Dan Thompson's Blog, page 11

March 4, 2013

The Last Book You’ll Ever Read

As I edit Ships of My Fathers, I’ve been thinking back to my father’s death. Specifically, I remember that towards the end, when it was clear that the second round of chemo was not going to work, he was reading a book on cosmology and faith. As a lifelong scientist and Christian, he was looking for some kind of reconciliation between two oft-conflicting viewpoints. I don’t know if he found what he was looking for, but I do remember thinking about mortality and limited time and that someday, I will be reading the last book I will ever read.

What kind of book is that going to be?

What kind of book is that going to be?

It might very well be something of a religious nature. I don’t expect that, since I don’t feel I have a lot of open questions in my theological view of the universe, but you never know what you’re going to do when you’re staring death in the eye.

But I like to think, instead, I’ll be reading fiction. Maybe I’ll reread some old favorite tale. Maybe I’ll be tearing my way through some new series that a friend recommended. I have always loved to escape into stories, and I think they will be a great comfort to me in my final days.

If I know the end is coming soon, I don’t think I’ll put the book down when I’m done and declare, “That was the last book.” More likely, I’ll pick up the sequel, because I want to know what happens next.

And isn’t that perhaps the best way to go? With the hunger for story and a thirst for that great mystery of what comes on the next page?

What do you think your last book will be?

March 1, 2013

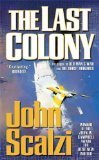

Review: The Last Colony, by John Scalzi

This is the third book in the Old Man’s War series, and it unites the storylines of the first two books. John Perry has been returned to human form, and Jane Sagan has been made human as well. They married and settled down on a world named Huckleberry, adopting Zoe, the orphaned daughter of a brilliant traitor.

This is the third book in the Old Man’s War series, and it unites the storylines of the first two books. John Perry has been returned to human form, and Jane Sagan has been made human as well. They married and settled down on a world named Huckleberry, adopting Zoe, the orphaned daughter of a brilliant traitor.

Everything was going fine, and then the Colonial Union asked them for a little favor.

So John, Jane, Zoe, and the rest of their household are off to form a new colony on Roanoke, except this is no ordinary colony. It’s a mix-mash of divergent cultures and almost seems designed to fail. And then they get the rug pulled out from under them when it turns out the Colonial Union has been… shall we say, less than truthful. From there it’s an engaging story of setting up a colony under less than ideal circumstances, hiding from aliens, and discovering the truth about what’s really going on.

This was probably my favorite of the series so far. It was all fresh material, and there were lots of problems to be solved, both practical and political. John, Jane, and Zoe all did humanity proud, even if it wasn’t always what the Colonial Union wanted. They also peeled the lid off of a static situation, and I’ll be interested to see where the story goes from here.

So, if you faltered during the Ghost Brigades, pick this one up and keep on marching.

February 27, 2013

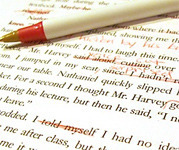

In the Copyedit Trenches

Sorry I’ve been quiet this week. I’m down in the copyedit trenches now for “Ships of My Fathers”. I’m supposed to hand it off to my professional copyeditor today, but it looks like that deadline is slipping to Thursday so that I can finish my own pass first.

So, in the meantime, I thought I’d share a few bits that managed to slip past my two beta testers and my three editing passes. In fairness, those passes were for editing story and language and were not being paranoid about diction and punctuation, but still, I’m amazed these got through:

Monty put his shoulder on Michael’s and gave it a good squeeze.

He fished out as wallet as he walked.

“How do you suggest we help Michael making this adjustment?”

She went on the measure the girth of his knees.

He did night try to hide his frown.

She added a puffy white roll to his place.

That’s all in the first third of the book, plus all the boring little punctuation stuff I had to fix. I still expect my copyeditor to find some errors. I just don’t want to embarrass myself in front of her.

February 22, 2013

Review: APE How to Publish a Book, by Guy Kawasaki and Shawn Welch

In this case, APE stands for Author, Publisher, Entrepreneur, which are the three roles you need to fill if you intend to self-publish in today’s publishing landscape. Since I’m self-publishing, I thought I’d give it a look and see if there was anything there for me. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much.

In this case, APE stands for Author, Publisher, Entrepreneur, which are the three roles you need to fill if you intend to self-publish in today’s publishing landscape. Since I’m self-publishing, I thought I’d give it a look and see if there was anything there for me. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much.

Certainly, the book is filled with lots of good information and primers. It would have been a great thing for me to read a year and a half ago. But now… most of the content of the book was stuff I’ve already figured out on my own. That doesn’t make me an expert, and I was hoping for more from these guys who supposedly are.

The Author section was mostly a collection of tools to use while writing (Word, Scrivener, etc.) as well as some arguments for pursuing self-publishing over the traditional path of submitting to a publisher. There was very little here on actual writing, but in fairness, that subject is too large and belongs in several other books on specific writing issues. Still, I felt pretty bored during the section and was eager to skip ahead.

The Publisher section was mostly about the nuts and bolts of taking your manuscript and getting it to the point where a reader could actually purchase it. This was pretty good, but I felt it gave too much credit to author service companies like those under the umbrella of Author Solutions without giving them the kind of critical analysis that the folks at Writer Beware do. Also, I would have liked to have seen more commentary on cover design as well as describing more mechanisms for creating e-book files. Nowhere did I see it mentioned that most e-book files are processed HTML and that the most reliable source format for the conversion is not Word or InDesign but HTML.

The Entrepreneur section was mostly about marketing. I didn’t see anything revolutionary here, just the same social media push that everyone else talks about. There was also a fair amount said about getting into the press via press reports, etc. I have mixed feelings about that. A lot of people tell you it’s a waste of time. Other people claim it gets them a lot of free publicity. Personally, I have a suspicion that it has less to do with your press release and who you send it to as it has to do with whether the recipient of that press release knows who you (or your traditional publisher) are.

So like I said, I would have found this useful before I started down the self-publishing path, but if you’ve already done it yourself, there won’t be much new stuff here.

February 20, 2013

Editing from First Draft to Final Draft

Folks often ask how many drafts are necessary, or how do you edit a novel, and so on. Like most things, I don’t believe there is One True Way, but I thought I’d share my own method. This is as much to point other people at later as it is to document my own process to help me remember when I get to this point on the next novel.

I already wrote about how I draft a novel, which is mostly an exercise in flying by the seat of my pants with only my destination and a few waypoints in mind. What I end up with from that is a mess. It’s not so much that the plot wanders all over – at least not so far – but that it’s filled with bad grammar, sloppy spelling, and a bucket-full of notes that look like this: [so, is the mom dead or not? need to fix this back in act 1] Character motivations are sloppy, major revelations are either broadcast too early or come out of nowhere, and the climax depends on something critical that I forgot to include in chapter three.

I already wrote about how I draft a novel, which is mostly an exercise in flying by the seat of my pants with only my destination and a few waypoints in mind. What I end up with from that is a mess. It’s not so much that the plot wanders all over – at least not so far – but that it’s filled with bad grammar, sloppy spelling, and a bucket-full of notes that look like this: [so, is the mom dead or not? need to fix this back in act 1] Character motivations are sloppy, major revelations are either broadcast too early or come out of nowhere, and the climax depends on something critical that I forgot to include in chapter three.

Clearly, it’s not ready for publication. It’s not ready for any kind of professional submission. It’s not even ready for me to show it to a friend. I call it my first draft, but even that is being a little too kind. Instead, I refer to it internally by a version number: version 0.9.

The absolutely first thing I do is nothing. I wait, typically at least two to three months, preferably while working on a different project, perhaps writing another draft of something else. It’s very important to get some distance from that first draft, because if I dive back in right away, I can’t really see it for what’s on the page. I still see it for what was in my head.

The absolutely first thing I do is nothing. I wait, typically at least two to three months, preferably while working on a different project, perhaps writing another draft of something else. It’s very important to get some distance from that first draft, because if I dive back in right away, I can’t really see it for what’s on the page. I still see it for what was in my head.

So, after waiting a while, the first real action I take is to make an edit pass all on my own. This edit pass starts with me printing out a copy. I take it to the local copy shop and get them to print it out on 8.5 x 11 sheets, single-spaced, but printed on only one side. I go with a spiral binding because that works out better for me physically. They put a clear front cover on it, and the first page has the working title, and the version history so far (since the initial vomit-draft may have been built up in stages of 0.10, 0.11, and so forth). I also make sure each page has the title, the version number, and the page number.

I then go through with a bright red pen. I’ve been using a Signo Uniball gel pen lately. Part of me still prefers the feel of the older Uniball Micro, but there’s a key difference that actually impacts the editing process. The Signo lets me open and close the pen simply by clicking on the end with my thumb, while the older Micro requires me to remove and replace the pen’s cap. I found that this simple change in the motion required both sped up my edits as well as got me to flag more items and make more notes.

I then go through with a bright red pen. I’ve been using a Signo Uniball gel pen lately. Part of me still prefers the feel of the older Uniball Micro, but there’s a key difference that actually impacts the editing process. The Signo lets me open and close the pen simply by clicking on the end with my thumb, while the older Micro requires me to remove and replace the pen’s cap. I found that this simple change in the motion required both sped up my edits as well as got me to flag more items and make more notes.

So, what am I flagging and noting? Well, what I’m not doing is trying to fine tune the language and catch all the typos. Certainly, if I see something, I’ll flag it, but that’s not the focus of this editing pass. Mostly, I’m looking for story and character problems. Did a cool character show up too late in the book? Is the protagonist’s major shift too predictable? Is that subplot boring? Does the climax really work as is? Remember that I’m doing this all on paper, so I’m not actually fixing anything. I’m just spotting problems. Some of the notes will fit in the margin, but longer notes go on the blank facing page – remember, I only printed on one-side of the pages. I’ll even go back and scribble notes like “This would be a good place to introduce the jailer. Insert a scene here.” Keeping it on paper forces me to look at the novel as a whole and doesn’t let me start making fixes before I’ve seen the entirety of the problems.

Then, once I’ve thoroughly bloodied the printout, I open up the document and start fixing things. Awkward sections get rewritten. New scenes are added. In my experience so far, the book grows about 5-10% during this stage. And while I’m not trying to make it perfect, I’ll at least make a pass through it with Word’s spelling and grammar checker. Most of the errors it flags are to be ignored (unusual names, unusual but not incorrect grammar, etc), but I try to fix any true errors it gives me.

Then, once I’ve thoroughly bloodied the printout, I open up the document and start fixing things. Awkward sections get rewritten. New scenes are added. In my experience so far, the book grows about 5-10% during this stage. And while I’m not trying to make it perfect, I’ll at least make a pass through it with Word’s spelling and grammar checker. Most of the errors it flags are to be ignored (unusual names, unusual but not incorrect grammar, etc), but I try to fix any true errors it gives me.

By this point, the story works and the characters are at least reasonable. I won’t say that this is the best I can make it, but it’s at least good enough to show it to someone. I call this version 1.0.

Then I go print out more copies of this one, just like the first one I printed. The history and version numbers are updated, but otherwise, it’s the exact same format. I pass these off to my beta readers.

I should say a thing or two about beta readers, but it would take up too much space. Suffice it to say, they know the genre, they know the difference between good stories and bad ones, and they’re not afraid to tell me something I won’t like. How you get those is probably another blog entry.

So anyway, I give the book to some beta readers. They get the physical copies of the book along with a brand new red pen. I make it clear to them that I want their reactions to the story, but they should feel free to mark up specific sections that need rework, identify typos, or simply jot down their immediate reactions in the margins. I give them a month.

After the month, I sit down and try to debrief them. I let them go through their copy page by page, and let their notes remind them of any thoughts they had. Meanwhile, I’m taking notes in a separate notebook. Afterwards, I’ll ask them for any other feedback, and when they are done I may ask them specific questions. Did the big reveal in chapter 12 surprise you, or had you figured it out already? I was trying to imply that Jake is Bill’s brother… did that get through? Did you believe in Sam’s redemption? At no time in all of this do I try to defend the work, tell them that they should have “gotten it”, or discredit their reactions. I just sit there and take notes.

Then I wait. Yes, again. It doesn’t have to be three months, but I like to wait at least a few weeks. Why? I have to let their feedback sink in. When I first get that feedback, it’s my instinct to defend my book. After all, it makes perfect sense in my head. The characters are quite believable. Justice is sweet, not contrived. So I sit on their feedback for a while, and think it over. After a month or so, I begin to see that there’s some truth to what they said.

Then I wait. Yes, again. It doesn’t have to be three months, but I like to wait at least a few weeks. Why? I have to let their feedback sink in. When I first get that feedback, it’s my instinct to defend my book. After all, it makes perfect sense in my head. The characters are quite believable. Justice is sweet, not contrived. So I sit on their feedback for a while, and think it over. After a month or so, I begin to see that there’s some truth to what they said.

So then I open up the document again, update the version number to 1.10, and start editing. I array all of the marked-up beta copies around me, and I go page by page, reworking problems that they identified. Some problems are too big for this style of editing, but as I go through, I’m reading my work as well, trying to see the bigger issues they found. Still, I keep plugging through to the end, fixing up the page-by-page stuff that I can.

And those big issues? There’s a reason for putting them off just a bit. You see, when I go through that page-by-page pass, I’m reading the novel again, and all the while I’m thinking about those big issues that the beta readers identified. For a lot of them, I’m kicking myself for not having seeing such a huge problem on my own. For others, I’m realizing that this was probably more about that particular beta reader than about my book. The rest are somewhere in between, but by the time I’ve read the book again while thinking about those bigger problems, I have an idea not only of whether they’re real but also of how to fix them.

So then I start hopping around doing heavier lifting. I add scenes. I rewrite dialog. I reorder events. This can be big and bloody, carving out organs and slamming new ones in their place. Depending on just how bloody this is, I may have to make a second read/edit pass to make sure I caught all the consistency issues. If I’m changing Bob’s gender, yeah, that’s going to take an extra pass, just looking for all the him/her stuff.

Then I think about how much I changed. Was it only a little? If so, then I’m pretty much done. But if the changes were big, then it’s back to the beta readers to get their feedback on the new version, 1.10. And that might result in even bigger changes, which have to go back to the beta readers as 1.20, and so on. Eventually though, I’ll either give up, or the changes will be small enough that I don’t feel the need to go back to the beta readers again. Thus, the answer to the question, “how many drafts does it take?” is “as many as it needs!”

And that is what I call my “final draft”, typically version 1.1 or 1.2. God help me if it ever gets to 4.5.

But what about word crafting and copyediting? After all, I kept saying above that I wasn’t worried about that stuff. Well, I push that off to a second kind of editing job that I call polishing, not editing. Polishing takes me from “final draft” to “final text”, and from there it’s yet another set of tasks of formatting, cover design, etc. that I call publishing. So, as I finish up polishing and publishing this next book, look for those to show up as entries of their own.

February 19, 2013

Finished with Ships of My Fathers Edits

Just a note to say that I finished up the edits to Ships of My Fathers last night. I’ll post something longwinded tomorrow about my editing process to put that in context. The short version is that the story is done, but I still have lots of polishing and copyediting left to do.

February 18, 2013

Secrets and Surprises

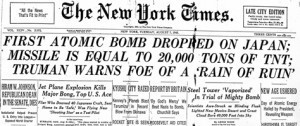

I once asked my grandfather what he had thought about the atomic bomb when the news of Hiroshima broke. I expected him to say he was surprised, and while he was, it wasn’t the surprise I had been expecting.

I once asked my grandfather what he had thought about the atomic bomb when the news of Hiroshima broke. I expected him to say he was surprised, and while he was, it wasn’t the surprise I had been expecting.

You see, he knew the atomic bomb was under development. In fact, most of the people in his office knew, too.

No, he was not working at Los Alamos, nor was he at Oak Ridge or any other Manhattan Project facility. He was an electrical engineer at Bell Labs in New Jersey. His main military effort during the war was for sonar.

So, given how secret the Manhattan Project was, how did he know about it?

It was the sudden silence in the various scientific publications. In the late 1930′s, there had been a steady stream of advances in the study of radioactive materials and how they transformed from one element to another. There were also theoretical hints around nuclear fission and what it could mean. He remembered expecting to read very soon that they had confirmed the splitting of the atom with details about energy output, particle emissions, and so forth.

Instead, there was nothing.

Mind you, my grandfather was not a nuclear scientist. In the day, that was more a sub-specialty of chemistry, but he wasn’t a chemist either. He worked on signal amplifiers and repeaters. In fact, he considered his greatest achievement to be a key development in the repeaters for the transatlantic telegraph lines.

But he read the scientific journals, just like all of his fellow engineers at Bell Labs, and when a lot of big names suddenly went silent, they began to wonder. Calls to various colleagues at universities came back with reports of certain professors and promising grad students going on extended sabbatical to parts unknown.

From an unrelated source, John Campbell of Astounding Stories also knew something was up, and he knew it was in New Mexico. According to the story, he knew this by how many subscriptions had suddenly moved there, and when he started noting the names on those subscriptions, he also put two and two together.

So what had my grandfather been surprised at? He said he was surprised by the reality of how powerful the atomic bomb was. Little Boy exploded as 16 kilotons. Fat Man was all the way up at 21 kilotons. While they had not talked in detail around the office — it was wartime, after all — the general feeling was that fission explosions might be one hundred times as powerful as chemical ones. Some argued for closer to a thousand times as powerful.

They knew high explosive bombs were getting up to one thousand and two thousand pounds, essentially a ton. They knew some of the limits of what the bombing aircraft could carry, and from that they estimated that the fission bombs might reach 500 to 1000 tons, i.e. one kiloton. “Of course,” he said,”we didn’t really know what a kiloton explosion would look like.”

But they got some idea in July of 1944 when the Port of Chicago (northeast of Oakland, CA) suffered a giant munitions explosion of about 1800 tons of TNT, i.e. 1.8 kilotons. A cousin of my grandfather’s had been one of the few surviving officers of the ship that exploded (the SS E. A. Bryan), and he had only survived by the luck of being on shore leave, visiting his girlfriend in nearby Oakland. Apparently he had felt the explosion through the ground, many miles away and could see the fireball rising over the horizon. But still, the much closer towns of Concord Pittsburg had not been particularly damaged.

But they got some idea in July of 1944 when the Port of Chicago (northeast of Oakland, CA) suffered a giant munitions explosion of about 1800 tons of TNT, i.e. 1.8 kilotons. A cousin of my grandfather’s had been one of the few surviving officers of the ship that exploded (the SS E. A. Bryan), and he had only survived by the luck of being on shore leave, visiting his girlfriend in nearby Oakland. Apparently he had felt the explosion through the ground, many miles away and could see the fireball rising over the horizon. But still, the much closer towns of Concord Pittsburg had not been particularly damaged.

Armed with what knowledge they had, my grandfather had expected fission bombs to be used as super “blockbusters”, and that bombers would blanket an industrial section of a city with five or six of them, possibly expanding to the larger city with another ten or twenty. He said one of his coworkers argued for fewer since the concentrated explosion would generate a more lethal shockwave than the larger pile of TNT had done in the Port Chicago explosion. Even then, it was assumed that a bombing raid would need at least four to ten to be equivalent to a larger TNT-based bombing.

It never occurred to him that it might be so powerful both in magnitude and in lethality that a single bomb could effectively destroy a mid-sized city. “It made me glad we were out of New York,” he said.

It never occurred to him that it might be so powerful both in magnitude and in lethality that a single bomb could effectively destroy a mid-sized city. “It made me glad we were out of New York,” he said.

The other surprise he confessed was that we had not used it on the Germans. It did not come out until later just how late in the war the bomb was ready, and he had spent much of the war wondering when he was going to see it being used in the European theater. Of course, none of them knew the logistics of gathering the fissionable material nor the design problems of making it work as an explosive, and it was that delay that caused a few of the detractors to suggest that no such effort was being made.

So, looking back on that, I wonder about our own future. If certain key researchers in quantum computing or nanotechnology suddenly went silent, would I know about it? If dark matter and dark energy theorists started disappearing into an Alaskan research institute would you realize it? I’m not one for conspiracy theories, but I have to wonder how many of us would notice if a relatively obscure research field suddenly went dark. Did they simply lose funding, or are we about to be surprised?

February 15, 2013

Review: Hounded, by Kevin Hearne

This one kept popping up in my Amazon “also bought” lists, so I figured I’d give it a shot. It’s an urban fantasy with ancient Irish gods, fairies, and druids fast forwarded to the twentieth century which has picked up its share of modern supernatural guys along the way.

This one kept popping up in my Amazon “also bought” lists, so I figured I’d give it a shot. It’s an urban fantasy with ancient Irish gods, fairies, and druids fast forwarded to the twentieth century which has picked up its share of modern supernatural guys along the way.

The protagonist is a druid named Atticus. Well, that’s what he’s calling himself these days, since not many folks in modern Arizona can handle his original name from sometime in the BC range. He runs an occult bookstore and tea shop, selling crystals and tarot cards to the wannabes and the occasional arcane text to the real practitioners. His lawyers (a vampire and a werewolf) keep him out of trouble – or at least try – but there’s not much they can do about his god problems.

And what would those be? Well, it seems he stole a sword in an epic battle a few thousand years ago, and its self-proclaimed “rightful owner” has been hunting for it ever since. Now those efforts have shifted into high gear, and Atticus is getting tired of hiding. Throw in a few witches and the occasional incarnation of Death (some sexy, some not so much), and it’s a regular menagerie of the supernatural.

By and large, I liked it, and I might continue reading the series. I suppose my only complaint is that the magic seemed too easy. That may just be the result of this druid’s thousands of years of practice, but for just starting into the series, he was a little too accomplished for my taste. It’s not that I require all my magical heroes to start off as neophytes, but it’s nice seeing them stumble and survive during those early years. It makes them seem more human rather that arrive as demigods on page 1.

February 13, 2013

Be Very Quiet, I’m Hunting Edits…

Sorry to be so quiet this week. I’m deep in edits for Ships of my Fathers…

February 8, 2013

Review: Burden of Proof, by John G. Hemry

This is the second book in Hemry’s legal-centric space opera, something of a JAG in space. I had a few complaints about the space portions of the first book, but those are pretty much gone in this one. The space stuff was pretty good, and again the legal side was fabulous.

This is the second book in Hemry’s legal-centric space opera, something of a JAG in space. I had a few complaints about the space portions of the first book, but those are pretty much gone in this one. The space stuff was pretty good, and again the legal side was fabulous.

In this book our hero Paul Sinclair has made it up to Lieutenant J.G. and has mounting responsibilities for various shipboard activities and still has that extra role of legal officer hanging around his neck. So when an onboard accident kills a crewman, he gets pulled into the investigation, not only as the legal officer but for his own actions.

But not only to the investigation results not add up, they point to him as having been at least partially to blame while some admiral’s slacker son is praised. Sometimes it’s best to just lie low, but Paul can’t do that. He begins his own investigation, and it leads to some very unpopular places.

So, on top of dealing with shipboard accidents, the angry father of a girlfriend, and the court martial of another officer, he’s got to figure out if circumstantial evidence is enough to meet… yeah, I’m going there… to meet the Burden of Proof.

All in all, this was a strong second showing for this series, so I’m definitely going to pick up the third at some point.