Sumiko Saulson's Blog, page 20

July 14, 2018

Basement Beauty by Carmilla Voiez (Excerpt)

[image error]Carmilla Voiez is a proudly bisexual and mildly autistic introvert who finds writing much easier than verbal communication. A life long Goth, Carmilla lives with a daughter, two cats and a poet by the sea. She is passionate about horror, the alt scene, intersectional feminism, art, nature and animals. When not writing, she gets paid to hang out in a stately home and entertain tourists.

FIND OUT MORE AT – www.carmillavoiez.com

TWITTER – https://twitter.com/CarmillaVoiez

GOODREADS – https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/4893389.Carmilla_Voiez

FACEBOOK – https://www.facebook.com/Author.Carmilla.Voiez

Excerpt from Basement Beauty (in Broken Mirror)

![Broken Mirror and Other Morbid Tales by [Voiez, Carmilla]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1531680049i/25978698.jpg) ‘You’re too beautiful to be killed, Tay,’ Lynsey assured her, brushing a manicured hand through freshly lightened hair.

‘You’re too beautiful to be killed, Tay,’ Lynsey assured her, brushing a manicured hand through freshly lightened hair.

‘What the fuck do you mean?’ Amalthea shook her head, jostling afro curls and revealing a petulant frown that drew her plump cheeks inwards.

‘Aint you heard? All the victims were ugly. Aint gonna happen to you, kiddo.’

Amalthea gazed at the empty pint glass in her hands. ‘Ugly?’

‘Yeah, not grotesque freaks or anything, just plain ugly: big noses, crooked teeth, greasy hair, you know. When I went to the dentist this morning they told me everyone and their f’in dog’s booked in for cosmetic work.’

‘Isn’t that odd?’ Amalthea rotated the glass this way and that between caramel fingers.

Lynsey shrugged. ‘Dunno.’

‘I think it’s odd.’

‘Whatever, girl. Just stop stressing, okay. You’re too beautiful to die.’

Amalthea glanced over the bar at the almost empty nightclub. ‘Seems quiet tonight.’

‘Yeah, well it’s still early. Heard there’s a gig on. Lots of people probably there. They’ll lurch in here eventually.’ Lynsey wiped down the dark wood counter with a damp, blue cloth.

‘Hope so. Drags when it’s this quiet.’ Amalthea placed the clean glass on a shelf at knee level. ‘Makes me want to open a book.’

Lynsey nodded. ‘Why don’t you? Hey, you alright for a minute if I pop out for a ciggie?’

Amalthea nodded toward the dimly lit room and grimaced. ‘Uh yeah. I think I can manage these three alone.’

‘Cheers, babes.’ Lynsey kissed Amalthea’s cheek and exited through a door between rows of optics.

Amalthea dried another glass from the crate and set it on the shelf. She repeated the action until the crate was empty without being disturbed by customers. When she looked up again she noticed a young man had entered the club and was strolling towards her. She recognised him from poetry nights. As always, he arrived alone. This evening he carried a slender book. She tried to see the cover, but it was angled away from her.

‘Hi,’ she said as he sat on a stool.

He smiled warmly. He was pretty, for a white boy. His skin seemed to have the soft glow of health that was rare in young men from this Scottish city. He reminded Amalthea of the father she hadn’t seen in over a decade, except this lad was even paler and his eyes resembled emeralds held in front of a flame.

‘Coffee, please.’

Amalthea nodded. She had never known him to order alcohol. Most of the patrons were ardent drinkers and this boy… man stood out for his lack of inebriation. Was he was still too young to drink or was he a recovering alcoholic? Would he frequent a club if he had a drinking problem? It was more likely that he simply found other ways to relax – those words clutched in his hand or the ones in his head? He fascinated her, although she wasn’t sure why. Physically, sexually, he wasn’t her type at all, but there was something about his gentle calm that attracted her and what better time to strike up a conversation than a quiet night like this?

She switched on the coffee machine and poured in freshly ground beans.

‘Seems quiet,’ he said.

‘Very,’ she answered. ‘What brings you here tonight? I normally just see you on poetry nights.’

‘You notice?’ he asked and his eyes gleamed brighter.

She stepped back and swallowed. Not another one? This club was full of would-be creeps and admirers. It was often hard to tell the difference between the two from this side of the bar. She hastily backtracked. ‘Sure. I know all my regulars. Do you write poetry?’

‘I’m not sure it’s any good.’

‘Ahhh, you should perform a piece here one night. It’s a friendly crowd. They won’t bite.’

He laughed. ‘Yeah, maybe. It could be fun to perform for… everyone, I guess. Do you write?’

‘Prose,’ she answered. ‘Nothing published. What book is that?’

‘Not mine. I’ve not been published either. A bit of Plath.’ He flashed the cover at her.

‘You like Sylvia Plath?’

‘I guess I have a thing for desperate sorrow.’ His face flushed and he suddenly appeared vulnerable.

She nodded, warming to him again. ‘There’s a lot of that in this town.’

‘I’m Daniel.’ He extended his exquisitely manicured right hand towards her.

Her hand met his half way across the bar. Her chewed fingernails, chipped purple polish and brown skin made an interesting contrast, worker versus what – public school boy, intellectual, rich kid? He seemed so different to her and yet the same. It confused her. It always did when she met people from such different backgrounds with a shared love of words. ‘Amalthea,’ she said. ‘Or Tay.’

‘Delighted to make your acquaintance, Amalthea. Do you work here every night?’

‘Almost.’

The machine’s noise altered as the dripping coffee filled a cream-coloured mug. She passed Daniel a black coffee with no sugar – his usual order.

‘Thank you.’ He nodded and took a sip. ‘And what do you do when you aren’t here?’

‘Sleep, write, oh and I’m studying English at the Uni.’

‘Busy…’ He seemed pensive for a moment. He teetered on the edge of something. Whatever it was, he decided not to ask. Instead he stood up and picked up his mug. ‘Thank you, Taya,’ he said and walked to a leather chair below a green spotlight.

Lynsey bustled back through the door, dragging cold air and the stench of tobacco with her. ‘Did I miss anything?’

‘Not much. I put the glasses away and we have a new customer.’

Lynsey stared across at Daniel and exhaled. ‘Seen him before, a bit of an odd ball, quiet, always alone.’

Amalthea nodded. ‘Maybe that’s the way he likes it.’

Amalthea stood outside the unlit entrance to The Pit and breathed in the cool, pre-dawn air. One hand brushed wild curls from her mouth and tucked them behind her ear. They sprang back across her cheek immediately, untameable.

As her skin acclimatised she drew jacket sleeves over her arms. A movement at the edge of her vision attracted her attention and she peered towards the shadowy alley where the night club bins were stored. Her direct gaze didn’t reveal any ghoul, goblin, animal or person skulking in the darkness, watching and waiting for her to leave, but her mind created a sinister shape anyway. For the past six weeks the evening news had continually reported unnatural deaths city-wide. Rumours of a modern day Jack the Ripper were rife. Now every alleyway had become hostile territory and every shadow a killer, preparing to strike.

With her meditative moments, of simply being, stolen by fear of the impenetrable darkness, Amalthea decided to button her coat and get moving. Home wasn’t far away, a mere ten minute walk and at four in the morning most of the drunks were already home, sleeping it off, or standing, unsteadily in taxi queues, waiting for chariots to return them safely to their beds. That was one thing to be said about fear of what might lurk the dark – it was good for the economy.

Gentle but pervasive drizzle vainly attempted to flatten her hair. Street lights mutated into dancing constellations and pavements were dotted with quicksilver puddles. Amalthea’s boots leaked and the liquid made her toes squelch. Sucking and dripping sounds masked the noise of her footsteps and the perfectly matched slapping of shoe leather behind her. Of course, when she glanced back, the street was empty, but the moment she faced forwards she felt his presence behind her, as always, matching her stride. He was the shadow from which she fled, unseen but perceived through all her other senses, making her hairline tingle – the man who wasn’t there.

She had tried to tell Lynsey of this consuming fear, but her friend hadn’t understood, dismissing her fears as paranoia. She decided in the future to only mention this deep, primal knowledge to her diary and wondered for one terrifying moment whether his other victims had known they were being hunted, but had kept silent or were disbelieved until the moment their vacated shells were discovered. She considered why she had dogmatically given this disembodied threat a male gender then shook her head. It was perfectly natural; serial killers were almost always male, weren’t they? The one who kills me will probably be male too, she reasoned.

Her scalp itched. Realising the utter pointlessness of another backwards glance, she balled her fists and marched onwards. Just five more minutes and she could lock the darkness outside, for what that was worth.

A shriek broke through the pittering-pattering shroud of raindrops. It echoed between tall Victorian town houses, converted into flats and bedsits – a cat or a baby waking from a nightmare? She waited for a repeat of the noise until she became aware that she had stopped moving and was standing as still as a statue as the rain continued to fall around and upon her. The sound didn’t return. Shivering, she willed her right foot to make its journey, one step forwards and asked her hip to tilt and her knee to bend. Movement didn’t follow her commands so she concentrated on her left foot instead – still nothing. Swallowing hard, she wiggled the toes of her left foot. Water moved between skin and cotton; the sensation made her nauseous.

‘Just walk, Tay,’ she whispered.

Rain hissed in her ears. Beneath her chin a waterfall tumbled onto her chest.

‘Just walk… five minutes!’

Ahead of her a tree that overhung the path shook water from its leaves like a huge dog. Large drops splattered as they hit the ground. What waited beyond that tree, hidden behind the trunk? She considered taking a longer route home where the streets were less shadowy and the traffic more regular.

Shivering from cold and fear, she watched as the heavy branches bent and purged until the urge to vomit returned. One hand stretched out to a rough red-brick wall beside her, knees bent and hips angled yet her feet remained bolted to the spot.

How many had been killed already this year – ten, no twelve, would she be the thirteenth? She shook her head; this fear was not rational. She wasn’t being hunted and her home was a mere five minute walk from this spot. Five minutes… she could walk for five minutes. Five minutes… no distance at all, yet one step forwards felt beyond her reach.

‘Tay, get a grip!’ Her mind used her mother’s voice, dominant, matriarchal and full of a rich, musical patois. She nodded, fighting her foolishness and the paralysing fear of what – a tree, a shadow and a lone shriek? What set her off this time? ‘You is fierce, a powerful woman. This shit is beneath you, Amalthea. You shame me.’

Amalthea pushed against the wall, straightening her hips and knees. Raising her head, she blinked diamonds from her eyes. The raindrops altered their route and formed puddles within the cradles of her earlobes. With Herculean effort, she stepped forward. Once freed from their traps her legs adopted their natural rhythm. Swift and sure she passed beneath the branches as a single sphere fell and trickled between her neck and jacket collar. In less than five minutes she reached home, pushing bolts into place and turning keys in locks.

The breath she took filled her lungs with warm, dry air. She gulped it down as though it was her first breath then headed for the bathroom and a towel.

July 6, 2018

Writing Horror While Trying to Avoid Stereotypes

[image error]Carmilla Voiez is a proudly bisexual and mildly autistic introvert who finds writing much easier than verbal communication. A life long Goth, Carmilla lives with a daughter, two cats and a poet by the sea. She is passionate about horror, the alt scene, intersectional feminism, art, nature and animals. When not writing, she gets paid to hang out in a stately home and entertain tourists.

FIND OUT MORE AT – www.carmillavoiez.com

TWITTER – https://twitter.com/CarmillaVoiez

GOODREADS – https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/4893389.Carmilla_Voiez

FACEBOOK – https://www.facebook.com/Author.Carmilla.Voiez

Writing Horror While Trying to Avoid Stereotypes

It’s not as easy as it sounds. While tropes, cliches and stereotypes might be easy to spot in others work, they can become embedded in our psyches and spill out into the stories we tell.

While preparing for a panel discussion on the subject I realised how many tropes I’d inadvertently included in my own work, including the dreaded demonic pregnancy trope.

Cliches and tropes are common in all sorts of genres. They are familiar signposts in a story due to our shared cultural exposure to them, but at the same time they are frustrating and limiting. I love it when tropes are inverted, and you get that aha moment. There are so many gender stereotypes, particularly in horror – the aforementioned demonic pregnancy, the violent psychopathic male with mommy issues, the possessive mother, the jealous stepmother, the abusive father and/or stepfather. The femme fatale cliché, oh but those women can be so damn sexy. Cliches don’t appear out of thin air. They are overused themes and characters and can make writing predictable. I suspect their frequent use is in part why genres like horror rarely get serious recognition within literary circles.

[image error]

So cliches tell us what to expect.

Like the one about the heroine finding her strength after being violently raped. I hate that one. The pornification of torture worries me, both in and outside the horror genre. It can cross into erotica and that is pretty dangerous when you consider the real world’s penchant for violence against women. There are other types of women in horror too: the princess in the tower, the trophy to be won, and they are all tropes that bleed out into the real world, both in male and female imaginations, fetishizing feminine weakness and making it seem somehow precious. However, women were being tortured and killed for kicks before the horror genre, so an argument can be made that it’s simply reflecting society. Either way I don’t like it. It turns me off stories quicker than anything else.

Cliches help writers by providing template characters.

I’m a member of a number of writers groups on social media and it is surprising how many male writers are afraid of writing female characters. I like Gustave Flaubert’s argument that when he wrote Madame Bovary he was simply writing himself. We are far more similar, men and women, than we are different in our essential beings. It is only our outside experience of the world that seems at odds. It might seem strange that men feel this fear of writing women, when female writers frequently write men. However a quick look at the stories we all grow up reading and watching shows that male is the default, as is white, in almost all our entertainment and certainly in books. Darren Chetty wrote a piece that was included in “The Good Immigrant” called ‘You can’t say that! Stories have to be about white people’, about his experience teaching ethnically diverse students in East London. In summary when these children wrote stories they always had white characters with English names, because that was what they had read.

Gender as plot.

[image error]

There are so many horror tropes surrounding female characters that it is hard to navigate at times. Your typical horror villain is a white man with mommy issues, and your typical victims are attractive young women, frequently used as sexualized fodder or there to be saved by the male hero. This isn’t all horror is, of course, but it is what many of us think of, especially when we aren’t working in supernatural horror where we do find more super-powered women.

When we are dealing with a slasher or serial killer story the last victim standing is termed the Final Girl. There women are rarely characterized beyond their ability to survive, meaning that they fall neatly into the stereotype of victim. Even a victim who survives is still a victim. They can also stand as a warning to would-be male aggressors that some kittens have claws, but even in that role they are often sexualized because of their aggression in a sub/dom kickass survivor way. There’s a racial element to the Final Girl as well. I can’t think of a Final Girl who’s a woman of color. And lest we forget the moral, Final Girls are pure, virginal and good, even if they aren’t technically virgins their innocence is part of the drama. When the final girl is well drawn she can be empowering, but, as happens more often than not, when she is simply a plot device it is frustrating.

How do we avoid cliches?

As I said at the start it is easier said than done, but if we draw our characters fully rather than rely on stereotypes we’re at least part way there. For the panel discussions we looked at some of our own characters and to what extent the fell into or avoided gender stereotypes. I chose four characters from The Starblood Trilogy.

Star, my female protagonist, is hero and victim simultaneously. She is victimized because she has lost her sense of self – something that was happening to me at the time. She is easily manipulated, but her inner strength does win out. I guess you could classify her as a Final Girl (although she isn’t the last one standing). She seems annoyingly passive at times, drifting through the story, but when she realizes her own strength, ironically through torture, she does become powerful and eventually can save herself.

Star, my female protagonist, is hero and victim simultaneously. She is victimized because she has lost her sense of self – something that was happening to me at the time. She is easily manipulated, but her inner strength does win out. I guess you could classify her as a Final Girl (although she isn’t the last one standing). She seems annoyingly passive at times, drifting through the story, but when she realizes her own strength, ironically through torture, she does become powerful and eventually can save herself.

Satori, my male protagonist, is in part hapless hero and in part anti-hero. Like Star, he develops throughout the book and becomes gradually less self-involved. He is the reason bad things happen to him and his friends, even if he is the one that fights against evil and tries to save Star. I wrote him this way because he is unaware of his impact on the world. He comes from a position of privilege, although he isn’t what you’d call an alpha male, and in fact is the victim of male violence in the books. He’s my self-defined good guy. He sees Star as a human being, but at the same time resents her for leaving him.

Lilith, my female antagonist, is definitely a villain, although some readers have claimed she’s a feminist hero. She is a survivor of assault, there we go again, but her extreme strength and power have warped her perspective of fairness and cruelty. While her end goal is not evil, her acts certainly are. Lilith frequently inverts the sexual stereotypes, but can do so because she is a supernatural creature.

Freya, is a vital support character. She is a villain, but often sympathetic. Without Freya none of the strands of the story would come together. She works against Satori and with Lilith. She too is a victim of the terrible events of her childhood, but it does not excuse her actions. She is the most messed up and powerful character in the trilogy, and I love her for it. Unlike Star, she is the Final Girl, and I’m tempted to continue her story beyond the trilogy. She provides a strong, human, female character who works behind the scenes and is all the more effective for sticking to the shadows. There is nothing that can be taken from her that will cause her to fall apart. She’s like a force of nature. She’s what happens when we’ve already hit rock bottom and there’s no where left to fall. I think if anything, Freya is the one who manages to avoid the gender stereotypes.

[i] The Good Immigrant, ed. Nikesh Shukla, published by Unbound, London, 2016

The top photo is of the author. The middle two photos are Alora Mishell Wolf her Instagram is @aloralaura

July 3, 2018

Interview with V.H. Galloway, author of

[image error]V.H. Galloway is a novelist of Science Fiction and Fantasy and graduate of the Viable Paradise Workshop. Born in the Ft. Greene section of Brooklyn, N.Y., she has become a bit of a rolling stone. A resident of Austin, TX, she has also lived in Ohio, California, and Nevada. She is still in search of a place to call home.

Buy links:

Book 1 – The Un-United States of Z – https://amzn.to/2sDFrP5

Book 2: The Rotting Road – https://amzn.to/2szTo0A

Book 3: The Refugee Prophet – https://amzn.to/2M4CEq8

Book Description:

[image error]In a near-future Los Angeles, Dr. Zen Marley is torn between two conflicting realities: his buried southern roots and his preppy west coast professor persona. He must travel home to face the reality of his mother’s failing mental health. But he finds an aberration: a monstrous impostor wearing the rotted shell of his mother’s skin. In a twisted case of self-defense, he kills her, but not before he is also infected.

With his humanity eroding, Zen sets off on a cross-country quest through a racially divided America to rescue his sister, find a cure, and stop the advance of the sentient flesh-eating army led by his highly intelligent, but psychotic former student. This is the first installment of The Un-United States of Z trilogy.

Interview:

Q. What inspired you to create Dr. Zen Marley as a character.

A. I share just a couple things in common with Zen as a character. I’ve lived on the West Coast and have family in South Carolina – spent quite a bit of time there under the watchful eyes of my grandmother, aunts, uncles and extended family. And over time, it became increasingly difficult to make the long trek back for visits – something I regret. Though that aspect of my life is the bud from which Zen bloomed, that, as they say, is where the similarities end. Disillusionment and his mother’s illness have caused Zen to turn away from home, from his roots.

Q. Dr. Zen Marley has southern roots and travels back home; how much does the Southern Gothic horror genre inform his experience and genre?

A. Zen tries, I mean, tries really hard to cover his southern roots. But as anyone born in the south or who spends significant time there knows, his attempts prove futile. It’s in his blood. And this becomes more evident once he lands in South Carolina and during the ensuing trip through the south. On his own and through periodic tongue lashing reminders from his sister, Zen comes to appreciate and embrace his southern upbringing and that foundation of strength. The zombies (rotters), presented with a significant twist, also stem from Southern Gothic hoodoo tropes.

Q. The Southern Gothic horror convention often touches upon ghosts of the dark legacy of the south, such as Jim Crow, segregation, the Mann Act and slavery. Does your story do so at all?

A. Absolutely. This story poses a question – What would America do if we really turned out to be the monsters they envision? And without giving too much away, Zen learns that America in many ways is as divided as it was during that not-so-distant time in our history. And that it only takes something small to re-ignite those old flames.

Q. I am from Los Angeles – how much is it in the story, and how does Dr. Zen Marley’s experience there differ from the South?

A. The first book of the trilogy begins in the South Carolina. Book 2 – The Rotting Road, takes Zen and his companions on a road trip through much of the southern U.S. The final book of the trilogy – The Refugee Prophet – is centered in Los Angeles. This is where it all goes down. Zen takes on his foe – his former student, Idriss who has a vision that puts Black people at the top of the new food chain. By then, America is largely apocalyptic. Los Angeles is the place where Zen has built his post-southern life and combined with his reaffirmation of the importance of the past, being back helps set him on more firm footing. This bolsters his confidence for the battle that is to come.

Q. A lot of people are up in arms about the current political situation, and I have read that zombie stories become very popular during Republican presidencies because of our fears about conformity – whereas Democrats inspire vampire stories due to the fear of licentious behavior and sexual perversion. Do you think there is any truth to this?

A. Fascinating! While I’d love to dive into the data supporting this, I can say that throughout history, we have examples of how real life impacts art. So, for me, it’s a given that the current socio-political climate can inform art.

Q. If so, do you think any of the tropes or images in your story relate to the current political situation, and how?

A. The Un-United States of Z was actually written prior to the most recent election. Still, it’s a story about zombies – black zombies, at that. And these aren’t your run-of-the-mill flesh eaters, they’re sentient, angry, and determined to right some wrongs of the past. If that doesn’t relate to the current political climate, I don’t know what does.

Q. How do you feel about writing horror as a woman? Does it pose any specific challenges?

A. To even debate the challenges that a woman horror writer faces is folly. It’s a given, not something to ponder. There are folks that simply only want stories by and about people who remind them of themselves, luckily, I’m not one of them. A good book goes a long way toward breaking down those barriers. I, in turn, must focus have laser-focus on the things that I can control. That means: improving my craft, reading widely from other authors I admire, and supporting/helping other writers.

Q. Do you feel you have faced any exceptional challenges as a black horror writer, and how has it informed your views as a writer?

A. Some call it two strikes, I call it two assets. Writing from the perspective of a black woman gives me an opportunity to introduce others to a fairly unfamiliar voice. My job is to write well and to continue to grow. As much as we’d like to, we can’t control the readers.

Q. What do you have on the drawing board that our readers can expect to see from you next?

A. A good writer is always thinking about the next project. I am currently shopping a fantasy novel with agents. Also on tap are several short stories in various stages of completion and a new novel set in New Orleans, a horror-fantasy mashup.

July 1, 2018

Lisa Macon Wood on Women in Horror Fiction

[image error]

L. Marie Wood is the bestselling author of 2 novels and over 125 short stories. She has been published in print and online and has won several awards for her short fiction. Her 2017 short story, “The Ever After” was part of the Bram Stoker Award Finalist anthology Sycorax’s Daughters. L. Marie Wood has been recognized in The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror, Vol. 15 and is one of the authors chronicled in the100+ Black Women in Horror Fiction collection (2018).

Introduction

Horror fiction, in and of itself, has never been regarded as an accepted genre by literary fiction enthusiasts. The content offends more practical sensibilities, the fantastical aspect to which the reader must adapt to enjoy work in this genre require many allowances. Authors in the genre have never wholly been taken seriously, and over the centuries, only a few stand out in memory. These authors, namely Edgar Allan Poe, H. P. Lovecraft, Stephen King, brought fresh ideas to the table; they made people look at horror in a new light. Stephen King, above all, brought commercial validity to a genre that had previously been regarded as pulp, influencing writers in other genres to incorporate the supernatural in their prose. As such, Stephen King is synonymous with horror and is, more often than not, the only horror author that mainstream readers can name. Largely, other authors in the horror genre go unread by the mainstream community, if they are recognized at all.

Some names are resurrected under the guise of the classics – Mary Shelley and Bram Stoker most notably. The recycling of horror movie themes helps in that vein, allowing literalists to indulge in reading the original text upon which the screenplay was based. But the group that makes up the intricate blanket of horror goes unseen. The likes of Richard Matheson, Ray Bradbury, Clive Barker, and the lesser known Robert McCammon, Douglas Clegg, and Joe Lansdale remain important to a subset of society (the horror community) but register a mere blip on the screen for most readers, if at all. Female authors suffer a worse fate. They remain unknown, in large part, to mainstream readership as well to the horror community. While a small few break out and gain notoriety for a time (Anne Rice, Tananarive Due, L. A. Banks), many write in relative obscurity (Kathe Koje, Tina Jens).

Throughout history, women have played the role of victim in horror stories written by male and female authors alike. A comfortable alcove to place female characters, writers became used to the power struggle between good and evil with a woman in the middle as the coveted prize. Rafferty stated, “…a woman’s place in horror has been pretty well defined: she’s the victim, seen occasionally and heard only when she screams” (2008, ¶ 2).

In the early 1800s, a new style of fiction aptly termed gothic horror due, in part, to the dark settings used in its prose, was written by women for women, unseating the ‘woman as victim’ trope for willing readers. Crafty escapes from diabolical antagonists were offered to women who craved an exciting read. As Leslie stated, “Most of these writers were women and the intended audience was also female, with many novels appearing serialized in ladies’ magazines

Many trace the lack of female authors represented in the horror genre to a catchall sub-genre called paranormal romance. Paranormal romance is unique within the horror genre in that its purpose is not, “…to evoke terror, but to present an impossibly romantic alternative to reality,” (Kelleher, 2008, ¶ 2). As such, this sub-genre straddles the line, belonging to both horror and romance, producing an unlikely tug of war.

Horror has been accused of sexism in the past, and with the relative exemption of female horror authors who write prose with the genre’s original intention in mind, this accusation is likely to reoccur in the future. As Rafferty indicated, “[Many female authors] don’t appear to be concerned, as true horror should be, with actually frightening the reader,” (2008, ¶ 4). Does that assertion explain the disdain with which paranormal romance is regarded? Much has been made of the nature of the sub-genre, which focuses more on supernatural romance and relationships than the horrific. The material therein straddles the line between quiet horror and romance, the aspect designed to frighten the reader downplayed or rendered impotent. For example, the vampires in Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight series are passionate and loyal, only revealing their true nature when defending a particular human or each other. The books marginalize traditional vampire characteristics, such as the need to feed (and the brutal aspects of this practice), and their status as undead (the characteristics and emotions the vampires display are alarming lifelike). While creative license is an unwritten rule in fiction when utilizing an archetype, Twilight’s vampires are so different from historic and even recent depictions that fans of traditional horror prose find the books difficult to accept. Are female authors in the paranormal romance sub-genre considered horror authors at all? The demographic it appeals to – teenage girls – suggest that they are not.

Over the years, as paranormal romance has gained steam, female horror authors of every sub-genre have been shuttled into that box. Indeed, as Barnett of The Guardian stated, “The assumption is that a woman writing in the horror genre will be writing paranormal romance,” (2009, ¶ 6). But there are many women writing other forms of horror: Sarah Langan in psychological horror and Lisa Tuttle in splatter punk, to name a few.

Over the years, as paranormal romance has gained steam, female horror authors of every sub-genre have been shuttled into that box. Indeed, as Barnett of The Guardian stated, “The assumption is that a woman writing in the horror genre will be writing paranormal romance,” (2009, ¶ 6). But there are many women writing other forms of horror: Sarah Langan in psychological horror and Lisa Tuttle in splatter punk, to name a few.

But is there more that affects how female authors are received than their being categorized in a cross sub-genre?

An opposing argument could be made. In a later article, Barnett suggested that, “Allegations of sexism are perhaps unfounded when leveled at the industry itself: the sheer numbers of women working not only as authors but also in the film industry and in publishing… …suggest there is no glass ceiling on the creative side,” (2010, ¶ 8). With the heightened acceptance of women in all societal roles, including industrial and military, the fact that many women are involved in the craft – writing, editing, teaching – is a feather in the proverbial cap. However, is that a product of the times? Does the need for bloggers, reviewers, and professionals in the field boost the number of women involved by necessity? Does the sheer number of women in the world compared to men – 57 million more as reported in 2010 – (United Nations, 2013, ¶ 3) make it inevitable that more women would be working in the field?

If history has anything to do with the situation women find themselves in presently, one would not be surprised. Across the literary genres, published authors are (and have always been) predominately male. According to Crossref-it.info,“ In the ancient world literacy was severely limited, and the majority of those who could write were male,” (2013, ¶ 1).

There is a theory in circulation that women have been marginalized as authors because of original sin. Eve, regarded as the reason for original sin, in essence, created the playing field for women to be treated differently. Hence male dominance seems natural because the female is somehow not to be trusted with the task. What behaviors are being expressed to boys that cause this mindset to resonate across time, subconsciously if not consciously?

References to the lesser status of women are all around. They can be found in the Bible, in ancient texts, and in literature. Women have historically been considered sexual beings and when sexuality was taboo, so were women. Many cultures maintain that a distance be between male and female; their relationships are structured so that the women are subservient to men. As went life, so went literature. Female characters were periphery – as likely to be left out of a piece as not. While this trend gradually changed over time, it was slow going. From silent, milling bystanders, women became important to the storyline because of how the men in the tale reacted. “… [T]he novel depicted women as viewed by men, and the typical heroines were either paragons of virtue or of vice,” (2013, ¶ 26). It wasn’t until the eighteenth century that women created work that made society take exceptional notice. The horror genre saw the likes of Ann Radcliffe change the way that women were viewed in horror fiction: her propensity toward advocating women’s rights in her work creating a form of reform through osmosis. She joined a handful of women (notably Jane Austen) who changed the face of fiction. Did those changes make an impact on how female horror authors are regarded in present day?

The questions posed in this section lead to the supposition that while women are viewed differently in this century than in times past, gender still plays a part in how their literary work is accepted. This is shown in published statistics, industry surveys, and a questionnaire conducted as research for this paper. Respectively, women continue to write and excel in their field, however their work is not reviewed as often as males. Per The Guardian, at The New York Times Review of Books, of the number of authors reviewed, “… 83% are men (306 compared to 59 women and 306 men), and the same statistic is true of reviewers (200 men, 39 women),” (2011, ¶ 5). A survey conducted by VIDA Women in Literature reveals that female authors make less than male authors in the same genres. Ten people (five women and five men) were surveyed as part of the research for this paper. They were asked two questions, one of which was to name three authors. Some struggled with naming three, but of the three male respondents who met the criteria, only one named at least one female author.

A popular argument exists to explain the issue hand. It states that female authors are not writing in genres that appeal overwhelmingly to men, therefore, men are not buying it. As Cruz aptly pondered, “As women, are we pigeon-holing female authors and creating subgroups for them, stunting their growth as writers?” (2013, ¶ 5). The final question of the research questionnaire asked ten people to name the genre they enjoyed reading most. Romance topped the list (3 of 10 responses). Science fiction and mystery made the list as well, among other genres. There was no consensus on genre among the male respondents whereas 60% of the female respondents chose romance. None of the ten respondents chose horror as their genre of choice. These results are further legitimized by the assertion made by Penny Sansevieri as quoted by Cruz, “I really think the problem is that men are in stronger categories generally—thrillers, mystery, political thrillers, horror, suspense, etc.,” (2013, ¶ 4). These results bring another question to the forefront. If the statistics gathered by the National Endowment for the Arts report are correct, women buy and read more books than men (Table 21, p. 23). That reality should serve as a boon to genres within which female authors are predominately read, negating the subgroups created by individual interest and elevating their status in mainstream consumer markets. Why is this not occurring?

Is there a double standard? Can men and women of equal talent and similar style write about the same subject matter and be reviewed and, subsequently, received differently? The propensity for women to assume male pennames when they write in so-called stronger categories/genres begs the question. Are women relegated, in large part, to what has been termed chit lit or beach books (lighter material designed for fanciful escapism) if they are to be successful? Either that, or mask their work as that of a male? Finally, for the female author, is the horror genre too commercially unrewarding to claim? Many female authors who have written horror fiction merely dabble in it, coming to visit for a time, then moving on to greener pastures. Mary Shelley did the same as many contemporary female authors, offering a fantastic piece of work in Frankenstein and moving on to write in other genres. Gender appears to be a defining factor in the success of the female author.

Perhaps men push harder. In the mid to late 1970s, horror fiction made a surge. Authors found success in their released novel and, shortly thereafter, the film adaptation. A newcomer named Stephen King produced a different kind of horror fiction – one that was as believable as an anecdote told at a family gathering. His work resonated with people, scaring them deeper than they expected and keeping them wanting more. Many authors felt they could replicate his style and saturated the market with formulaic, predictable volumes. In the figurative shoving match for leverage, perhaps men gained an advantage.

There is a final reason for the marginalizing of female authors in the horror genre, and this, perhaps is the most disturbing: the perception that women just can’t do it. Does society think that males write horror fiction better than women? Do they believe that women are too fragile to imagine unsettling horrors? If dark thoughts lurk in a woman’s mind, is it somehow improper (unladylike?) for them to be entertained and transposed onto a page for all to read? Is this mindset a socialized gender bias? Perhaps there is some merit to the latter. Miller states that, “Conventional wisdom among professionals in the children’s book business is that while girls will read books about either boys or girls, boys only want to read about boys,” (2011 ¶ 8). Children often take on the characteristics of their parents and respond to what they see. While there is a place for inherent proclivity, much of early learning is parroting. If parents are buying books that are considered gender appropriate (based on societal rules for male and female behavior), children will gravitate to them naturally when they begin to make their own selections. As children age, their interests may change, but the notions of male and female behavior have solidified. Hence the interminable cycle.

An interesting connection exists: those who are more interested in reading literature written by a male were, more than likely, taught by a woman. According to Anderson, “A 2006 study by the National Education Association showed that preschool and elementary school children are taught by 75 percent more female than male teachers,” (2013, ¶ 1). This trend, albeit with fluctuating percentages, has always existed. Students are more likely to be taught by women in all disciplines and at all grade levels. Is it more acceptable to learn how to write from a woman than to read a woman’s work? The answer to that question lies in many practices and mindsets that persevere in history and to date in not only gender, but also racial and cultural settings.

Women continue to write and publish around the world. While the US and UK produce most of the commercial horror fiction, female authors are influenced by the genre globally. Horror fiction is experiencing a lull in written form and an uptick in visual media as adaptations from past novels are created for movies and television, but that has not stopped the likes of Sara Pinborough and Helen Oyeyemi from producing stellar work in the genre. The horror genre itself is ailing – the change in layout at major bookstores reveals that truth. Horror is lumped in with Thriller, Mystery, and Suspense in some locales, and in other bookstores, the heading of Fiction covers all genres outside of the nonfiction bucket. This reduces the chance that a horror book by a new author might be selected if not deliberately sought out; layouts such as these require readers to know the name of the author they are looking for, as does online shopping.

While we watch the changing of an era, as bookstores close their doors in favor of online storefronts, one can’t help but wonder about the future of the horror genre and, by extension, the fate of the female horror author. Online presence provides for a wider audience with cheap prices and instant gratification in the form of a download, so perhaps, as demographic marketing of horror advances, more people will be willing to try horror written by women. The Internet may prove to be the venue where the playing field is leveled and gender is no longer a factor.

Bibliography

Anderson, J. A. (2013). Male versus female teachers. eHow.

http://www.ehow.com/about_5623553_male-versus-female-teachers.html

Barnett, D. (23 September 2009). Sexism in horror novels: the real monsters aren’t the ones you

think. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2009/sep/23/sexism-horror-novels-row?guni=Article:in%20body%20link

Barnett, D. (24 February 2010). The spectre of sexism haunting horror fiction. The Guardian.

http://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2010/feb/24/sexism-horror-fiction

Cruz, K. (30 April 2013). Read all about it! Female authors still get less press. Levo League.

http://www.levoleague.com/articles/news/female-authors-still-get-less-press-than-men

Kelleher, K. (27 October 2008). The horror, the horror: Women writers provide empowering

portraits. Jezebel. http://jezebel.com/5069127/the-horror-the-horror-women-writers-provide-empowering-portraits

Leslie, V. H. (2013). Considering the legacy of women writers in horror fiction.

This is Horror. http://www.thisishorror.co.uk/columns/bloodlines/legacy-women-writers-horror-fiction/

Miller, L. (9 February 2011). Literature’s gender gap. Salon.

http://www.salon.com/2011/02/09/women_literary_publishing/singleton/

Portrayal of women in literature. 2013. Crossref-it.info.

http://www.crossref-it.info/articles/322/Portrayal-of-women-in-literature

Raffterty, T. (28 October 2013). Shelley’s daughters. The New York Times.

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/26/books/review/Rafferty-t.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1&

Reading at risk: A survey of literary reading in America. National Endowment for the Arts.

June 2004.

Research shows that male writers still dominate books world. (4 February 2011). The Guardian.

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/feb/04/research-male-writers-dominate-books-world

United Nations Statistics Division. The world’s women 2010: Trends and statistics. (2013).

United Nations. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/Worldswomen/Executive%20summary.htm

June 30, 2018

Carmilla Voiez on Vampires

[image error]Carmilla Voiez is a proudly bisexual and mildly autistic introvert who finds writing much easier than verbal communication. A life long Goth, Carmilla lives with a daughter, two cats and a poet by the sea. She is passionate about horror, the alt scene, intersectional feminism, art, nature and animals. When not writing, she gets paid to hang out in a stately home and entertain tourists.

FIND OUT MORE AT – www.carmillavoiez.com

TWITTER – https://twitter.com/CarmillaVoiez

GOODREADS – https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/4893389.Carmilla_Voiez

FACEBOOK – https://www.facebook.com/Author.Carmilla.Voiez

On Vampires

Vampires are both elusive and seductive. They look like us, but they are not us. They can be monstrous or they can be liberating. But the real attraction of the vampire genre for me and the reason I wrote Basement Beauty is how much these undead creatures say, historically and currently, about the world we inhabit and society. Vampires have been representing political tensions since the 1800s. The fears their lore reflects are as relevant today as they were over a century ago.

Vampires are both elusive and seductive. They look like us, but they are not us. They can be monstrous or they can be liberating. But the real attraction of the vampire genre for me and the reason I wrote Basement Beauty is how much these undead creatures say, historically and currently, about the world we inhabit and society. Vampires have been representing political tensions since the 1800s. The fears their lore reflects are as relevant today as they were over a century ago.

The Class-struggle: an aristocratic vampire feeds on peasants who inevitably rise up led by the middle-class hero (Van Helsing for example), to finally destroy the predator. This storyline could have been lifted from Marx or Stoker equally. Or the fear of immigration: Dracula comes to England from Romania, bringing terror and destruction, a narrative that British fascists UKIP are fond of repeating. Or the empowerment of women v the destruction of rational men: the female vampire, frequently portrayed as lesbian (as in J Sheridan LeFanu’s Carmilla), embodies a fear of female agency and female sexuality that is not controlled by men. The female vampire penetrates the male (or female) victim with her mouth, this vampiric sexual organ is both a soft, inviting hole and a phallus (penetrating and dangerous fangs), the ultimate vagina dentata. I doubt the emergence of lesbian separatism and the prodigious rise of the female vampire in cinema during the 1960s and 70s are unconnected. Movies empower the male viewer with the presence of the vampire hunter (Helsing) or the male narrator (in the Vampire Lovers) to help contain the genre within a box guarded by the rules of patriarchy. So whether class, immigration or feminism, the vampire is representative of the “other” in popular fiction, the one that is not us. A force that preys on us and that we feel both seduced and repelled by.

I am fascinated by the current shift of the fictional vampire from monster to romantic  hero/heroine. I suspect this is indicative to the shift of attitudes toward sex and sexuality in modern society. In Twilight, for example, the vampires’ humanity and vulnerability is part of their attraction. It is as though we have begun to defang these monsters.

hero/heroine. I suspect this is indicative to the shift of attitudes toward sex and sexuality in modern society. In Twilight, for example, the vampires’ humanity and vulnerability is part of their attraction. It is as though we have begun to defang these monsters.

All this is the background noise in front of which I wrote Basement Beauty (the novella featured in Broken Mirror and Other Morbid Tales). In my book the vampires believe they are a superior race and are separatists using humans only for food. One rogue vampire disobeys the clan and dares to mix with filthy human pigs. His behaviour is seen as a threat to the other vampires that must be destroyed. The fear and hatred could reflect homophobia or Nazi style racial purity. Weaved into this story of hatred and eugenics, is a human story. Heroes, not victims the two tales merge until, hopefully, the reader does not see any one as the other, but instead as individuals and forces to be reckoned with. The political struggles are personal struggles for survival rather than something abstract that cannot be understood.

Do you agree with my thoughts on the politics of the vampire? Do you have any other thoughts of your own as to why they are so important to our popular culture?

Do you find yourself siding with humans or vampires in films and books? Why?

Male writers tend to show vampires as outsiders while many modern female writers show them as lovers and partners? Why do you think this is?

My favorite vampire stories –

Dracula by Bram Stoker

Necroscope by Brian Lumley

Let the Right One In by John Ajvide Lindqvist

Photos by Angel Harkins

June 28, 2018

Interview with Dexter Williams, author of Enslavement

[image error]An award-winning screenwriter who has been writing screenplays for two decades. He has a huge love for the horror genre and has written five feature film scripts and four short film scripts. One of his feature film scripts, “Demon Crystal”, was recently optioned by Pulse Pounding Productions. Virtually all of his scripts have been recognized by major film festivals.

About Enslavement

“Enslavement” is a cross between “The Craft” and “Red Dragon”, and it’s a horror-thriller about a shy high school student who gets hypnotized by a dangerous Goth girl into performing bloody ritual sacrifices for her sinister goddess-worshiping cult. Four performances provided the inspiration for “Enslavement”: Fairuza Balk in “The Craft”, Kim Director in “Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2”, Sophia Bush in “Stay Alive”, and Dakota Fanning in “The Twilight Saga: New Moon”. It took me just two weeks to finish the script, and it recently was named an Official Selection in the Underground Indie Film Festival.

The Interview

Q. As a goth, I assure you I don’t perform bloody ritual sacrifices for my sinister goddess-worshiping cult. In fact, I am a Christian. Are there any positive portrayals of goths in your play?

A. The Goth girls are the antagonists in “Enslavement”, but it is in no way a put down of Goths in general. There are some Goths who do positive things in the community. I feel Goths have a unique fashion style that I find quite interesting and cool.

Q. What do you think of the hot/dangerous goth girl trope in general?

A. It is an interesting trope I wanted to explore in “Enslavement”. I think the trope in general is kind of cliché.

Q. How does your goth girl villain differ from those portrayals that inspired her?

A. The Goth girl villain in “Enslavement” is different in that she is an expert in hypnosis and mind manipulation. I don’t think there has been a portrayal like that I’ve seen in any feature film. She does hypnosis in a way that is different from the typical swinging watch thing.

Q. Do you think the bad girl villains are inspired, in general, by any sort of fear of women or womanhood in the patriarchal society. And does your treatment touch on that at all?

A. In no way were the villains in “Enslavement” inspired by any sort of fear of women. My treatment doesn’t touch on that at all.

Q. What other horror projects have you worked out?

A. In addition to “Enslavement”, I’ve also written the feature scripts “Mistresses of Sleep” and “Demon Crystal”. “Demon Crystal” was recently optioned by Pulse Pounding Productions, an up-and-coming production company specializing in genre fare (especially horror). I’ve also done the short film scripts “Curse of the Scorpion Ring”, “Fear the Clowns”, “The Hypnotic Trap”, and “Slave in the Spotlight”. I will soon be starting work on a short called “Zombie Killer”.

Q. Those sound exciting! Can you tell us more about your short film scripts, “Curse of the Scorpion Ring”, “Fear the Clowns”, “The Hypnotic Trap”, and “Slave in the Spotlight”?

A. “Curse of the Scorpion Ring” is about a young lady who “borrows” an ancient Egyptian ring from the local museum, and the horrible price she pays for it. This script was partly inspired by a scene from the film “Warlock” in which a character wore a Scorpio ring.

“Fear the Clowns” is about a lady who visits a hypnotherapist in an effort to discover the reason behind her recurring nightmares of being chased by sadistic clowns.

“The Hypnotic Trap” is about a teenage girl who gets hypnotized by a mysterious woman-in-black into staying at her house, and the terrible fate that awaits for the teen.

“Slave in the Spotlight” is about two best friends whose night-out-on-the-town takes a dark turn when they go to see an alluring hypnotist’s nightclub act.

“Fear the Clowns”, “The Hypnotic Trap”, and “Slave in the Spotlight” became Official Selections in the Sacramento International Film Festival. In addition, “Slave in the Spotlight” became a recent Official Selection in the Underground Indie Film Festival.

Another thing the three aforementioned scripts have in common is that hypnosis plays a pivotal role in the stories. I strongly feel that hypnosis is a fascinating subject that should be explored in more horror films (both features and shorts).

Q. What caused you to become interested in hypnosis as a horror subject?

A. It was the hypnosis scenes in “A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors” that got me interested in taking it as a subject in my horror scripts. I thought the light pendulum used in that film was really cool, especially the scene in which Heather Langenkamp‘s character (Nancy) used it to hypnotize the other characters to rescue Patricia Arquette‘s character (Kristin). Coincidentally, Jennifer Rubin’s character in the film (Taryn) has a Mohawk in her “dream”. She was the major inspiration for the main protagonist in my horror feature script “Enslavement II”.

Q. What are some of your favorite horror movies?

A. Of course “A Nightmare on Elm Street”, the 1984 original that not only made me a horror fan for life but also inspired me to write my very first screenplay in the genre “Demon Crystal”, which was recently optioned by Pulse Pounding Productions. My other favorites are Rob Zombie‘s Halloween films, “The Collector”, “Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2”, “Get Out”, and “Saw”. As far as film franchises go, “Saw” is my all-time favorite (horror or otherwise).

Q. Is there a website or anything where people can contact you about your work or see more about your projects in development?

A. If anyone is interested to know more about my work as a screenwriter, I can be contacted at Oyou78020@hotmail.com.

June 25, 2018

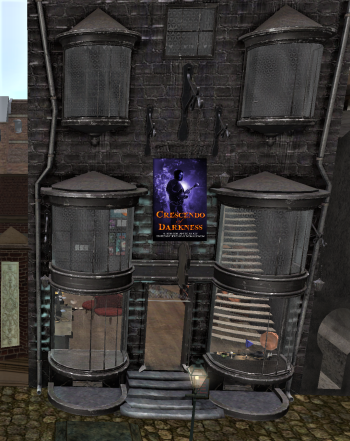

LIVE Second Life event Jun 30th – Crescendo of Darkness Release Party

It’s in SecondLife so I am going to try to be there.

Join HorrorAddicts.net on Second Life

for our Virtual Book Release Party

Sunday, June 30th, 2pm SLT (PST)

HorrorAddicts.net HQ, Baggage Square, Second Life

Live author readings, prizes, and more!

Come celebrate with us!

*************

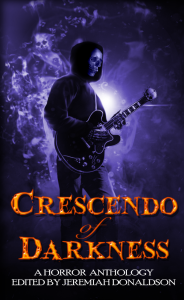

Crescendo of Darkness

Edited by Jeremiah Donaldson

Music has the power to soothe the soul, drive people to obsession, and soundtrack evil plots. Is music the instigator of madness, or the key that unhinges the psychosis within? From guitar lessons in a graveyard and a baby allergic to music, to an infectious homicidal demo and melancholy tunes in a haunted lighthouse, Crescendo of Darkness will quench your thirst for horrifying audio fiction.

HorrorAddicts.net is proud to present fourteen tales of murderous music, demonic performers, and cursed audiophiles.

With stories by: Calvin Demmer, Jeremiah Donaldson, Cara Fox, R.A. Goli, Sarah Gribble,

Kahramanah, Naching T. Kassa, Benjamin Langley, Jeremy Megargee, A. Craig Newman,

Sam Morgan Phillips, Emerian Rich, H.E. Roulo, Daphne Strasert

May 9, 2018

San Mateo County Fair

[image error]

I am excited to announce that I won the following literary prizes at the San Mateo County Fair:

Div. 325-05 Literary Essay, Adult Exhibitor

2nd Place: African American Folklore, Magical Realism and Horror in Toni Morrison Novels, Sumiko Saulson

Div. 326-02 Personal Memoir, Adult Exhibitor

2nd Place: My Life as a Young Adult Urban Fiction Writer, Sumiko Saulson

Div. 329-03 Recorded Lyric Songwriting Contest: Singer/Songwriter/Indie

2nd Place: Sweetest Compassion, Sumiko Saulson

Div. 335-05 Short Story, Science Fiction/Fantasy, Adult

3rd Place: The Ride of Herne and Hespeth, Sumiko Saulson

[image error]

I wrote the literary essay, “African American Folklore, Magical Realism and Horror in Toni Morrison” for HorrorAddicts.net in 2017 for their Black History Month blog series. My Life as a Young Adult Urban Fiction Writer, and The Ride of Herne and Hespeth were both written as a contestant in HorrorAddict’s Next Great Horror Writer Contest in 2017. I finished the contest in 6th Place. Jonathan Fortin won, and was awarded a contract with Crystal Lake Publishing for his debut novel Lilitu, coming out in 2019.

I wrote Sweetest Compassion’s lyrics. The music was written by Mangladat. It was performed by my band, Stagefright. It was recorded by Ephriam Galloway at Greybeard Studios.

I’ll also be moderating a diversity panel Thursday, June 14 6pm to 7pm at the San Mateo Fair, with Laurel Anne Hill and Maria Nieto.

April 13, 2018

When We First Become Other

When We First Become Other

By Sumiko Saulson

Winner, Fall 2017 Berkeley City College / BCC Voice Essay Contest, “Reframing the Other”

It is the very nature of human self-awareness which creates Othering. From birth, we see the world from a personal vantage point. We first take in sounds, smells and images of our personal tribe: parents, siblings, neighbors and grandparents. They are the village to which Self belongs. This is true even for those of us mainstream America views as Other. So how does one first become Othered? This occurs through contact with multicultural groups, and with mainstream media. Once we view ourselves through the lens of mass media, it becomes possible to reframe Self as Other.

In late 1970s, watching a television show called The Jeffersons. I noticed their neighbors, the Willises, an interracial couple, had one white actor and one black actress playing their mixed race children. As a biracial black and Jewish child this made feel a bit like a space alien. The constant string of “zebra” jokes about their mixed heritage added to that feeling. Strangers sometimes stopped our mom on the street to ask questions about me and my brother’s heritage, and ask to touch our hair. But this was the first time an outside authority verified the strangeness of being biracial.

When I became a fiction writer, I sought to remedy the absence of multicultural stories by filling my books with them. For me, it seemed unnatural that stories taking place in diverse metropolitan areas like Los Angeles or New York often have predominately white casts.

It wasn’t until I’d been writing novels for a few years that it occurred to me that I might try introducing race later in the narrative. It was after reading an article about how some of Suzanne Collin’s literary fandom was freaking out about Rue being black in the movie. Although the book clearly described her as dark skinned and having African American features, readers subconsciously reframed the character in their minds as white.

As an experiment, I wrote the first two chapters of my book, “Happiness and Other Diseases,” without revealing the ethnicity of the central character, Flynn Keahi. He’s half Chinese and half Hawaiian. Nowadays I am fairly political, so my heritage is a normal topic of conversation. When I was younger, it wouldn’t come up as often in the day to day living of life. That being the case, I decided to have his ethnicity come up when it seemed most natural in the narrative: that is, through the eyes of a third party, his girlfriend’s mother, upon meeting him for the first time. That way the reader had an attachment to the character before any issues regarding ethnicity came up.

In reframing the Other, one might consider the fact that every single other person on the planet views life initially, and primarily, from the vantage of self. Absent of external Othering forces, a person in a self-segregated environment will view him or herself as quite the norm. The eroticizing of those who are perceived as different or unusual due to ethnic heritage, disability, sexual preference, or gender presentation is rooted in our denial of the Othered person’s self. Self being the vantage point from which we all view the world.

In order to ethically reframe the notion of Other, those of us who have for whatever reason, come to view ourselves as “the norm” or what is usual will have to accept the fact that our perception is biased.

Readers of “The Hunger Games” and “Happiness and Other Diseases” alike threw a filter of whiteness as a default setting onto the character. As a cis-gen female, I run into people who resist terms like cis-gen, even while knowing they exist to dispute the idea that we are “default” or “normal.” This is an attitude people must overcome. We cannot have true equality among diverse populations while clinging to the notion that some of us are “normal” – “default” – or “usual.”

People cling to this attitude even where it is statistically disproven: for example, many white people think of white as the default; Western Media sells it as such, yet white people are only 18% of the global population, therefore a statistical minority. If a statistical minority can believe itself the default due to acculturation, then perhaps we should question the notion of who is actually the Other here.

February 23, 2018

Book Review: Black Magic Women

Kamika Aziza is one of the newer writers and I am tickled pink to see her mentioned here alongside veterans Valjeanne Jeffers and Kenesha Williams.