Paul van Yperen's Blog, page 82

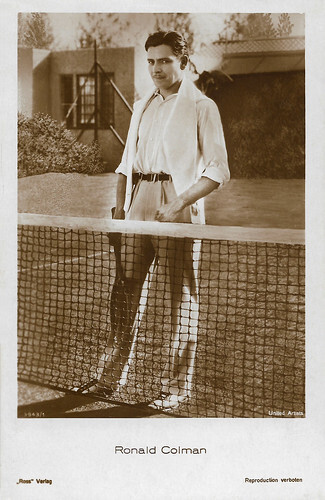

July 2, 2023

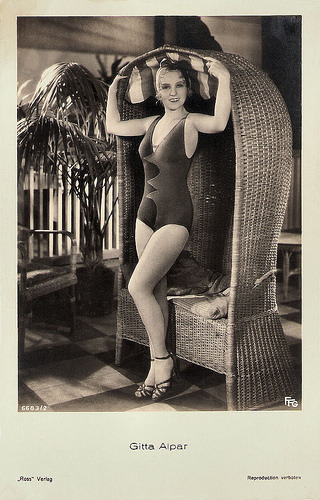

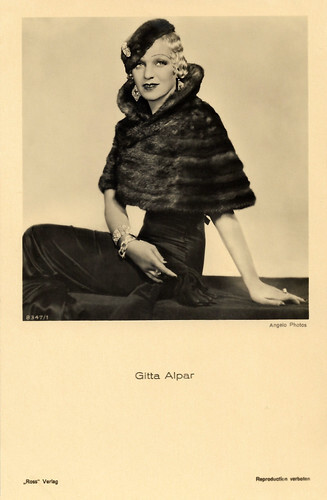

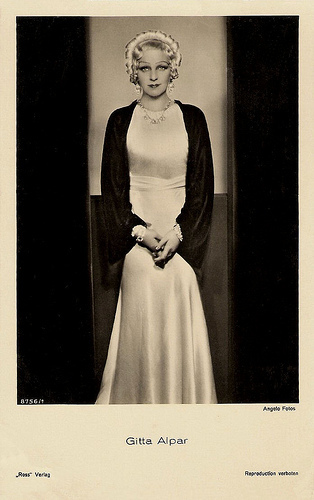

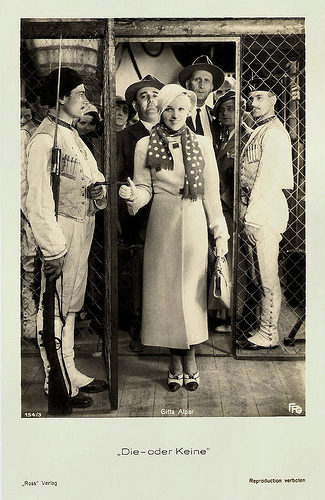

Ruth Taylor

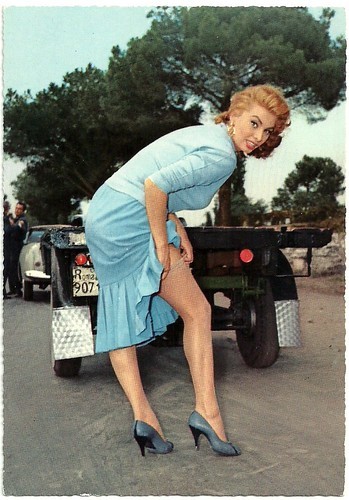

Ruth Taylor (1905-1984) was an American silent film and early talkie actress of the late 1920s. The vivacious blond Mack Sennett comedienne nabbed the most sought-after role in 1928, Lorelei Lee in the silent film version of Anita Loos' Gentleman Prefer Blondes. Her son was the writer, comic, and actor Buck Henry.

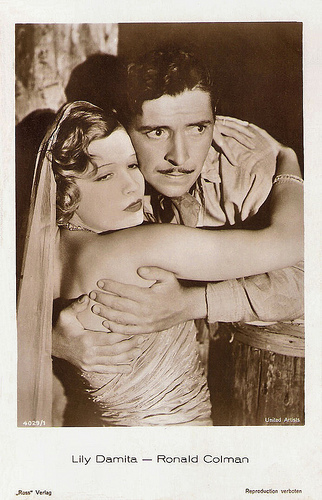

French postcard by Cinémagazine-Edition, no. 611. Photo: Paramount Pictures.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3388/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Paramount Pictures.

The little girl with a big personality

Ruth Alice Taylor was born in 1905 in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Her parents were Norman and Ivah (Bates) Taylor. She was only two years old when her parents decided to move to Portland, Oregon.

She graduated from the University of Oregon, where she discovered amateur theatre. In 1924, at the age of nineteen, Ruth persuaded her mother to take her to Hollywood. There the teenager spent a year working as an extra at Universal Studios.

Responding to an advertisement, the blonde, blue-eyed girl went to a casting call where she was selected by Mack Sennett out of 200 girls to play a blonde in the Harry Langdon comedy Lucky Stars (Harry Edwards, 1925).

Elizabeth Ann at IMDb : "In 1925 she signed a two-year contract with Mack Sennett and became one of his bathing beauties. With her perky smile and blonde spit curls Ruth quickly became one of Sennett's most popular actresses. She had supporting roles in several comedies including the short A Yankee Doodle Duke (Charles Lamont, 1926) and The Pride Of Pikeville (Charles Lamont, 1927) starring Ben Turpin. Ruth was nicknamed "The Little Girl With A Big Personality"."

She also appeared in such Sennett comedies as Lucky Stars with Harry Langdon and the Puppy Love series with Eddy Cline. For two years, she acted alongside Billy Bevan, Andy Clyde, Alice Day, Vernon Dent, Ralph Graves, Raymond McKee, Eddie Quillan and Ben Turpin in both leading and supporting roles.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 2991/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Paramount Pictures.

Blue-eyed, gold-digging Lorelei Lee

When her two-year contract with Mack Sennett came to an end, she went through a period of uncertainty during which, having gone freelance in the hope of playing great characters, she was turned down for all her castings. Finally, in August 1927, she unexpectedly signed with the Paramount Famous Lasky Corporation.

She played the role of blue-eyed, gold-digging Lorelei Lee opposite Alice White as Dorothy Shaw and Ford Sterling as Gus Eisman in the silent film version of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (Malcolm St. Clair, 1928), co-written by Anita Loos based on her 1925 novel.

Her diary reveals that at this time, John Emerson, casting director and co-writer, and director Malcolm St Clair retained her after interviewing two hundred actresses and conducting as many screen tests. "All the blonde actresses of Hollywood were there", she wrote.

Anita Loos, the screenwriter and author of the novel of the same name for which they were looking for the ideal actress to play the main character, also chose Ruth Taylor, telling her at a press conference, in the form of a joke, "Your screen test was the worst, so we're choosing you."

Having become the role of the year, coveted by so many famous actresses, the "chosen one" received congratulations from all sides and went from press conference to photo shoot to photo shoot. Responding to a poll on the best actress for the role, fans sent Paramount Pictures nearly 14,000 letters supporting Ruth Taylor's candidacy. They each received a photo of the actress in return. It was the largest mailing ever recorded by Hollywood for an actress.

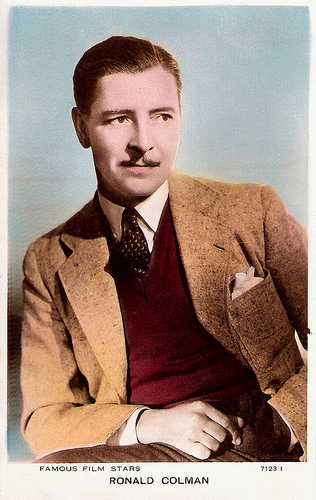

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3802/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Paramount Pictures.

Member of the 1928 WAMPAS Baby Stars class

That same year, following the success of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Ruth Taylor starred in Just Married (Frank R. Strayer, 1929), produced by B. P. Schulberg. It featured a new comedy couple, played by Ruth Taylor and James Hall .

Along with Lupe Vélez , Lina Basquette and Sue Carol, she was a member of the 1928 WAMPAS Baby Stars class.

Ruth Taylor acted in her first talkie A Hint to Brides (Leslie Pearce, 1929) for the Christie Film Company. For Paramount Studios she starred in The College Coquette (George Archainbaud, 1929) with William Collier Jr., and for Columbia Pictures Corporation in This Thing Called Love (Paul L. Stein, 1929) with Edmund Lowe and Constance Bennett .

The next year, she played for Pathé Exchange Incorporated in the short comedy Scrappily Married (Leslie Pearce, 1930) with Bert Roach. In 1930, she married retired USAF Brigadier General and New York stockbroker Paul Steinberg Zuckerman. He had served in the Lafayette Escadrille during World War I and as a senior officer in World War II. She decided to quit making films and became a housewife.

Ruth and Paul lived in Palm Springs and were happily married until he died in 1965. The couple had a son Henry Zuckerman aka Buck Henry. At age 16, he picked up his Equity card in 1946 for a role in the long-running comedy, Life With Father. Later he became the successful screenwriter behind such hits as The Graduate (Mike Nichols, 1967). Ruth Taylor died in Palm Springs in 1984 at the age of 79. She is buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Hollywood Hills, California.

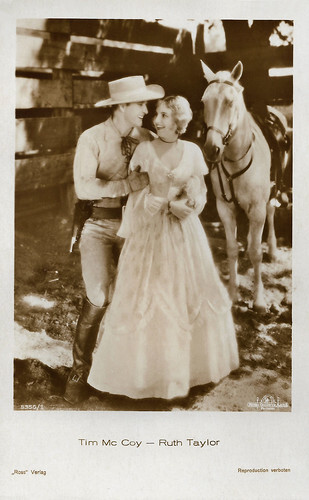

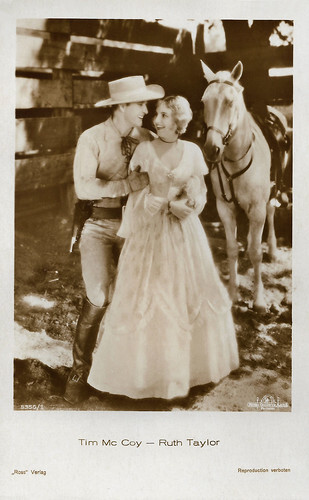

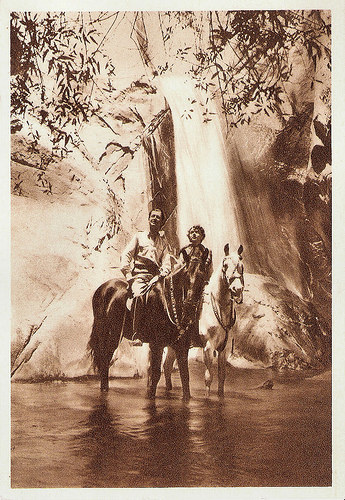

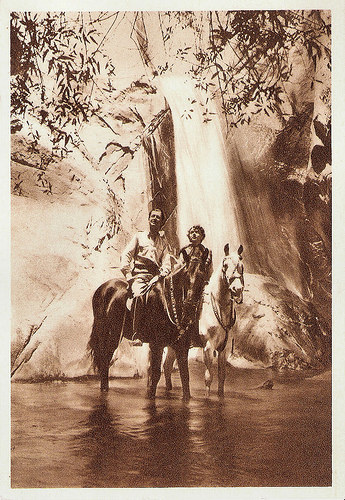

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5356/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Metro Goldwyn Mayer Pictures. Tim McCoy and Ruth Taylor.

Sources: (IMDb), Find A Grave, Wikipedia (French, Spanish and English) and .

French postcard by Cinémagazine-Edition, no. 611. Photo: Paramount Pictures.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3388/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Paramount Pictures.

The little girl with a big personality

Ruth Alice Taylor was born in 1905 in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Her parents were Norman and Ivah (Bates) Taylor. She was only two years old when her parents decided to move to Portland, Oregon.

She graduated from the University of Oregon, where she discovered amateur theatre. In 1924, at the age of nineteen, Ruth persuaded her mother to take her to Hollywood. There the teenager spent a year working as an extra at Universal Studios.

Responding to an advertisement, the blonde, blue-eyed girl went to a casting call where she was selected by Mack Sennett out of 200 girls to play a blonde in the Harry Langdon comedy Lucky Stars (Harry Edwards, 1925).

Elizabeth Ann at IMDb : "In 1925 she signed a two-year contract with Mack Sennett and became one of his bathing beauties. With her perky smile and blonde spit curls Ruth quickly became one of Sennett's most popular actresses. She had supporting roles in several comedies including the short A Yankee Doodle Duke (Charles Lamont, 1926) and The Pride Of Pikeville (Charles Lamont, 1927) starring Ben Turpin. Ruth was nicknamed "The Little Girl With A Big Personality"."

She also appeared in such Sennett comedies as Lucky Stars with Harry Langdon and the Puppy Love series with Eddy Cline. For two years, she acted alongside Billy Bevan, Andy Clyde, Alice Day, Vernon Dent, Ralph Graves, Raymond McKee, Eddie Quillan and Ben Turpin in both leading and supporting roles.

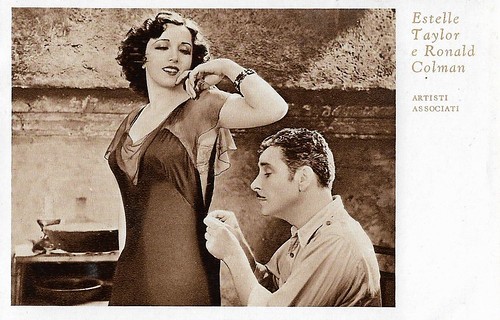

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 2991/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Paramount Pictures.

Blue-eyed, gold-digging Lorelei Lee

When her two-year contract with Mack Sennett came to an end, she went through a period of uncertainty during which, having gone freelance in the hope of playing great characters, she was turned down for all her castings. Finally, in August 1927, she unexpectedly signed with the Paramount Famous Lasky Corporation.

She played the role of blue-eyed, gold-digging Lorelei Lee opposite Alice White as Dorothy Shaw and Ford Sterling as Gus Eisman in the silent film version of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (Malcolm St. Clair, 1928), co-written by Anita Loos based on her 1925 novel.

Her diary reveals that at this time, John Emerson, casting director and co-writer, and director Malcolm St Clair retained her after interviewing two hundred actresses and conducting as many screen tests. "All the blonde actresses of Hollywood were there", she wrote.

Anita Loos, the screenwriter and author of the novel of the same name for which they were looking for the ideal actress to play the main character, also chose Ruth Taylor, telling her at a press conference, in the form of a joke, "Your screen test was the worst, so we're choosing you."

Having become the role of the year, coveted by so many famous actresses, the "chosen one" received congratulations from all sides and went from press conference to photo shoot to photo shoot. Responding to a poll on the best actress for the role, fans sent Paramount Pictures nearly 14,000 letters supporting Ruth Taylor's candidacy. They each received a photo of the actress in return. It was the largest mailing ever recorded by Hollywood for an actress.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3802/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Paramount Pictures.

Member of the 1928 WAMPAS Baby Stars class

That same year, following the success of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Ruth Taylor starred in Just Married (Frank R. Strayer, 1929), produced by B. P. Schulberg. It featured a new comedy couple, played by Ruth Taylor and James Hall .

Along with Lupe Vélez , Lina Basquette and Sue Carol, she was a member of the 1928 WAMPAS Baby Stars class.

Ruth Taylor acted in her first talkie A Hint to Brides (Leslie Pearce, 1929) for the Christie Film Company. For Paramount Studios she starred in The College Coquette (George Archainbaud, 1929) with William Collier Jr., and for Columbia Pictures Corporation in This Thing Called Love (Paul L. Stein, 1929) with Edmund Lowe and Constance Bennett .

The next year, she played for Pathé Exchange Incorporated in the short comedy Scrappily Married (Leslie Pearce, 1930) with Bert Roach. In 1930, she married retired USAF Brigadier General and New York stockbroker Paul Steinberg Zuckerman. He had served in the Lafayette Escadrille during World War I and as a senior officer in World War II. She decided to quit making films and became a housewife.

Ruth and Paul lived in Palm Springs and were happily married until he died in 1965. The couple had a son Henry Zuckerman aka Buck Henry. At age 16, he picked up his Equity card in 1946 for a role in the long-running comedy, Life With Father. Later he became the successful screenwriter behind such hits as The Graduate (Mike Nichols, 1967). Ruth Taylor died in Palm Springs in 1984 at the age of 79. She is buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Hollywood Hills, California.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5356/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Metro Goldwyn Mayer Pictures. Tim McCoy and Ruth Taylor.

Sources: (IMDb), Find A Grave, Wikipedia (French, Spanish and English) and .

Published on July 02, 2023 22:00

July 1, 2023

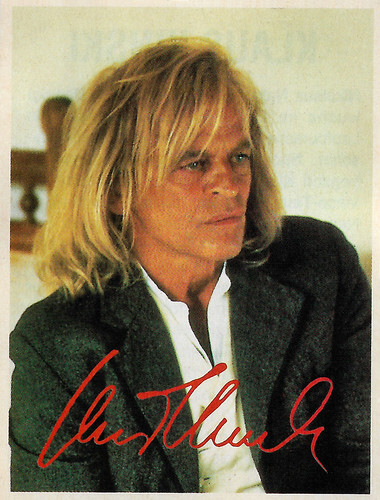

Klaus Kinski

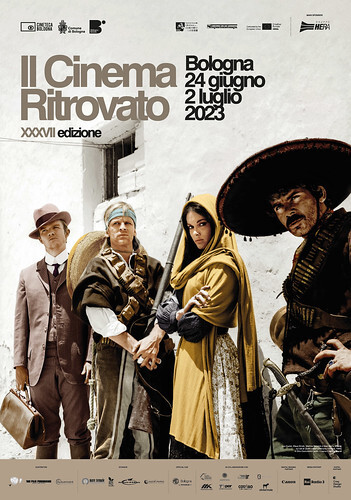

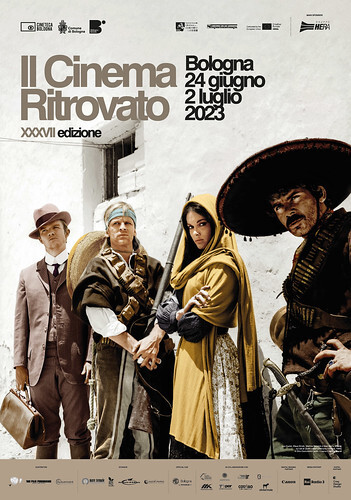

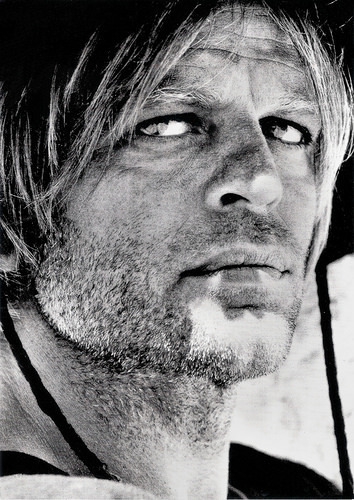

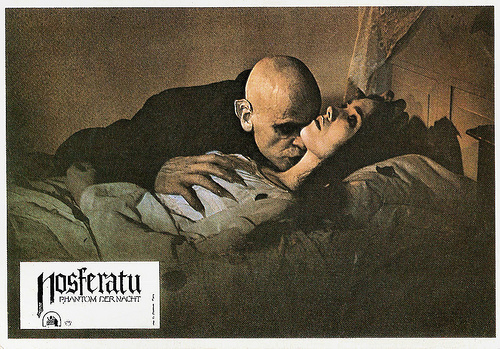

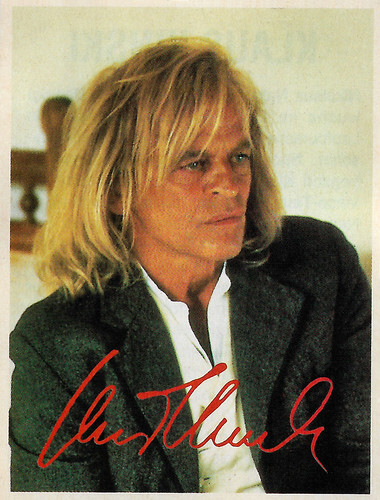

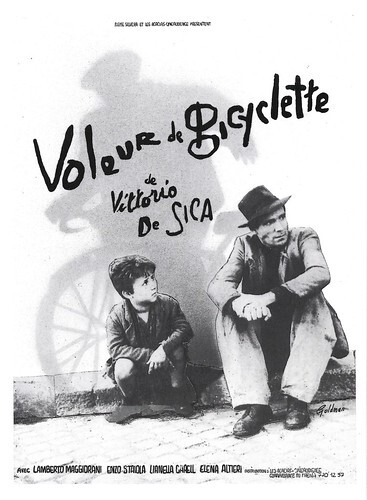

Today is the final day of Il Cinema Ritrovato 2023. The official poster of this year's festival showed Lou Castel, Klaus Kinski, Martine Beswick and Gian Maria Volonté, with their eyes fixed on the horizon on the set of Quién sabe?/El chuncho, quien sabe?/A Bullet for the General (Damiano Damiani, 1966). On the tenth anniversary of the death of Damiani, Il Cinema Ritrovato remembers him with the restoration of Quién sabe?. In this post, we focus on one of the stars of the film, the intense and eccentric Klaus Kinski (1926–1991), one of the most colourful stars of European cinema. In a film career of over 40 years, the German actor appeared in more than 130 films, including numerous parts as a villain in Edgar Wallace thrillers and Spaghetti Westerns. The talented but tempestuous Kinski is probably best known for his riveting star turn in Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes/Aguirre: The Wrath of God (1972), Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht/Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), Fitzcarraldo (1982) and other films directed by Werner Herzog.

The official poster of Il Cinema Ritrovato 2023. Photo: Divo Cavicchioli / Surf Film. Lou Castel, Klaus Kinski, Martine Beswick and Gian Maria Volonté, with their eyes fixed on the horizon. A shot taken by Divo Cavicchioli on the 1966 set of Quién sabe?/El chuncho, quien sabe?/A Bullet for the General by Damiano Damiani.

The official poster of Il Cinema Ritrovato 2023. Photo: Divo Cavicchioli / Surf Film. Lou Castel, Klaus Kinski, Martine Beswick and Gian Maria Volonté, with their eyes fixed on the horizon. A shot taken by Divo Cavicchioli on the 1966 set of Quién sabe?/El chuncho, quien sabe?/A Bullet for the General by Damiano Damiani.

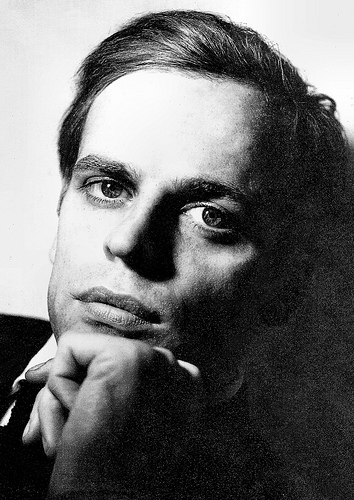

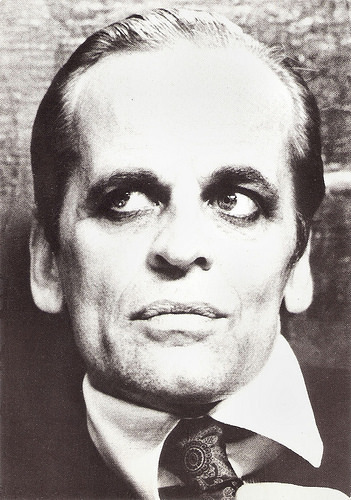

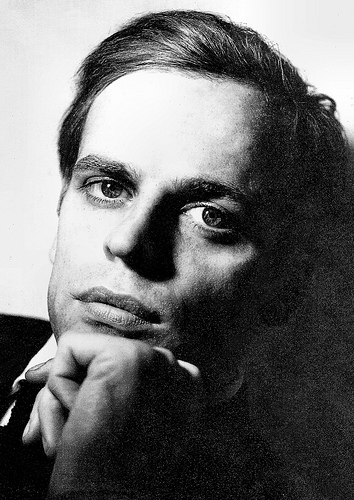

German postcard by Limited Editions, AZ/Drehbuch, Film, no. 124. Photo: I. Letto, ca. 1956.

French postcard by Humour a la Carte, Paris, no. 82-11.

French postcard by Ébullitions, no. 26.

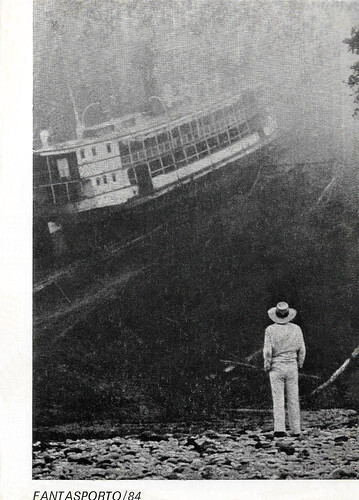

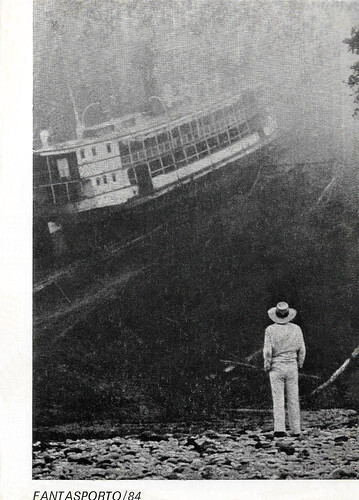

Portugese postcard for Concurso Fantasporto 83 by IV Edicao Internacional de Cinema Fantastico, Porto, 1984. Klaus Kinski in Fitzcarraldo (Werner Herzog, 1982).

Wild and unconventional behaviour

Klaus Kinski was born Nikolaus Günther Nakszyński in Zoppot, Danzig, Germany (now Sopot, Poland), in 1926. He was the son of a German father of Polish descent, Bruno Nakszyński, a pharmacist and a failed opera singer, and a German mother, Susanne Nakszyński-Lutze, a nurse and a daughter of a local pastor. He had three older siblings: Inge, Arne and Hans-Joachim. Because of the depression, the poor family was unable to make a living in Danzig and was forced to move to Berlin in 1931. They settled in a flat in the suburb of Schöneberg. From 1936 on, Kinski attended the Prinz-Heinrich-Gymnasium there.

During World War II, the 16-year-old enlisted in the Wehrmacht. Kinski saw no action until the winter of 1944 when his unit was transferred to the Netherlands. His obituary in Variety magazine states that there he was wounded and captured by the British on the second day of combat, but Kinski's autobiography Ich bin so wild nach deinem Erdbeermund (I Am So Wild About Your Strawberry Mouth, 1975) claims he made a conscious decision to desert.

However, Kinski was transferred to the Prisoner of War Camp 186 in Colchester, Great Britain. The ship transporting him to England was torpedoed by a German U-Boat but managed to arrive safely at its destination. At the POW camp, Kinski played his first theatre roles in shows staged by fellow prisoners intending to maintain morale. Following the end of the war in Europe in May 1945, Kinski was finally allowed in 1946 to return to Germany, after spending a year and four months in captivity.

Arriving in Berlin, Kinski learned his father had died during the war and his mother had been killed in an Allied air attack. Without having ever attended any professional training, he started out as an actor, first at a small touring company in Offenburg and already using his new name Klaus Kinski. He was hired by the renowned Schlosspark-Theater in Berlin but was fired by the manager in 1947 due to his unpredictable behaviour.

Other companies followed, but his already wild and unconventional behaviour regularly got him into trouble. His first film role was a small part in Morituri (Eugen York, 1948) a drama about refugees from a concentration camp. In 1950, he stayed in a psychiatric hospital for three days; medical records from the period listed a preliminary diagnosis of schizophrenia. He only could find bit roles in films, and in 1955 Kinski twice tried to commit suicide.

Vintage photo.

Danish postcard by Forlaget Holger Danske, no. 115. Photo: publicity still for Das Geheimnis der schwarzen Witwe/The Secret of the Black Widow (Franz Josef Gottlieb, 1963).

Danish postcard by Forlaget Holger Danske, no. 124. Photo: defd / Kinoarchiv Hamburg.

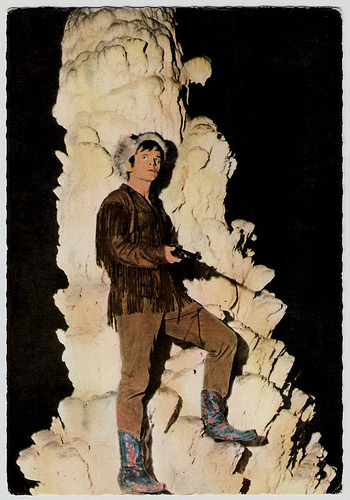

German postcard by Graphima, Berlin, no. 10. Photo: Klaus Kinski in Der letzte Ritt nach Santa Cruz/The Last Ride to Santa Cruz (Rolf Olsen, 1964).

Danish postcard by Forlaget Holger Danske, no. 704. Photo: publicity still for E Dio disse a Caino.../And God Said to Cain (Antonio Margheriti, 1970).

Effective screen villain

Then Klaus Kinski got a supporting part in Ludwig II: Glanz und Ende eines Königs/Ludwig II (Helmut Käutner, 1955) about the frustrated and tragic King Ludwig II of Bavaria played by O.W. Fischer . More supporting parts in German films followed. In March 1956 Kinski made one single guest appearance at Vienna's Burgtheater in Goethe's Torquato Tasso.

Although respected by his colleagues, and cheered by the audience, Kinski's hope to get a permanent contract was not fulfilled, as the Burgtheater's management ultimately became aware of the actor's earlier difficulties in Germany. He unsuccessfully tried to sue the company. Living jobless in Vienna, and without any prospects for his future, Kinski reinvented himself as a monologist and spoken word artist. He presented the prose and verse of François Villon, William Shakespeare and Oscar Wilde among others. Thus he managed to establish himself as a well-known actor touring Austria, Germany, and Switzerland with his shows.

In 1960 he returned to the cinema as a sinister character on the verge between genius and madness in the thriller Der Rächer/The Avenger (Karl Anton, 1960) based on a crime novel by British writer Edgar Wallace. In another Wallace adaptation, Die toten Augen von London/The Dead Eyes of London (Alfred Vohrer, 1961), Kinski’s psychopathic bad guy refused any personal guilt for his evil deeds and claimed to have only followed the orders given to him. During the 1960s, Kinski appeared in several Wallace Krimis, which enjoyed enormous success in Germany and are now considered cult classics.

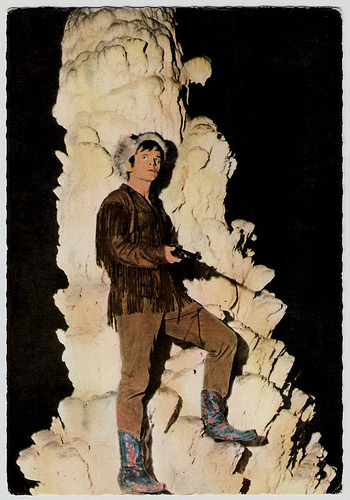

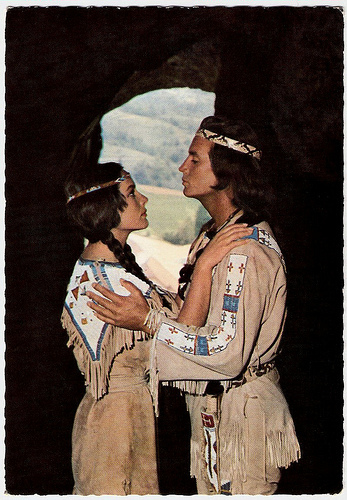

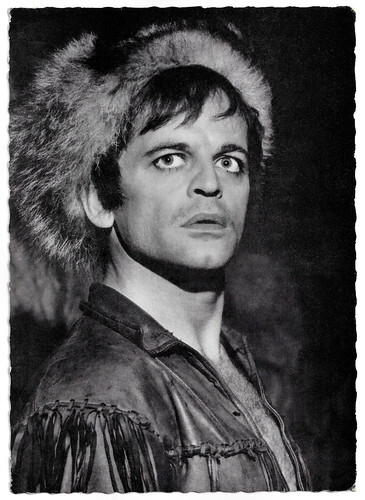

He also appeared in many other European genre films such as the Karl May Western Winnetou - 2. Teil/Last of the Renegades (Harald Reinl, 1964) featuring Pierre Brice . In these films, he built a reputation as an effective screen villain. In 1964, he relocated to Italy and was cast in the international production Doctor Zhivago (David Lean, 1965) as an Anarchist prisoner on his way to the Gulag. That year he also had a small part as a hunchback in the classic Italian western Per qualche dollaro in più/For Few Dollars More (Sergio Leone, 1965) starring Clint Eastwood .

Roles in numerous other Spaghetti westerns followed, including El chuncho, quien sabe?/A Bullet for the General (Damiano Damiani, 1966) with Gian Maria Volonté, Il grande silenzio/The Great Silence (Sergio Corbucci, 1968) starring Jean-Louis Trintignant , and Un genio, due compari, un pollo/A Genius, Two Partners and a Dupe (Damiano Damiani, 1975) with Terence Hill . When the Spaghetti Western genre was over its top, Kinski started to appear in other exploitation genres. Often these films proved to be brainless trash.

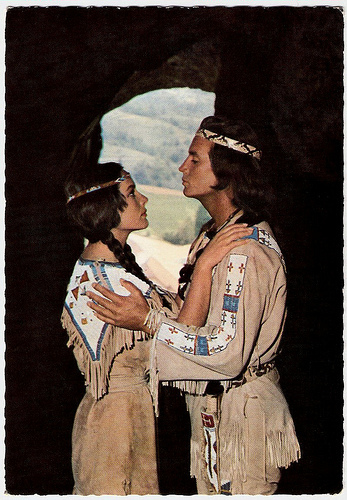

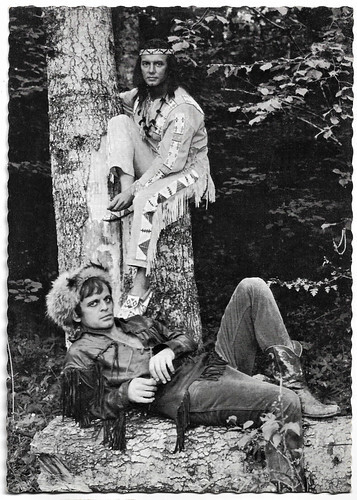

German postcard, no. R 21. Photo: publicity still for Winnetou - 2. Teil/Last of the Renegades (Harald Reinl, 1964).

German postcard, no. R 24. Photo: still from Winnetou - 2. Teil/Last of the Renegades (Harald Reinl, 1964) with Karin Dor as Ribanna and Pierre Brice as Winnetou.

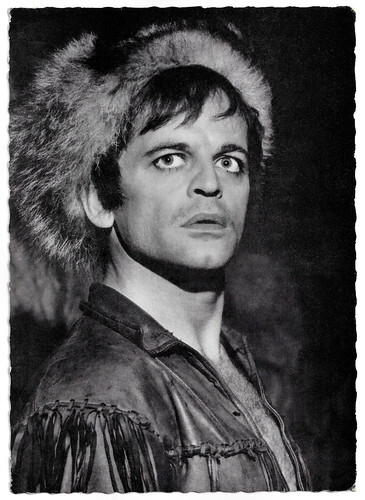

German postcard by Filmbilder-Vertrieb Ernst Freihoff, Essen, no. 891. Photo: Lothar Winkler. Klaus Kinski in Winnetou - 2. Teil/Last of the Renegades (Harald Reinl, 1964).

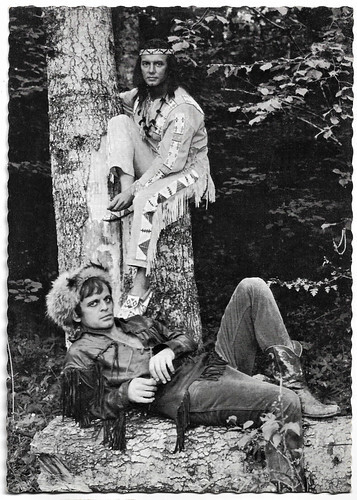

With Pierre Brice . German postcard by Filmbilder-Vertrieb Ernst Freihoff, Essen, no. 901. Photo: Lothar Winkler.

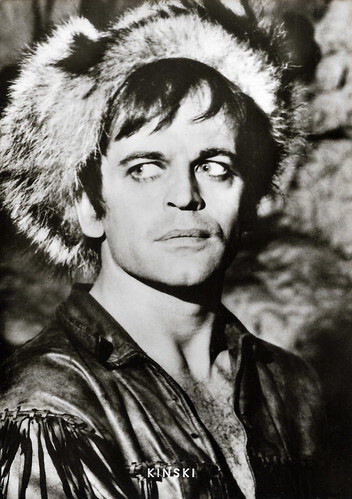

German postcard by Graphima, no. 1. Photo: publicity still for Winnetou - 2. Teil/Last of the Renegades (Harald Reinl, 1964).

An obsessive, terrifying, and emotionally unpredictable antihero

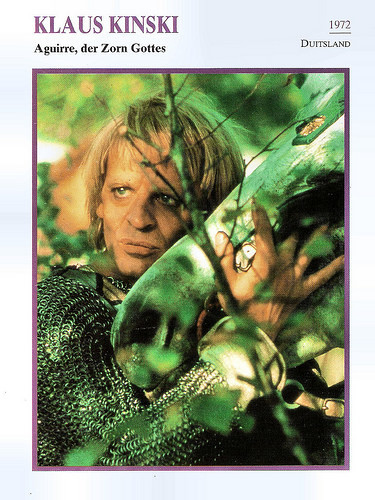

In 1972, in between his countless appearances in genre and exploitation films, Klaus Kinski suddenly found international recognition with the German production Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes/Aguirre: The Wrath of God (Werner Herzog, 1972).

At AllMovie , Karl Williams writes: “The most famed and well-regarded collaboration between New German Cinema director Werner Herzog and his frequent leading man, Klaus Kinski, this epic historical drama was legendary for the arduousness of its on-location filming and the convincing zealous obsession employed by Kinski in playing the title role. Exhausted and near to admitting failure in its quest for riches, the 1650-51 expedition of Spanish conquistador Gonzalo Pizarro (Alejandro Repulles) bogs down in the impenetrable jungles of Peru.

As a last-ditch effort to locate treasure, Pizarro orders a party to scout ahead for signs of El Dorado, the fabled seven cities of gold. In command are a trio of nobles, Pedro de Ursua (Ruy Guerra), Fernando de Guzman (Peter Berling), and Lope de Aguirre (Kinski). Travelling by river raft, the explorers are besieged by hostile natives, disease, starvation and treacherous waters. Crazed with greed and mad with power, Aguirre takes over the enterprise, slaughtering any that oppose him.”

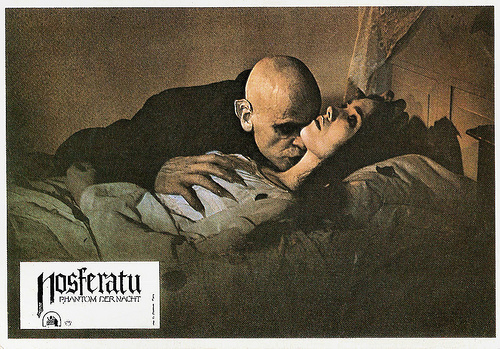

Kinski delivered a bravura performance that typified his screen image: that of an obsessive, terrifying, and emotionally unpredictable antihero. Kinski and Herzog would make five films together, including Woyzeck (1978), Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht/Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979) with Isabelle Adjani , and Fitzcarraldo (1982) with Claudia Cardinale .

The volatile love-hate relationship between Kinski and his equally driven and obsessive director Herzog resulted in some of the best work from both men, and both are best known for the films on which they collaborated. Kinski and Herzog pushed each other to extremes over a 15-year working relationship, which finally ended after filming Cobra Verde (Werner Herzog, 1987), a production plagued by volcanic clashes between the star and director, involving violent physical altercations and mutual death threats.

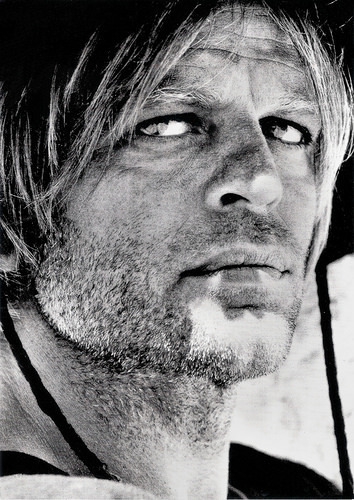

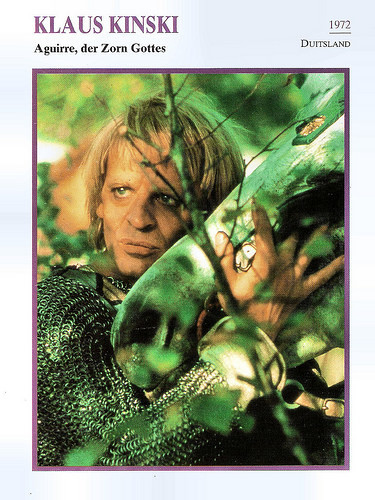

Dutch collectors card in the series 'Filmsterren: een portret' by Edito Service, 1995. Photo: Pele / Stills. Publicity still for Aguirre der Zorn Gottes/Aguirre, the Wrath of God (Werner Herzog, 1972).

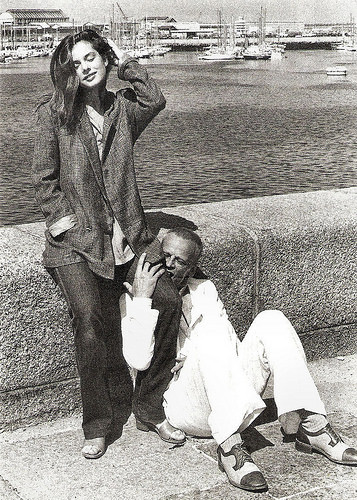

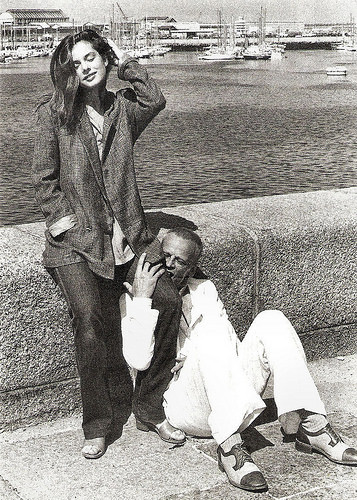

With his daughter Nastassja Kinski . French postcard in the Collection Cinéma by Editions Malibran, Paris, no. CF 50. Photo: Guidotti, 1978.

British postcard by Moviedrome, no. M45. Photo: 20th Century Fox. Publicity still for Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht/Nosferatu the Vampyre (Werner Herzog, 1979) with Isabelle Adjani .

'Cretins' or 'scum'

The Encyclopaedia Britannica writes that Klaus Kinski “disdained his chosen profession, once saying, ‘I wish I’d never been an actor. I’d rather have been a streetwalker, selling my body, than selling my tears and my laughter, my grief and my joy’. Numerous offers from prestigious directors—whom Kinski categorised as ‘cretins’ or ‘scum’—were refused; he worked only when the money suited him.”

Kinski was also notorious – and in high demand – for his scandalous TV appearances and interviews. The scandals paid off. Although he continued to appear for the money in countless trash films, Kinski also starred in such respectable films as the French melodrama L'important c'est d'aimer/The Main Thing Is to Love (Andrzej Zulawski, 1975) starring a memorable Romy Schneider , and the Oscar-nominated Israeli production Mivtsa Yonatan/Operation Thunderbolt (Menahem Golan, 1977), based on the 1976 hijacking of a Tel Aviv-Athens-Paris Air France flight and the daring rescue of its 104 passengers in Entebbe, Uganda.

In the 1980s Kinski appeared prominently in such Hollywood productions as the comedy Buddy Buddy (Billy Wilder, 1981) as a neurotic sex scientist opposite Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau, and the thriller The Little Drummer Girl (George Roy Hill, 1984) featuring Diane Keaton. Kinski’s last film was Kinski Paganini (Klaus Kinski, 1989), in which he played the 19th-century ‘devil’ violinist Niccolò Paganini. He also wrote and directed the film and his wife Debora and his son Nikolai also starred in the film. The production was marked by chaos and clashes between Kinski and his producers, who accused him of turning their production into a pornographic film and sued him in court. The result was a commercial and critical flop.

Kinski reinforced his image as a wild-eyed, sex-crazed maniac in his autobiography 'Ich bin so wild nach deinem Erdbeermund' (1975). In 1988 he updated and rereleased it as 'Ich brauche Liebe' (All I Need Is Love) and in 1997 it was again rereleased as 'Kinski Uncut'. The book infuriated many, and prompted his daughter Nastassja Kinski to file a libel suit against him. Werner Herzog would later say in his retrospective film Mein liebster Feind - Klaus Kinski/Kinski, My Best Fiend (Werner Herzog, 1999) that much of the autobiography was fabricated to generate sales; the two even collaborated on the insults about the director.

Klaus Kinski died of a heart attack in Lagunitas, California, U.S. at age 65. His ashes were scattered into the Pacific Ocean. He was married four times: to Gislinde Kühbeck (1952-1955), Brigitte Ruth Tocki (1960-1971), Minhoi Geneviève Loanic (1971-1979), and to Debora Caprioglio (1987-1989). His three children Pola Kinski (1952), Nastassja Kinski (1961) and Nikolai Kinski (1976) are all actors. In 2006 Christian David published the first comprehensive biography based on newly discovered archived material, personal letters and interviews with Kinski's friends and colleagues.

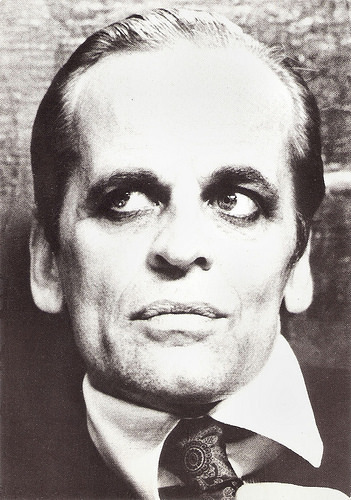

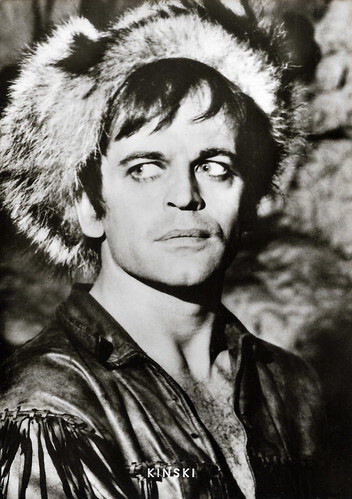

Small German collectors card.

Trailer for Il grande silenzio/The Great Silence (Sergio Corbucci, 1968). Dource: Danios12345 (YouTube).

Trailer for Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht/Nosferatu the Vampyre (Werner Herzog, 1979). Source: Danios12345 (YouTube).

Long scene from Mein liebster Feind - Klaus Kinski/Kinski, My Best Fiend (Werner Herzog, 1999) with a raging Kinski during the shooting of Fitzcarraldo (1982). Source: Baranowski (YouTube).

Sources: Dan Schneider (Alt Film Guide), (IMDb), Hal Erickson (AllMovie), Karl Williams (AllMovie), Encyclopaedia Britannica, Filmportal.de, Wikipedia and .

The official poster of Il Cinema Ritrovato 2023. Photo: Divo Cavicchioli / Surf Film. Lou Castel, Klaus Kinski, Martine Beswick and Gian Maria Volonté, with their eyes fixed on the horizon. A shot taken by Divo Cavicchioli on the 1966 set of Quién sabe?/El chuncho, quien sabe?/A Bullet for the General by Damiano Damiani.

The official poster of Il Cinema Ritrovato 2023. Photo: Divo Cavicchioli / Surf Film. Lou Castel, Klaus Kinski, Martine Beswick and Gian Maria Volonté, with their eyes fixed on the horizon. A shot taken by Divo Cavicchioli on the 1966 set of Quién sabe?/El chuncho, quien sabe?/A Bullet for the General by Damiano Damiani.

German postcard by Limited Editions, AZ/Drehbuch, Film, no. 124. Photo: I. Letto, ca. 1956.

French postcard by Humour a la Carte, Paris, no. 82-11.

French postcard by Ébullitions, no. 26.

Portugese postcard for Concurso Fantasporto 83 by IV Edicao Internacional de Cinema Fantastico, Porto, 1984. Klaus Kinski in Fitzcarraldo (Werner Herzog, 1982).

Wild and unconventional behaviour

Klaus Kinski was born Nikolaus Günther Nakszyński in Zoppot, Danzig, Germany (now Sopot, Poland), in 1926. He was the son of a German father of Polish descent, Bruno Nakszyński, a pharmacist and a failed opera singer, and a German mother, Susanne Nakszyński-Lutze, a nurse and a daughter of a local pastor. He had three older siblings: Inge, Arne and Hans-Joachim. Because of the depression, the poor family was unable to make a living in Danzig and was forced to move to Berlin in 1931. They settled in a flat in the suburb of Schöneberg. From 1936 on, Kinski attended the Prinz-Heinrich-Gymnasium there.

During World War II, the 16-year-old enlisted in the Wehrmacht. Kinski saw no action until the winter of 1944 when his unit was transferred to the Netherlands. His obituary in Variety magazine states that there he was wounded and captured by the British on the second day of combat, but Kinski's autobiography Ich bin so wild nach deinem Erdbeermund (I Am So Wild About Your Strawberry Mouth, 1975) claims he made a conscious decision to desert.

However, Kinski was transferred to the Prisoner of War Camp 186 in Colchester, Great Britain. The ship transporting him to England was torpedoed by a German U-Boat but managed to arrive safely at its destination. At the POW camp, Kinski played his first theatre roles in shows staged by fellow prisoners intending to maintain morale. Following the end of the war in Europe in May 1945, Kinski was finally allowed in 1946 to return to Germany, after spending a year and four months in captivity.

Arriving in Berlin, Kinski learned his father had died during the war and his mother had been killed in an Allied air attack. Without having ever attended any professional training, he started out as an actor, first at a small touring company in Offenburg and already using his new name Klaus Kinski. He was hired by the renowned Schlosspark-Theater in Berlin but was fired by the manager in 1947 due to his unpredictable behaviour.

Other companies followed, but his already wild and unconventional behaviour regularly got him into trouble. His first film role was a small part in Morituri (Eugen York, 1948) a drama about refugees from a concentration camp. In 1950, he stayed in a psychiatric hospital for three days; medical records from the period listed a preliminary diagnosis of schizophrenia. He only could find bit roles in films, and in 1955 Kinski twice tried to commit suicide.

Vintage photo.

Danish postcard by Forlaget Holger Danske, no. 115. Photo: publicity still for Das Geheimnis der schwarzen Witwe/The Secret of the Black Widow (Franz Josef Gottlieb, 1963).

Danish postcard by Forlaget Holger Danske, no. 124. Photo: defd / Kinoarchiv Hamburg.

German postcard by Graphima, Berlin, no. 10. Photo: Klaus Kinski in Der letzte Ritt nach Santa Cruz/The Last Ride to Santa Cruz (Rolf Olsen, 1964).

Danish postcard by Forlaget Holger Danske, no. 704. Photo: publicity still for E Dio disse a Caino.../And God Said to Cain (Antonio Margheriti, 1970).

Effective screen villain

Then Klaus Kinski got a supporting part in Ludwig II: Glanz und Ende eines Königs/Ludwig II (Helmut Käutner, 1955) about the frustrated and tragic King Ludwig II of Bavaria played by O.W. Fischer . More supporting parts in German films followed. In March 1956 Kinski made one single guest appearance at Vienna's Burgtheater in Goethe's Torquato Tasso.

Although respected by his colleagues, and cheered by the audience, Kinski's hope to get a permanent contract was not fulfilled, as the Burgtheater's management ultimately became aware of the actor's earlier difficulties in Germany. He unsuccessfully tried to sue the company. Living jobless in Vienna, and without any prospects for his future, Kinski reinvented himself as a monologist and spoken word artist. He presented the prose and verse of François Villon, William Shakespeare and Oscar Wilde among others. Thus he managed to establish himself as a well-known actor touring Austria, Germany, and Switzerland with his shows.

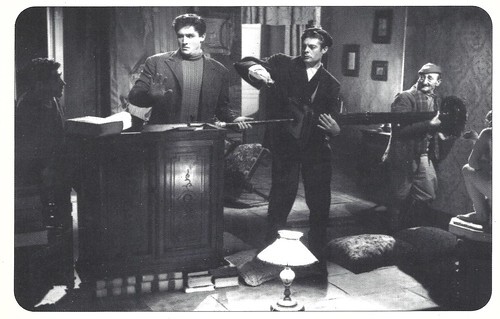

In 1960 he returned to the cinema as a sinister character on the verge between genius and madness in the thriller Der Rächer/The Avenger (Karl Anton, 1960) based on a crime novel by British writer Edgar Wallace. In another Wallace adaptation, Die toten Augen von London/The Dead Eyes of London (Alfred Vohrer, 1961), Kinski’s psychopathic bad guy refused any personal guilt for his evil deeds and claimed to have only followed the orders given to him. During the 1960s, Kinski appeared in several Wallace Krimis, which enjoyed enormous success in Germany and are now considered cult classics.

He also appeared in many other European genre films such as the Karl May Western Winnetou - 2. Teil/Last of the Renegades (Harald Reinl, 1964) featuring Pierre Brice . In these films, he built a reputation as an effective screen villain. In 1964, he relocated to Italy and was cast in the international production Doctor Zhivago (David Lean, 1965) as an Anarchist prisoner on his way to the Gulag. That year he also had a small part as a hunchback in the classic Italian western Per qualche dollaro in più/For Few Dollars More (Sergio Leone, 1965) starring Clint Eastwood .

Roles in numerous other Spaghetti westerns followed, including El chuncho, quien sabe?/A Bullet for the General (Damiano Damiani, 1966) with Gian Maria Volonté, Il grande silenzio/The Great Silence (Sergio Corbucci, 1968) starring Jean-Louis Trintignant , and Un genio, due compari, un pollo/A Genius, Two Partners and a Dupe (Damiano Damiani, 1975) with Terence Hill . When the Spaghetti Western genre was over its top, Kinski started to appear in other exploitation genres. Often these films proved to be brainless trash.

German postcard, no. R 21. Photo: publicity still for Winnetou - 2. Teil/Last of the Renegades (Harald Reinl, 1964).

German postcard, no. R 24. Photo: still from Winnetou - 2. Teil/Last of the Renegades (Harald Reinl, 1964) with Karin Dor as Ribanna and Pierre Brice as Winnetou.

German postcard by Filmbilder-Vertrieb Ernst Freihoff, Essen, no. 891. Photo: Lothar Winkler. Klaus Kinski in Winnetou - 2. Teil/Last of the Renegades (Harald Reinl, 1964).

With Pierre Brice . German postcard by Filmbilder-Vertrieb Ernst Freihoff, Essen, no. 901. Photo: Lothar Winkler.

German postcard by Graphima, no. 1. Photo: publicity still for Winnetou - 2. Teil/Last of the Renegades (Harald Reinl, 1964).

An obsessive, terrifying, and emotionally unpredictable antihero

In 1972, in between his countless appearances in genre and exploitation films, Klaus Kinski suddenly found international recognition with the German production Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes/Aguirre: The Wrath of God (Werner Herzog, 1972).

At AllMovie , Karl Williams writes: “The most famed and well-regarded collaboration between New German Cinema director Werner Herzog and his frequent leading man, Klaus Kinski, this epic historical drama was legendary for the arduousness of its on-location filming and the convincing zealous obsession employed by Kinski in playing the title role. Exhausted and near to admitting failure in its quest for riches, the 1650-51 expedition of Spanish conquistador Gonzalo Pizarro (Alejandro Repulles) bogs down in the impenetrable jungles of Peru.

As a last-ditch effort to locate treasure, Pizarro orders a party to scout ahead for signs of El Dorado, the fabled seven cities of gold. In command are a trio of nobles, Pedro de Ursua (Ruy Guerra), Fernando de Guzman (Peter Berling), and Lope de Aguirre (Kinski). Travelling by river raft, the explorers are besieged by hostile natives, disease, starvation and treacherous waters. Crazed with greed and mad with power, Aguirre takes over the enterprise, slaughtering any that oppose him.”

Kinski delivered a bravura performance that typified his screen image: that of an obsessive, terrifying, and emotionally unpredictable antihero. Kinski and Herzog would make five films together, including Woyzeck (1978), Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht/Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979) with Isabelle Adjani , and Fitzcarraldo (1982) with Claudia Cardinale .

The volatile love-hate relationship between Kinski and his equally driven and obsessive director Herzog resulted in some of the best work from both men, and both are best known for the films on which they collaborated. Kinski and Herzog pushed each other to extremes over a 15-year working relationship, which finally ended after filming Cobra Verde (Werner Herzog, 1987), a production plagued by volcanic clashes between the star and director, involving violent physical altercations and mutual death threats.

Dutch collectors card in the series 'Filmsterren: een portret' by Edito Service, 1995. Photo: Pele / Stills. Publicity still for Aguirre der Zorn Gottes/Aguirre, the Wrath of God (Werner Herzog, 1972).

With his daughter Nastassja Kinski . French postcard in the Collection Cinéma by Editions Malibran, Paris, no. CF 50. Photo: Guidotti, 1978.

British postcard by Moviedrome, no. M45. Photo: 20th Century Fox. Publicity still for Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht/Nosferatu the Vampyre (Werner Herzog, 1979) with Isabelle Adjani .

'Cretins' or 'scum'

The Encyclopaedia Britannica writes that Klaus Kinski “disdained his chosen profession, once saying, ‘I wish I’d never been an actor. I’d rather have been a streetwalker, selling my body, than selling my tears and my laughter, my grief and my joy’. Numerous offers from prestigious directors—whom Kinski categorised as ‘cretins’ or ‘scum’—were refused; he worked only when the money suited him.”

Kinski was also notorious – and in high demand – for his scandalous TV appearances and interviews. The scandals paid off. Although he continued to appear for the money in countless trash films, Kinski also starred in such respectable films as the French melodrama L'important c'est d'aimer/The Main Thing Is to Love (Andrzej Zulawski, 1975) starring a memorable Romy Schneider , and the Oscar-nominated Israeli production Mivtsa Yonatan/Operation Thunderbolt (Menahem Golan, 1977), based on the 1976 hijacking of a Tel Aviv-Athens-Paris Air France flight and the daring rescue of its 104 passengers in Entebbe, Uganda.

In the 1980s Kinski appeared prominently in such Hollywood productions as the comedy Buddy Buddy (Billy Wilder, 1981) as a neurotic sex scientist opposite Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau, and the thriller The Little Drummer Girl (George Roy Hill, 1984) featuring Diane Keaton. Kinski’s last film was Kinski Paganini (Klaus Kinski, 1989), in which he played the 19th-century ‘devil’ violinist Niccolò Paganini. He also wrote and directed the film and his wife Debora and his son Nikolai also starred in the film. The production was marked by chaos and clashes between Kinski and his producers, who accused him of turning their production into a pornographic film and sued him in court. The result was a commercial and critical flop.

Kinski reinforced his image as a wild-eyed, sex-crazed maniac in his autobiography 'Ich bin so wild nach deinem Erdbeermund' (1975). In 1988 he updated and rereleased it as 'Ich brauche Liebe' (All I Need Is Love) and in 1997 it was again rereleased as 'Kinski Uncut'. The book infuriated many, and prompted his daughter Nastassja Kinski to file a libel suit against him. Werner Herzog would later say in his retrospective film Mein liebster Feind - Klaus Kinski/Kinski, My Best Fiend (Werner Herzog, 1999) that much of the autobiography was fabricated to generate sales; the two even collaborated on the insults about the director.

Klaus Kinski died of a heart attack in Lagunitas, California, U.S. at age 65. His ashes were scattered into the Pacific Ocean. He was married four times: to Gislinde Kühbeck (1952-1955), Brigitte Ruth Tocki (1960-1971), Minhoi Geneviève Loanic (1971-1979), and to Debora Caprioglio (1987-1989). His three children Pola Kinski (1952), Nastassja Kinski (1961) and Nikolai Kinski (1976) are all actors. In 2006 Christian David published the first comprehensive biography based on newly discovered archived material, personal letters and interviews with Kinski's friends and colleagues.

Small German collectors card.

Trailer for Il grande silenzio/The Great Silence (Sergio Corbucci, 1968). Dource: Danios12345 (YouTube).

Trailer for Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht/Nosferatu the Vampyre (Werner Herzog, 1979). Source: Danios12345 (YouTube).

Long scene from Mein liebster Feind - Klaus Kinski/Kinski, My Best Fiend (Werner Herzog, 1999) with a raging Kinski during the shooting of Fitzcarraldo (1982). Source: Baranowski (YouTube).

Sources: Dan Schneider (Alt Film Guide), (IMDb), Hal Erickson (AllMovie), Karl Williams (AllMovie), Encyclopaedia Britannica, Filmportal.de, Wikipedia and .

Published on July 01, 2023 22:00

June 30, 2023

One Hundred Years Ago: Films Albatros

Oliver Hanley curates the One Hundred Years Ago section at Il Cinema Ritrovato this year. He explores the rich and varied history of the cinema in 1923 and selected classics, archival rarities and thought-provoking documentaries from 1923. In Hollywood, the Western became a serious genre in Hollywood, in Germany, the expressionist cinema reached its pinnacle and in Italy, the final Diva films were made. In this post, EFSP focuses on France where the exiled Russian filmmakers started to work at the studio Films Albatros in a suburb of Paris and produced several highlights of the European silent cinema.

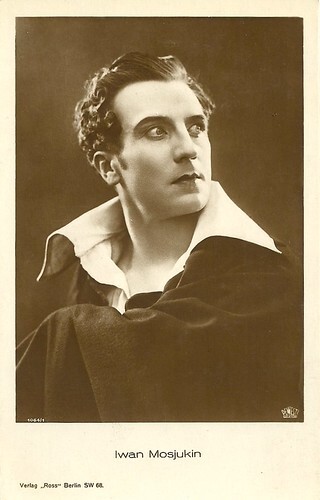

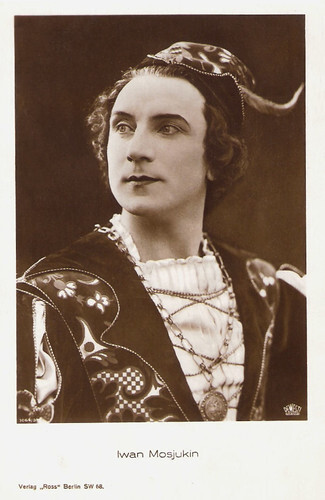

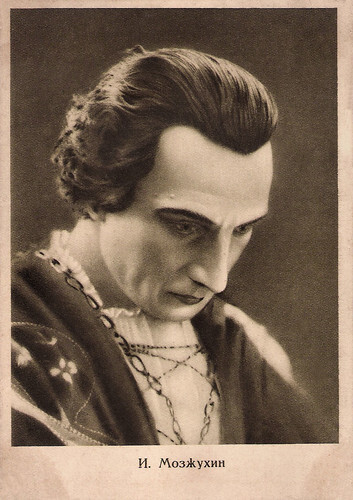

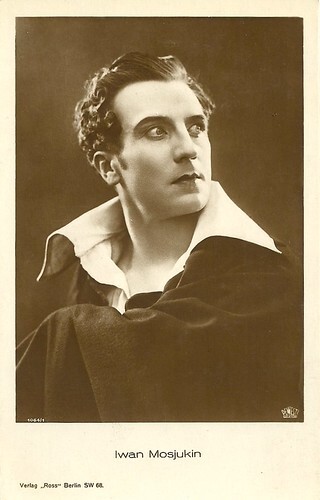

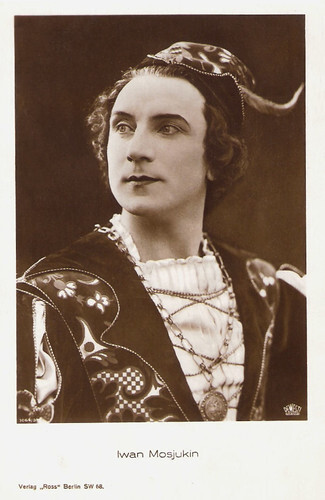

German postcard by Ross Verlag. no. 1064/1. Photo: DeWesti Film-Verleih. Ivan Mozzhukhin in Kean/Edmund Kean: Prince Among Lovers (Alexandre Volkoff, 1924).

Romanian postcard. Nathalie Kovanko in Le chant de l'amour triomphant/The song of triumphant love (Viktor Tourjansky, 1923).

French postcard. Nicolas Rimsky probably in the Albatros producton Calvaire d'amour (Viktor Tourjansky, 1923).

French postcard, with names written in Russian. Nathalie Lissenko , Nicolas Koline and Nicolas Rimsky in the Albatros producton Calvaire d'amour (Viktor Tourjansky, 1923).

French postcard by Cinémagazine no. 169. Ivan Mozzhukhin played the male lead of Prince Roundghito-Sing in the Albatross production Le lion des Mogols/The Lion of the Moguls (Jean Epstein, 1924). While the Moghol empire is falling apart, Prince Roundghito-Sing decides to leave and make films in Paris, where he falls for the attractions of the city.

Upright in the storm

Films Albatros was a French film production company established in 1922. It was formed by a group of White Russian exiles who had been forced to flee following the 1917 Russian Revolution and subsequent Russian Civil War. Initially, the firm's personnel consisted mainly of Russian exiles, but over time French actors and directors were employed by the company too. Its operations continued until the late 1930s. Faced with increasingly difficult working conditions in Russia after the revolution of 1917, the film producer Joseph Ermolieff decided to move his operations to Paris where he had connections with the Pathé company.

Arriving in 1920 with a group of close associates, Ermolieff took over a studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois in the eastern suburbs of Paris and began making films through his company Ermolieff-Cinéma. His co-founder of the company was Alexandre Kamenka, another Russian exile. In 1922 Ermolieff moved to Germany. Kamenka and his colleagues Noë Bloch and Maurice Hache decided to take over the company. They re-established it as the Société des Films Albatros. Kamenka also set up a distribution company called Les Films Armor in order to control the distribution of his own films. Various explanations have been given for the choice of the name Albatros. Was it the name of a boat which brought some of the émigrés from Russia? Was it a symbol of White Russia? Did an incident with an albatross happen on the journey? As well as adopting the image of the albatross as its symbol, the company took the motto 'Debout dans la tempête' (Upright in the storm).

Among the group of Russian artists who stayed to work with Albatros were the directors Victor Tourjansky and Alexandre Volkoff, the art director Alexandre Lochakoff, the costume designer Boris Bilinsky, and the actors Ivan Mozzhukhin (in French Ivan Mosjoukine and in German Iwan Mosjukin), Nathalie Lissenko , Nicolas Koline , and Nicolas Rimsky . Although this Russian company initially favoured Russian themes, Kamenka quickly realised the need for greater integration with French film production, and they turned increasingly to French subjects. In 1924 a number of Kamenka's Russian associates left Albatros, and Kamenka offered opportunities to several innovative French filmmakers including Jean Epstein, Jacques Feyder, Marcel L'Herbier and René Clair.

Kamenka's production policy combined prestige projects with openly commercial films, and his consistent record made him the most successful French producer during the 1920s, according to Charles Spaak, who came to the company as a scriptwriter in 1928. Kamenka successfully achieved international distribution for many of his films - even in Soviet Russia with which his company had so little political sympathy. From 1927, he entered into co-production arrangements with production companies in other European countries, driven by growing financial difficulties in the French film industry.

The arrival of sound pictures posed a serious difficulty for Albatros which had hitherto relied considerably upon Russian actors, especially Mozzhukhin whose accent precluded a successful transition into the talking era. The company's output diminished in the 1930s, but it achieved one further artistic success of note when Jean Renoir joined them for his adaptation of Maxim Gorky's Les Bas-fonds/The Lower Depths (1936). By this time, Albatros was the longest surviving film company operating in France, but with the outbreak of World War II, Kamenka wound up the company which had remained particularly associated with silent cinema.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 1064/3, 1927-1928. Photo: DeWesti Film-Verleih. Ivan Mozzhukhin in the Albatros production Kean (Alexandre Volkoff, 1924).

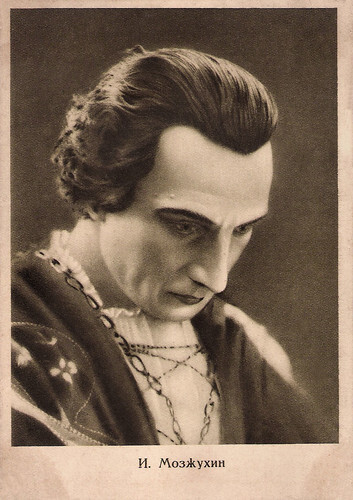

Russian postcard by Goznak, Moscow, Serie no. 5, no. A 4711, 1928. The card was issued in an edition of 25.000 copies. The price was 10 Kop. Photo: Ivan Mozzhukhin in Kean/Edmund Kean: Prince Among Lovers (Alexandre Volkoff, 1924).

French postcard by Cinémagazine Editions, no. 231. Photo: Nathalie Lissenko in Kean/Edmund Kean (Alexandre Volkoff a.k.a. Alexander Volkov, 1924).

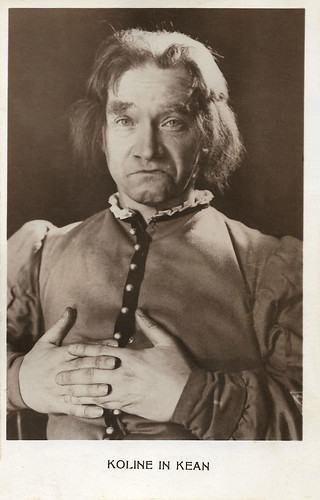

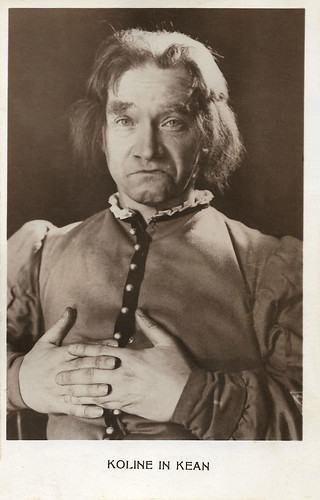

German postcard. Photo: Nicolas Koline in Kean/Edmund Kean: Prince Among Lovers (Alexandre Volkoff a.k.a. Alexander Volkov, 1924).

Belgian postcard. Nathalie Kovanko and Nicolas Koline in the Albatros production La dame masquée (Viktor Tourjansky 1924).

French postcard. Jaque Catelain and Nathalie Kovanko in Le prince charmant/Prince Charming (Viktor Tourjansky, 1925).

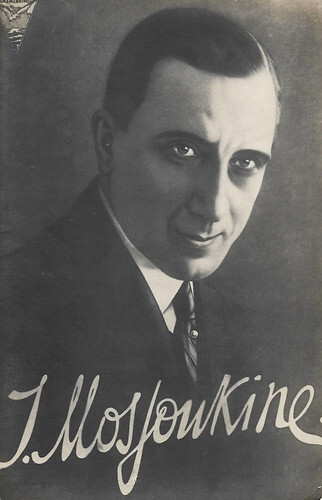

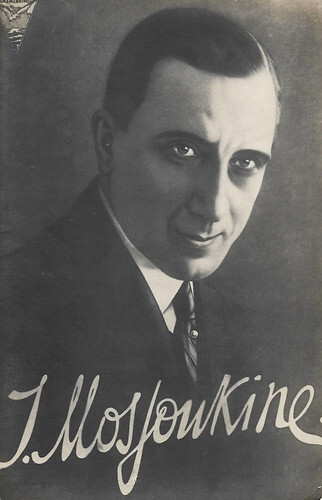

French or Romanian postcard. Photo: Albatros Films. Ivan Mozzhukhin .

French postcard by Cinémagazine Editions, no. 135. Nicolas Koline .

French postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 318. Nicolas Rimsky.

French postcard in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series by A.N., Paris, no. 89. Photo: Film Albatros. Ivan Mozzhukhin .

Sources: Il Cinema Ritrovato, Wikipedia (English and French) and .

German postcard by Ross Verlag. no. 1064/1. Photo: DeWesti Film-Verleih. Ivan Mozzhukhin in Kean/Edmund Kean: Prince Among Lovers (Alexandre Volkoff, 1924).

Romanian postcard. Nathalie Kovanko in Le chant de l'amour triomphant/The song of triumphant love (Viktor Tourjansky, 1923).

French postcard. Nicolas Rimsky probably in the Albatros producton Calvaire d'amour (Viktor Tourjansky, 1923).

French postcard, with names written in Russian. Nathalie Lissenko , Nicolas Koline and Nicolas Rimsky in the Albatros producton Calvaire d'amour (Viktor Tourjansky, 1923).

French postcard by Cinémagazine no. 169. Ivan Mozzhukhin played the male lead of Prince Roundghito-Sing in the Albatross production Le lion des Mogols/The Lion of the Moguls (Jean Epstein, 1924). While the Moghol empire is falling apart, Prince Roundghito-Sing decides to leave and make films in Paris, where he falls for the attractions of the city.

Upright in the storm

Films Albatros was a French film production company established in 1922. It was formed by a group of White Russian exiles who had been forced to flee following the 1917 Russian Revolution and subsequent Russian Civil War. Initially, the firm's personnel consisted mainly of Russian exiles, but over time French actors and directors were employed by the company too. Its operations continued until the late 1930s. Faced with increasingly difficult working conditions in Russia after the revolution of 1917, the film producer Joseph Ermolieff decided to move his operations to Paris where he had connections with the Pathé company.

Arriving in 1920 with a group of close associates, Ermolieff took over a studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois in the eastern suburbs of Paris and began making films through his company Ermolieff-Cinéma. His co-founder of the company was Alexandre Kamenka, another Russian exile. In 1922 Ermolieff moved to Germany. Kamenka and his colleagues Noë Bloch and Maurice Hache decided to take over the company. They re-established it as the Société des Films Albatros. Kamenka also set up a distribution company called Les Films Armor in order to control the distribution of his own films. Various explanations have been given for the choice of the name Albatros. Was it the name of a boat which brought some of the émigrés from Russia? Was it a symbol of White Russia? Did an incident with an albatross happen on the journey? As well as adopting the image of the albatross as its symbol, the company took the motto 'Debout dans la tempête' (Upright in the storm).

Among the group of Russian artists who stayed to work with Albatros were the directors Victor Tourjansky and Alexandre Volkoff, the art director Alexandre Lochakoff, the costume designer Boris Bilinsky, and the actors Ivan Mozzhukhin (in French Ivan Mosjoukine and in German Iwan Mosjukin), Nathalie Lissenko , Nicolas Koline , and Nicolas Rimsky . Although this Russian company initially favoured Russian themes, Kamenka quickly realised the need for greater integration with French film production, and they turned increasingly to French subjects. In 1924 a number of Kamenka's Russian associates left Albatros, and Kamenka offered opportunities to several innovative French filmmakers including Jean Epstein, Jacques Feyder, Marcel L'Herbier and René Clair.

Kamenka's production policy combined prestige projects with openly commercial films, and his consistent record made him the most successful French producer during the 1920s, according to Charles Spaak, who came to the company as a scriptwriter in 1928. Kamenka successfully achieved international distribution for many of his films - even in Soviet Russia with which his company had so little political sympathy. From 1927, he entered into co-production arrangements with production companies in other European countries, driven by growing financial difficulties in the French film industry.

The arrival of sound pictures posed a serious difficulty for Albatros which had hitherto relied considerably upon Russian actors, especially Mozzhukhin whose accent precluded a successful transition into the talking era. The company's output diminished in the 1930s, but it achieved one further artistic success of note when Jean Renoir joined them for his adaptation of Maxim Gorky's Les Bas-fonds/The Lower Depths (1936). By this time, Albatros was the longest surviving film company operating in France, but with the outbreak of World War II, Kamenka wound up the company which had remained particularly associated with silent cinema.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 1064/3, 1927-1928. Photo: DeWesti Film-Verleih. Ivan Mozzhukhin in the Albatros production Kean (Alexandre Volkoff, 1924).

Russian postcard by Goznak, Moscow, Serie no. 5, no. A 4711, 1928. The card was issued in an edition of 25.000 copies. The price was 10 Kop. Photo: Ivan Mozzhukhin in Kean/Edmund Kean: Prince Among Lovers (Alexandre Volkoff, 1924).

French postcard by Cinémagazine Editions, no. 231. Photo: Nathalie Lissenko in Kean/Edmund Kean (Alexandre Volkoff a.k.a. Alexander Volkov, 1924).

German postcard. Photo: Nicolas Koline in Kean/Edmund Kean: Prince Among Lovers (Alexandre Volkoff a.k.a. Alexander Volkov, 1924).

Belgian postcard. Nathalie Kovanko and Nicolas Koline in the Albatros production La dame masquée (Viktor Tourjansky 1924).

French postcard. Jaque Catelain and Nathalie Kovanko in Le prince charmant/Prince Charming (Viktor Tourjansky, 1925).

French or Romanian postcard. Photo: Albatros Films. Ivan Mozzhukhin .

French postcard by Cinémagazine Editions, no. 135. Nicolas Koline .

French postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 318. Nicolas Rimsky.

French postcard in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series by A.N., Paris, no. 89. Photo: Film Albatros. Ivan Mozzhukhin .

Sources: Il Cinema Ritrovato, Wikipedia (English and French) and .

Published on June 30, 2023 22:00

June 29, 2023

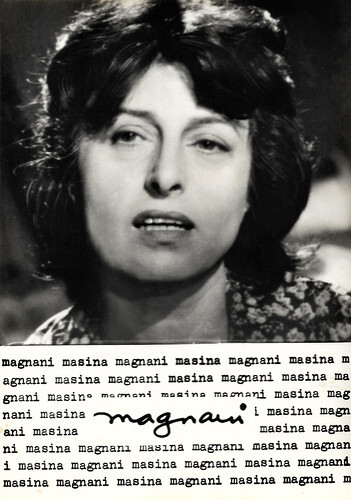

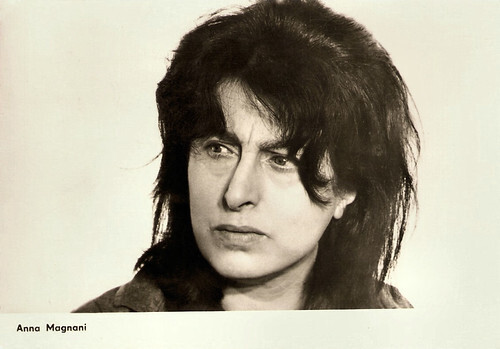

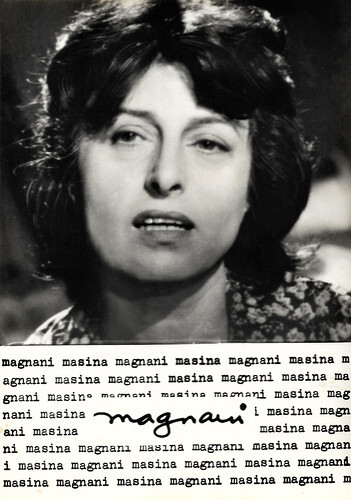

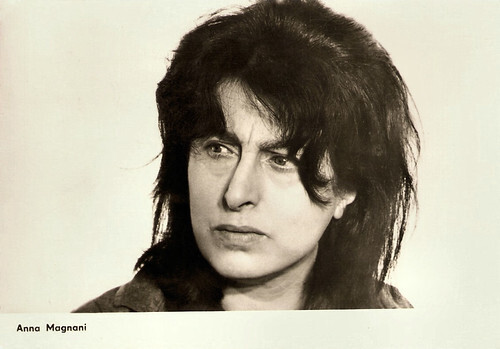

Anna Magnani

Perhaps the greatest, certainly the most admired and imitated – not only was Anna Magnani unique, but she was also a model of acting style and an Italian icon. At Il Cinema Ritrovato 2023, Emiliano Morreale curated 'Anna Magnani, the One and Only'. After first presenting herself as a brilliant actress – thanks to the triumph of Rome, Open City – she subsequently diversified from the many incarnations of her popular Roman character to play very different roles, such as those in Jean Renoir’s The Golden Coach or the monodrama The Human Voice (an episode in Roberto Rossellini’s L’Amore), to finally arriving in Hollywood and winning an Oscar for The Rose Tattoo. Her image was somewhat eccentric, amid the glamour of the 1950s and her golden moment lasted just over ten years, but an actress such as Magnani is unimaginable today. The legacy and unattainable model of Anna Magnani continue to inspire actresses in Italy and beyond.

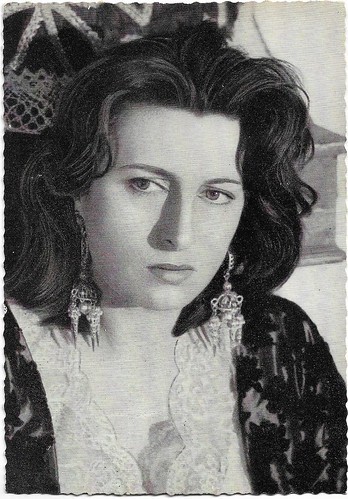

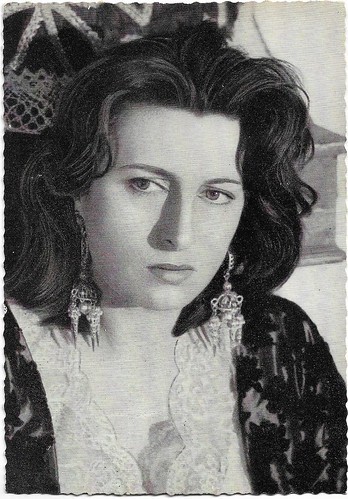

Italian postcard by Bromofoto, Milano, no. 1504. Photo: Paramount.

West German postcard by F.J. Rüdel, Filmpostkartenverlag, Hamburg-Bergedorf, no. 291. Photo: Consortial-Film. Anna Magnani in Assunta Spina (Mario Mattoli, 1948). In Germany, the film was titled Die Gezeichnete.

French postcard by Editions P.I., Paris, no. 386.

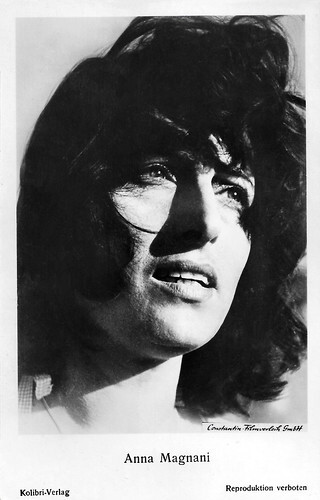

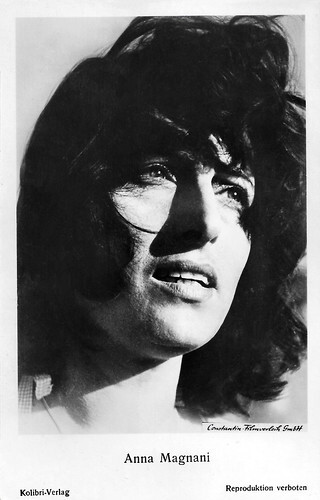

West-German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag. Photo: Constantin Film-Verleih GmbH. Anna Magnani in Vulcano (William Dieterle, 1950).

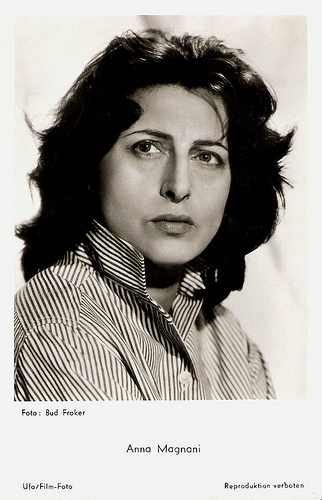

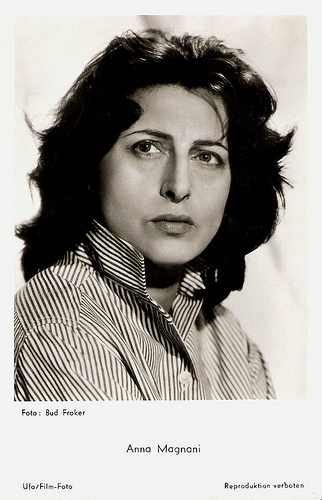

German postcard by Ufa, Berlin-Tempelhof, no. FK 4136. Photo: Bud Fraker. Anna Magnani in The Rose Tattoo (Daniel Mann, 1955).

The Italian Edith Piaf

Anna Magnani was born in Rome in 1908. She was the illegitimate child of Marina Magnani and an unknown father, whom Anna herself claimed was from the Calabria region of Italy (according to Wikipedia he was called Francesco Del Duce). She was raised by her maternal grandmother in a slum district of Rome after her mother left her.

At 14, she enrolled in a French convent school in Rome, where, she learned to speak French and play piano. She also developed a passion for acting from watching the nuns stage their Christmas play. At age 17, she went on to study at Santa Cecilia's Corso Eleanora Duse (the Eleanora Duse Royal Academy of Dramatic Art) in Rome. To support herself, Magnani sang bawdy Roman songs in nightclubs and cabarets leading to her being dubbed ‘the Italian Edith Piaf’.

She began touring the countryside with small repertory companies and had a small role in the silent film Scampolo (Augusto Genina, 1928) starring Carmen Boni . In 1933 she was acting in experimental plays in Rome when she was discovered by Italian filmmaker Goffredo Alessandrini. She played in La Cieca di Sorrento/The Blind Woman of Sorrento (Nunzio Malasomma, 1934). They married in 1933, shortly before the film was released. Magnani retired from full-time acting to devote herself exclusively to her husband, although she continued to play smaller film parts.

Under Alessandrini, she next appeared in Cavalleria/Cavalry (Goffredo Alessandrini, 1936) with Amedeo Nazzari , followed by La Principessa Tarakanova/Betrayal (Fyodor Otsep, Mario Soldati, 1938) featuring Annie Vernay . Alessandrini and Magnani separated in 1942 and finally divorced in 1950. After their separation her son Luca was born, the result of a brief affair with Italian matinée idol Massimo Serato. Magnani's life was struck by tragedy when Luca came down with crippling polio at only 18 months of age. He never regained the use of his legs. As a result, she spent most of her early earnings on specialists and hospitals.

In 1941, Magnani played the second female lead in the comedy of errors Teresa Venerdì/Do You Like Women (Vittorio De Sica, 1941) which writer-director Vittorio De Sica called Magnani’s ‘first true film’. In it, she plays Loletta Prima, the girlfriend of Di Sica’s character, Pietro Vignali. But her international breakthrough role had still to come.

German postcard by FBZ, no. 394. Photo: Cfilm. Anna Magnani in Assunta Spina (Mario Mattoli, 1948).

Italian postcard by Bromofoto, Milano, no. 104. Photo: Lux Film, Rome.

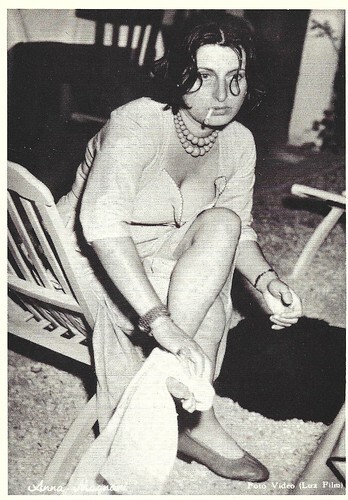

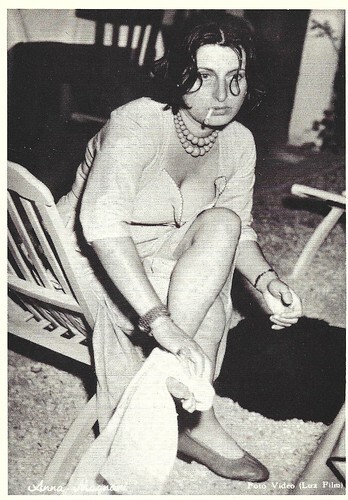

Vintage postcard in the Moviestar series. Photo: Video (Lux Film).

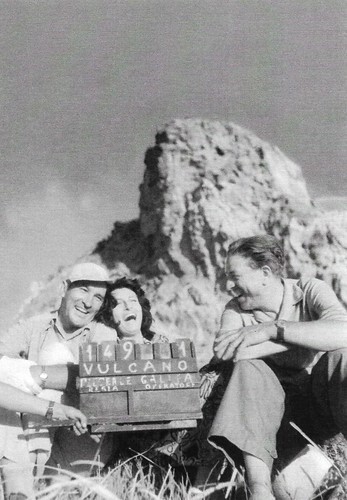

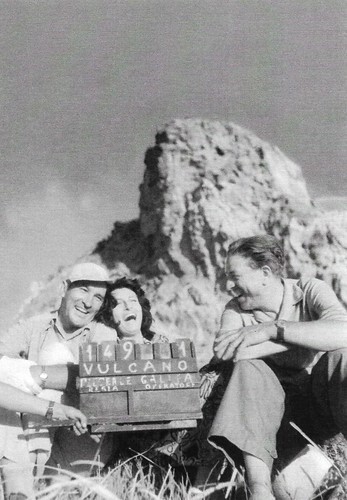

Vintage postcard by Liceo Artistico statale di Venezia / Panaria Film. Photo by Fosco Maraini. Anna Magnani and director William Dieterle in between the takes of the Italian film Vulcano (William Dieterle, 1950), shot in 1949. The man on the right could be producer Renzo Avanzo. The card was released by Panaria Film on the occasion of the preservation of the film in 2007.

Italian postcard by Liceo Artistico statale di Venezia, 2007. Photo: Fosco Maraini. Anna Magnani in Vulcano (William Dieterle, 1950). Caption: Anna Magnani, with the island of Vulcano in the background.

One of cinema's most devastating moments

Anna Magnani’s film career had spread over 18 years before she gained international renown as Pina in the neorealist milestone Roma, città aperta/Rome, Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945) about the final days of the Nazi occupation of Rome.

Magnani gave a brilliant performance as a woman who dies fighting to protect her husband, an underground fighter against the Nazis. Her harrowing death scene remains one of cinema's most devastating moments.

It established her as a star, although she lacked the conventional beauty and glamour often associated with the term. Slightly plump and rather short in stature with a face framed by unkempt raven hair and eyes encircled by deep, dark shadows, she smouldered with seething earthiness and volcanic temperament.

Roberto Rossellini was her lover at the time, and she collaborated with him on other films, including L'Amore/Love (Roberto Rossellini, 1948) a two-part film including Il miracolo/The Miracle and Una voce umana/The Human Voice. In the former, she played a pregnant outcast peasant who was seduced by a stranger and comes to believe the child she subsequently carries is Christ. Magnani plumbs both the sorrow and the righteousness of being alone in the world. The latter film is based on Jean Cocteau 's play about a woman desperately trying to salvage a relationship over the telephone. It is remarkable for the ways in which Magnani's powerful moments of silence segue into cries of despair.

Rossellini promised to direct her again in Stromboli, the next film he was preparing. However, when the screenplay was completed, he gave the role to Ingrid Bergman . This and his affair with the Swedish Hollywood star caused Magnani's breakup with Rossellini. As a result, she took on the starring role of Volcano/Vulcano (William Dieterle, 1949) with Rossano Brazzi , which was deliberately produced to invite comparison.

Italian postcard Marsilio Edizioni di Bianco & Nero. Photo: Paul Ronald. Anna Magnani in Bellissima (Luchino Visconti, 1951).

Reproduction of press photo. Photo: Paul Ronald. Anna Magnani in Bellissima (Luchino Visconti, 1951).

German film card by Filmbilder-Filmvertrieb Ernst Freihoff, Essen, no. 100. Photo: Dial / Unitalia Film. Anna Magnani as Camilla in the comedy La carrozza d'oro/ La carrosse d'or/The Golden Coach (Jean Renoir, 1952).

Italian postcard, no. 195. In 1957, Anna Magnani received the Nastri d'Argento (Silver Ribbon) award for Best Actress in a Leading Role for the film Suor Letizia/When Angels Don't Fly (Mario Camerini, 1956).

Italian postcard by Bromostampa, Milano, no. 110.

Prostitutes and suffering mothers

In 1950, Life magazine stated that Anna Magnani was "one of the most impressive actresses since Garbo." In Bellissima (Luchino Visconti, 1951) she played Maddalena, a blustery, obstinate stage mother who drags her daughter to Cinecittà for the 'Prettiest Girl in Rome' contest, with dreams that her plain daughter will be a star. Her emotions in the film went from those of rage and humiliation to maternal love. She later starred as Camille, a commedia dell'arte actress torn between three men, a soldier, a bullfighter, and a viceroy, in Le Carrosse d'or/The Golden Coach (Jean Renoir, 1953).

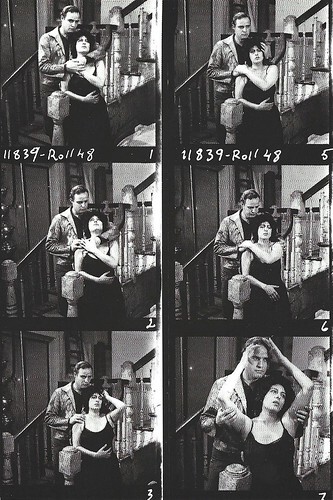

In Hollywood, she starred opposite Burt Lancaster as Serafina, the widowed mother of a teenage daughter in The Rose Tattoo (Daniel Mann, 1955). Screenwriter and close friend Tennessee Williams based the character of Serafina on Magnani. He even stipulated that the film must star Magnani. It was Magnani's first English-speaking role in a mainstream Hollywood movie, winning her the Academy Award, the BAFTA, the Golden Globe and the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actress. Magnani worked with Tennessee Williams again on The Fugitive Kind (Sidney Lumet, 1959), co-starring with Marlon Brando . In Hollywood she also appeared in Wild is the Wind (George Cukor, 1957), for which she was again nominated for the Academy Award.

In Italy, she played strong-willed prostitutes and suffering mothers in such films as the women-in-prison drama Nella città l'inferno/The Wild, Wild Women (Renato Castellani, 1958) with Giulietta Masina , and Mamma Roma (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1962). In Mama Roma Magnani is both the mother and the whore, playing an irrepressible prostitute determined to give her teenage son a respectable middle-class life. It was controversial but also one of Magnani's most critically acclaimed films.

In this later period of her career, she also appeared on Italian television and acted on the stage, most notably in 1965 when she starred in 'La Lupa' (She-Wolf), directed by Franco Zeffirelli, and in 1966 when she played the lead in Jean Anouilh's 'Medea', directed by Gian Carlo Menotti. In the film comedy The Secret of Santa Vittoria (Stanley Kramer, 1969), she co-starred with Anthony Quinn as a fighting husband and wife. Magnani and Quinn did also feud in private and their animosity spilled over into their scenes. Reportedly she bit Quinn in the neck and kicked him so hard that she broke a bone in her right foot. Her final screen performance was a cameo in Fellini's Roma (Federico Fellini, 1972).

In 1973, Anna Magnani died at the age of 65 in Rome, after a long battle with pancreatic cancer. Her son Luca and her favourite director Roberto Rossellini were at her bedside. With Rossellini, she'd patched up her disagreements some years before. It was reported that an enormous crowd turned out for her funeral in Italy, in a final public salute that is more typically reserved for Popes.

Italian postcard La Rotografica Romana. Photo: Anna Magnani in Nella città l'inferno/Caged (Renato Castellani, 1959).

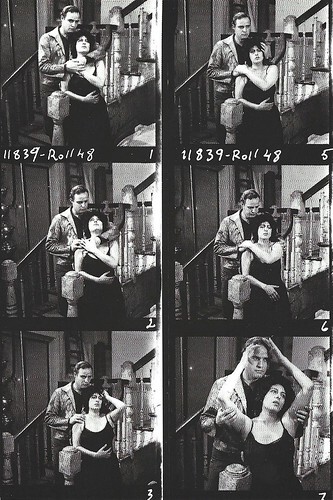

Vintage postcard by News Productions, Switzerland/Germany/UK. Photos: Sam Shaw. Anna Magnani and Marlon Brando in The Fugitive Kind (Sidney Lumet, 1960).

Czech collectors card by Pressfoto, Praha (Prague), no. S 37/2, 1964. Anna Magnani in Risate de Gioia/The Passionate Thief (Mario Monicelli, 1960).

East-German postcard by VEB Progress Film-Vertrieb, Berlin, no. 2823, 1967. Sent by mail in East Germany in 1974. Anna Magnani in Mamma Roma (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1962).

Scene from The Rose Tattoo (1953). Source: The SuppActress (YouTube).

Anna Magnani sings Scapricciatiello in Wild is the Wind (1957). Source: Minuit (YouTube).

Sources: Il Cinema Ritrovato 2023, Jason Ankeny (All Movie), (IMDb), Answers.com, Wikipedia and .

Italian postcard by Bromofoto, Milano, no. 1504. Photo: Paramount.

West German postcard by F.J. Rüdel, Filmpostkartenverlag, Hamburg-Bergedorf, no. 291. Photo: Consortial-Film. Anna Magnani in Assunta Spina (Mario Mattoli, 1948). In Germany, the film was titled Die Gezeichnete.

French postcard by Editions P.I., Paris, no. 386.

West-German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag. Photo: Constantin Film-Verleih GmbH. Anna Magnani in Vulcano (William Dieterle, 1950).

German postcard by Ufa, Berlin-Tempelhof, no. FK 4136. Photo: Bud Fraker. Anna Magnani in The Rose Tattoo (Daniel Mann, 1955).

The Italian Edith Piaf

Anna Magnani was born in Rome in 1908. She was the illegitimate child of Marina Magnani and an unknown father, whom Anna herself claimed was from the Calabria region of Italy (according to Wikipedia he was called Francesco Del Duce). She was raised by her maternal grandmother in a slum district of Rome after her mother left her.

At 14, she enrolled in a French convent school in Rome, where, she learned to speak French and play piano. She also developed a passion for acting from watching the nuns stage their Christmas play. At age 17, she went on to study at Santa Cecilia's Corso Eleanora Duse (the Eleanora Duse Royal Academy of Dramatic Art) in Rome. To support herself, Magnani sang bawdy Roman songs in nightclubs and cabarets leading to her being dubbed ‘the Italian Edith Piaf’.

She began touring the countryside with small repertory companies and had a small role in the silent film Scampolo (Augusto Genina, 1928) starring Carmen Boni . In 1933 she was acting in experimental plays in Rome when she was discovered by Italian filmmaker Goffredo Alessandrini. She played in La Cieca di Sorrento/The Blind Woman of Sorrento (Nunzio Malasomma, 1934). They married in 1933, shortly before the film was released. Magnani retired from full-time acting to devote herself exclusively to her husband, although she continued to play smaller film parts.

Under Alessandrini, she next appeared in Cavalleria/Cavalry (Goffredo Alessandrini, 1936) with Amedeo Nazzari , followed by La Principessa Tarakanova/Betrayal (Fyodor Otsep, Mario Soldati, 1938) featuring Annie Vernay . Alessandrini and Magnani separated in 1942 and finally divorced in 1950. After their separation her son Luca was born, the result of a brief affair with Italian matinée idol Massimo Serato. Magnani's life was struck by tragedy when Luca came down with crippling polio at only 18 months of age. He never regained the use of his legs. As a result, she spent most of her early earnings on specialists and hospitals.

In 1941, Magnani played the second female lead in the comedy of errors Teresa Venerdì/Do You Like Women (Vittorio De Sica, 1941) which writer-director Vittorio De Sica called Magnani’s ‘first true film’. In it, she plays Loletta Prima, the girlfriend of Di Sica’s character, Pietro Vignali. But her international breakthrough role had still to come.

German postcard by FBZ, no. 394. Photo: Cfilm. Anna Magnani in Assunta Spina (Mario Mattoli, 1948).

Italian postcard by Bromofoto, Milano, no. 104. Photo: Lux Film, Rome.

Vintage postcard in the Moviestar series. Photo: Video (Lux Film).

Vintage postcard by Liceo Artistico statale di Venezia / Panaria Film. Photo by Fosco Maraini. Anna Magnani and director William Dieterle in between the takes of the Italian film Vulcano (William Dieterle, 1950), shot in 1949. The man on the right could be producer Renzo Avanzo. The card was released by Panaria Film on the occasion of the preservation of the film in 2007.

Italian postcard by Liceo Artistico statale di Venezia, 2007. Photo: Fosco Maraini. Anna Magnani in Vulcano (William Dieterle, 1950). Caption: Anna Magnani, with the island of Vulcano in the background.

One of cinema's most devastating moments

Anna Magnani’s film career had spread over 18 years before she gained international renown as Pina in the neorealist milestone Roma, città aperta/Rome, Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945) about the final days of the Nazi occupation of Rome.

Magnani gave a brilliant performance as a woman who dies fighting to protect her husband, an underground fighter against the Nazis. Her harrowing death scene remains one of cinema's most devastating moments.

It established her as a star, although she lacked the conventional beauty and glamour often associated with the term. Slightly plump and rather short in stature with a face framed by unkempt raven hair and eyes encircled by deep, dark shadows, she smouldered with seething earthiness and volcanic temperament.

Roberto Rossellini was her lover at the time, and she collaborated with him on other films, including L'Amore/Love (Roberto Rossellini, 1948) a two-part film including Il miracolo/The Miracle and Una voce umana/The Human Voice. In the former, she played a pregnant outcast peasant who was seduced by a stranger and comes to believe the child she subsequently carries is Christ. Magnani plumbs both the sorrow and the righteousness of being alone in the world. The latter film is based on Jean Cocteau 's play about a woman desperately trying to salvage a relationship over the telephone. It is remarkable for the ways in which Magnani's powerful moments of silence segue into cries of despair.

Rossellini promised to direct her again in Stromboli, the next film he was preparing. However, when the screenplay was completed, he gave the role to Ingrid Bergman . This and his affair with the Swedish Hollywood star caused Magnani's breakup with Rossellini. As a result, she took on the starring role of Volcano/Vulcano (William Dieterle, 1949) with Rossano Brazzi , which was deliberately produced to invite comparison.

Italian postcard Marsilio Edizioni di Bianco & Nero. Photo: Paul Ronald. Anna Magnani in Bellissima (Luchino Visconti, 1951).

Reproduction of press photo. Photo: Paul Ronald. Anna Magnani in Bellissima (Luchino Visconti, 1951).

German film card by Filmbilder-Filmvertrieb Ernst Freihoff, Essen, no. 100. Photo: Dial / Unitalia Film. Anna Magnani as Camilla in the comedy La carrozza d'oro/ La carrosse d'or/The Golden Coach (Jean Renoir, 1952).

Italian postcard, no. 195. In 1957, Anna Magnani received the Nastri d'Argento (Silver Ribbon) award for Best Actress in a Leading Role for the film Suor Letizia/When Angels Don't Fly (Mario Camerini, 1956).

Italian postcard by Bromostampa, Milano, no. 110.

Prostitutes and suffering mothers

In 1950, Life magazine stated that Anna Magnani was "one of the most impressive actresses since Garbo." In Bellissima (Luchino Visconti, 1951) she played Maddalena, a blustery, obstinate stage mother who drags her daughter to Cinecittà for the 'Prettiest Girl in Rome' contest, with dreams that her plain daughter will be a star. Her emotions in the film went from those of rage and humiliation to maternal love. She later starred as Camille, a commedia dell'arte actress torn between three men, a soldier, a bullfighter, and a viceroy, in Le Carrosse d'or/The Golden Coach (Jean Renoir, 1953).

In Hollywood, she starred opposite Burt Lancaster as Serafina, the widowed mother of a teenage daughter in The Rose Tattoo (Daniel Mann, 1955). Screenwriter and close friend Tennessee Williams based the character of Serafina on Magnani. He even stipulated that the film must star Magnani. It was Magnani's first English-speaking role in a mainstream Hollywood movie, winning her the Academy Award, the BAFTA, the Golden Globe and the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actress. Magnani worked with Tennessee Williams again on The Fugitive Kind (Sidney Lumet, 1959), co-starring with Marlon Brando . In Hollywood she also appeared in Wild is the Wind (George Cukor, 1957), for which she was again nominated for the Academy Award.

In Italy, she played strong-willed prostitutes and suffering mothers in such films as the women-in-prison drama Nella città l'inferno/The Wild, Wild Women (Renato Castellani, 1958) with Giulietta Masina , and Mamma Roma (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1962). In Mama Roma Magnani is both the mother and the whore, playing an irrepressible prostitute determined to give her teenage son a respectable middle-class life. It was controversial but also one of Magnani's most critically acclaimed films.

In this later period of her career, she also appeared on Italian television and acted on the stage, most notably in 1965 when she starred in 'La Lupa' (She-Wolf), directed by Franco Zeffirelli, and in 1966 when she played the lead in Jean Anouilh's 'Medea', directed by Gian Carlo Menotti. In the film comedy The Secret of Santa Vittoria (Stanley Kramer, 1969), she co-starred with Anthony Quinn as a fighting husband and wife. Magnani and Quinn did also feud in private and their animosity spilled over into their scenes. Reportedly she bit Quinn in the neck and kicked him so hard that she broke a bone in her right foot. Her final screen performance was a cameo in Fellini's Roma (Federico Fellini, 1972).

In 1973, Anna Magnani died at the age of 65 in Rome, after a long battle with pancreatic cancer. Her son Luca and her favourite director Roberto Rossellini were at her bedside. With Rossellini, she'd patched up her disagreements some years before. It was reported that an enormous crowd turned out for her funeral in Italy, in a final public salute that is more typically reserved for Popes.

Italian postcard La Rotografica Romana. Photo: Anna Magnani in Nella città l'inferno/Caged (Renato Castellani, 1959).

Vintage postcard by News Productions, Switzerland/Germany/UK. Photos: Sam Shaw. Anna Magnani and Marlon Brando in The Fugitive Kind (Sidney Lumet, 1960).

Czech collectors card by Pressfoto, Praha (Prague), no. S 37/2, 1964. Anna Magnani in Risate de Gioia/The Passionate Thief (Mario Monicelli, 1960).

East-German postcard by VEB Progress Film-Vertrieb, Berlin, no. 2823, 1967. Sent by mail in East Germany in 1974. Anna Magnani in Mamma Roma (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1962).

Scene from The Rose Tattoo (1953). Source: The SuppActress (YouTube).

Anna Magnani sings Scapricciatiello in Wild is the Wind (1957). Source: Minuit (YouTube).

Sources: Il Cinema Ritrovato 2023, Jason Ankeny (All Movie), (IMDb), Answers.com, Wikipedia and .

Published on June 29, 2023 22:00

June 28, 2023

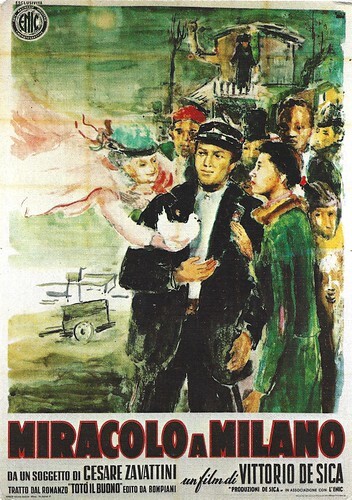

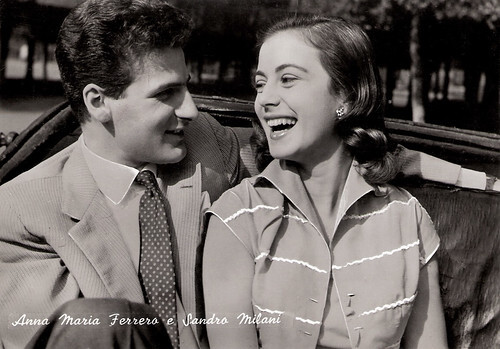

Tribute to Suso Cecchi d’Amico

Over the course of a career that began at the time of the birth of neorealism and lasted more than 60 years, Suso Cecchi d’Amico worked on the screenplays of more than 120 films (mainly, but not exclusively, Italian) directed by both newcomers and established directors. Il Cinema Ritrovato 2023 presents a tribute to her, curated by her children, Masolino, Silvia and Caterina d’Amico. Suso Cecchi d’Amico's aim was never to impose her own ideas but to understand and support the projects and poetics of the authors with whom she worked. On the other hand, like any artist, she clearly possessed her own voice and personality, which this section proposes to trace through films that are very different in tone, genre and language. It is certainly a partial but undoubtedly fascinating selection, presenting significant works chosen from a rich and heterogeneous filmography that few other screenwriters can boast. For this post, Ivo Blom selected a series of postcards and stills of her films and wrote the text for this post for which he used an interview he had with her in 2004.

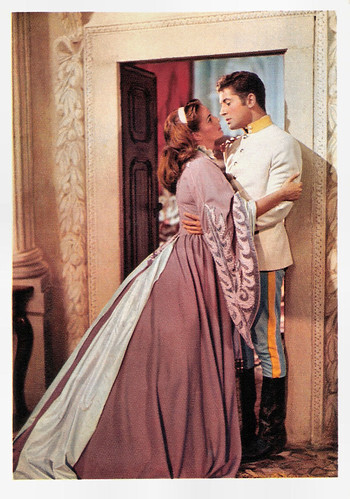

Italian postcard by Rotocalco Dagnino, Torino. Photo: Lux Film. Alida Valli as Countess Livia Serpieri and Farley Granger as Lt. Franz Mahler in Luchino Visconti's historical film Senso (1954).

German postcard. Photo Ufa. Sophia Loren in La fortuna di essere donna/What a Woman! (Alessandro Blasetti, 1956).

Publicity still used in Germany, distributed by Rank, the mark of the German censor FSK. Thomas Milian and Romy Schneider in Luchino Visconti 's episode Il Lavoro in the episode film Boccaccio 70 (1962).

First screenplay

Suso Cecchi D’Amico, pseudonym of Giovanna Cecchi D'Amico, was born in Rome in 1914 to Tuscan parents: the writer Emilio Cecchi (from whom she took her birth name Cecchi) and the painter Leonetta Pieraccini. After finishing the Lycée Chateaubriand in Rome, she did not enrol at university, as she had not taken a diploma in Latin and Greek. 'To continue my studies I could only enrol in one or two faculties, such as botany, which frankly did not interest me'. After a stay abroad, in Switzerland and England, she decided to get a job. Thanks to the intervention of Minister Giuseppe Bottai, "the only hierarch who had any relationship with intellectuals", she was hired at the Ministry of Corporations, later the Ministry of Trade and Currency, where she worked for almost seven years as personal secretary to Eugenio Anzilotti, Director General of Foreign Trade.

In 1938 she married musicologist Fedele D'Amico, Silvio's son, by whom she had three children: Masolino, Silvia and Caterina, who all later on would have important careers in Italian culture. Alone or together with her father, she performed many translations from English and French, including Thomas Hardy's 'Jude the Obscure', 'Tobacco Road', 'Life with Father', 'Look Homeward, Angel', William Shakespeare ’s 'The Merry Wives of Windsor' and 'Othello'. She abandoned this activity, in which she did not show the facility that her son Masolino would have when he began working for the cinema.

During the Second World War, while her husband, a member of the communist Catholics with Adriano Ossicini and Franco Rodano, led a clandestine life in Rome and directed the newspaper Voce Operaia, she moved for six to seven months to Poggibonsi, to the villa of her uncle Gaetano Pieraccini, a doctor and politician who would be the first mayor of Florence after the Liberation. At the end of the conflict, while her husband was hospitalised in Switzerland to recover from tuberculosis, she was "forced to scramble every which way to support herself, her first two children [...] and the house, populated by nannies and other women". Among the curious occupations of this period, she gave lessons in good manners to Maria Michi and English conversation to Giovanna Galletti, both of whom were actresses in Roberto Rossellini’s Roma città aperta/Rome Open City (1945).

Suso Cecchi D’Amico worked on her first screenplay, Avatar, a romantic story set in Venice, inspired by a story by Théophile Gautier, with Ennio Flaiano, Renato Castellani and Alberto Moravia, for Carlo Ponti, then not yet a major producer. But the project was abandoned before even arriving at a proper screenplay, Castellani alone completing a treatment. Together with Castellani, she worked on a story based on a subject by playwright Aldo De Benedetti, Mio figlio professore (1946), directed by Castellani himself and starring Aldo Fabrizi and the Nava sisters. Together with Piero Tellini, she wrote Vivere in pace (1947) and L'onorevole Angelina (1947), both directed by Luigi Zampa and starring Aldo Fabrizi and Anna Magnani respectively, with whom she began to associate assiduously, forging one of her rare friendships with actors. For the subject of Vivere in pace, also signed by Tellini and Zampa but essentially her own, she won the Nastro d'argento for the best subject.