamilton and the “monarchical Federalists.” The party they formed became known as the Democratic-Republicans, or Republicans for short. Historians consider them the first opposition party in U.S. history, as well as the direct antecedent of the modern Democratic Party.

The Alien and Sedition Acts

The Democratic-Republicans lost their battle: Hamilton pushed his bank legislation through Congress, and President Washington signed it into law. They lost another major battle in 1792 when Governor Clinton ran against John Adams for vice president and lost. A third defeat came in 1796 when Washington declined to run for a third term as president: Jefferson ran for president against Vice President Adams…and lost by only three electoral votes.

In 1793 France—which was in the throes of its own revolution—declared war against England, giving the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans something new to disagree about. The Jeffersonian Republicans sided with republican France, and the Federalists sided with England. But neither side thought the United States should get involved in the war. Partisan emotions intensified in 1796, when the French began an undeclared war on American shipping as part of their war against England and refused to receive President Adams’s minister to France.

Angered by the insults, the Federalists began preparing for what they thought was an imminent war with France. They tripled the size of the army, authorized the creation of the U.S. Navy (the Continental Navy had been disbanded in 1784), and then in the face of the unanimous opposition of the Democratic-Republicans in Congress, passed what became known as the Alien and Sedition Acts.

The Alien Acts said that aliens (who were assumed to have Democratic-Republican leanings) had to live in the United States for 14 years—up from 5—before they would be eligible to vote. The acts also permitted the detention of citizens of enemy nations and increased the president’s power to deport “dangerous” aliens. The Sedition Act outlawed all associations whose purpose was “to oppose any measure of the government of the United States,” and imposed stiff punishments for writing, printing, or saying anything against the U.S. government.

Reading Between the Lines

By the time the Alien and Sedition Acts expired or were repealed four years later, only one alien had been deported and only 10 people were convicted of sedition, including a New Jersey man who was fined $100 for publicly “wishing that a wad from the presidential saluting cannon might ‘hit Adams in the ass.’”

But no one knew that back in 1798. To Jefferson and his supporters, it was obvious that the Alien Acts, and especially the Sedition Act, were targeted at them. Republicans could now be fined or jailed for speaking out against the Adams administration, and if they weren’t U.S. citizens, they could even be deported.

The fact that the Sedition Act expired after the 1800 presidential election seemed to prove their suspicions that the law was intended to curb Anti-Federalist dissent. While the acts were in force, Adams and the Federalists were legally protected from Democratic-Republican criticism, but if they happened to lose the 1800 election, the expiration of the Sedition Act would leave them free to criticize the Democratic-Republicans.

There was more: The Democratic-Republicans also feared that Adams, having tripled the size of the army, would begin using it against his political opponents. As if to confirm their fears, in 1799 Adams called out federal troops to put down an anti-tax rebellion led by Pennsylvania farmers opposed to taxes levied for the anticipated war with France.

The Democratic-Republicans were convinced that if the Federalists remained in power, democracy’s days were numbered, so they embarked on their strongest effort yet to capture the White House and Congress.

A Tough Call

John Adams had mixed feelings about running for reelection. He hated living in Washington, D.C., and he hated being president. The president “has a very hard, laborious, and unhappy life,” he warned his son John Quincy Adams. “No man who ever held the office of president would congratulate a friend on obtaining it.” And now that he was completely toothless, he was incapable of making public speeches in support of his candidacy for reelection.

The only reason Adams ran at all was because he was determined to prevent Jefferson from getting the job. Adams liked Jefferson personally, but he saw himself and Jefferson as “the North and South poles of the American Revolution.” He strongly disagreed with Jefferson’s views on government and the Constitution, and feared that Jefferson would drag the country into a European war to defend France.

Change of Fortune

The Democratic-Republicans, who believed that freedom was on the line, had no such reluctance—although Jefferson, announcing that he would “stand” for election rather than “run” for it, remained at his Monticello estate during the campaign. The party fought a hard campaign for him.

On election day, Adams carried New England, and Jefferson won most of the South. New York proved to be the swing state, which helped Jefferson, because his running mate was Aaron Burr. As founder and head of the Tammany political machine in New York, Burr was able to deliver the state to Jefferson, allowing him to win the presidency with 73 electoral votes to Adams’s 65. The Democratic-Republicans also won control of both houses of Congress.

Federalist Farewell

The Federalists had accomplished much in the years following the Revolution: They had succeeded in drafting the U.S. Constitution, which strengthened the power of the federal government; they had enacted economic programs that strengthened credit and helped the economy grow.

But by 1800 their best days were behind them. “Federalism, as a political movement, was a declining force around the turn of the century,” historian Paul Johnson writes in A History of the American People, “precisely because it was a party of the elite, without popular roots, at a time when democracy was spreading fast among the states. Adams was the last of the Federalist presidents, and he could not get himself reelected.”

The Last Straw

It got worse for the Federalists. They vehemently opposed the War of 1812, and in the fall of 1814, when things seemed to be going very badly for the United States, Federalist delegates from New England met secretly in Hartford, Connecticut, to draft a series of resolutions listing their grievances with the federal government, which a negotiating committee would then bring to Washington, D.C. Some of the delegates to the secret convention had even discussed seceding from the Union.

Bad timing: By the time the negotiating committee arrived in Washington to protest the war, it was not only over, it had actually ended on a positive note, thanks to General Andrew Jackson’s victory in the Battle of New Orleans.

When the rest of the country learned that the Federalists had been holding secret meetings to contemplate splitting off from the rest of the country, the party’s image took a pounding. “Republican orators and publicists branded the Hartford convention an act of subversion during wartime,” A. James Reichley writes, “ending what was left of Federalism as a political force.”

But the die was cast. In spite of themselves, the Founding Fathers had created what they most feared: political factions. The era of the two-party system in the United States had begun.

The post Join the Party: The Democratic-Republicans appeared first on Trivia Books and Facts | Uncle John's Bathroom Reader.

July 19, 2016

Samuel Johnson’s Wicked Words

In 1755, famed critic and writer Samuel Johnson released A Dictionary of the English Language. Compiled over a period of nine years, it became the standard English dictionary until Noah Webster released his in 1828. But it’s anything but “standard”—Johnson’s definitions are often witty, personal, subjective, and quirky.

Politician: 1. One versed in the arts of government; one skilled in politicks. 2. A man of artifice; one of deep contrivance.

Oats: A grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland appears to support the people.

Sock: Something put between the foot and the shoe.

Universe: The general system of things.

Distiller: One who makes and sells pernicious and inflammatory spirits.

Fart: Wind from behind.

Jogger: One who moves heavily and dully.

Dull: Not exhilarating; not delightful; as, to make dictionaries is dull work.

Alligator: The crocodile.

Network: Any thing reticulated…at equal distances.

Reticulated: Made of network.

Monsieur: A term of reproach for a Frenchman.

To worm: To deprive a dog of something, nobody knows what, under the tongue, which is said to prevent him, nobody knows why, from running mad.

Shabby: Mean; paltry. [A word that has crept into conversation and low writing, but ought not to be admitted into the language.]

Antipodes: Those people who, living on the other side of the globe, have their feet directly opposite to ours.

Etch: A country word, of which I know not the meaning.

Novel: A small tale, generally of love.

Patron: Commonly a wretch who supports with insolence, and is paid with flattery.

Melancholy: A disease, supposed to proceed from a redundance of black bile; but it is better known to arise from too heavy and too viscid blood: its cure is in evacuation, nervous medicines, and powerful stimuli.

Ruse: A French word neither elegant nor necessary.

Lexicographer: A writer of dictionaries; a harmless drudge.

X: X begins no word in the English language.

The post Samuel Johnson’s Wicked Words appeared first on Trivia Books and Facts | Uncle John's Bathroom Reader.

July 18, 2016

4 of the Weirdest Ever Saturday Morning Cartoon Shows

24-hour cartoon networks and streaming video pretty much killed the Saturday morning cartoon. But for all of the classics like The Smurfs and Scooby-Doo to watch while you ate your sugar cereal, there are dozens more that came and went pretty quick…with good reason.

Chip and Pepper’s Cartoon Madness (1991)

In the early ’90s, twin brothers Chip and Pepper ran a designer jeans label in Winnipeg, Canada. Their clothing became very popular in Canada, and the brothers’ photogenic appearance (they both had long, blond hair) didn’t hurt. They appeared frequently on Canadian television, and NBC president Brandon Tartikoff was sent the footage. He liked the Fosters so much he gave them…a Saturday morning cartoon. In 1991, Chip and Pepper’s Cartoon Madness premiered, with the Fosters (both live action and animated) hosting old cartoons interspersed with comedy sketches and celebrity interviews. It lasted one season, and Chip & Pepper returned to fashion design.

Rubik, The Amazing Cube (1983)

There’s arguably nothing more definitively ’80s than the Rubik’s Cube—the handheld puzzle game that delighted and infuriated millions. There wasn’t a whole lot that could be done to expand the fad, but NBC found a way with a Saturday morning cartoon. In that world, Rubik is a living, breathing magical creature that is taken care of by three children when an evil wizard loses him. Among the voice talent was a young Ricky Martin. Fun fact: Rubik was the first TV show in American history to feature a predominantly Latino cast of characters.

Rick Moranis at Gravedale High (1990)

It’s a clever enough premise for a cartoon: all of the classic movie monsters—Dracula, Frankenstein, the Wolfman, etc.—are teenagers and they all go to high school together. But for some reason, their main teacher is Ghostbusters and Strange Brew star Rick Moranis.

The Robonic Stooges (1978)

The Three Stooges are back for a whole new generation…in cartoon form…and they’re robots for some reason.

The post 4 of the Weirdest Ever Saturday Morning Cartoon Shows appeared first on Trivia Books and Facts | Uncle John's Bathroom Reader.

July 15, 2016

Car Name Origins

What’s a Kia? Or a Fiat? Here are the stories of how your car got its name.

Alfa Romero

The company began in Italy in 1910 as Anonima Lombarda Fabbrica Automobil, or ALFA. Nicola Romeo bought the company in 1915 and added his name.

Kia

In Korean, the name means “rising from Asia.”

Toyota

Originally called Toyoda, after founder Sakichi Toyoda, the company held a contest to come up with a better name. The winner: Toyota.

Aaston Martin

Lionel Martin started the company in England, near Aston Hill.

Hum-Vee

It’s an approximate pronuncitation of HMMWV—an acronym for “High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle.”

Hyundai

“Modern” in Korean.

Volvo

The Latin word for “I roll” is volvo. But that’s not a reference to the company’s cars: Volvo’s first product was a ball bearing.

SAAB

The Swedish company started in 1937 as Svenska Aeroplan Aktiebolaget, or SAAB for short.

Daihatsu

Was a cheap, compact Daihatsu your first car? In Japanese, dai means “first”; hatsu means “engine.”

Audi

In 1899 August Horch started a car company—he called it Horch (“hark” in German)—but left it in 1909 to start another car company, which he called Audi, Latin for “hark.”

Fiat

It’s an acronym for Fabbrica Italiana Automobil Torino (“Italian Factory of Cars of Turin”).

Rolls Royce

Engineer Frederick Royce built his first car, the Royce, in 1904. In 1906 he partnered with auto dealer Charles Rolls—Royce made the cars, and Rolls was the exclusive sales agent. In 1998 the company was sold to Volkswagen.

Volkswagen

German for “peoples’ car.”

The post appeared first on Trivia Books and Facts | Uncle John's Bathroom Reader.

July 14, 2016

7 Unique Postage Stamps From Around the World

Philately is one of the most popular hobbies around the world. Here are some truly bizarre finds that would be a great addition to any stamp collection.

In 2004, Austria issued stamps bearing the image of a crystal swan—and the image is coated in actual crystals. They were made of paper and then a few real Swarovski crystals were applied with a special, extra-tough glue that can endure mail sorting machines.

Two years earlier, stamp printers in Gibraltar pioneered the art of putting rocks in stamps. In 2002, the country decided to put actual bits of its famous Rock of Gibraltar into postage stamps bearing the landmark’s image. Limestone was bored from the Rock, powdered, and then mixed in with the ink on the stamp.

Brazil began issuing stamps in 2001 that promoted its most famous commodity: coffee. The stamps feature pictures of coffee beans and plants, and they’re also embedded with the smell of coffee. (The aromas stay strong for as long as five years.)

Malaysia has offered a series of stamps depicting some of the exotic animals native to the country, such as the flying fox and the moon rat. Those animals are nocturnal, so to hammer that point home, the eyes on the stamps of those animals glow in the dark.

Bhutan issued stamps in 1973 that were actually tiny, functional records. Played on a turntable, they included recordings of Bhutanese folk songs and stories about the nation’s history.

When you think of Switzerland, do you think of wooden shoes? Think of wooden stamps. In 2004, the nation turned some 120-year-old fir trees into a limited edition of postage stamps made from very, very thin wood.

Switzerland is also famous for Swiss chocolate. Recently he country sold stamps wrapped in foil that when opened resembled a bar of chocolate squares. They look and smell just like chocolate (but when they’re licked they still taste like glue).

The post 7 Unique Postage Stamps From Around the World appeared first on Trivia Books and Facts | Uncle John's Bathroom Reader.

They Come From France

Today is Bastille Day, a holiday that commemorates an important event in the French Revolution. On that note, here are some inventions you may not have known originally came from France.

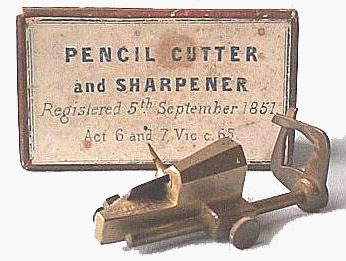

The Pencil Sharpener

A French mathematician named Bernard Lassimonne went through so many pencils that they got dull too fast, and he hated having to sharpen them with a knife. So, in 1828, he filed a French patent for the first ever pencil sharpener. It was a crude design, however, and was much improved upon in 1847 by another French inventor, Thierry des Estivaux. Its his pencil sharpener that’s been the standard ever since.

The Camera Phone

In 1997, still relatively early in the cell phone revolution, the most popular cell phone on the market at the time was the Motorola Startac. It pretty much made phone calls, and that was it. But French software entrepreneur Philippe Kahn had a baby on the way, and he lamented how he wouldn’t have a way to instantly send photos of his newborn—he’s have to take a photo, get it printed out, and then attach it as an email or send it in the mail. Kahn wanted to create “a 21st century version of a Polaroid picture.” So, he bought an early digital camera—a Casio QV-10, and inserted the camera-taking gadgetry into the guts of his Startac. On June 11, 1997, Kahn sent a picture of his new baby, Sophie, to friends’ emails…with his phone. (By the way, the French word for “selfies”? It’s le selfie.)

Mayonnaise

According to legend, that goop you put on your sandwich was supposedly invented to celebrate a French military victory in 1756. The Duke de Richelieu led French forces to capture Port Mahon on the Spanish island of Minorca. The Duke’s private and very discerning chef put together a victory feast for the Duke and his associates, but couldn’t find enough cream for the dish he wanted to make, so he made a cream-like emulsion out of oil and eggs. Since they were in Port Mahon, he named it mahonnaise. Other food historians suggest that the condiment may have originated in the French city of Bayonne, where it was known as bayonnaise.

The post They Come From France appeared first on Trivia Books and Facts | Uncle John's Bathroom Reader.