Gene Edward Veith Jr.'s Blog, page 462

September 21, 2012

Sitting out the election?

I’ve talked to quite a few people who say they are planning to just sit out this election. They refuse to vote for Obama, but they don’t like Romney, whether because he’s a Mormon or no true conservative or a tone-deaf bumbler or the same old politician or whatever.

The ones I’ve talked to generally vote Republican, so if there are many such folks who are refusing to vote, that could make a big difference in a close election.

Are any of you leaning in that direction?

Is not voting for Romney a vote for Obama? And if so, why not just vote for Obama? (If I did that, I would be accepted back into the bosom of my family, I would put the shades of my Democratic ancestors to rest, and I would eliminate the pang of unjustified guilt I always feel when I vote Republican.)

Plantinga on Science, Naturalism, and Faith

Alvin Plantinga is a highly-respected philosopher, respected even by those who disagree with him. An evangelical, Reformed Christian, Plantinga has written a new book, Where the Conflict Really Lies: Science, Religion, and Naturalism.

It has received a glowing review from Thomas Nagel, an atheist–in the New York Review of Books, no less–in which he says that Plantinga’s arguments help him to realize that Christians are, in fact, rational. And that his own side has some explaining to do.

The gulf in outlook between atheists and adherents of the monotheistic religions is profound. We are fortunate to live under a constitutional system and a code of manners that by and large keep it from disturbing the social peace; usually the parties ignore each other. But sometimes the conflict surfaces and heats up into a public debate. The present is such a time.

One of the things atheists tend to believe is that modern science is on their side, whereas theism is in conflict with science: that, for example, belief in miracles is inconsistent with the scientific conception of natural law; faith as a basis of belief is inconsistent with the scientific conception of knowledge; belief that God created man in his own image is inconsistent with scientific explanations provided by the theory of evolution. In his absorbing new book, Where the Conflict Really Lies, Alvin Plantinga, a distinguished analytic philosopher known for his contributions to metaphysics and theory of knowledge as well as to the philosophy of religion, turns this alleged opposition on its head. His overall claim is that “there is superficial conflict but deep concord between science and theistic religion, but superficial concord and deep conflict between science and naturalism.” By naturalism he means the view that the world describable by the natural sciences is all that exists, and that there is no such person as God, or anything like God.

Plantinga’s religion is the real thing, not just an intellectual deism that gives God nothing to do in the world. He himself is an evangelical Protestant, but he conducts his argument with respect to a version of Christianity that is the “rough intersection of the great Christian creeds”—ranging from the Apostle’s Creed to the Anglican Thirty-Nine Articles—according to which God is a person who not only created and maintains the universe and its laws, but also intervenes specially in the world, with the miracles related in the Bible and in other ways. It is of great interest to be presented with a lucid and sophisticated account of how someone who holds these beliefs understands them to harmonize with and indeed to provide crucial support for the methods and results of the natural sciences.

Plantinga discusses many topics in the course of the book, but his most important claims are epistemological. He holds, first, that the theistic conception of the relation between God, the natural world, and ourselves makes it reasonable for us to regard our perceptual and rational faculties as reliable. It is therefore reasonable to believe that the scientific theories they allow us to create do describe reality. He holds, second, that the naturalistic conception of the world, and of ourselves as products of unguided Darwinian evolution, makes it unreasonable for us to believe that our cognitive faculties are reliable, and therefore unreasonable to believe any theories they may lead us to form, including the theory of evolution. In other words, belief in naturalism combined with belief in evolution is self-defeating. However, Plantinga thinks we can reasonably believe that we are the products of evolution provided that we also believe, contrary to naturalism, that the process was in some way guided by God.

Nagel gives a very clear summary of Plantinga’s epistemology, which emphasizes that there are different kinds of “warrants” for beliefs. Faith itself, Plantinga argues, is such a warrant:

Faith, according to Plantinga, is another basic way of forming beliefs, distinct from but not in competition with reason, perception, memory, and the others. However, it is a wholly different kettle of fish: according to the Christian tradition (including both Thomas Aquinas and John Calvin), faith is a special gift from God, not part of our ordinary epistemic equipment. Faith is a source of belief, a source that goes beyond the faculties included in reason.God endows human beings with a sensus divinitatis that ordinarily leads them to believe in him. (In atheists the sensus divinitatis is either blocked or not functioning properly.)2 In addition, God acts in the world more selectively by “enabling Christians to see the truth of the central teachings of the Gospel.”

If all this is true, then by Plantinga’s standard of reliability and proper function, faith is a kind of cause that provides a warrant for theistic belief, even though it is a gift, and not a universal human faculty. (Plantinga recognizes that rational arguments have also been offered for the existence of God, but he thinks it is not necessary to rely on these, any more than it is necessary to rely on rational proofs of the existence of the external world to know just by looking that there is beer in the refrigerator.)

It is illuminating to have the starkness of the opposition between Plantinga’s theism and the secular outlook so clearly explained. My instinctively atheistic perspective implies that if I ever found myself flooded with the conviction that what the Nicene Creed says is true, the most likely explanation would be that I was losing my mind, not that I was being granted the gift of faith. From Plantinga’s point of view, by contrast, I suffer from a kind of spiritual blindness from which I am unwilling to be cured. This is a huge epistemological gulf, and it cannot be overcome by the cooperative employment of the cognitive faculties that we share, as is the hope with scientific disagreements.

Faith adds beliefs to the theist’s base of available evidence that are absent from the atheist’s, and unavailable to him without God’s special action. These differences make different beliefs reasonable given the same shared evidence. An atheist familiar with biology and medicine has no reason to believe the biblical story of the resurrection. But a Christian who believes it by faith should not, according to Plantinga, be dissuaded by general biological evidence. Plantinga compares the difference in justified beliefs to a case where you are accused of a crime on the basis of very convincing evidence, but you know that you didn’t do it. For you, the immediate evidence of your memory is not defeated by the public evidence against you, even though your memory is not available to others. Likewise, the Christian’s faith in the truth of the gospels, though unavailable to the atheist, is not defeated by the secular evidence against the possibility of resurrection.

via A Philosopher Defends Religion by Thomas Nagel | The New York Review of Books.

Read the whole review.

For the purposes of our discussion, could we make some topics off-limits? First, please do not dismiss Plantinga as a “theistic evolutionist”; he may be one, but I think that’s too simplistic, and he is also giving some “warrants” for creationism. Second, let’s not get into the debate here between “evidentialist” and “presuppositionalist” apologetics. There is actually some of both here, as Plantinga is supporting the reality of objective evidence as well as the fact–which Lutherans, at least, must not deny–that faith is a gift. The ultimate cause of atheism, as Plantinga says and as the atheist Nagel admits, is “spiritual blindness.” Finally, let’s not have any attacks on Plantinga as a Calvinist. (Comments that violate these terms may be deleted.)

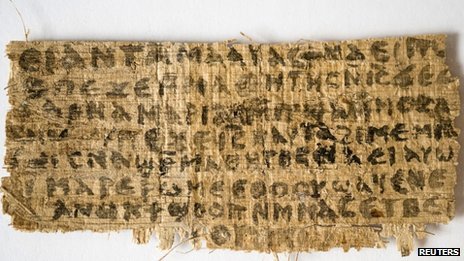

Jesus’ Wife

I’m kind of behind, with my surgery and all, so this has already gone around, but we must post it. Scholars have found a small fragment in the Coptic language from ancient Egypt that has Jesus referring to “my wife.” Now first of all, as the historian who made the translation insists, this does NOT prove the thesis of the Da Vinci Code, nor does it prove that Jesus did, in fact, have a wife, since this was written centuries after his time on earth and it has affinities to Gnostic texts. But still, let’s look at the story:

A historian of early Christianity at Harvard Divinity School has identified a scrap of papyrus that she says was written in Coptic in the fourth century and contains a phrase never seen in any piece of Scripture: “Jesus said to them, ‘My wife …’ ”

The faded papyrus fragment is smaller than a business card, with eight lines on one side, in black ink legible under a magnifying glass. Just below the line about Jesus having a wife, the papyrus includes a second provocative clause that purportedly says, “she will be able to be my disciple.”

The finding was made public in Rome on Tuesday at the International Congress of Coptic Studies by Karen L. King, a historian who has published several books about new Gospel discoveries and is the first woman to hold the nation’s oldest endowed chair, the Hollis professor of divinity.

The provenance of the papyrus fragment is a mystery, and its owner has asked to remain anonymous. Until Tuesday, Dr. King had shown the fragment to only a small circle of experts in papyrology and Coptic linguistics, who concluded that it is most likely not a forgery. But she and her collaborators say they are eager for more scholars to weigh in and perhaps upend their conclusions.

Even with many questions unsettled, the discovery could reignite the debate over whether Jesus was married, whether Mary Magdalene was his wife and whether he had a female disciple. These debates date to the early centuries of Christianity, scholars say. But they are relevant today, when global Christianity is roiling over the place of women in ministry and the boundaries of marriage.

The discussion is particularly animated in the Roman Catholic Church, where despite calls for change, the Vatican has reiterated the teaching that the priesthood cannot be opened to women and married men because of the model set by Jesus.

Dr. King gave an interview and showed the papyrus fragment, encased in glass, to reporters from The New York Times, The Boston Globe and Harvard Magazine in her garret office in the tower at Harvard Divinity School last Thursday.

She repeatedly cautioned that this fragment should not be taken as proof that Jesus, the historical person, was actually married. The text was probably written centuries after Jesus lived, and all other early, historically reliable Christian literature is silent on the question, she said.

But the discovery is exciting, Dr. King said, because it is the first known statement from antiquity that refers to Jesus speaking of a wife. It provides further evidence that there was an active discussion among early Christians about whether Jesus was celibate or married, and which path his followers should choose.

“This fragment suggests that some early Christians had a tradition that Jesus was married,” she said. “There was, we already know, a controversy in the second century over whether Jesus was married, caught up with a debate about whether Christians should marry and have sex.”. . .

[Scholars] examined the scrap under sharp magnification. It was very small — only 4 by 8 centimeters. The lettering was splotchy and uneven, the hand of an amateur, but not unusual for the time period, when many Christians were poor and persecuted. . .

The piece is torn into a rough rectangle, so that the document is missing its adjoining text on the left, right, top and bottom — most likely the work of a dealer who divided up a larger piece to maximize his profit, Dr. Bagnall said.

Much of the context, therefore, is missing. But Dr. King was struck by phrases in the fragment like “My mother gave to me life,” and “Mary is worthy of it,” which resemble snippets from the Gospels of Thomas and Mary. Experts believe those were written in the late second century and translated into Coptic. She surmises that this fragment is also copied from a second-century Greek text.

The meaning of the words, “my wife,” is beyond question, Dr. King said. “These words can mean nothing else.” The text beyond “my wife” is cut off.

Dr. King did not have the ink dated using carbon testing. She said it would require scraping off too much, destroying the relic. She still plans to have the ink tested by spectroscopy, which could roughly determine its age by its chemical composition.

Dr. King submitted her paper to The Harvard Theological Review, which asked three scholars to review it. Two questioned its authenticity, but they had seen only low-resolution photographs of the fragment and were unaware that expert papyrologists had seen the actual item and judged it to be genuine, Dr. King said. One of the two questioned the grammar, translation and interpretation.

Ariel Shisha-Halevy, an eminent Coptic linguist at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, was consulted, and said in an e-mail in September, “I believe — on the basis of language and grammar — the text is authentic.” [That is, not a modern forgery.]

Major doubts allayed, The Review plans to publish Dr. King’s article in its January issue.

via Historian Says Piece of Papyrus Refers to Jesus’ Wife – NYTimes.com. That site includes a translation of the full, though fragmentary text.

Mollie Hemingway posts a compendium of evidence that points to forgery.

But here is the point: Jesus did and does have a wife: Her name is the CHURCH.

September 20, 2012

But now I see

Things have hard edges. The leaves on a tree are distinct from each other. Each pieces of gravel on a path is separate from the others. Faces in a crowd don’t blur together. Who knew?

Those who think there are no boundaries between right and wrong, true and false, beautiful and ugly; the blurrers of distinctions; those who think there are only shades of grey; the Hindu sages and New Age gurus who think “all is one”–these people are not just making philosophical errors. They just need cataract surgery!

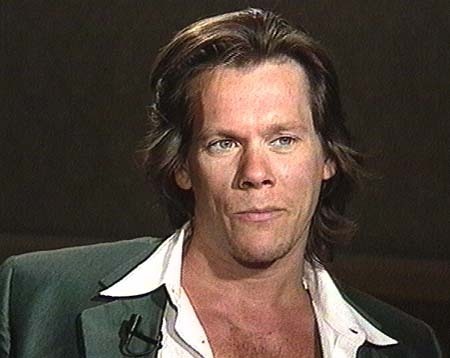

Degrees of separation

Forget Google Earth, Google Street View, and those proposed Google goggles. Here is Google’s coolest feature: Google will now calculate how many degrees of separation a person is from Kevin Bacon.

It is the party game beloved of cinephiles everywhere, one which rewards detailed knowledge of the career of one of the finest actors never to receive an Oscar nomination. And now it is even easier to play: Google has built Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon into its search system.

Devised in January 1994 by a trio of students at Pennsylvania’s Albright college, the original game was based on the idea that it is always possible to connect every movie actor in the world back to the Footloose star in no more than six associations. A website, board game and book later emerged and an initially reluctant Bacon eventually embraced the phenomenon by launching his own site, SixDegrees.org, to foster charitable donations.

To use Google’s system, the user simply types in the words “Bacon number” followed by the name of the actor. By way of example, typing “Bacon number Simon Pegg” reveals that Bacon and the British actor are linked by Tom Cruise, because the latter appeared in 1992′s A Few Good Men with Bacon and in 2006′s Mission: Impossible III with Pegg. Pegg therefore has a Bacon number of two, indicating two degrees of separation.

Lead engineer Yossi Matias said the project was about showcasing the power of Google’s search engine by flagging up the deep-rooted connections between people in the film industry. “If you think about search in the traditional sense, for years it has been to try and match, find pages and sources where you would find the text,” he told the Hollywood Reporter. “It’s interesting that this small-world phenomena when applied to the world of actors actually shows that in most cases, most actors aren’t that far apart from each other. And most of them have a relatively small Bacon number.”

By way of example, type French Oscar-winner Marion Cotillard’s name into the system and it is revealed that she has a Bacon number of two, while Humphrey Bogart, who died in 1957, nevertheless has a Bacon number of just three.

via Google builds Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon into its search system | Film | guardian.co.uk.

The Google algorithm (someone please explain how it works) just works for Hollywood figures, which is the original game, though one variation tries to connect anyone on earth to Mr. Bacon. I, for example, have a Bacon number of four: (1) The wife of a former colleague is the daughter of the man who did the make-up on Citizen Kane. (2) He worked for Orson Welles, who produced, directed, and acted in Citizen Kane. (3) Google tells me that Orson Welles appeared with Jack Nicholson in A Safe Place. (4) And that Jack Nicholson and Kevin Bacon appeared in A Few Good Men.

Another variation proposes that there are no more than six degrees of separation (or maybe a few more) between any two people in the world. For example, what chain of people who have met or have had a direct personal contact with each other might connect me to, say, a hypothetical Chinese peasant named Chen who lives in the Jiangxi province? (1) When I was in high school, I shook the hand of Senator Eugene McCarthy. (2) He shook the hand of Richard Nixon. (3) Nixon shook the hand of Mao Zedong. (4) Chairman Mao knew the members of his Communist Politburo. (5) The representative of the Jiangxi province worked with the Secret Police. (6) One of whose members doubtless spied on Chen and his parents.

I don’t know if that always works, of course. I suppose it’s based on the exponential calculations that perhaps someone could explain for us. (Is it that if each person has met a thousand people, six degrees would mean 1000 to the 6th power, or 1,000,000,000,000,000,000, a number that would require a great deal of overlap since the world’s population is only about 7,000,000,000.)

I think it shouldn’t count if your only contact with a person is reading a book or article that was written by that person. But if you comment on the person’s blog, that does count, like talking to someone over the phone. So you can add onto my degrees of separation with Kevin Bacon.

Do any of you have any other interesting degrees of separation that the rest of us could then appropriate?

Why do we even have a president?

Historian Kenneth C. Davis looks at the origin of the office of the President, something our Founders went round and round about at the Constitutional Convention.

In that steamy Philadelphia summer of 1787, as the Constitution was secretly being drafted and the plan for the presidency invented — “improvised” is more apt — the delegates weren’t sure what they wanted this new office to be. To patriots who had fought a war against a king, the thought of one person wielding great power, at the head of a standing army, gave them the willies.

Still, Hamilton asserted in the Federalist Papers that this experimental executive must have “energy” — a quality characterized by “decision, activity, secrecy and dispatch.” Hamilton knew that the times demanded bold action. Operating under the Articles of Confederation, a weak Congress had dithered through crisis and conflict, unable to collect taxes or raise an effective army. And the presidents of Congress — 14 of them from 1774 to 1788 — wielded nothing more threatening than a gavel. They couldn’t even answer a letter without congressional approval.

As the delegates to the Constitutional Convention sweltered behind closed windows, in the same Pennsylvania State House where the Declaration of Independence had been adopted 11 years earlier, they disagreed about many things. But no issue caused greater consternation than establishing an executive office to run the country.

Would this executive department be occupied by one man or a council of three? What powers would the executive have? How long would he hold office? How would the executive be chosen? And how would he be removed, if necessary? (Without an answer to this question, Ben Franklin warned, the only recourse would be assassination.)

On these questions, the record points down a tortuous path filled with uncertainty and sharp division. While some delegates feared creating a presidency that could become a “fetus of monarchy,” others called for an executive who could negotiate treaties and make appointments — or command an army if the nation was threatened. Or at least answer the mail. . . .

Another hotly contested question was who would choose the executive. Some, such as Connecticut’s Roger Sherman, thought democracy was one short step from mob rule. “The people . . . should have as little to do as may be about the government,” Sherman asserted. “They lack information and are constantly liable to be misled.”

While Wilson offered direct election by the people, some preferred allowing the national legislature to make the choice. This idea riled another key framer, Pennsylvania’s Gouverneur Morris, a wealthy transplanted New Yorker, who thought that election by the legislature would lead only to “intrigue, cabals and faction.”

As the debates bumped along through the summer, there was one certainty. As Franklin said early in June, “The first man put at the helm will be a good one.” No one doubted that he meant George Washington, sitting in front of the room and presiding over the meeting. Despite any other squabbles, the beloved leader of the American Revolution would occupy the office they later decided to call “president,” a word rooted in the Latin “praesidens” (meaning “to sit before”) and first used in America at Harvard in 1640.

Apart from that, many burning questions were still unsettled in late August, when, in timeworn congressional tradition, the delegates punted. The questions of the executive were handed over to a Committee of Eleven, which included a delegate from each of the states in attendance and dealt with a variety of issues left unresolved by the convention as a whole. On Sept. 4, the committee put forward a plan for a president chosen for a four-year term, with the authority to make treaties and appointments (subject to Senate approval), among other loosely specified powers. He would command the army, but Congress would declare war. And they proposed a voting system that placed the choice in the hands of “electors” whose selection would be left to the legislatures of the individual states, later to be called the Electoral College.

“Two days later,” Yale historian Robert A. Dahlnoted, “the impatient delegates adopt this solution,” adding, “this strange record suggests . . . a group of baffled and confused men who finally settle on a solution more out of desperation than confidence.”

via Why do we have a president, anyway? – The Washington Post.

I still feel that way with most presidential elections! Is there a better way? Might we try the three-man panel? The Prime Minister model, with the chief executive being the leader of the majority party of the legislature? (This is what most of the world’s democracies do, with just a very few having our kind of president.) Should we have made George Washington king? Or what?

Now a French magazine ridicules Mohammad

First an American puts up a YouTube video inflaming the Muslim world and now a French magazine has published cartoon inflaming the already inflamed Muslim world.

A French magazine ridiculed the Prophet Mohammad on Wednesday by portraying him naked in cartoons, threatening to fuel the anger of Muslims around the world who are already incensed by a film depiction of him as a lecherous fool.

The drawings in satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo risked exacerbating a crisis that has seen the storming of U.S. and other Western embassies, the killing of the U.S. ambassador to Libya and a deadly suicide bombing in Afghanistan.

Riot police were deployed to protect the magazine’s Paris offices after it hit the news stands with a cover showing an Orthodox Jew pushing the turbaned figure of Mohammad in a wheelchair.

On the inside pages, several caricatures of the Prophet showed him naked. One, entitled “Mohammad: a star is born”, depicted a bearded figure crouching over to display his buttocks and genitals.

The French government, which had urged the weekly not to print the cartoons, said it was temporarily shutting down premises including embassies and schools in 20 countries on Friday, when protests sometimes break out after Muslim prayers.

via Cartoons in French weekly fuel Mohammad furor – Yahoo! News Canada.

So is this freedom of the press or religious bigotry? Or both? Is there a point at which religious bigotry can become an infringement of freedom of religion? Are elements in the West–France, no less! and what’s been coming out from the ultra-tolerant Danes and the Dutch! — coming together in an anti-Islamic reaction?

September 18, 2012

Back under the knife

Having completed several weeks of recovery from cataract surgery, we do it all again starting today, as my left eye gets operated on.

Despite the forced inactivity, I was able to keep the blog going pretty well, so I hope can do the same this time. This eye, though, will be corrected for near vision–the other one was for distant vision–so this operation may affect me more in reading and blogging, at least for a few days until the vision stabilizes. When that happens, I should see really well in both eyes. But if I’m not able to blog at my normal pace, you’ll know what has happened.

The plan, after taking out the cataracts, is to put in new artificial lenses that will correct my vision so that I might not even need glasses. But it will work like this: My right eye will be for distant vision. My left eye will be for near vision. My brain supposedly will work the board, cutting from one camera/eye to the other. This is called “monovision,” and I’m told that quite a few people with contact lenses have this arrangement.

But isn’t “stereo” better than “mono”? If I just use one eye at a time, won’t that throw off my depth perception? Will I be able to see 3-D movies? If not, I don’t really mind, since I have never seen 3-D effects in a movie that I liked, with the exception of the Michael Jackson short film at Disneyland, and this will save me a lot of money in extra ticket prices. But I’d sort of like to see 3-D effects in real life.

Would glasses let me use both eyes together? I haven’t been wearing them since the first surgery since the prescription isn’t valid anymore, and I realize that I feel weird not wearing the things. I actually like wearing glasses. I hate to give them up, especially since the styles I first wore in 7th grade have finally come back in fashion and are defined as “hipster” frames.

I know, I know, I should have asked my doctor about all of this, but I always want to get out of the doctor’s office as soon as possible.

General Motors wants its freedom

Our little experiment in industrial socialism didn’t work quite as well as the Democrats are saying. General Motors did not pay back the bailout, and the American auto industry is not exactly “roaring back,” as the President said. The government still owns over a quarter of all GM stock. The company wants the government to sell out, but if it does, such is the low stock price, taxpayers would lose billions. From Market Watch:

The Treasury Department is resisting General Motors’ push for the government to sell off its stake in the auto maker, The Wall Street Journal reports. Following a $50 billion bailout in 2009, the U.S. taxpayers now own almost 27% of the company. But the newspaper said GM executives are now chafing at that, saying it hurts the company’s reputation and its ability to attract top talent due to pay restrictions. Earlier this year, GM GM -1.41% presented a plan to repurchase 200 million of the 500 million shares the U.S. holds with the balance being sold via a public offering. But officials at the Treasury Department were not interested as selling now would lead to a multibillion dollar loss for the government, the newspaper noted.

via General Motors pushing U.S. to sell stake: report – MarketWatch.

Your lying eyes

Leftover from the Democratic convention, Peggy Noonan’s review:

Barack Obama is deeply overexposed and often boring. He never seems to be saying what he’s thinking. His speech Thursday was weirdly anticlimactic. There’s too much buildup, the crowd was tired, it all felt flat. He was somber, and his message was essentially banal: We’ve done better than you think. Who are you going to believe, me or your lying eyes?. . .

Beneath the funny hats, the sweet-faced delegates, the handsome speakers and the babies waving flags there was something disquieting. All three days were marked by a kind of soft, distracted extremism. It was unshowy and unobnoxious but also unsettling.

There was the relentless emphasis on Government as Community, as the thing that gives us spirit and makes us whole. But government isn’t what you love if you’re American, America is what you love. Government is what you have, need and hire. Its most essential duties—especially when it is bankrupt—involve defending rights and safety, not imposing views and values. We already have values. Democrats and Republicans don’t see all this the same way, and that’s fine—that’s what national politics is, the working out of this dispute in one direction or another every few years. But the Democrats convened in Charlotte seemed more extreme on the point, more accepting of the idea of government as the center of national life, than ever, at least to me.

The fight over including a single mention of God in the platform—that was extreme. The original removal of the single mention by the platform committee—extreme. The huge “No!” vote on restoring the mention of God, and including the administration’s own stand on Jerusalem—that wasn’t liberal, it was extreme. Comparing the Republicans to Nazis—extreme. The almost complete absence of a call to help education by facing down the powers that throw our least defended children under the school bus—this was extreme, not mainstream.

The sheer strangeness of all the talk about abortion, abortion, contraception, contraception. I am old enough to know a wedge issue when I see one, but I’ve never seen a great party build its entire public persona around one. Big speeches from the heads of Planned Parenthood and NARAL, HHS Secretary and abortion enthusiast Kathleen Sebelius and, of course, Sandra Fluke.

“Republicans shut me out of a hearing on contraception,” Ms. Fluke said. But why would anyone have included a Georgetown law student who never worked her way onto the national stage until she was plucked, by the left, as a personable victim?

What a fabulously confident and ingenuous-seeming political narcissist Ms. Fluke is. She really does think—and her party apparently thinks—that in a spending crisis with trillions in debt and many in need, in a nation in existential doubt as to its standing and purpose, in a time when parents struggle to buy the good sneakers for the kids so they’re not embarrassed at school . . . that in that nation the great issue of the day, and the appropriate focus of our concern, is making other people pay for her birth-control pills. That’s not a stand, it’s a non sequitur. She is not, as Rush Limbaugh oafishly, bullyingly said, a slut. She is a ninny, a narcissist and a fool.

And she was one of the great faces of the party in Charlotte. That is extreme. Childish, too.

via The Democrats’ Soft Extremism – WSJ.com.