Justin Robinson's Blog, page 24

November 1, 2013

Lifetime Theater: Anna Nicole

Sex symbols are a link to the past, living screens upon which entire generations projected idealized beauty. By which I mean that they were the people your grandparents masturbated to. Yeah, I’m sure there’s a more highfalutin’ way to put it, but that’s what it comes down to in the end. If you want to strip away all the flowery language, all the pretensions to some higher state, and get right down to it, sex symbols get their status from folks shucking the oyster, or roughing up the suspect, to their image. Sometimes sex symbols last the test of time; I don’t know any man who doesn’t find Marilyn Monroe attractive. Sometimes they serve only to baffle future masturbators; I can’t wrap my head around anyone finding Julie Christie even slightly alluring. In every case, they are the fantasy sex partners of huge swaths of dead people, and for that, they are fascinating.

Critics would say our sex symbols are growing ever tawdrier. It’s hard to argue, what with Kim Kardashian making the leap specifically on the back of what amounts to home movie porn, and numerous other personalities following in her… well, not her footsteps. But you get the idea. And doing so with varying degrees of success — for every Paris Hilton, there’s a Farrah Abraham, and believe me, I hate coming up with a scenario where Paris Hilton is the positive example. The internet has a cheapening effect; by making everything ubiquitous (and by “everything” I mean boobs), it reduces the value of any one thing (by which I mean individual sets of boobs). Things were better in the Good Old Days, when women got famous for being virginal avatars of ultimate femininity, and would blush prettily at the slightest intimation of life’s more venal charms. This is, of course, utter bullshit.

Whenever someone speaks rapturously about the good old days, chances are that person is a) white b) wealthy c) heterosexual d) male e) running for office on the Republican ticket and f) blissfully ignorant of history. The Good Old Days never really existed, and this week’s Lifetime Theater, the biopic of zaftig sex bomb from the early ‘90s Anna Nicole, sets out to unintentionally prove just that. When she burst on the scene, first in the pages of Playboy then as the face of Guess, Anna Nicole Smith was hailed as the next coming of Marilyn Monroe. Vince Vega would have snottily clarified that Anna was far more Jayne Mansfield, but the point was that she was a curvier beauty than was in vogue at the time, and with the right makeup and lighting, could conjure comparison to the screen goddesses of yesteryear. Also, a lot of people masturbated to her.

Critics will point out that Anna Nicole was really not much more than a hillbilly, an ex-stripper and gold-digger, an attention whore and (and those who leveled this last criticism seemed to think it was the only one of value for the entire gender) Not That Hot. They pined for the refined beauty for Smith’s inspiration, the effete socialite Marilyn Monroe. You know, skipping that part about how Marilyn posed in the same girlie mag that gave Smith her start, and later died in much the same way. Monroe was also magnetic and lovely, with a screen presence so electrifying, when I saw her in All About Eve I instantly revealed the location of Liam Neeson’s kidnapped daughter. So the critics have a small point, but it’s important to look at the big picture.

Anna Nicole traces its eponymous heroine (Agnes Bruckner) from her ignoble beginnings in Mexia, Texas (named, I suspect, to win a bar bet) to international sex symbol, to sad joke, to tragic punchline. The film can’t quite decide exactly what Anna Nicole is, either. Her copious drug use is a major plot point (and bringing to mind images of Dewey Cox falling to the temptations of reefer) but at several points, it’s implied she’s faking it. In some cases, she’s shown to be playing to the cameras, and in others, she appears to be doing it for no discernible purpose. Most egregious is, after establishing that she’s on the wagon, she shows up to the Supreme Court apparently stoned, drunk or both, which would seem to be a terrible idea. For some reason, this biopic of a woman who seemed to slur more words than she spoke, who was famous for being a train wreck, and who later died from her addictions, tries to protect its subject’s nonexistent reputation.

This ambivalence extends toward her career path. While the film adopts a very tongue-clucking stance toward sex work, Anna Nicole’s breast implants and Playboy-fame are treated as triumphant steps toward international stardom. From the moment in the beginning when she breathlessly finds an issue of Playboy underneath her stepfather’s bed (while said stepfather sexually assaults her teenaged aunt in the other room — this film goes from zero to rape in two minutes, which might be a Lifetime record), she seems this as the way out of her present depressing life. She manages to use her centerfold as a springboard to become the face of Guess, and instantly pisses everything away by doing the most convincing Lindsay Lohan impression I’ve ever seen. The film hamhandedly gives us the reason for the downfall with the drugs and alcohol that make it possible for this woman to show her body, yet at the same time this exhibitionism is treated as a victory for the small town girl. Between 1992 and 1994, Anna Nicole could lay claim to being one of the most desired women on the planet, and the film rockets past the glory days, choosing instead to wallow in the misery on either end. Mary Harron, who directed this movie, also helmed the similar but vastly superior The Notorious Bettie Page, making Anna Nicole’s missteps that much stranger.

This undersells the film’s insanity. I was worried this would be some kind of drab biopic, with none of the sleazy voyeurism promised by the subject… until the appearance of my favorite character in the film, Ghost Anna Nicole. When Anna Nicole’s mom (Virginia Madsen, in one of the many overqualified cast members) throws the stepdad out for the aforementioned rapes, Ghost Anna Nicole appears to child Anna Nicole and promises fame, fortune, and earrings, because something physical never hurt. Ghost Anna Nicole appears at several times in the front half of the film, when our heroine is still going by her birth name, Vickie Lynn Hogan, egging her on whenever she has doubts over her career path. She’s Jiminy Cricket with a boob job, if Jiminy’s only advice to Pinocchio had been, “Don’t worry, kid! Everybody snorts PCP from time to time. Makes you feel great, and you can lift cars!” In the back half, as our heroine has become a shell of an addict with a career in pieces, Ghost Vickie Lynn appears with big waifish eyes as if to say, “Why did you believe that crazy bitch?”

The bulk of the runtime is given over to Anna Nicole’s relationship with her family. She has a son, Danny, from an early marriage, who grows up alongside her. As he matures, he gains a typical kid’s reaction to having a drugged-out embarrassing attention whore of a mother. As he ages further, he falls into the same trap she does, and ends up dying young in her hospital room. Her most famous relationship was with J. Howard Marshall (Martin Landau. No, seriously.), a Texas billionaire, sixty-two years Anna Nicole’s senior, who goes to a strip club against his wishes and ends up becoming instantly smitten with the balloon-breasted siren on the pole. The movie takes Anna Nicole at her word, that the relationship with J. Howard featured as much sex as a middle school dance and was more about security for her and her son once her career hit the skids. As though to prove it, she addresses him by the creepy nickname of Paw Paw, which made me want a shower every time she said it. J. Howard’s son, E. Pierce (Cary Elwes, who seems to exist only to impress upon all of us the cruelty of time) is portrayed as a sneering patrician, dead set against Anna Nicole’s livelihood simply because she is not his mother. Once J. Howard dies, the court proceedings, and the final act of our heroine’s life, begins.

This is heralded by the arrival in 1995 of Howard K. Stern (Adam Goldberg), a lawyer/agent who would have to improve greatly to qualify as merely sleazy. He finds Anna Nicole as a barely verbal junkie and sees a meal ticket in the making. He decides he’s going to make her a star the only way he knows how: by sticking her in as much cheap junk financed by as much shady foreign capital as he can. While Anna Nicole only brings up one of these, a trip to will show a depressing litany of increasing embarrassment. Howard is not done. His crowning achievement/crushing nadir comes in the form of The Anna Nicole Show, a reality series on E! that not only gave reality television a bad name, it will someday provide justification to the aliens who want to destroy our planet. With the sudden and incredible success of The Osbornes, every network was looking for another has-been celebrity whose life they could put onscreen. Anna Nicole’s attempt is famous — well, infamous — for being the most horrifying, voyeuristic trash of a subgenre consisting entirely of horrifying voyeuristic trash. In Anna Nicole’s version of events, she wasn’t a pill-addled wreck, but merely playing one. It’s the least convincing excuse since Eddie Murphy picked up that “hitchhiker.”

In true ambivalent fashion, the film treats even her ignominious death as a triumph. In full Ghost Anna Nicole mode (implying this was Ghost Anna Nicole’s aim all alone), she strides down a mirrored hallway, at the end of which a door opens to the snapping flashbulbs of cameras. Heaven is a red carpet? God, that is depressing and tawdry.

Filed under: Projected Pixels and Emulsion Tagged: Anna Nicole, Anna Nicole Smith, Lifetime, Lifetime Theater, Playboy, stripping, train wrecks

October 31, 2013

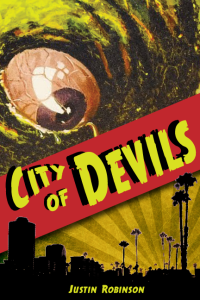

CITY OF DEVILS. 99 cents

http://www.candlemarkandgleam.com/sho...

And UNDEAD ON ARRIVAL, my hardboiled zombie detective novel is still free for the rest of the day!

http://www.amazon.com/Undead-on-Arriv...

October 30, 2013

UNDEAD ON ARRIVAL. Free.

Get it and be awesome.

http://www.amazon.com/Undead-on-Arriv...

October 25, 2013

Rules of Writing: Death or Lumberjack

Endings are hard.

Endings are important.

And because of this, endings are scary.

Let’s say you’re trying to end something long-form, say, a television series or a novel or a series of novels. You’ve written an story that spans hundreds or even thousands of pages, which is much longer than it would take to relate any of the real events that happened in your life. You’ve created characters so real you occasionally think they take over and write the story for you. But everything has an ending, and now it’s time for yours. Only you have to somehow pick the perfect option that ties up the story and the characters, but maybe not too much since a little ambiguity is necessary for the sake of realism. Granted, you’re never going to please everyone, but the goal is to fit the best ending to the story, no matter the ultimate mood, and trust that you will please the people who really get it. In essence, you’ve finished a gymnastics routine lasting months, but if you don’t stick the landing, you’re going to be stuck with scores of 2s and 3s. Unfair? Sure. The ending is what people remember. You can dodge a shaky beginning, you can survive a shitty middle, so long as you crush the ending. The best endings are at once unexpected and inevitable, which is a little like saying something should be both sexy and scabrous.

That is such a hard tightrope to walk (to completely butcher my sports-related metaphor), even some of the biggest and best out there shit the bed with alarming regularity. As much as I love Stephen King, a lot of his books have endings that leave something to be desired. For every Misery, there’s an Under the Dome. Horror makes truly satisfying endings difficult. Some people only like happy endings, and if your ending is too happy you’re doing horror wrong. And if you write creature horror, chances are the creature you’ve created to hunt the everyman heroes and heroines of the novel is so damn powerful that any attempt to put it away will come off as unrealistic. King often has to resort to desperation plays: the appeal to pity in Under the Dome or the bizarre rite in It. These will play differently based on personal preference, but for me they never quite fulfilled the promise from the beginning of the novel.

Unlike the show, which merely urinated on that promise.

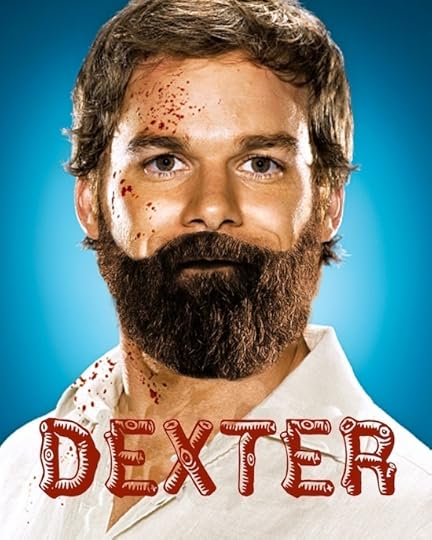

Because of the changes in the way we consume television shows, endings have taken on outsized importance in that media as well. Nowadays, people will often wait for shows to end before binge-watching the entire series. For this reason, a good series finale is vital to the ongoing life of a show. Think about it: how many people are going to recommend Dexter to their friends? And that’s what I’m really here to talk about. If you were following me on Twitter during the home stretch of Dexter, you know by now what I thought of the final season. If you don’t follow me on Twitter, I’m assuming you make your own dick jokes and don’t really need me to supply them. In any case, my view of Dexter roughly jibes with the critical consensus: that it was a decent show that flirted with greatness in the beginning, settled for being pulpy fun, and eventually degenerated into a pile of crap that I vowed to stop watching. Only I didn’t, and boy howdy do I regret it.

Dexter is a show that so thoroughly shit the bed of its ending, it’s the perfect object lesson in how not to end a long-form story, and is a good blueprint to explain how to come to a satisfying conclusion. Just in case you’ve been living in a cave for the last ten years — and incidentally, welcome back, and tacos are now served in giant Doritos — Dexter is about a serial killer who exclusively hunts other serial killers. This choice of victim comes from Dexter’s cop father, who, in an effort to control Dexter’s murderous impulses, trained him with a code of conduct. Dexter now works for Miami Metro Homicide as a blood spatter expert, alongside his detective sister, and a group of misfits and oddballs. The show ended up with Dexter faking his own death, abandoning his son to be raised by another (admittedly reformed) serial killer, and turning into a lumberjack.

Don’t worry. If that made no fucking sense to you, it made even less sense to those who were watching. That brings me to the first point on picking an ending:

THE CONTRACT. When the series opens, Dexter is a criminal working for the police. There is an assumption that this will eventually cause some form of tension, since, you know, serial murder is still illegal in the state of Florida. In its best years, Dexter derived some tension from the protagonist staying ahead of the law, though as the series marched on, it became less and less plausible that he would not live under a constant cloud of suspicion. Anyone who suspected Dexter of being a killer always vanished without a trace or turned up dead. A number of people in Dexter’s life were murdered by serial killers, sometimes in Dexter’s home. It got to the point where, to explain the worst cops in history, I had to assume Miami Metro had a slow gas leak. In the first episode, the series entered into an unwritten contract with the viewer by the premise alone: at some point, Dexter will have to face the music of his professional life colliding with his extracurricular activities.

THE PEBBLES. A good series will either consciously foreshadow or effectively mine past hints and plot threads for the eventual conclusion. In The Shield, a show that boasts the greatest series finale in history, the end was directly informed by things that happened in the fucking pilot. Dexter was trapped by its own success. The network wanted to have it go on forever, and thus the pebbles that should have started the avalanche of the ending never fell.

THE ARC. As the skill of writing has become both more visible and more documented, talking about “character arcs” no longer sounds like yoga. The beginning tells us who this character is, and the series is his journey to being something else, or being destroyed in the most interesting way possible. The show introduced us to an anti-hero, and the tradition of shows about anti-heroes is that they suffer and/or die for the ways in which they flouted the social order. The show never committed to the idea of Dexter as an anti-hero (and the subtext of the show, confirmed in numerous interviews, was that he was just a straight hero with none of that “anti” stuff), and thus the punishment seemed arbitrary. There was no scene that hinted at Dexter’s love of, or hostility toward, trees. In fact, Dexter as a character was maddeningly static, shackled both by the network and a group of writers unwilling to find anything wrong with his behavior.

THE FATE. When defending their universally reviled end, the writers explained that Showtime, in its finite wisdom, would not allow them to kill Dexter, and thus lumberjacking was the only other possible fate. This level of myopia is instructive, because it shows how we can get stuck into either/or situations. Death or Lumberjack, said the writers of Dexter. Showtime nixed Death, therefore Lumberjack. There was never any consideration for the final story promised in the Contract, and finding an ending that grew organically from that, plus the Pebbles that never fell, or the Arc that was never traversed. They never took a step back and looked at the story they had been telling over seven years to find an honest conclusion.

There are plenty of places online to find fan-written endings to Dexter, and the remarkable thing is how no two are alike. Most have the same elements, namely that the final season should have revolved around Miami Metro Homicide closing in on our titular serial killer, who finds himself tested by the lessons in humanity he has learned over seven seasons, ultimately resulting in either his death, fundamental change, or you know, cutting down trees and eating his lunch. They are all different, but yet every single one is preferable to what we got, leading to the final, and most important element of writing a proper ending.

THE EDITORIAL OVERSIGHT. Show your ending to a couple people who you are not paying. Listen to them. If they all say the same thing, change the goddamn thing.

Filed under: I'm Just Sayin, Level Up, Moment of Excellence Tagged: Death or Lumberjack, Dexter, endings, Rules of Writing

October 18, 2013

Dookie?

Kiss him! Kiss him!

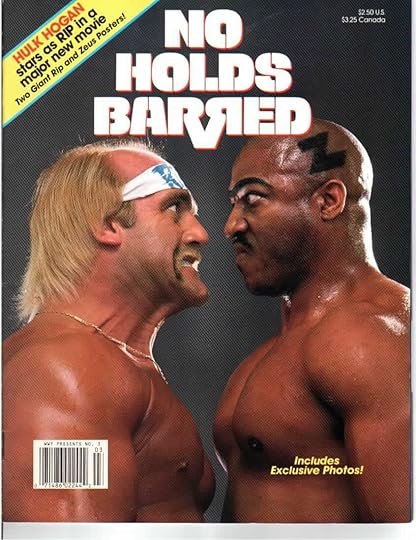

The all-consuming pop culture obsessions of one year are the embarrassing relics of the next. Try showing Gangnam Style to someone who managed to miss its ubiquity, and you’re likely to get a blank stare and a pair of safety scissors through the eyeball. Mostly because the only people who missed that video are in mental hospitals for the criminally insane. Professional wrestling has enjoyed several periods of Gangnam Style-level pervasiveness, rising and falling like the tides, or like King Ghidrah trying to get out of bed in the morning. In the ‘80s, Hulk Hogan was the pre-eminent good guy (or “Babyface” in wrestling’s bizarrely creepy vernacular), and in 1989, he made a movie called No Holds Barred to take advantage. I’d say it hasn’t aged well, but that’s like getting mad at Judi Dench for not celebrating her 83rd birthday by turning into Alison Brie.

Tagline: No Ring. No Ref. No Rules.

More Accurate Tagline: No Shirt. No Shoes. No Homo.

Guilty Party: Hulk Hogan (Terry Bollea) and Vince McMahon wanted to cash in on the WWF’s and Hogan’s (at that time waning) popularity with a movie. Unsatisfied with the script they were given, they supposedly stayed up for 72 hours rewriting it, because McMahon can’t do anything that won’t get him hospitalized. What we’re left with is a conception of professional wrestling that could only come from a seven-year-old who has over two decades of experience on the inside of the industry, which is only one way this film treats the space/time continuum like a lotion-filled tube sock. We somehow wind up with a movie in which pro wrestling is entirely real, yet the entire plot hinges on corporate meddling and grubbing for ratings. You know, what every kid loves about wrestling.

Synopsis: Rip (Hogan) is the most popular wrestler in the WWF, despite a weird biker mustache, no discernible ring skills, and a combination of stringy hair and male pattern baldness. In this, the film is documentary-level accurate. It opens with him dispatching a challenger with such distressing ease, the announcers wonder if anyone can challenge him. This isn’t important, but the challenger’s name is Jake Bullet. Due to announcer Jesse Ventura’s carnival-barker-meets-drill-sergeant cadence, it really sounded like he was saying Jim J. Bullock, leading me to the brief hope that Hulk would be fighting Monroe from Too Close for Comfort.

This is him after he was gang raped in a very special episode. No, really. The ‘80s were seriously fucked up.

Sleazy executive Brell (Kurt Fuller) of the World Television Network, is desperate to sign Rip. Knowing Rip’s word is ironclad, Brell, nonetheless summons Rip to a meeting and hands him a blank check. Rip refuses by shoving the check down Brell’s throat and walking out (and giving his weird hang loose gesture to the camera because this is The Office now, I guess).

Rip gets a new account executive, Samantha Moore (Late ‘80s/Early ‘90s sex symbol Joan Severance) and they begin a deeply uncomfortable flirtation that reveals Rip to be a French-speaking erudite man of the people who loves to do middle-of-the-night calisthenics in an upsetting pair of hot pink bikini briefs.

His plan to hire Rip away thwarted, Brell somehow finds an underground club where men fight without the benefit of a referee or a full set of teeth. He decides he will televise this with the catchy name of “The Battle of the Tough Guys,” and recruits a vibrant cross section of hillbillies, hicks, and rednecks to do battle on TV. Into this kumite steps man-mountain Zeus (Tiny Lister), who wins the competition, and immediately becomes the face of the enterprise. He turns out to have a pretty extensive criminal record, which is mentioned by Rip’s trainer, who suddenly enters the narrative like a wise old ninja.

Zeus challenges Rip to a fight at a small charity event, because apparently a press conference would make no sense. Rip refuses, but reconsiders when Zeus badly beats Rip’s brother Randy (Mark Pellegrino, you remember him as Jacob from Lost). Rip awakens Randy from his coma with the power of love.

At the final televised battle, Brell kidnaps Samantha to force Rip to take a dive, but Sam escapes. Rip beats the tar out of Zeus, and scares Brell into backing up into some live wires, which electrocute him to death. Rip flashes a hang loose at the camera, and freeze frame.

Life-Changing Subtext: Murder is fine as long as you don’t break your word.

Defining Quote: The best quote in the film will have to be saved for the Transcendent Moment, but fortunately, Kurt Fuller’s Brell has maybe the strangest verbal tic I’ve seen in a long time. He calls Rip “jockass” at several points, clearly under the impression that that’s a thing and not something his cellmate brought up to make the experience seem more normal. Brell yells it so much it’s like his catchphrase, boldly bucking the trend of a catchphrase being catchy or a phrase.

Standout Performance: Tiny Lister really brings something special to the role of Zeus, a unibrowed monster who communicates entirely in whispers and animal screams, and who has the flexibility of a dead man in a full-body cast. His fighting style is a combination of yelling and double-handed chops. He makes Tor Johnson look like Jet Li.

What’s Wrong: It was written by two steroid monsters in the middle of a 72 hour writing binge. This movie has so much bull semen in it, it gives McDonald’s employees PTSD.

Flash of Competence: Kurt Fuller and David Paymer are both reliably good actors, and Joan Severance is pretty far from terrible.

Best Scenes: Rip and Sam have to embark on a romance, because Hulk Hogan and Vince McMahon hate us. So when the two inevitable lovebirds are shacked up in a hotel together, sparks will fly. As Sam comes out of the bathroom in her 1989 high-waisted sleep lingerie, she finds Rip bent over in booty shorts. And these shorts would be considered daring for a German tourist. I think I gave Hulk Hogan an impromptu colonoscopy totally by accident. Later on in the same scene, apparently convinced he still had a shred of dignity that could be found with the more powerful electron microscopes, Rip strips off the booty shorts for a pair of pink bikini briefs.

The training montage is hilarious, somehow upping the ante from Rocky IV, which I thought had topped out on any scale it had attempted. While Zeus trains for the fight by breaking concrete blocks with his hands, Rip trains by teaching his brother to walk again. Sadly, this did not set up a finishing move in which Rip tenderly helps Zeus totter along a pair of parallel bars.

Rip dispatches his trainer to rescue Sam, and shoots the old guy the most stern, solemn hang loose I’ve ever seen. I had to rewind it three times just to make sure I wasn’t having a stroke.

Transcendent Moment: After Rip shoots down Brell’s attempt to hire him, the limo Rip’s riding in takes him to a warehouse. At this point, Hulk Hogan puts physics in a sleeper hold, and jumps out of the roof of the car. Yep, just jumps right the fuck through the roof. He then beats up all the thugs who were waiting for him using an array of pro wrestling moves ranging from “punches” to “slightly different punches.” And then, something incredible happens.

Rip yanks the door off and grabs the limo driver. He then proceeds to grunt and make a set of faces like he’s trying to shit out a watermelon. And he just… keeps… doing it. I kept waiting for him to break character, look off camera, and shout, “Line!” Or at least get a shot of the goddamn watermelon. As it turns out, he’s not the one with the bowel issue.

No Holds Barred was an attempt to cash in on the popularity and charisma of Hulk Hogan. It’s safe to say the project was doomed from the start.

Filed under: Puffery Tagged: Hulk Hogan, No Holds Barred, pro wrestling, the '80s, Vince McMahon, Yakmala!

October 11, 2013

Liner Notes: City of Devils

I do a lot of conventions, and I learned one thing very quickly. When someone stops by my booth, points at the rack of books, and asks what they’re about, it pays to have what’s called an elevator pitch to spew at them. It’s called that because if you happen to find yourself in an elevator with Harvey Weinstein, or Frank Darabont, or Nicolas Cage, you have the length of an elevator ride to convince them to make your movie. (With Cage, you can just shout “TAX HAVEN!” so maybe he was a bad example.) It’s always one or two sentences that distills your deliriously complex work of unparalleled art into a simple idea that even a film executive can understand. Some spring fully formed to the lips the instant you pitch them. Others are like pulling teeth from an amorous rhino. I think I’m finally homing in on my City of Devils elevator pitch. See what you think, and tell me if I can do better: “It’s about the last human detective in a world of monsters.” I pause. “It’s a comedy.”

I do a lot of conventions, and I learned one thing very quickly. When someone stops by my booth, points at the rack of books, and asks what they’re about, it pays to have what’s called an elevator pitch to spew at them. It’s called that because if you happen to find yourself in an elevator with Harvey Weinstein, or Frank Darabont, or Nicolas Cage, you have the length of an elevator ride to convince them to make your movie. (With Cage, you can just shout “TAX HAVEN!” so maybe he was a bad example.) It’s always one or two sentences that distills your deliriously complex work of unparalleled art into a simple idea that even a film executive can understand. Some spring fully formed to the lips the instant you pitch them. Others are like pulling teeth from an amorous rhino. I think I’m finally homing in on my City of Devils elevator pitch. See what you think, and tell me if I can do better: “It’s about the last human detective in a world of monsters.” I pause. “It’s a comedy.”

Yeah, it could probably use some work, but the preview copies did well at Scare L.A. I’ll probably hit on the perfect one right after convention season ends, because that’s how the human mind works.

I’m not quite certain where the idea for the actual book initially came from. City of Devils is the seventh novel I’ve written, nestled right between Everyman and Coldheart. At the time, I was coming off writing horror, and for those who maybe haven’t checked out my horror, it can get a little dark. I was in the mood to write some comedy, which I hadn’t done since my first Candlemark & Gleam publication Mr Blank. Of everything I wrote, that was the one that flowed most freely, and I was hoping to capture that airy feeling I had when writing it. That it would be a comedy was a given, and ditto for noir, putting me right smack in the middle of my comfort zone. I started thinking about alternate worlds I liked, and many of them came down to the same principle: the last human being in a world full of [blank].

Wrong Blank.

I love monsters, and have since I was very little, probably a gift from my father, who never met a horror move he didn’t like. He was a devoted fan of the classics, and bought me a set of the Universal Monsters action figures which are sadly lost now, victims of my childhood. When they invent time travel, I’m going back to get them. Maybe that’s why they were lost? GODDAMN IT, FUTURE ME. Anyway, other than the action figures, all of which were in steady rotation (it was not unusual to see the Creature from the Black Lagoon cruising around in Luke Skywalker’s landspeeder), I remember quite clearly a Universal Monsters coloring book. My favorite page was The Fly, so much so that in the fifth grade (or thereabouts), I dressed up in a homemade Fly costume for Halloween. We started with one of the cheap Jason hockey masks, cut a couple tennis balls in half for the eyes, added some pipe-cleaner feelers, and spraypainted the whole thing. Along with a three fingered glove, a hood for my head, and a lab coat, I had my favorite costume of my youth. That’s partly why the very first monster you see in the finished novel is the Fly (why he’s named after a Cramps song has more to do with my love of rockabilly, which didn’t start in earnest until much later).

Taking these two ideas, I had the last human being in a world full of monsters. That was an idea with legs (lots and lots of evil spider legs), but I had to work out the metaphysics of the whole thing. Did the monsters show up like immigrants? Were they invaders? What the hell, man? Because many of the classic monsters start as human — vampires, werewolves, mummies, and so on — I took this as the baseline. Monsters turn humans into themselves. That’s how they reproduce. After that eureka moment, the world really fell into place, from the station of humanity, to the Fair Game Law, and finally the (hopefully not obnoxious) metaphors of the whole thing.

With the world in place, I turned to the plot. I made the decision that I wanted to get back into noir. I hadn’t written any since Undead On Arrival, and when I started trying to hammer out the plot, I found, with a mounting sense of horror, that I was out of practice. The connections between plans and thugs and dames that used to be almost instinctual had faded. I realized I would be best served connecting the Evil Plot with the central metaphysics of the world. Doing so would save me time and reader interest, as I wouldn’t need to double up on the exposition. By explaining the one idea, I would prime the reader for the second, and then that first part wouldn’t seem like such a waste of time. Hopefully.

The main monster characters came from a desire to showcase some of my favorites from the classics. I decided early on that there would be no major vampires, simply because of overexposure. The rest were selected mostly for personal preference. I just happen to like phantoms, gremlins, and crawling eyes. From there, I sketched out the prevailing social order and tried to think of logical occupations for each kind of monster. Phantoms had to be musicians. Gremlins were inventors and machinists. Werewolves were cops. It all had to make sense in the internal logic of the world.

“Oculon” was the first name that popped into my head, and one of the primary catalysts for actually sitting down and writing. Rebirth names became an integral part of the universe, and truth be told, one of my favorite parts, since I got to indulge. As an author, I value a sense of audacity. I like it when someone has the stones to do something big and weird. I felt like giving characters names like Oculon, Ugoth the Castrator, or Hexene Candlemas, was the kind of thing that took confidence, something of which I’m often in short supply. Some of the names were flashes of inspiration, springing fully-formed onto the page: Serendipity Sargasso, Lou Garou and Phil Moon, and Cacophony Jones and the Disasters. Others went through a few drafts before I got what I want: Aria Enchantee, Imogen Verity, and Lobo Castle.

I was, of course, haunted by the notion Kate Sullivan, the big boss of Candlemark & Gleam, would hate the book. There’s no greater fear than the possibility of not getting what we really, really want, and this is the phenomenon that describes the life of an author. Well, Kate loved it, but her notes pinpointed a problem that I knew, in the back of my head was going to be there. The timeline: she had no idea when the damn thing was to take place.

I intended it to be in June of 1955 (though I never come right out and say it in the book, mostly because I’m a cryptic bastard), but it’s not our 1955. History diverged ten years earlier when the monsters started appearing, so Los Angeles isn’t going to look exactly like it did then. I used pictures of the city in the late ‘40s as a guideline, and in my mind added scars from the Night War and additions for monsters. Culture would likely still advance, which is why there’s a rock and roll band running around. Well, that and that I love the 1984 cinematic oddity Streets of Fire, and desperately wanted an equivalent of the Bombers in my city. And yes, Cacophony Jones is totally supposed to be Phil Alvin from the Blasters. Except that Phil is by all accounts, a really nice guy and not a criminal biker. Imogen’s house is also very real, and a couple of blocks from where I grew up in the Echo Park area of Los Angeles. You can probably find it on Google Earth without too much trouble. Look for the swan hitching post. The whole neighborhood is a historical zone for all the turn-of-the-century Victorian houses.

The reaction to the book has thus far been almost entirely positive, so I should probably get back to work on the sequel here. Escuerzo is, after all, still missing.

Filed under: Puffery Tagged: Candlemark and Gleam, City of Devils, creature feature, Liner notes, monsters, noir

October 7, 2013

EVERYMAN. 99 cents.

And if that prompts you to buy the book, I have even better news: you can, for less than a buck.

http://www.amazon.com/Everyman-ebook/...

October 4, 2013

UNDEAD ON ARRIVAL. Free.

http://www.amazon.com/Undead-on-Arriv...

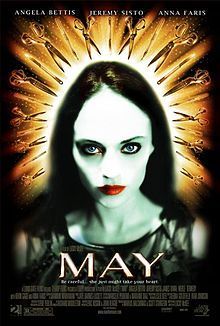

Now Fear This: May

Doesn’t she seem fun and quirky?

There was a time not too long ago where “indie” just meant “independent.” In the movie industry, that meant not backed by one of the big boys like Paramount, Warner Brothers, or 20th Century Fox. Ironically enough — well, not ironically to anyone who actually knows how capitalism works, but whatever — the boom of independent cinema was fueled by the big studios starting “independent labels,” which were essentially sub-studios to acquire, finance, and distribute more risky fare. While Disney couldn’t put its hallowed, family-friendly name on the brilliant, game-changing, and ultraviolent Pulp Fiction, Disney subsidiary Miramax sure could. This was briefly very good for the film industry, as a number of new and daring voices were allowed to be heard, reshaping the cinematic landscape like nothing seen since the mid-‘70s.

I say “briefly” because no incredible proliferation in any forum goes on for long. Look at the Burgess Shale sometime. During the Middle Cambrian period, about 505 million years ago, evolution got into the absinthe. The resulting period of crazy saw the genesis of animals that had never existed before with nothing even vaguely analogous in the later fossil record. Mother Nature basically said “fuck it,” and rolled the dice. And then, just like that, almost all of it died out, preserved only in a few isolated plates of shale for paleontologists to puzzle over and pedantic amateur film critics to reference in needlessly digressive introductions.

“Needlessly digressive and self-indulgent. B minus.” — shrimp butt-mouth monster

Much like the bizarre explosion of life documented in the Burgess Shale, the proliferation of “independent” film meant more and more voices were added to the mix, and these were of varying quality. (I think I sprained something on that segue.) The rules started to calcify as other movies were made that were not as inventive as the earlier ones, and merely aped or expanded upon parts of the first wave. The transformation of “independent film” as the description of a method of distribution into “indie film” as a genre had begun. Indie Films were about twentysomethings navigating the turbulent-yet-spiritually-void world of the late ‘90s and early ‘00s. Frequently self-absorbed, these quirky protagonists met other quirky individuals, fell in and out of love, and drifted through that nebulous existence post-college. Indie films had become as hidebound as any other genre.

Which brings me (finally) to this week’s film, Lucky McKee’s May. Made in 2002, right at the tail end of the indie boom and when total self-absorption was going out of style, it has all the hallmarks of the prototypical indie film. Quirky protagonist May (Angela Bettis) has an unusual job as a veterinary assistant. She falls in love with Adam, a bohemian mechanic with a dark side (indie mainstay Jeremy Sisto). She works with Polly, an oversexed and vapid lesbian (a pre-surgery Anna Faris). She has a brief interlude with gutter-punk Blank (James Duval, most famous as Frank, Donnie Darko’s bunny pal). In a bit of news that might surprise those who remember when this was about horror movies, the bulk of the movie’s running time is devoted to shy May attempting to forge the first real relationships of her life. It would be completely understandable if a viewer forgot the opening shot of the film: May clutching her bloody eye and screaming in agony.

May’s eye is a persistent symbol throughout the film, both as the initial reason for her lonely existence and a signal to the viewer about what sort of person May is. She sees the world differently than most people, and not just because one of her eyes is constantly struggling to look at her nose. May’s mother is one of those emotionally closed-off and appearance-obsessed WASPs that seem to exist only to raise their children to be sociopathic monsters. In a bid to make her daughter normal, she tells May to keep her eye covered with a patch while they try to fix it. Because there’s nothing like an eyepatch to make a kid conspicuous, his turns May into an outcast, which mom further fails to fix by giving her Suzie, a doll mom made. Mom forbids May from ever taking Suzie out of her glass case, setting up the sense that Suzie is the perfect daughter, seen not heard, beautiful in her perfection, while May is the little weirdo mom can’t help but be disappointed in. Not certain that she’s fucked little May up irrevocably, mom tells her daughter, “If you can’t find a friend, make one.”

I’ll play with you foooooreeeeeever

May has taken this to heart to a terrifying degree. She lives alone, unless the army of dolls that are scattered around her apartment like an army of undead babies count. Suzie is kept in a position of honor, and May confides to the inanimate object. In most indie movies, this would be the indicator of a delightful quirk, some sort of manic pixie path to happiness. At any second, she’s going to put on some false eyelashes, the Shins will kick in on the soundtrack, and she’ll be as cheerful as her seasonal name. Yet, even in this section of the film, her pixiness is less Jess Day and more Carrie White. May is a little too weird, a little too damaged, and her attempts to reach out only backfire and drive her deeper into her own little world where her abusive relationship with Suzie continues to fray.

Suzie is inanimate, but she is controlling. She watches May constantly, and apparently influences her to do odd things, such as biting Adam on the lip hard enough to draw blood during a makeout session. The film chronicles Suzie’s path to escape and eventual takeover of May’s psyche, an escape that culminates in a rather unpleasant blood sacrifice. I don’t want to spoil anything, but it involves blind children and is one of the more horrifying things I’ve ever seen.

This is right around where May reveals its endgame. We were not watching an indie film about a pixie finding her wings, we were watching a horror movie about a damaged woman constructing her perfect friend out of the parts of flawed people. The last act of the film plays out in delirious fashion, as May gives herself over entirely to Suzie, and hunts the people who disappointed her one by one. McKee layers on the classic symbolism here: blood in milk showing us the destruction of innocence, the gift of a blind girl providing a name like a prophecy, and of course, that opening shot we have to get back to. The final shot of the film is pure fantasy, though the movie’s adherence to grubby realism grounds it perfectly.

May is a wonderful bait-and-switch in the mold of Audition, though without the infamous torture sequence. It deconstructs the tropes of the indie film, making the point that someone that quirky is likely to be more dangerous than charming.

Filed under: Puffery Tagged: Angela Bettis, friends, indie films, Lucky McKee, making dolls, May, Now Fear This

September 27, 2013

Lifetime Theater: An Amish Murder

As both of my readers are aware, one of the central goals of this blog is extracting meaning from meaningless bits of pop culture, like a mosquito greedily sucking on the desiccated remains of Imhotep. This began with my twenty-six part series on ABC Afterschool Specials and continued through my ten part journey through a collection of very special episodes of Blossom. Well, I’m all out of terrible gag gift DVDs, so I was left to turn to the one place where reliably empty television purports to teach lessons: the Lifetime network. If you’re in the mood to be charitable, you can say that Afterschool Specials were aimed at children, Blossom aimed at teens, and Lifetime movies are for adults, so I’m slowly hobbling through that Shakespeare riddle or something. No, sorry. There’s as much of a guiding hand in this process as there are in any of television’s great mystery shows. I’m basically doing whatever JJ Abrams thought up while on the crapper.

I’m kicking things off with 2013’s An Amish Murder, a title containing two of my favorite nouns. Because of my love of true crime and the Amish people (which probably owes its genesis to Witness, when Han Solo banged Maverick’s girlfriend in order to save the drug lord from Brick, but it’s possible I’m misremembering), I take a special interest in stories about the Amish and crime. I was morbidly fascinated by the gory tale of Edward Gingerich, who murdered his wife in a turn of events that could advertise for the importance of a well-ventilated workspace. I was amused by the Amish beard cutting attacks, mostly because if you need a specific kind of facial hair to get into the afterlife, chances are your religion is ridiculous. So with those cases in mind and a passing familiarity with Amish culture, I dove right in.

The film introduces our heroine the way all assertive-yet-damaged female cops meet their audiences: through jogging. I’m not sure what causes a filmmaker to think “you know what shows toughness? Fleeing.” Anyway, this is Kate Berkholder (Neve Campbell, answering that question no one’s asking, “Hey, whatever happened to Neve Campbell?”), the brand new chief of police of a community that includes both Amish and English (that’s the adorable word the Amish use for people who don’t look like Abe Lincoln). Kate has a unique perspective because she used to be Amish, but some horrible event caused her to leave the community. Or, you know, maybe she heard about Breaking Bad and really wanted to catch up. She’s called over to a crime scene where a dead Amish girl bears all the hallmarks of the awesomely named Slaughterhouse Killer, who has been inactive since right around the time Kate left Amish life for the English.

She believes Slaughterhouse to be an Amish guy named Daniel Lapp, something her brother says is impossible due to Kate’s origin story. See, Lapp raped Kate, and Kate gave him the hard goodbye with a shotgun. Her dad buried him out in the Old Mill (of course there’s an Old Mill, this is one of those stories), and the resulting tension led to Kate’s self-imposed exile. Kate thinks Lapp might be back somehow (and briefly filling me with the hope of Amish Zombies, and before you know it I’m half done with a new screenplay: We Come For Your Brains, English), but nope, he’s so many bones under the ashy dirt of the mill. Meanwhile, Kate perfunctorily romances the profiler sent in, and the two actors have so little chemistry it’s like they were shooting their scenes with CGI doubles. She eventually figures out — about an hour after any reasonably genre-savvy person would — that the killer is the local sheriff’s deputy who grew up in the area, moved away at about the right time, and moved back recently. She should have guessed this, since he’s played by ‘80s mainstay C. Thomas Howell, who has the second-biggest name in the movie, and there’s no way he’s playing some meaningless deputy. He tries to kill Kate, but with the timely assistance of the profiler and some local Amish, C. Thomas Howell is arrested.

As the opening credits played, “Based on the novel Sworn to Silence, by Linda Castillo” popped up onto the screen. This gave the project an entirely unintentional link to the Afterschool Specials, as those were all based on books (mostly by Betsy Byars). I had the same impression I took from those, which was that the book was probably a lot deeper than the film. With several books under my belt by now, I can see the little blemishes where the plot was spackled over, both for content and time. Mrs. Supermarket was interested enough, and she’s reading the book on her kindle and has assured me that it is a lot better than the movie. So there you go. The movie is perfectly serviceable as TV movies go, with a couple bona fide past-their-prime movie stars and a director, Stephen Gyllenhaal, who has been a solid professional for many years and whose balls once contained half of two very good actors.

That’s not to say An Amish Murder is without flaws. Kate comes off as very Mary Sueish when she’s consumed with guilt over killing her rapist. The casting renders the killer very obvious, and Lifetime’s commitment to family drama renders the story of a man who bleeds his victims to death rather bloodless. Still, the Amish parts, particularly the shunning, give it some idiosyncratic texture.

The most important thing about An Amish Murder for my purposes is what it teaches us. Well, the lesson appears to be that you can in fact come home again, even if “home” is a weird cult that has a mad-on for buttons. Kate solves the case and catches her killer, in the process making peace with her brother and the man she was supposed to marry. Good for you Kate. Turns out jogging was the right thing to do.

Or wait. It could be “yogging.” Might be a soft J.

Filed under: Puffery Tagged: Amish, An Amish Murder, english, Lifetime, Lifetime Theater, Linda Castillo, Neve Campbell, Sworn to Silence