Steven Lee Gilbert's Blog, page 2

August 16, 2012

Cleaning the Slate

Franca and I are not fanatics about health — well, our children might say we are and maybe it’s true, though we also believe that everything is better in moderation, including wellness dogmas — but we do eat well, exercise regularly and generally follow the kind of active, wholesome lifestyle that promotes youth, not aging. With this past year taking a toll on us on so many levels, in the days following our one year anniversary of living with diabetes we took advantage of this emotive milestone to do something about whatever remained of the unfavorable, pent-up feelings not successfully accepted, purged, exorcised or written off in the long months prior. There was, despite these efforts, the toxic residual of dark thought still polluting our minds and weighing our bodies down. I saw it when I looked in the mirror and felt it when I tightened my belt.

I didn’t know it then, but Eastern tradition has a word for this. It’s called amma. In English, we know it only as a mucus and while we don’t for the most part imagine it anywhere other than running from the nose, it’s everywhere in the body. The ears, the lungs, joints, the gut, the genitals. Our bodies make about a quart of it everyday in protecting these and other vital systems from such noxious intruders as pesticides, processed foods, medications, household cleaners and, according to believers of amma, negative emotions. Over time, the mucus builds up like plaque and leads to a feeling of lifeless and heaviness in the body and mind.

The solution to ridding ourselves of this unwelcome load, practitioners of this holistic movement say, is through treatments of a less conventional, more whole-person approach, such as nutrition, yoga, meditation, and fitness, all of which aid in this process of natural detoxification. One of the champions of this philosophy, Dr. Alejandro Junger, cardiologist and author of the book Clean, describes the goal as this: “the vibrant well-being and longevity that are your birthright.”

I had no idea if this was possible but I did like the idea of purging myself of the burden of what I could only imagine were the enduring spoors of every tear, every worry, every heartbreaking element of this new reality. The clarity and lightness I hoped to re-discover was just too much to pass up. Franca agreed and we borrowed Junger’s book from the library and, minus the supplements, adopted his nutritional cleanse program to help get us there.

The plan was simple: eliminate a number of foods from our diet — dairy, wheat, caffeine, alcohol, to name a few of my personal obstacles — and consume only liquid meals (smoothies, juices, soups) for breakfast and dinner; then allow at least 12 hours between dinner and breakfast to give the body time to digest the food and move on to the Great Toxic Dump.

We followed the program for two weeks — the full plan calls for three (everything in moderation, remember) — and to bring the kids into it and make it a bit more fun, we measured our success through the Ninentdo Wii Fit. By the two week’s end, we had shed a collective twenty pounds, most of which I can honestly say seemed to come not from fat but from somewhere deeper inside our bodies, giving some weight to the mucoid plaque theory. My Wii fit age dropped to 27 (I’m nearly twenty years plus that in non-Wii years, but in the interest of full disclosure, when we started I measured 31 Wii-years old, so not that great of a change. Franca’s age didn’t change at all, she held pretty much at 30). So it appeared from those reckonings alone to be a phenomenal success. But the real test however was not how I looked but how I felt and the clean did make me feel younger, healthier and more energetic, especially at night when before I looked ready for bed as soon as I’d polished off dinner, I now looked forward to a game of chess against Lia or even yoga with my wife.

As for the emotions? I won’t pretend to think that the anxiety I’d felt over the past year was suddenly and entirely eradicated with this cleanse. It wasn’t. After all, we’re talking about diabetes, an incurable illness requiring constant maintenance. Even with acceptance, each and every day adds some degree of grief, angst, and frustration to the volume of toxins for which mucus must keep up its insurgent-war against. What the clean did for me though is highlight the fact that you are what you eat, but you don’t have to be what you think.

Cleaning the Slate

This post was original published on my blog, Without Envy, January 19, 2011

Franca and I are not fanatics about health — well, our children might say we are and maybe it’s true, though we also believe that everything is better in moderation, including wellness dogmas — but we do eat well, exercise regularly and generally follow the kind of active, wholesome lifestyle that promotes youth, not aging. With this past year taking a toll on us on so many levels, in the days following our one year anniversary of living with diabetes we took advantage of this emotive milestone to do something about whatever remained of the unfavorable, pent-up feelings not successfully accepted, purged, exorcised or written off in the long months prior. There was, despite these efforts, the toxic residual of dark thought still polluting our minds and weighing our bodies down. I saw it when I looked in the mirror and felt it when I tightened my belt.

I didn’t know it then, but Eastern tradition has a word for this. It’s called amma. In English, we know it only as a mucus and while we don’t for the most part imagine it anywhere other than running from the nose, it’s everywhere in the body. The ears, the lungs, joints, the gut, the genitals. Our bodies make about a quart of it everyday in protecting these and other vital systems from such noxious intruders as pesticides, processed foods, medications, household cleaners and, according to believers of amma, negative emotions. Over time, the mucus builds up like plaque and leads to a feeling of lifeless and heaviness in the body and mind.

The solution to ridding ourselves of this unwelcome load, practitioners of this holistic movement say, is through treatments of a less conventional, more whole-person approach, such as nutrition, yoga, meditation, and fitness, all of which aid in this process of natural detoxification. One of the champions of this philosophy, Dr. Alejandro Junger, cardiologist and author of the book Clean, describes the goal as this: “the vibrant well-being and longevity that are your birthright.”

I had no idea if this was possible but I did like the idea of purging myself of the burden of what I could only imagine were the enduring spoors of every tear, every worry, every heartbreaking element of this new reality. The clarity and lightness I hoped to re-discover was just too much to pass up. Franca agreed and we borrowed Junger’s book from the library and, minus the supplements, adopted his nutritional cleanse program to help get us there.

The plan was simple: eliminate a number of foods from our diet — dairy, wheat, caffeine, alcohol, to name a few of my personal obstacles — and consume only liquid meals (smoothies, juices, soups) for breakfast and dinner; then allow at least 12 hours between dinner and breakfast to give the body time to digest the food and move on to the Great Toxic Dump.

We followed the program for two weeks — the full plan calls for three (everything in moderation, remember) — and to bring the kids into it and make it a bit more fun, we measured our success through the Ninentdo Wii Fit. By the two week’s end, we had shed a collective twenty pounds, most of which I can honestly say seemed to come not from fat but from somewhere deeper inside our bodies, giving some weight to the mucoid plaque theory. My Wii fit age dropped to 27 (I’m nearly twenty years plus that in non-Wii years, but in the interest of full disclosure, when we started I measured 31 Wii-years old, so not that great of a change. Franca’s age didn’t change at all, she held pretty much at 30). So it appeared from those reckonings alone to be a phenomenal success. But the real test however was not how I looked but how I felt and the clean did make me feel younger, healthier and more energetic, especially at night when before I looked ready for bed as soon as I’d polished off dinner, I now looked forward to a game of chess against Lia or even yoga with my wife.

As for the emotions? I won’t pretend to think that the anxiety I’d felt over the past year was suddenly and entirely eradicated with this cleanse. It wasn’t. After all, we’re talking about diabetes, an incurable illness requiring constant maintenance. Even with acceptance, each and every day adds some degree of grief, angst, and frustration to the volume of toxins for which mucus must keep up its insurgent-war against. What the clean did for me though is highlight the fact that you are what you eat, but you don’t have to be what you think.

August 14, 2012

A Lesson on Atoms(or Letting Go)

When it was early summer vacation and close enough to the end of the school year for Lia to still be considered an elementary student and not a rising sixth grader Franca and I weren’t sure what changes we’d make to her diabetes care plan to meet whatever new challenges arrived with middle school. Other than a few frustrating moments—a teacher withholding candy for some asinine reason, the immaturity and arrogance of young boys, chaos around the lunch bolus—school and her diabetes for the most part had gotten along. At least there were no panicked drives across town or phone calls that made us question why in hell we weren’t home schooling (not that had to do with diabetes anyway).

In fact, Lia’s school does a pretty good job of making us both feel like we’re not wasting our time sharing with them—sometimes more than once—facts about highs and lows, helpful tips for teachers of students with diabetes, unique details of Lia’s own treatment and management of her disease. They appear interested, concerned. They ask questions for clarification, offer personal testimony and eye witness to Lia’s strong character, her stoicism, her quietude and composure. By their words, or mostly with just their silence, they acknowledge this one true thing: In terms of diabetes, Lia is in charge.

It’s a question of independence and one that her mother and I were, and still are and will be for many years to come, struggling with as we sat down and talked about the upcoming school year. To understand why you must first have a child and then that child must get sick and be diagnosed with an illness for which is there no cure. Only then will you understand a parent’s worry of letting go. There is no other training for this, no software simulation that will help you understand. And, as I’ve alluded, children with diabetes make taking care of it look like a breeze. Poke. Test. And Bolus. Move on. Next lesson, please.

I’d like that to (but it won’t) help you appreciate our routine for the past couple of years which has been for Lia to call from a phone in the classroom, or the office, if necessary, and talk with one of us about her blood sugar before she does any bolusing. Same with lows. Call, then correct, or correct if you have to but give us a call right after. Because there is no school nurse, it’s just what we had to do. It’s what made us feel safe, because we were in charge, not Lia.

With age comes change however. Like atoms, of which humans are made up of many (about 7,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000), diabetes is not something that can be divided. We cannot take some, say just the parts of it that keep her safe and sound, and leave the rest for Lia (those parts that let her cut in line if she has to pee, or drink juice during English class). As she gets older she’ll gradually assume more and more of the whole until there is nothing but worry and hope that is left for her mother and father. I don’t like it and would do anything to change it, but it is what it is. I can’t fight it. But what we give up we give up in the smallest of increments.

Already Lia is showing signs of her readiness—wrong word. Surrender, perhaps is more fitting—to take on more. So for middle school we’re giving her a new tool to help her succeed, but at the same time still keep us informed. With a cellphone, she’ll no longer have to endure phone calls standing in the doorway next to the hall, where kids are pushing and shoving past, jockeying in the way kids do, while trying to share with with me her blood sugar number. She’ll no longer have to take time out of her measly lunch period fielding questions from me that usually start with: So, how’s it going? As if I forgot she’s at school, and not a sleepover at Grandma’s.

Now—she’s been back to school for four weeks—she texts us from her seat. Before or after she eats, sometimes not at all, but those rare occasions we remind her of our expectations. She texts us, too, if she goes low and has to correct. She texts us other things as well—”Can BB (her friend) come over.”—but mostly she keeps her messages on topic, so she can get back to the things that a middle schooler finds important, like how in the world did anyone ever arrive at a number with twenty-seven zeroes. Okay, maybe that’s not exactly important, but it is, at least momentarily, a bit mind-boggling. Which will likely for her and most others pretty much sum up middle school.

July 23, 2012

Guest Post: A Lovely, Anti-Hero

This weekend I had the opportunity to write a guest post at Guiltless Reading, an exceptional blog from a writer based in Canada. Also included is a giveaway, both a signed paperback and an eBook edition up for grabs to those to enter. So click on over to Guilltess Reading and read what I have to say about writing a book that begs the reader to root for the anti-hero (okay, she’s not nearly as bad as Snake Plissken).

June 23, 2012

Inspiration: For When You Need It Most

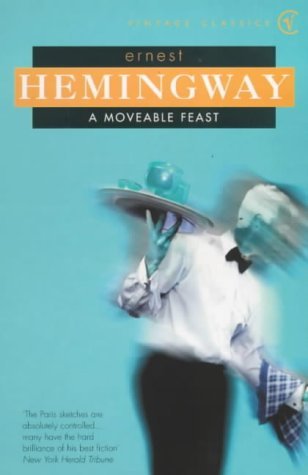

I don’t even own this book, but for some reason it is always there on my mind or in the back of my mind or otherwise someplace near to it. When I check it out of the library, I usually keep it through the maximum amount of renewals (9 I think) and thumb through it almost daily, reading bits and pieces of it here and there, discovering something new every time, and not just about Paris, or Hem, or that era, but amount myself and how I choose to view the world. Having written that just now, it sounds heavy, I know, but trust me it’s not. It’s actually quite simple and down-to-earth.

I can’t remember what drew me to A Moveable Feast the first time I read it—it was probably at my wife’s suggestion, but I do know it was on my writing desk the day my daughter was diagnosed with the autoimmune disorder, type 1 diabetes. Obviously there was no connection to Hemingway’s Paris and this affair—we live in the American south and there was no drinking, no horse racing, no boxing or famous people involved—but I found nonetheless something buoyant about the writing itself that helped me come to grips with this, our own life-changing event.

Shortly after the diagnosis, I began writing this blog and what Hemingway’s writing of Paris, and his other, fictional work, too, of course, but Paris was real, what it taught me was to identify the emotion, find it in whatever action or person that gave it to you and write it down in such a way that it’s honest and clear so that if any one else reads it they will see and experience the same emotion too. It set a perfect example for a father who was facing what is and will probably be one of the saddest, most painful situations in his life, if only because of how unprepared and little I knew about it. For as Hemingway once wrote himself: The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong in the broken places —A Farewell to Arms, so too had the world, it seemed, broken me and those I loved, but through writing about it I felt stronger. You can’t ask much more from a book or its author.

Originally posted on my Goodreads Q&A

Inspiration: For When You Need It Most

I don’t even own this book, but for some reason it is always there on my mind or in the back of my mind or otherwise someplace near to it. When I check it out of the library, I usually keep it through the maximum amount of renewals (9 I think) and thumb through it almost daily, reading bits and pieces of it here and there, discovering something new every time, and not just about Paris, or Hem, or that era, but amount myself and how I choose to view the world. Having written that just now, it sounds heavy, I know, but trust me it’s not. It’s actually quite simple and down-to-earth.

I don’t even own this book, but for some reason it is always there on my mind or in the back of my mind or otherwise someplace near to it. When I check it out of the library, I usually keep it through the maximum amount of renewals (9 I think) and thumb through it almost daily, reading bits and pieces of it here and there, discovering something new every time, and not just about Paris, or Hem, or that era, but amount myself and how I choose to view the world. Having written that just now, it sounds heavy, I know, but trust me it’s not. It’s actually quite simple and down-to-earth.

I can’t remember what drew me to A Moveable Feast the first time I read it—it was probably at my wife’s suggestion, but I do know it was on my writing desk the day my daughter was diagnosed with the autoimmune disorder, type 1 diabetes. Obviously there was no connection to Hemingway’s Paris and this affair—we live in the American south and there was no drinking, no horse racing, no boxing or famous people involved—but I found nonetheless something buoyant about the writing itself that helped me come to grips with this, our own life-changing event.

Shortly after the diagnosis, I began writing a blog—feel free to follow this link to visit it, it’s called Without Envy—and what Hemingway’s writing of Paris, and his other, fictional work, too, of course, but Paris was real, what it taught me was to identify the emotion, find it in whatever action or person that gave it to you and write it down in such a way that it’s honest and clear so that if any one else reads it they will see and experience the same emotion too. It set a perfect example for a father who was facing what is and will probably be one of the saddest, most painful situations in his life, if only because of how unprepared and little I knew about it. For as Hemingway once wrote himself: The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong in the broken places —A Farewell to Arms, so too had the world, it seemed, broken me and those I loved, but through writing about it I felt stronger. You can’t ask much more from a book or its author.

June 22, 2012

A Guide for Readers

I have been fortunate in the three months since launching the book to participate in a number of writing discussions, interviews, readings, forums, etc. A pleasant surprise from those experiences is the degree of thought and introspection it required of me to answer certain questions about the novel. That sounds strange since I wrote it—and perhaps it may just be a matter of me needing to offer up something better than, Just because to answer why I omitted quotation marks or chose not to translate the Italian—but these questions encouraged me to dig deeper into the how I told the story and not just what the story was about. And honestly, it was just great fun, like being a student again in a way.

Back when I was a student, however, time spent pondering over the many symbolic interpretations of style, device, or storytelling seemed wasted to me and was often a discussion I always felt inadequately prepared for in class—as if I had read some entirely different passage than everyone else. I could not get past the perceived futility in trying to guess, for instance, whether or not in writing about a great white whale, the author (Melville) was actually writing about elusive goals, or was it to him just a fishing story of the one that got away (not likely).

But now having written a couple of novels of my own, I can appreciate these discussions with greater understanding and appreciation for the idea that it’s not only possible but probable that the author them self could not have grasped all of the supposed symbolism in their work. And that actually makes perfect sense to me. How often are we met in our daily lives with moments that mean something more to us simply because we can relate it to a greater whole. Often, right. I believe it’s that way with writing a novel, too. Writers are working hard to present this perfect vision they have in their minds, sentence by sentence, scene by scene, and it is only after they are finished that they can step back and put some distance between those various parts and look at the whole to visualize how they connect to one another, even something as un-relatable as choosing to not translate a foreign language, or the omission of quotation marks.

One of the most difficult things of growing old is the regret for not doing or being something different than who we were. I enjoy talking about literature and books and contemplating how they make you think and relate the story in someway to your own life, your own tiny piece of humanity. Those days sitting in a classroom would not be wasted, for sure.

This rambling on does have a point and it’s this: As in most literature, after reading this book there will be questions that arise. What happened after? Before? Why this and not that? And so on and so forth. I could give my perspective as the author, and have before, but some of the pleasure and purpose to reading is to relate this world to your own, to discover and share in some common ground. To force the deeper question. With that in mind I’ve spent the last few days putting together a Reader’s Guide for the novel. You can find it to the right of here, just click to download. It, too, may be a work in process as ideas come to me about the book, but if you’re interested in connecting with the story in a more meaningful way, I hope it will serve as a good start.

June 20, 2012

On Becoming A Writer

The story of how I came to want to be a writer is not unlike any others. I was drawn to it, almost as if by accident, through some other passionate interest. I was in the eighth grade and at that time—and still now—I was very much into the responsible use and protection our natural resources. I liked camping, hiking, and just generally being outdoors and if asked would have named some mountain, desert, river or coast as the place I most wanted to visit. One day, my English teacher, a lady of which I remember very little about but who apparently believed it her job (rightly so) to help children discover their potential, suggested I enter a youth essay contest on why it was so important that society protect these natural resources. I entered the contest and won.

We all know that sometimes it takes someone else pointing out a talent to make us aware of it ourself and this is what happened to me with writing. I discovered not only that I liked it, but if I was passionate and wrote truthfully about a thing I could make the words mean something to someone else. From that moment on I felt encouraged, excited and even entitled, in some respect, to write.

But as it goes, talent take time to develop. And it also takes work. One of the most important aspects to the process though is that you write about something you care about or the talent to make others see what you see and feel what you feel will be lost. Recognition can work against you, too, giving the false impression that anything you write will be received well, which is just not so. In choosing to write about child custody, I was choosing a topic I was very close to personally, at least in terms of my witness of a hotly contested case. I, too, have loved and lost and been unjustly misunderstood.

Even then, the novel took several years to write, time partly and intermittently spent discovering the way in which how to tell the story and then on the story itself. There were many stop and goes, dead ends, and detours, but with each of these I felt I was steadily getting closer to the heart of the novel, even when not working on it, even in my darkest days of which I won’t go into here, but evolved into months and years when writing fiction felt like a violation of parental responsibility. The hard part is pushing through these and remaining committed to telling the truth, which is what Hemingway once said, was the writer’s job anyway.

It was no accident that Anna Miller lost child custody, nor was her son’s kidnapping accidental. Strong intention can and often does level the playing field. But without action intention serves little or no purpose. For an early lesson in that, I have an eighth grade English teacher to thank.

To follow the discussion on my Goodreads Question and Answer, click here.

June 19, 2012

Appearances Matter (From my Goodreads Q&A)

One of the most important aspects of the novel is the notion (reality) that people have a public image that is different from the private self. In the book I don’t elaborate on the circumstances surrounding how Evan Meade got custody of Oliver because those circumstances don’t really matter. He did. And he shouldn’t have. The first is in the past, the onus of the showing why it was wrong falls to the book through character development.

The reason I chose not to explain the custody in greater detail was to illustrate what I believe to be the ludicrous notion that judges make decisions everyday about kids and custody knowing full well that the testimony they hear is tainted with these two sides of a person’s identity. This book, as in real life, attempts to dole out bits of their personality slowly and relies upon the intuition of the reader to fill in some of the blanks themselves just in how the characters behave. That is precisely, I feel, how real life works. Nothing is given to us on a platter. We intuit people, we watch and listen and read between the lines to learn who they really are. To do or expect something different in this story would be to not reflect real life.

The question of how much an author must fill in for the reader so as not to make character development a hardship on them is one of the most difficult aspects of writing a novel. You worry that what you omit will leave the characters not fully developed and the reader then not fully satisfied. But the flip side of omission is inclusion and adding more to the story than is needed means there is nothing then for the reader to contemplate on their own, to think through and work out, to discover, which, I believe, is the true pleasure and purpose of reading.

June 6, 2012

Fix. It.

Not quite related to diabetes care, management, complaints of, progress in, fed up with, tears over, yada yada yada….but I think this relates to my recent post Hulk Smash, in which I reflected on my inability to fix things.

Annie Leonard’s project The Story of Stuff has always counted Franca and I as two of their biggest fans—we love the idea of Reduce, Reuse, Recycle and now this, her latest venture in responsible consumerism: Repair. Give a listen as she talk to the folks at Ifixit.org and instructables.com and maybe it will invigorate you, too, to think about how you fix something when it breaks BEFORE you buy it, or going when step further, how to make it yourself.

The Good Stuff — Episode 4: Fix it, don’t nix it!

Steven Lee Gilbert's Blog

- Steven Lee Gilbert's profile

- 61 followers