Dan Thompson's Blog, page 20

July 2, 2012

Should We Just Kill Him?

The big battle has come, our hero is triumphant, and evil has been vanquished. What do we do with the bad guy now? Do we put him in jail, or do we just kill him? I don’t mean this to be a debate over capital punishment. Rather, I’m looking at what satisfies us as readers/viewers. Are we okay with putting the evil genius behind bars to contemplate his wrongdoings, or do we need the hero to plug him through the heart with his double-barreled ray gun?

I think the answer depends on several factors. What kind of villain was he? What kind of hero defeated him? What kind of world are we in, i.e. what are our genre constraints? And heck, to some extent, which direction is the wind blowing?

Let’s start with the villain. Is he a murderer or a financial swindler? If a murderer, was this a single crime of passion or a long series of calculated assassinations? If a swindler, did he go after your grandmother’s savings, or did he take down the Italian economy? And finally, was he an average guy doing bad things, or is he truly some evil genius who will forever seek to show off his capacity for mayhem?

Let’s start with the villain. Is he a murderer or a financial swindler? If a murderer, was this a single crime of passion or a long series of calculated assassinations? If a swindler, did he go after your grandmother’s savings, or did he take down the Italian economy? And finally, was he an average guy doing bad things, or is he truly some evil genius who will forever seek to show off his capacity for mayhem?

As much as I said this wasn’t a debate about capital punishment, many of those same factors enter our literary calculations. If the villain was the guy next door who made a series of bad decisions, we’re more likely to be satisfied with locking him up for a lifetime of remorse. On the other hand, if he’s some sociopath bent on nuclear holocaust, I think we’re a little less satisfied with that plan of remorse. After all, he’s shown that he won’t feel remorse. He’ll just be plotting some other way to unleash Armageddon.

But in addition to things like recidivism and the scale of the crimes, we readers (and the hero) also make the decision based on personal feelings. Did this guy go after the hero’s own grandmother with his ponzi scheme? Was one of the slasher victims our detective’s innocent wife? For God’s sake, did that evil bitch run over my precious little six-legged space kitten?!!

These are things that would get you kicked off a jury faster than… well… I don’t know, because that’s pretty as extreme as it gets judically. We don’t let victims’ friends and families sit in judgment of the accused, but in fiction, this isn’t a jury. Our hero has the chance to be judge, jury, and executioner, and the more personal it gets, the further along that triple role our hero is going to go.

As much as we would never condone it in our real-world judicial system, if the stakes are sufficiently personal most readers find satisfaction in a hero’s righteous revenge. I could argue that this lets us exorcise that particular demon in a safe way, but I don’t think I can argue that the demon isn’t there to begin with. Maybe that’s all hindbrain stuff that we’re trying to evolve our way out of, but for now, both we and our heroes are stuck with it.

As much as we would never condone it in our real-world judicial system, if the stakes are sufficiently personal most readers find satisfaction in a hero’s righteous revenge. I could argue that this lets us exorcise that particular demon in a safe way, but I don’t think I can argue that the demon isn’t there to begin with. Maybe that’s all hindbrain stuff that we’re trying to evolve our way out of, but for now, both we and our heroes are stuck with it.

But not all heroes are wrathful revenge-monkeys with poor impulse control. Take Superman, for example. I’m not a huge comic collector, so I can’t speak to the eighty years of pulp canon, but from the movies and the old black-and-white TV shows, I don’t think I ever saw him kill anyone. For starters, he’s just a little too pure to kill anyone, or at least, too pure to act in vengeful anger. But also, he’s Superman. If the bad guy gets out, unleashes mayhem again, Superman can just throw him in prison again. Sure, some people get hurt along the way, but Superman’s hands are still clean.

But not all heroes are wrathful revenge-monkeys with poor impulse control. Take Superman, for example. I’m not a huge comic collector, so I can’t speak to the eighty years of pulp canon, but from the movies and the old black-and-white TV shows, I don’t think I ever saw him kill anyone. For starters, he’s just a little too pure to kill anyone, or at least, too pure to act in vengeful anger. But also, he’s Superman. If the bad guy gets out, unleashes mayhem again, Superman can just throw him in prison again. Sure, some people get hurt along the way, but Superman’s hands are still clean.

Other heroes are happy to mete out vengeful justice on their own. Dirty Harry is a great example of this, particularly in the very first film. He has no qualms about killing the bad guy, and he’s got a 44 Magnum loaded with righteous wrath. However, as much as he is held up as the quintessential anti-hero, he still follows at least one rule. He won’t kill a defenseless criminal. That’s the deal with his whole “Do you feel lucky?” speech. He wants the bad guy to pick up his weapon to make him a legitimate target.

Other heroes are happy to mete out vengeful justice on their own. Dirty Harry is a great example of this, particularly in the very first film. He has no qualms about killing the bad guy, and he’s got a 44 Magnum loaded with righteous wrath. However, as much as he is held up as the quintessential anti-hero, he still follows at least one rule. He won’t kill a defenseless criminal. That’s the deal with his whole “Do you feel lucky?” speech. He wants the bad guy to pick up his weapon to make him a legitimate target.

That particular bit of rule-following is endemic in another type of hero, who would like to consider himself as pure as Superman but is still willing to kill. This is the hero who defeats that bad guy and then walks away, only to have the bad guy rise from the debris to take one last shot at the hero. The hero, of course, puts the bad guy down for good, usually with an unquestionably lethal act that is accomplished with trivial effort, e.g. the gunshot precisely between the eyes from fifty feet. [As a side note, when putting down your bad guys, ALWAYS double-tap. Really, I think we’ve all been burned by this enough to know that we’re not done until the double-tap.]

But then you have some heroes who are unapologetically dishing out a chilled plate of revenge. I think of the original Mad Max where Max puts some guys behind bars for killing his partner, only to have them be let out and suffer an even greater, personal loss. The revenge orgy that ensues is enough to satisfy any grudge-meister, especially the final act of revenge. He shows no hesitation, no remorse, and absolutely no sympathy for the soon-to-be-dead bad guy. I won’t say that Max will go ape-shit if you cheat him at cards, but this is a guy that you don’t want to leave around for Act II if you can help it.

But then you have some heroes who are unapologetically dishing out a chilled plate of revenge. I think of the original Mad Max where Max puts some guys behind bars for killing his partner, only to have them be let out and suffer an even greater, personal loss. The revenge orgy that ensues is enough to satisfy any grudge-meister, especially the final act of revenge. He shows no hesitation, no remorse, and absolutely no sympathy for the soon-to-be-dead bad guy. I won’t say that Max will go ape-shit if you cheat him at cards, but this is a guy that you don’t want to leave around for Act II if you can help it.

But then there’s the world around you. The Max in that last example was living out on the frontier of the Australian outback in a time that was either during or shortly after some apocalyptic war. The remnants of civilized society weren’t working anymore, and Max had a certain amount of freedom to hunt these people down. Score one for the genre, because after the apocalypse, it’s an all-you-can-eat revenge-flavored ice cream buffet.

Compare that to Superman’s world of Metropolis. The government is stable and happy to lock up these troublemakers, if only it was strong enough to catch them. Gee thanks, Superman! I mean, it’s kind of hard to argue against incarceration there. He caught them in the act, gathered up the evidence with his free hand, and to top it off, Superman makes a great eye-witness for the prosecution. (And to top it off, Lois poisoned the whole jury pool with an exclusive article.)

Dirty Harry (and Batman for that matter) split the difference. There’s still a functioning judicial system, but it’s imperfect and apparently growing worse. We’d like to put these bad guys away, but we realize that in this particular case, we just can’t trust that the system will work. Even then, they sometimes drop the villains off at the local precinct.

But there are also genre constraints that limit the hero even more than the judicial backdrop. Action films pretty much require the villain’s death, the more spectacular the better. Even beloved villains like Hans Gruber have to take the plunge. Meanwhile, some comic stories/films require that the evil genius live to escape and fight another day. Mysteries almost always require that the villain survive because the detective has to win by intellect, not by force. Even if he proves the villain’s guilt first, it’s somehow dissatisfying if that wasn’t enough, that some additional low-brow gunplay was required to be victorious.

Finally, I’d say that the political winds of the real world effect how we and the heroes see this. In the early years of the “War on Terror” in the US, I noticed a lot less sympathy for villains, and more and more heroes did “what had to be done.” This was also true in the late 70’s through 80’s as we experienced pushback from the peace-movement 60’s and ratcheted up the cold war with the Soviets. But in the 90’s and increasingly now in the 2010’s, I saw a lot more heroes going with the equivalent of Hawaii 5-O’s “Book ‘em Danno”.

It would seem that there are times when the unruly mob is giving a collective thumbs down, chanting “death, death” to the hapless gladiators in the arena, and sometimes we’re in a more forgiving mood. It’s easier to fine-tune that in movies which can be more timely with their audience, but it can leave some books out of step as they can find “fresh readers” twenty or thirty years later.

It would seem that there are times when the unruly mob is giving a collective thumbs down, chanting “death, death” to the hapless gladiators in the arena, and sometimes we’re in a more forgiving mood. It’s easier to fine-tune that in movies which can be more timely with their audience, but it can leave some books out of step as they can find “fresh readers” twenty or thirty years later.

So, how about you guys? What villain were you glad to see splattered? Which ones got the mercy they deserved? And which ones got away or were unfairly squished?

June 25, 2012

DARPA’s 100-year Starship Program

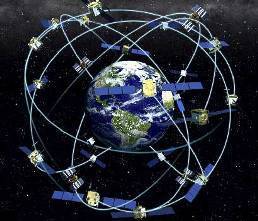

I spent the weekend down in Houston for ApolloCon, and the most surprising panel I attended was on a DARPA program to lay down the research necessary to launch an interstellar ship a hundred years from now. To quote from their announcement last year:

In 1865, Jules Verne put forward a seemingly impossible notion in From Earth to the Moon: he wrote about building a giant space gun that would rocket men to the moon. Just over a century later, the impossible became reality when Neil Armstrong took that first step onto the moon’s surface in 1969.

A century can fundamentally change our understanding of our universe and reality. Man’s desire to explore space and achieve the seemingly impossible is at the center of the 100 Year Starship Study Symposium. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and NASA Ames Research Center (serving as execution agent), are working together to convene thought leaders dealing with the practical and fantastic issues man needs to address to achieve interstellar flight one hundred years from now.

They’re not handing out research grants at the moment, but they hosted a symposium last fall to talk about issues from propulsion to philosophy, i.e. not just how to get there, but why we should go. This year, they kicked off the seed funding to create a private organization called the 100 Year Starship. They’re holding another symposium this September in Houston. Given that it’s just a few hours’ drive for me, I’m seriously thinking about it.

I mean, really, this is seriously cranking my geek. Or… you know, something that sounds maybe a little less disturbing.

June 22, 2012

Review: Intruder, by C.J. Cherryh

This is the thirteenth book in her Foreigner series about Bren Cameron on the world of the Atevi.

I had been waiting eagerly for this one for a while since it seemed to have had a long gap since the last one. I had also been eagerly looking forward to the start of another trilogy-set in this series. However, I have to say I’m a little disappointed in this one, though it’s not really the fault of the book.

I had been waiting eagerly for this one for a while since it seemed to have had a long gap since the last one. I had also been eagerly looking forward to the start of another trilogy-set in this series. However, I have to say I’m a little disappointed in this one, though it’s not really the fault of the book.

I love this series for three reasons: 1) Cherryh’s use of language is fantastic, both in her English narrative as well as her English-rendition of the Ragi language, 2) her exploration of the mixed psychologies of human and alien (Atevi) and the political problems they generate has been fascinating, and 3) the stakes have always been high with the political ramification reaching out from the quaint villages into interstellar space.

The first trilogy developed the world and hinted at the interstellar politics that were about to crash down on them. The second trilogy had Bren going out to face those politics and solve them. The third trilogy dealt with the fallout of what happened while he was gone. The fourth trilogy dealt with more fallout from the time they were gone. And… you guessed it, this fifth trilogy opens with even more fallout from the time they were gone.

All the while there is another bit of interstellar politics looming over their heads, with its promised arrival date any day now.

Or more to the point, any book now.

So I was really expecting this trilogy to open with the resurgence of the interstellar problem that was left open during the second trilogy. And MINI-SPOILER, it didn’t. In fact, so strong was my expectation that I went through most of the book expecting it to pop up at the most inconvenient moment, or at the very least, at the end in a sort of cliff-hanger/teaser for the next book. But it didn’t.

Yes, the political intrigue was suspenseful, and I’m really enjoying the growing relationship between Tabini (essentially the king) and his young son Cajeiri. I’m also intrigued by the increasingly visible fractures in the ever-secretive Assassin’s Guild, and I really like what it’s showing us about the back stories of Bren’s bodyguards.

But this is the seventh book in a row dealing with the political fallout of what happened when Bren was away in space. How many more will there be before we get back to that looming interstellar crisis? I feel a bit like I’m complimenting an endless line of chicken dishes, all the while craving another taste of beef.

And yet it was good, so I can’t really fault it for dashing my own expectations. So, I’m giving it a qualified thumbs-up.

June 18, 2012

Better Sequels

Usually sequels don’t live up to the original, but sometimes they surpass it. I was talking to a friend recently, trying to come up with a list of them, but it was hard. What made it harder was that I wanted to limit it to SF/F genre films. We came up with three, and I found a few more. We also found several that were debateable or didn’t quite make it. Here we go:

The Winners:

The Empire Strikes Back: This one is so often quoted as the declining-sequel rule breaker that it has to go on the list, and I think it really does deserve it. As much as I loved Star Wars as a kid, Empire turned the franchise – ever so briefly – into more serious adult fare.

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan: This one gets in easily, not only because it was a great film, but because the original Star Trek: The Motion Picture was so limp that it’s a miracle this one was ever made. In my not so humble opinion, this film saved the franchise.

Star Trek: First Contact: I was tempted to knock this one out, because it’s not technically a sequel as much as it’s the next installment in an ongoing series. However, I can buy the argument that Star Trek: Generations started off a new film sequence, and that let’s this one in. So, while Generations tried to do far too much and didn’t pull much of it off, First Contact focused on one thing: stopping the Borg from destroying our history. It had a tight story, cool characters, and plus… you know… THE BORG!

Road Warrior: Some people don’t even realize this is a sequel, but the original Mad Max was an Australian blockbuster. I love it – and would love it even more without the terrible dubbing job – but I have to say that Road Warrior has a better style, better car chases, and a better plot.

Aliens: My friend argued against this one, not because he thought the original Alien was better but because they were so different as to almost be different genres. Alien is a walk through a dark alley, almost a horror film, while Aliens is a military-action rollercoaster. But I think they’re close enough that I’m going to include it.

Now on the many Honorable Mentions:

For a Few Dollars More: This is well outside the bounds by genre since it’s a western. It’s also questionable whether it’s even a sequel to Fistful of Dollars. However, it is the second in what most folks refer to as “the Man with No Name” trilogy that ends with the classic The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. In some ways, this one was the high point of the trilogy for me, and Clint Eastwood almost played second fiddle to Lee Van Cleef’s search for long-delayed justice for a very personal crime. If you’re a fan of gun-fighting westerns, you need to see this one.

The Four Musketeers: This is historical fiction as opposed to SF/F fiction, but the main reason I don’t like seeing it on lists of great sequels is that it’s not really a sequel. It’s the second half of the Three Musketeers movie that was released the year before. The director shot so much film that he decided to break it up, leaving quite the legal mess for the film industry to sort out in contract law for generations to come. However, all that aside, this is a fabulous film, and this pair of Musketeer films (with a young Michael York) is in my opinion the best of all the Musketeer tellings.

Kill Bill, Vol 2: This one also shows up on great sequel lists, but I also don’t think it belongs for the same reason that The Four Musketeers didn’t belong. It’s not a sequel. It’s the second half of the film, and of course it’s better than “the original”. It has the climax, you dummy. But yeah, great film. The first one ripped out your carotid in a nasty arterial spray, but the second one grabbed on tight and yanked your heart out through your severed neck. Ok, not that bloody, but you get the idea.

Spider-Man 2 and The Dark Knight: I think that both of these sequels were better than the originals, but despite all the fancy weapons and cool gadgets, I don’t consider comic movies to be either science fiction or fantasy. I think they’re their own genre like horror or mystery.

Toy Story 2: The original was awesome, but this sequel knocked it out of the park. I just don’t think it qualifies as SF/F.

Terminator 2: My friend lobbied hard for this one, but personally, I think the original is still the best of the series. Yes, the second one had better effects and a pretty good story, but the original one hangs together so much better and has that wonderful bittersweet romance.

Superman 2: Some people rate this one as being better than the original, and given the stupid fly-around-the-earth-backwards time travel in the first film, I can see their argument. However, the people making this argument are usually referring to the Donner cut of the film rather than the theatrical release, and I haven’t seen the Donner cut. If I do, I might join their camp, but in the meantime, I’m sticking with the origin-heavy original. But yeah, it’s still comic, not SF.

So, what great sequels did I miss? What about book sequels instead of movie sequels? Or for that matter, does this make you think of any terrible sequels? I’ve got half a mind to follow this up with a list of sequels so bad that they don’t officially exist, e.g. Highlander II or Star Trek V.

June 15, 2012

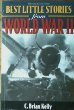

Review: Best Little Stories from World War II, by C. Brian Kelly

I’ve been working through this one for a few months now:

This is a collection of short articles about World War II, centered on the little picture, i.e. small actions, little anecdotes, surprising details. I usually enjoy reading this kind of thing, and I do have a strong interest in World War II. However, I can’t honestly recommend this one.

This is a collection of short articles about World War II, centered on the little picture, i.e. small actions, little anecdotes, surprising details. I usually enjoy reading this kind of thing, and I do have a strong interest in World War II. However, I can’t honestly recommend this one.

The content was okay, but what really annoyed was the variation in style. The articles were not written by Kelly. Rather, he edited them together from multiple sources, and the variation in style comes from the multitude of original sources. Some are bare-boned factual accounts. Others are breathless reports from the front line. Some are almost propaganda. And some are trying too hard to obscure the facts for cuteness sake, all so that they can end with, “And that soldier went on to be Dwight D. Eisenhower,” or some such.

Coming after “Band of Brothers” by Ambrose, the inconsistent voice and (in some cases) poor writing in this book was a big disappointment.

June 13, 2012

Why I Don’t Talk About WIP

That’s W-I-P, Work In Progress, not WHIP (Wicked Handled Instrument of Punishment?), and I don’t talk about work in progress. I used to, a long time back, but not anymore. Why? Well, that’s something I will talk about.

First of all, I must say that the temptation to talk about a work in progress is strong. Writing is fun. It’s the grown-up equivalent of playing make-believe. You know what’s even more fun? Talking about fun stuff with other people, and I used to indulge myself in it quite a bit. However, after a while, talking about it stopped being fun and started to become frustrating – so frustrating, in fact, that not only did I stop talking about writing, but I stopped writing.

I started up again, eventually, but I rarely spoke of it. Very specifically, I never talked about the thing I was writing, but it wasn’t until about five years ago that I really nailed down my reasons for it. So here they are:

Reason #1: It’s my story, not yours.

This was one of the most annoying things that would happen when I talked about a story I was writing. I would be describing the basic setup or plot, and the person I was talking to would jump in with some suggestion. “Wouldn’t it be cool if that character had some kind of superpower?” Or maybe, “That would work really well if it turns out to be a big government conspiracy.” And of course, “We should later find out that the bad guy is really his father!”

This was one of the most annoying things that would happen when I talked about a story I was writing. I would be describing the basic setup or plot, and the person I was talking to would jump in with some suggestion. “Wouldn’t it be cool if that character had some kind of superpower?” Or maybe, “That would work really well if it turns out to be a big government conspiracy.” And of course, “We should later find out that the bad guy is really his father!”

I appreciate the energy. Really, I do. I hear ideas, and I go spinning off in my own direction. I see little situations and start twisting them into epic struggles and ancient prophecies. I know what’s going on in your head when you come back with that twist on the story I’m talking about. I get it, ok?

But no, it would not be cool if that character had a superpower, or was part of a government conspiracy, or turned out to be the hero’s father. It’s not that those are bad ideas. I’m sure they could be turned into great stories, but they’re not MY story. In MY story, that character is our heroes trusted sidekick, and the government is generally clueless and unable to help, and our hero’s father died tragically in his son’s arms in chapter 1.

THAT is the story I’m trying to tell. THAT is the story I have passion for. If you have the same passion for your father and son team of superhero conspiracy fighters, I say go for it. Put your butt in the chair and crank that puppy out. It’s fun. Really.

Unfortunately, most people didn’t actually want to do that. They wanted me to do that, and when I wouldn’t produce “Jorel and Superman vs. the Trilateral Commission”, they got kind of pissy with me. And that, ladies and gentlemen, was NOT fun.

Reason #2: No, it’s not just like that other thing you read.

This was not as frustrating as that first one, but it was much more disheartening. I would describe an idea, and people would say, “Yeah, that’s just like this book I read last spring.” Sometimes it would be something I’d never heard of, and sometimes it would be something I was already familiar with.

This was not as frustrating as that first one, but it was much more disheartening. I would describe an idea, and people would say, “Yeah, that’s just like this book I read last spring.” Sometimes it would be something I’d never heard of, and sometimes it would be something I was already familiar with.

If I’d never heard of it, I would often get sidetracked for a while as I chased down that other story and read it, only to discover that no, it was not the same as my idea. Yes, both stories had dirigibles, but yours is a steampunk romance, while mine refights the battle of Troy by time-travelling aeronauts in a NASA project gone awry.

And if it was something I had heard of, then the conversation immediately segued into an argument about how it was different. “Sure, it’s Troy instead of Paris, but there was a guy named Paris in Troy, and we all know about the romance between Paris and Helen. And of course, the dirigible is the key!”

But they’re not the same. I’ve heard arguments that there are only N plots or conflicts, ranging from one to twenty-seven. (FWIW, the “one story” is kind of two: local boy goes off to have adventure, or a stranger comes to town. It’s just a choice of which side of the story you’re on.) And, so these arguments go, the only thing authors can do is bring their particular voice to the tale.Maybe, but that particular voice makes all the difference in the world.

Compare the two takes on Battlestar Galactica, one from the 1970’s and one from the 2000’s. Look at all they had in common: the same genesis of holocaust, the same goal to find Earth, most of the same characters, ships, and so on. But in execution they were so incredibly different. I look at that as proof that you could give two authors the same idea – hell, maybe even the same outline – and get two radically different stories.

And yet, every comparison came as a nasty jab in my side telling me, “You have no original ideas. You should just give up.” And so, eventually, I did.

Reason #3: I can only tell the story once.

That’s an exaggeration, but there’s an element of truth. For me, once a story takes root in my mind, it burns with an all-consuming passion until I can get it out. It’s always there, demanding to be let loose. People sometimes talk about gifts from their muse, but for me, my muse is a torturous bitch keeping me awake at night and haunting my days.

That’s an exaggeration, but there’s an element of truth. For me, once a story takes root in my mind, it burns with an all-consuming passion until I can get it out. It’s always there, demanding to be let loose. People sometimes talk about gifts from their muse, but for me, my muse is a torturous bitch keeping me awake at night and haunting my days.

Now, I can tell someone about the idea, and that lets the idea out some. It gives me a bit of relief. If I do it often enough, the fire is quenched, and the burning passion to write the story goes away. But then I don’t have a story.

This was crystallized for me when watching the movie Grand Canyon. Steve Martin’s character has had a life-changing revelation, but he doesn’t want to tell his friend about it. When pressured to tell him, he replies, “No, I don’t want to talk about it. Sometimes I think people talk about doing things as a substitute for actually doing them.”

Yep, he nailed it. Instead of writing the stories, I was talking about them, and every time I opened my mouth about a story, I was spending my passion for it until eventually there was no passion left. This, more than any other reason, was why I stopped talking about work in progress. Now, instead of talking about stories, I write them.

So, what do I say when someone asks what the story is about?

In most situations, it’s not feasible to quote this essay at them. Sometimes I’ll throw the Grand Canyon quote at them and go on from there, but usually it’s just a mild inquiry. They’re not prepared for me open the fire hose of creative theory on them.

So instead, I’ve developed a series of uninformative and somewhat off-putting code phrases. The first novel I used this technique with was “about lesbian robots.” It raised a few eyebrows, but I never got any follow-up questions.

You might think the answer is a lie, but it has core element of truth to it. It was really a Pinocchio story about an android trying to become sufficiently self-aware and independent so as to be the android equivalent of “a real boy.” It just so happened that she was styled as a female android, and her initial act of becoming self-aware was the realization that she had been in love with her former owner, a woman. Hence, lesbian robots.

The story that became my novel Beneath the Sky was described to friends as “about the Mayflower vs. a 747.” Certainly there were no pilgrim sailing ships or jumbo jets in the book, but it was true enough to show up (in modified form) in the blurb on the back cover.

Some other projects in the pipeline include, “a boy playing with Daddy’s ships,” “a reporter who goes to Hell,” and “learning chess from a dead man.” Later in the year, I hope to get started on “falling rocks”.

So if you ever hear one of these, it’s not me disrespecting you. It’s me making sure that the story gets onto the page and into your hands.

June 11, 2012

Exploring the Final Frontier on a Schedule

In the first two installments of this series, I looked at exploring a new star system and examining a planet from orbit. Depending on the level of detail you want, this could take a few days to a few years… for each planet. With 15,000 star systems to explore within 100 light years from Earth, how are we going to do this in a reasonable amount of time, even with our nifty FTL survey ships?

I think the best solution is to parallelize as much as possible. That is, throw more manpower at it, or in this case, more ship-power. Since it takes some number of orbits around a planet to map it with the desired detail, the best way to speed that up is to do multiple orbits at once by employing satellites rather than simply orbit in the ship.

Such satellites would not need independent launch systems. The ship could assume the desired orbit, lower the satellite out of a cargo bay, and gently move off towards the next desired orbit. That way, something that would have taken a few days could be done in one.

Such satellites would not need independent launch systems. The ship could assume the desired orbit, lower the satellite out of a cargo bay, and gently move off towards the next desired orbit. That way, something that would have taken a few days could be done in one.

Alternatively, if a particular system has more than one planet (or moon) in need of such mapping, a portion of the satellites could be deployed at one world, left to do their survey, while the ship goes to another world to deploy more of the satellites. In our solar system, this would be the equivalent of populating Earth’s orbit with observation satellites, popping over to Mars in mere moments using your nifty FTL drive to seed it with satellites. You might even dash out to Jupiter to set one around Europa. By the time you had set all that up, it would be time to swing back to Earth to collect your satellites and their data.

In fact, if one world in particular deserved a longer, high-resolution look, then one or more satellites could be left in place while the ship moves on to another star system entirely. It could then come back after a few months and collect a wealth of information. This would be useful if you saw signs of life or hints of artificial constructs on the ground and wanted to get that 1-meter resolution scan, or perhaps even zoom in further on the really interesting spots. I would not propose to attempt reading the New Rigel Times over someone’s shoulder, but you might discover that he did, in fact, have a shoulder to begin with.

How many satellites should the ship carry? All I have is a gut feeling for bringing about a dozen. It would be great to have hundreds, but when you start thinking about the big optical lenses, these satellites are bulky. A dozen should not take up an unreasonable amount of room, and it gives the survey crew enough to check out multiple planets at once as well as a few to leave behind without impairing the rest of the survey mission.

I would also want to carry along a number of communication satellites to be left in key locations. If my FTL communication system requires boosters or relays, it would make sense to leave them near interesting worlds, technology willing. And if the FTL communication is via courier ships, then these message queue satellites should be left at predictable locations, i.e. around promising stars near planets in the habitable zones. Hopefully, these could be of a reasonable size. It would be nice to leave one in every star system visited, but failing that, it would be nice to leave behind five or ten.

So how long will this take? I think with the extra satellites, a star system could get a decent exploration in about five days. For convenience, I’m going to assume an FTL speed of about one light year per day, and say that we can get from one system to the next in an average of five days. Yes, the distance varies from 10 light years for solitary stars to less than one for places like the Pleiades, but we’re into hand-waving territory here. This might take even longer when you considering the problems of efficient routing (i.e. the travelling salesman problem) and the inevitable backtracking to pick up any satellites we left behind, slowing us down just a little more. Then again, there’s nothing to stop me from waving my hands again and saying two light years per day. So let’s stick with five days travel between stars.

So, put those together, and you can explore a new star system every 10 days, and I think that’s pretty optimistic.

But how long will you explore? I’m going to use the U.S. Navy as a guide, and while ship deployment lengths vary, few are longer than six months at a time. Some of this is supplies. Some of it is wear and tear on the equipment (being as sea is kind of rough on things). But I think a lot of it is simply the limits of the human psyche. While visiting Alexandria, Hong Kong, or Rio de Janeiro can ease the stress, the real test would be those guys riding it out alone on the nuclear subs, and I believe their tours are no more than six months.

But how long will you explore? I’m going to use the U.S. Navy as a guide, and while ship deployment lengths vary, few are longer than six months at a time. Some of this is supplies. Some of it is wear and tear on the equipment (being as sea is kind of rough on things). But I think a lot of it is simply the limits of the human psyche. While visiting Alexandria, Hong Kong, or Rio de Janeiro can ease the stress, the real test would be those guys riding it out alone on the nuclear subs, and I believe their tours are no more than six months.

So is that six months of survey? Well, sure, as long as we’re only exploring the neighborhood right nearby, but as time goes by, we’ll be exploring further and further afield. Even at a light-year per day, we could spend three months getting out to those worlds in the 90-100ly range only to have to turn around and come back home.

So I’m going to assume that as the project progresses, we build up some forward bases. In fact, one of jobs of this survey would be to find good locations for those forward bases. Some of those more interesting worlds could be candidates for terraforming and eventual colonization. Building a meeting place for crews to get a little rest, repairs, and crew rotation would be a decent place to start with such an effort. Welcome to Deepspace-84.

So, I’ll assume that for the duration of the project, the survey area for a particular six month tour is roughly 30 days from a forward base. Furthermore, I’m going to give them two months of downtime back at that base. Ships will need maintenance, resupply, upgrades, and so on. Plus, it gives them some leeway in their schedule if they run a little behind.

After setting aside 60 days to get to and from the survey area, that leaves us with about 120 days to survey, and at ten days per star system, that’s only twelve new star systems. Add in the two months of downtime between survey missions, and that’s twelve new star systems per eight months. Since we’ll certainly be having more than one ship doing this, let’s average it out to only eighteen star systems per ship-year.

Now, how many stars were we talking about? Oh yeah, 15,000 stars within 100 light years. At the survey rate I’ve given, that’s about 830 ship-years worth of survey. If we want to do this in as little as twenty years, that means about 42 survey ships. Maybe even bump that up to fifty for some inevitable problems that we’ll run into along the way.

Now, how many stars were we talking about? Oh yeah, 15,000 stars within 100 light years. At the survey rate I’ve given, that’s about 830 ship-years worth of survey. If we want to do this in as little as twenty years, that means about 42 survey ships. Maybe even bump that up to fifty for some inevitable problems that we’ll run into along the way.

Considering that the U.S. Navy has varied from 250-600 ocean-going ships over the last century, fifty ships does not seem an unreasonable number of ships to dedicate to such an effort. I’ve been imagining these ships as being fairly lightly crewed by naval standards, requiring probably only forty to one hundred crew each, but that’s still a few thousand crew.

But even 5000 is not that many people, especially considering the number of Earthbound explorers who would be dying for a chance at it. I know I would be eager to put in my resume. Even if I don’t get in on this one, I might still have a shot at the next phase of scoping out the 100,000 stars in the next 100 light years out from there.

Wouldn’t you want to spend a few years of your life on something like this?

June 6, 2012

Sequel Summary Syndrome

So I’m writing a sequel now. No, it’s not a sequel to Beneath the Sky. It’s the sequel to another book of mine that’s scampering along towards publication. Anyway, this has brought me face to page with one of the most annoying things about sequels. How do you remind old readers (and tell new readers) what happened in the previous book without boring them to tears?

We have all seen this done badly. We will get pages of exposition dumped between trivial dialog, or worse, masquerading as dialog. “Well, Bob, as you know, I recently went on a two-year expedition up the Nile with my partner James, who unbeknownst to me, was actually a secret agent working in the Queen’s private service, but we were both equally surprised when the villainous Dr. Cavendale made his appearance in chapter four, I mean, in Alexandria. I need not tell you what happened next, but it began with…”

When I see it done that badly, I just want to skip ahead to the third or fourth chapter. Sure, I might miss something important, but if so, surely it will be repeated at the start of the next book. If I ever live long enough to get through this one, that is.

There has to be a better way.

I confess that in a fit of disgust with one particular author, I thought that the best solution would be a simple prologue. No, not the kind of prologue that shows a shadowy figure clawing through the Cave of Obscuria in the Time Before Calendars. No, I mean one that simply says, “This is book three in the series. If you’re not going to read the others first or if you’ve merely forgotten what happened in them, well, here’s what happened. In book 1, Billy met a nanobot named Charlie…” Two or three pages of key plot points, and then you can dive right into the new story.

But when I shared this with other readers, no one really like it much. To tell you the truth, I have soured on it some myself. I’m pretty sure I would skip those prologues, and then I would get into chapter three and start wondering where the hell Midge the Motor-mixer came from, because she walked onto the page like she owned the place.

So what are writers supposed to do? Fortunately, I’ve seen it done better recently, and once again I’ll point to Jim Butcher, that dream-crushing bastard of good writing. (No, I’m not envious of his talent – why do you ask?) I never get that mind-numbing “as you recall” crap from him, especially not from Harry Dresden. In fact, he doesn’t seem to reference the past much at all.

Then how I know where Midge the Motor-mixing Magi came from?

The key seems to be to put off all that backstory information until you absolutely need it, and then give the least information possible. From my programming days, that was what we called demand-loading. Don’t load the code until you actually call it the first time.

The only problem with this solution is that… well, it’s HARD. You can’t have Midge barge dramatically into the room and then dump three pages of backstory on the reader. By the time we get to the end, we’ve forgotten what she’s doing right now, and given that she’s mixing up people’s motorheads, it’s kind of important. I suppose the coding equivalent of that would be to demand-load a 200MB subsystem just to display a dialog. By the time it comes up.

Here I have to say Mr. Butcher cheats a little, but it’s a cheat I wish more people used. In Harry’s first-person narrative, he drops it in as a friendly reminder to the reader who obviously remembers all the rest, right? Instead of three pages of backstory, it’s merely, “Midge the Maddening Motor-Mixing Mage barged through the door. Damn, but I hadn’t seen her since that little disagreement we had over farm equipment. Nebraska is still putting out that fire.” Boom, we know she’s an enemy, they already fought once, and there’s unfinished business, and oh yeah… farm equipment. That was in book 16, Hay Day. I remember now.

It’s harder in third person, where the narrative voice is a lot stiffer, but still, I get how it’s supposed to be done. That doesn’t mean I know how to actually do it. If that doesn’t make sense, watch me try to change the oil on my car sometime. I mean, really, you just unscrew this little filter thing, right?

So, what was the worst sequel summary you ever saw?

June 4, 2012

Exploring the Final Frontier from Orbit

A couple of weeks back, we set forth in our sparkly new FTL survey ship to explore the 15,000 star systems within 100 light years of Earth. We hopped around a particular system to track down any planets it might have, and now we’re going to take a closer look at them. While it would be fun to zap down to the surface to get hands-on information, our mission really is survey. Let’s find the interesting places and let some other poor schmuck get fitted for a red shirt.

So what can we do from orbit?

In a lot of ways, this is a question for the CIA, or more accurately the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), the agency in charge of the various US spy satellites. Most of us think of spy satellites as peeking in on missile complexes or uranium enrichment plants, but at a lower resolution, they are quite useful for map-making.

And that gets right to the heart of the matter: resolution vs. coverage area. The optical sensor in your orbital platform is of some fixed size. Maybe it’s ten centimeters or a full meter, but the key is that it’s a fixed number of pixels across, perhaps a hundred thousand. If your optical lenses project an image that represents a square kilometer on the ground, your resolution would be one hundred thousandth of a kilometer, i.e. a centimeter.

While centimeter resolution might thrill the NRO, it’s wasted on us for survey purposes, and the Earth would require at least 500 million of those snapshots. If we had that large of a sensor, we would be much better off taking snapshots of 100km by 100km and getting 1 meter resolution.

You can play around with this a little by taking pictures of things not directly beneath you but scanning east to west and patching them together, but doing it quickly (that is, at orbital speeds) could get quite complicated. I don’t know if our current spy satellites can manage that kind of east-west scanning, or if they simply have to pick their targets more carefully.

In addition to visible-light photography, we can take photographs at varying resolutions in the infrared and ultraviolet. Add in a RADAR transmitter, and we can do terrain height mapping as we fly over.

But how long does this take? Let’s assume a planet the size of the Earth. We do our observations from a polar orbit, taking 100km-wide swaths of photographs as we go. We’ll get lots of overlap near the poles, but we have to make enough passes to cover the entire equator in 100km chunks. At 40,000km around, that’s 400 passes. Orbit times depend on the mass of the planet and the height of the orbit, and on earth we see orbits range from 92 minutes (on the International Space Station) to 27 days (the moon).

But the Earth spins, and since that’s helpful, let’s hope our new planet does too. After 92 minutes, the equatorial land we pass over on the day-side is 2500km from the last picture we took. It would be nicer if it had only moved 100km, but we can work with that. If we choose our orbital altitude correctly, we can get our orbital period to line up so that we’re always hitting some multiple of 100km from the last pass, and with the right rhythm, we’ll keep hitting fresh bits of the equator. It’s one of those prime factor things, cycling over 400 swaths by 3’s (or 7’s, 11’s, 13’s, etc.) will keep hitting new swaths.

We may as well photograph things on the night side as well to capture any surprises like city lights, but we’ll mostly want the daylight side. So that’s 400 orbits of 90 minutes or more, which will take at least 25 days. It would take longer if we want higher resolution, or be done quicker if we settle for lower resolution. Notably, that centimeter resolution could take years, while backing off to 10m resolution could get the job done in a few days. Oh, and then there might be weather getting in your way.

See what I mean about the quandary of coverage vs. resolution? When flying over some of the overlapped areas away from the equator, you can squeeze in some zoomed shots of the more interesting bits, but your overall schedule is going to push your towards the lower resolution. With 15,000 star systems to get to, it’s going to be a hard argument to push for something greater than 10m resolution.

But what can we do to fit more into our schedule? I’ll be talking about that next week when I go after some of the logistics to make this survey project more feasible. Or maybe I’ll just see how mammoth it really is. Either way, I’m still wallowing in wish fulfillment, eager to don my Survey uniform.

May 29, 2012

Back from Flipside

I’m back from Flipside, my annual trek out into the heat of Central Texas for a wild weekend of art, Rangering, sunburn, and the occasional bit of whiskey. I’d actually had some notion that I would get the next column on exploring new solar systems written while I was out there, but that didn’t happen. Clearly I had some kind of temporary insanity to have forgotten just how insane it gets at Flipside. So instead of that, I give you a few highlights from that crazy weekend in the woods.

I airbrushed about a dozen people, including a few of my signature feather jobs, some leopard spots, a full-torso tiger, and some surprisingly good dragon scales. I was very happy with that last one, not only because it came out so well on my first attempt, but because it turned out that the girl I painted them on was the same girl who inspired me to learn the airbrush eight years ago. Back then she was on her honeymoon, and I saw her being painted as a leopard, and it looked so cool I decided I wanted to learn how to do that. This time she was having her eighth anniversary, and I gave her dragon scales.

I also did some Rangering. For the uninitiated, Rangers are volunteer mediators and part of the safety crew. We walk around and look for safety problems. We mediate conflicts. We look out for people who might be in trouble. We do a lot of things you might think cops do, except that we’re not cops. We don’t actually enforce anything. The folks who run the event can enforce something, but about all we do is remind people what they agreed to when they arrived. So I did one and half “dirt” shifts with all the walking around that this implies, finished off my shift-lead training with an “assistant Khaki” shift, and then did my first solo “Khaki” shift as the shift-lead on Sunday morning.

The effigy burn was fabulous. It was an almost fortress-like tower with winged figures gracing all four sides, but when it burned, it took on the look of a flaming chalice and later a flaming horned mask. And then it all came down, nice and safe. My compliments to the build team. On a more personal note, I spread the ashes of another author in the effigy on the morning of the burn. She was a long-time Flipside attendee, and I think she would have liked that.

Physically, I came through it pretty well. I kept my sunburn to a minimum, really only getting one spot on my shoulder that I missed with the sunscreen. I kept sufficiently hydrated and cool, and I actually ate pretty well. Probably the worst I got were some very sore knees from all the walking and a pretty serious case of sleep deprivation. I was getting those droopy, unfocused eyes on the final drive back into civilization, so I promptly did a face-plant onto the sofa as soon as I arrived. Eventually, I got a shower and slipped into bed for a proper rest.

I also had a lot of fun hanging out with my wife and many of our friends. Those are tales probably best left at Flipside, but I did want to give a shout out to the folks at Purple Taco and at KFLIP. Also, doing my shift-lead work in Rangers, I got to see more of the work of the event organizers as they did their best to balance the desire for individual expression vs. the need for community safety. With all the flame-cannons and marauding tree-houses wandering the event, it’s a tough job. My hat is off to them.

I will say, though, that probably my biggest surprise of the weekend was running into people who were reading my book, Beneath the Sky. After doing the launch at the beginning of May, I had split my focus between working on the next book and preparing for Flipside, so I had mostly put that one out of my mind. So it really caught me off-guard when several folks told me that they had bought it and were either reading it already or looking forward to it in their in-pile. Somewhat flabbergasted, I could only say, “Thank you. I hope you like it.” Maybe I’ll come up with something better in the future, but for now that’s all I’ve got.

So now we go back to the normal schedule. Exploring those new planets should come around next Monday.

So, what cool thing did you do over Memorial Day weekend?