Kimberly K. Arcand's Blog, page 2

October 3, 2017

Book Trailer Released

We are about a month away from our latest book, "Magnitude: The Scale of the Universe" being released (November 7, 2017)! To celebrate, today we are dropping our homemade book trailer. Yes, that's right, we made it ourselves with very little video production expertise on hand. (And yes, you can definitely tell it's made by novices, but we think that's part of the overly-dramatic, slightly tacky, film-school-newbie fun.) We hope you enjoy a glimpse of our upcoming book!

Published on October 03, 2017 13:35

September 23, 2017

The Magnitude of Earthquakes

This week’s horrific and heartbreaking earthquake in Mexico is a reminder of the destructive power earthquakes can deliver. It also comes on the heels of another earthquake in a different part of Mexico just two weeks before. Relief map of Mexico. Credit: Carport, CC By 3.0One of the first facts to be reported about an earthquake is its magnitude. Many of us might be familiar with the term “Richter scale,” which was developed in the 1930s by two scientists at Caltech. The Richter scale was replaced in the 1970s by what is known as the “moment magnitude scale” that more accurately measures the impact of earthquakes.For non-geologists (such as ourselves) the difference between the Richter and moment magnitude scale could seem unnecessary to distinguish since they often report the same basic results. The most important thing we know about any measurement of the magnitude of an earthquake is that the bigger the number, the worse the earthquake.One useful point about the moment magnitude scale is that it is logarithmic, where each whole number represents a factor of 32. Therefore, the difference in two whole numbers of the magnitude means that an earthquake is 1,000 times stronger. For example, a 7.0 magnitude earthquake releases 1,000 times more energy than a 5.0 one. (An excellent article in the Los Angeles Times on the history and current use of magnitude in earthquakes can be found here)

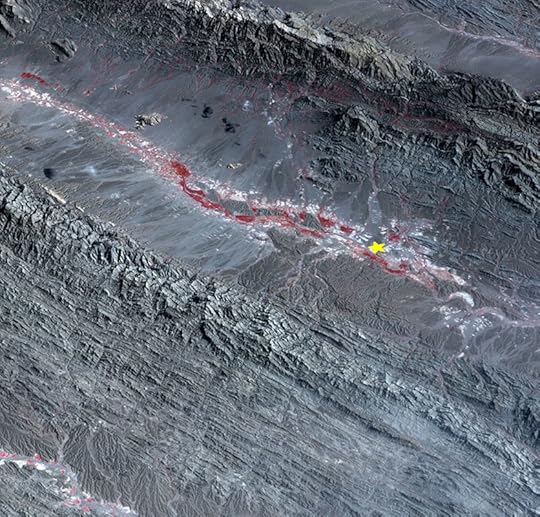

Relief map of Mexico. Credit: Carport, CC By 3.0One of the first facts to be reported about an earthquake is its magnitude. Many of us might be familiar with the term “Richter scale,” which was developed in the 1930s by two scientists at Caltech. The Richter scale was replaced in the 1970s by what is known as the “moment magnitude scale” that more accurately measures the impact of earthquakes.For non-geologists (such as ourselves) the difference between the Richter and moment magnitude scale could seem unnecessary to distinguish since they often report the same basic results. The most important thing we know about any measurement of the magnitude of an earthquake is that the bigger the number, the worse the earthquake.One useful point about the moment magnitude scale is that it is logarithmic, where each whole number represents a factor of 32. Therefore, the difference in two whole numbers of the magnitude means that an earthquake is 1,000 times stronger. For example, a 7.0 magnitude earthquake releases 1,000 times more energy than a 5.0 one. (An excellent article in the Los Angeles Times on the history and current use of magnitude in earthquakes can be found here) Space-based satellites can monitor Earth's changing surface, and map earthquakes, such as the one above in Pakistan from 2012. Credit: NASA/GSFC/METI/ERSDAC/JAROS, and U.S./Japan ASTER Science TeamThe word “magnitude” means many things, including “great extent” and “importance” and a “basis for comparison” as well as the language used to describe the extent to which an earthquake can cause harm.We chose the term “magnitude” for the title of our latest book for all of those definitions and uses. We are avid believers that science intersects with our daily lives in a host of ways that many of us might overlook. One of our goals in writing popular books is to help show that there is no “church and state” separation, if you will, between those who are affected by science and those who aren’t (be it a natural disaster, a new farming technique, or a different kind of medicine).We cannot control when the ground beneath us shakes. But we can do our best to stay informed on the latest scientific concepts, topics and terms. It is one small way that we can improve responses to whatever natural or human-made challenges we might face. To use a clichéd phrase, it is how we can best begin to understand the magnitude of a situation. A version of this blog was also published on HuffPost

Space-based satellites can monitor Earth's changing surface, and map earthquakes, such as the one above in Pakistan from 2012. Credit: NASA/GSFC/METI/ERSDAC/JAROS, and U.S./Japan ASTER Science TeamThe word “magnitude” means many things, including “great extent” and “importance” and a “basis for comparison” as well as the language used to describe the extent to which an earthquake can cause harm.We chose the term “magnitude” for the title of our latest book for all of those definitions and uses. We are avid believers that science intersects with our daily lives in a host of ways that many of us might overlook. One of our goals in writing popular books is to help show that there is no “church and state” separation, if you will, between those who are affected by science and those who aren’t (be it a natural disaster, a new farming technique, or a different kind of medicine).We cannot control when the ground beneath us shakes. But we can do our best to stay informed on the latest scientific concepts, topics and terms. It is one small way that we can improve responses to whatever natural or human-made challenges we might face. To use a clichéd phrase, it is how we can best begin to understand the magnitude of a situation. A version of this blog was also published on HuffPost

Relief map of Mexico. Credit: Carport, CC By 3.0One of the first facts to be reported about an earthquake is its magnitude. Many of us might be familiar with the term “Richter scale,” which was developed in the 1930s by two scientists at Caltech. The Richter scale was replaced in the 1970s by what is known as the “moment magnitude scale” that more accurately measures the impact of earthquakes.For non-geologists (such as ourselves) the difference between the Richter and moment magnitude scale could seem unnecessary to distinguish since they often report the same basic results. The most important thing we know about any measurement of the magnitude of an earthquake is that the bigger the number, the worse the earthquake.One useful point about the moment magnitude scale is that it is logarithmic, where each whole number represents a factor of 32. Therefore, the difference in two whole numbers of the magnitude means that an earthquake is 1,000 times stronger. For example, a 7.0 magnitude earthquake releases 1,000 times more energy than a 5.0 one. (An excellent article in the Los Angeles Times on the history and current use of magnitude in earthquakes can be found here)

Relief map of Mexico. Credit: Carport, CC By 3.0One of the first facts to be reported about an earthquake is its magnitude. Many of us might be familiar with the term “Richter scale,” which was developed in the 1930s by two scientists at Caltech. The Richter scale was replaced in the 1970s by what is known as the “moment magnitude scale” that more accurately measures the impact of earthquakes.For non-geologists (such as ourselves) the difference between the Richter and moment magnitude scale could seem unnecessary to distinguish since they often report the same basic results. The most important thing we know about any measurement of the magnitude of an earthquake is that the bigger the number, the worse the earthquake.One useful point about the moment magnitude scale is that it is logarithmic, where each whole number represents a factor of 32. Therefore, the difference in two whole numbers of the magnitude means that an earthquake is 1,000 times stronger. For example, a 7.0 magnitude earthquake releases 1,000 times more energy than a 5.0 one. (An excellent article in the Los Angeles Times on the history and current use of magnitude in earthquakes can be found here) Space-based satellites can monitor Earth's changing surface, and map earthquakes, such as the one above in Pakistan from 2012. Credit: NASA/GSFC/METI/ERSDAC/JAROS, and U.S./Japan ASTER Science TeamThe word “magnitude” means many things, including “great extent” and “importance” and a “basis for comparison” as well as the language used to describe the extent to which an earthquake can cause harm.We chose the term “magnitude” for the title of our latest book for all of those definitions and uses. We are avid believers that science intersects with our daily lives in a host of ways that many of us might overlook. One of our goals in writing popular books is to help show that there is no “church and state” separation, if you will, between those who are affected by science and those who aren’t (be it a natural disaster, a new farming technique, or a different kind of medicine).We cannot control when the ground beneath us shakes. But we can do our best to stay informed on the latest scientific concepts, topics and terms. It is one small way that we can improve responses to whatever natural or human-made challenges we might face. To use a clichéd phrase, it is how we can best begin to understand the magnitude of a situation. A version of this blog was also published on HuffPost

Space-based satellites can monitor Earth's changing surface, and map earthquakes, such as the one above in Pakistan from 2012. Credit: NASA/GSFC/METI/ERSDAC/JAROS, and U.S./Japan ASTER Science TeamThe word “magnitude” means many things, including “great extent” and “importance” and a “basis for comparison” as well as the language used to describe the extent to which an earthquake can cause harm.We chose the term “magnitude” for the title of our latest book for all of those definitions and uses. We are avid believers that science intersects with our daily lives in a host of ways that many of us might overlook. One of our goals in writing popular books is to help show that there is no “church and state” separation, if you will, between those who are affected by science and those who aren’t (be it a natural disaster, a new farming technique, or a different kind of medicine).We cannot control when the ground beneath us shakes. But we can do our best to stay informed on the latest scientific concepts, topics and terms. It is one small way that we can improve responses to whatever natural or human-made challenges we might face. To use a clichéd phrase, it is how we can best begin to understand the magnitude of a situation. A version of this blog was also published on HuffPost

Published on September 23, 2017 05:45

September 11, 2017

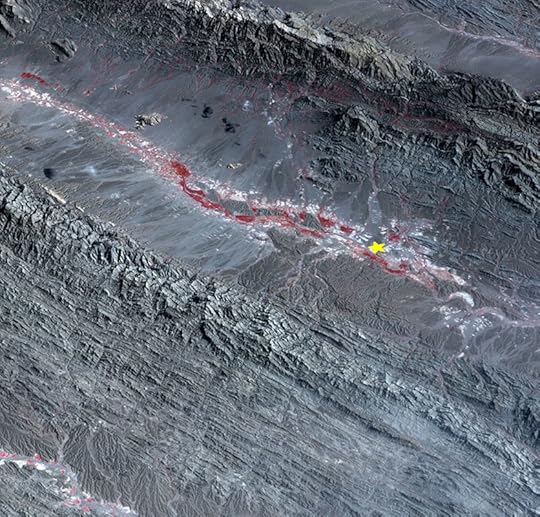

Cassini in Context: The Life and Death of a Space Traveler

On Friday, September 15, 2017, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft will make one final maneuver and then plummet into the planet Saturn. This kamikaze mission is not for show or spectacle, but for science. The Cassini mission was launched into space in 1997 and spent nearly the next seven years traveling to Saturn, the second largest planet in the Solar System and the sixth planet from the Sun. Before Cassini, scientists had just relatively brief glimpses of this amazing gas giant planet from flybys from NASA’s Pioneer and Voyager missions launched decades ago.It is no exaggeration that Cassini has revolutionized our understanding of Saturn and its fascinating moons. Read how on our latest blog on the Huffington Postand leave a comment here!

On Friday, September 15, 2017, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft will make one final maneuver and then plummet into the planet Saturn. This kamikaze mission is not for show or spectacle, but for science. The Cassini mission was launched into space in 1997 and spent nearly the next seven years traveling to Saturn, the second largest planet in the Solar System and the sixth planet from the Sun. Before Cassini, scientists had just relatively brief glimpses of this amazing gas giant planet from flybys from NASA’s Pioneer and Voyager missions launched decades ago.It is no exaggeration that Cassini has revolutionized our understanding of Saturn and its fascinating moons. Read how on our latest blog on the Huffington Postand leave a comment here!

Published on September 11, 2017 15:57

August 30, 2017

Why Understanding Scale Is Vital, Not Just For Science, But For Everyone

This week, Hurricane Harvey has seemingly exhausted every superlative that can be associated with a storm. Words like “catastrophic” and “historic” and “disastrous” are just some of those being used to try to explain what is happening in Texas and Louisiana. In today’s society, we can virtually watch such events unfold through the portal of social media. We often can’t really know the horrors or the suffering that are being experienced by those who are living through something like Harvey. We can only try to comprehend and offer help, usually remotely and indirectly for those of us who live far away, where possible.But we need to understand what is happening and the scale of the event to the best of our abilities. This applies not only to storms like Harvey, which could be growing in frequency and power due to climate change, but to many, many challenging topics in our world that are tossed about in the daily deluge of news. We live in a society where big numbers and large concepts are thrown around on many critical topics. From the economy to the environment, from medicine to manufacturing, and from politics to polymers, we are bombarded with facts and figures that can feel meaningless without context.In our latest blog post on Forbes "Starts With a Bang," we've sketched out some of our thoughts on the importance of understanding scale. Please read and comment below. https://www.forbes.com/sites/startswithabang/2017/08/30/why-understanding-scale-is-vital-not-just-for-science-but-for-everyoneImage credit: NASA

This week, Hurricane Harvey has seemingly exhausted every superlative that can be associated with a storm. Words like “catastrophic” and “historic” and “disastrous” are just some of those being used to try to explain what is happening in Texas and Louisiana. In today’s society, we can virtually watch such events unfold through the portal of social media. We often can’t really know the horrors or the suffering that are being experienced by those who are living through something like Harvey. We can only try to comprehend and offer help, usually remotely and indirectly for those of us who live far away, where possible.But we need to understand what is happening and the scale of the event to the best of our abilities. This applies not only to storms like Harvey, which could be growing in frequency and power due to climate change, but to many, many challenging topics in our world that are tossed about in the daily deluge of news. We live in a society where big numbers and large concepts are thrown around on many critical topics. From the economy to the environment, from medicine to manufacturing, and from politics to polymers, we are bombarded with facts and figures that can feel meaningless without context.In our latest blog post on Forbes "Starts With a Bang," we've sketched out some of our thoughts on the importance of understanding scale. Please read and comment below. https://www.forbes.com/sites/startswithabang/2017/08/30/why-understanding-scale-is-vital-not-just-for-science-but-for-everyoneImage credit: NASA

Published on August 30, 2017 08:45

August 24, 2017

Standing Up for Science in the Shadow of the Eclipse

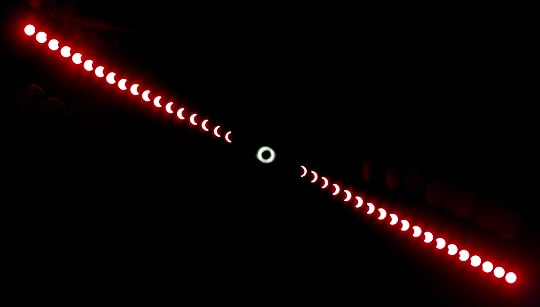

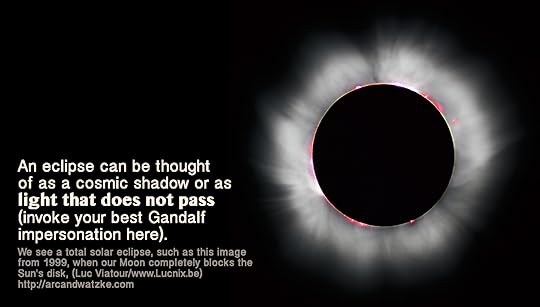

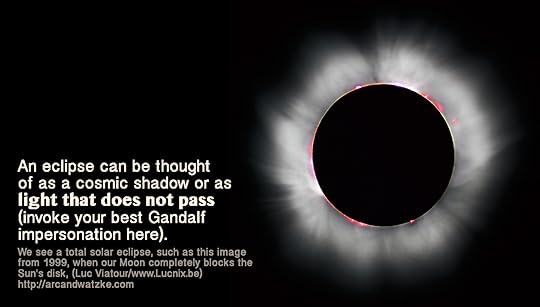

Megan and I both travelled for our day jobs to areas of totality for the recent solar eclipse on August 21st (me to Charleston, SC and Megan to Sun Valley, ID). Megan had a conference to work at and I had a talk to give. The eclipse affected both of us profoundly. Our latest piece in the Huffington Post is just one result of that experience. We hope you enjoy it, and please leave a comment. Additionally this week, we received the first advance copies of our latest book "Magnitude!" See photos and notes on our Instagram pages if you're interested. And many thanks to Jason Major who was with me in Charleston for letting me use his eclipse photos! Photo Credit: Jason Major, https://lightsinthedark.com Today, a growing number of people believe that the Earth is flat and that gravity is a hoax. People are aggressively questioning the legitimacy of climate change and the effectiveness of vaccines. We live in an age where the concept of “fact” is debatable. For people who have spent their careers conducting and, in our case, communicating the value of science, this is a frightening notion.But it also feels like a rallying cry, challenging us to not give up defending science and attempting to connect with everyone who will listen about its discoveries, impacts, and importance. Enter this week’s recent total solar eclipse, which arrived in North America to the wonder of millions on August 21. This was a rare moment to convince new audiences of not only the beauty of the natural world, but to help explain the scientific method that underpins this incredible natural phenomenon.Many of our ancestors saw total solar eclipses as harbingers of doom or destruction. The word “eclipse” comes from the ancient Greek “ekleipsis,” meaning “abandonment.” Homer referred to a total solar eclipse in the Odyssey, writing that “the sun has perished out of heaven, and an evil mist has overspread the world.” The Sun-worshiping Egyptians never recorded eclipses, leading to a theory that they considered eclipses as too evil to even document. Earlier Hindus wrote about a mythological demon that flew through the sky to swallow up the Sun, while Chinese mythology includes stories of a dragon that would devour the Sun.It was useful, if not comforting, to create mythological explanations for why the Sun would disappear, why the birds would stop chirping, why the nocturnal animals would awaken in the middle of the day, and why the winds would suddenly pick up and then, just as suddenly, die.The science of eclipses, however, can be explained by a relatively basic scientific concept: the shadow.Read the rest of the article at the Huffington Post.

Photo Credit: Jason Major, https://lightsinthedark.com Today, a growing number of people believe that the Earth is flat and that gravity is a hoax. People are aggressively questioning the legitimacy of climate change and the effectiveness of vaccines. We live in an age where the concept of “fact” is debatable. For people who have spent their careers conducting and, in our case, communicating the value of science, this is a frightening notion.But it also feels like a rallying cry, challenging us to not give up defending science and attempting to connect with everyone who will listen about its discoveries, impacts, and importance. Enter this week’s recent total solar eclipse, which arrived in North America to the wonder of millions on August 21. This was a rare moment to convince new audiences of not only the beauty of the natural world, but to help explain the scientific method that underpins this incredible natural phenomenon.Many of our ancestors saw total solar eclipses as harbingers of doom or destruction. The word “eclipse” comes from the ancient Greek “ekleipsis,” meaning “abandonment.” Homer referred to a total solar eclipse in the Odyssey, writing that “the sun has perished out of heaven, and an evil mist has overspread the world.” The Sun-worshiping Egyptians never recorded eclipses, leading to a theory that they considered eclipses as too evil to even document. Earlier Hindus wrote about a mythological demon that flew through the sky to swallow up the Sun, while Chinese mythology includes stories of a dragon that would devour the Sun.It was useful, if not comforting, to create mythological explanations for why the Sun would disappear, why the birds would stop chirping, why the nocturnal animals would awaken in the middle of the day, and why the winds would suddenly pick up and then, just as suddenly, die.The science of eclipses, however, can be explained by a relatively basic scientific concept: the shadow.Read the rest of the article at the Huffington Post.

Photo Credit: Jason Major, https://lightsinthedark.com Today, a growing number of people believe that the Earth is flat and that gravity is a hoax. People are aggressively questioning the legitimacy of climate change and the effectiveness of vaccines. We live in an age where the concept of “fact” is debatable. For people who have spent their careers conducting and, in our case, communicating the value of science, this is a frightening notion.But it also feels like a rallying cry, challenging us to not give up defending science and attempting to connect with everyone who will listen about its discoveries, impacts, and importance. Enter this week’s recent total solar eclipse, which arrived in North America to the wonder of millions on August 21. This was a rare moment to convince new audiences of not only the beauty of the natural world, but to help explain the scientific method that underpins this incredible natural phenomenon.Many of our ancestors saw total solar eclipses as harbingers of doom or destruction. The word “eclipse” comes from the ancient Greek “ekleipsis,” meaning “abandonment.” Homer referred to a total solar eclipse in the Odyssey, writing that “the sun has perished out of heaven, and an evil mist has overspread the world.” The Sun-worshiping Egyptians never recorded eclipses, leading to a theory that they considered eclipses as too evil to even document. Earlier Hindus wrote about a mythological demon that flew through the sky to swallow up the Sun, while Chinese mythology includes stories of a dragon that would devour the Sun.It was useful, if not comforting, to create mythological explanations for why the Sun would disappear, why the birds would stop chirping, why the nocturnal animals would awaken in the middle of the day, and why the winds would suddenly pick up and then, just as suddenly, die.The science of eclipses, however, can be explained by a relatively basic scientific concept: the shadow.Read the rest of the article at the Huffington Post.

Photo Credit: Jason Major, https://lightsinthedark.com Today, a growing number of people believe that the Earth is flat and that gravity is a hoax. People are aggressively questioning the legitimacy of climate change and the effectiveness of vaccines. We live in an age where the concept of “fact” is debatable. For people who have spent their careers conducting and, in our case, communicating the value of science, this is a frightening notion.But it also feels like a rallying cry, challenging us to not give up defending science and attempting to connect with everyone who will listen about its discoveries, impacts, and importance. Enter this week’s recent total solar eclipse, which arrived in North America to the wonder of millions on August 21. This was a rare moment to convince new audiences of not only the beauty of the natural world, but to help explain the scientific method that underpins this incredible natural phenomenon.Many of our ancestors saw total solar eclipses as harbingers of doom or destruction. The word “eclipse” comes from the ancient Greek “ekleipsis,” meaning “abandonment.” Homer referred to a total solar eclipse in the Odyssey, writing that “the sun has perished out of heaven, and an evil mist has overspread the world.” The Sun-worshiping Egyptians never recorded eclipses, leading to a theory that they considered eclipses as too evil to even document. Earlier Hindus wrote about a mythological demon that flew through the sky to swallow up the Sun, while Chinese mythology includes stories of a dragon that would devour the Sun.It was useful, if not comforting, to create mythological explanations for why the Sun would disappear, why the birds would stop chirping, why the nocturnal animals would awaken in the middle of the day, and why the winds would suddenly pick up and then, just as suddenly, die.The science of eclipses, however, can be explained by a relatively basic scientific concept: the shadow.Read the rest of the article at the Huffington Post.

Published on August 24, 2017 15:18

August 11, 2017

Women Who Chase the Sun

The total solar eclipse that will take place over North America in a couple of weeks is a chance for millions of people to experience an exciting event (with proper viewing glasses to protect our sensitive eyes, of course!). Given the population’s demographics, it stands to reason that about half of those who will be under the spectacle of totality will be women.This is rather appropriate to reflect on. To quote the title of the best seller by Nicolas Kristof and Sheryl Dunn (by way of Mao Zedong), “women hold up half the sky.” But women have been doing far more than just shouldering the weight of the heavens over the years. We have been actively studying the Sun, Moon, stars and beyond for millennia. Women have played a key role in observing solar eclipses and expanding our understanding of how the Sun, our nearest star, works.In our latest piece on the Huffington Post, we provide a brief introduction to just a few of the many women who have chased the Sun for the benefit of all, from antiquity through present day. We encourage readers to leave comments on our article with other women they know that chase the Sun. We've already had a few great suggestions!http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/women-who-chase-the-sun_us_598a38e4e4b0f25bdfb32058Additionally, if you find yourself on Instagram these days, stop over to our accounts, @kimberlykowal and @meganwatzke to say hi! We've been experimenting more on this really fun platform lately. Megan recently started her account, and is now in full swing as a 'grammer. And Kim has been showcasing the type of things she gets to do each day in her InstaStories section, from talks and events to writing and creating. You can also catch up with her posts on this web site at http://arcandwatzke.com/instagram

The total solar eclipse that will take place over North America in a couple of weeks is a chance for millions of people to experience an exciting event (with proper viewing glasses to protect our sensitive eyes, of course!). Given the population’s demographics, it stands to reason that about half of those who will be under the spectacle of totality will be women.This is rather appropriate to reflect on. To quote the title of the best seller by Nicolas Kristof and Sheryl Dunn (by way of Mao Zedong), “women hold up half the sky.” But women have been doing far more than just shouldering the weight of the heavens over the years. We have been actively studying the Sun, Moon, stars and beyond for millennia. Women have played a key role in observing solar eclipses and expanding our understanding of how the Sun, our nearest star, works.In our latest piece on the Huffington Post, we provide a brief introduction to just a few of the many women who have chased the Sun for the benefit of all, from antiquity through present day. We encourage readers to leave comments on our article with other women they know that chase the Sun. We've already had a few great suggestions!http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/women-who-chase-the-sun_us_598a38e4e4b0f25bdfb32058Additionally, if you find yourself on Instagram these days, stop over to our accounts, @kimberlykowal and @meganwatzke to say hi! We've been experimenting more on this really fun platform lately. Megan recently started her account, and is now in full swing as a 'grammer. And Kim has been showcasing the type of things she gets to do each day in her InstaStories section, from talks and events to writing and creating. You can also catch up with her posts on this web site at http://arcandwatzke.com/instagram

Published on August 11, 2017 10:41

August 1, 2017

Goodreads Giveaway!

In honor of the upcoming total solar eclipse (on August 21st, 2017 ☀️

Published on August 01, 2017 04:52

Capturing the Universe, on Paper:

A Q&A with Megan

The following few questions are some of the most frequent questions I get when talking to people about what I do. I hope you enjoy finding out a little more about me:What exactly do you do? My career can be described several different ways, but the short answer is I write about science. For my day job, I write about astronomy and astrophysics related to NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory for the public. This means I work on press releases, blog posts, material for the website, short articles, long articles, video scripts, you name it.On the side, I write popular science books. The first one was exclusively about space (“Your Ticket to the Universe: A Guide to Exploring the Cosmos”) and we also co-authored one with Travis Rector about how images from space are made (“Coloring the Universe: An Insider’s Guide to Making Spectacular Images of Space”.) Our other two books venture beyond space, though there’s some astronomy in there. “Light: The Visible Spectrum and Beyond”) had lots of different kinds of science in it and our upcoming book, “Magnitude: The Scale of the Universe,” will likewise cover many different topics and disciplines.How did you get into your career?When I was growing up and into high school, I liked a lot of different subjects including history and literature. However, I always had a pull toward science. When it came time to go to college, I deliberately picked a large enough school that would have the full suite of options for me, including astronomy. While I did enjoy majoring in that at the University of Michigan, I knew by my junior year that I didn’t want to pursue a Ph.D. in astrophysics.Instead, I found the science journalism program at Boston University, which was a great fit. Since I had spent my four years in college doing things like problem sets and very little writing, it was just what I needed. The BU program really taught me how to write and what journalism is all about. Through one of my professors, I was able to land my first job as a public affairs specialist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, which then led to my current position.

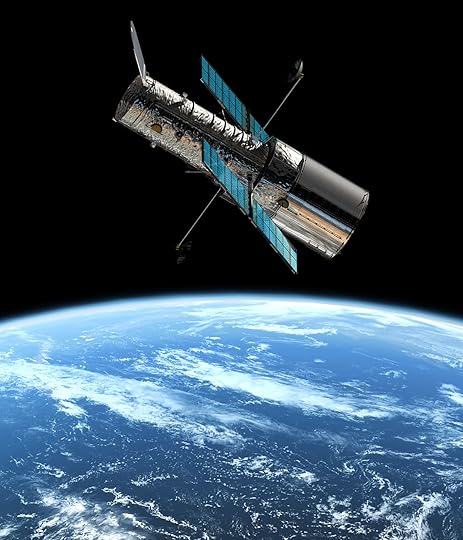

My career can be described several different ways, but the short answer is I write about science. For my day job, I write about astronomy and astrophysics related to NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory for the public. This means I work on press releases, blog posts, material for the website, short articles, long articles, video scripts, you name it.On the side, I write popular science books. The first one was exclusively about space (“Your Ticket to the Universe: A Guide to Exploring the Cosmos”) and we also co-authored one with Travis Rector about how images from space are made (“Coloring the Universe: An Insider’s Guide to Making Spectacular Images of Space”.) Our other two books venture beyond space, though there’s some astronomy in there. “Light: The Visible Spectrum and Beyond”) had lots of different kinds of science in it and our upcoming book, “Magnitude: The Scale of the Universe,” will likewise cover many different topics and disciplines.How did you get into your career?When I was growing up and into high school, I liked a lot of different subjects including history and literature. However, I always had a pull toward science. When it came time to go to college, I deliberately picked a large enough school that would have the full suite of options for me, including astronomy. While I did enjoy majoring in that at the University of Michigan, I knew by my junior year that I didn’t want to pursue a Ph.D. in astrophysics.Instead, I found the science journalism program at Boston University, which was a great fit. Since I had spent my four years in college doing things like problem sets and very little writing, it was just what I needed. The BU program really taught me how to write and what journalism is all about. Through one of my professors, I was able to land my first job as a public affairs specialist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, which then led to my current position. CfA. Credit: John Phelan, CC by 3.0What’s it like to work for NASA?The first thing to understand is that NASA is a huge agency. There are multiple centers scattered around the country – from New York City to Alabama to California. Many people work on what NASA’s best known for: human space flight. However, there are thousands of people who work on different aspects of science, engineering, technology, and various ways to support these efforts. On top of that, NASA contracts with universities, industries, and other federal agencies to do all that they do. I work on one mission in the astrophysics division, but there are many, many aspects to NASA that I don’t have any first-hand experience with. I do interact with NASA HQ, which is Washington, DC, but I don’t physically work at a NASA center. Since Chandra is controlled and operated by the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, I think our workplace has more of an academic feel than much of NASA.I’ve heard of Hubble, but not Chandra. Why not?Chandra is one of NASA’s so-called Great Observatories, which means it’s a sister mission to Hubble along with Spitzer and Compton (no longer operating). The Great Observatories were designed as a set – each looking at a different kind of light. Hubble first became famous partly because it didn’t work as it should after it launched. (It didn’t help during that time that “Hubble” rhymed with “trouble”.) For a while, it seemed like a multi-billion dollar mistake that NASA had to deal with. Of course, the story took a dramatic turn for the better when astronauts bravely went up and fixed the telescope. After that, there was a flood of amazing data that came back and Hubble has been famous ever since. In fact, I would argue that the name “Hubble” is synonymous with “telescope” the way that “Coke” is tied to “soda” or “Kleenex” is to “tissue.” It’s almost become its own brand name for all things dealing with space.No other telescope will likely ever have the name recognition that Hubble does, but that doesn’t mean the public isn’t fascinated by the science produced by Chandra and others. We get major coverage for many of our discoveries that cover things like black holes, exploded stars, dark matter, etc. It’s just that many people might not remember the name of Chandra, which is fine with me as long as they are excited by the science itself!

CfA. Credit: John Phelan, CC by 3.0What’s it like to work for NASA?The first thing to understand is that NASA is a huge agency. There are multiple centers scattered around the country – from New York City to Alabama to California. Many people work on what NASA’s best known for: human space flight. However, there are thousands of people who work on different aspects of science, engineering, technology, and various ways to support these efforts. On top of that, NASA contracts with universities, industries, and other federal agencies to do all that they do. I work on one mission in the astrophysics division, but there are many, many aspects to NASA that I don’t have any first-hand experience with. I do interact with NASA HQ, which is Washington, DC, but I don’t physically work at a NASA center. Since Chandra is controlled and operated by the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, I think our workplace has more of an academic feel than much of NASA.I’ve heard of Hubble, but not Chandra. Why not?Chandra is one of NASA’s so-called Great Observatories, which means it’s a sister mission to Hubble along with Spitzer and Compton (no longer operating). The Great Observatories were designed as a set – each looking at a different kind of light. Hubble first became famous partly because it didn’t work as it should after it launched. (It didn’t help during that time that “Hubble” rhymed with “trouble”.) For a while, it seemed like a multi-billion dollar mistake that NASA had to deal with. Of course, the story took a dramatic turn for the better when astronauts bravely went up and fixed the telescope. After that, there was a flood of amazing data that came back and Hubble has been famous ever since. In fact, I would argue that the name “Hubble” is synonymous with “telescope” the way that “Coke” is tied to “soda” or “Kleenex” is to “tissue.” It’s almost become its own brand name for all things dealing with space.No other telescope will likely ever have the name recognition that Hubble does, but that doesn’t mean the public isn’t fascinated by the science produced by Chandra and others. We get major coverage for many of our discoveries that cover things like black holes, exploded stars, dark matter, etc. It’s just that many people might not remember the name of Chandra, which is fine with me as long as they are excited by the science itself!  Hubble Space Telescope. Credit: NASAYour job sounds really fun, but I could never imagine being able to do that.This is more of a comment than a question, but I get it a lot – especially from women, which makes me want to tear my hair out. The implication for comments like this is often that science is too hard for many people, or at least large groups who don’t identify as being “science people.”The truth is that our society has done a fantastic job of convincing far too many of us that science is something only done by a select few (this often is restricted to white men). One main goal of my career is to change that perception. Science is for all of us. Period end. It affects everyone and, perhaps more importantly, it can be done and understood by anyone. This doesn’t mean that it’s easy, but then again, neither is being a professional musician or a master carpenter or many, many disciplines. I hope that the reputation of exclusivity that has been perpetuated about science can one day be permanently dismantled. If I can play a small role in that, I’ll be thrilled.-Megan Watzke

Hubble Space Telescope. Credit: NASAYour job sounds really fun, but I could never imagine being able to do that.This is more of a comment than a question, but I get it a lot – especially from women, which makes me want to tear my hair out. The implication for comments like this is often that science is too hard for many people, or at least large groups who don’t identify as being “science people.”The truth is that our society has done a fantastic job of convincing far too many of us that science is something only done by a select few (this often is restricted to white men). One main goal of my career is to change that perception. Science is for all of us. Period end. It affects everyone and, perhaps more importantly, it can be done and understood by anyone. This doesn’t mean that it’s easy, but then again, neither is being a professional musician or a master carpenter or many, many disciplines. I hope that the reputation of exclusivity that has been perpetuated about science can one day be permanently dismantled. If I can play a small role in that, I’ll be thrilled.-Megan Watzke

My career can be described several different ways, but the short answer is I write about science. For my day job, I write about astronomy and astrophysics related to NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory for the public. This means I work on press releases, blog posts, material for the website, short articles, long articles, video scripts, you name it.On the side, I write popular science books. The first one was exclusively about space (“Your Ticket to the Universe: A Guide to Exploring the Cosmos”) and we also co-authored one with Travis Rector about how images from space are made (“Coloring the Universe: An Insider’s Guide to Making Spectacular Images of Space”.) Our other two books venture beyond space, though there’s some astronomy in there. “Light: The Visible Spectrum and Beyond”) had lots of different kinds of science in it and our upcoming book, “Magnitude: The Scale of the Universe,” will likewise cover many different topics and disciplines.How did you get into your career?When I was growing up and into high school, I liked a lot of different subjects including history and literature. However, I always had a pull toward science. When it came time to go to college, I deliberately picked a large enough school that would have the full suite of options for me, including astronomy. While I did enjoy majoring in that at the University of Michigan, I knew by my junior year that I didn’t want to pursue a Ph.D. in astrophysics.Instead, I found the science journalism program at Boston University, which was a great fit. Since I had spent my four years in college doing things like problem sets and very little writing, it was just what I needed. The BU program really taught me how to write and what journalism is all about. Through one of my professors, I was able to land my first job as a public affairs specialist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, which then led to my current position.

My career can be described several different ways, but the short answer is I write about science. For my day job, I write about astronomy and astrophysics related to NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory for the public. This means I work on press releases, blog posts, material for the website, short articles, long articles, video scripts, you name it.On the side, I write popular science books. The first one was exclusively about space (“Your Ticket to the Universe: A Guide to Exploring the Cosmos”) and we also co-authored one with Travis Rector about how images from space are made (“Coloring the Universe: An Insider’s Guide to Making Spectacular Images of Space”.) Our other two books venture beyond space, though there’s some astronomy in there. “Light: The Visible Spectrum and Beyond”) had lots of different kinds of science in it and our upcoming book, “Magnitude: The Scale of the Universe,” will likewise cover many different topics and disciplines.How did you get into your career?When I was growing up and into high school, I liked a lot of different subjects including history and literature. However, I always had a pull toward science. When it came time to go to college, I deliberately picked a large enough school that would have the full suite of options for me, including astronomy. While I did enjoy majoring in that at the University of Michigan, I knew by my junior year that I didn’t want to pursue a Ph.D. in astrophysics.Instead, I found the science journalism program at Boston University, which was a great fit. Since I had spent my four years in college doing things like problem sets and very little writing, it was just what I needed. The BU program really taught me how to write and what journalism is all about. Through one of my professors, I was able to land my first job as a public affairs specialist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, which then led to my current position. CfA. Credit: John Phelan, CC by 3.0What’s it like to work for NASA?The first thing to understand is that NASA is a huge agency. There are multiple centers scattered around the country – from New York City to Alabama to California. Many people work on what NASA’s best known for: human space flight. However, there are thousands of people who work on different aspects of science, engineering, technology, and various ways to support these efforts. On top of that, NASA contracts with universities, industries, and other federal agencies to do all that they do. I work on one mission in the astrophysics division, but there are many, many aspects to NASA that I don’t have any first-hand experience with. I do interact with NASA HQ, which is Washington, DC, but I don’t physically work at a NASA center. Since Chandra is controlled and operated by the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, I think our workplace has more of an academic feel than much of NASA.I’ve heard of Hubble, but not Chandra. Why not?Chandra is one of NASA’s so-called Great Observatories, which means it’s a sister mission to Hubble along with Spitzer and Compton (no longer operating). The Great Observatories were designed as a set – each looking at a different kind of light. Hubble first became famous partly because it didn’t work as it should after it launched. (It didn’t help during that time that “Hubble” rhymed with “trouble”.) For a while, it seemed like a multi-billion dollar mistake that NASA had to deal with. Of course, the story took a dramatic turn for the better when astronauts bravely went up and fixed the telescope. After that, there was a flood of amazing data that came back and Hubble has been famous ever since. In fact, I would argue that the name “Hubble” is synonymous with “telescope” the way that “Coke” is tied to “soda” or “Kleenex” is to “tissue.” It’s almost become its own brand name for all things dealing with space.No other telescope will likely ever have the name recognition that Hubble does, but that doesn’t mean the public isn’t fascinated by the science produced by Chandra and others. We get major coverage for many of our discoveries that cover things like black holes, exploded stars, dark matter, etc. It’s just that many people might not remember the name of Chandra, which is fine with me as long as they are excited by the science itself!

CfA. Credit: John Phelan, CC by 3.0What’s it like to work for NASA?The first thing to understand is that NASA is a huge agency. There are multiple centers scattered around the country – from New York City to Alabama to California. Many people work on what NASA’s best known for: human space flight. However, there are thousands of people who work on different aspects of science, engineering, technology, and various ways to support these efforts. On top of that, NASA contracts with universities, industries, and other federal agencies to do all that they do. I work on one mission in the astrophysics division, but there are many, many aspects to NASA that I don’t have any first-hand experience with. I do interact with NASA HQ, which is Washington, DC, but I don’t physically work at a NASA center. Since Chandra is controlled and operated by the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, I think our workplace has more of an academic feel than much of NASA.I’ve heard of Hubble, but not Chandra. Why not?Chandra is one of NASA’s so-called Great Observatories, which means it’s a sister mission to Hubble along with Spitzer and Compton (no longer operating). The Great Observatories were designed as a set – each looking at a different kind of light. Hubble first became famous partly because it didn’t work as it should after it launched. (It didn’t help during that time that “Hubble” rhymed with “trouble”.) For a while, it seemed like a multi-billion dollar mistake that NASA had to deal with. Of course, the story took a dramatic turn for the better when astronauts bravely went up and fixed the telescope. After that, there was a flood of amazing data that came back and Hubble has been famous ever since. In fact, I would argue that the name “Hubble” is synonymous with “telescope” the way that “Coke” is tied to “soda” or “Kleenex” is to “tissue.” It’s almost become its own brand name for all things dealing with space.No other telescope will likely ever have the name recognition that Hubble does, but that doesn’t mean the public isn’t fascinated by the science produced by Chandra and others. We get major coverage for many of our discoveries that cover things like black holes, exploded stars, dark matter, etc. It’s just that many people might not remember the name of Chandra, which is fine with me as long as they are excited by the science itself!  Hubble Space Telescope. Credit: NASAYour job sounds really fun, but I could never imagine being able to do that.This is more of a comment than a question, but I get it a lot – especially from women, which makes me want to tear my hair out. The implication for comments like this is often that science is too hard for many people, or at least large groups who don’t identify as being “science people.”The truth is that our society has done a fantastic job of convincing far too many of us that science is something only done by a select few (this often is restricted to white men). One main goal of my career is to change that perception. Science is for all of us. Period end. It affects everyone and, perhaps more importantly, it can be done and understood by anyone. This doesn’t mean that it’s easy, but then again, neither is being a professional musician or a master carpenter or many, many disciplines. I hope that the reputation of exclusivity that has been perpetuated about science can one day be permanently dismantled. If I can play a small role in that, I’ll be thrilled.-Megan Watzke

Hubble Space Telescope. Credit: NASAYour job sounds really fun, but I could never imagine being able to do that.This is more of a comment than a question, but I get it a lot – especially from women, which makes me want to tear my hair out. The implication for comments like this is often that science is too hard for many people, or at least large groups who don’t identify as being “science people.”The truth is that our society has done a fantastic job of convincing far too many of us that science is something only done by a select few (this often is restricted to white men). One main goal of my career is to change that perception. Science is for all of us. Period end. It affects everyone and, perhaps more importantly, it can be done and understood by anyone. This doesn’t mean that it’s easy, but then again, neither is being a professional musician or a master carpenter or many, many disciplines. I hope that the reputation of exclusivity that has been perpetuated about science can one day be permanently dismantled. If I can play a small role in that, I’ll be thrilled.-Megan Watzke

Published on August 01, 2017 04:37

July 31, 2017

New Giveaway of LIGHT

Just in time for the upcoming Total Solar Eclipse (which is on August 21, 2017) we are sharing this fun Goodreads Giveaway! "Light: the Visible Spectrum and Beyond" is a great read ahead of the eclipse. Enter now and share the giveaway with your friends:

https://www.goodreads.com/giveaway/sh...

https://www.goodreads.com/giveaway/sh...

Published on July 31, 2017 12:24

July 10, 2017

Celebrating the Light, the Dark and the Total Solar Eclipse

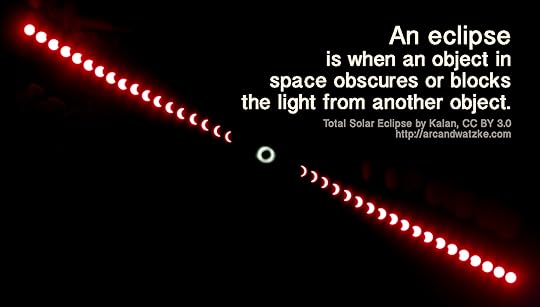

(Pictured: 2008 solar eclipse from Russia. (Kalan, CC BY 3.0))On August 21st, a total solar eclipse will be visible from Oregon to South Carolina. This event will be a once-in-a-lifetime event for millions in the United States who will get to experience what happens, for a brief period of time, when day turns to night - assuming the weather cooperates of course. The last time the U.S. had such a coast-to-coast view of a total solar eclipse was almost 100 years ago. There will be many articles about the majesty and importance of total solar eclipses in the coming weeks, leading up to the momentous event. We have written a list, however, that outlines perhaps lesser-known things about the phenomenon that makes total solar eclipses possible: light. From why shadows are important in science to the many different kinds of light we use in science today, we've outlined a few fun things to consider before our Sun temporarily goes dark on August 21st, 2017.

(Pictured: 2008 solar eclipse from Russia. (Kalan, CC BY 3.0))On August 21st, a total solar eclipse will be visible from Oregon to South Carolina. This event will be a once-in-a-lifetime event for millions in the United States who will get to experience what happens, for a brief period of time, when day turns to night - assuming the weather cooperates of course. The last time the U.S. had such a coast-to-coast view of a total solar eclipse was almost 100 years ago. There will be many articles about the majesty and importance of total solar eclipses in the coming weeks, leading up to the momentous event. We have written a list, however, that outlines perhaps lesser-known things about the phenomenon that makes total solar eclipses possible: light. From why shadows are important in science to the many different kinds of light we use in science today, we've outlined a few fun things to consider before our Sun temporarily goes dark on August 21st, 2017. Pictured: Solar Eclipse by Kurt Kulac on 2006-03-29, CC-BY-SA-2.5 and GNU FDLYou can read the full list in our article at the HuffPost. To help kick off our early celebrations of the light (and the dark) of the upcoming eclipse, we have also posted a new #AmazonGiveaway! Enter for a chance to win a free copy of "Light: The Visible Spectrum and Beyond" (pictured below), no purchase necessary.

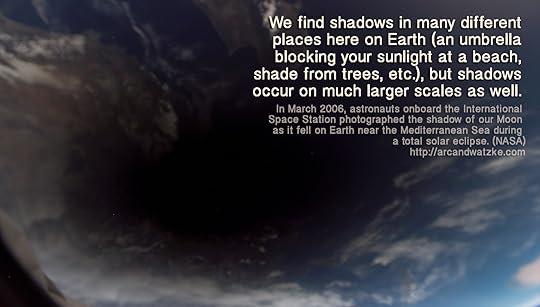

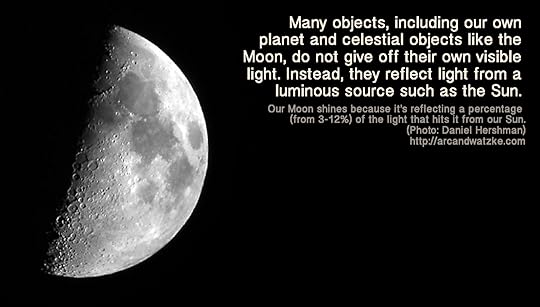

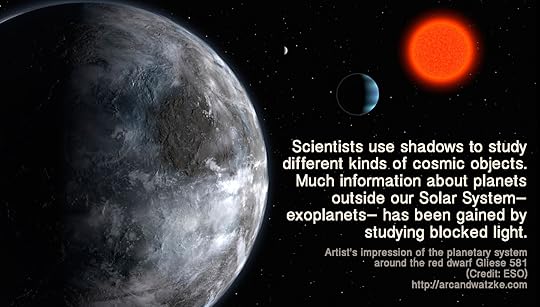

Pictured: Solar Eclipse by Kurt Kulac on 2006-03-29, CC-BY-SA-2.5 and GNU FDLYou can read the full list in our article at the HuffPost. To help kick off our early celebrations of the light (and the dark) of the upcoming eclipse, we have also posted a new #AmazonGiveaway! Enter for a chance to win a free copy of "Light: The Visible Spectrum and Beyond" (pictured below), no purchase necessary.  Through out this week of light and dark, we'll be posting shareable web graphics (like the one below) of our top ten tidbits on light on Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram, and Facebook, doing a second giveaway on Instagram, and generally having fun with one of our favorite topics - LIGHT.

Through out this week of light and dark, we'll be posting shareable web graphics (like the one below) of our top ten tidbits on light on Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram, and Facebook, doing a second giveaway on Instagram, and generally having fun with one of our favorite topics - LIGHT. Download more social media shareable graphics below!A solar eclipse like the one many in America will be able to experience this summer provides a great opportunity to reflect (pun intended!) on the wonders of light and what it does for us.-Kim & MeganDownload and share these free graphics to your favorite social media platforms:

Download more social media shareable graphics below!A solar eclipse like the one many in America will be able to experience this summer provides a great opportunity to reflect (pun intended!) on the wonders of light and what it does for us.-Kim & MeganDownload and share these free graphics to your favorite social media platforms:

Published on July 10, 2017 06:34