ريتشارد دوكنز's Blog, page 657

October 23, 2015

Dog Wearing GoPro Is Attacked By Wolves

Photo credit:

Swedish Elkhound (not the dog in the video below). Robert Nyholm/Shutterstock

Moose-hunting season in Sweden comes with the inevitable dangers that such forested regions hide. In a distressing video, a dog wearing a GoPro captures the moment two wolves attack her while on a hunt with her owner.

Humanist group: Rankin Co. teacher ridiculed atheism

File photo/The Clarion-Ledger

By Anna Wolfe

A new complaint suggests the Rankin County School District has again muddied the line that separates church and state.

The American Humanist Association’s Appignani Humanist Legal Center says an unconstitutional promotion of Christianity has continued in the district.

On Oct. 13, the association sent a letter to district officials and attorneys describing an alleged incident involving a teacher at Northwest Rankin High School mocking atheism in the classroom.

Sent on behalf of an atheist student, the letter says her teacher, who is also a pastor of a church, told the classroom on Oct. 8, “Atheists are throwing a fit because they don’t have their own day. They do have their own day; it’s called April Fools’ Day, because you are a fool if you don’t believe in God.”

Read the full article by clicking the name of the source below.

Hurricane Patricia Rapidly Becomes Strongest Storm Ever in Western Hemisphere

In the past 24 hours Hurricane Patricia, bearing down on Mexico’s west coast, has rapidly intensified to become the strongest storm ever recorded in the Western Hemisphere. As of this morning, data from Air Force planes show peak winds (sustained for one minute) of 200 mph and a surface pressure bottoming out at 880 millibars (typical pressure at sea level is 1013 millibars). The numbers push Patricia past the former record holders: Hurricane Wilma in 2005 and Hurricane Gilbert in 1988.

On Friday morning the National Hurricane Center said Patricia’s winds could rise to 205 mph as it hits Mexico’s shores, which would be the highest landfall reading ever, worldwide. When “super typhoon” Haiyan struck the Philippines in 2013 winds were 195 mph.

In contrast, the lowest pressure reading (the real measure of intensity) for Katrina, when it peaked in the Gulf of Mexico before drowning New Orleans, was 902 millibars. The low point for Sandy, which clobbered New York City and New Jersey, was 940. It is important to note that the extreme readings often occur when storms are still at sea, and frequently lessen before landfall—although that may not be the case for Patricia. Katrina’s top winds when it crossed the Gulf Coast were 125 mph, and when Sandy landed on New York City winds peaked at 94 mph.

Here, then, are the numbers for the Western Hemisphere’s strongest and most infamous hurricanes:

Patricia (2015): Top wind speed 200 mph; lowest atmospheric pressure 880 millibars. Threatening Mexico West Coast.

Wilma (2005): Top wind speed 185 mph; lowest atmospheric pressure 882 millibars. Struck Yucatan Peninsula and Florida.

Gilbert (1988): Top wind speed 185 mph; lowest atmospheric pressure 888 millibars. Struck Caribbean, Yucatan Peninsula, Texas.

Katrina (2005): Top wind speed 175 mph; lowest atmospheric pressure 902 millibars. Struck Gulf Coast.

Sandy (2012): Top wind speed 115 mph; lowest atmospheric pressure 940 millibars. Struck U.S. East Coast.

For more on hurricanes see our In-Depth Report.

A Fossil Find Gets Entangled with South Africa’s Apartheid Past

The finding last month that a group of fossils from a cave not far from Johannesburg belongs to a previously unknown human ancestor would appear to cement South Africa’s status as one of the world’s leading hotspots for research on human origins. But it also provoked a backlash from a few influential national figures who associate the finding with five decades of apartheid governance.

A paper in the journal eLife last month that pegged Homo naledi as a new member of our genus Homo prompted a leader on the South African political scene to engage in a muddled questioning of the theory of evolution and a denial that humans were in any way related to other primates. The comment provoked a flare-up that highlights the still-open wounds from the country’s apartheid’s past. Blacks during the apartheid era were often depicted, even in the universities, as less than human. (Scientific American is part of Nature Publishing Group.)

The spat began when trade unionist Zwelinzima Vavi tweeted: “No one will dig old monkey bones to back up a theory that I was once a baboon.”1 South African Council of Churches President Bishop Ziphozihle Siwa concurred: “To my brother Vavi, I would say that he is spot-on. It’s an insult to say that we come from baboons.” The interdenominational council, which unites 36 churches today, played a major role in the anti-apartheid struggle when it was led by the likes of Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu. Siwa’s words were echoed by African National Congress politician Mathole Motshekga who said “… it is offensive that the findings made are used to say that we are the descendants of baboons, because we are not.”

In responding to these remarks in press accounts, Lee Berger, lead researcher on the H. naledi study, explained that humans do not descend from baboons. Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins jumped in, tweeting back: “Whole point is we’re all African apes.” All living humans, regardless of race, are members of Homo sapiens, a species that originated in Africa and is ultimately descended from a common evolutionary ancestor shared with African apes.

The sentiment deriding H. naledi was by no means universal; most South Africans expressed great pride in the finds. Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa, according to one local news report, said that H. naledi proves that “the Cradle of Humankind [the area where the fossils were found] is the umbilical cord of our humanity.”

The reaction by these South African public figures, and the social media storm, can be better understood in the context of apartheid’s persistent legacy. “A lot of Africans have some suspicions of scientific ideas, especially evolution,” says Zinhle Mncube, an associate lecturer in philosophy at the University of Johannesburg. “Craniology, phrenology, eugenics; they were all used to justify the idea of the African as subhuman.”

These pseudosciences of the 19th- and early 20th-century were a “foundational moment for the colonial project,” says historian Noor Nieftagodien, head of the History Workshop at the University of the Witwatersrand. “According to the social Darwinism of that era, the pinnacle of evolution was the blonde, blue-eyed man with the blonde, blue-eyed woman just beneath him and the colonial subject at the bottom of the heap.”

During the apartheid era, some prominent white churches also “mobilized to support the claim of black inferiority,” says Nieftagodien, an uneasy partnership that created a powerful and remarkably persistent ideology. To this day, the pejorative bobbejaan (baboon) is still used by some South Africans.

The white-man-at-the-top hierarchy left a deep impression in the minds of many Africans. Nowhere has the damage been as profound as in South Africa, colonized for more than three centuries and dominated by apartheid’s white minority government for 50 years.

Even today, two decades after apartheid rule, South Africans still receive reminders that the apartheid dogma of black’s racial inferiority was promulgated even in the universities. In 2013 a doctoral researcher in anthropology at Stellenbosch University found a human skull, glass eyes and hair color charts in a storage cupboard; these turned out to be tools developed by Eugen Fischer, the eugenicist who inspired Nazi theory, and were used to teach volkekunde (an apartheid form of cultural anthropology)—a stark demonstration of how the trappings of science were used purposefully to underpin and reinforce the idea of racial inferiority that linked black Africans with apes.

Bringing these effects out of the closet spurred the founding of a project called “Indexing the Human,” led by Steven Robins, a professor in the Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology at Stellenbosch. It aims to explore deeply-held assumptions by society and academia, emerging from the historical context of colonialism, about what it is to be human in South Africa and the Global South.

The experience of being treated as the relatives of apes and monkeys could explain why, as Mncube notes, this gut rejection to the link with H. Naledi tends to come from older rather than younger people. But young South Africans have not escaped the sting of these old wounds entirely. The current student protest movement that started with the slogan “Rhodes must fall” at the University of Cape Town seeks the decolonization and transformation of South Africa’s academic institutions. The statue of British imperialist Cecil John Rhodes at the university was seen as symbolic of the Western bias of academe—and was ultimately removed.

The response to H. naledi shows an unfamiliarity with the science that ultimately overthrew the racist pseudosciences, Nieftagodien says. Evolution is poorly taught, if at all, and little understood, Mncube adds—so people fail to see that the fossil finds support a common origin for all humankind and debunk the concept of races. “If scientists listen to what people actually know, they will understand the need for ongoing education projects that explain key concepts like evolution,” she notes.

October 22, 2015

This Woman Can Smell Parkinson’s Disease

Photo credit:

Ocskay Mark/Shutterstock

The thought of being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease strikes fear into the minds of all but the most stoic individuals; early detection is difficult, and it is currently an incurable condition. So it is quite astonishing that Joy Milne, a 65-year-old woman, has the ability to “smell” the disease in people, as reported by BBC News.

Making Dinosaurs Awesomer

Last week, on National Fossil Day, our Stephanie Keep organized a twitter conversation where folks could ask paleontologists their pressing questions. It rocked, and you can find the whole thing on the #askapaleo Storify.

Stephanie’s icebreaker question about the disappointingly featherless dinosaurs in Jurassic World got this reply from paleontology reporter Brian Switek:

A2: @keeps3 @TomHoltzPaleo But I would've loved to see #JurassicWorld depict the awesomeness of dinosaurs as we know them now #askapaleo

— Brian Switek (@Laelaps) October 14, 2015

I thought about that again when I saw this video today, in which paleoartist Josh Cotton fixes the Velociraptors from the first movie:

Jurassic World’s producers claim part of the reason they didn’t put feathers on their dinosaurs was to keep them scary, but seriously, I would not want that feathered beast chasing me. Nor does the excuse make sense that featherless dinosaurs are more familiar. We’ve known about dino feathers since the late ‘90s, and known they were quite common since at least the middle of the ‘00s. The young audience targeted by the latest film grew up with feathered dinosaurs, and the dinosaur superfans who adore the Jurassic Park franchise know that dinosaurs had feathers, too.

It’s uncanny how much more we know about dinosaurs now than we did 25 years ago, when Jurassic Park was filmed. And even then, it was remarkable how much we knew (or could reliably infer) about dinosaurs and their behavior. It was disappointing that the latest movie didn’t carry on the original’s commitment to incorporating the best modern science (and that the script didn’t measure up), but it was still quite a spectacle.

The progression you see in Josh Cotton’s video is pretty spectacular, too. It’s a testament to science that, where once the colors of dinosaurs were a matter of pure imagination, we now can recover remnants of pigment from fossilized feathers and know what color dinosaurs were. There are other changes that have happened in those years, refinements of our understanding of how dinosaurs stood and moved.

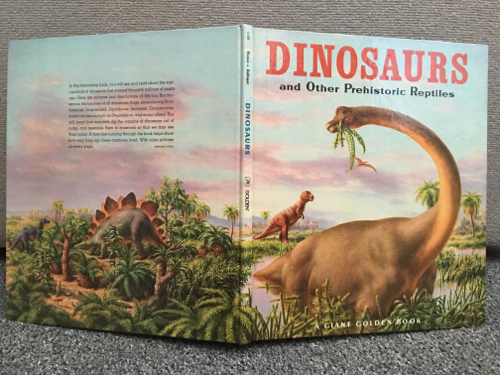

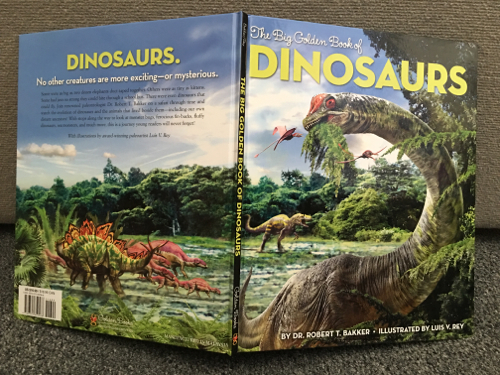

Compare the covers of my childhood copy of Golden Book’s Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Creatures (copyright 1960, my version was published in 1982, cover art by Rudolph Zallinger) to 2013’s The Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs (cover art by Luis Rey). Sure, the new dinosaurs have color and texture, but look also at how the Tyrannosaurus holds its head low and its tail in the air. The Brachiosaurus is on land, not in the water. And on the back cover in 2013’s book, a vibrant Stegosaurus rears up on hind legs and a herd of hadrosaurids (Edmontosaurus, I believe) race across the field, in contrast to the staid stegosaur and Trachodon (a genus of ) in the 1960 version.

Compare the covers of my childhood copy of Golden Book’s Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Creatures (copyright 1960, my version was published in 1982, cover art by Rudolph Zallinger) to 2013’s The Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs (cover art by Luis Rey). Sure, the new dinosaurs have color and texture, but look also at how the Tyrannosaurus holds its head low and its tail in the air. The Brachiosaurus is on land, not in the water. And on the back cover in 2013’s book, a vibrant Stegosaurus rears up on hind legs and a herd of hadrosaurids (Edmontosaurus, I believe) race across the field, in contrast to the staid stegosaur and Trachodon (a genus of ) in the 1960 version.

This constant revision is a feature of science that is both marvelous and sometimes troubling. That willingness to refine our claims in light of new evidence, and the ability to apply new tools to derive new insights from old bones, is a source of tremendous power. But creationists and other science deniers are fond of using such revisions as evidence that science is unreliable, shifty even. And they point to honest admissions of scientific ignorance (like older texts which proclaimed the color of dinosaurs to be unknowable) as proof that science is incompetent, without acknowledging the remarkable progress science has already made.

A Strong Work Ethic Brings Sick Doctors to Work

There’s an ironic trend in the medical field: Health care workers often come to work while they’re sick themselves, endangering colleagues and patients. Although researchers have worried about the health implications of this trend for roughly five years now, two new studies have finally targeted whysick health workers are continuing to come into the office and offer potential solutions.

In a study, published in JAMA Pediatrics last month, Julia Szymczak from The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and her colleagues surveyed 536 hospital workers. They found that roughly 83 percent of the health care personnel admitted to working while sick at least once in the past year—despite the fact that 95 percent thought it would put their patients at risk. “We know that this happens in all types of work environments,” says study co-author Julia Sammons, medical director of the department of infection prevention and control at CHOP. “In health care certainly the concern is that in the course of coming to work we are interacting with patients who themselves are sick and may be vulnerable.”

In targeting the reasons why personnel continue to come in sick, the team found that above all else it is health care workers’ strong dedication to colleagues and patients. “If you are a clinician who has scheduled an appointment for a particular patient four months ago and that patient is traveling from far away to see you, you don't want to let them down and cancel that appointment,” Szymczak says. This strong work ethic, Szymczak thinks, is part of the health worker identity. But when the problem runs to the very core, how do you find potential solutions?

Shruti Gohil, an associate medical director of epidemiology and infection prevention at the University of California, Irvine, Medical Center, and her colleagues might just have the answer—or at least a step that will bring them closer. “It seems like our health care workers are hungry for some careful guidance,” Gohil says. In a new study presented last week at IDWeek 2015, a meeting of several organizations focused on infectious diseases, the team reported they found 99 percent of medical workers would respond to various types of interventions.

According to Anupam Jena, an associate professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, both studies lack convincing evidence. “It's true that if you have a doctor working with infectious symptoms, other doctors or nurses could be affected—but the extent of the problem is really not known,” he says. “When a sick doctor works in a medical unit, exactly how many patients get sick? We really don't know.” And Jena is concerned that without hard core evidence, health workers will be hard-pressed to change.

Still Gohil remains hopeful. She draws on an example in 2011 when another drastic change rippled through the medical field: The number of hours physicians are permitted to work. Interns, for example, are no longer allowed to work more than 16 hours a day. Before this mandate it was common for an intern to work 24-hour shifts. Gohil thinks if that cultural transformation occurred, there’s no reason why this one can’t.

Indeed Szymczak and Sammons have already introduced a pilot program within the Department of Pediatrics at CHOP. It puts in place some basic guidelines to begin to tackle the problem, like having a point of contact when doctors or nurses are sick. This relieves individuals of finding their own replacement. “We want to keep moving the dial,” Szymczak says. “Intervention is really the next step for us.”

But the specific steps forward will depend on the institution at hand. “I don't think that the solution to this is a one blanket rule that says your institution should do X to fix this problem,” Szymczak says. “It involves local, adaptive work to say, ‘What are the challenges at our institution in these different clinical areas, What's the culture of our institution?’” So each hospital will have to analyze the reasons sick workers are not staying home in order to find a solution. At CHOP, for example, a strong work ethic seems to be the most salient reason but staffing concerns are a close second. Roughly 99 percent of the medical workers surveyed did not want to let their colleagues down, 95 percent worried about finding colleagues to replace them in their absence, 92 percent feared their colleagues would ostracize them and 64 percent were concerned about the continuity of care for their patients.

Jena’s own research in 2010 echoed the second finding. He and his colleagues found that residents with more experience were more likely to report they worked while sick than did those with less experience. Although Jena’s research did not probe the exact reasons, he suspects staff in more senior positions are less substitutable. He likens a hospital setting to any regular company where it is harder for managers to call in sick because a lot of work flow depends on their input.

The same is true in smaller clinics. “If you're a primary care doctor and it's just you in the practice, then who is going to cover for you?” Jena asks. “Who is going to see those 40 patients you have scheduled that day?” For these doctors, it's extraordinarily difficult to not come into work. All experts agree that in this case, doctors should at least wear the appropriate protective gear and take extra precautions.

At the end of the day, even Jena, who worries that without hard evidence dramatic change will be difficult, remains hopeful. “You just have to rely on the compelling logic that if you have flulike symptoms you're likely to pass that on,” he says. “It's not scientific but it makes good sense.”

The Universe Really Is Weird: A Landmark Quantum Experiment Has Finally Proved It So

Photo credit:

Deep seabed mining for minerals might soon become a reality. Nautilus Minerals/AAP

Only last year the world of physics celebrated the 50th anniversary of Bell’s theorem, a mathematical proof that certain predictions of quantum mechanics are incompatible with local causality. Local causality is a very natural scientific assumption and it holds in all modern scientific theories, except quantum mechanics.

Women Preferred For STEM Professorships – As Long As They’re Equal To Or Better Than Male Candidates

Photo credit:

How much do hiring decisions in academia factor in the gender of the applicant? Files image via www.shutterstock.com.

Since the 1980s, there has been robust real-world evidence of a preference for hiring women for entry-level professorships in science, engineering, technology and math (STEM). This evidence comes from hiring audits at universities. For instance, in one audit of 89 US research universities in the 1990s, women were far less likely to apply for professorships – only 11%-26% of applicants were women.

Creepy And Fascinating Video Of A Black Window Spider Molting

Photo credit:

Macropod/Rumble

Rumble user Macropod has uploaded a video of a black widow spider molting that is simultaneously fascinating, compelling and creepy.

ريتشارد دوكنز's Blog

- ريتشارد دوكنز's profile

- 106 followers