Rolf Potts's Blog, page 21

November 26, 2014

Don’t sacrifice the experience for the story

Vagablogging :: Rolf Potts Vagabonding Blog

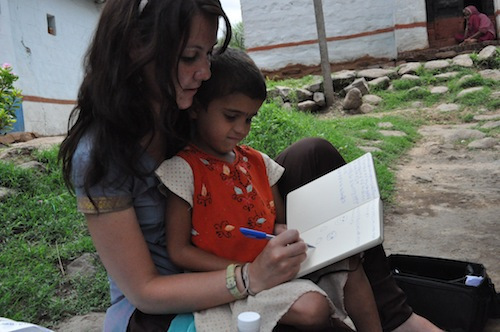

I find myself, more often than not, looking at travel experiences through a writer’s lens. Every meal, every trek, every chance meeting has the potential to be material for a travel piece. On boat rides, I think about phrasing. On long bus rides, I scroll through pictures, looking for the right one to go with the idea in my head. In cars, I pass the time by writing down thoughts that pop into my head as potential pieces.

I want to share. I want others to know what this traveling life looks like- beautiful, challenging, freeing, and difficult.

So, I plot and plan and jot down ideas. I get excited when a new experience brings up images of perfectly worded paragraphs on a screen. When I snap just the right picture, I rejoice! It’s lovely when the ideas and the words come easily.

But sometimes they don’t.

Sometimes I feel as though I have reached the absolute corners of my mind and I have nothing left to write about. Nothing of value or interest. My world starts to look quite average and I wonder who could possibly care about my excitement over finding vegetarian food in Central America.

Those are the days I most need to stop writing. Those are the days I need to get back to enjoying each moment for what it is and not worry about how I will weave it into a well-crafted article. Perfect adjectives to describe the moments take a back seat to actually experiencing the moments, as they should.

It is nice to share tales from the road. Connecting with like-minded people through the written word is wonderful. But without a connection to and enjoyment of the actual moments that are behind those stories, it’s just empty talk.

Sometimes we need to put down the pen, the computer, the camera and focus on being present.

There is no test at the end of our journey. No judgement on whether we wrote enough words or took the right pictures. There is just our own perception of what we have experienced. We need to be present for those experiences.

How do you make sure you are engaged in the experience while on the road? Do you ever get the urge to put the pen and the camera down and get reconnected with the experience of living?

Original article can be found here: Don’t sacrifice the experience for the story

November 25, 2014

Vagabonding field report: The great people and of Robe SA

Vagablogging :: Rolf Potts Vagabonding Blog

Cost per day?

For us it could have been cheap, very cheap but we decided to splash out. We hadn’t found a campsite to park on but decided to park on the sea front. Granted this wasn’t a designated spot but in such a small town no-one battered an eye lid at us. If you brought your own food then Robe has no expense.

Describe a typical day

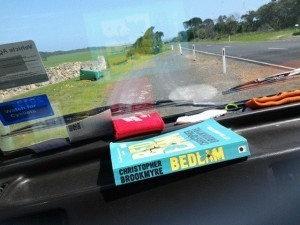

Our stay in Robe was far from typical in any sense of the word, the town like most coastal towns in South Australia thrive on its fishing port. We rolled into town from the Princes Highway just for a place to stop for the night. A small port location with panoramic views of the ocean. Today was going to be the day that we put our heads together and plan the next steps in our trip. We also had postcards to send and books to read. Above all we had every intention of exploring some of the local sites and attractions. As we had simply stumbled upon this quaint town we knew we needed to gain a little insight.

The trouble with being on the road and sometimes almost a liberation but Wi-Fi can be hard to come by. We searched the local area to find a small café to sit and drink coffee and browse the web and check emails. Feeling like I had stepped back 30 years most outlets didn’t provide Wi-Fi. The local library and information center was closed for the weekend. Fortunately and gratefully the local pub The Caledonian Inn 5 mins walk from our camper had the only internet we could use. So we snuck in to this old very cozy but very rustic public house. The structure was made up of wooden beams and old brick. We felt like we had stepped into an old country pub in Britain.

Tummies rumbling we order in a Chicken Parmagana. Australians love there parmagana you won’t fail to find a pub that does this chicken delight. Chicken in breadcrumb top with cheese, sauce, meat, veg on a layer of chips. In Australia drinks glasses are smaller, Schooners and Midis are just two names given to minature glasses, what we had been missing on our travels was a full size British (imperial) pint. It just so happens that this pub were prepared for two British backpackers to wonder in. From the top shelf they dusted of these pint glasses and filled them up with sweet nectar. The landlady was lovely we spoke about the difference between English pubs and Australian pubs and what life in robe was like.

Then the rain started.

The list of all we wanted to see had just become null and void, we couldn’t wander around Robe in the pouring rain, as the wind picked up it was coming in sideways. So we did nothing more than carry on drinking. By this point we had found a new friend in the landlady who in turn introduced us to her team. Each young person behind the bar had become fascinated in our worldwide expedition. None of them had ever strayed very far from robe or beyond a state border. A holiday for them would be a couple of hours drive in a UTE (pickup truck) and surfing for a weekend up or down the coast. Each had been to the same schools, had the same friends and hung out in the pub they worked in. Unlike us and our small-town upbringing they were happy with this small town mentality and found comfort and solace in living in a tight community.

As the night went on we were passed around each local as the new thing on the block, old women to young men each wanted to meet and talk. They all tried their best pommie (British) accent on us, many failed miserably taking to sounding more like Dick van Dyke than the Queen herself. We sank more and more drink from our imperial pints. A log fire roared and the music began. We danced in a crowded room with many strangers who had become passing friends, swapping more stories jokes and alcohol shots. Hours felt like minutes but we had found friends in Robe and staggered out the doors together into the pouring rain. The caravan rocked with the mighty winds but the Alcohol had set in and we fell right to sleep.

On a schedule and the continuing to rain the following afternoon (once we were legally able and safe to drive) we set off on our road trip

Describe an interesting conversation you had?

As I mentioned before it was great to meet then young men and women who worked behind the bar. What really struck me was there attitude to the simple pleasures in life. For me I love the sense of community that comes from a small town, having friends on your doorstep and being close to your family. The downside of a small town is the secluded nature of it and from an early age it was engrained into me that there is more to the world than the place you were born. This is why I am doing what I am doing today and travelling the world. However I look at small town life objectively, the eye opener for me was the idea that all these young people were adamant that if you have all the comforts you need and friends and family to share it with what else do you need. As much as I learned from them and their level of intrigue I hope that my stories and ambitions rubbed off on them and maybe one day they will set out on their own adventures.

What did you like? Dislike?

The rain was a dislike as it was unfortunate that we couldn’t make our way round to visit much of the Robes history. What I liked is the my fresh outlook that you don’t need to see the biggest monuments or the most beautiful beaches, in order to explore a country, meeting an Australian doesn’t let me qualify the right to know an Australian. That night gave us great insight into what the rest of the population outside of Sydney, Melbourne, Perth etc. do and how they live. We shared in the similarities of home blended with the many interesting and sometimes quirky differences. It opened our eyes to the warming nature that Australians have and to quote Jerry the guitarists, A man is a man until he’s an ar*****e then you can call him your mate.

A little advice

If time is on your side which it often is when your travelling, turn off once in a while, Robe was one of many great place we simply stumbled upon. You’ll never find the whole experience in a cosmopolitan enviroment, the diversity of Sydney or any big city even that of Uluru is not the authentic reality that we all desire. So once in a while pick a signpost and follow it, you can always turn around but you may never know what you may find at the end of that road

Where Next: Port Lincoln!!!!

Original article can be found here: Vagabonding field report: The great people and of Robe SA

November 24, 2014

Travel is not a dangerous activity

Vagablogging :: Rolf Potts Vagabonding Blog

Nine years ago, bedridden with a debilitating case of chronic Lyme disease, I examined my life. For 36 years I’d slaved away in jobs I detested because they provided me with a good living, but despite having all the material things that money could buy, I was miserable. In that rare moment of clarity, I thought, Is this all there is?

Three-plus decades after entering the work force, I was no closer to achieving my dreams of being a travel writer and photographer. Instead, I’d become ensnared in a web of mortgages, car payments, and a seeming unending desire for more “stuff.” I promised myself that, if I recovered, I would walk away from corporate life to pursue the only thing I’d ever wanted to do.

[image error]

Hiring an “Easy Rider” motorcycle to see Nha Trang, Vietnam in March, 2007

A year later, at the age of 54, I slung a backpack over my shoulder and headed out on my first round-the-world trip. I was excited and more than a little scared. Vietnam was my first destination, and for weeks my friends and family had been alarming me with stories of the dangers of the country. My first night did not go smoothly. I checked into my guest house, found an Internet cafe down the street, and settled in to work. A couple of hours later I stepped back onto the street, only to find that metal shutters had been rolled down over all the storefronts. Everything looked the same.

By the time I’d spent two weeks traveling solo around Vietnam by bus, I was confident in my ability to travel the world solo.

Rather than panic, I calmed myself with the idea that, at worst, I would have to move to another hotel for the night. I did eventually locate my guest house and, after a few minutes of banging on the metal door, woke the night watchman, who let me in. It was my first lesson in rolling with the punches. By the time I’d spent two weeks traveling solo around Vietnam by bus, I was confident in my ability to travel the world solo.

My second experience in Vietnam was even more profound. In Hanoi, I visited the War Museum and was shocked to learn that Vietnamese refer to the 20-year conflict as “The American War.” This one small fact translated into a fascination for the differences between cultures that has influenced all my subsequent travels.

In the eight years since my initial round-the-world trip, I’ve visited more than 50 countries, traveling slowly whenever possible in order to immerse in the local cultures. In 2009, I gave up my apartment and became a perpetual traveler, with no permanent home base, and I have no plans to stop anytime soon.

Standing in front of the Brandenberg Gate i n Berlin, September 2014

When people learn what I do, they often exclaim, “You’re so brave,” or ask, “Aren’t you afraid?” I tell them there is no reason to be afraid, that people the world over are more similar than they are different. Though we may wear different clothes, speak different languages, and practice different religions, at our core we all want the same things: a safe place to live, enough food to eat, freedom from oppression, and a better life for our children.

“Travel is more than the seeing of sights; it is a change that goes on, deep and permanent, in the ideas of living.” Miriam Beard

Miriam Beard, daughter of the American historians Charles and Mary Beard, said “Travel is more than the seeing of sights; it is a change that goes on, deep and permanent, in the ideas of living.” Without a doubt, travel has irrevocably changed me. I have no interest in owning a home and never purchase souvenirs. My wardrobe is limited to what fits in a 25” suitcase. Material possessions are of no interest to me. And I have never felt so free.

I now realize that my initial fears were foolish. Travel is not dangerous. Despite traveling solo to numerous developing countries where poverty is rife, I have never felt the least bit threatened. Strangers have gone out of their way to help me and even welcomed me into their homes. Lifelong friendships have resulted. Travel, more than any other activity, eliminates the fear of others whom we see as different from ourselves.

Perpetual travel is not for everyone, however, long-term travel is becoming more popular with more than just ‘gap year’ travelers. Baby boomers especially, who are healthier and more active than ever before, are looking for ways to make valuable contributions in retirement, and many are opting to do so by volunteering overseas. Having mastered the art of long-term travel, I plan to share my wealth of knowledge in this monthly column. So, whether you’re an armchair traveler or are contemplating long-term travels of your own, be sure to watch for my future articles. It should be an insightful journey.

When Barbara Weibel realized she felt like the proverbial “hole in the donut” – solid on the outside but empty on the inside, she walked away from corporate life and set out to see the world. Read first-hand accounts of the places she visits and the people she meets at Hole in the Donut Cultural Travels. Follow her on Facebook or Twitter (@holeinthedonut).

Original article can be found here: Travel is not a dangerous activity

November 23, 2014

The best travel writing has always been subjective

Vagablogging :: Rolf Potts Vagabonding Blog

“It is safe to say that the lasting travel accounts are quite subjective, that — within limits — the more subjective they are, the more readable, the more “valuable” they are. Travelers, like novelists, learned long ago the truth of Todorov’s statement of a universal law: “The best description…is the one which is not description all the way.” That is, the best description is combined with, cannot really be separated from, narration, reflection, interpretation.”

–Percy G. Adams, Travel Literature and the Evolution of the Novel (1983)

(1983)

Original article can be found here: The best travel writing has always been subjective

November 21, 2014

Retch-22 Laos in the time of cholera

Vagablogging :: Rolf Potts Vagabonding Blog

Ray, a bearded New Yorker who had recently dropped out of college to travel the world, was convinced that southern Laos was turning into a horrific cesspool of death and disease.

“I’m telling you,” he said to me as we stood outside the small ice-cream stand near the Phonsavanh Hotel in Pakse. “Cholera is completely out of control down here. A French guy I talked to in Savannakhet said the Pakse hospital was full of dead bodies.”

“Did the French guy see the dead bodies?” I asked.

“No, but he talked to a guy who saw the dead bodies.”

“And you’re sure he didn’t just talk to a guy who talked to another guy who saw the dead bodies?”

Ray looked at me with irritation. “Look, I have a sense for this kind of thing. I could tell he was serious.”

I decided to drop the big question. “So if you’re sure he was telling the truth about dead bodies in the Pakse hospital, what are you doing in Pakse right now?”

“Fuck it, man,” Ray said enthusiastically. “This is where the action is.”

By this point, I had been in Pakse for 24 hours and I was at my wits’ end. I’d been hearing the cholera rumors since coming overland from Vietnam, but I couldn’t get any hard facts. Nearly every traveler I’d met had heard there was a cholera epidemic on the Mekong flood plain south of Pakse, but not a single person had gotten this information from an official source. Many travelers were aborting their Laos travel plans and moving on, but others — like Ray — were embracing the cholera rumors with vicarious zeal. For these people, the very notion of the epidemic was enough to turn an otherwise normal trip into an adventure.

On the other hand, all the Laotian government offices and agencies in Pakse were categorically denying the existence of cholera. I visited two different government travel agencies in Pakse, and both insisted there was no problem with traveling south along the Mekong. The woman at the local health office laughed at the idea. “There are some people who have diarrhea,” she said, “but there is no cholera.” Even the officials I phoned at the U.S. Embassy in Vientiane knew nothing of the cholera rumor.

Since there was no hard evidence of an epidemic — and knowing how travelers tend to exaggerate — I continued with my plans to head downriver. As I hiked down to the river pier on the morning of my second day in Pakse, I met a Lao man named Kumsing who was working on a rural electrification project in the area. He was uncommonly friendly, and he spoke great English.

“Where are you headed?” he asked me.

“South,” I said. “I’m going to visit the 4000 Islands on the Mekong.”

Kumsing clicked his tongue. “That’s a nice area, but you have to be careful these days. I was there last week, and many of my workers got sick.”

“Was it cholera?”

“Yes, cholera. You won’t catch it if you’re careful. Not all of my workers got sick, just the careless ones.”

“How many workers were careless?”

Kumsing did some quick math. “Sixteen. But none of them died.”

“But everyone else stayed healthy — no cholera?”

“Yes, the other two are fine.”

“Other two?”

“Yes. Plus I didn’t get sick, either!”

On paper, my trip to the 4000 Islands of Laos should have been the easiest journey I’d taken all year. Not only was I returning to familiar territory (I’d traveled the Laotian Mekong in my own boat a few months previously), but I’d also come to write a story on the area for a well-paying glossy print magazine. Instead of randomly vagabonding my way down the Mekong, I would be visiting pre-selected places and interviewing people I already knew. Since southern Laos is a peaceful, enchanting region, my magazine assignment promised no hardships beyond the simple process of collecting story information.

With the objectives so clear-cut, my return to the 4000 Islands was supposed to be — as the pilots in “Catch-22″ said when referring to easy missions — a “milk run.”

In reality, it had been quite the opposite of a milk run. Before I’d ever heard rumors of cholera, the mere process of traveling overland to Laos from Vietnam had been a headache in itself. On a map it looked easy to cross into the south of Laos from the Vietnamese Central Highlands — but there were no legal customs stations along this border. So to get to Laos from the Central Highlands, I first had to take a day-long trip out of the highlands and up the coast to Danang, then wait for the next available bus to Laos via Lao Bao.

Since this road to Laos follows a treacherous route over the Annamite Mountains, I opted to take the smaller, safer, air-conditioned bus offered by a travel office in Danang. Unfortunately, the air-con bus existed only in the travel office photograph; after purchasing my ticket, I was unceremoniously dumped off at the local transit station and ushered into a huge, decrepit old DeSoto bus.

I spent 22 hours on the DeSoto, including a three-hour delay in rural Laos when the drivers stopped to unload a cache of smuggled items into two separate Nissan pickups. I arrived in Savannakhet just in time to eat, sleep and board a morning bus to Pakse, which (including a four-hour stop when the drivers dropped the transmission onto the road and had to reassemble it) took 11 hours.

I arrived in Pakse exhausted, and spent the next couple days trying to confirm the cholera rumors. When I heard Kumsing’s tale, I postponed my boat trip and went back to check with the health department.

“I just met a man from the electric company who says that 16 people got cholera last week,” I said to the woman in the office.

“That wasn’t cholera,” she told me. “Those men just had diarrhea.”

“All 16 men just happened to get diarrhea at the same time?”

“Yes,” she said. “Maybe it was food poisoning. There is no cholera in Laos.”

This sounded a tad suspicious to me, but I felt I had come too far to abandon my journey to the 4000 Islands. Grimly resolved, I returned to the pier and boarded a mid-morning freight boat bound for the island of Don Khong. Granted, I was no longer on my idealized milk-run vacation, but — whatever the facts were about cholera — I figured I’d be safe if I kept myself religiously clean and avoided the local food.

Furthermore, I was personally convinced — after six months on the road in Southeast Asia — that cholera couldn’t touch me. As with Yossarian in “Catch-22,” avoiding doom seemed a mere matter of will power, milk run or not.

Cholera couldn’t touch me, I reasoned, because I had a pure body and was as strong as an ox. Cholera couldn’t touch me because I was Tarzan, Mandrake, Flash Gordon. I was Bill Shakespeare. I was Cain, Ulysses, the Flying Dutchman; I was Lot in Sodom, Deirdre of Sorrows, Sweeny in the nightingales among trees.

I, like Yossarian in “Catch-22,” was miracle ingredient Z-247.

My journey to the 4000 Islands of Laos started splendidly. After spending the first night on Don Khong, I continued downriver to Khone island on the Cambodian border — where freshwater dolphins haunt deep pools and the Mekong suddenly crashes down into the largest complex of waterfalls in Asia. As I hiked around collecting information for my article, I sustained myself on bottled water, peeled fruit and an enormous bag of roasted peanuts. After a couple of peaceful, slow-paced days in the 4000 Islands, the notion of cholera had ceased to be a concern for me.

I probably would have forgotten about cholera entirely had I not suddenly vomited onto my shoes the morning after returning to Don Khong. I had come back to the island to tie up a few loose ends of my story, and at first it didn’t occur to me what was happening. When I vomited again a few minutes later, the gravity of the situation began to dawn on me. After I threw up for the third time, I took out my phrase book and started asking directions to the hospital.

I remember the next part only in bits and pieces. I know I kept asking people where the hospital was, and people kept pointing me up the road — but the hospital never materialized. It had rained the day before, and the humidity made the air quiver in the sunlight. As I walked, my brain rattled inside my skull like a sodden lump of clay; psychedelic fireworks burst behind my eyelids every time I doubled over with stomach cramps.

Though I didn’t know it at the time, the Don Khong hospital was nearly two kilometers outside of Khong Village. By the time a Lao motorcyclist found me squatting beneath a tree on the side of the road, I was still 200 meters away from my goal. The motorcyclist helped me to the concrete-floored hospital reception room, and I sat on a wooden bench while the staff debated what to do with me.

The hospital was constructed entirely of cinderblocks and had no window panes. Since there was no electricity on Don Khong during daylight hours, I sat in the half-light and waited. A nurse gave me a plastic bag so I wouldn’t have to run outside to vomit. Each time I retched, a few more patients wandered in from adjoining rooms to watch me. Before long, about 20 people had gathered to watch me expectorate a clear, stringy gelatin from the bottom of my stomach. As I sat there clutching my plastic bag, I half-expected one of them to ask me for my autograph.

Finally, a young Swedish doctor named Michael arrived. Michael was not really named Michael, and he wasn’t actually Swedish. But, since he was technically not supposed to be treating cholera cases in southern Laos, Michael will be Michael for the sake of this narrative.

“I see you’ve been vomiting,” Michael said, gesturing to my plastic bag. “Do you also have diarrhea?”

“Yeah, it’s killing me,” I said. “Does the hospital have anything that can stop it?”

“This hospital doesn’t have much by Western standards. Nor does this country, for that matter. Your ideal health option would be to get out of Laos as soon as possible.”

“Can the cholera kill me?”

“Technically, we can’t prove it’s cholera without doing a culture test, first. Whatever it is, it won’t kill you.”

“But we know it’s cholera,” I said. “There’s an epidemic going around, right?”

“I think the best thing for you to do right now is get out of this hospital. First we’ll find you a comfortable guest house, and there you can take oral rehydration salts until you get your strength back.”

“Has anyone died from the cholera this year? There’s lots of stories going around Pakse.”

Michael gave me a nervous look. “Like I said, we can’t call it cholera without a culture test. I know of 16 deaths so far. But those are mostly the very young and the very old. This is not something you should worry about.”

Michael got me some oral rehydration salts from the hospital storeroom and had an orderly motor me back to my room at the guest house. I stayed there and drank salt water for two days while the cholera bugs had their way with my intestines.

Though I could describe in colorful detail what cholera does to the inner workings of the human body, such exposition would be neither necessary nor tasteful. In a euphemistic nutshell, cholera renders everything that enters your body — water, bread, strawberry Pop-Tarts, etc. — into pond water. Furthermore, this pond water creation/expulsion process happens at such a terrifyingly rapid speed that I suspect Einstein himself must have suffered from cholera around the time he came up with his relativity theory. I went for hours at a time without leaving the bathroom.

When I wasn’t in the bathroom performing glorious acts of gastrointestinal alchemy, I spent my time stretched out on my bed, staring at the ceiling, which was mint green. The mint-green ceiling featured a brown metal ceiling fan — which didn’t move in the heat of the day, since the electricity didn’t come on until sunset. My bedspread was orange.

I pondered these things continuously for 48 hours.

Michael came to check on me each morning and evening. After two days, he concluded that I was strong enough to leave, and he arranged a ride to take me back to Pakse. I can’t recall ever having been so happy to see a Toyota Landcruiser.

Since my late-afternoon arrival in Pakse didn’t leave me enough time to make it to the Thai border station, I checked in to a hotel and set off to inform the local health department of my demise.

“I just caught cholera in the 4000 Islands,” I told the lady in the office. “Maybe you should warn people about going there.”

“It’s probably not cholera,” she said. “If you’re sick, maybe you should go to the hospital.”

“I’ve been to the hospital. I’ve been vomiting and I’ve had diarrhea for two days now. Trust me: I have cholera.”

“I don’t think you have cholera. Did the doctor do a culture test?”

“Look,” I cried, exasperated, “if what I have isn’t cholera, then what the hell is it?”

“Well,” she said diplomatically, “it’s probably just diarrhea, with some vomiting.”

Retreating from the health office in defeat, I walked to the Sedone restaurant and drowned my frustrations in a glass of lemonade. Keeping in mind my condition, I got a seat near the toilet. After a while, I got up and introduced myself to a guy named Doug, whom I’d overheard warning a table full of travelers about the epidemic. Doug, a Canadian on vacation from his job as an aid worker in Thailand, seemed almost pleased when I told him that I had cholera.

“I knew it would happen!” he said. “You’re the first tourist to catch it, but there’ll be more.”

“Why aren’t there official warnings?” I asked. “I tried to get some solid information before I left for the 4000 Islands, but all the government agencies were denying that cholera existed. They’re still denying it, for that matter.”

Doug smirked. “Of course they’re denying it. I have friends doing volunteer work in this part of Laos — cholera passed the culture tests a month ago. The government is keeping it quiet because this is Visit Laos Year. They don’t want to rain on the tourist parade.”

“This is the first time I’ve ever heard of a communist government lying to promote independent tourism.”

“In a way, it’s hard to blame the government for doing it. The West has encouraged Laos to go capitalist — and one of the principles of capitalism is supply and demand. In a poor country like Laos, tourism may very well be the number-one source of hard currency. Back when the epidemic started, some paper-pusher in Vientiane took one look at tourist revenues and decided right then and there that cholera did not and would not exist. Now people like you are getting exposed to cholera because the Laotian government is afraid to discourage you from coming to Laos.”

“Catch-22,” I said.

“Right. The same thing happened with AIDS in Thailand in the late 1980s. And just like in Thailand, the people who live here will bear the brunt of the problem. It’s the people living in the 4000 Islands — not you — who are going to suffer the most when doctors aren’t allowed to go down and treat them properly.”

“Sure,” I said. “I don’t need to worry about the quality of local health care when I can just go home.”

Doug grinned. “Well, technically, you can’t go home. Under international law, you aren’t allowed to cross the Thai border if you have cholera.”

“But technically,” I said, “cholera doesn’t exist in Laos.”

“Catch-22″ had finally done me a favor.

I crossed into Thailand at Chong Mek the following day. Continuing to Ubon Ratachani, I caught a night train to Bangkok. There, I checked into the modern confines of a medical clinic and began my slow recovery.

Originally published August 24, 1999 on Salon.com

Original article can be found here: Retch-22 Laos in the time of cholera

November 20, 2014

Vagabonding Case Study: Raymond Walsh

Vagablogging :: Rolf Potts Vagabonding Blog

Raymond Walsh

Age: 45

Hometown: St. John’s, Newfoundland, CANADA

Quote: “Cover the earth before it covers you.”

How did you find out about Vagabonding, and how did you find it useful before and during the trip?

I’ve had a hard copy of Vagabonding for years, and have a digital copy on my Kindle now. I used it (and still use it) mostly for inspiration more than for practical advice. It just feeds the wanderlust.

How long were you on the road?

I’m still on the road, although I do prefer slower travel now. Basing myself in a city for a few months then exploring the region works much better for me.

Where did you go?

Since leaving my corporate job behind I’ve been to Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Oman, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, South Africa, Finland, Portugal, Spain, Romania, Poland, Mexico, and the good old US of A.

What was your job or source of travel funding for this journey?

I had some money saved to see me through the start, but I run a few travel websites now and do some freelance writing so that pays the bills.

Did you work or volunteer on the road?

I worked online so all I needed was a Wi-Fi connection and I was good to go.

Of all the places you visited, which was your favorite?

That’s always such a difficult question. I used to have a quote from the movie Harvey on my desk when I worked a regular job that read, “I always have a wonderful time, wherever I am, whomever I’m with.” I think just about every destination offers something that no other can, but there are many places I’m keen to revisit. If I had to pick a couple of favorites, I’d go with Thailand, Jordan, and Oman.

Was there a place that was your least favorite, or most disappointing, or most challenging?

Vietnam was both spectacular and rough at the same time. The first overnight sleeper bus I took ended up striking and killing a woman on a moped. It was the hardest thing I’ve ever seen.

Which travel gear proved most useful? Least useful?

The most useful thing I brought was a smartphone. It’s great for maps, taking notes, photos, checking email, booking hotel rooms, and keeping in contact. Least useful thing I brought was a package of water purification tablets. Unless you’re doing a lot of trekking in the jungle, you probably won’t need them.

What are the rewards of the vagabonding lifestyle?

Not being tied down by “stuff” or “things.” Having incredible experiences in places I’ve only dreamed of. And meeting people from all walks of life changes you for the better.

What are the challenges and sacrifices of the vagabonding lifestyle?

I’d say the biggest sacrifice came down to friends and family. Yes, you do meet plenty of folks while traveling, but it’s hard sometimes when you miss milestones like birthdays, weddings, or even just dinners with your loved ones.

What lessons did you learn on the road?

I learned that no matter where you go, people are generally on your side. I learned that there are many different travel styles, and it’s up to you to decide which one suits you best. I learned that it can actually be cheaper to live a life a travel than a life of staying put. And I learned that I don’t need to fit into someone else’s idea of what my life should look like.

How did your personal definition of “vagabonding” develop over the course of the trip?

I started out with a feeling of “I have to see everything NOW!” I had to learn to slow down, and once I did I was able to enjoy it all so much more.

If there was one thing you could have told yourself before the trip, what would it be?

Just because you can’t see the path in front of you doesn’t mean the ground won’t support you. Things have a way of working out, and worry is just extra baggage you don’t need.

Any advice or tips for someone hoping to embark on a similar adventure?

I give this advice to all travellers: Be not afraid. Most people are there to help, not to harm. Be not judgmental. It’s not wrong, it’s just different. Be not an ass. Remember, you are a guest.

When and where do you think you’ll take your next long-term journey?

I’d like to pick up the pace a little more mid 2015 and see more of Asia and South America. And the Stans. They’re not going to see themselves.

Read more about Raymond on his blog, Man On The Lam , or follow him on Facebook and Twitter

Website: Man On The Lam

Twitter: @manonthelam

Are you a Vagabonding reader planning, in the middle of, or returning from a journey? Would you like your travel blog or website to be featured on Vagabonding Case Studies? If so, drop us a line at casestudies@vagabonding.net and tell us a little about yourself.

Original article can be found here: Vagabonding Case Study: Raymond Walsh

November 19, 2014

Vagabonding Case Study: Rease Kirchner

Vagablogging :: Rolf Potts Vagabonding Blog

Rease Kirchner

Age: 27

Hometown: St. Louis, Missouri USA

Quote: “[Her] goal in life was to be an echo

Riding alone, town after town, toll after toll….Remember to remember me

Standing still, in your past

Floating fast like a hummingbird.” – Wilco “Hummingbird”

(I even got a tattoo to honor it – http://indecisivetraveler.com/remembe...)

How did you find out about Vagabonding, and how did you find it useful before and during the trip?

Honestly I don’t know how I found out about it, I think it was just word of mouth/social media. I just always heard other travelers mention it.

How long were you on the road?

Not sure I ever stopped!

Where did you go?

I moved in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 2010 and stayed until 2012. I then based myself in St. Louis, Missouri (my hometown) for a couple years but ended up out of town for about 3 months out of the year. I recently moved to Fajardo, Puerto Rico which is my new home base.

What was your job or source of travel funding for this journey?

Before I moved to Argentina I worked as a Bilingual Preschool teacher and Interpreter/Translator for the school. I loved it, but it didn’t pay very well, so I also worked at a YMCA daycare and tutored several students in Spanish so I could save up lots of money. I also did some CD accounts with portions of my savings so I could cash in on interest.

Did you work or volunteer on the road?

In Argentina I did a lot of things at first, worked as an Au Pair, English teacher, and virtual assistant. Eventually I worked at an Argentine software company. Now I freelance in Spanish/English interpretation/translation, writing, tutoring, and social media.

Of all the places you visited, which was your favorite?

I really adored Rosario, Argentina. It had a lot of the city-feel stuff I loved about Buenos Aires, but it was cleaner and cheaper.

Was there a place that was your least favorite, or most disappointing, or most challenging?

Honestly my move to Fajardo, Puerto Rico has been very challenging! I thought that after doing a move Argentina, which was a whole different continent, moving to an island that is still part of the US would be fairly easy. I was wrong! It’s been really hard to set up my life here, everything from getting electricity in my house to learning how to drive more aggressively has been a challenge. It’s a beautiful place though so I know all the struggles will be worth it.

Which travel gear proved most useful? Least useful?

I don’t use a lot of travel gear, possibly because I don’t camp or hike, I’d say my 3-way USB charger has been pretty helpful though, and also my inflatable neck pillow for long flights!

What are the rewards of the vagabonding lifestyle?

I get to meet SO many amazing people. I have made such incredibly life-long friends through traveling. The bonds you make through meeting someone while on the road can sometimes link you for life. I love telling stories like “Oh I have a friend in Toronto. I met her when I was living in Buenos Aires but she was just traveling through. We met up in Mexico last year, we’ll have to catch each other somewhere else next time.” I feel like traveling has made me a more positive and loving person in some ways.

What are the challenges and sacrifices of the vagabonding lifestyle?

Well one unique challenge I have is my dog, Padfoot. I brought Padfoot with me from St. Louis, Missouri all the way to Buenos Aires, Argentina and then back again. I don’t take him on short trips, but when I moved to Fajardo, Puerto Rico the poor little guy had hop on a plane with me again. In Buenos Aires and in St. Louis I had friends who loved my dog and would always care for him when I was on trips, but now that I am in a new place, I have to find new people who will take care of my neurotic little guy while I travel around! Padfoot is such a huge part of my life that he has his own tag on my site! http://indecisivetraveler.com/tag/pad...

What lessons did you learn on the road?

Missing your flight, train, or bus is not the end of the world. I’m pretty crazy about being on time and I still get to the airport with extra time (mostly because I always get stopped for “random” screening) but I have had flights cancelled and buses severely delayed and you know what? It was fine. I either roughed it up for the night in the airport, left and explored the city, or figured out something else. You can’t stress out about stuff you cannot change.

How did your personal definition of “vagabonding” develop over the course of the trip?

I guess I never really did the backpacker thing, which is what I always had in my mind as a “vagabond.” I prefer to base myself in interesting places and then take trips to explore new places as often as I can.

If there was one thing you could have told yourself before the trip, what would it be?

Learn the metric system. Oh man, I am still the worst. I swear even after living abroad for years I still don’t understand Celsius, I just use this rhyme: 20 is hot, 15 is nice, 10 is cold, and 0 is ice.

Any advice or tips for someone hoping to embark on a similar adventure?

Save up lots of money! My move to Argentina wasn’t too pricey, but surviving until I could find stable work drained my savings. All those extra shifts I picked up really made the whole situation less stressful and more enjoyable.

When and where do you think you’ll take your next long-term journey?

I’m here right now! I moved to Fajardo, Puerto Rico in October 2014 and I’ll be here for a least a couple years! I can’t wait to explore the Caribbean and pop up to the East Coast more often!

Read more about Rease on her blog, Indecisive Traveler , or follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Website: Indecisive Traveler

Twitter: @indecisiveRease

Are you a Vagabonding reader planning, in the middle of, or returning from a journey? Would you like your travel blog or website to be featured on Vagabonding Case Studies? If so, drop us a line at casestudies@vagabonding.net and tell us a little about yourself.

Original article can be found here: Vagabonding Case Study: Rease Kirchner

November 18, 2014

Vagabonding Case Study: Elizabeth Kelsey Bradley

Vagablogging :: Rolf Potts Vagabonding Blog

Elizabeth Kelsey Bradley

Age: 31

Hometown: Antibes, France and Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin

Quote: “We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth at least the truth that is given us to understand” Picasso

How did you find out about Vagabonding, and how did you find it useful before and during the trip?

I found out about Vagabonding from a good friend of mine and fellow Dual Citizen slash Third Culture Kid, Jen Miller. I then purchase the book and have used both as a source of inspiration and as a way of seeing the world in a different way. I’ve traveled all my life so this is the lifestyle I’ve grown up with and accustomed to. Vagabonding helped me to realize it’s OK to be a nomad and helped me see a beauty in it I hadn’t seen before.

How long were you on the road?

Roughly 5 years.

Where did you go?

We moved from LA to South Korea ( near the North Korean border), Italy, Phuket, Scotland, Bangkok, and back to Phuket.

What was your job or source of travel funding for this journey?

Initially my husband taught English in Korea and then in Thailand, and I freelanced.

Did you work or volunteer on the road?

I didn’t but my husband did.

Of all the places you visited, which was your favorite?

Sadly I can’t answer that as I have no favorite place since our family embarked upon this journey, each were special and unique.

Was there a place that was your least favorite, or most disappointing, or most challenging?

The most challenging was in living in semi rural Korea. Very friendly people, but our daughter was a baby and I felt isolated and stuck inside our apartment most days. Plus, this was the time when the sub was sunk and there was much talk about war with North Korea, which was under an hour away from where we were living ( Paju). If was had started, we would be the first to be attacked which made it very hard to focus on daily life with that worry going on.

Which travel gear proved most useful? Least useful?

As stupid as it sounds, my iphone. The apps and wifi allow me to work and communicate with anyone.

What are the rewards of the vagabonding lifestyle?

It allows me to see the world in a different way, and also to be on the fringe of society. I don’t feel the pressure to fit in anywhere because I don’t have a particular home or community that makes me feel I need to fit in.

What are the challenges and sacrifices of the vagabonding lifestyle?

The lack of community and close friendships. My friends live all around the world and are not all nomads, so it can be hard to communicate about daily life and our goals/dreams for various reasons.

What lessons did you learn on the road?

I learned to see the beauty in being ‘in between’. In between societies, in between cultures and values and ideas and even citizenship.

How did your personal definition of “vagabonding” develop over the course of the trip?

I see it much more as a way of life than a fad or phase.

If there was one thing you could have told yourself before the trip, what would it be?

Work hard and focus on what you have, no matter how little. Keep going, don’t doubt yourself.

Any advice or tips for someone hoping to embark on a similar adventure?

Believe in yourself and your dreams. Learn as much as possible from each culture you visit.

When and where do you think you’ll take your next long-term journey?

Most probably somewhere in B.C., possibly Tofino or Nelson.

Read more about Elizabeth on her blog, ekbradley.net , or follow her on Facebook and Twitter

Website: E K Bradley

Twitter: @calanagear

Are you a Vagabonding reader planning, in the middle of, or returning from a journey? Would you like your travel blog or website to be featured on Vagabonding Case Studies? If so, drop us a line at casestudies@vagabonding.net and tell us a little about yourself.

Original article can be found here: Vagabonding Case Study: Elizabeth Kelsey Bradley

November 16, 2014

For expatriates, America-bashing is a kind of recreational activity

Vagablogging :: Rolf Potts Vagabonding Blog

“I’ve found that, for expatriates, America-bashing can become a kind of recreational activity (“re-creating,” in a the process, a sense of home), a way of both justifying your choices and reminding yourself, in a playful and not-too-disturbing way, of the country and culture that — despite anything and all you may do to have it otherwise — are yours. Part of the pride and pleasure of being an American, after all, is that there’s so much to make fun of.”

–Michael Blumenthal, “Western Union,” from In Brief: Short Takes on the Personal (1999)

(1999)

Original article can be found here: For expatriates, America-bashing is a kind of recreational activity

November 15, 2014

Veterans Day and Historic Military Sites

Vagablogging :: Rolf Potts Vagabonding Blog

Veterans’ Day in the US and the UK is replete with ceremonies (concerts and parades in the US, red poppies in the UK) to commemorate those who served their country in uniform. Aside from a great opportunity to thank those that fought in foreign lands, it’s a great opportunity to remember some of the historic sites that can give testament to the events they witnessed.

While some sites are now little more than quiet fields that have been reclaimed by nature, many places can still pack an educational punch that leaves the visitor still give the visitor a sense of the enormity and ruthlessness of war.

Here are a couple of my recent favorites:

Duxford Airbase and Imperial War Museum, Duxford, England

Revered as a major Royal Air Force (RAF) base during the legendary “Battle of Britain”, RAF Duxford also boasts an Imperial War Museum. With more than 200 historic aircraft ranging from rickety World War I biplanes to the B-17 Flying Fortress to the SR-71 Blackbird, the collection is arguably the finest in Europe. Also on display is part of the Imperial War Museum’s vast trove of historic photographs, uniforms and documents.

RAF Duxford exhibits

RAF Duxford, situated in bucolic countryside outside Cambridge, was founded during World War I but earned its place in history during the darkest days of World War II. In preparation for his planned invasion of Britain, Hitler launched the full might of the Luftwaffe at England’s factories and cities in 1940.

The bombs killed indiscriminately. His aim was as psychological as it was practical; he sought to terrorize the population and break Britain’s will to fight. It fell to the undermanned RAF to defend the homeland.

As the sector station for Fighter Command’s No. 12 Group, Duxford Air Base was in the thick of the battle. Casualties were immense. The pilots who fought in the Battle were enshrined in lore as “The Few”.

Historic air show at RAF Duxford

In June 1944 the planes launched from the same runways would protect the Allied fleet as it steamed toward Normandy. It would also gain fame as one of the homes of the fighter escorts for the Allied bombers that pulverized Nazi Germany’s industrial might.

RAF Duxford continued as a fighter station after the war and was decommissioned in the 1970’s. With over thirty authentic buildings recognized by the British government for their historical significance, the base was granted to the Imperial War Museum (IWM) in 1976 and has been a world-class center of exhibits and education ever since.

***

Mulberry Harbors and Museum, Arromanches, France

The tiny French coastal town of Arromanches, perched on the sands of Normandy, holds another of my favorite war sites. Not far from the immaculate rows of gleaming marble headstones of the US cemetery at Omaha Beach, the beach village had its fate permanently altered when it was chosen to be the main port of the Allies.

One of the most vexing logistical challenges for D-Day planners was the issue of transferring the move millions of pounds of Allied soldiers, vehicles, weapons, and supplies from ship to shore once the troops had established a beachhead. At Churchill’s order, engineers were set to the monumental task of constructing giant ports nicknamed “Mulberry Harbors”, designed to accomplish the feat.

Remains of Mulberry Harbor, Arromanches, Normandy

Before the blood had washed away from the Normandy sand, the ports were unloaded from ships and attached by brave engineers under enemy fire. While bullets still flew the ports were operational and offloading tons of materiel per hour for the final push against Hitler’s Riech.

Today, a very well done museum perches above the coast and describes the incredible engineering task undertaken to build the ports. It gives even a layman like me a good idea of how this was pulled off, and of the massive challenges (storms, waves, German gunfire) that the Mulberry builders had to contend with.

Remains of Mulberry Harbor, Arromanches, Normandy

But this isn’t the most moving part of the area; the really evocative sights are sitting just off the coast and demand no entrance fee. Still visible in the surf are the ghostly hulks of the prefabricated ports themselves. The skeletal iron beasts, now rusted and worn away by decades of tide and salt water, serve as a silent reminder of the world-changing event that came to Normandy’s shores. And they remind us of the ordinary people—most now passed away—who found themselves swept up in the gale force of history.

Original article can be found here: Veterans Day and Historic Military Sites

Rolf Potts's Blog

- Rolf Potts's profile

- 323 followers