Gary Neal Hansen's Blog, page 26

April 8, 2019

Monday Meditation: RCL Year C, Palm Sunday, Luke 19:28-40 (Liturgy of the Palms)

CC by Susan Sermoneta 2.0

CC by Susan Sermoneta 2.0For Palm Sunday the Revised Common Lectionary offers three different Gospel texts for the varying needs of churches.

Luke 19:28-40

First there is the “Palm Sunday” option (Luke 19:28-40) which sticks to the opening scene of Holy Week: Jesus’ “Triumphal Entry” into Jerusalem. That focus is great, I think, since it nudges you to take every event of Holy Week on its own, prayerfully moving through the great events of our salvation.

Second there is the “Passion Sunday” option (Luke 22:14-23:56). That includes the Last Supper, Gethsemane, Jesus’ betrayal, arrest, trial, and crucifixion, death, and burial. It’s a vast amount of text, more suitable for a readers’ theater presentation where simply hearing the story takes the place of a sermon.

Third there is what we might call “Passion Sunday Lite” (Luke 23:1-49). It’s still a long reading, but it sort of cuts to the chase, starting with the trial before Pilate and ending with Jesus’ death.

The “Passion Sunday” options seem to be extremely popular. The argument seems to be that people won’t come to a Maundy Thursday or Good Friday service. Or the church doesn’t even have those services. Either way, if we don’t do the cross on Palm Sunday people won’t ever even notice it. They will jump straight from the Triumphal Entry to Jesus’ glorious resurrection.

The down side of using the “Passion Sunday” texts, however, is that people entirely miss Palm Sunday. And missing Palm Sunday, it seems to me, people never really get a sense of Holy Week as a week. It has a shape, and the Cross is not, actually, the whole enchilada. There are specific events that build toward the Cross, and those events matter, shaping the meaning of the week –and of the Cross.

But in American Protestantism, it is all Cross all the time. (We even let Easter Sunday get swallowed up into Good Friday.)

As always, I’m fighting an uphill battle on this.

I may get around to posts on the Passion Sunday options. But for today, I’m focusing on Palm Sunday. I won’t be preaching this Sunday, but in my own Holy Week I need to start with a good close prayerful look at Palm Sunday.

A Well-Planned Miracle

Jesus clearly knew exactly how he wanted to enter the city: On a colt. He rides a donkey into town in all four Gospel versions of the story — actually on two donkeys in Matthew.

Matthew and John point out that this was intended to show that a prophecy was fulfilled:

Rejoice greatly, O daughter Zion! Shout aloud, O daughter Jerusalem! Lo, your king comes to you; triumphant and victorious is he, humble and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey.” (Zechariah 9:9 NRSV)

Zechariah’s mention here of both “a donkey” and “the foal of a donkey” seems to account for Matthew’s version having the disciples looking for “a donkey tied, and a colt with her.” For all his concern to show the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy, he wasn’t quite up to speed on the parallelism of Hebrew poetry.

But I digress. Luke makes no mention of the prophecy.

I always thought the whole thing looked like a miracle: Jesus used his God-powers

to see where a donkey could be found,

to hear what the owners would say if the disciples tried to abscond with it,

and to know what words would convince them to let the animal go to be part of Jesus’ prophecy-fulfilling tableau.

Then one day I thought “He probably planned it all out ahead of time.”

If he knew exactly how he planned to enter Jerusalem and exactly when he would do it, he probably communicated with some folks in the suburbs who owned the necessary animal.

By the way, Benjamin, Next Sunday afternoon I’m going to need a donkey. Can I borrow yours?

Sure, Jesus, I’ll tie it right here. They won’t even need to come into the village.

Hey, thanks. If your servants are queasy about it, let them know that my friends will say ‘The Lord needs it.’

Cool. It’ll be our code word, just like in a spy movie.

Um… What’s a spy movie?

Maybe what gave me a little moment of revelation was obvious to you already. I don’t know why I thought it was a miracle thing — except that there are so many mysteries and miracles in the Gospels that it is easy to see them even when they are not the point.

Cloak Sunday

Actually, Year C, when Luke’s Gospel is the focus, might be the year to use the Liturgy of the Passion texts instead of the text for the Liturgy of the Palms. Why? Because in Luke there are no palms.

Not one. Not a single frond. It’s all cloaks.

They put some of their cloaks on the donkey and made a carpet of cloaks on the road for the donkey to walk on. They shouted out.

It was royal and it was festive. There just weren’t any palms.

This Sunday instead of waving palms, the kids in the procession should throw down big piles of coats.

The Praise of Stones

The most evocative thing in Luke’s text, though, the thing that becomes the focus in the end, is Jesus’ interaction with some grumpy Pharisees.

They were indignant at what Jesus’ crowd of disciples were doing.

Teacher, order your disciples to stop” (Luke 19:39, NRSV)

they said.

Were they upset that Jesus set up the scene so that he was fulfilling Zechariah’s prophecy? No they complained about the disciples.

Were they upset about the cloaks being laid down like a carpet? Well that was probably a bit scary to them.

Back in 2 Kings 9, when the prophet Elisha sent a young prophet to anoint Jehu king over Israel. He also sent the prophecy that Jehu would defeat Ahab, the current king. Then Jehu told the military leaders:

‘This is just what he said to me: “Thus says the Lord, I anoint you king over Israel.”’ Then hurriedly they all took their cloaks and spread them for him on the bare steps; and they blew the trumpet, and proclaimed, ‘Jehu is king.’” (2 Kings 9:12-13 NRSV)

The military leaders took off their cloaks and laid them down as a royal carpet for Jehu — at the beginning of his journey to overthrow the current regime.

Were they upset about what the people were shouting while, idiosyncratically, not waving any palms whatsoever?

Blessed is the king who comes in the name of the Lord!

Peace in heaven,

and glory in the highest heaven!” (Luke 19:38 NRSV)

The first line of their song was from Psalm 118:26. They were putting into words the same hope expressed by their carpet of cloaks

If the Pharisees were concerned about the Romans squashing any rebellion in the Jewish community, you can see how all of this would worry them.

Jesus set it up to show he was the messianic king of Zechariah’s prophecy. I think the Pharisees were worried that the crowd of people, now a “multitude of the disciples”, were thinking of him as an earthly king.

It was the same fear Pilate had, and which Jesus specifically denied in John 18:36 — but not in Luke (cf. 23:3). In Luke this claim of kingship, and this threat of insurrection, is the substance of the accusation brought against Jesus at trial (cf. Luke 23:2 & 5).

And now?

The idea that Jesus is king is still pretty dicy for us. We like to sing about it, like the crowds on the road to Jerusalem.

But we have a hard time with the implementation.

If “Jesus is king” means he’ll come and deal with our enemies and our problems, well and good.

But if “Jesus is king” means we have to live by the laws and priorities of his kingdom, that’s a tougher go.

And if “Jesus is king” means we have more allegiance to him than to the totems of our culture — our football team (hey, I live in Pittsburgh…), our flag, or the rights named for us in our constitution — well then that gets to be pretty complicated.

Jesus was very willing to accept the people’s praise for him as king that day. He knew that people would soon be far from praise, and take him to his death.

But that day was about the truth of praise. When they said Jesus should stop the disciples from praising him, Jesus said that was impossible. If they stopped the lifeless stones on the ground would sing out in praise.

All creation was waiting for Jesus the king. All creation needs him as king still.

Anyway, before I go on too long, let me just wish you a very happy Cloak Sunday.

++++++++++++

I’d love to send you all my Monday Meditations (as well as my other articles and announcements). Scroll down to the black box with the orange button to subscribe and they’ll arrive in your inbox most Fridays.

The post Monday Meditation: RCL Year C, Palm Sunday, Luke 19:28-40 (Liturgy of the Palms) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

April 4, 2019

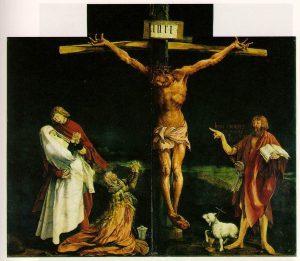

Letters to a Young Pastor: Preaching Good Friday and the Seven “Words” from the Cross

Dear ______:

Dear ______:

Hey, it is GREAT that you got invited to be one of the preachers at your town’s ecumenical Good Friday service. I know it makes you nervous. Nerves are okay — in part it means you take preaching the Word seriously.

Preaching Good Friday

You mention that it makes you more nervous than your previous sermons because you’ve been given very limited time: just 5 minutes. That does make it harder in a way: how will you do what you normally get about 20 minutes for in a quarter of that time?

At one time you signed up for my little online class “Your First Sermon — a Video Course. I would recommend going through the videos and exercises again, knowing in advance what text you’ll be working on and what kind of service it will be part of. There may be questions about the context or purpose of this short meditation that you would want to talk through with your pastor. Or maybe not. That would be up to you — but it is often very helpful.

The kinds of study tasks that I recommend in the video would be just as useful when preaching Good Friday as in a regular sermon. For this kind of service, you might want to spend some time reading all the different sections of the Gospels that will be read and spoken about in the service. That will give you a feeling for all the different moods that are captured in the stories of Good Friday.

Brainstorm other relevant texts

Plus you might want to brainstorm other passages to read that might help fill your mind with relevant biblical context.

For instance, if I was preaching about when Jesus says

Father, into your hands I commend my spirit” (Luke 23:46 NRSV)

I might look back to Luke’s stories where God sent heavenly messages about his Son Jesus.

The “Annunciation” (Luke 1:26-38),

Jesus’ baptism by John (Luke 3:21-22),

and Jesus’ transfiguration (Luke 9:28-36).

Having those stories in the back of my mind when speaking on that passage would give me a sense of Jesus’ intimate connection to his Father throughout his life, and the ways God called out to him — which seems relevant as he calls out and makes his final surrender to return to his Father.

Or if I was preaching on where Jesus says

It is finished” (John 19:30 NRSV)

my first thought would be to take a look at three texts that talk about the “beginning” of important things:

Genesis 1, “In the beginning…” of all creation.

John 1, “In the beginning…” in reference to God the Word, who is God even before creation and is then incarnate as Jesus.

Mark 1, “The beginning of the gospel…” where he jumps straight into the start of Jesus’ ministry.

In some sense, on the cross when Jesus says “It is finished” he’s referring to a journey that relates to these beginnings — something is “finished” here, even though there is a lot more story before “the end” with a new heaven and new earth as at the end of Revelation. But what is “finished” on the cross makes all that new heaven and new earth possible.

Study and meditate till you feel it

The more important thing with this kind of tiny meditation, however, is to spend enough prayerful time with your text so you not only read it but feel it. That way you can spend your five minutes talking about the things that bring a sense of the depth of emotion in Jesus, and the way it impacts us. (If you want a way to get into a text emotionally, see the chapter on Ignatius of Loyola’ “prayer of the senses” in my book Kneeling with Giants.)

Adapt your usual basic sermon plan

With a 5 minute limit, you should aim for maybe one full typed page, double-spaced, to bring to the pulpit. If you read that at a measured pace so everyone can follow along it will be about what you need. (You can find out by setting a five minute timer and reading aloud slowly from your recent sermon to see how far you get. Then you’ll know exactly how much typed material to plan.)

If I were to adapt the sermon plan from my “Your First Sermon” class for a five minute meditation I would suggest something like this:

1/2 page: Retell the story of the text, emphasizing what you think Jesus must have been feeling physically and emotionally.

1/4 page: Talk more about the specific words Jesus spoke and the thoughts that have come up for you about those words through study and meditation.

1/4 page: Leave them with the questions that this text has brought up for you about your own faith and the nature of what Christ and his death mean for you.

In a meditation like this you aren’t trying to give the congregation answers or instructions.

You are thinking and feeling the story along with them — but with a head start.

You just need to lead them through the story and draw their attention to the deep places these events lead us to in our faith and our questions.

Let me know how it goes!

Gary

P.S. If you lost your link to the “Your First Sermon” course, here it is again.

++++++++++++

If you, or someone you know, is nervous about speaking in a Good Friday service, please forward this post to them!

This post contains an affiliate link.

The post Letters to a Young Pastor: Preaching Good Friday and the Seven “Words” from the Cross appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

April 1, 2019

Monday Meditation: RCL Year C, 5th Sunday of Lent, John 12:1-8

James Tissot – The Ointment of the Magdalene

James Tissot – The Ointment of the MagdaleneWhen I saw that the Gospel for the 5th Sunday of Lent in the lectionary’s “Year C” was “the anointing at Bethany,” I expected the text to be Luke 7:36-50. Year C is anchored by the Gospel of Luke. But there it was in the list: John 12:1-8.

I’m not privy to what the committee had in mind when they made their selection of texts but I’m always curious. So I started poking around in the versions of the story in the different Gospels seeing if I could make an educated guess.

It is a very curious subject.

The Anointing at Bethany

Partly it’s interesting because it is a very important story: In both Matthew and Mark Jesus makes a point of saying that the story of the woman anointing him will be told everywhere the Gospel is preached — which seems to be fulfilled, in a way, by the fact that each of the four Gospels tells some version of it.

But what the four stories have in common is kind of minimal.

It happens in Bethany.

Jesus gets anointed.

The person who anoints him is a woman.

That’s about it.

They vary on many details:

In whose house was he anointed?

Matthew and Mark say the home of Simon the leper.

Luke says the home of a Pharisee.

John says the home of his dear friends Mary, Martha, and Lazarus.

Who did the anointing?

Matthew and Mark don’t say.

Luke says she was a “sinner.”

John says it was his dear friend Mary.

How exactly was he anointed?

Matthew and Mark say it was his head.

Luke and John say it was his feet.

Why was he anointed?

Matthew, Mark, and John say she was anointing Jesus in advance for burial.

Luke says the great love she showed in anointing him is connected to the fact that she was forgiven of a great sin.

Most interestingly, when was she anointed?

In Matthew and Mark it happens in the middle of Holy Week — several chapters after Palm Sunday, but before Maundy Thursday.

In John it is just before Palm Sunday.

But in Luke it is actually twelve chapters before Palm Sunday — he won’t even start predicting the passion for two more chapters.

How Many Anointings?

Now if those detailed observations put you to sleep, perk up and try to make this into one event. It’s pretty hard to do:

Maybe he went to the house of Simon the Pharisee, a victim of leprosy and the otherwise unknown brother of Lazarus, Martha, and Mary. Then at some point his good friend Mary (who had always been the black sheep of the family — she’d done some terrible things) broke open a jar of ointment which she’d bought and poured it over Jesus’ head and his feet. She intended to show love, but he interpreted it as anointing for burial.

But even if that works for you, you have to decide whether

Jesus went on from the anointing to his first predictions of the passion,

Or he had already made those predictions and was about to ride into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday,

Or he had already ridden into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday and went on to the Upper Room for Maundy Thursday.

Or maybe he was anointed on three separate occasions?

Lord, every time we go to that town you end up dripping with perfume” — Nathaniel

Hard to say.

But the differences don’t bother me. They are part of the literary artistry of the Evangelists, taking a known and important story about Jesus being anointed by a woman in Bethany, and weaving it into their own Gospel narrative. They may place it where they heard it happened, or where it made a theological and literary point.

John 12:1-8

Anyway, I’m guessing the lectionary committee decided it was more Lenten to use John’s version that took place on the cusp of Palm Sunday rather than Luke’s which came so long before.

They do get Luke’s version into the calendar on occasion: it is used on Proper 6(11) which gets read only if Easter happens pretty early in the year.

For whatever reason, though, what we have right now in Lent of Year C of the Revised Common Lectionary is John’s version.

The Love of Friends

Jesus is at the home of the one family whom the Gospels connect him with as genuine friends. Sure, the twelve were his Apostles, and three among them were his most intimate companions, and one of those three was the one whom Jesus loved.

But he seems to sort of hang with Mary, Martha and Lazarus. Aside from this scene, in Luke 10 he goes there with the Apostles for dinner — you know, the one where Martha served and got grumpy about it, while Mary sat with the other disciples at Jesus’ feet. And in John 11, when Lazarus had died, Jesus stopped by to comfort Lazarus’ sisters and then obligingly raised him from the dead.

There is real affection there.

John 12:1-8 comes only a few verses later. When Mary anoints Jesus it comes across as a gesture of loving gratitude to the point of awe, maybe even worship, for bringing her brother back to life.

And one should note that this is a very different motive than Luke attributes for the anointing. In John, just as in Luke, Mary loves much. But in John there is no hint of penitence or of sin forgiven.

And the Criticism of Friends

The other distinctive feature in John’s account is the treatment of Judas. In Matthew and Mark there is a general conversation complaining that the expensive ointment should have been sold and the money given to the poor. Only in John, Judas alone voices this complaint.

John takes a quick swipe at his fellow disciple, telling us that Judas had been trusted with the whole group’s money, and he used to steal it.

Both the stealing and the tattling are kind of unseemly. But we Christians do bicker against each other, so it adds a bit of realism.

What’s the Takeaway?

I think the sad thing is that our culture has only remembered a portion of the last words that Jesus spoke here:

You always have the poor with you…” (John 12:8 NRSV)

It’s catchy, and it’s true, and it is so easy to make it an excuse.

There have always been poor people. There always will be. And we really do need to be helpful, loving, generous, whether we are giving alms individually or solving the structural problems of society.

The full verse says a tiny bit more:

You always have the poor with you, but you do not always have me.”

Jesus’ point was not that you should never care for the poor.

His point was that generous gifts of love are a beautiful thing.

This is the reasoning that has stood behind centuries of art and architecture given sacrificially to make beautiful houses of worship. Of course those dollars could have been given to the poor. But when given to Jesus, Jesus receives them — or the church receives them in his name.

Mary was extravagant in her love for Jesus. She made a big bold statement pouring out that perfume. Jesus knew he shouldn’t refuse Mary’s gift.

Sure, it seemed impractical. And receiving it was probably extremely awkward.

I mean imagine…

You are visiting friends for a summer barbecue.

Everyone is sitting in the back yard with their shoes off.

Your hostess kneels down in front of you, opens up a bottle of Chanel no. 5, and pours it all over your feet.

Then she picks your feet up and wipes them off with her long hair.

You might not go over to their house any more. I’m just sayin’.

But Jesus receives it. He accepts the awkward love of a friend.

And he puts the best possible spin on it.

On the one hand, the perfume was hers to do with what she wanted.

And on the other hand, with the big picture in mind, Jesus said she was anointing him for burial.

Of course mentioning that at your neighbors’ barbecue would probably be pretty awkward too.

++++++++++++

I’d love to send you my Monday Meditations, along with my other new articles and announcements. Scroll down to the black box with the orange button to subscribe and they’ll come straight to your inbox.

The post Monday Meditation: RCL Year C, 5th Sunday of Lent, John 12:1-8 appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

March 29, 2019

Monday Meditation: RCL Year C, 4th Sunday of Lent, Luke 15:1-3, 11-31

Guercino, Return of the Prodigal Son

Guercino, Return of the Prodigal SonThis Sunday’s Gospel is a very long parable, and one that is much beloved. It has more layers to it than a first reading will find.

Luke 15:1-3, 11-31

The one parable has three main characters. Each character has a lot to teach us. In fact, if you think through the story from each of their perspectives you get three very different, but interrelated Lenten messages:

One is the familiar perspective of the “Prodigal Son.”

Another is the perspective that arises at the end, the “Obedient Brother.”

A third is the perspective on which the whole story hangs, the “Waiting Father.”

The famous German theologian Helmut Thielicke published a book of sermons on the parables half a century ago that took its title from this third point of view, The Waiting Father. He had the wisdom to include two different sermons on this parable. I’ve yet to read them myself, but I think the insight is right: this parable needs more than one treatment.

Jesus’ parables are not tidy, like Aesop’s Fables, each with one simple moral. They are often more confusing the closer you look, not least because like in real life, each person in the tale is living a different story.

The Prodigal Son

First take the familiar character, the Prodigal Son. He’s the younger of two children, unless there were others Jesus didn’t mention.

Something has gone terribly, terribly wrong in this kid’s head. The mistake in his head has led to a problem in his heart – or maybe it was the other way around. Anyway, there is a twist in there somewhere.

He has picked up the idea, rightly enough I suppose, that when his dad dies half the property will be his. But somehow he has failed to notice that while his father is alive the whole estate belongs to dear old dad.

If the boy wants to be rich now, he should maybe get a job and earn some money.

But no. The kid makes his ghastly request:

Father, give me the share of the property that will belong to me.” (Luke 15:12 NRSV)

You know the next bit. He takes the money and runs. Far away from parental purview, he spends it all.

It’s easy for a storyteller to fill in the blanks. I imagine him hosting fancy parties with magnums of champagne, accompanied by dishes of caviar. Since he’s paying, he has lots of new friends even far from home.

But then the money is gone.

No money. No parties. No friends.

Thus a Jewish boy, far from Galilee, can only get a job tending someone’s pigs. This is, of course, a very big bummer.

Depression ensues, followed by hunger, followed by a clear-eyed realization of his error.

He’d probably like to make restitution, start over from scratch, fix things with dad. But he has burned his bridges. With the money flat-out gone, he realizes that what he did was flat-out wrong.

Knowing the error of his ways, he can see his consequences:

He’s damaged his relationship with God.

He’s damaged his relationship with his father.

And those pigs are eating better than he is.

He also sees a possible second-best solution: If he can’t undo what he’s done, maybe he can get his dad to just give him a job. At least his dad’s employees have enough to eat.

So he gets his little speech worked out, and he hits the road. He mutters the speech over and over so he’s ready when he reaches his old homestead:

Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son; treat me like one of your hired hands.” (Luke 15:18 NRSV)

And with that we have a pretty complete Lenten meditation.

We too have been snotty to God, wasted God’s gifts, and ended up in a world of hurt.

We too need to pursue our second-best solution, get our speech in order, and head toward God to ask if we can be his servants.

But that’s not the end of the story.

The Waiting Father

When you look at the father the story goes several levels deeper into gospel territory.

Start with that first scene when the obnoxious younger son basically says

Hey dad! Can’t really wait for you to die. I have things to do. Let me have half your estate now – if you don’t really mind.

The thing is, the father does it.

In the real world nobody is going to recommend this style of parenting. It just can’t be wise to give your kid virtually everything he or she wants.

Everybody knows Herod was daft to say to his daughter that he would give her anything she asked, up to half his kingdom. But he did say it – and it didn’t end well. (Mark 6:17-28)

No, no, of course not. You don’t cash out your IRA and your 401(k) and write a check for half to your son. You set some clear boundaries. You set some reasonable expectations. And you hold on to the PIN to your bank accounts – while, of course, providing generously for your children.

But not the father in this parable. This father just goes for it. Is he a fool? Or is he a particularly wise Parent?

He gives his rotten son everything. Everything he needs, that is, to reach the end of the only rope that will lead to him seeing his own problems clearly.

It is like the dad knew that this kid was an addict who needed to hit bottom. Keeping him in the house was protecting him from himself. Giving him half the estate, while the neighbors gossiped and shook their heads, was the only way.

Somehow this particular dad knew that if he gave the boy everything, he would eventually see himself clearly. He could maybe end up far from the promised land, tending unclean animals like the piggy he had become in his heart.

Maybe that’s why God allows us the freedom to go our own way. We ask for freedom and he gives it, knowing full well we’ll squander it. But if we squander it, maybe we’ll see what fools we’ve been and come back hoping for a fresh start.

It broke the father’s heart to see his son go. You can tell, because the father spent his days on the crest of the hill, looking off in the direction the boy had gone, hoping.

That broken hearted love is the key to the gospel here.

Though when he hit bottom, the son SOUGHT his father,

it was the father who SAW the son — and welcomed him.

The lovely thing is that the father isn’t waiting with his arms crossed and his nose in the air, demanding to hear an apology.

No, this father rushes to his lost son, grabs him in a bear hug, and won’t even let him finish his apology – Check it out. There was one more line in the prepared speech (verse 19) that gets cut off when the son talks to his dad (verse 21).

This father is so overwhelmingly glad that his lost son is back that he gives orders to dress him up and prepare a feast.

…for this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found!” (Luke 15:23 NRSV)

This isn’t primarily a message about parenting — at least not the bit about dividing the inheritance now.

Instead, this is another lovely Lenten message.

When we turn toward God in repentance, we find that he is actually running in our direction,

more aware of us than we are of him,

more eager to welcome us than we are to return.

We think we want to be lowly servants; God welcomes us as lost beloved children.

We think we come in penitence; God invites us to a party in our honor.

But again, that’s not the end of the story.

The Grumpy Older Brother

And then, at the end, we hear a totally new perspective on this story from the grumpy older brother.

In a sense the grumpy older brother’s story is the original reason for the parable. Back at the beginning of the chapter Jesus was confronted by those who disapproved of him hanging out with known sinners. He told this parable as part of his answer to them.

The older brother of the famous prodigal never asked for his half of dad’s wealth.

He never wasted his dad’s resources in a fireworks display of extravagant selfishness.

He was like the scribes and pharisees who objected to Jesus eating with sinners – they spent all their attention on living as God prescribed in the Law, and figured anyone who didn’t was not to be socialized with.

Certainly the grumpy older brother made a reasonable complaint: He behaved well and got no reward, while his dad was extravagant toward a son who had robbed him blind.

But the father’s message to the grumpy older brother is about compassion: Look at the grief of his father which is wiped out by the younger brother’s return.

And from another point of view, despite his complaining, the grumpy older brother really had been rewarded all the while.

He got to eat every day.

He got to have clothes on his back.

He had warm safe place to sleep each night.

And he would still have half the estate at the appropriate time.

The dad wanted him to have all these blessings plus a little perspective.

His little brother had suffered greatly — by his own fault, yes, but he had suffered.

His little brother was among the living, back with those who (at least theoretically) loved him most.

His little brother was a member of the family, and they thought he was dead – but he’s alive.

They thought his little brother was lost forever – but he’s back.

And that’s something to celebrate. If the grumpy older brother can get over himself.

And that’s yet another good Lenten message.

Part of living in repentance is seeing and celebrating others around us. Don’t be a grump, with your arms crossed, nose in the air, ready to condemn someone for their sins. Delight in their growth and repentance. Rejoice in their existence and in the blessings God showers on them — even if you think they are unworthy.

Instead pray the Lenten prayer of St. Ephrem the Syrian:

O Lord and Master of my life, take from me the spirit of sloth, despair, lust of power, and idle talk.

But give rather the spirit of chastity, humility, patience, and love to Thy servant.

Yea, O Lord and King, grant me to see my own transgressions, and not to judge my brother, for blessed art Thou, unto ages of ages. Amen.

++++++++++++

I’d love to send you my Monday Meditations, along with my other new articles and announcements. Scroll down to the black box with the orange button and subscribe to my newsletter, and they’ll zoom to your inbox most Fridays.

This post contains an affiliate link.

The post Monday Meditation: RCL Year C, 4th Sunday of Lent, Luke 15:1-3, 11-31 appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

March 20, 2019

Monday Meditation: RCL Year C, 3rd Sunday of Lent, Luke 13:1-9

Ripped from the Headlines?

Ripped from the Headlines?I think this is a very unusual passage. Luke 13:1-9 is kind of an unvarnished window (now that’s a horrible mixed metaphor) into Jesus’ ordinary interactions.

Why do I think it is “unvarnished”? Well so much of the Gospel narrative is made up of identifiable types of scenes: the healing, the teaching time, the highly symbolic miracle, the conflict with the Pharisees…

But this passage strikes me as unique.

Luke 13:1-9

Luke assumes the scene rather than setting it anew:

At that very time there were some present who told him …” (Luke 13:1 NRSV)

He had spent chapter 12 teaching his disciples and the crowd, with a bit of conversation along the way. Now in 13, “At that time”, a conversation bubbles up, not on the nature of the kingdom or matters of theology, but the news of the day.

…who told him about the Galileans

whose blood Pilate had mingled with their sacrifices.” (Luke 13:1 NRSV)

Some Galileans were murdered at worship – while they were making the required sacrifice apparently.

Strange: It could have been ripped from our own headlines.

Last week 50 Muslims murdered at prayer by a white supremacist in Christchurch New Zealand.

Last October 11 Jews murdered at Sabbath services by a white supremacist in my neighborhood in Pittsburgh Pennsylvania.

Back in 2015, 9 Christians murdered at church during a prayer meeting by a white supremacist in Charleston South Carolina.

Back around A.D. 32, some people from Galilee murdered while making religious sacrifices by Romans.

Alas, Ecclesiastes was right.

So maybe now I have a hint of one reason this little conversation was included in Holy Writ. It needed to be there for just such a time as this.

Luke doesn’t tell us the actual words spoken or identify the speakers. Instead Jesus jumps into the ways people’s thinking goes haywire when they hear about a tragedy like this.

He wants to nip bad theology in the bud. He wants to turn people’s attention to what is theologically and spiritually useful.

1. Jesus objects to blaming the victims

Jesus was quick to make sure they don’t start throwing blame around like internet trolls.

Do you think that because the Galileans suffered in this way they were worse sinners than all other Galileans? No, I tell you; …” (Luke 13:2-3 NRSV)

Why did Jesus assume they were thinking that?

Well, probably because people do so often try to blame someone.

Certainly the perpetrators of all these murders were ready to blame in advance, to claim that their crimes were justified because the people they killed were somehow a problem:

Romans killing Jews at worship had all the self-righteous blame of powerful occupying forces.

And white supremacists deludedly think that somehow African American Christians, elderly Jews, and Muslim refugees are somehow threatening.

Jesus says, and I quote, “No.”

No, do not look for something bad in the people or the culture or the culture or the religion of the victims of violent crime.

No, don’t try, after the fact, to make sense of evil by laying the blame on something you can name in the victims.

And no, don’t let yourself be deluded by evil and go on the attack against those who look different or worship differently from you.

2. Jesus applies the same lesson to natural disasters

Interestingly, although the conversation was about murder at worship, Jesus expands the topic to include natural disasters.

Or those eighteen who were killed when the tower of Siloam fell on them– do you think that they were worse offenders than all the others living in Jerusalem?” (Luke 13:4 NRSV)

Why do you suppose Jesus brought this other tragedy into the conversation?

History would know nothing of the eighteen victims if Jesus hadn’t mentioned them. Maybe the memorial in his words is reason enough.

But I think there’s more.

The original question was about human evil. Don’t blame the victims.

Now Jesus says we ought not blame the victims in cases of natural disaster either.

Were they to blame, Jesus asks?

No, I tell you;…” (Luke 13:5 NRSV)

And why is that important?

Well, look at the news in our day.

Hardly a hurricane or an earthquake comes to destroy a community without some yahoo getting on camera and saying it was God’s judgment on them for tolerating some sin or other that the yahoo particularly dislikes.

Don’t do it. Don’t abide it. Bad things just happen.

Old towers fall down. Sometimes people happen to be standing in the wrong place.

It’s bad enough to die in a hurricane. No need to make it worse by telling the dead it was their fault.

3. Jesus points to what is doable and worth doing

All of that blaming of the victims (whether in advance by perpetrators or after the fact by commentators) gives people something to do while they avoid doing what really needs to be done.

Think of it as Power Procrastination.

But what does need to be done? Jesus is quite clear about it: we need to “repent.”

Regarding the Galileans murdered at worship:

… unless you repent, you will all perish as they did.” (Luke 13:3 NRSV)

Regarding the victims of the collapsing tower:

… unless you repent, you will all perish just as they did.” (Luke 13:5 NRSV)

It gives the passage a rhythm, a structure, an emphasis.

Andrew whispers,

Hey, the Lord’s repeating himself.

John whispers back,

Yeah, he must really mean it.

Then

Come on you goofballs,

Nathaniel whispers, the Apostle in whom there was no guile,

it’s poetry. Can’t you spot a Hebrew parallelism when you hear one?

So yes, Jesus is waxing poetic again, and in good Hebrew style. The repetition strengthens the emphasis.

While you aren’t plotting to harm the people you blame, or blaming the victims of some tragedy, the thing to do is repent — so that, as Jesus said, possibly tongue in cheek, worse doesn’t happen to you.

It’s Lent, which is officially a penitential season. That is, it’s a time to repent.

Repentance isn’t just feeling bad. That’s remorse.

Repentance isn’t even just doing things differently. That, I suppose, is reform.

Repentance, in a literal translation of the usual Greek word for it, is changing your mind .

To repent you have to actually come to a new way of thinking — a way more in tune with God’s way of thinking.

That’s actually very hard, very long term work.

One saying of the Desert Fathers and Mothers which I really love but couldn’t locate in print today, tells the story well:

One very old monk in the desert (Arsenius perhaps, but I can’t be sure) was approaching death. All his brother monks gathered around him, full of admiration of his many years of life as a monk — a life they all admired and looked up to as genuinely holy.

They thought maybe he’d be glad to be going to be with Jesus at last. The dying old man just wept and wept.

Was he in pain? What was the problem, they asked.

It’s because I’ve only begun to repent.”

Jesus wanted the people he was talking with to start that kind of journey of repentance.

He wasn’t asking for a once-for-all decision to be a believer or a follower. He wanted them to dig deep for a lifetime, living in faith and obedience as the Holy Spirit did the work of reforming their whole way of thinking and being.

That’s repentance. It’s still a very good idea.

4. Jesus tells a story to show God’s patience.

And as Jesus points out it still is not too late.

It’s almost too late. But it’s not quite too late.

He tells the lovely story of the landowner who planted a fig tree, and kept coming back year after year to pick some figs.

Nothing. Year after year, nothing.

So he told his gardener to dig it up. Get rid of the useless thing. Start over.

But the gardener loved that tree, figs or no figs.

The gardener lobbied for one more year. Dig up the weeds. Make a trench for the water to go down better. Pile on some good old-fashioned organic fertilizer. Wait and see.

So that’s where Jesus seems to say we stand this Lent.

Let’s face it: we’ve been a bit fruitless.

What kind of fruit is needed?

John the Baptist called it

…fruit worthy of repentance” (Luke 3:8 and Matthew 3:8)

He’s looking for the kind of life that flows from a mind renewed in the pattern of Jesus. Perhaps, as a starting point, a life of loving our neighbors.

But is Jesus serious about cutting down the tree?

Well in both Matthew 21:18-20 and Mark 11:12-21, shortly before the cross, Jesus passed a fig tree and tried to pick a fig.

He found no figs.

He cursed the tree.

It withered.

The scene is weighty with symbolism — and it points back to this very conversation in Luke 13:1-9.

Sounds serious to me.

Time to put some effort into changing my mind. Maybe from now to the end of my days.

++++++++++++

I’d love to send you all my Monday Meditations — as well as all my other new articles and announcements. Just scroll down to the black box with the orange button to subscribe, and they’ll come straight to your inbox.

The post Monday Meditation: RCL Year C, 3rd Sunday of Lent, Luke 13:1-9 appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

March 13, 2019

Monday Meditation: RCL Year C, 2nd Sunday of Lent, Luke 13:31-35

The Gospel text for the 2nd Sunday of Lent (Luke 13:31-35) directs our attention toward Christ’s coming passion – albeit without being anywhere nearly as explicit about the point as he was earlier in Luke’s Gospel. Plus he compares himself to a chicken. Who would want to miss that?

The Gospel text for the 2nd Sunday of Lent (Luke 13:31-35) directs our attention toward Christ’s coming passion – albeit without being anywhere nearly as explicit about the point as he was earlier in Luke’s Gospel. Plus he compares himself to a chicken. Who would want to miss that?

Luke 13:31-35

These lines are easy to gloss past – I’d guess that this, in its entirety, is one of the most forgotten or ignored passages in the Gospels.

But there is good stuff in those passion predictions, oblique as they may be, and also in the earlier details that set the scene.

The Pharisees

Notice, for instance, who it is who comes to give Jesus a timely warning. Herod is out to kill Jesus, and so some kindly friends bring him word and keep him safe. Who were those kindly friends? The Pharisees of course.

The Pharisees get a very bad rap you know. They are easy picking for Christian preachers who want to point their fingers at holier-than-thou legalists who have missed out on the gospel of grace.

This probably tells us more about the preachers and their congregations than about the actual Pharisees.

Jesus tells us something substantive about the Pharisees by his actions and interactions – like in the many texts where they come up without nasty polemical “woes” being thrown down about them.

Jesus is often found hanging out with Pharisees.

Jesus is sometimes found eating in Pharisees’ homes, their guest of honor.

Jesus has any number of interesting conversations with the Pharisees.

Truth be told, Jesus seems to actually like the Pharisees. Maybe that’s a good thing for us Christians, since despite our polemical preaching about the Pharisees, we are often holier-than-thou legalists who miss the boat on the gospel of grace.

So maybe it is no surprise that the Pharisees actually liked Jesus too – enough to warn him that his life was in danger.

The Snarkiness

Second, note well the personality that emerges through Jesus’ words in response to the Pharisees.

Jesus sends a message back to the governor that I find easiest to describe as snarky.

Go and tell that fox… (Luke 13:32 NRSV)

he says.

What? Did gentle Jesus, meek and mild, just send a government official a rude message?

Well, yes, it seems he did. He called Herod a mean name. That’s kind of disrespectful.

On the one hand, this text, along with many others, should retool our inner assumptions of what Jesus is actually like. “Gentle Jesus, meek and mild” doesn’t actually match a great deal of the Gospel evidence.

Jesus’ gentleness is strength used to heal; his meekness is judgment held at bay.

And his mildness is generally lacking entirely.

Passion Prediction 1

Then Jesus gave the substance of his message – two poetic stanzas — to Herod. That led him onto the topic of Jerusalem.

In a way these are all oblique passion predictions.

Or maybe it is better to say that after chapter 9, the coming passion is so much on Jesus’ mind that readers are well advised to keep it in view at all times. It can make sense of what comes out of Jesus’ mouth.

You may remember that chapter 9 was where

the Apostles confessed their faith that Jesus was the Christ, and he began to predict his suffering and death (Luke 9:22),

and at the transfiguration he spoke with Moses and Elijah of his “Exodus” coming in Jerusalem (Luke 9:31),

and he “set his face to go to Jerusalem” (Luke 9:51).

So Jesus’ first two musings about the passion come as poetic stanzas in his message to Herod.

Here’s the first one:

Listen, I am casting out demons and performing cures

today

and tomorrow,

and on the third day

I finish my work.” (Luke 14:32 NRSV)

That’s hardly more than an allusion to the passion, really.

It certainly isn’t a literal time line of the rest of Jesus’ earthly ministry. There is a whole lot of stuff left to happen before we even get to holy week in chapter 19.

But it does point us to the final events of Holy Week when he dies on the Cross the first day, lays in the tomb the second day, and emerges having conquered death “on the third day.”

Passion Allusion 2

The second stanza of Jesus’ little poem on the passion is, if anything, even more oblique:

Yet

today,

and tomorrow,

and the next day

I must be on my way…” (Luke 13:33 NRSV)

What does he mean “I must be on my way”?

I suspect this points back to his conversation with Moses and Elijah about his “exodus” (most English translators read it as “departure”) which is coming in Jerusalem.

He is on his way out of this earthly ministry, this earthly life, through death – but a death that conquers death, culminating in the Resurrection Easter morning.

And it is a journey, a departure, which will be the new Exodus, from slavery to self, passion, and sin into the promised land of new life.

If you think I’m stretching to see this as a passion allusion, note how Jesus ends the sentence:

…because it is impossible for a prophet to be killed outside of Jerusalem.” (Luke 13:33 NRSV)

To me it sounds kind of sarcastic. Jerusalem, the holy city — with such a reputation.

Passion Allusion Three

Which brought Jesus’ mind fully onto the topic of Jerusalem.

You can hardly help noticing the sorrow in his voice as he laments for the city –

the city that kills the prophets” (Luke 13:34 NRSV)

as he calls it.

Sad indeed for God in human flesh to look at a city with a history of killing his personal messengers.

Sadder still for the one who personifies God’s message to anticipate going there, knowing what awaits.

But it is the sadness of God that prevails in Jesus’ words.

How often I have desired to gather your children together

as a hen gathers her brood under her wings,

and you were not willing!” (Luke 13:34)

These particular lines have become quite beloved in recent decades among those who delight to note that Scripture uses non-masculine metaphors and similes for God.

Thus many rejoice that here Jesus portrays his love for the people of Jerusalem using an image that is undeniably female – though it is perhaps less happily an image of a chicken.

But then Jesus seems to indicate that he has given up on them:

See, your house is left to you. And I tell you, you will not see me until the time comes when you say, ‘Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord.’” (Luke 13:35 NRSV)

If you were wondering how this lament over Jerusalem is even obliquely a passion prediction, remember that Jerusalem will indeed hear those words when the children and crowds sing them out, waving palms, as he rides a donkey into town on a carpet of their coats.

++++++++++++

I’d love to send all my Monday Meditations (as well as other new articles and announcement) straight to your inbox. Scroll down to the black box with the orange button to subscribe and I’ll make it happen.

The post Monday Meditation: RCL Year C, 2nd Sunday of Lent, Luke 13:31-35 appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

March 5, 2019

Monday Meditation: RCL Year C, 1st Sunday of Lent, Luke 4:1-13

Duccio, The Temptation on the Mount (public domain)

Duccio, The Temptation on the Mount (public domain)On the first Sunday of Lent we take a step backward in the flow of Luke’s narrative to look at a very lenten issue: temptation. The Gospel text is Luke 4:1-13, the temptation of Jesus in the wilderness.

Luke 4:1-13

Jesus’ three big temptations get all the attention, but a tiny little moment in the ramp-up is worth stopping on. Three observations:

1. Notice what the 40 days were about.

What was Jesus doing for those 40 days?

…for forty days … He ate nothing at all during those days, and when they were over, he was famished.” (Luke 4:2 NRSV)

Jesus spent 40 days fasting. Lent is, historically, a 40 day fasting period for Christians. Coincidence? Absolutely not.

Well, sure, if you are a Protestant Lenten fasting just isn’t emphasized. For Protestants fasting is individual and optional. Many do not fast ever, or when Lent rolls around, we pick something to fast from: TV, chocolate, Facebook — it could be anything.

But if you were, say, Orthodox, it is still emphatically a fasting period. Twenty or so percent of the world’s Christians spend the entire 40 days fasting from meat, dairy, olive oil, and wine.

Basically they become vegan tea-totallers.

It does make the feast of Easter a joyous celebration.

I think we Protestants who strive to be so biblical should at least take note that our Lord himself fasted.

2. Notice when the bulk of the temptations happened.

I don’t think I’m the only one who remembers this story as Jesus going on a 40 day fast which was followed by three big temptations. But look at what Luke tells us:

For forty days he was tempted by the devil. … And when they were over… The devil said to him…” (Luke 4:2-3 NRSV)

This was 40 long days of temptation (while fasting) which were followed by three noteworthy temptations. The temptations during the 40 days ended up on the cutting room floor. These three made it onto the big screen.

Which probably says something about fasting. It isn’t a preventative for temptation. It is a focused time to deal with temptation. And maybe it is a strengthening time to deal with the Big Temptations.

Hmm… maybe we individualistic Protestants could learn something from the shared practice of our Christian relatives in the East.

3. Notice who led him into temptation.

Lastly we should pay close attention to how Jesus got into all these troubling temptations.

Jesus … was led by the Spirit in the wilderness, where for forty days he was tempted by the devil.” (Luke 4:1-2 NRSV)

So God the Holy Spirit led God the Son, Jesus, into temptation.

The point is made even more strongly in Mathew:

Then Jesus was led up by the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil.” (Matthew 4:1 NRSV)

It is an example of what the letter to the Hebrews says:

Although he was a Son, he learned obedience through what he suffered;” (Hebrews 5:8 NRSV)

This helps answer one common question. Whenever I talk to a group about the Lord’s Prayer, someone gets stuck on the line “And lead us not into temptation.” Why, they will ask me, do we need to pray this line when James tells us clearly

No one, when tempted, should say, ‘I am being tempted by God’; for God cannot be tempted by evil and he himself tempts no one.” (James 1:3 NRSV)

Well, the words of James need to be interpreted by Jesus’ own life.

In Luke 4:1-13 God led Jesus into temptation. Therefore we really do need to pray that God would not lead us into temptation. Lord knows we won’t get out of it as deftly as he did.

Jesus’ Big Three Temptations

But what about those three big temptations that came after the 40 days of fasting and temptation? I’ve always figured there was some significance to the three — a pattern to them, something to make them a paradigm of temptation for all of us.

I no longer quite think so. I could be wrong, of course.

But we experience temptation as a pretty individual thing.

Something that you are drawn to with unrelenting longing might just be a big yawn to me.

And the things that I repeatedly fall into, leaving me full of guilt and shame might not every trouble you at all.

It isn’t that our issues aren’t really sin. But we might just not find each other’s issues tempting.

It may be truer that every age has its own set of besetting temptations — not that they capture every sin in a systematic way, but things that the culture generally thinks of as deep and tempting issues.

I’d say in our day it the Big Three might be “sex, money, and power.” And they are especially potent because of the way the each of them is on shifting sand in the thinking of our culture

Things in each category that were thought sinful once are now quite acceptable in the culture.

Things in each category once thought acceptable are now found quite sinful in the culture.

Note, though, how these really don’t overlap much with Jesus’ Big Three temptations. Maybe the power one is there, but sex just doesn’t enter the conversation.

So what is going on beneath the surface of Jesus’ Big Three? A few observations:

Big Temptation 1: Identity

The first temptation goes like this:

If you are the Son of God,

command this stone to become a loaf of bread.” (Luke 4:3 NRSV)

At first glance it’s a temptation about food. But really, food is not a problem. It’s totally okay to eat bread, especially after a 40 day fast.

Even creating bread by miracle is no problem. Read the rest of the Gospel and you see him turn 5 loaves into enough food for 5000 people. Miracle bread is easy peasy.

The temptation is all about identity. “If you are the Son of God” the devil taunts, then prove it.

Well, Jesus really is the Son of God. He could say so to the devil, and he could say so to the world. He had every reason in the world to be perfectly secure in that identity.

But the devil sows a seed of doubt about it.

Prove it. Do something that will convince me of it.

And you know, whatever your identity is, you can never prove it. You can only be it.

If you set about trying to prove who you are — the best pastor, the smartest scholar, the most skilled carpenter — you’re in a world of hurt.

You can never convince a critic. And when you try, you absorb the criticism as self-doubt.

The more you try to prove your identity, the more you doubt it yourself.

Just be.

Big Temptation 2: Allegiance

The second temptation goes like this. The devil, doing something of a miracle of his own, shows Jesus all the kingdoms of the world, their glory, their authority. Then he says,

If you, then, will worship me,

it will all be yours.” (Luke 4:7 NRSV)

At first glance, it’s a temptation about power, or maybe wealth, or authority. That’s what the devil promises to give him.

But the real temptation is all about allegiance. Jesus, and everyone else on earth, is called to worship and serve God alone. The Law of Moses puts that call at the highest level:

You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might.” (Deuteronomy 6:5 NRSV)

“All” brooks no competition. We are to be all for God — every fiber of our being, every ounce of our devotion.

Scripture sometimes puts it in terms of citizenship. Paul tells us our citizenship is in heaven. That’s why Jesus spent so much time talking about the Kingdom of God. That’s our true identity. (See Ephesians 2:19, Philippians 3:20)

We think we are Americans, or Canadians, or whatever, who happen to be Christians.

We are supposed to be Christians, who happen to have been born in America, or Canada, or wherever.

Just like eating bread was not a temptation for Jesus, having all the world under his authority was not a temptation. He himself proclaimed, as he commissions his apostles and ascends to heaven

All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me” (Matthew 28:18 NRSV)

He didn’t get that authority by bowing down to the devil. Jesus is the rightful ruler of heaven and earth.

Giving his heart’s devotion, his service, his allegiance to anyone or anything other than God? That would be a big problem.

Like Jesus, we need to hold fast to our allegiance to God even if it goes contrary to country, or culture, or fashionable trend.

Big Temptation 3: Authority

The third temptation goes like this. The devil does another miracle, swooping Jesus out of the wilderness and over to Jerusalem, up to the top of the temple of God.

If you are the Son of God, throw yourself down from here,

for it is written,

‘He will command his angels concerning you, to protect you,’

and

‘On their hands they will bear you up, so that you will not dash your foot against a stone.’” (Luke 4:9-11 NRSV)

At first glance it looks like we are back to issues of identity. The devil’s line starts that way.

At second glance, though, it looks like it is a temptation about authority. Not authority over nations, like in the second temptation. The issue here is spiritual authority.

In both of the previous temptations, Jesus won out by quoting an authoritative text: the Bible.

Here in the third temptation, the devil quotes the Bible right back at him.

The Bible says you can throw yourself down from here. So do it.

But Jesus avoids arguing about Scriptural authority. He doesn’t haggle about context or interpretation.

Instead Jesus answers with common wisdom.

It is said,

‘Do not put the Lord your God to the test.’” (Luke 4:12 NRSV)

Of course in Matthew’s version Jesus says the same thing is “written” — which it is, in Deuteronomy 6:16.

It isn’t an absolute rule though: Elsewhere God tells the people explicitly,

…put me to the test” (Malachi 3:10).

It takes wisdom to sort out which opposing commandment applies. In Luke, Jesus leans on wisdom (deeply biblical wisdom) instead of arguing about the Bible.

C’mon. Everybody knows that you shouldn’t test God.

That’s probably wise advice for Christians in our contentious age. Don’t debate the Bible when your opponent acts like the devil.

So what is this third temptation really about?

But I think the real temptation here was to misuse his authority — to exploit the power he held as the Son of God for himself rather than for his mission to serve.

Whether Paul had this scene in mind or not as he wrote to the church in Philippi, his comments certainly apply. Paul noted the mindset of Christ. Jesus, he said,

…though he was in the form of God,

did not regard equality with God

as something to be exploited…” (Philippians 1:6 NRSV)

Jesus didn’t grasp his own authority and use it for public display, to prove himself against the devil, or to please himself. Instead he always used the power of God to serve the people. He

…emptied himself,

taking the form of a slave,

being born in human likeness.

And being found in human form,

he humbled himself

and became obedient to the point of death—

even death on a cross.” Philippians 2:7-8 NRSV)

And that’s even better advice today. If you hold authority, or have power over others, don’t exploit it. You are there to serve — to live out the will of Christ.

Whether Jesus’ temptations of identity, allegiance, and authority are the besetting issues of our age and our culture or not, there is wisdom to be mined from his response to them.

++++++++++++

My annual lenten prayer class is open for registration — but only through Ash Wednesday. We’ll work on the Jesus Prayer and other classic Christian ways of praying that help to bring focus to the life of prayer. If you want full information, or to sign up, click on this button:

(This post contains affiliate links.)

The post Monday Meditation: RCL Year C, 1st Sunday of Lent, Luke 4:1-13 appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

February 28, 2019

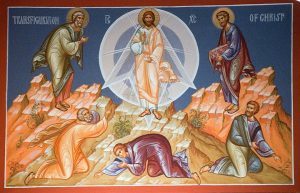

Monday Meditation: RCL Year C, Transfiguration, Luke 9:28-36

Transfiguration (CC by Ted-SA 2.0)

Transfiguration (CC by Ted-SA 2.0)This Sunday Western Christianity celebrates the “Transfiguration.” The Revised Common Lectionary gives us the story from Luke 9:28-36, because it is “Year C” when Luke’s Gospel is the focus.

Just Luke 9:28-36 for Me Please

The lectionary includes an optional extension of the reading, Luke 9:37-43a. I’m not going to discuss it. In Luke’s chronology that story is a day later, and I find the Transfiguration is absolutely fascinating. Plus I suspect it is way too easy for modern and post-modern minds to want to skip past such a strange and miraculous story.

The Transfiguration — Window into Hidden Truth

You know the story, right? Jesus takes Peter, James, and John up the mountain, so they can watch while he is transformed into a being of light.

Not so fast, bucko.

First off, the reason he went up the mountain was to pray. He seems to do that often enough after a busy day of ministry. (Not a bad idea for his followers when you think about it.)

And sometimes when he went up to pray he wanted some company. If Gethsemane is the model, then it doesn’t mean he wanted to sit in a circle and all pray out loud together. Think instead of the Desert Fathers and Mothers who went far from the crowds to pray “alone” but seem to have often been near enough to other hermits for company.

More important than the reason for their heading uphill is what happened when they got there.

Was Jesus transformed? Or were their eyes allowed to see what is normally hidden?

And while he was praying, the appearance of his face changed, and his clothes became dazzling white.

Suddenly they saw two men, Moses and Elijah, talking to him. They appeared in glory …” (Luke 9:29-31)

Either way, I think the great thing about the Transfiguration scene is that the Apostles saw something deeply true — several things, really. They saw with their eyes what they had been growing to believe in their hearts: This Jesus whom they followed was more than an ordinary man.

What might you and I see if our eyes were opened to see that each person around us is created in the image of God?

What Peter, James, and John saw was something far more: Jesus was not, like you and me, created according to the pattern, “in” the image of God. Rather they saw Jesus who actually “is” the image of God — the pattern himself, of whom each of us is a damaged copy.

At the very best you and I are like a photocopy of a photocopy, losing some of the details in the process.

More realistically, we are a smudged copy, with our nature damaged by the sin of humanity, and more particularly by our own bad choices.

But on the mountain the Apostles looked at Jesus with at least some of the veil lifted. They saw God in the flesh, shining in glory.

The Context — After Advanced Training

I suspect I’m not the only one who wishes God provided revelations of his glory a bit more often — like, maybe, to me.

What can we say about Jesus’ choice to make this revelation when, and to whom, he did?

It comes to those who followed Jesus first and remained closest to him throughout.

It comes after they had listened to Jesus teaching and watched him working for a long while.

Notably it comes after Jesus had not only called them as disciples (“learners”) but commissioned them as Apostles (“sent ones”). (Luke 6:12-13)

It comes after Jesus had actually empowered them and sent them out on their first mission, during which they took risks and God performed wonders through them. (Luke 9:1-6)

Significantly it comes after they returned from their mission and confessed Jesus to be God’s Messiah. (Luke 9:20)

All this to say the three who saw Jesus’ Transfiguration were not just any old believers. They were the chosen among the chosen, well advanced in training, in faith, and in service.

The Cloud — the Place of Revelation

I’m sure they were baffled. Peter’s odd suggestion makes that plain, even without Luke’s explanation at the end:

Peter said to Jesus,

‘Master, it is good for us to be here;

let us make three dwellings,

one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah’

—not knowing what he said.” (Luke 9:33 NRSV)

In all the attention we give to the shining light of the Transfiguration, we tend to miss the darkness that follows.

While he was saying this, a cloud came and overshadowed them; and they were terrified as they entered the cloud.” (Luke 9:34 NRSV)

After the gift of seeing so much, they suddenly could see nothing — everything was a fog.

But that darkness was also a gift.

To prove that darkness is a gift I could point you to the classic 14th century English book on prayer, The Cloud of Unknowing or to its ancient predecessors, Gregory of Nyssa’s Life of Moses, or the work of Pseudo-Dionysius.

All of these would tell you that our senses, which God created, are not capable of grasping the God who created us. Our senses grasp creation, and God is not part of creation. When we are in direct contact with God we are beyond our senses.

Gregory of Nyssa uses the image of ascending a mountain to meet God, as Moses did at Sinai as a model for darkness in God’s presence — and The Cloud of Unknowing does something very similar.

It’s like when I was hiking in the Cascade foothills as a teenager. We went up (imagine Moses genuinely closer to the presence of God) but we found the top of the mountain enshrouded in cloud. Our senses saw nothing, though God was really there.

So, my friend, if you pray and feel nothing, see nothing, hear nothing, do not despair: you are like Peter, James, and John after the Transfiguration.

You are in the presence of God. That’s a gift. But God’s presence is not something your senses can receive.

Luke shows us that it is indeed a gift because while their sight was blinded by the cloud, God spoke audibly:

This is my Son, my Chosen; listen to him!” (Luke 9:35 NRSV)

They saw a Transfiguration that confused them. But in the darkness of the cloud, they came to know what it meant: Jesus, whom they followed and loved, whom they confessed to be the Messiah, is actually even more than that: he is God’s own Son.

It’s a bit frustrating: We want God to show us everything clearly, to speak with absolute certainty. Like it or not, God choses to speak in the terrifying confusion of darkness.

The Meaning — Crucifixion and Resurrection as New Exodus

What, though, about those other guys at the Transfiguration?

Suddenly they saw Moses, the lawgiver, the one who parted the waters to lead the people of Israel out of their slavery in Egypt.

Suddenly they saw Elijah, the prototypical prophet who parted the waters so he and his disciple could cross over .

And what did Jesus talk about with the embodiment of the Old Testament, the Law and the Prophets, in glory?

They appeared in glory and were speaking of his DEPARTURE, which he was about to accomplish at Jerusalem.” (Luke 9:31 NRSV)

The English translations hide the most significant word here.

More literally,

They…were speaking of his EXODUS, which he was about to accomplish at Jerusalem.

Jesus wasn’t just about to “depart” from Jerusalem.

This was a new Exodus.

Jesus was about to lead his people out of slavery like Moses had led the Israelites. But this would not be out of earthly bondage in physical chains. Jesus would lead humanity out of its slavery to its own broken nature, to sin, to the flesh and its twisted passions.

Jesus was about to lead his people through the waters (aka through our baptism into Christ) like Moses and Elijah had led people through the waters.

When Jesus went to Jerusalem, he would conquer death by death, raising up a renewed human nature, to be transformed from glory into glory, renewed in his own image.

That’s what’s so cool about the Transfiguration.

++++++++++++

My annual lenten prayer class is open for registration — but only through Ash Wednesday. We’ll work on the Jesus Prayer and other classic Christian ways of praying that help to bring focus to the life of prayer. If you want full information, or to sign up, click on this button:

(This post contains affiliate links.)

The post Monday Meditation: RCL Year C, Transfiguration, Luke 9:28-36 appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

February 21, 2019

Monday Meditation: RCL Year C, 7th Sunday after Epiphany, Luke 6:27-38

The Homeless, Paris (CC by Alex Proimos 2.0)

The Homeless, Paris (CC by Alex Proimos 2.0)The Gospel for the 7th Sunday after Epiphany (Luke 6:27-38) continues Jesus’ “Sermon on the Plain.” It is the parallel to the “Sermon on the Mount” in Matthew but the two are different in content as well as in location.

The one thing they have pretty much in common is that while a crowd, a multitude even, is around, Jesus speaks his sermon specifically to his disciples — and here especially to the recently chosen Twelve Apostles (Luke has 6:13).

Classic Evangelism

I think of this as a parallel to the perennial approach to evangelism of mainline Protestant and pre-Reformation churches:

The community gathers as disciples on Sunday morning.

The pastor preaches and teaches on the assumption that most hearers are already followers of Jesus.

They aren’t called to a first-time faith commitment.

Visitors are welcome — indeed the congregation eagerly hopes for growth. The more imaginative churches will sometimes actively invite them. (Really. This can happen.)

But the visitors don’t get a special evangelistic message. They hear what disciples are taught, and eventually decide whether they want to join them in following Jesus.

Luke 6:27-38: Not the Law but the Kingdom

When you compare Jesus’ sermon in Luke with Jesus’ sermon in Matthew you find a very interesting difference:

In Matthew 5 these instructions are explicitly reinterpretations of the Law of Moses. The frame is along the lines of “You have heard that it is written… but I say to you…”

In Luke 6 there is no such reference point. Jesus is instead teaching on his own initiative, teaching his radical vision of the Kingdom of God. And he has a lot to say.

Most of it is a radically joyful vision of generosity.

Sure, there are some little bits that chide the disciples for being prone to do no more than anybody else:

loving those who love us back,

doing good to those who do us good,

and lending to those who will have the resources and responsibility to repay us.

But if you forget Matthew and the Law, and cover up verses 32-34, the whole thing rolls out with a kind of giggly joy in blessing everyone no matter what, loving your neighbor without any exceptions.

It’s the kind of rare, absurdly happy Christian virtue that historically you almost only find in St. Francis of Assisi.

It all builds toward Jesus’ exuberant and, you might say, hedonistic argument for generous giving:

…give,

and it will be given to you.

A good measure,

pressed down,

shaken together,

running over,

will be put into your lap;

for the measure you give

will be the measure you get back.” (Luke 6:38 NRSV)

I think the whole passage is best read in a sort of giddy tone, with Jesus showing the way to the kind of joy most of us never find — the joy in a life poured out in love and self-giving. To me it sounds like good news, but news of a kingdom that is still off in the distance.

That biblical theme of bubbling, boiling joy is, I think, usually muted by the ponderous tone in which we read the words of Jesus.

Let’s get over that.

Radical Humility, Radical Generosity

Jesus tells his disciples to live lives that are radically different from the world — even the world of good people of faith. The life Jesus calls them to — calls us to — is counter to common sense.

For instance he tells them to

Give to everyone who begs from you” (Luke 6:30 NRSV)

When traveling to some parts of the world I’ve been sternly warned not to give to any beggars at all. They come in great numbers and if you give you will be swarmed. It’s just too dangerous.

When I walk or drive down the streets of my own city I may find myself carefully looking away from people with cardboard signs or cups held out. I’ve been told to worry that they’ll use the money for the wrong things. And anyway, It’s just too overwhelming.

Jesus’ radical generosity is challenging.

For another example, Jesus tells us to

… lend, expecting nothing in return.” (Luke 6:35 NRSV)

When I go to the bank for a loan they look hard at me and my papers to be sure as they can be that I will pay back every penny — with interest.

But Jesus isn’t calling me to be a bank. He’s calling me to be a person.

Let’s face it. The text is bracing.

But that vision of radical joy is also really something…

Tantalizing Principles

Underneath this very poetic discourse on life in Christ are some hints at principles. Let me briefly note three that I find both challenging and inviting.

First:

Do to others as you would have them do to you.” (Luke 6:31 NRSV)

This is, of course, the Golden Rule. We teach it to children as if it were easy and obvious. But it’s actually pretty hard.

Sometimes the children teach us in their intuitive misapplication that it is much easier to look hard at how others treat us and take it as an invitation to treat them the same way.

Unfortunately that’s the way toward the old “eye for an eye” thing.

It takes some serious pondering to look at a real life situation and reverse the roles: “How would I want to be treated in this situation?”

And of course it takes some Christ-like love to then actually do the answer.

Second:

Do not judge, and you will not be judged” (Luke 6:37 NRSV)

That one is actually easy, except for in churches, politics, and the internet.

How hard it is not to condemn another — which is what we usually mean by “judging.” But really, offering approval is also a judgment.

What if we offered neither condemnation nor approval but simply loved people?

Personally I suspect that, especially in our churches, when we find ourselves condemning another the wise route is to take it as God’s call to our own repentance. There is something of the same sin within me or I would not have recognized it and hated it in another.

Third:

Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful.” (Luke 6:36 NRSV)

This is another place where the comparison to Matthew is illuminating.

Here’s Matthew’s version from the Sermon on the Mount:

Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect.” (Matthew 5:48 NRSV)

Note the subtle difference.

With Matthew you have to wrestle with what “perfection” means, and whether it is possible, and so forth.

With Luke you just have to look at God’s mercy. Then do it.

Like look at your life, and see the daily ways, tiny and enormous, that God has been merciful to you.

Then you just go do that mercy thing toward other people.

That call to imitate God’s mercy lies behind the Golden Rule.

That call to imitate God’s mercy lies behind the call to be radically generous.

That call to imitate God’s mercy lies behind the call to not judge.

As we say in the Jesus Prayer,

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me.

And as Jesus said to the one who identified the true neighbor as the Samaritan who showed mercy,

Go and do likewise.” (Luke 10:37 NRSV)

++++++++++++

My annual lenten prayer class will open for registration soon. We’ll work on the Jesus Prayer and other classic Christian ways of praying that help to bring focus to the life of prayer. If you want me to let you know when it opens up, click on this button and get on the waiting list!

(This post contains an affiliate link.)

The post Monday Meditation: RCL Year C, 7th Sunday after Epiphany, Luke 6:27-38 appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

February 12, 2019

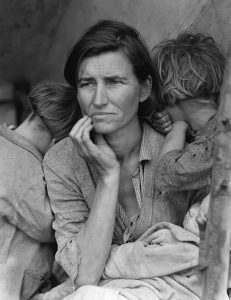

Monday Meditation: RCL Year C, 6th Sunday after Epiphany, Luke 6:17-26

Destitute Pea Pickers in California. Mother of Seven Children. by Dorothea Lange (public domain)