Jonathan Ball's Blog, page 63

February 8, 2013

Arman Kazemi reviews The Politics of Knives in the Vancouver Weekly

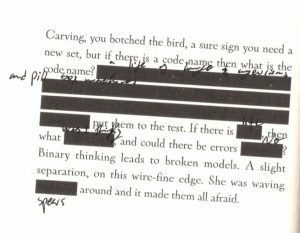

A clever review of The Politics of Knives in the Vancouver Weekly. I love that Kazemi engages with the book, writing his own lines over my “blanks” (black bars) in the title poem.

January 31, 2013

Interview with Ariel Gordon for Prairie Books NOW

Ariel Gordon kindly interviewed me for Prairie Books NOW and has posted a copy of the finished article on her site. As a “bonus,” I’ve posted the full interview below.

*

What would you like readers to know about The Politics of Knives?

That it’s not just a collection of nine long poems, but that they bleed across one another and have strange, sometimes hidden, sometimes clearer connection. That it’s not typical poetry: it’s more of an amalgamation of poetry, prose, fiction, and essay. That it’s secretly a book about film, just as Ex Machina was a book about books, and Clockfire was a book about theatre. The next poetry book I plan will be about visual art and tentatively titled The National Gallery. Then maybe I’m done with poetry, after that tetralogy of sorts. I feel almost done. We’ll see.

You say that The Politics of Knives is “secretly a book about film.” What do you mean by that, precisely?

At its core, The Politics of Knives is about how narrative requires and produces violence. Since film (by which I also mean video) is modern culture’s main method of recording and producing narratives, in various ways the book centres itself around film techniques and technologies. Sometimes obviously, as in the poem where K. (of Kafka’s The Castle) becomes a camera, or the poem about Hitchcock’s film Psycho, or the poem where a character records an elaborate suicide. Sometimes, though, in hidden ways, as in “That Most Terrible of Dogs,” which moves as if like a steadicam shot towards the very edge of the realm of Hades, or in “The Politics of Knives,” where black bars censor “sensitive” text as if in a government-censored document or a “cleaned-up” pornographic film.

What was your goal for this book? Do you think you met it?

My goal is always just to finish the book! So I definitely met that goal.

I spend a long time considering ideas and projects before I commit to them. I’ll spend years taking notes and thinking about a possible project while engaged in something else. When actually writing the book, by the time that happens, I’ve committed to a set of ideas and a core concept. My goal from that point on is just to develop the concept and trust the ideas. So by the time I actually start serious work on something, it has just become about the daily grind of getting the thing closer to being finished. When people usually ask a question like this, they mean artistic goals. But my artistic goals are achieved before I begin writing. My artistic goals are always to come up with a good idea for a book, one worth spending years to write, one I don’t see other people writing. Then I just try not to ruin the ideas, and finish the book.

My goals are all technical, then, by the time I actually begin writing in earnest. One of my goals while writing this book was to craft an invocation of the muse, but a modern and anti-Romantic one, to announce in some ways my “epic” subjects (violence, narrative, assassination, death, war). Once I settle on a goal like that, certain things fall into place. Invocations appear at an epic’s beginning, so I knew I’d have to put that poem first. It seemed that the manifesto in some ways was a type of modern, atheistic invocation, so I brought that idea to bear on the poem. I came up with the title “The Process Proposed” to suggest both that the poem triptych was an introduction of sorts, outlining the process I proposed to use throughout the book, but also to suggest that the process itself was a sentient force proposing a perverse marriage.

And so forth . . . when you talk about “goals” this is a difficult question to answer because my goal is just to execute the book. However, “executing the book,” for me, is a complicated process of varied, multi-level goals that involves a lot of decisions and technical experiments and, as in this case, can take years and require the help of outside readers and editors to help me gain or regain perspective, and so on.

I’ve heard you say in public that you’re bored with poetry. Or is it that you’re bored with your poetry? I can’t remember. Explain both/either statement, keeping in mind that you’ve published a book of poetry each of the last three years.

I probably said both. I’m bored with most poetry, maybe because I read so much, since I inherited that Winnipeg Free Press poetry review column from you. So much poetry is the same. You can just swap the poet’s names and swap the place names and swap a few other nouns. The song remains the same. They all have the same emotions. It’s funny to me that poets believe their emotions are unique and personal and then write a poem with the exact same emotional landscape as another poet, even some of the same imagery. My joke is that I don’t write poems about my feelings because as a straight, white male, aged 18-45, my experience is adequately represented in the culture.

I’m bored with my own poetry in the sense that early in my poetry career I became very good at writing those emotional poems (though I didn’t become excellent, as others are, since it wasn’t exciting for me). Now that I’ve abandoned that mode and tried to play with more experimental, cross-genre work, I find what most excites me is crossing genres to the point where I am almost entrenched in another genre. The prose-poem-plays of Clockfire would be the most obvious example, but in The Politics of Knives you can see a sequence like “He Paints the Room Red” as crossing over into fiction, and in fact that “poem” began life as a short story. A lot of the non-book poems I write are technical exercises, so even when they work out well, they seem somewhat mechanical to me, and I don’t write or publish that many as a result. The work in the books does not come from those exercises, they are more like practice for these books, the stuff that for me has real life and energy.

If you look at the books, The Politics of Knives is the one that seems the most like poetry, yet it works almost like an experimental novel, which may have been authored by the character inside of “He Paints the Room Red.” I could argue that Ex Machina is an experimental science fiction novel, and in fact it’s taught as such in a course in Calgary. Clockfire clearly shares more with Calvino’s Invisible Cities than it shares with other poetry. So I feel that my “poetry poetry” is some of my least successful work, whereas I’m proudest of these so-called “poetry” books, which I see as sort of an experimental, poeticized fiction. I’m happy to publish them as poetry because I think that’s the audience most likely to engage with them. In any case, I think of these books as “books” rather than poetry, which leads into your next question.

You’ve stated elsewhere that you’re uninterested in collections of poems. Why is that? Isn’t it enough that poems work at the unit of the poem? Why does the unit of the book take precedence for you?

I should clarify that I’m still interested in reading collections of poems, although it annoys me sometimes that they haven’t been presented in some more creative manner. They all seem to have the same structure, 3-4 sections of roughly equal length, etc. — it works for some books, like your Hump, but that’s an example of a book where I think it does have that sense of unity due to the subject of pregnancy, and there’s a clear pre-/during/post- structure that falls naturally into three parts. In most other cases it seems like the poet just opened up some “poetry book template” that came pre-loaded with the word processor and filled in the blank areas with so-called “epiphanies.”

I think that with the advance of new technologies, we need to ask a question we should have asked a hundred or more years ago, which is, What constitutes a book? For me, the book is a unit of composition and a conceptual object. It’s not a physical container for text (e.g., the codex) and so it’s not just a place to put poems. A poem working at the unit of the poem is important, of course, but books aren’t poems.

The assumption that once you have 80 pages of excellent poetry you should slap on a title and call it a book seems insane to me. That’s just 80 pages of excellent poetry. Great for the poet, but once s/he has that there are literally 80 different things that those pages demand. Do they demand to be in a book? Possibly. Maybe there is a book lurking there somewhere. But most of the time instead of a “book” we get a bunch of pages of poetry, however good. I might still love reading it, but there’s a difference to me. The book is a unit of composition and once the pages sit between covers, along a spine, or even as a single file in my eReader, the context of presentation alters the meaning of each work. It opens up vistas of possible play that don’t get developed, because the poet isn’t truly engaged with and attentive to the medium s/he has (by default, and therefore accidentally) chosen.

The unit of the book takes precedence for me because I prefer books to single poems. There’s no necessary reason why it should take precedence otherwise: it’s a preference. Besides, all those poems have so many ways to get out into the world, why pick the most culturally invisible mode (the book) as your default choice? Of course, it’s my own bad luck that I’ve selected this mode as my unit of composition, but others don’t need to suffer this fate.

Has writing screenplays and poems helped you write fiction, as I understand was your original plan?

Yes and no. It certainly took more time. It may have been smarter to just write fiction, as practice for fiction, which seemed idiotic to me at the time even though it seems commonsensical now, and to most people. However, I feel this odd tactic worked. Instead of just becoming better at producing the kind of fiction I see around me, I began to look at fiction from the perspective of both a poet and a screenwriter, and I think I’m producing more visceral, innovative, and interesting work than I would have otherwise — but I’ll never know. At minimum, I’ve published three books of poetry and sold a short film to The Comedy Network, so if I fail as a fictioneer I’ll still have those accomplishments to build upon.

How do you approach performance? Has your approach changed as you’ve toured your books?

I hate performing, so I just try to be as brief and engaging as possible and as the audience seems to desire. I don’t like to take myself too seriously, even when writing about serious subjects. The reader can read the book herself or himself. The only reason for anyone to go to the event is to engage with the author. So I try to engage, and be a personality, not a blur with a monotone. That said, my best reading was the Toronto Clockfire launch, which I couldn’t attend. Instead I sent an actor to play me all night (Aleksander Rzeszowski). He gave a reading and signed books and stayed in character as “Jonathan Ball” for the entire evening and by all accounts it was the best reading I ever gave.

How does teaching literature help/hinder your writing?

It helps to see how students read, what they respond to — I’ve found that, on the whole, they respond well to unusual texts. They are fine with complex concepts, strange writing methods — as long as they find something visceral and engaging in the work. I continually use strange, demanding texts alongside more canonical, conservative ones, but they rarely fail to engage if the text attempts to engage them. They rate the texts higher than they rate me! Which is certainly not common wisdom in publishing, where something strange gets viewed as a tough sell. It’s an easier sell to students, who find the uncommon exciting.

Then again, they are a self-selecting group, in the sense that they signed up to take an Intro English course. Major publishers have primarily targeted non-readers for decades, people who only buy books by celebrities at Christmas, or only buy the nonsense that everybody’s talking about for no good reason, so it wouldn’t make sense to a major publisher to actually wonder what readers read, but I do. However, it takes time to teach, and because I teach on contracts it takes a lot of time for very little money, so it’s a hindrance in that respect. On a basic level, studying literature helps you understand literature, so I feel that as my analytical skill increases, I become better at analyzing my own work and thus more efficient in writing and editing, so I hope that helps “make up” for the time I spend marking when I could be writing.

Tell me your theories about time management.

My goal is to be as creative as possible in the work, and to achieve that I need to mechanize my life as much as possible outside of the work. I’m always in the process of developing and refining routines, and trying to follow them (the hardest part), with the goal of getting menial tasks done as quickly and thoughtlessly as possible and freeing my mind and time up for being creative with the work.

I literally have index cards lying around with numbered routines written out on them, to complete regular tasks without getting distracted or obsessive, which are both far too easy for me to do and which waste tons of my time. The point of this is to keep myself focused as much as I can. If I don’t, not only do I waste time unproductively, but I even waste it productively (which is still a sort of waste). In the past, I’ve had the problem of jumping from project to project. That’s created a situation where I have so much half-finished or first-drafted stuff that I am now mostly just rewriting and finishing things, and doing very little “new” writing (although I did a lot for The Politics of Knives recently).

I see books as the main things I do, so I try to force myself to focus on them before I move on to the obligations. I try to force 500 words on a book project out of myself every day, if not more. 250 minimum, although I fall off the wagon from time to time. I suspect this simple thing is the reason I’m relatively productive compared to other writers. A lot of writers waste time waiting for inspiration or trying to boil their tea or find the perfect writing song or hat or some other bullshit.

People sometimes tell me that it’s not possible to have rigorous habits and schedules and be creative and original. As if should you drink the same tea every day you can’t come up with a truly impressive line of poetry. In fact, slavish adherence to habits frees you to focus your creativity elsewhere. I don’t waste creative thinking on making the perfect iTunes playlist, one that the character in my story might listen to, or one that suits the mood of the piece. I just listen to the same 500 metal songs on random for a decade. When I suck it’s when I am too lazy or stupid or stressed and I ignore the routines and habits I’ve set up. That’s when I produce lousy work or nothing at all or start procrastinating or freak out about everything left undone and the pile of papers messing up the shelf over there. These routines and habits aren’t random, they’re designed to reduce the energy that goes elsewhere and focus me on the work, against my slothful instincts or anxieties.

A lot of my writer friends say that walking can be writing, or reading can be writing, or some other thing, as long as you’re working on the book in your mind, or doing an interview like this to promote the book, you’re still writing. That’s absolute horseshit. Look up writing in the dictionary. Taking long, thoughtful walks or pondering a character’s motivations over tea isn’t writing. Maybe such things are important, but they are of secondary or tertiary importance. They are to be done in spare time. Only putting words on a page and revising those words is writing.

Where will you be as a writer in ten years? (I’m sure you have a plan…)

I’m trying to be better at having plans. I have a list of things I want to do, and in ten years I just want to have checked off as many things as possible. Here’s the rundown of what I’m doing “next” (it always changes, depending on circumstance — my novel keeps getting pushed back because another book is accepted, or grant awarded, or whatever). Let’s say (generously!!!) that 10 years = 10 projects.

• Revamping my website (www.jonathanball.com) to fill it with resources for writers and students

• An academic monograph on a Canadian filmmaker/film called John Paizs’ Crime Wave

• A short story collection called The Lightning of Possible Storms

• A debut novel called The Crow Murders, a literary horror

• A book of literary criticism called In the World of the Dead

• An academic study called The Book to Come

• A graphic novel called The Eye Collector, an adaptation of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “Der Sandmann”

• A poetry book called The National Gallery

• A comic book series called Dirk Dirkson vs. The Demons from Mars, a horror comedy

• Syndicating my “Haiku Horoscopes” column

If I could do all that I’d be impressed with myself. Cross your fingers!

January 12, 2013

This Hisses

My favourite band, THIS HISSES, is releasing a new album. Give the single your time (the ending is especially haunting). If you don’t know THIS HISSES, they sound something like Sleater-Kinney being murdered by The Birthday Party.

January 6, 2013

Interview in Prairie Books Now

The wonderful Ariel Gordon interviewed me for Prairie Books Now: you can read the article here.

December 31, 2012

My 2012 Reading List

Ryan Fitzpatrick and I started what we call “the 95 books challenge” a few years ago, with a goal to reading at least 95 books per year (with the larger goal to become more well-read than George W. Bush).

I beat Ryan every year until this one, when he blew me out of the water. I re/wrote two books this year, on top of more-than-full-time work, but still, a loss is a loss. Anyway, I still met the 95 goal by reading 112 books.

My reading breaks down in a few ways. I read or reread critical theory and nonfiction, self-help or writing-related books (usually because I am trying to learn something to answer questions from students: I rarely recommend these books to others, and they are mostly garbage), fiction and graphic novels and much poetry for my poetry review column in the Winnipeg Free Press. I also do a lot of reading that I don’t count, since I start and then stop a book or only read a few chapters.

If I had to recommend a handful of books here, this is how it would break down:

Theory/Non-Fiction: The Impossible David Lynch by Todd McGowan is simply the best book on David Lynch.

Self-Help/Writing: These books are mostly crap, as I say, but I was surprised by how intelligent and useful Story by Robert McKee (I book I had avoided in the past due to its reputation as a screenwriting “rulebook”) turned out to be.

Fiction: Automatic World by Struan Sinclair (obviously The Castle by Kafka is a better book, but who needs me to recommend it?)

Graphic Novels: I re-read and still love the amazing Imagination Manifesto series by GMB Chomichuk et al.

Poetry: See my 2012 best-of column.

1. What Your Body Says (Sharon Sayler)

2. The Best Canadian Poetry in English 2011 (eds Priscila Uppal and Molly Peacock)

3. Carapace (Laura Lush)

4. Discovery Passages (Garry Thomas Morse)

5. Writing the Breakout Novel (Donald Maass)

6. Lyrics and Poems 1997-2012 (John K. Samson)

7. Point Omega (Don DeLillo)

8. Imagination Manifesto 1 (GMB Chomichuk et al)

9. Imagination Manifesto 2 (GMB Chomichuk et al)

10. Imagination Manifesto 3 (GMB Chomichuk et al)

11. Drift (Kevin Connolly)

12. Hordes of Writing (Chus Pato)

13. A (short) history of l. (rob mclennan)

14. Starve Better: Surviving the Endless Horror of the Writing Life (Nick Mamatas)

15. Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain (David Eagleman)

16. Zombie Fight Night: Battles of the Dead (A. P. Fuchs)

17. The Unmemntioable (Erin Moure)

18. Story (Robert McKee)

19. Nox (Anne Carson)

20. Happyland (Kevin Connolly)

21. Killdeer (Phil Hall)

22. Testament (Dennis Lee)

23. Games of Chance (Gerald Beirne)

24. New Theatre (Susan Steudel)

25. Shoot It!: Hollywood Inc. and the Rising of Independent Film (David Spaner)

26. Plans Deranged by Time (George Fetherling, ed. A. F. Moritz)

27. Franzlations: The Imaginary Kafka Parables (Gary Barwin, Craig Conley, Hugh Thomas)

28. A Season in Hell and The Drunken Boat (Arthur Rimbaud)

29. A Complete Encyclopedia of Different Types of People (Gabe Foreman)

30. The Humbugs Diet (Robert Majzels)

31. A Woman Clothed in Words (Anne Szumigalski)

32. Divide and Rule (Walid Bitar)

33. quase flanders, quase extremadura (Andres Ajens, trans Erin Moure)

34. The 4-Hour Workweek (Timothy Ferriss)

35. The Castle (Franz Kafka)

36. K. (Roberto Calasso)

37. Paradoxides (Don McKay)

38. Roughing it in the Market: A Survival Toolkit for the Savvy Writer (Angie Gallop)

39. Confessions of a Young Novelist (Umberto Eco)

40. Assiniboia (Tim Lilburn)

41. The Least Important Man (Alex Boyd)

42. Payback (Margaret Atwood)

43. After Kafka: The Influence of Kafka’s Fiction (Shimon Sandbank)

44. House of Holes (Nicholas Baker)

45. The Anthology of Really Important Modern Poetry (Kathryn & Ross Petras)

46. You Exist. Details Follow. (Stuart Ross)

47. Workbook: memos & dispatches on writing (Steven Heighton)

48. Boy (Victor Enns)

49. A Dark Boat (Patrick Friesen)

50. Postmodernist Fiction (Brian McHale)

51. Doom (Natalie Zina Walschots)

52. Personals (Ian Williams)

53. In Praise of Copying (Marcus Boon)

54. How to Write Groundhog Day (Danny Rubin)

55. We, Beasts (Oana Avasilichioaei)

56. Antigonick (Sophokles trans. Anne Carson)

57. The Procrastination Equation (Piers Steel)

58. One False Move (Tim Conley)

59. Joe Hill’s The Cape (Jason Ciaramella, Zach Howard, and Nelson Daniel)

60. Derrida, An Egyptian (Peter Sloterdijk)

61. The Hard Return (Marcus McCann)

62. Gasping for Airtime (Jay Mohr)

63. Chaser (Erin Knight)

64. Ronald Reagan, My Father (Brian Joseph Davis)

65. This Way (Lise Downe)

66. Writing Picture Books (Ann Whitford Paul)

67. Grid (Brenda Schmidt)

68. Locke & Key: Clockworks (Joe Hill & Gabriel Rodriguez)

69. The Poetry Home Repair Manual (Ted Kooser)

70. Form of Forms (Mark Goldstein)

71. Vlad (Carlos Fuentes)

72. Low Moon (Jason)

73. Fortified Castles (Ryan Fitzpatrick) – unpublished

74. Repeater (Andrew McEwan)

75. How to Write a Sentence (Stanley Fish)

76. Floating Life (Moez Surani)

77. The Art of Dramatic Writing (Lajos Egri)

78. Monstrance (Sarah Klassen)

79. Help! for Writers (Roy Peter Clark)

80. How I Sold 1 Million eBooks in 5 Months (John Locke)

81. Thirty Poems (Robert Walser)

82. Writing the TV Drama Series (Pamela Douglas)

83. A Theory of Parody (Linda Hutcheon)

84. Firewalk (Katherine Bitney)

85. Automatic World (Struan Sinclair)

86. 50 American Plays (Matthew Dickman and Michael Dickman)

87. Simulations (Jean Baudrillard)

88. Sonar (Kristian Enright)

89. Amphetamine Heart (Liz Worth)

90. The Willpower Instinct (Kelly McGonigal)

91. Bent at the Spine (Nicole Markotic)

92. Gethsemene Hall (David Annandale)

93. Journey with No Maps: A Life of P.K. Page (Sandra Djwa)

94. The Book of Marvels (Lorna Crozier)

95. Seen of the Crime (derek beaulieu)

96. Lazy Bastardism (Carmine Starnino)

97. Nice Weather (Frederick Seidel)

98. Letters to a Young Contrarian (Christopher Hitchens)

99. Undark (Sandy Pool)

100. Trobairitz (Catherine Owen)

101. The Archive Carpet (Michael Hetherington)

102. Guy Maddin: Interviews (ed. D. K. Holm)

103. The Fifty Year Sword (Mark Z. Danielewski)

104. Demon Theory (Stephen Graham Jones)

105. Ring (Koji Suzuki)

106. Natural Capital (Jason Heroux)

107. The Impossible David Lynch (Todd McGowan)

108. I Am Legend (Richard Matheson)

109. Create Your Writer Platform (Chuck Sambuchino)

110. The Plague of Fantasies (Slavoj Zizek)

111. The Art of the Ridiculous Sublime: On David Lynch’s Lost Highway (Slavoj Zizek)

112. Calculating God (Robert J. Sawyer)

December 29, 2012

My Top 12 Poetry List

My monthly poetry review column is already a “best-of” list (the best poetry books I read that month), so in December the Winnipeg Free Press asked me to pick a number of those previously reviewed books as a best-of the year column. My “Top 12 for 2012″ article (with mini-reviews) is available at the Winnipeg Free Press site, and the list itself is repeated below. The standard caveats that I don’t read everything, etc., apply.

* 50 AMERICAN PLAYS by Matthew and Michael Dickman

* ANTIGONICK by Anne Carson

* UNDARK: AN ORATORIO by Sandy Pool

* REPEATER by Andrew McEwan

* NEW THEATRE by Sue Steudel

* WE, BEASTS by Oana Avasilichioaei

* THE UNMEMNTIOABLE by Erin Moure

* DOOM: LOVE POEMS FOR SUPERVILLAINS by Natalie Zina Walschots

* SONAR by Kristian Enright

* YOU EXIST. DETAILS FOLLOW. by Stuart Ross

* PERSONALS by Ian Williams

* TESTAMENT by Dennis Lee

December 27, 2012

8-Ball Interview with Spencer Gordon

1. What do you want to talk about—which question do you wish interviewers would ask, and what is your answer?

I’m usually asked about my influences (regarding Cosmo), and it’s kind of boring and embarrassing to just rattle off some names. I’d like an interviewer to be more specific—to isolate a particular story or section, a particular passage, and ask about what (or who) motivated its construction. To show that an interviewer has not only read my book, but done some research before firing me some generic questions. I was really knocked out by Rob Benvie’s discussion of David Foster Wallace’s essay “E Unibus Pluram: Television and US Fiction” (1993) in his review of Cosmo for HTMLGIANT, not only because it [the essay] was an incredibly important piece of thinking and writing for me, but because the reviewer was perceptive and well-read enough to identify it. I would love an interviewer to bring up specific names and/or literary works—especially my American influences, since they’re more numerous and more significant for the creation of Cosmo than their Canadian counterparts—and ask me how these went into the formation of the book (as all books are influenced by a multitude of sources, literary and otherwise). I’d be excited by questions about theory, too: not the general, “what theories influence you?” kind of question, but (again) the type that narrow the field. Cosmo benefitted from a study of a whole whack of thinkers—Allan Bloom, Christopher Lasch, Charles Taylor, Pierre Bourdieau, and dozens more—and it would be excellent and exciting to have an interview wander and expand from the source text in creative and surprising ways.

2. What advice do you wish you’d received, but didn’t, when you first started to take your writing seriously?

“Poets are mean and they will try to kill you.” Or, “Don’t suck up to other poets. Well, OK, you will do so, of course, like all poets do, but when you do, feel it in your bones. Take this self-knowledge and turn it into a weapon you wield without mercy.” Both of these are from ‘asshole’ and ‘parasitic’ poet Kent Johnson.

3. What is wrong with the publishing industry, and what are they getting right?

I don’t really know enough about the publishing industry to comment. I’d imagine the main problems involve mismanaging or misinterpreting audience and demand.

4. How will technology change writing?

The typewriter replaces the pen; the computer replaces the typewriter. New technologies will no doubt make writing exciting and necessary for a different generation of practitioners. I am old enough to have begun writing with pen and paper, to move to an electric typewriter, and then to a word processor (all within the span of six years or so—I’m still fresh). It’s exciting to imagine another way to compose blocks of prose, how things might evolve, as I get older and balder and fatter.

One notion that I like to challenge is the idea that one cannot get proper writing done when surrounded by technological distractions. Franzen talks about this. He says you’ve got to disable your Internet connection. I completely understand what he means, but I think it’s a last gasp type of scenario, a holdover from another era. I’d like to imagine texts that cannot be produced without an Internet connection, what those might look like. I think that’s a more exciting notion than the conventional, albeit stable, ideas of solemn, undisturbed focus. I tried to do this (at least partially) with the story “Frankie+Hilary+Romeo+Abigail+Helen: An Intermission” in Cosmo.

To change topics slightly, if I may—reading is increasingly transgressive, and at least in part due to changes in technology. I see this as an educator and as a person still in his twenties. I don’t know if this is statistically, verifiably true, but whatever; I have the feeling that young people are reading less and less. The comportment with which one must attend a difficult text is nearly extinct among students (or at least my students). Basic proficiency—in comprehension, composition, analysis—is evaporating. And while young people may be reading constantly, frantically, it’s not the type of reading that engenders genuine literacy. What I mean by reading is a turning inward; a silencing; a carving of space from the gymnastic stridency of urban, smart-phone living. It’s what any lucky child remembers as his or her best, and often earliest, experiences with books. To read with comportment and attention and discipline is to push aside, to make room, and to say no: retreating and refusing the charms of capital and power. Nothing about our power structures, our conservative majority (which exists in politics and education as well as in literary institutions) encourages this movement. But who knows. The pendulum may careen back, too.

5. What is your process for a typical piece of writing, from idea to publication? (Give a specific example.)

Stories start somewhere weird—usually a brief scene, a stirring, an emotion—and then sit somewhere in my brain for a very long time, completely unattended. Once one of these flashes becomes pervasive, recurring, and I realize I’m becoming slightly obsessed, I know that fiction must be the result, at least one day. I don’t try to rush this process. I let the story or novella ferment and stew. There’s a moment of commitment, after which I begin researching locations, set pieces, actors, models, and so forth. This is terribly exciting. Then I start plunking down words. This is awfully terrifying because the first words are always so bad. It’s difficult. I hurt. I roll around. I drink a lot. Finally, some order begins to arise from the confusion. Suddenly it’s done. Then the putting away and the editing begins, which can take years.

My stories were notoriously (well, in my own mind) unpublishable by the larger magazines. Probably because they were too odd and broken, but part of me always sighed in despair seeing the lame-ass pieces that beat mine for space. I sent out early drafts of all ten stories in Cosmo to major literary journals multiple times; every one of them was rejected, often without a note. So my only real experience with publication was having Coach House say yes to the manuscript. As you can imagine, it made me feel like I was just asked to prom by the prettiest creature in school (well, maybe not the prettiest, but at least the coolest, the one with the best taste, the one way beyond the other kids …).

Poetry is different. I’ve published lots of poems. I don’t care as much. Maybe that means my fiction isn’t as good. Or it means that my poetry is actually serving the needs of The Literary Conservative Majority and my fiction isn’t. I’m not sure. All I know is that both acts of writing make me happy and I’m not really upset by being ignored (i.e., rejected) anymore because I know my fiction is too badass for them haters (and Con. Maj. Reps) to process.

6. What are your daily habits as a writer, and as a reader?

My daily habits as a writer are nonexistent. I write intermittently and when I feel most positive about my life and skillz (and when time and work allow; I am not wealthy [obviously] and I am a social animal [i.e., I lack the sociopathic and narcissistic tendencies required to eliminate responsibilities to other people and to effectively ‘shut the door,’ as many other writers do, and yes, I’m jelly]). I’m not sure how I’m doing this now. When did life become so full and busy?

In more positive terms, I write when it feels right. Like Palahniuk’s shitting analogy—don’t jump on the john unless you have to. Never force one. Something might tear, or worse.

As a reader, I sniff around books of fiction suspiciously. I hate finding ‘scaffolding’ in literary fiction. I hate seeing devices, transitions, techniques to bridge, attempts to incorporate backstory, etc., even while doing so I feel all smart and perceptive. I want to get lost and be thrilled by the surety of a voice or the empty-glass clarity of a writer’s mechanics. Once I’m not picking at structure, I read voraciously and gleefully. As for poetry, everything depends on withholding judgment. I work to become slow and methodical and empty of expectation.

But god, I don’t read enough. I’m constantly amazed by how happy I am to have a great collection or novel near me as I move through the sludge of life—amazed that it’s happening this way and amazed that I don’t indulge and escape more often. Remember those days when you first found that the life in books seemed to mend the wounds of ‘real’ life? That literature was the most exciting and important thing about life? I used to stay up late talking on the phone to a friend about books. I was fourteen. We don’t really talk about books anymore, but nothing quite as grand and mesmerizing has taken their place …

7. What is your ambition as a writer—what do you want to accomplish, personally and professionally?

To borrow a quotation from 2Pac’s “Unconditional Love”:

Driven by my ambitions, desire higher positions,

so I proceed to make Gs eternally in my mission

is to be more than just a rap musician—

the elevation of today’s generation

if I could make ’em listen …

My ambitions are, for now, to outdo myself with each project, to avoid lateral movement and pursue forward momentum. I am starting to realize that whatever I do must be a personal victory; I cannot expect congratulations or praise or cultural credit in any form. This may sound naïve or obvious, but it’s a sharp pill to swallow.

I see a small river shooting from the main channel. It may not be a river at all; it might be more like a dirty creek. But I’ve started down this little stream, pushing my paddle in the murky water, following its twists and turns as the sounds of the primary course begin to fade. Where am I going? Is anyone watching? Who will know I’m gone? Who will be waiting at the end? Is there an end?

Sometimes I fear that this river is only one that roils inward; that there is no physical destination; that we are all curling up like drying, dying leaves, into ourselves, before we disappear. Let’s be fearless and happy like autumn.

8. Why don’t you quit?

Seriously? You’ve gotta believe that there’s more to say. And only you can say it in the precise way that it demands to be said.

In other words, have faith in the way you spit. Know that others can’t shine like that.

In other words: can’t stop, won’t stop.

Spencer Gordon holds an MA from the University of Toronto. He is co-editor of the online literary journal The Puritan and the Toronto-based micro-press Ferno House. His own stories, articles and poems have been published in numerous periodicals and anthologies. He blogs at dangerousliterature.blogspot.com and teaches writing at Humber College.

December 23, 2012

December 19, 2012

Žižek explains my obsessive creation of new “master” files when writing

This actually caused a production problem when publishing The Politics of Knives, since I create multiple “master” files for my writing (at any moment, I have up to 10 “master” files for the same work hiding in different computer folders) . . . Žižek isn’t using “master” in this sense, but it works regardless. It also explains the need for an outside editor/publisher (another reason for would-be writers to continue dealing with traditional presses):

As any [writer] knows, the problem with writing on the computer is that it potentially suspends the difference between ‘mere drafts’ and the ‘final version’: there is no longer a ‘final version’ or a ‘definitive text’, since at every stage the text can be further worked on ad infinitum — every version has the status of something ‘virtual’ (conditional, provisional). . . . This uncertainty, of course, opens up the space of the demand for a new Master whose arbitrary gesture would declare some version the ‘final’ one, thereby bringing about the ‘collapse’ of the virtual infinity into definitive reality. (Slavoj Žižek, The Plague of Fantasies, 151)

December 6, 2012

Hamlet: The Choose-Your-Own-Adventure Book

Ryan North’s upcoming project is as exciting to me as his innovative use of the Kickstarter crowd-funding platform. I don’t have a lot of spare time these days, so instead of my sharing my thoughts about it, take a look at its brilliance for yourself.

What really excites me about this are two things: (1) that I could teach Hamlet alongside To Be Or Not To Be: That Is The Adventure in a speculative future where students see how Shakespeare and experimental literature come together at last in an orgasm of hilarity, and (2) that North’s innovative use of the crowd-funding tier structure serves as an interesting model for (perhaps less-guaranteed to crowd-please) experimental, hybrid-media literary projects… like the ones I always seem to be working on…

Anyway, I want to see this project fully-funded so that I can see what is up his sleeve at the final tier. He’s already promised a stage performance where the entire Internet votes on what happens next – where else could he go?