Justin Robinson's Blog, page 12

September 10, 2015

Tread Who Perilously Series 2: Episode 8

Erik and Justin tread Who safely with two episodes from the Matt Smith era. First, Justin witnesses the Eleventh Doctor’s first day on the job in “The Eleventh Hour,” then, the Doctor and Amy visit with Vincent Van Gogh in “Vincent and the Doctor.” Both Justin and Erik stumble on the pronunciation of “Van Gogh,” Justin gets distracted by Karen Gillan and Erik tries to explain why he doesn’t hate writer Steven Moffat, despite having a number of criticisms about his work. Justin offers his series finale Capaldi Scale totals and we prepare for a one-week stop at Deep Space Nine.

Erik and Justin tread Who safely with two episodes from the Matt Smith era. First, Justin witnesses the Eleventh Doctor’s first day on the job in “The Eleventh Hour,” then, the Doctor and Amy visit with Vincent Van Gogh in “Vincent and the Doctor.” Both Justin and Erik stumble on the pronunciation of “Van Gogh,” Justin gets distracted by Karen Gillan and Erik tries to explain why he doesn’t hate writer Steven Moffat, despite having a number of criticisms about his work. Justin offers his series finale Capaldi Scale totals and we prepare for a one-week stop at Deep Space Nine.

Click here or subscribe to The Satellite Show on iTunes.

Filed under: Transmissions Tagged: karen gillan, matt smith, steven moffat, tread who perilously

September 4, 2015

Lifetime Theater: A Sister’s Nightmare

While watching a film, reading a book, or even listening to a podcast, two simultaneous stories exist in my head. The first is what I’m perceiving. The second is what I wish would happen. The best feeling in the world is when the first exceeds the quality of the second. The next best is when I think, “you know, in a better movie/book/podcast/interpretive dance X would happen,” and then it totally does. This happened while watching this week’s Lifetime Theater, the imaginatively named A Sister’s Nightmare (not to be confused with Lifetime’s A Daughter’s Nightmare, which IMDB was only too happy to recommend if you liked this one).

That’s not to say it’s a good movie. Oh no. I’ve only watched one Lifetime movie thus far that I’d actually hold up as good. Merely that even after as many of these things as I’ve watched, a Lifetime movie that felt like the product of filling in a Lifetime Madlib somehow had the capacity to… surprise is the wrong word. So is delight. How about please? This movie somehow had the capacity to please me. I realize this makes me sound like a Roman Emperor, loudly commanding Lifetime original programming to fight for my amusement, and I think I’m okay with this.

HAVE THE HALLMARK NETWORK BOILED AS WELL!

The Lifetime Madlib should be fairly obvious to anyone who’s still reading along with these. You start with a middle-aged female protagonist. She has a family, a distant or unhelpful mate, and possibly a job in law enforcement. She also has a (probably teenaged) daughter with whom she has a troubled relationship. Also, this daughter has some kind of medical or mental problem that will somehow figure into the finale.

Getting more specific, a woman on the outside of the nuclear family arrangement, one who is usually younger and more attractive, will threaten the relatively stable family life using vaguely-defined vaginal superpowers. While the initial assumption is that our heroine is overreacting at best and crazy at worst, but by the final act everyone realizes that only her steely determination averted total disaster.

A Sister’s Nightmare attacked the Madlib with gusto. In retrospect, it was part of the director’s deep con, since this was clearly a movie for dedicated Lifetime fans. And yes, I’ve come to accept that I am one of these. Jane Rydert (Kelly Rutherford, who is best known to me as Dixie Cousins from the late, lamented Brisco County, Jr.), is a cop in small town Washington. She’s getting married to Phil (Matthew Settle, who I will always know as badass Ronald Speirs from Band of Brothers), a diffident law student who mostly exists to wear sweaters and speak in low, nonthreatening tones. They’re raising teenaged Emily, Jane’s daughter with her now-deceased first husband, and who suffers from crippling aquaphobia. Which requires at least one actor to say “aquaphobia” without cracking a smile.

The monkeywrench arrives in the form of Jane’s older sister Cassidy (Natasha Henstridge) who has suddenly been released from the mental hospital where she has resided for fifteen years. With nowhere else to go, she moves in with Jane, Phil, and Emily. Jane is petrified of her sister, revealing in stories and fragmentary flashbacks Cassidy’s history with borderline personality disorder. Cassidy instantly shows an unhealthy obsession with Emily, and at the halfway point, the movie spills its (obvious) twist: Cassidy is Emily’s biological mother.

Jane reveals her origin story to Phil while he’s sort of mildly upset about the whole thing. Cassidy was an unfit mother who murdered her husband and nearly drowned Emily in the tub. Jane had to shoot her to save the baby. The story has some holes, but let’s be honest: in a Lifetime movie, I’m not expecting an airtight script. The movie was canny enough to use this knowledge against me.

For one thing, they set up Cassidy’s menace well. Her unexpected release is because of the sudden medical retirement of the head doctor at her hospital. We never actually see what’s happening, but anyone who’s ever seen a movie like this — and not even just a Lifetime version — is already assuming Cassidy is responsible via poison or blunt force trauma. Late in the second act, Cassidy gets it in her head to take Emily up to a lake to get over her fear of water, choosing one that the park guide is careful to point out has some treacherous currents. Then there’s Henstridge herself, playing the role with the reptilian menace that made her “the chick from Species” for so much of the ‘90s. Contrasted with Rutherford’s smooth voice and baby doll features, and we know who the bad guy is.

As the final half-hour unfolded, with an increasingly unhinged and suspended Jane stealing her partner’s gun and car to rescue Emily from a lakeside camping trip, I thought to myself, “You know, in a competent movie, Jane would be the crazy one.”

And what do you know? The story came entirely from Jane. Though we were shown it as flashbacks, which implies impartiality, it was the self-serving story of the real villain. So Jane was the monster who threw Cassidy into a mental hospital for fifteen years and had some kind of arrangement with the head doctor (I guess. It’s never stated.), while she stole Emily and raised her as her own.

This might sound like I’m praising A Sister’s Nightmare as a good movie. I’m not. Don’t make that mistake. It’s better than a lot of Lifetime movies out there, but it depends on a thorough knowledge of the network’s rules. I also ruined the twist, which is the best part about it. If you’re going to watch a Lifetime movie, you can do a lot worse.

So what did we learn? When unjustly committing your sister to a mental hospital, check on the head doctor’s health regularly, and try to come to an arrangement with his successor before the handoff. Alternately, if you’re living with your crazy sister who had you committed to a mental hospital, try not to act so evil. Maybe get some allies before kidnapping your/her daughter.

Filed under: Projected Pixels and Emulsion Tagged: A Sister's Nightmare, Kelly Rutherford, Lifetime Theater, Matthew Settle, Natasha Henstridge, plot twists, Whose nightmare is it

September 3, 2015

Tread Who Perilously Series 2: Episode 7

Erik and Justin’s next stop in their televisual adventures brings them to 1978 and the Fourth Doctor’s first Greek myth-inspired story, “Underworld.” The Doctor and Leela help the Minyans aboard starship R1C find the P7E, missing in space for 100,000 years. It becomes unclear if its the past or the future as riffs on Jason, the Sword of Damocles and other Greek myths chase our heroes around miniature sets. Justin reacts to one of the most budget-compromised episodes yet and Erik (weakly) defends his choice to call this a Minotaur episode. Leela is placed on the companion scale. K9 continues his top ranking, despite slow rolls down corridors in this story. And Justin blames John Nathan-Turner for everything, including Stephen Moffat running the current show.

Erik and Justin’s next stop in their televisual adventures brings them to 1978 and the Fourth Doctor’s first Greek myth-inspired story, “Underworld.” The Doctor and Leela help the Minyans aboard starship R1C find the P7E, missing in space for 100,000 years. It becomes unclear if its the past or the future as riffs on Jason, the Sword of Damocles and other Greek myths chase our heroes around miniature sets. Justin reacts to one of the most budget-compromised episodes yet and Erik (weakly) defends his choice to call this a Minotaur episode. Leela is placed on the companion scale. K9 continues his top ranking, despite slow rolls down corridors in this story. And Justin blames John Nathan-Turner for everything, including Stephen Moffat running the current show.

Click here or subscribe to The Satellite Show on iTunes.

Filed under: Transmissions Tagged: bob baker, dave martin, john nathan-turner, k9, leela, tom baker, tread who perilously

August 28, 2015

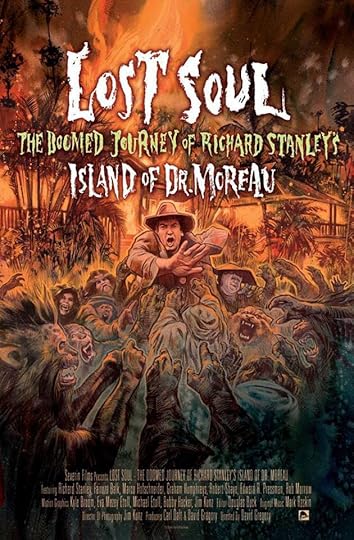

Now Fear This: Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau

They tried to fit a few more words in the title, but ran out of them.

Occasionally I like to use this space to discuss films that are horrifying, but might themselves have a different opinion of what they are. This week’s movie, the incredibly long-titled Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau is not a horror movie on the face of it. It’s a documentary about the making of a horror film, joining Overnight in that rarefied category of making-of documentaries better than their genesis film. Yet, for me, Lost Soul was a horror movie. The most frightening kind, because it was all too real.

I worked for a studio for a little over a year as an in-house writer. I helped adapt a screenplay into a comic, several comics into screenplays, pitched movies for the properties they owned, and swallowed my dignity in daily meetings. Working for a studio is lucrative, but it’s also hell. Executives hold all control, and these are fundamentally businesspeople. They don’t really understand story, and in many cases are actively hostile to any form of creativity. They’re motivated entirely by fear with a little bit of greed thrown in. It’s not entirely their fault, either. Since the business model of Hollywood has shifted, the only way to make money are massive blockbuster tentpoles, and you don’t make Avengers-levels of money by challenging your audience.

In the ‘90s, writer/director/LARPer Richard Stanley was obsessed with making an Island of Dr. Moreau film. Stanley, while being a creative guy, is not the best filmmaker out there. His cult-horror flick Hardware features some impressive worldbuilding in the first half, only to throw it out the window and make Terminator, if Terminator existed entirely on the post-apocalyptic set of Friends. Enough people liked what he was doing, though, to give him a couple more shots at it, and he was going to take it with Moreau.

To his credit, Stanley had a vision. As detailed in fragmentary scenes and lurid pulp drawings, it was a medical dystopian nightmare of a film. Lost Soul lingers over every surviving piece of artwork Stanley had commissioned, showing a surgical gallery populated by feral dog-doctors (dogtors?), a library of squawking skesis-vultures, a pig woman giving birth, and so forth and so on. While watching this, I got swept up in his descriptions of scenes and characters, forgetting that this was the guy who wasted 100 minutes of my life with Hardware, and wishing I could see the Moreau movie as it was in my head.

How do you not want to see that?

I was not the only one. Stanley had the misfortune of selling an executive on his vision, and what always happens, happened. Executives hear tons and tons of pitches. It’s part of the job. So naturally, they gravitate to the odder ones, the ones that break through the constant noise of buddy cop movies, revenge flicks, and superhero origin stories. Like anyone who spends a ton of time in a field of entertainment, it’s the oddballs that attract. Stanley is nothing if not an oddball.

Then, the second phase starts in. You’ve sold one executive, but when the time to make this vision comes around, well, now there’s a price tag. And in a feat of logic so insane it could only exist in great fiction or the real world, selling a star on the project is necessary to get it made, but it also raises the price tag, making it that much harder to get made. Now this ballooning budget film (which had to be ballooned, just to get name recognition) can only be justified if this thing is a blockbuster tentpole. All the weirdness, all the idiosyncracies have to be ironed out. It has to appeal to a broad audience because that’s what the budget demands.

See where this is going? Stanley, drunk on the thrill of having a major studio picture, managed to land some very big stars in Marlon Brando and Val Kilmer, the former of whom is an insane person and the latter such a colossal douche he managed to submarine a promising career in a field consisting almost entirely of douches. Stanley got to watch, in horror, as his project was taken away from him, inch by inch, and moment by moment, until he was unceremoniously shown the door.

This might be the end of another story, but the studio had already thrown too much money into the project. They just wanted to get something out of it. More to the point, the film wasn’t quite done being insane yet. Richard Stanley, while he seems like a nice enough guy, is the kind of crazy you usually meet in gaming stores and used book shops. If he were a little creepier, he might have a collection of Gor novels. This is a man who, in the film’s best sequence, hired the world’s worst warlock named (not making this up) Skip, to help him land Moreau. Skip spent the rest of his life failing harder at doing magic than anyone has ever failed at doing anything. And after Stanley’s firing, he doesn’t actually leave the island, instead turning into Dennis Hopper in Apocalypse Now.

The most dangerous aspect of Lost Soul is that it made me want to watch Moreau again. I kind of remember the movie, one I saw in the theaters with some friends. Even at the time, I knew it was shitty. Yet it retained a spark of delirious insanity from its inception, mostly due to Brando. This is a man dedicated to seeing how much he could get away with on set, and that turned out to be “demanding a personal dwarf.” While it lost the greatness lurking in Stanley’s original vision, Moreau found a more dubious honor: that of a legendary failure.

Lost Soul is fundamentally about the crushing homogenization process of the movies. One that leaves you with one question. Not, “How did they fail with this project?” But the far more damning, “How have they ever succeeded?”

Filed under: Projected Pixels and Emulsion Tagged: documentary, Lost Soul, Marlon Brando, Now Fear This, Skip the Warlock, Studios, The Island of Dr. Moreau, val kilmer

August 27, 2015

My podcast is now on Bleeding Cool!

http://www.bleedingcool.com/2015/08/2...

August 21, 2015

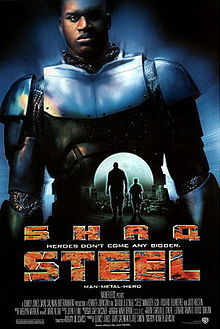

Yakmala: Steel

Shaq was so large, his torso served as low-income housing.

In the late ‘90s, there was no one bigger — literally and the new meaning of the word “literally” — than Shaquille O’Neal. Since he was a genetic freak and good enough basketball player that he stopped hearing the word “no” once he hit fifteen or so, everyone was like, “Sure, Shaq. Let’s get you that terrible movie career you always wanted. How about you cut a godawful rap album while you’re at it?” Thus 1997’s Steel happened.

Tagline: Man. Metal. Hero.

More Accurate Tagline: Man. Basketball. Food. Hammer. Noun.

Guilty Party: Shaq has always been public about his abiding love for Superman. In his days with the Lakers, Staples Center would explode with one of his big plays, while John Williams’s majestic score piped through the house. So it makes a certain amount of sense that Superman’s biggest fan in reality should play Superman’s biggest fan in the comic books: Steel, DC’s answer to Iron Man. Appropriately enough for DC’s more Gee Whiz characters, Steel is noble inventor inspired by the Man of Steel’s heroism to make the world a better place, rather than an out of control drunk with an Ayn Rand fetish. As to why the latter is so much more popular? Well, it comes down to the difference in Robert Downey, Jr. and Shaquille O’Neal. They are acting, and presumably basketball, Bizarros.

Synopsis: John Henry Irons (O’Neal, and yes that’s his name from the comics) is part of some Army division where they make experimental weapons. On a routine test, his reptilian rival Nathaniel Burke (Judd Nelson, doing everything but tasting the air with his tongue), fucks up the test, killing a senator and crippling John’s friend Sparky (Annabeth Gish). Burke gets drummed out of the service, and a disillusioned, and possibly slightly sleepy Irons (it’s tough to tell with Shaq’s acting) leaves the service.

He returns to his hometown of Los Angeles to live with his grandmother, and a character I had no idea was supposed to be his little brother, Martin. Burke comes to LA too for some reason, but he brings his experimental weapons along. Smuggling them in arcade games (because the movie was concerned it might not be quite dated enough), he distributes them maybe? But then there’s an auction in the end where he’s selling them? I don’t know what’s happening. Nothing good.

Anyway, John gets Sparky out of the veteran’s hospital and she and Uncle Joe (Richard Roundtree) help John build a suit of armor and a hammer to fight crime. They even set up a half-assed Batcave under Joe’s junkyard.

Burke kidnaps Sparky and draws the newly christened Steel into a trap. Unfortunately, for him, this only a trap the way locking yourself in a cage with a grizzly bear is technically dating. Steel just goes nuts on Burke (and Burke’s goons have even turned on him because he betrayed them five minutes earlier for no reason). Also, Sparky’s wheelchair is the Death Star.

Irons decides to retire after placing one final prank call to his old boss. The end.

Life-Changing Subtext: Vigilantism is the only way to bounce back after an accident.

Defining Quote: Nathaniel Burke: “Eat the hot dog. Don’t be one.” This is something a Zen monk might say after a massive head injury.

Standout Performance: Hill Harper plays a goon named “Slats” and it’s just… bizarre. He looks like he wandered into the costume trailer, put on everything left over from Streets of Fire and Can’t Stop the Music and emerged and was like, “This is how Hill Harper wishes to be on film.” And no one said shit. In his first scene, he’s wearing black leather hip-waders with some weird halter top, fingerless black leather opera gloves, a vest, and, oh yeah, a fucking eyepatch. He’s the only one in his gang who dresses like this too. I think that’s why he’s in charge. His boys figure if he’ll leave the house looking like that, he’s crazy enough to do anything. I’m beginning to think Harper designed the look for Jared Leto’s Juggaloker.

What’s Wrong: I refuse to call what O’Neal does “acting.” It’s close. He’s trying to mimic the words and feelings of human animals, but as it turns out, being good at acting takes time and practice, which he doesn’t have. Hell, he didn’t even practice basketball, and he was actually good at that. So, instead, you have what I’m going to dub “Shaqting.” While O’Neal is the prime perpetrator of this, you can see other Shaqtors of note with Brett Favre in There’s Something About Mary, whenever Condoleeza Rice was on 30 Rock, and, of course, everything Channing Tatum has been in.

Flash of Competence: The soundtrack instantly throws in a waka-chika, marking this as a blaxploitation superhero movie, and you know what? That’s actually a pretty good idea. Blaxploitation heroes are already pretty pulpy, so it makes a certain amount of sense to add superpowers. Granted, the logical choice is Marvel’s Luke Cage (who basically already is Super Shaft), but if you’re working in the DC stable, Steel is probably the next best thing. Richard Roundtree was brought on to do the handoff, blessing the transfer from 1970s street-level badasses to 1990s cheesy superheroics. He’s great too, but I don’t think Roundtree has it in him to be bad.

Best Scenes: Whenever Shaq gets to act — well, Shaqt — you’re in for a good time. When Burke sabotages the initial test in the beginning (because he’s eeeeeeeeeevil… and kinda dumb), and the wall collapses on Sparky, we get a great “nooooooooo!” moment from Shaq. It’s more of a “SPARKYYYYYYY!” Some prime Shaqting there.

Then when he picks her up from the Veterans’ Hospital. The idea is that she’s feeling sorry for herself because she’s paralyzed from the waist down now. Still, the entire scene is a handicapped woman repeatedly saying “No,” while a (much) larger man ignores her protests, picks her up, and carries her bodily out of the hospital while everyone claps. Now, to be fair, in a normal movie these two would be love interests, but this was 1997 so the idea of a black guy romancing a white woman was still out burning crosses.

Transcendent Moment: Free throws. Christ, the fucking free throws.

This will probably mystify modern audiences who never saw Shaq play, but he was bad at free throws. He was known for it. There were entire strategies based around making him shoot them.

So, because this movie desperately wants to avoid the timeless quality that afflicts your better superhero movies, they introduce a running gag of Steel missing free throws. Yeah, they actually come up with three excuses to have him shoot a free throw. It’s riveting. The final one of these is when Burke drops a grenade into a room where Steel is with Martin, and Steel has to throw the grenade back out through a small hole in the roof. And yes, this means that Steel’s entire character arc revolves around something the actor could not do.

Here’s the thing though. This grenade has the longest fuse in the history of explosives. Steel has time to think about it, pick it up, protest he can’t do it, then accept coaching from his little brother on proper shooting form. This thing took so long, I could have used a flashback partway through to remind me it was a live grenade. Maybe we could have seen what the grenade was like before it got to the island and met the Others. Or why the grenade got sent to prison and how its past informs its romance with Piper.

So about 45 minutes later, Shaq free throws the grenade away, and it explodes. And I’m left with a deep, empty feeling. I got attached to that grenade.

I named him Mr. Splodey.

It’s hard to imagine a time before the superhero dominance of the box office. With flicks like Steel, it’s even harder to imagine it happening.

Filed under: Projected Pixels and Emulsion, Yakmala! Tagged: DC Comics, iron man, man of steel, Richard Roundtree, Shaq, Shaquille O'Neal, steel, Yakmala!

August 20, 2015

Tread Who Perilously Series 2: Episode 5

Erik and Justin’s journey through time and space bring them to 1968 and the world of the Gonds, conquered by the crystalline Krotons. Erik finally introduces his favorite Doctor to Justin while Justin finds himself quite appreciative of Zoe and Jaime bumbles about with a crowbar. The Gond revolution doesn’t go so well and the Krotons wear metal skirts. Wavering 1960s BBC production values are discussed and the Doctor Batmans out of the situation. This episode is dedicated to Wendy Padbury.

Erik and Justin’s journey through time and space bring them to 1968 and the world of the Gonds, conquered by the crystalline Krotons. Erik finally introduces his favorite Doctor to Justin while Justin finds himself quite appreciative of Zoe and Jaime bumbles about with a crowbar. The Gond revolution doesn’t go so well and the Krotons wear metal skirts. Wavering 1960s BBC production values are discussed and the Doctor Batmans out of the situation. This episode is dedicated to Wendy Padbury.

Click here or subscribe to The Satellite Show on iTunes.

Filed under: Transmissions Tagged: fraser hines, jamie maccrimmon, patrick troughton, robert holmes, the krotons, tread who perilously, wendy padbury, zoe

August 14, 2015

Lifetime Theater: Gone Missing

The Lifetime network is just fucking with me at this point.

It’s inevitable that, in a project as long as this one, some themes are going to start to emerge. None were more striking than my discovery of the Alcoholic Mom Trilogy nestled in the middle of some otherwise unconnected Afterschool Specials. Perhaps, though, the discovery of these themes is what this whole endeavor is about. Otherwise, it turns into some kind of weird James Franco-esque pop-culture experiment that makes everyone hate me.

Like that time he instituted a fascist government in Spain.

I just wish Gone Missing weren’t so goddamn boring. Nothing against her, but I’m beginning to think that Daphne Zuniga’s presence in a Lifetime movie heralds a deeply unpleasant 84 minutes. It has nothing to do with her performance, which is perfectly fine for what we’re looking at, but maybe her agent only gives her the scripts the rest of the cast of Melrose Place has already passed on.

To properly explain the plot of this one, I need you to imagine a road. It’s right around San Diego, so over your right shoulder, you see the blue Pacific. Over your left, some dun colored hills with big patches of prickly pear cactus. It’s absolutely beautiful, the kind of place where you want to eat Mexican food, drink bear, and listen to the waves wash up on the sand. But every ten minutes on the road, there’s a turnoff. A really obviously evil turn off. The first one leads to a bear with a chainsaw for an erection. The second one to a vampire’s castle where they make rohypnol. The third one leads to a pack of bikers led by Satan and Dick Cheney. And so forth and so on.

This road you imagined is the one traveled by Kaitlin, an eighteen-year-old high schooler on Spring Break, on a harrowing journey from a border town to her resort hotel in Coronado. She follows that pretty road, dodging past the bear with the chainsaw dick, past the creepily leering vampire in his castle, past Dick Cheney shooting Satan in the face, only to turn off at the last possible one, which is also arguably the only one you might not mind so much. Instead of getting raped, murdered, raped and murdered, put in a snuff film, shipped off to a Macau sex dungeon, or any number of a thousand fates, she suffers a badly broken ankle, a little exposure, and maybe some mild dehydration.

As you might have guessed from that road description, Gone Missing flirts with darkness. Hell, Gone Missing tells darkness how drunk it is, flipping its hair and suggestively waggling its eyebrows. Gone Missing gives darkness a lapdance and invites it home, but at the last minute remembers it has to get up early the next morning and slams the door in darkness’s face. Poor darkness, doomed to go home alone and jerk off to one of those ASPCA commercials with the Sarah MacLachlan song.

So, Kaitlin and her best friend Matty get to go on Spring Break! Yay! But their moms and Katlin’s little brother are coming along. Boo! Moms Rene and Lisa are BFFs from the dawn of time, who are implied to have had a wild youth. Rene has turned into a helicopter mom, complete with loudspeaker and spotlight, so intent on controlling her daughter’s life with the zeal Kim Jong-Un. Lisa is one of those moms who wants to be her daughter’s best friend, and Matty is a burgeoning trainwreck, blind drunk in her first scene and hungover in her second (something Lisa is entirely aware of and dismisses with a breezy sigh). The girls want to have fun with alcohol and condoms and whatnot, but Rene will not stand for such malarkey.

She’s also not a fan of nonsense, shenanigans, horseplay, frolics, fooling around, funny business, hanky panky, hijinks, or bullshit.

After one night, Kaitlin and Matty vanish. The moms experience growing panic as it turns out these two are definitely gone, rather than just avoiding them. In the fine tradition of Lifetime Moms, the two become amateur sleuths. Sure, they enlist both the law and resort security, but the plot is always being driven by these two. Each commercial break leads them to another step along the long and bizarre night the two girls had. Each time they get right next to some horrible fate (Kaitlin nearly gets raped three times. Seriously.), only to stay on the clear and straight road. Even Matty, who goes across the border with three guys and winds up in some terrifying snuff-house, escapes relatively unharmed.

See, it’s Lifetime, not a movie where you need Liam Neeson to find them. This is fundamentally my problem with the movie. Well, that, and the endless scenes of Daphne Zuniga and Lauren Bowles (playing Lisa, perhaps most famous from her turn on True Blood) wandering around a resort and looking frustrated.

The bulk of the drama, other than Kaitlin’s night (played as a series of jittery-cam flashbacks) is the tension between the friends. Basically, the movie wants the moms watching to know that neither Rene nor Lisa’s parenting strategy is right. They’re both just terrible moms. It’s heavily implied that if Kaitlin weren’t smothered and Matty were given maybe one boundary, none of this would have happened.

The most Lifetime-y flourish, of course, is the husbands. Lisa is divorced after her husband cheated on her. For about half the movie, I was convinced Rene was divorced as well, albeit amicably as she and husband Jack talk on the phone. Nope, he just travels a lot for business. Lisa states several times Rene’s marriage is on the rocks, but it never actually goes anywhere. Jack attempts to fly out to San Diego to help with the search and lend support, but never makes it. Rene finds Kaitlin more or less all by herself, just by being more persistent than anyone else. She’s a hard-boiled mom.

Well, that plus her visions.

Yeah, this movie has more dropped threads than a… coat… dropping… factory? Sorry. I didn’t think that one through. Rene has visions of her daughter drowning. They’re so important to the movie that’s the opening shot. I think it’s supposed to either be a red herring for the final fakeout scare (Kaitlin does not take the turnoff into the ocean for a midnight swim), or a weird psychic impulse that leads her to the stretch of shore where she does finally find the weak and injured Kaitlin.

I mean, who cares? I’ve defended a lot of Lifetime movies, both for those offering unintentional entertainment, intentional entertainment, and some unholy middle ground. Gone Missing gives us none of the above. I’m pretty sure it was shot like an Adam Sandler movie: an excuse to get to a San Diego resort for a couple days and maybe shoot a movie.

So what did we learn? Don’t be a helicopter mom, and don’t be best friend mom. Also, don’t be dad.

Filed under: Projected Pixels and Emulsion Tagged: best friend mom, Daphne Zuniga, helicopter mom, Lauren Bowles, Lifetime Theater, possible snuff film, Tijuana adventures

August 13, 2015

Tread Who Perilously Series 2: Episode 4

Erik and Justin’s travels through space and time bring them back to the 1980s and Justin’s least favorite period: the John Nathan-Turner era. This week’s tale, “Time and the Rani” sees the Doctor regenerate into one of the Istari, a rival Time Lord immediately cosplay as the Doctor’s companion and chicken lizard people running with the arm precariously behind their backs. Justin ranks Sylvester McCoy on the Capaldi Scale, Erik reveals he finds Bonnie Langford appealing and both discuss the problem of useless companions. Justin still can’t recall Martha Jones by name.

Erik and Justin’s travels through space and time bring them back to the 1980s and Justin’s least favorite period: the John Nathan-Turner era. This week’s tale, “Time and the Rani” sees the Doctor regenerate into one of the Istari, a rival Time Lord immediately cosplay as the Doctor’s companion and chicken lizard people running with the arm precariously behind their backs. Justin ranks Sylvester McCoy on the Capaldi Scale, Erik reveals he finds Bonnie Langford appealing and both discuss the problem of useless companions. Justin still can’t recall Martha Jones by name.

Click here or subscribe to The Satellite Show on iTunes.

Filed under: Transmissions Tagged: bonnie langford, colin baker, doctor in distress, john nathan-turner, melanie bush, sylvester mccoy, tread who perilously

August 7, 2015

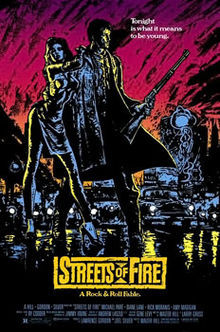

Now Fear This: Streets of Fire

The poster is so ‘80s it can cause spontaneous mullet growth.

As Adam Sandler and Ernest Cline have proven, empty fetishization of ‘80s pop culture is big business. In the rush to embrace this largely imaginary, big-haired, neon-soaked, synth-popped, and pixellated ideal, what tends to be forgotten is one of the defining features of the decade: the ‘80s were fucking weird. That’s one of the reasons the pop culture is as lionized as it is (the other being that those of us who came of age then are getting more of a national audience for our confused rambling). This was in the era of the blockbuster, but before the concept of the blockbuster had become the de facto business model for all of Hollywood.

Since Star Wars invented the concept of money, the bean-counters running the show came to one inescapable conclusion: SF-fantasy was big, and only God and Mammon know why. So men (and it was about 99.99% men, because some shit has not changed) like John Carpenter, James Cameron, Ridley Scott, Richard Donner, Joe Dante, and Walter Hill got to make whatever whale-singing unicorns pranced through the rainbow fairy gardens of their dreams.

Walter Hill has always been fascinated with a grimy, near-noir aesthetic that led him to direct iconic action classics like The Warriors and 48 Hrs, and help write top five horror masterpiece Alien and its top five action masterpiece follow-up Aliens. When Hill built up enough cache to make whatever he wanted, it was not surprising that he chose to set it in a gritty urban dystopia simply labeled (in one of the best opening titles of all time), “Another Time, Another Place…” What was surprising was that it was a musical.

Well, not precisely a musical. Streets of Fire is billed (in its first opening title, because why not, have two, it’s the ‘80s) as “A Rock & Roll Fable.” The movie is bookended with bravura concert performances by fictional band Ellen Aim and the Attackers, and features two full songs right in the middle of what should be the second big action sequences by American Music pioneers and all around badasses The Blasters. There’s a few other songs in there, and each one is more or less at home in the setting, usually illuminating a theme going on. For example, “One Bad Stud” plays right before the first confrontation between hero and villain, while “I Can Dream About You” plays over the final farewell between hero and damsel. There’s no scene where everyone stops dead for a giant song and dance routine and a singalong about what’s really going on in hero Tom Cody’s (Michael Paré, in the film’s largest misstep) unexpressive head.

Streets of Fire is ostensibly an action movie, and in some ways a purer expression of the urban decay on display in The Warriors. While that movie was explicitly set in New York, albeit implied to be a New York of the near future, Streets of Fire is set in a nameless city that seems to go on forever. Seriously, it’s stated several times that it takes the characters hours to go from one end to the other, and the journey from industrial hellhole The Battery to slightly-less-hellish-residential district The Richmond that comprises the second act, takes a full night.

That first concert performance gets interrupted when villain Raven Shaddock (Willem Dafoe being even more awesome than usual) abducts singer Ellen Aim (Diane Lane). In the first great shot of the film (there are several), while the crowd is going berserk over the Attackers’ rollicking ode to the lives of everyone present “Nowhere Fast,” Raven and his leather-clad motorcycle enthusiasts The Bombers stride into the concert hall. Alone among the bobbing and clapping crowd the silhouettes of the Bombers, with Dafoe’s brutal pompadour in the lead, are nearly motionless, like predators in the middle of the herd.

Richmond resident Reva sends a telegram to her badass brother Tom to come home and rescue Ellen, who also happens to be his old flame. Tom, teaming up with Ellen’s manager/current boyfriend Billy Fish (Rick Moranis), and tough wheelman McCoy (Amy Madigan) head into the Battery to get Ellen back, then trek all the way back across the endless city, only to deal with a now revenge-obsessed Raven.

This movie has been a vital part of my aesthetic since I saw it — something that happened so long ago, I have no memory of it. I only know that I was convinced Tom’s guns shot fire for a long period of time because everything he shot exploded into bright balls of orange fire, like his bullets are Michael Bay movies. While I certainly did not understand the sometimes uncomfortable line the film walks between parody, homage, action, and musical, the iconic characters and the episodic plot were ideal for those early days of cable when catching a movie from the beginning was about as likely as seeing the Loch Ness Monster in your bathtub.

Streets of Fire still has an outsized influence on me. The phantoms in City of Devils owe their existence largely to this one. The Howlers were a version of the Bombers, and the Disasters was as close as I could get to the Blasters. Cacophony Jones had Dafoe’s pompadour, but his rock star grimace was inspired by Phil Alvin’s. Hell, one of the Disasters is even named Raven. The climactic sledgehammer fight — yeah, there’s a climactic sledgehammer fight in this thing, and if that’s not a reason to see it, we have no reason to speak — was the impetus for the similar guitar fight in my book.

It’s not hard to see why Dafoe especially had such an effect on me. He is bizarrely hypnotic, from his exsanguinated skintone to his penchant for wandering around in hip-waders, to the sickly Kubrick grin he gives when summoning his gang. It’s, quite simply, the perfect role for a great actor, and not a single piece of scenery gets away without Dafoe’s teethmarks deep into them. His sidekick, Greer, is Lee Ving who you know either as Mr. Boddy from Clue or the punk band Fear (or possibly Flashdance, I guess), packs a good bit of menace in his small frame, even when ceding the floor to his boss. He’s also the reason Bill Paxton is the only actor to be killed or assaulted by an alien, a predator, a terminator, and the lead singer of Fear.

Streets of Fire is a weird window into nostalgia. Not just for what it is for someone like me, but a reminder that the ‘80s were all about the ‘50s. The Cold War, family values, big business, these were the focus of men like Reagan, whose entire persona was right out of a children’s show from the ‘50s. Hill concentrates instead on the seething class resentment of those left behind in the boomtime. Perhaps not what would be expected from an almost-musical, but perfectly in keeping with Hill’s oeuvre.

Streets of Fire is not a particularly important film in the scheme of things. It was intended to be the kick-off of a series, implied when Tom and McCoy pile into their stolen car and speed off for more adventures, but it flopped and killed any chance for a sequel. I own an Ellen Aim and the Attackers t-shirt. And, putting aside that this is an awesome name for a band, every time I wear it, someone approaches me to geek out. This has happened at a Tiger Army concert (the Blasters opened for them), an accent acting class for a radio drama, and most recently, at the San Diego zoo (by one of the keepers, no less). So while it might be little more than a blip on the pop culture radar, there are those of us who love this strange little orphan of a movie.

And we’re going nowhere fast.

Filed under: Projected Pixels and Emulsion Tagged: a rock & roll fable, Another time another place, bikers, Bill Paxton, Diane Lane, Michael Pare, Now Fear This, Rick Moranis, Streets of Fire, willem dafoe