Farran Smith Nehme's Blog, page 2

December 21, 2018

The Baker's Wife (1938) at Film Forum

Film Forum has a holiday present for New Yorkers starting today: A week-long run of Marcel Pagnol’s magical La Femme du Boulanger (The Baker’s Wife), from 1938. The Siren has seen the restoration that Film Forum is showing, and it is beautiful. The film probably hasn’t looked this good in decades. It definitely hasn’t been seen (legally—ahem) in this country for many a long year; rumor has it that there were disputes with the estate of Jean Giono, who wrote the story, "Blue Boy," that the movie is based on. Whatever was keeping The Baker’s Wife from screens, rejoice that it’s back with us.

The film stars Raimu, and your regard for it will undoubtedly stand or fall on your opinion of Raimu’s all-dominating performance. Arletty, Marlene Dietrich, and Orson Welles all said at one time or another that they considered Raimu the greatest actor in the world; the Siren adores him too. Here, Raimu plays the baker of the title, a man appropriately named Aimable, who has just set up shop in a tiny Provençal village, bringing them good bread at last after years of putting up with a man who couldn’t control the temperature of the oven. Aimable has a vastly younger and eye-poppingly sexy wife, Aurélie, played by Ginette Leclerc, and as my grandmother would have said, Aimable thinks Aurélie hung the moon. (Pagnol offered the part to Joan Crawford, which newly learned fact is the Siren’s “What If” of the year.) But the marriage is clearly sexless, and Aurélie is vulnerable to the he-man charms of a local shepherd (a smouldering Charles Moulin). She runs off with the shepherd, and the heartbroken Aimable takes to downing pastis instead of baking. The villagers, from the local marquis (Fernand Charpin) to the priest (Robert Vattier) to the schoolteacher (Robert Bassac) band together to bring back the baker’s wife.

It is an uncomplicated plot that unfolds at a leisurely 133 minutes; most Pagnol films take their time, as the filmmaker loved to give his characters as much time as needed for their full natures to be revealed. The villagers are flawed, selfish, at times bone-headed and even cruel, but our affection for these people grows as their regard for their grieving baker increases. The mission to bring back Aurélie starts as a necessary mission to get decent baguettes back on the table, but it ends as a gesture of pure devotion.

As for Raimu, his Aimable may be an even greater achievement than his César in the Marseilles trilogy. The actor brought a head-to-toe physicality to film, aided by Pagnol, who always knows exactly how much of Raimu to keep in frame. At times Aimable’s innocence verges on stupidity, such as when the shepherd comes to serenade Aurelie and the baker sees it as a charming local custom instead of appalling insolence. The baker’s drunk scene takes him from immobile self-pity to perilous lunging about the cafe, until the villagers steer him home like an ocean liner with a broken rudder. Yet throughout the movie, Raimu switches from funny to heartbreaking and back again to funny, as easily as one gets water from a tap.

The Siren has many readers who live far from New York, but they should take heart. Not only is the film likely to play a number of other repertory houses in big cities, but in the past Janus Films has opened restorations in preparation for a later Criterion release. Let us cross our fingers. In the meantime, the Siren wishes a very merry Christmas to all who celebrate. And may we all find films to give us a break from daily cares as 2018 winds to a close.

Published on December 21, 2018 07:45

December 19, 2018

2018: The Year in Siren Writing

This year has found the Siren doing most of her writing for paying outlets, which endeavors plus the demands of her brood have kept her largely off the blog. For those who haven’t been keeping up with the Siren’s writings, due to exhaustion, distraction, or because Max was polishing the Isotta Fraschini and forgot to turn on the computer, the Siren herewith presents an abridged list of what she was doing in 2018.

First on the list is something the Siren wrote for the Criterion Collection’s blog, The Current, on the exquisite and irreplaceable Danielle Darrieux. Alas, the very mention of that name brings the Siren to sad news about a friend who loved Darrieux above all others. This year, we lost one of the pillars of the Siren community: X. Trapnel, our own beloved XT, who died suddenly in the fall. He enriched the Siren’s life, and the blog would never have been the same without him. The Siren hopes he is somewhere meeting his beloved Mme. Darrieux at last.

First on the list is something the Siren wrote for the Criterion Collection’s blog, The Current, on the exquisite and irreplaceable Danielle Darrieux. Alas, the very mention of that name brings the Siren to sad news about a friend who loved Darrieux above all others. This year, we lost one of the pillars of the Siren community: X. Trapnel, our own beloved XT, who died suddenly in the fall. He enriched the Siren’s life, and the blog would never have been the same without him. The Siren hopes he is somewhere meeting his beloved Mme. Darrieux at last.By the time Darrieux was sixty-five, she had long since grown into an ineffable serenity and elegance, not just foreigners’ ideal of a Frenchwoman, but the French ideal as well. The first glimpse of her in Demy’s sung-through musical Une chambre en ville comes in black-and-white, like an echo of Darrieux’s past as well as the character’s. From the window of her spacious apartment an annoyed Madame Langlois is looking down on a worker’s demonstration. She can see her handsome young tenant, François Guilbaud (Richard Berry), in the front line facing down a vast army of police. Madame Langlois takes his presence among the strikers, as she takes many things, as a sign of terrible manners.

Not online: The Siren’s enthusiastic Sight & Sound review of

Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film

, by Alan K. Rode. If you need a last-minute Christmas gift for someone who loves classic film and/or Hollywood history, this would be an excellent choice — at more than 400 pages, it reads as swiftly and enjoyably as any biography the Siren has read, and she has read an inordinate number of such books, as her patient readers know.

Not online: The Siren’s enthusiastic Sight & Sound review of

Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film

, by Alan K. Rode. If you need a last-minute Christmas gift for someone who loves classic film and/or Hollywood history, this would be an excellent choice — at more than 400 pages, it reads as swiftly and enjoyably as any biography the Siren has read, and she has read an inordinate number of such books, as her patient readers know....Curtiz also “worked people to death,” remarked Wax Museum’s Glenda Farrell, who still liked the director, although many (perhaps even most) of his actors did not. Early on, Rode drily remarks that Curtiz, “more than any other studio director… was responsible for the founding of the Screen Actors Guild.” Curtiz thought lunch was for sissies and until groups like SAG began to pester him, the director appeared to think going home and sleeping were dispensable luxuries as well. By the time Curtiz’s career was in full flower, and he was beginning his 12-film association with Errol Flynn, the director had settled down a bit, but not much, and the easygoing Flynn grew to detest the man who unquestionably did the most to make him a star. So did Flynn’s frequent co-star Olivia de Havilland. Yet all his life, Curtiz maintained a great ability to spot talent (he was an early booster of both Doris Day and the great John Garfield, to name just two) and a knack for drawing out a great performance…

The booklet essay for Criterion’s Blu-Ray release of King of Jazz. In 1930, the daring and ill-fated Carl “Junior” Laemmle put his chips on two big projects. One you perhaps have heard of, a trifle called All Quiet on the Western Front. The other was this extravagant two-strip Technicolor revue, an attempt to make a movie star of the portly bandleader Paul Whiteman. (Includes bonus sideswipe of Mordaunt Hall.)

The booklet essay for Criterion’s Blu-Ray release of King of Jazz. In 1930, the daring and ill-fated Carl “Junior” Laemmle put his chips on two big projects. One you perhaps have heard of, a trifle called All Quiet on the Western Front. The other was this extravagant two-strip Technicolor revue, an attempt to make a movie star of the portly bandleader Paul Whiteman. (Includes bonus sideswipe of Mordaunt Hall.)In the end...production delays cost the movie more dearly than anyone could have foreseen. By the time King of Jazz made its bow, Hollywood had indulged its eternal tendency to run a trend into the ground, and revues were such a drug on the market that some other musicals were being advertised with taglines like “Positively not a revue!” There was also the little matter of what happened on Wall Street on October 29, 1929. The worst of the Great Depression was in the future, but the effects of the crash were already being felt.

The Museum of Modern Art showed a two-part series of splendid restorations of films from Republic Pictures, and the Siren wrote about them both for the late and very much lamented Village Voice.

The Museum of Modern Art showed a two-part series of splendid restorations of films from Republic Pictures, and the Siren wrote about them both for the late and very much lamented Village Voice.There was one way to get [legendarily cheap Republic studio boss Herbert] Yates to pry open his checkbook, however, and that was to put Vera Hruba Ralston in the leading role. Vera Hruba was a former Olympic ice skater with a lithe and athletic figure, a face the camera liked only intermittently, and a Czech accent that no amount of coaching could diminish. When Yates met his version of Citizen Kane’s Susan Alexander, a girl fully forty years his junior, he was married with two kids. He signed Ralston to a contract in 1943, and thereafter this otherwise hard-nosed and entirely unromantic man spent every last one of his remaining studio years engaged in a fruitless effort to make Ralston a star, meantime divorcing his wife in 1948 and marrying Vera in 1952. Yates gave Ralston — billed variously as Vera Hruba, Vera Ralston, and Vera Hruba Ralston — his best scriptwriters, directors, and co-stars. For years, according to Scott Eyman, Yates bought the full back-page ad space at Variety and the Hollywood Reporter just for the opportunity to run a photo of Ralston with the caption, “The World’s Most Beautiful Woman.” It was rather touching, as even Yates’s frustrated employees would sometimes admit, but it was all for naught.

Part two, or as the Siren likes to call it, Republic Rides Again:

Then there’s Fair Wind to Java (1953), described by at least one critic as “the ultimate B-picture” (and once you’ve seen it, that’s hard to dispute). Vera Hruba Ralston often cited Fair Wind as her favorite movie. The Czech former figure skater’s casting as a Balinese dancer named Kim Kim (“My father was white,” the character explains casually) is the strangest in the movie, which is saying something when you have Fred MacMurray as a hard-bitten sea captain named Boll… Scorsese has often spoken of his fondness for Fair Wind — and indeed, it is hugely enjoyable in its crazy way, graced by an eye-searing Trucolor palette, barreling plot developments, indifference to plausibility, and dialogue like “It’s a little island called Krakatoa. No one’s ever heard of it!”

Not online: An essay included in the British company Powerhouse's lavish Blu-Ray box set of Budd Boetticher films. The Siren notes, also for purposes of Christmas or other holiday giving or just plain old self-care, that this set is region-free. She wrote the essay for Comanche Station.

Not online: An essay included in the British company Powerhouse's lavish Blu-Ray box set of Budd Boetticher films. The Siren notes, also for purposes of Christmas or other holiday giving or just plain old self-care, that this set is region-free. She wrote the essay for Comanche Station.The lonely, high-up opening view of Randolph Scott on a horse, the only thing moving among the stones of the Alabama Hills, isn’t what establishes the valedictory mood of Comanche Station. No, it’s the slant of the sun. The light’s intensity has lessened and the shadows have lengthened. It’s late in the day— for the characters, for the series of movies Scott had made with director Budd Boetticher, for Scott’s career, for the classic Western itself.

Again for the Voice (lord, how the Siren misses it), an article tied to MoMA's big retrospective of the films of Emilio Fernández, a great Mexican director whose reputation in this country more than deserves to be revived.

Again for the Voice (lord, how the Siren misses it), an article tied to MoMA's big retrospective of the films of Emilio Fernández, a great Mexican director whose reputation in this country more than deserves to be revived.In an age when “colorful” was almost part of a director’s CV — from the eyepatches of Raoul Walsh and John Ford to the foreign birthplaces of Fritz Lang and Ernst Lubitsch to the itinerant macho-jobs years of William Wellman — Fernández went the extra mile. He pulled a stint in prison for his part in the failed rebellion, then drifted around the States, spending time (as he told it) as a cowboy in a circus, a salmon fisherman, a licensed pilot, a bartender, and, finally, as an extra in Hollywood, in the late Twenties. There, legend has it, Fernández’s friend, Dolores del Río, had him pose for her husband, the famed art director Cecil Beaton, for what became the Academy Award statuette. Though Fernández became stocky in his later years, one look at his naked torso in Janitzio — a 1935 movie in the series, in which he plays a star-crossed lover in a fishing village — offers pretty powerful evidence. He really does look like a walking Oscar.

A long and obsessively researched essay on the behind-the-scenes collaborators of Marlene Dietrich and Josef von Sternberg, for Criterion's epic six-disc release "Dietrich and von Sternberg in Hollywood." If you click on no other link in this here post, the Siren hopes you do click on this one, because for the first three months of 2018, she worked her tail feathers off on this one.

A long and obsessively researched essay on the behind-the-scenes collaborators of Marlene Dietrich and Josef von Sternberg, for Criterion's epic six-disc release "Dietrich and von Sternberg in Hollywood." If you click on no other link in this here post, the Siren hopes you do click on this one, because for the first three months of 2018, she worked her tail feathers off on this one.“I never had a better assistant than Miss Dietrich,” the director told one interviewer, with lordly assurance. Still, von Sternberg paid this assistant the tribute of immortality. Other “assistants” went unseen by audiences and are much less frequently discussed. The story of von Sternberg and his colleagues, especially those who never appeared on-screen—the ones who gave dialogue to his characters and shape to his plots, who constructed costumes and sets, the woman whose makeup perfected Dietrich and the men who then lit that glorious face—can be difficult to tease out in part because von Sternberg was almost pathologically incapable of sharing credit. All these artists would have agreed that a von Sternberg film revealed his vision, down to the items on a character’s dressing table and the way Dietrich’s cheekbones were highlighted. But, as Baxter writes, though the director “liked to say he ‘dictated’ the look of his films, dictation is not creation. He needed talented individuals to realize his conceptions.”

The magnificent Stéphane Audran died in March, and the Village Voice asked the Siren to write a tribute. (Who else will ever do that, now that the Voice is gone? Alas.)

The magnificent Stéphane Audran died in March, and the Village Voice asked the Siren to write a tribute. (Who else will ever do that, now that the Voice is gone? Alas.)If someone asked me to choose the ultimate in Stéphane Audran scenes — not her best or most emotive acting, but a sequence that summed up her talent, her presence — I would choose an early moment in Juste Avant la Nuit (Just Before Nightfall, 1971), directed by her then-husband Claude Chabrol. Her character, Hélène Masson, is in the kitchen of her family’s spectacular modern mansion, baking a chocolate cake with her daughter and the girl’s au pair. She is mixing the batter with a wooden spoon, holding it up from time to time to check whether it has reached the proper consistency. Her posture is erect and graceful as she walks around the room with her bowl, chatting and mixing. Hélène has no apron over her Karl Lagerfeld outfit. There is no need, as Hélène probably has not stained an outfit since her days in lycée. The hard work of baking has touched neither her hair nor her maquillage.

For the San Francisco Silent Film Festival's March shindig, an essay on The Saga of Gösta Berling, a movie the Siren had somehow never seen. She fell in love with it, to the point that she read the Selma Lagerlöf novel. (She recommends the translation by Pauline Bancroft Flach, and not the later Penguin one, which is afflicted by the modern mania for rendering prose as flat, affectless, and literal as possible.)

For the San Francisco Silent Film Festival's March shindig, an essay on The Saga of Gösta Berling, a movie the Siren had somehow never seen. She fell in love with it, to the point that she read the Selma Lagerlöf novel. (She recommends the translation by Pauline Bancroft Flach, and not the later Penguin one, which is afflicted by the modern mania for rendering prose as flat, affectless, and literal as possible.)...From a distance of almost a hundred years, it’s evident that Garbo—only eighteen years old and so beautiful it is said her close-ups made audiences gasp—is just one of many impressive things about Gösta Berling. As the story unfolds, the title’s ex-pastor, played by Lars Hanson, has been defrocked. Gösta’s preaching is so enthralling that his congregation is ready to forgive him for his latest drunken escapade, but then, spurred by idealism and a bridge-burning compulsion that gets him in trouble throughout, Gösta swings into a rousing condemnation of the parishioners’ own chronic boozing. His goose thus self-cooked, he sets out on the road.

The lovely folks at Criterion asked the Siren to write the booklet essay for one of her most favorite comedies, My Man Godfrey. Which is funny, because the Siren has spent much of the year reading the news and murmuring, "All I have to say is some people will be sorry someday." (Or, if occasion demands, "Life is but an empty bubble.")

The lovely folks at Criterion asked the Siren to write the booklet essay for one of her most favorite comedies, My Man Godfrey. Which is funny, because the Siren has spent much of the year reading the news and murmuring, "All I have to say is some people will be sorry someday." (Or, if occasion demands, "Life is but an empty bubble.")There were hilariously dysfunctional families in American film before and after My Man Godfrey, but the Bullocks of 1011 Fifth Avenue represent peak lunacy. There’s devious Cornelia, played by the darkly beautiful Gail Patrick—“a sweet-tempered little number,” as the maid, Molly (Jean Dixon), calls her. There’s mother Angelica (Alice Brady), whose hangovers include visions of pixies (“I don’t like them, but I don’t like to see them stepped on”), and who is sponsoring a “protégé,” Carlo (Mischa Auer). Carlo’s sponsored talents—the ones that could be shown under the Production Code, anyway—involve a lugubrious rendition of the Russian folk song “Ochi chyornye,” a remarkable ability to make food disappear, and the single best gorilla impression in the history of American film.

Riffing on a very short thing she once wrote for the blog, the Siren also contributed an essay to Criterion's lavish Blu-ray for The Magnificent Ambersons. The Siren was happy to have the opportunity to praise "The Voice of Orson Welles" at greater length.

Riffing on a very short thing she once wrote for the blog, the Siren also contributed an essay to Criterion's lavish Blu-ray for The Magnificent Ambersons. The Siren was happy to have the opportunity to praise "The Voice of Orson Welles" at greater length.Welles was marked from the beginning by his prodigal gifts, speaking in complete sentences at age two, supposedly analyzing Nietzsche by age ten, performing Shakespeare in his teens, staging the landmark “Voodoo Macbeth” at age twenty—and yet the role his voice played in his spectacular youthful ascent isn’t analyzed often. That preternaturally mature instrument helped enable the orphaned sixteen-year-old and rather baby-faced Welles to literally talk his way into roles with Dublin’s Gate Theatre. Listen to the talk of an average teenage boy, even one who’s an actor, and ask yourself if anyone in their right mind would cast him in a commercial stage production as the evil Duke of Württemberg in Jew Süss, Welles’s first role at the Gate.

Rounding out a good year, assignment-wise, the Siren sang the praises of the eternally beautiful 7th Heaven for the San Francisco Silent Film Festival's Day of Silents.

Rounding out a good year, assignment-wise, the Siren sang the praises of the eternally beautiful 7th Heaven for the San Francisco Silent Film Festival's Day of Silents. While Borzage was still preparing 7th Heaven, F.W. Murnau had arrived at Fox in 1926 to much fanfare and was filming his masterpiece, Sunrise, a production that continued even after Borzage’s film began shooting. (In an incredible feat of endurance, for a short period of time in January 1927, Janet Gaynor was shooting Sunrise exteriors for Murnau by day and returned to the Fox studio at night for 7th Heaven.) The German master’s presence exerted an influence on nearly everyone in the studio. Many critics have noted that certain 7th Heaven camera movements, such as the shot that follows Nana pursuing Diane into the street (achieved, Palmer recalled, by having eight men carry an eight-by-eight platform on which the cameraman rode with his tripod), bear Murnau’s influence. But Borzage’s emotional effects were entirely his own.

Published on December 19, 2018 06:38

October 23, 2018

Anecdote of the Week: "She hated him."

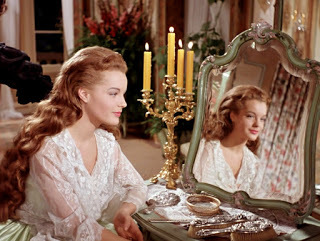

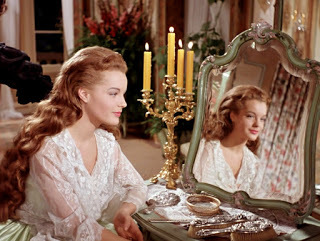

Over on Twitter, the Siren has been been working on a daily hashtag called #OctoberAlternative, a thread that lets her post stills from movies that put her in an autumnal (and therefore good) mood. The movies are not horror, however, since the horror genre tends to cover October like kudzu and sometimes a person needs a break. Today’s movie was Gone to Earth, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s adaptation of a Mary Webb novel.

Filmed in the fall of 1949 in Powell’s native Shropshire, the film was lensed by Christopher Challis in some of the most stunning Technicolor the Archers ever produced. As the Siren wrote a while back, Gone to Earth stars Jennifer Jones as Hazel Woodus, a half-wild girl who roams the countryside with her pet fox, and is loved chastely by a Baptist minister (Cyril Cusack), and carnally by a ruthless squire (David Farrar). She marries the reverend, and he refrains from consummating the union, believing Hazel’s innocence shouldn’t be profaned. But the squire has no such scruples, and he continues to pursue Hazel, even as it remains clear that she belongs not to men but to the earth of the title. (The Siren wrote about the movie in tandem with Tony Dayoub, and a different segment of our exchange can be found at his place.)

It is one of Powell and Pressburger’s best movies, and Jones was never better. But there was a unlucky force present at Gone to Earth’s birth, and its name was David O. Selznick, who had begun an affair with Jones in 1942 that wrecked both his marriage to Irene Mayer and Jones’s union with Robert Walker. He had long since begun the obsessive control of Jones’ image and career that would mark the rest of his life. Selznick and Jones eventually left their respective spouses, and they had been married to each other only a matter of weeks before the start of filming.

During production Powell and Pressburger were assailed with the usual Selznick memos—no one escaped those memos—but paid them no mind. Selznick in turn largely stayed away, just showing up from time to time to check on Jones and take her on weekend jaunts. But when Powell and Pressburger screened the film for him, Selznick popped a Benzedrine and said, “I’m not satisfied with your cut, boys. I’m going to take this picture over.” Despite this threat the original version was released in Europe, where it didn’t perform well. Unfortunately, Selznick had obtained the North American rights. Eventually he reshot a third of the footage with Rouben Mamoulian at the helm, slashed away another half-hour, and re-released it in 1952 with the ghastly title of The Wild Heart. That version, hopelessly marred by all accounts except possibly Selznick’s, flopped, too. There is a Region 2 UK DVD available of the original Gone to Earth, but it has never been available on Region 1 in the US.

And now for what prompted this post, which concerns some matters the Siren has wanted to write about for a while. Since the Siren and Tony wrote about this film seven years ago, there have been a few things published about Jennifer Jones, notably a long section of the late Jean Stein’s West of Eden. Jones doesn’t come off particularly well in it. Like Edie: An American Biography, West of Eden is a compilation of interviews, and most of the people interviewed seemed to look down on or outright dislike Jennifer Jones. Dennis Hopper, who lived with the Selznicks for a time along with his then-wife Brooke Hayward, remarked that Jones was eventually a disappointment to Selznick: “She couldn’t fulfill what he had in mind for her as an actress. She just wasn’t that good.” Jones’s obsession with clothes and appearance is detailed at length; she’s described showing up two and a half hours late to her own dinner party, making the rounds of the guests, disappearing, coming back in a second dress, then leaving and returning in a third dress.

Her son Robert Walker Jr. speaks of her with sympathy, but he has some sad memories. And indeed there is a lot to regret in the way Jones’s life played out, particularly in how she approached being a mother. “It was quite obvious that she wasn’t there for her children for a while,” says plain-spoken Lauren Bacall. The most tragic of the Selznicks was undoubtedly David and Jennifer’s daughter Mary Jennifer, who committed suicide in 1976. “By the time [Mary Jennifer] was seven,” says Brooke Hayward, “it seemed Jennifer had lost interest in her.” Jones herself attempted suicide more than once, although a couple of West of Eden interviewees imply that they didn’t believe she was serious about it. She was in therapy for years and apparently had affairs with at least a couple of her therapists.

There are a lot of folks on the classic-film blogs and classic-film Twitter who dislike Jennifer Jones, sometimes because her acting doesn’t click for them, often for having broken Robert Walker’s heart. (Walker, it should be said, was an alcoholic, and the marriage may have been doomed in any case.) West of Eden was a bestseller, and is full of the kind of anecdotes and observations that attach to a star’s image and don’t easily rub off: Nutty. Vain. Bad mother. Not that good.

The Siren has written of her regard for Jones as an actress, and she persists in seeing Jones the woman with some sympathy. It isn’t that the Siren believes West of Eden isn’t true, although the Siren wouldn't have asked Dennis Hopper, a Method actor from an entirely new generation, for an evaluation of Jones as an actress. It’s that there are always more angles to the truth about anyone.

Michael Powell had a different angle on Jennifer Jones. It is undoubtedly colored by his low opinion of Selznick, but like the people in West of Eden, he is telling his own version of events. In Million Dollar Movie, the second volume of Powell's autobiography, pokes gentle fun at Jones’s provincialism, such as her complaining to Chris Challis about Europeans’ refusal to speak English, or describing the volcanic island of Stromboli as “kinda cute.” But Powell admired her acting — “Jennifer was splendid” — as well as her dedication to her part. He tells of how she spent every spare minute with the film’s tame fox, developing a bond with Foxy that even surprised the trainer. She was always cuddling the many other animals on set and rebuking the crew for laughing at them, because animals hate being laughed at. “She went through the film,” said Powell, “as if she were the real Hazel playing herself.”

As for Jones the person, what Powell offers is one of the saddest pictures of a toxic relationship you will ever read. When Selznick visited, his conversations with Jones went like this: “ ‘... We could go to Istanbul first, honey.’ ‘I don’t know, David. You decide,’ Honey responded, without opening her eyes.” Otherwise, Selznick stayed away, and relied on word from “his spies,” as Powell put it.

Late in filming Powell found himself having to shoot some interiors at night. The “set” for these scenes were makeshift studios set up in local buildings. One night the scenes went slowly, and Jones was left in the bar of the pub set drinking the local cider, which Powell said “could set your head spinning” after a couple of pints. Finally it came time for Jones’s entrance, only she refused to come when summoned by the assistant. Powell went to see what was the matter. And the matter was that Jones was drunk.

‘How much has she had?’ I said to the scared barman. He was a local extra.

‘Quite a bit.’

I held on to her mug, but she grabbed another and was doing the Anna Christie bit, slumped across the table. ‘Well, what are you and Mr. Fucking Selznick going to do about it?’

It was not the Jennifer we knew, the eager and nervous girl. It was a tragic woman speaking. She went on, ‘Don’t try to play the director with me, Micky. You don’t know what it’s all about, but I do. How would you like to be murdered? Murdered every night and lie there waiting for it? What do I care about you and your picture? Screw you! And screw your picture and screw … Mr. … Mr. Selznick, the greatest producer in the world … the … ’

From there her language got a lot worse, and Powell realized his filming was done for the night. He called for a car, rugs, and a bucket. Jones was guided into the car, Powell sat next to her, and as the driver went round and round in large circles, Jones was sick, and then she began to talk, and talk.

Out it all came.

She hated him. He had forced himself into her life uninvited, been repulsed again and again, had broken her marriage, destroyed her husband, alienated her children, and was such an appalling egoist that he believed his attentions could compensate for all the harm he had done. He had enslaved her with a contract that promised to make her the greatest star in the world, without the least knowledge of how to do it, and expecting other people to do it for him. He was dragging her about Europe as if she were the captive of his bow and spear, and everyone assumed that she was madly in love with him. She hated him. But worst of all, he had decided that they must be married, not because he wanted to give her children a stepfather, not because he wanted a child himself from her, but because he wanted to show the whole of show business that he was not like other men. He had brought her to Europe to take her away from her family and friends. He took her with him everywhere … She dreaded each moment that they were left alone. They only peace that she had had been on Gone to Earth. We were all so kind and she loved everybody and she loved Foxy and it wasn’t like being on a film at all. But in three weeks the film would be over and then what would she do? … She wished she could escape — run away — but there was no escape, none, none, none! None of us could understand what her life was like. Nobody could understand what it was like living with a man like David.

Eventually Jones fell asleep on Powell’s shoulder, and they took her back to her hotel.

Million Dollar Movie contains a coda where Powell has dinner with Jennifer Jones, now Mrs. Norton Simon, at her Malibu mansion in 1978. (Selznick had died of a heart attack in 1965.) Powell says Jones was heavily made up, but she didn’t change her dress or disappear during the meal. He also says “she talked about David O. without rancour.”

“We were all crazy about Jennifer,” said Lauren Bacall, “but we saw the flaws.”

Published on October 23, 2018 12:27

February 7, 2018

Anecdote of the Week: 'Spit It Out'

A story told by John Sayles, from a wonderful 1995 conversation between him and historian Eric Foner. Their dialogue opens the book Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies.

You know, one of the things I often do—for instance, when I wrote Eight Men Out—is read a lot of the period writers, especially guys who were known to have had an ear for dialogue—Ring Lardner, James T. Farrell, Nelson Algren. I also showed the actors Jimmy Cagney films because there was a speed of delivery affected by urban guys then that Jimmy Cagney used. Actors today, since they've been through the 'method revolution,' take these incredibly long pauses. I showed them a movie called City for Conquest in which a hundred different things happen in an eighty-minute movie because everybody talks really fast. I told the actors—except the one who played Joe Jackson, because he was supposed to be from Georgia—'This is your rhythm. Spit it out.' That made a statement back then, spitting it out.

The Siren's own explanation for the swift glorious brevity of so many old movies had always been elegance of exposition. She's been rewatching the Budd Boetticher/Randolph Scott Westerns, for example, and in just about all of them, you get a character's whole lifetime expressed in one or two lines of dialogue. And they certainly don't talk fast! But Sayles is right: Other movies keep the plot barreling along via sheer speed of dialogue. Both Howard Hawks and Billy Wilder were masters at that.

The Siren notes, however, that Sayles' memory was playing a small trick on him, since the runtime for City for Conquest is usually listed as 104 minutes. Of course, the quote is from 1995, when most people didn't have the Internet to help them be a smart-alec.

P.S. The Siren has written an article surveying the Museum of Modern Art series "Martin Scorsese Presents Republic Rediscovered: New Restorations from Paramount Pictures." You can find it here at the Village Voice. The series runs through Feb. 15 at MoMA.

Published on February 07, 2018 06:56

December 30, 2017

2017: The Year in Old Movies (because measuring it in other ways wouldn't be nearly as pleasant)

The 10 best of what the Siren watched in 2017, presented without preamble, and in alphabetical order. The Siren wishes her patient readers a most happy 2018.

The Big City (Mahanagar; directed by Satyajit Ray, 1963. Viewed on Criterion DVD)

Madhabi Mukherjee’s performance instantly became an all-time favorite. It is part of Satyajit Ray’s genius that he refuses to make her husband (Anil Chatterjee, half lummox, half mensch) into a villain, instead showing how the man’s prejudices give way not only to love of his wife, but common sense.

Bitter Stems (Los Tallos Amargos; directed by Fernando Ayala, 1956. Viewed at Metrograph)

The Siren thinks this may be the noirest noir of them all. The movie weaves together guilt and ambivalence over Argentina’s history in World War II with the hero’s (Carlos Cores) own psychological unraveling. Magnificent cinematography by the Chilean Ricardo Younis. Do read Raquel Stecher’s post on the film’s restoration; you will see how close we came to losing this beauty forever. The Siren was so impressed that she donated to the Film Noir Foundation as thanks.

The Glass Tower (Der gläserne Turm, directed by Harald Braun, 1957. Viewed during Film Society of Lincoln Center’s series The Lost Years of German Cinema: 1949–1963.)

A classic women's picture about the emotional abuse inflicted on a former actress (Lilli Palmer) by a secretly psychotic tycoon husband (O.E. Hasse). You’d know this film influenced Rainer Werner Fassbinder even if the program notes never said so. The Siren loved the way it suddenly became almost an Agatha Christie mystery, loved the design (by Walter Haag) that envisions the couple’s life as a series of elegant glass-walled prison cells. The plot resembles Under Capricorn, but the film plays out to its resolution in a much more satisfying way. (Bosley Crowther’s review is possibly the most sexist thing he ever wrote, which is saying something.)

I’ll Be Seeing You (directed by William Dieterle, 1945. Viewed on Kino Classics DVD).

Somehow the Siren had missed this delicate wartime romance, which boasts one of Ginger Rogers’ most heartfelt and touching performances. As her character and that of Joseph Cotten gradually fall in love, you realize you are watching two psychically wounded people trying to heal. The Siren much prefers this to the better-known Love Letters (same year, same director), which has a torpid screenplay by Ayn Rand; I’ll Be Seeing You has a screenplay by Marion Parsonnet, whose credits include Gilda. The Siren saw I’ll Be Seeing You while researching her video essay on Ginger Rogers’ dramatic roles, which will be included in Arrow Films’ Blu-Ray release of Magnificent Doll in February 2018.

Le Trou (The Hole; directed by Jacques Becker, 1960. Viewed at Film Forum’s run of the 4K digital restoration.)

The Siren has a new favorite prison movie. And while this may surprise you, the Siren tends to like prison movies. The late-movie payoff is one that many Hollywood directors would sell a kidney to come up with.

Paris Frills (Falbalas; directed by Jacques Becker, 1945. Viewed on MUBI.)

It’s a pity this isn’t widely available, as it makes a terrific companion piece to Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread. The Siren would love to know if Anderson saw it. Paris Frills also concerns an egotistical couturier (Raymond Rouleau), whose atelier is also in a palatial townhouse, and who also runs roughshod over the people around him, with much different consequences. Becker is more concerned than PTA with the daily labor of “les petits mains” and with suggesting all the lives beyond those of his leads. The Siren’s favorite scene involved the couturier, deep in a selfish funk about a love affair, being told off by Solange (Gabrielle Dorziat), his equivalent of Phantom Thread’s Cyril: “I don’t give a damn about her. She has time for sentimental complications, where here there are 300 who can’t be permitted that, and who you are going to put out in the street.” (Note for the Siren’s fellow lovers of fashion history: The gowns were by Rochas.)

Roses Bloom on the Moorland (Rosen blühen auf dem Heidegrab; directed by Hans H. König, 1952. Viewed as part of the FSLC Lost Years series.)

The Siren’s surprise of the year. One alternate title is Rape on the Moorland, which didn’t exactly sound like her sort of thing, and she saw it only because it was screening at a rare moment that found her in the Walter Reade neighborhood. The film turned out to be a unique combination of Universal horror movie and rural romance, with Ruth Niehaus splendid as the death-haunted peasant heroine, and Hermann Schomberg storming through his scenes as the bestial villain. König makes exquisite use of the windswept, Bronte-esque setting, but what really sold the Siren was the denouement, with its unexpected warmth and humanity.

Ruthless (directed by Edgar G. Ulmer, 1948. Viewed as part of the MoMA series “Poverty Row.”)

Written about in the Siren’s roundup of this series at the Village Voice.

The Spy in Black (directed by Michael Powell, screenplay by Emeric Pressburger, 1939. Viewed on MUBI)

Yes yes, everybody else already got to this one; better late than never, my friends. Terrific-looking BFI restoration. Conrad Veidt has a great doomed romantic part even though he's nominally the villain. Excellent location work in the Orkneys. A coolly intriguing performance by Valerie Hobson, who ordinarily doesn’t excite the Siren.

Tonka of the Gallows (Tonka Sibenice, directed by Karel Anton, 1930. Viewed as part of MoMA’s series “Ecstasy and Irony: Czech Cinema, 1927–1943.”)

The Siren wrote her heart out about this one at her Film Comment blog.

Honorable mention, among many others seen and enjoyed:

I Knew Her Well (Antonio Pietrangeli, Italy 1965)

Kristian (Martin Fric, Czechoslovakia, 1939)

Happy Journey (Otakar Vavra, Czechoslovakia 1943)

False Faces (Lowell Sherman, U.S. 1932)

Sword of Doom (Kihachi Okamoto, Japan 1966)

Black Gravel (Helmut Kautner, Germany, 1961. Note: This one is not for dog lovers.)

###

What follows is a roundup of some of the work that the Siren did elsewhere this year, aside from those already mentioned above.

Booklet essay for the Masters of Cinema Blu-Ray of Cover Girl (a stunning restoration, by the way).

Booklet essay for Criterion’s Blu-Ray of His Girl Friday .

Booklet essay for Criterion’s Blu-Ray of The Philadelphia Story.

Booklet essay for Film Movement’s Blu-Ray box set of the Sissi movies, starring Romy Schneider.

For the Village Voice, a write-up of "Hank and Jim," a series at Film Forum linked to Scott Eyman’s wonderful book about the deep, lifelong friendship between Henry Fonda and James Stewart.

Also for the Voice, an essay about the William Wyler series that ran at the sparkling new Quad Cinema.

"What Makes Lubitsch Lubitsch?" at the Voice, a chance to ramble on about the master, via the Film Forum's near-complete retrospective.

For the San Francisco Silent Film Festival's program, I wrote an essay on The Doll, a 1919 silent from Lubitsch's Berlin period, starring the irrepressible Ossi Oswalda.

An essay on the magnificent Marseille Trilogy, again at the Voice.

For her blog at Film Comment, in addition to her essay on Tonka, the Siren wrote on

Michèle Morgan

Beat the Devil

The Stranger

The Last Man on Earth & It’s Great to Be Alive

The “Roman Hollywood” series at Film Forum; this blog post includes the Siren holding forth briefly on her love for Three Coins in the Fountain.

The Big City (Mahanagar; directed by Satyajit Ray, 1963. Viewed on Criterion DVD)

Madhabi Mukherjee’s performance instantly became an all-time favorite. It is part of Satyajit Ray’s genius that he refuses to make her husband (Anil Chatterjee, half lummox, half mensch) into a villain, instead showing how the man’s prejudices give way not only to love of his wife, but common sense.

Bitter Stems (Los Tallos Amargos; directed by Fernando Ayala, 1956. Viewed at Metrograph)

The Siren thinks this may be the noirest noir of them all. The movie weaves together guilt and ambivalence over Argentina’s history in World War II with the hero’s (Carlos Cores) own psychological unraveling. Magnificent cinematography by the Chilean Ricardo Younis. Do read Raquel Stecher’s post on the film’s restoration; you will see how close we came to losing this beauty forever. The Siren was so impressed that she donated to the Film Noir Foundation as thanks.

The Glass Tower (Der gläserne Turm, directed by Harald Braun, 1957. Viewed during Film Society of Lincoln Center’s series The Lost Years of German Cinema: 1949–1963.)

A classic women's picture about the emotional abuse inflicted on a former actress (Lilli Palmer) by a secretly psychotic tycoon husband (O.E. Hasse). You’d know this film influenced Rainer Werner Fassbinder even if the program notes never said so. The Siren loved the way it suddenly became almost an Agatha Christie mystery, loved the design (by Walter Haag) that envisions the couple’s life as a series of elegant glass-walled prison cells. The plot resembles Under Capricorn, but the film plays out to its resolution in a much more satisfying way. (Bosley Crowther’s review is possibly the most sexist thing he ever wrote, which is saying something.)

I’ll Be Seeing You (directed by William Dieterle, 1945. Viewed on Kino Classics DVD).

Somehow the Siren had missed this delicate wartime romance, which boasts one of Ginger Rogers’ most heartfelt and touching performances. As her character and that of Joseph Cotten gradually fall in love, you realize you are watching two psychically wounded people trying to heal. The Siren much prefers this to the better-known Love Letters (same year, same director), which has a torpid screenplay by Ayn Rand; I’ll Be Seeing You has a screenplay by Marion Parsonnet, whose credits include Gilda. The Siren saw I’ll Be Seeing You while researching her video essay on Ginger Rogers’ dramatic roles, which will be included in Arrow Films’ Blu-Ray release of Magnificent Doll in February 2018.

Le Trou (The Hole; directed by Jacques Becker, 1960. Viewed at Film Forum’s run of the 4K digital restoration.)

The Siren has a new favorite prison movie. And while this may surprise you, the Siren tends to like prison movies. The late-movie payoff is one that many Hollywood directors would sell a kidney to come up with.

Paris Frills (Falbalas; directed by Jacques Becker, 1945. Viewed on MUBI.)

It’s a pity this isn’t widely available, as it makes a terrific companion piece to Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread. The Siren would love to know if Anderson saw it. Paris Frills also concerns an egotistical couturier (Raymond Rouleau), whose atelier is also in a palatial townhouse, and who also runs roughshod over the people around him, with much different consequences. Becker is more concerned than PTA with the daily labor of “les petits mains” and with suggesting all the lives beyond those of his leads. The Siren’s favorite scene involved the couturier, deep in a selfish funk about a love affair, being told off by Solange (Gabrielle Dorziat), his equivalent of Phantom Thread’s Cyril: “I don’t give a damn about her. She has time for sentimental complications, where here there are 300 who can’t be permitted that, and who you are going to put out in the street.” (Note for the Siren’s fellow lovers of fashion history: The gowns were by Rochas.)

Roses Bloom on the Moorland (Rosen blühen auf dem Heidegrab; directed by Hans H. König, 1952. Viewed as part of the FSLC Lost Years series.)

The Siren’s surprise of the year. One alternate title is Rape on the Moorland, which didn’t exactly sound like her sort of thing, and she saw it only because it was screening at a rare moment that found her in the Walter Reade neighborhood. The film turned out to be a unique combination of Universal horror movie and rural romance, with Ruth Niehaus splendid as the death-haunted peasant heroine, and Hermann Schomberg storming through his scenes as the bestial villain. König makes exquisite use of the windswept, Bronte-esque setting, but what really sold the Siren was the denouement, with its unexpected warmth and humanity.

Ruthless (directed by Edgar G. Ulmer, 1948. Viewed as part of the MoMA series “Poverty Row.”)

Written about in the Siren’s roundup of this series at the Village Voice.

The Spy in Black (directed by Michael Powell, screenplay by Emeric Pressburger, 1939. Viewed on MUBI)

Yes yes, everybody else already got to this one; better late than never, my friends. Terrific-looking BFI restoration. Conrad Veidt has a great doomed romantic part even though he's nominally the villain. Excellent location work in the Orkneys. A coolly intriguing performance by Valerie Hobson, who ordinarily doesn’t excite the Siren.

Tonka of the Gallows (Tonka Sibenice, directed by Karel Anton, 1930. Viewed as part of MoMA’s series “Ecstasy and Irony: Czech Cinema, 1927–1943.”)

The Siren wrote her heart out about this one at her Film Comment blog.

Honorable mention, among many others seen and enjoyed:

I Knew Her Well (Antonio Pietrangeli, Italy 1965)

Kristian (Martin Fric, Czechoslovakia, 1939)

Happy Journey (Otakar Vavra, Czechoslovakia 1943)

False Faces (Lowell Sherman, U.S. 1932)

Sword of Doom (Kihachi Okamoto, Japan 1966)

Black Gravel (Helmut Kautner, Germany, 1961. Note: This one is not for dog lovers.)

###

What follows is a roundup of some of the work that the Siren did elsewhere this year, aside from those already mentioned above.

Booklet essay for the Masters of Cinema Blu-Ray of Cover Girl (a stunning restoration, by the way).

Booklet essay for Criterion’s Blu-Ray of His Girl Friday .

Booklet essay for Criterion’s Blu-Ray of The Philadelphia Story.

Booklet essay for Film Movement’s Blu-Ray box set of the Sissi movies, starring Romy Schneider.

For the Village Voice, a write-up of "Hank and Jim," a series at Film Forum linked to Scott Eyman’s wonderful book about the deep, lifelong friendship between Henry Fonda and James Stewart.

Also for the Voice, an essay about the William Wyler series that ran at the sparkling new Quad Cinema.

"What Makes Lubitsch Lubitsch?" at the Voice, a chance to ramble on about the master, via the Film Forum's near-complete retrospective.

For the San Francisco Silent Film Festival's program, I wrote an essay on The Doll, a 1919 silent from Lubitsch's Berlin period, starring the irrepressible Ossi Oswalda.

An essay on the magnificent Marseille Trilogy, again at the Voice.

For her blog at Film Comment, in addition to her essay on Tonka, the Siren wrote on

Michèle Morgan

Beat the Devil

The Stranger

The Last Man on Earth & It’s Great to Be Alive

The “Roman Hollywood” series at Film Forum; this blog post includes the Siren holding forth briefly on her love for Three Coins in the Fountain.

Published on December 30, 2017 12:09

December 26, 2017

Seeing Out 2017 With the Great Lee Grant

The last few months of 2017 have found me craving escape, and I’ve been rewatching Columbo episodes to help me unwind before bed. A couple of weeks ago, I curled up with Ransom for a Dead Man from 1971, which stars Lee Grant as a highly accomplished attorney with a boring old husband and a boring young stepdaughter. Grant’s character shoots the husband and spends the rest of the 90 minutes securing her inheritance, while coolly treating the suspicious stepdaughter like she’s the one who’s nuts. The woman is so steely that her idea of relaxing is flying a plane over a nice big set of mountains. I love it, as I always love Lee Grant.

As an actress, Grant uses everything: her voice, her use of even the smallest gestures, her listening and concentration, her extraordinary feline beauty, and most of all her humor. She brings a sense of life’s madness even to her most dramatic roles. Of course, like many another talent, Lee Grant had to find her own way to cope with Hollywood’s dearth of good parts for older women. Unwilling to compromise on the kinds of projects she wanted, she shifted to directing, amassing another impressive filmography.

Artist, blacklist survivor, liberal activist, and trailblazing feminist: Lee Grant has always been an idol to me. So the chance to interview her for the Los Angeles Times, ahead of the TCM Film Festival’s three-film tribute (Detective Story, In the Heat of the Night, The Landlord) this past April, was easily a highlight of my life, let alone 2017.

When I walked into her roller-rink-sized apartment in Manhattan, accepted a cup of tea and settled in, Grant mentioned her New York childhood and the apartment where she grew up, lovingly described in her 2015 memoir, I Said Yes to Everything.

“Which you haven’t read,” she added.

“Oh, but I did read it. All of it,” I bragged, ready to be teacher’s pet.

“Great,” was the deadpan response. “We don’t have to do the interview.”

Needless to say, my admiration for Grant turned into outright love at that moment.

The result of our conversation ran in the LA Times and can be read here. But she had so much to say that was worthwhile, especially to a film fan, that I wanted to include other parts that were left out for reasons of space.

# # #

Farran Nehme: I want to start with Detective Story [play 1949, film 1951]. You were such a distinctive actress right out of the box. You used a voice that was not your own. You had a lot of very specific actions for this very nervous person who can’t believe she’s been arrested.

Lee Grant: The voice I picked up when I was at the Neighborhood Playhouse, in language and speech class. When I went into the Neighborhood Playhouse, I had a little-bitty voice way up here because my mother and my aunt thought that rich ladies [shifts to high] spoke all the way up here, like they saw in the movies. [back to normal voice] And so I went into school, and they took a recording, and I heard myself for the first time. I heard [up high] this voice coming up way up here. [back to normal] And so they taught me to speak from the chest. And one of the assignments I had was to listen to other people’s voices. So I was on a bus, and I heard these girls talking, in the seat in back of me. Like, “Vere else? Vere else should I go?” The r was v. “Vat do you think ve should do?”

And so I was transfixed by the new language, and I brought it into class. And then after I graduated, when I got this call to go up for [the Broadway production of] Detective Story, they offered me the female, the ingenue lead [played by Cathy O'Donnell in the movie]. And as I wrote, I couldn’t say the words. He [the detective] asks, “What color are his eyes?” and... [the ingenue] says “brown and green, flecked with gold.” And I said, "Can I play the old lady?" Because at that time the shoplifter was described as 40. And I was 23 or 24 at the time. So I got the old lady part. And that’s the kind of part I always wanted.

FN: Even though it was smaller.

LG: Well, you know, those big parts are not the most interesting parts. And those big parts...you know, every other woman’s part in that was fucking boring. It kind of set my agenda for life. Because the big parts were not only thankless, but they depended on you to fill the theater and bring in the box office. So you not only had a boring part, but everything depends on you. And that was so not fun for me as an actor. And so I pretty much, except for playing leads in television, I pretty much always stuck to the most interesting part I could play.

FN: So then, of course, after winning at Cannes and being nominated for the Oscar, you were sucked into the maelstrom of the blacklist.

LG: The year that I was nominated for the Oscar, 1952, was the year that I couldn’t work in TV or film anymore. For 12 years. From age 24 to 36.

FN: Key years for an actress.

LG: Well! Hel-LO! Especially in Hollywood. Your career is over at 36. I was terrified when I [went back to] Hollywood that my age would be known, because I was being cast in parts that were 10 years younger. And that the FBI would find out that I was working. You know, that whole 12 years of hiding and fear.

FN: You came back fully as forceful a movie actress as you’d been before.

LG: First in Electra. [That would be the 1964 New York Shakespeare Festival production of Sophocles' Electra, directed by Joseph Papp and performed at the opening of the Delacorte Theatre in Central Park.] I say it because the whole focus was on me. I wasn’t doing a character part… And so the rage that I had that was stored up in me for 12 years was given the kind of— I mean, this is Greek tragedy, and it was me in rags and barefoot on the stage in Central Park, where all of the things that were suppressed were let loose. It was the Greek catharsis… I was working for him [Papp] regularly, and I was with him the next summer when I got the call to do [the TV series] Peyton Place… I could have stayed and done that kind of work forever. Or gone to LA and changed my life and gone on to money.

FN: Was that part of it? Money?

LG: Oh, totally. I had none, and I had a little girl to support. It was just me and Dinah [Manoff, Grant’s elder daughter].

FN: So you accepted the part in Peyton Place, as the blacklist was ending. But you did do a few movies before that. You did a movie called Middle of the Night [1959].

LG: Yes. That was during the blacklist.

FN: And you did another film in the middle of the blacklist that I'm intrigued with, directed by Cornell Wilde, called Storm Fear [1955]. [Grant laughs heartily] I haven’t seen it but I want to track it down. It looks like an interesting part for you.

LG: Oh, it’s terrible. That was the movie in which Dinah was conceived. Because it would give us money enough to have a child. [At the time, Grant was married to writer Arnold Manoff, who was also blacklisted.] So all those jobs were connected to what was possible.

FN: So at least Storm Fear brought you Dinah.

LG: Bungalow 3 at the Chateau Marmont.

FN: I couldn’t find that movie in your memoirs and I thought, she doesn’t like it.

LG: It was a disaster.

FN: Middle of the Night [1959] though, is a lovely movie.

LG: Fredric March, was oh, he was so beautiful in that, and so was Kim Novak. It was the only picture in which I felt she was absolutely present, that there was that shyness in her, that I’m not really this big tall glamour girl, I’m really a shy typist, yearning for a father. I just thought, such a lovely film. And the director [Delbert Mann], whose name escapes me, as a lot of names do, this was during the blacklist. He gave me a part in a movie. Small part, but it was a part in a movie, during the blacklist. And so I’m just so grateful for those guys who put themselves in jeopardy to hire me.

FN: In the Heat of the Night [1967] was such an important film for you personally and also in general. A landmark. And another example of a small but telling role. Your character is the first one who gives us the sense of the murder victim as a human being, with your shock and grief when Sidney Poitier tells you the news. And you say, “Is it hot in here”?

LG: I think a lot of that was improvised. I don’t know if that was a line in the script. But Norman [Jewison] gives so much freedom to his actors. I met with him and [the film's editor] Hal Ashby once, and I knew that part. I had a sense that they knew about me, that they knew about the blacklist, they were very political people. We never discussed it. And when they spoke to me I just went into that place, of the loss. Just talking back and forth, I went into that woman. And I don’t think we shot more than two or three days. I got there and Sidney and Rod embraced me: “Come and have dinner.” I went to bed, I got up, I was the woman.

And then we improvised that scene. And I remember Haskell Wexler following me with the camera. And Sidney and I had this dance. This kind of Strindberg dance. And then it was over. But that sense of that bubble, of allowing an actor to go into that place that unfortunately I knew only too well, and to see where it took us both, was something that very few directors would do. You know, “It’s the line, it’s the line, it’s the line.” This was not. I didn’t know what would happen. And Sidney didn’t know what would happen. And so it’s that exploration.

[snip]

FN: You’re also in one of the most famous scenes, when you’re standing there during the investigation, and Rod Steiger asks, “Well what do you they call you up there in Philadelphia, boy?” and Poitier responds, “They call me Mr. Tibbs.” And after, you are the one who interrupts and says “What kind of people are you? I’ve lost my husband!” But when the camera is not on you, I still can feel you watching and listening. Were you there, when those lines were filmed?

LG: Of course. Method actor. And so was Sidney, and so was Rod. We’re serious, and we’re there to support each other.

FN: I don’t think it would play the same way if we couldn’t feel you there.

LG: No. Nor would he be able to play it the way he did, if he didn’t have my support, my character there.

FN: So that was a triumph.

LG: It was more than a triumph. That film was life-changing. Nobody saw a Mr. Tibbs before, like Sidney. Sidney broke ground for black actors, for romantic leads, forever. Sidney did that. I did a documentary on Sidney when I was doing docs for HBO and American Masters. And I saw where that strength in himself and that vitality and the humor came from. Cat Island [Poitier’s childhood home in the Bahamas]. He came from a place of freedom, where the people in charge were black. It wasn’t white on black, it was black. And he brought that to the United States and he brought that to film. He brought that sense of dignity and rage at inequity. It was a natural thing for Sidney.

[The next exchange concerns Portnoy’s Complaint (1972), directed by Ernest Lehman. Grant had a bad time with Lehmann, whose talent she admired, but whom she called in her memoirs “an angry, small man with his neck pushed forward,” a description so good I apply it to a different person nearly every time I turn on the news. During the last week of filming, Grant’s character, Sophie Portnoy, had a hospital scene where the woman in the other bed was played by an Actors’ Studio alumna who had one line. Lehman hated the actress’ line delivery no matter how she delivered it, screaming at the woman for an hour while Grant tried to wait it out so she could play a key scene with Richard Benjamin as her son. Finally, as the shattered actress began weeping, Grant could take it no longer, and yelled at her director: “Stop it, stop it! You’re torturing her to death, you little shit.” Grant raged on at Lehman, “Get out of here!... Go to the camera trailer and direct from there. Dick and I will do the scene without her line.” Lehman went. They finished the scene. Grant noted that a line can always be fixed in postproduction, and Lehman was “playing Erich von Stroheim.” When she saw Portnoy’s Complaint in the theater, one time only, Grant said it “made me shrink back in horror. It was not a good representation of Jewish family life.”]

FN: You had that rage too. The story on Portnoy’s Complaint, when you were working with Ernest Lehmann. I felt that story revealed something really fundamental about your personality, when the actress was being bullied. Would you agree that’s part of your character?

LG: Absolutely. I cannot bear endangering and bullying. I can’t bear it.

FN: There can’t be many actresses that have thrown a director off his own set.

LG: [pause, then a chuckle] No, as a matter of fact, I don’t think that there have been.

FN: So you met Hal Ashby when you doing In the Heat of the Night, and the other movie at the TCM film festival is The Landlord [1970]. How was that as a filmmaking experience?

LG: Well, they had Jessica Tandy for the part. Older than me. And I knew that part so well. It was so much a part of the personalities of my mother and my aunt. The wonderful, ridiculous part of them. Not that they weren’t great and loving people, but there was a ridiculous part that they and this woman had. So I fought very hard [for the part]. And I saw it recently, and I loved it. I loved myself, I loved Pearl [Bailey, who’s superb]. And of course Hal had been the one who picked out my hairstyle and the clothes for In the Heat of the Night. And so we became friends, and this was his first movie. So that was a continuation of the relationship. Norman produced it, and Hal was directing it. And Hal had this unique take on everything, all of his movies had a unique, totally undone, fresh way of looking on things.

FN: And how did that extend to working with the actors? Because you worked with him not only on this, but five years later on Shampoo, which won you an Oscar.

LG: Hal’s credo was, “Surprise me.” and that was for all his actors. And what could be more talent-provoking than to say to someone, “Surprise me?” It was just delicious.

FN: There’s a lot of surprising moments in that scene with Pearl Bailey. At one point you’re stretched out on the floor….

LG: Yes!

FN: The wonderful way you say, when she asks if you’ve had lunch, [whispers] “I don’t have lunch.”

LG: I love it myself. And I think, “where did that come from?”

FN: Did either your mother or your aunt skip lunch?

LG: It wasn’t the skipping lunch. It was the [trills] “daaaarling.” It was that whole rich-lady-when-they-weren’t-rich. You know, rich lady, a persona, that they took on, that I was dying to explore.

FN: You talked about being afraid of having your age disclosed at certain points in your career. And yet some of your best parts—The Landlord, Detective Story— you’re playing someone older, and in fact you sought that out. Is there any kind of contradiction there?

LG: It’s the part. It’s the part. And the making myself younger and asking [the] Mayor to change my driver’s license to five years younger [Note: I Said Yes to Everything details how she did exactly that] that had nothing to do with the part, that had to do with the hiring. And when actors say, “How old are you?” “Oh, I’m 46.” [clucks in disapproval] “Ohhhh. I thought you were like in your 30s.” That’s hireability. That’s an actor protecting their hireability. That’s exactly what it’s based on. It’s not ego. It’s not. It’s that there is a date—what’s it called on the milk?

FN: The sell-by date.

LG: The sell-by date! There’s a sell-by date in Hollywood. And all of us women are acutely conscious of that sell-by date. I worked with the most beautiful actresses that were in Hollywood, who knocked it out of the park at the box office. Then one, two years later, the dailies come up and the heads of the studio are saying, “Eh, she looks old, she looks fat.” … And so juggling your liveability, your milk date, is a very important thing for an actor who’s supporting a child in Hollywood. And also one who was deprived of work for just as many years as I worked in Hollywood. There were 12 years I was out of work, then there were 12 golden years. And I walked away from it because I knew that my date had come up after the Oscar. I knew that I would not get the kind of parts in the [same] kind of movies. They were not being made anymore.

FN: Like Shampoo.

LG: Like Shampoo.

FN: Where you played a beautiful woman who’s getting it on with Warren Beatty. And you still felt that was it?

LG: It was an extraordinary film. That was of its time. The 70s was the time for directors. And Coppola, Spielberg, all those were new directors then. And they were making the kind of film that isn’t usual anymore. They were breaking entirely new ground. And… it was coming to an end.

[snip]

FN: When we move to your documentary work in the 1980s, I was staggered by the breadth of subject and how ahead of your time you always were. What Sex Am I, about transgender issues. Battered. Down and Out in America … As a documentary filmmaker, clearly you’ve been drawn to political topics.

LG: The blacklist was my education. I didn’t know anything. I was not interested in school. Really my education came from Tolstoy and Chekhov and reading. So those 12 years were my education. I learned, close to home, at home, what politics was all about. And what life was all about.

FN: And what was politics all about, when you looked back?

LG: Well, it was not that far from what we have now. It was McCarthy. And it was anybody. … I mean, I spoke at a man’s memorial. An actor’s memorial [Grant is referring to Joe Bromberg; she gave a eulogy at his memorial service in 1951. Bromberg, a longtime character actor from stage and film, had been named as a Communist by the notorious Red Channels magazine and called to testify in June 1951 before the House Un-American Activities Committee, where he took the Fifth. He died of a heart attack in London less than six months later, age 47.] I was 24. And I said [Bromberg] was afraid of going in front of the Un-American Activities Committee because he had a heart problem. And two days later, I was on a list which didn’t allow me to work in films or television anymore. You didn’t have to do much. [I was] faced with an ethical problem after that. Do I want to work in film or television, and go to the guy who does Red Channels, and say ‘I’m sorry, I didn’t mean it, the Un-American Activities Committee is really fun?’ The choice was clear.

FN: For you it was.

LG: It was. And also, I was in love with those people. The blacklisted people in California were a new breed. I never knew anybody like that. Ring Lardner, Zero Mostel, Sol Kaplan. And we were all living in 444 Central Park West. They were like professors to me. They were the education I never had. And I got very deeply involved with that outraged part of me, that you see. And the unfairness. As a kid, I could see what was fair and what wasn’t fair. That’s like in my DNA. And this unfairness was so palpable. For actors not being allowed to act, because they showed up at a meeting or they signed their name to something? And they’re not allowed to act? It was just enraging to me. That was my motor. And it was a very good one. It was a very good one.

And it was the motor for all those years when I kept quiet in Hollywood. Because I was so scared they’d stop me from working, that when I got out [of the acting business], I could finally say the things that I kept my mouth shut about when I was working.

FN: When you were working as an actress, you did not go out of your way to be political.

LG: No. I was scared of it… When you live long enough, from 24 to 36, under one condition, and then suddenly the music starts and you’re on this sunny island with the sand and the colony and the friends, it’s like, "Wait a minute! Where am I? Is this true, or isn’t it?"

FN: You once said that in your documentaries, “I can cover what the media distorts or doesn’t cover at all.”

LG: It’s my voice. It’s a voice I wasn’t allowed to use it for a long time. Documentaries are a way of exposing the thing that needs to be talked about. I was lucky enough to get three of them on television….

I’ll tell you what I’m working on now. I’ve made a five-minute video on "The Battering of Hillary Clinton." The battering and destruction of Hillary Clinton. This is a new place for me. I don’t know how to do any of those smartphones. I worked with a young student so he could put together things that I want to have seen. And I am going to do everything I can to get it out in and go, what’s the word?

FN: Viral?

LG: To go viral.

FN: So the treatment of Hillary Clinton hit you hard.

LG: Very, very hard. That’s a battered woman. How dare they.

(You can see "Battered: The Assault on Hillary Clinton" here, on Youtube.)

Published on December 26, 2017 12:02

August 1, 2017

Bad-Movie Double Feature

A long time ago the Siren was asked in the comments to a post on this here blog whether or not she had seen The Legend of Lylah Clare. And she said no, and some of you (the Siren names no names, you know who you are) said “Oh Siren! You should see it!”

So some time later (seven years, but who’s counting) the Siren did sit down and watch Lylah, and now she is back to ask, WHY DID YOU DO THIS TO HER?

The Legend of Lylah Clare is terrible. The Siren issues that judgment after watching it on an impromptu double bill with Where Love Has Gone which is, god knows, also bad, but bad in a fun, watchable, even sociologically interesting way. Where Love Has Gone answers the intriguing question of how the Johnny Stompanato murder would have played out if, rather than a movie star, Lana Turner had been a wealthy abstract sculptor in San Francisco, and its good points include, but are not limited to,

1. Late-period Susan Hayward, yelling at husband Mike Connors “You’re a drunk! A drunk, a drunk, a drunk!” in a slurred voice she probably perfected on the set of I’ll Cry Tomorrow

2. George Macready (second from left) classing up the joint as the family lawyer, as he nears the end of a long movie career spent giving nutcases unheeded advice in a mellifluous voice

3. Bette Davis, in a gray wig, but made up nicely and wearing chic clothes, showing that she still looked good if you weren’t deliberately trying to make her look bad

4. An impressive assortment of 1964 furniture and costumes (by Edith Head) and hairstyles, all deployed to tell a story that begins during World War II

5. Newspaper headlines which are used to remind the audience that though the hair may shriek 1964, V-J Day was back in 1945

6. Joey Heatherton as a brunette, and she spends most of the movie making day-at-the-dentist faces like that

7. Jane Greer in her standout supporting turn as “Recognizable Human Being.” (That's her in the middle, Joey's baring her teeth again on the right.)

Plus, Mark Harris recommended Where Love Has Gone on Twitter, and he wouldn’t steer a Siren wrong.

But...Lylah Clare. Jesus, what IS this movie? Many are the Robert Aldrich movies the Siren has seen and loved, but this one is no Autumn Leaves, hell, it’s not even Sodom and Gomorrah.

For one thing, Sodom and Gomorrah has a clear timeline. In Lylah Clare, the allegedly legendary title character was a German-born movie goddess who, while she was being chased by a lust-crazed fan who was threatening her with a knife, broke her neck in a fall off the building-code-violating banister-less side of the grand staircase of the home of the director she had married that day. (That’s the initial version discernible from one of many flashbacks, anyway.) Now, years later, Lylah's widower and director, Lewis Zarken (Peter Finch), is casting uncanny look-alike Elsa Brinkman (Kim Novak) in a Lylah Clare biopic, because Lewis wants a comeback, and everyone knows that biopics are the No. 1 fastest way to renewed artistic respect.

But: It’s apparently only 20 years, 25 max since Lylah met the mansion floor, and despite many flashbacks, this movie is set firmly in its late-1960s here-and-now. Not just the styles, but even the movie equipment, the cars, the TV sets, you name it. Yet in the slideshow of Lylah’s career that opens the movie, her “nude shot” echoes Marilyn Monroe’s last session with Bert Stern; Lylah’s wedding gown mimics bias-cut early ’30s; and the folks at Lylah’s funeral are wearing everything from a pillbox hat to a cloche. Later we also hear that Lylah slept with the Japanese gardener to console him on the eve of his being sent to an internment camp, which would make Lylah's neck still unbroken in 1942. Do you see that this math could give a person a migraine? Would you, like the Siren, spend much of the running time periodically yelling at the screen, “What the hell year is it?”

OK, given that the movie has a lot of other what-is-reality-anyway affectations, we’ll say it’s fine, and anyway, who doesn’t want to pretend that a few years here and there didn’t happen. That still leaves us with the script. Lylah Clare is supposed to be an excoriating look at the dream factory, well-trod territory for Aldrich (for the record, the Siren loves both The Big Knife and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?). Somehow Aldrich got the idea that what we want here is to have all of the philosophizing and negotiating played in a nice stable medium shot so you can’t miss a word no matter how hard you try, even when Rosella Falk (as Lewis’s lesbian housekeeper, who once loved Lylah) is compressing her lips in a straight line and giving one of her heavily accented speeches about what rats they all are. And what we want from the numerous flashbacks to old Hollywood, and Lylah’s tragic accident, and Lylah’s insatiable sex life, is a bunch of wavery black-and-white floating dream-insets with distorted sound.

There’s no humor in this movie. How can you have a movie about Hollywood without a single laugh? The closest it comes is Peter Finch’s line, addressed to Elsa as she tries to descend the staircase in an elegant manner: “We’re moving like a deeply offended Tibetan yak!” Which doesn’t make any sense, it’s just a collection of words, with royal first-person plural and Peter Finch’s accent used to simulate wit. And without even the saving grace of being funny, Peter Finch’s character is a trial: nasty, conceited, physically abusive, and vulgar, not so much Von Sternberg or Stroheim (supposedly the basis for Lewis) but rather the kind of man they satirized.

Ernest Borgnine is a one-note loudmouth, which, given that he is obviously playing Harry Cohn, lends a touch of historical accuracy, but gets old, fast. At least one of the screenwriters hated Hedda Hopper so much he invented a fictional leg amputation and prosthetic for the Hopper-based character, but even so, Hopper might have loved Coral Browne’s performance, especially because Browne makes her 10-minute scene one of only two good ones in the movie. The scene is a crowded cocktail-party-press-conference-star-unveiling sort of thing at Lewis’ mansion (where even the death of his wife still has not prompted Lewis to put a banister on the staircase). Browne’s gossip columnist pokes at Novak’s Elsa with her cane, and in a voice that would carry to the Old Vic balcony asks whether Elsa is sleeping with Lewis. And Elsa tells her off — in a heavily German-accented voice. Because Elsa is being possessed by Lylah.

The Siren has no problem with that plot development, matter of fact it was what drew her to the movie. But...when Elsa’s voice drops an octave and heads straight for Berlin (or as close a vicinity as Novak can get), none of the hundreds of guests say anything about that. And look, if out of nowhere you suddenly start doing your Marlene Dietrich impression, people say something. The Siren tells you this from personal experience.