Everett Maroon's Blog, page 6

September 8, 2014

How HRC Is Botching Its Apology to Trans People (Part 1)

Late last week HRC President Chad Griffin offered a keynote speech at the Southern Comfort transgender conference acknowledging his organization’s failure to support the transgender community and its history of obstructionism (see here, here, and here) against trans civil rights. I and others called it a problematic apology, because he seemed to couch his understanding of HRC’s mistakes as one of simply not knowing enough about us (which has not always been the issue), and he framed his new approach in a paternalistic way, instead of asking us what HRC should be working on or how they can help.

People in the LGBT movement have for years been wondering amongst themselves just what will happen when the infrastructure that has been set up (to funnel money into the same-sex marriage movement) doesn’t need the same focus anymore. Will the donors move their money to a new issue? Buy yachts and celebrate the institution of marriage? Fund political campaigns?

I’m not here to argue about whether HRC is anti-trans or not (I’ve certainly made my views clear), not in this post, anyway. Instead I’d like to point out that Mr. Griffin’s idea that HRC will include trans-specific protections in the next anti-discrimination omnibus bill is far, far from what transgender and transsexual and gender non-conoforming people need, as civil rights movements go. Nobody is against anti-discrimination bills, especially if they include “gender identity or expression” as part of their protected classes, but it’s too easy for LGB activists to throw that clause in there without a real understanding of what protections for trans folk would look like. Well, let me ask us to reframe these considerations, in this way:

Let’s look at the trans person’s life cycle, from cradle to grave. What might we need to support our lives and experience that cisgender people would never need?

1: Childhood—In part because trans people have been more visible in the last generation, today’s children more often understand themselves as trans and ask the people nearest them (read: their parents and teachers) for support. A public policy for supporting trans kids would do some or all of the following:

Offer trans-supportive mental health/social work services for trans kids so they have objective partners in their process

Offer family support through identification of a trans identity (because you know, parents don’t automatically support their trans kids or know how to) into and through transition (if that is what the youth wants)

Educate school systems, administrations, and teachers to provide a hostility-free learning environment for trans children, including using a child’s chosen name even if that name is not their legal name

Readily identify trans-related bullying and help trans youth find alternative paths toward a high school degree if their primary school becomes an untenable place to learn

Ensure that after-school and extracurricular activities are trans-friendly and accessible to trans youth

Change rules around school sports to ensure than trans children can participate in a way that comports with their gender identity or expression

Modify existing law around custodian care so that if only one parent is supportive of a trans child, they can still help direct their care and services

Relax rules around emancipated minor laws for older trans teenagers who may need to leave their parents’ home

Train crisis care counselors, suicide hotline managers/call centers, and any local government-run mental health care workers in trans issues so that they are culturally competent

Educate physicians on hormone blockers, hormone therapy for adolescents, and the medical needs of trans youth

Change laws so that trans-related care is included in health insurance policies

Train youth homeless shelter staff in trans issues so that they are culturally competent

Enforce rules changes with a resource/response board to hear complaints and advocate for trans youth

2: Adulthood—Many trans advocates are already agitating for many (if not all) of these things to improve our lives, and they often do their work without the platform of someone like Janet Mock. Frustratingly much of this work has been done on a jurisdiction by jurisdiction basis because, in part, of HRC and its past obstructionism (ENDA, anyone?). But in truth the needs are far more comprehensive than what has been wrangled at the national level. Here’s at least some of what we need:

Anti-discrimination law at the federal level that includes housing, employment, and education

Full clarification (we’ve already gotten some but it’s still a gray area) that trans college students are protected under Title IX

Change federal law to prohibit transgender exceptions in health care insurance coverage; coverage for trans-related health care up to and including trans-related surgeries

Train first responders, police officers, fire fighters on trans issues so that they are culturally competent

Require that public spaces be trans-supportive, especially including public restrooms. This can be done in many ways, including creating gender neutral rest rooms or making all restrooms unisex.

Require that public spaces that have an expectation of nudity (homeless shelters, locker rooms) offer a trans-supportive space or be otherwise open to trans people using them

Create federal rules for treating trans prisoners with dignity and respect (more about this tomorrow in Part 2)

Define what constitutes anti-trans harassment, such as intentionally misusing someone’s name or pronouns, so that they have grounds for a grievance or remediation in their situation

Repeal any law that automatically invalidates a marriage because one of the partners transitions, and stop using transition as a legitimate ground for annulment in court

Ban transition and gender identity or expression as a justification for a parent to lose custody or visitation of a legal dependent

Support job training and placement programs for trans young adults and adults

3: Senior Citizens—Give us a few more years and we will hear more stories about what’s wrong with our country’s already inadequate senior support services. Nursing homes, assisted living centers, retirement communities all have a long way to go before they are truly supportive of older trans people who need extra care and can no longer live at home. Here’s my start of a list:

Require that all care be given in support of the individual’s gender identity or expression

House trans elders in a manner consistent with their gender identity or expression

Train all care staff in trans related issues so that they are culturally competent

Modify probate laws so that unmarried partners may leave estates to each other in the same way that married partners can accept estates/inheritances without going through probate

Ban transition and gender identity or expression as a single justification for an elder to lose legal competency to handle their own affairs

Train elder care counselors who are tasked with identifying elder abuse in trans issues so that they are culturally competent

Train court advocates for the elderly in trans issues so that they are culturally competent

Support day programs and other elder care initiatives that include trans elders’ needs as part of their curricula

Support funeral services to comport with the gender identity or expression of the deceased, including their obituary, service, wake, and directed donation campaigns

Tomorrow I’ll list what I and others see as the needs of trans people who are in specific circumstances and who may be even more vulnerable because of those circumstances. Again, these are needs that I don’t see taken up by HRC even in its latest round of “we care, we really care” communication. And please, feel free to add to my lists if I have left anything out. Because of course I have.

August 29, 2014

Questions Answered About My Writing

Cooper Lee Bombardier tagged me in some author chain mail thing, and normally I’d avoid a meme but first, he’s a really nice fella, and second, it’s about writing, so heck, I could bloviate about that all day. Here are my answers to four questions he posed:

1) What are you working on?

I’ve got several projects right now; in all honestly, probably too many. But here they are—a novel about four different gender non-conforming people from different eras in the United States, who by chance come together to build a high school for queer and trans youth. I’m trying to look at LGBT generationality, invisible history, the fracture lines across our communities, as well as more general themes of redemption, struggle, the fallibility of memory, and what indebtedness we have to each other.

I’m also in the middle of revisions to my followup memoir, Bumbling into Baby, which as it sounds, is about Susanne and my attempts to start a family. It’s told in the same tone as Bumbling into Body Hair, so it’s a humorous story, even as it makes some criticisms of the medical system, reproductive politics, and ideas about family.

And then I’m working on a non-genre short story about a trans man with Alzheimer’s who forgets he’s trans. This is a story I’ve wanted to work on for a long time, and I’m writing it in reverse chronology (apologies to Chip Delany, who loathes structures like this). I’m not sure which market will work for it, but right now I’m just focused on the story and the writing.

2) How do you think your work differs from others in its genre?

Transgender memoirs have a bad reputation, and much of that is deserved. There were a lot of books (well, at least a dozen or so) that came out a decade or more ago, and that were rather prescriptive in the messages and themes they espoused, like trans people are only this way or that, think this thing or that, and so on, which means they’re caught up in the whole unhelpful question of what makes trans people “authentic” or not. I intentionally pushed against that narrative to set up the story in a specific place and time and tried to highlight the message that worrying about authenticity is a red herring and a distraction. As for my science fiction and young adult work, I don’t see a lot of books (or okay, any) that investigate gender identity, sexual orientation, and queer/trans history the way that I do. It’s great to see so many wonderful stories about coming out, first relationships, and the decision to transition; I absolutely think young readers need exposure to these narratives. But I’m more interested in giving young adults some new ideas about what life could look like three, ten, thirty steps after all of the initial process. So that’s how I think my work is different.

3) Why do you write what you do?

I suppose I already just mapped that out a little. I’m interested in making more visible the largely undocumented history of queer and trans people in North America. It may not be possible to relay the “real” history of AIDS or Stonewall’s riot, but we don’t need to consider that what the media’s told us is true is correct, either. I want to see my work engage those real-world events, ask questions about how we interpret our shared experience, and how that affects our present understanding and our commitment to each other going forward. I want to offer counter-narratives to the impoverished narratives of stories like How to Survive a Plague, which whitewashed the early ACT UP movement, and Dallas Buyers’ Club, which took the narrative away from the people who actually started a medication group in San Francisco. I think science fiction offers a huge opportunity to pull our reality out to its potential extensions and help readers ask about where we’re headed and where they want to be. And on a basic level, I want my readers to find themselves in my stories, especially if they don’t see themselves anywhere else in popular culture.

4) How does your writing process work?

It works however it has to for me to produce words. I fight against having a restrictive work environment, because I never know when I’m going to have the availability to write, what with two small children and their sleeping schedules and energy/attention needs being what they are. I keep it simple: laptop, notebook and pen, coffee drink or fizzy water, music I like. I do a lot of writing in coffee houses but I also can write at the dining room table if need be. Because I can’t often luxuriate in large windows of time for writing, I have trained myself to get right back into a story, like sky diving, and now I only need 3-5 minutes to check email, Facebook, Twitter, etc., before I’m into the document and the universe I’ve created. It wasn’t easy to pare it down from 45 minutes of screwing around, but I got there!

In general my process starts with a lot of thinking, letting my mind wander over the characters and the story idea. Picture an elephant picking up a rock with its trunk and manipulating the rock, turning it over and around and sensing if its gritty or smooth or jagged or what. I think about my characters’ back story and motivation and whether they know how to play the guitar, for instance. Then I start to write the back story, with no intention of it landing in the main story itself. (But sometimes a little of it does.) Then I go on to write the first draft and I don’t stop to edit or revise, I just work on getting it done. If I decide to change a character mid-stream, I go ahead and give myself permission, and keep writing. Nothing stops the laying down of words in the first draft. It’s going to be horrible writing in any case, but I’ll clean it up later. When I’m done with the first draft I give myself a little break and go into revisions, and those can number in the teens for me. Every revision looks at something different—did I get the tone right? how’s the dialogue? is the character work believable? does the main story hold up?—and then I am ready to copy edit and get beta readers for outside feedback.

Well, those are my questions, and my answers. Authors, if you’d like to be tagged to go next, let me know!

August 27, 2014

Sounds I Miss

I took one of those online hearing tests last night, the kind that test the upper Hz frequencies that only the young people can hear. I dropped out after 12,000Hz and tried not to be depressed by my 44-year-old inner ears. Middle age is here in my life, even if it doesn’t come in the form of a Gregorian Chant. (Although maybe it should.) In all fairness, it’s not really much of a loss, that 12,005Hz and higher range. I don’t need to hear squeaky buzzing, right? (Maybe, if Emile and Lucas decide to use them as ring tones on their someday cell phones.)

I took one of those online hearing tests last night, the kind that test the upper Hz frequencies that only the young people can hear. I dropped out after 12,000Hz and tried not to be depressed by my 44-year-old inner ears. Middle age is here in my life, even if it doesn’t come in the form of a Gregorian Chant. (Although maybe it should.) In all fairness, it’s not really much of a loss, that 12,005Hz and higher range. I don’t need to hear squeaky buzzing, right? (Maybe, if Emile and Lucas decide to use them as ring tones on their someday cell phones.)

But there are some sounds I haven’t heard in a while due to lack of proximity, circumstance, or attrition. Here are a few of them:

Ocean foam—I didn’t make it to either the Atlantic or Pacific Ocean this summer, so I haven’t been listening to waves. But more than the sound of furious crashing surf, I love the sound at the very end of the wave, when the bubbles aerated into the ocean water explode and leave the liquid, making a quiet hiss before the tide is drawn back into the sea. It’s a sound that requires one be right on the shoreline, that one be quiet, too, because any sound smothers the foam hiss. I can hear a glimpse of it if I put my ear next to a stream of seltzer water running over ice; there’s that same bubbling up and collapse. It’s like a sigh from water, and when I can listen to it and see the horizon of the ocean in front of me, I feel at peace.

Quiet cat footfalls—I love hearing Emile trotting down the stairs or along the hallway on the main floor of our house. It’s often closely followed by a question, a calling of “Mommy” or “Daddy,” or a declaration like, “My belly is hungry.” These sounds are terrific and often amusing. But I also adore less assertive steps, like my sweet first cat Willie used to produce when I’d come home from school. It was a thump as he jumped off the couch in the family room and a dot-dot-dot-dot as he’d bounce over to me, and by the end of his jaunt he would have assumed an air of nonchalance, as if we both didn’t already know that he was totally excited to get a pet and a scratch behind the ears.

Drip coffeemakers—Truth be told I don’t drink much coffee anymore, not like I drink espresso. I haven’t own a drop coffeemaker in going on twenty years. Nowadays I use a French press, which requires only a little patience and a careful amount of pressure to ease the filter to the bottom of the cup. I miss ye olde Mr. Coffee drip coffeemakers, with their sudden guttural cry when the water in the reservoir would run out into the pot. It was like an alarm without being an alarm, an audible signal of doneness that needed no extra mechanization. I admit it; I’m addicted to my lattes, and I enjoy the velvet mouthfeel of French press, but the 80s are alive and well in the drip coffeemaker.

Telephone bells—After drip coffee, you knew this one was coming. It harkens back to the 20th Century, of course, but it is nice to me that phone calls used to be such a clear sound all their own. My iPhone 5S sounds like a pin dropping—WTF kind of ring tone is that? And see that? Ring TONES? This was a bell. It was easily differentiated from say, a fire alarm bell, a class bell, the Liberty Bell, etc. They were loud as anything. I could hear the phone ringing in my room upstairs in the house I grew up in from the back yard (and of course I could burst through the house and get to it before anyone hung up, because that phone could ring forever, unattached as it was to an answering machine). If I decided to wait up for a phone call I considered it a win if I could lift the receiver before the hammer could really ring the bell, and even if it gave away to the person on the other line that I was strangely desperate to hear from them.

Eastern seaboard birds—I listened to the birds as I sat in our back yard this summer, and while they were nice, I still hear bird calls in my head that aren’t reaching my ears anymore. Like the Oriole, the Eastern bluebird, and the Mourning dove (even though they’re supposedly in Walla Walla’s region). There must be some unconscious connection to my childhood memory, but I consistently note the absences of familiar bird sounds, even if I am stunned to see so many hawks, eagles, and falcons in the skies here in southeast Washington State.

What are your favorite sounds you haven’t heard in a while? Did you have to think about it, or do you actively miss a particular sound?

August 22, 2014

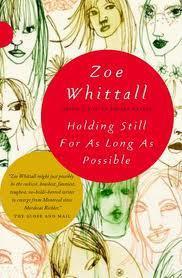

“That’s My Secret. Holding Still”: A Review of Zoe Whittall’s Novel Holding Still For As Long As Possible

Nice review, principled criticism.

Originally posted on Casey the Canadian Lesbrarian:

Originally posted on Casey the Canadian Lesbrarian:

Reading Zoe Whittall’s Toronto-set novel Holding Still For As Long As Possible is kind of like reading a wittier, more exciting version of my urban early-to-mid-twenties queer life in the 2000s. It was fun and nostalgic for me to jump back into this world, but it is uncanny to read a book featuring characters that are so much like you and the communities you’ve known. I mean, in a good and a bad way: these are white, bike-riding, middle-class background, artsy, educated, FAAB queers. Unfortunately, both people of colour and trans women are pretty absent from the world of the book, although this is something that was mostly true in my experiences in similar communities in Halifax, Victoria, and London in that stage of my life.

Reading Zoe Whittall’s Toronto-set novel Holding Still For As Long As Possible is kind of like reading a wittier, more exciting version of my urban early-to-mid-twenties queer life in the 2000s. It was fun and nostalgic for me to jump back into this world, but it is uncanny to read a book featuring characters that are so much like you and the communities you’ve known. I mean, in a good and a bad way: these are white, bike-riding, middle-class background, artsy, educated, FAAB queers. Unfortunately, both people of colour and trans women are pretty absent from the world of the book, although this is something that was mostly true in my experiences in similar communities in Halifax, Victoria, and London in that stage of my life.

What I’m saying is that what Whittall is doing in this book is limited, but she’s doing it really, really well. Like, I can’t…

View original 1,056 more words

August 15, 2014

Fear Weary

(This is republished from my Medium.com account, with citations added in this version.)

(This is republished from my Medium.com account, with citations added in this version.)

In 1983, I was 13 when Halloween rolled around, and instead of worrying about the exact placement of my zombie blood on my face, I was listening to my parents talk about the Tylenol tampering cases, and how I needed to inspect my candy wrappers before I ate any of it. It was a lot of discipline for a young teenager, but the message came at such a high frequency of fear that I heeded their proscription.

In 1982, the cover of our Time Magazine subscription screamed about herpes and how many people were walking around with such a horrible, dirty virus. By 1985 the virus emergency had shifted to HIV, replete with all of the horrifying ways in which it possibly traveled to other people. (Mosquitos! Swimming pools! Soft drinks!)

The mid-to-late 1980s had us fearing crack cocaine,* the last throes of the Soviet Union, and what would happen if we elected Gov. Dukakis instead of Vice President Bush. Not a year has gone by that I can remember in my lifetime in which we didn’t have some huge bogeyman to fear as presented in the US media.

PCP. PCBs. Iraq (the first time), and then soon after, Desert Storm Illness. Terrorists, welfare recipients, inner city youth, trade unionists were all out to get us. We couldn’t even celebrate the new millennium without fearing that all of our computers were about to implode with bad programming.

Then September 11, 2001 happened, and the fear messaging finally had corporeal form. The few images that made it over the Internet were horrible beyond description. The fear machine went into overdrive, and some of heard news reports that the Sears Tower was down in Chicago, the White House had been attacked, there was fire in Los Angeles, none of which turned out to be true.

The panic among the Bush Administration staff was palpable, at least in DC. Old-time bureacrats that I knew where astonished at how fearful George, and Donald, and Dick were when the risks from al Qaeda had been so well documented. People in the Federal service whispered to each other that it seemed like the White House was scrambling to invent new policy out of simple fear and with no rational basis. From this stance Bush pushed through the creation of the Department of Homeland Security with its most public face, the Transportation Security Administration. I was on the team to create TSA’s first web site. It was clear to me in those meetings that they were making it up as they went along. For one thing they’d spent big bucks on a content management system for the web site, but used an untrained staffer to put it together and so every piece of content was in one enormous file.

I drove through the checkpoints set up by the Capitol Police, stopping and rolling down my window every time I got near to the US Capitol, which felt weird and made me more aware of my half-Arab background than I’d ever noticed before. (Maybe it was all the “Arabs Go Home” signs tacked up near my office in Bethesda.) Fear had somehow become a part of my routine, either in terms of me mediating someone else’s fear or processing my own fear.

Appropriations were shifted across the Federal budget to shore up homeland security, and thus began the huge shipments of military weaponry that we’re talking about this week with regard to the events in Ferguson, Missouri. The very idea that a town of 21,000 needs a SWAT team or a tank is absurd to many of us. But somehow we’d come to believe that every town in America needed these things, just in case. There could be another Columbine, or Boston Marathon bombing. Fear intersected with political will not to create gun control restrictions, not to provide for drug user health and recovery, not to help lift people out of poverty or support their mental health needs, but to hand grenade stockpiles to ordinary police officers who in the normal course of duty should have no need for grenades.

Certainly the epidemic of shooting, profiling, and beating up young Black men is complicated and goes well beyond the question of fear-mongering and manufacture in the United States. Still I can’t but wonder: if we weren’t so indebted to feeling fear, would Michael Brown have been able to walk in the street without losing his life?

There must a come a point when fear does not motivate us into hate and violence anymore; when we are spent, or weary, or suspicious that this approach has changed our nation too much. When the list of people to fear (terrorists, teachers, immigrants, leftists, artists, climate change scientists, lesbians, transsexuals, women…) is so large that there is scarcely anyone left not to fear, and that when we turn to face these remaining people to see they too are holding rifles with white-turned knuckles, that we must simply give up on fear and try something else. If fear has isolated us from each other, perhaps someday soon we can give community and communal good a go as our national motivation instead of fear.

* Reinarman, C. and Levine, H., The Crack Attack: Politics and Media in America’s Latest Drug Scare. In J. Best (Ed.). Images of Issues: Typifying Contemporary Social Problems. New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1989; see also Reeves, J. L. and Campbell, R., Cracked Coverage: Television News, the Anti-Cocaine Crusade, and the Reagan Legacy, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1994.

August 8, 2014

Excerpt from Short Story, Heart of Silence

Just a bit of what I’m working on this month:

Reginald runs down the hallway, his sneakers squeaking on the tired linoleum. It’s Joe in B14 again. Alzheimer’s dementia, sometimes gets combative. Reginald is the only orderly on this shift who knows how to calm Joey down. He wouldn’t have to beat a trail to the door so often if the fucking doctor would get this guy the medicine he needs, but hey, ole Reg is here to take care of things.

Reginald runs down the hallway, his sneakers squeaking on the tired linoleum. It’s Joe in B14 again. Alzheimer’s dementia, sometimes gets combative. Reginald is the only orderly on this shift who knows how to calm Joey down. He wouldn’t have to beat a trail to the door so often if the fucking doctor would get this guy the medicine he needs, but hey, ole Reg is here to take care of things.

He bursts into the room. Lime green walls, plastered with random bits of newspaper articles because Joe insists that’s how people stay on top of current events. Someone pays for Joe’s private room because his insurance certainly doesn’t include that, but nobody knows who this sugar momma or daddy is. And why don’t they ever come visit?

Joe is screaming at the mirror in his bathroom. It’s full of streaks and a lot of the silver on the back side of the glass is missing so it doesn’t even but half-reflect a person anymore. But Joe is a stubborn bastard, so when Reginald runs in he finds Joe leaning on the sink, staring at himself and screaming.

“This mirror is broken,” he says.

“Come over here, Jocelyn. It’s okay.”

“What evil did you put in this mirror? Why are you doing this to me?”

“It’s okay, you’re okay,” says Reginald.

“There’s someone in the mirror!”

“Let’s come over to the other room,” says Reginald, gesturing for Joe to come with him, as if making a small current of air with his arms would draw the old man in.

“Tell me why there’s a strange man in my mirror!”

Reginald can’t tell him why.

“I’ll talk to the building manager. We’ll get the mirror out of your bathroom.”

That seems to settle him a little. It always does.

“Okay. Yes. I want it gone. I want that mirror gone!”

One of the small blessings of Alzheimer’s—the tricks others learn to calm the patient usually work again and again. At least until their cognitive capacity takes another slide down into oblivion.

“Sure, I’ll call the building manager. We’ll make it go away.”

There is no building manager, no approval to remove the mirror in a nursing home that has a high turnover rate of patients. And no way to explain any of this. Reginald has done what he can to fuck the mirror up so much that Joey can’t use it anymore, but yeah, he’s like an old mule.

“Let’s see if Judge Joe Brown is on,” Reginald says, his large arms finally making contact around Joe’s shoulders, guiding him gently to the easy chair next to the bed. The flat screen television is the only new thing in this room, so it is locked to the wall.

“Come on, Jocelyn.”

The name gets Joe to settle down a little more.

Because Joe has forgotten, in the twisted ruins of his memory, that he transitioned forty years ago and is no longer the woman he expects to see in a mirror.

August 3, 2014

Quick Stop to DC, or How I Learned to Anticipate Gentrification

I just jumped into DC this weekend after an absence of a few years, taking a quick flight from Detroit while we’re still on vacation to attend an LGBTQ book festival on U Street. It’s been truly fantastic to see old friends and have the kinds of sincere conversations that are hard to find with people one meets in one’s forties instead of in one’s more vulnerable youth. I suppose we erect sturdy fortresses in the interim, but I’m not sure why or if that’s helpful for us.

I just jumped into DC this weekend after an absence of a few years, taking a quick flight from Detroit while we’re still on vacation to attend an LGBTQ book festival on U Street. It’s been truly fantastic to see old friends and have the kinds of sincere conversations that are hard to find with people one meets in one’s forties instead of in one’s more vulnerable youth. I suppose we erect sturdy fortresses in the interim, but I’m not sure why or if that’s helpful for us.

The OutWrite festival was successful, and here it is only in its fourth year. It would have been nice to know before I left Walla Walla that I’d be responsible for bringing my own books to sell, because then I’d have had more than my reader’s copy with me. (Crossing fingers the Internet pulls through for me and people shop online to get them.) I was grateful to see so many familiar faces, people I’ve known from when I lived in the District and did earlier activism there, and get to meet some new folks who are doing interesting work in LGBT literature.

But U Street was almost unrecognizable to me. I encountered disorientation on every block, until some anchor in my memory would pipe up—There’s Ben’s Chili Bowl! There’s the Black Cat! That’s Dukem Ethiopian restaurant!—but for the most part the very cityline had shifted. Where once a sad used car lot hugged the curb on 14th Street between S and T, now there was a thriving oversized restaurant, Ted’s Bulletin, complete with 1940s and 50s throwback references that were not part of the neighborhood here in that time. What a wonderful white DC it was, beamed the business, with its homemade PopTarts and milkshakes served with the extra in the blender can. Was it?

Loft apartments had sprung up like bishop’s weed all along 14th, which had once been a warehouse district, and then a holdout for artist’s studios and a well known homeless shelter. The shelter had sold its property for several million dollars when I sill lived in DC, so nobody was surprised when the corridor turned over in that gentrifying way. But nothing could prepare me for the Trader Joes, its parking garage carefully guarded by a tall man in a uniform. Given that I now live 200 miles from the nearest Trader Joes store, I had some level of internal turmoil over this discovery on the street—should I run in screaming and grabbing the schoolhouse cookies and pork potstickers, or should I stand slack-jawed in horror at what has become of a city that was once 75 percent African American, and then 54 percent, and still falling?

Whatever happened to White Flight, and when did the Trader Joes executives decide they should make a foray into DC? I can still remember the headlines in The Washington Post about how few grocery stores remained in the city. Grocery stores. Simple places with small selections, curled around the corner of a block, catering to blue collar workers? Now the District boasts a Harris Teeter, a Trader Joes, its own Target. Instead of chitlins and pig feet folks can buy prettier processed food that speaks neither to any particular culinary heritage nor to the realities of living in a slowly recovering economy.

I was happy to see my old mates who are near the city but who don’t come into its confines all that often anymore. Many of our old haunts are gone, or have changed what and who they serve, and battling the traffic makes less sense to them. More than ever the traffic lights are a hair-trigger away from issuing a costly violation, the parking spots are as hard to find as ever, and the streets seem more crowded. I may sometimes slink into sullen thoughts about living in Walla Walla, but what’s now clear to me is that there’s no going back, either.

July 18, 2014

The Hornet Hunter

Anyone who has spent more than five minutes with me in the spring or summer knows that I am no fan of insects. Maybe bees and dragonflies get a pass, and ladybugs. (But not those ladybug knockoffs.) But beetles, spiders, roaches, silverfish, millepedes, ants, I don’t want them on me or even near me, as impossible as I know that is. We’re very outnumbered by the insect world, and I super don’t enjoy thinking about that reality.

But there is a special level of ugh I hold for stinging insects like wasps and hornets and yellowjackets. I can deal with the fact that honey bees and bumble bees sting because heck, they need some kind of defense for themselves and they only use them as a last resort before dying. But those OTHER stinging insects are like extremist NRA members wearing their Glocks on their hips for a trip to Walmart, ready to shoot anyone around them and then keep on shopping like it’s no biggie. So when I see not one, but two hornets’ nests under construction on my newly acquired car port (otherwise known as the place where I park the family car four times a day), I have to take action. Especially when said construction includes laying the foundation for the next generation of venomous bugs.

A neighbor suggested I go to the hardware store at the eastern edge of Walla Walla, which turned out to be a ranch and home supply store. Here I could get a feed bag for my horse, any kind of Carhart gear my heart desired, or fake eggs to dupe the hens in my coop to lay more eggs. Or a can of thick poison guaranteed to kill on contact. I explained that I had a bee sting allergy thing and that I wanted to make sure the hornets would never get near me once I bamboozled them with my noxious elixir. The small man, his Vietnam Veteran ball cap pulled low over his forehead, squinted at me.

“Oh, they’ll die as long as you hit ‘em,” he said. I felt judged. I can aim a can of poison, mister, I thought. He told me it should work up to twenty feet away.

I thanked him, considering whether I should refute his expectations of my hardiness and marksmanship, and then wandered away to the corner to pretend I had an enormous stallion in my backyard named Killer. (I have actually ridden a horse named Killer, but that’s another story.)

At this point I should mention that Walla Walla was in the midst of a heat wave, which it gets every summer in July or August, the temperatures of which typically reach into the three digits, just enough to remind all of us that even if some team of people planted elms and maples and poplars and birch here one hundred years ago, we live in the middle of a desert. It’s dry heat, yes, but 104 is scalding no matter the humidity percentage in the air. Our air conditioner ran constantly, and little Emile’s room, up on the second floor in what used to be the attic, had an extra portable AC unit just to keep it in the mid-70s. My office, also on the second floor, is probably unusable until September 30th.

I read up on hornets and learned that they “go dormant” at dusk, which at our latitude for this time of year means about 9:45. This was fine because presumably both boys would be asleep at that point so I could murder god’s creatures without explanation to them of either my skittishness or motivation. I put on thick cargo pants, ankle-high hiking boots (good for stamping out bugs should it come to that), a long-sleeved sweatshirt, a baseball cap, and a long wool scarf that I wrapped around my neck and bottom half of my face. I walked through the living room on the way to the back door and heard Susanne guffaw. Nobody respects my bravery!

She came out with me, through the back gate to the carport, and I realized I’d waited too long after sunset, because no matter how I squinted I couldn’t see either hive. Was it over here, or seven inches to the left? I didn’t want to miss, and I didn’t want to spray at the wood wildly, because that’s what amateur hornet killers do and OMG THEY STING PEOPLE FOR CRIPES SAKE.

Susanne was willing to stand a good fifteen feet behind me and shine her iPhone flashlight onto the top of the carport. The poor soul only had on a short sleeved shirt and thin summer pants. Of course, she wasn’t sweating like a stuck pig, either, but there I was with streams of perspiration gushing down my temples and fogging up my glasses. I breathed through the scarf, sounding in my own ears like Darth Vader. I pressed the trigger and realized that in fact, I was attempting to destroy flying stinging beings with what amounted to toxic silly string. A thin white stream of poison shot out from the canister and made a splashing sound on the nest, and the four hornets dropped to the ground, dead.

Whew.

Next I moved on to the smaller nest—I’d wanted to take out the bigger challengers first because like, strategy and stuff—and Susanne gave me light again. Again the milky substance crashed against the hive, but this time a hornet broke off and started buzzing in the air. Had I missed? Was it somehow immune to death?

It mattered not.

“Go, go go!” I yelled to Susanne, who ran through the gate like a jackrabbit. I ran down the alley behind our house to the street. Surely I could outrun a hornet! In my mind I saw myself jumping into a jake for safety. I had practiced just such a maneuver when I was a child, and had trained myself to the point of being able to hold my breath for one hundred and twenty-five seconds. The nearest lake to us was a twelve-minute drive away.

“I’ll meet you around the front!” I said, gripping the poison in my right hand like a football. In 99-degree heat I bolted down the sidewalk, around the corner, and up the concrete steps to our front door, the scarf trailing behind me like a really crappy cape, sweat stinging my eyes, and my feet feeling overheated and heavy.

Inside, I yanked off the hat, scarf, and sweatshirt in one wave of my hand.

“Did you get stung?” asked Susanne.

“No.”

“Good.”

“I got the nest.”

“Good.”

I walked into the kitchen, took off my boots, and put the poison back in the plastic bag from the store.

The next morning, I ran into my neighbor Denny, who lives on the other side of the alley.

“I bundled up last night and sprayed those hornets’s nests,” I said.

“Bundled up?”

I explained my outfit.

“Good for you, killing six hornets,” he said, and he patted me on the back.

No respect, no respect.

July 7, 2014

Misinterpretation vs. Post Liberal Disingenuousness

Everyone is finally talking about J. Jack Halberstam, but it’s not because he broke out the coup of academese or wrote a readable deconstruction of language, politics, and identity. Instead, Halberstam waded into the very tired “tranny” debate, and along the way, managed to become the next Dan Savage, Tosh.0, Seth MacFarland of the LGBT universe. Like a ball of sticky goo (sticky goo being oh so funny, don’t you know), he picked up along the way a raging misreading of lesbian political history, a misunderstanding of stated boundaries, a misappropriation of assault survivor’s lexicon, and a misarticulation of gender performance.

Halberstam, in his piece, basically starts off bemoaning how nobody understands (the Spanish Inquisition) Monty Python anymore, and then delves right into his own lesbian angsty memory:

I remember coming out in the 1970s and 1980s into a world of cultural feminism and lesbian separatism. Hardly an event would go by back then without someone feeling violated, hurt, traumatized by someone’s poorly phrased question, another person’s bad word choice or even just the hint of perfume in the room. People with various kinds of fatigue, easily activated allergies, poorly managed trauma were constantly holding up proceedings to shout in loud voices about how bad they felt because someone had said, smoked, or sprayed something near them that had fouled up their breathing room. Others made adjustments, curbed their use of deodorant, tried to avoid patriarchal language, thought before they spoke, held each other, cried, moped, and ultimately disintegrated into a messy, unappealing morass of weepy, hypo-allergic, psychosomatic, anti-sex, anti-fun, anti-porn, pro-drama, pro-processing post-political subjects.

Here are my issues with this paragraph:

I would expect an academic to understand his or her own experience in a political movement as exactly that, one data point. One experience. Extrapolating from one data point? Not an intellectual engagement.

This completely misses the point that in the 1970s and 1980s (and 1990s, let’s get real) lesbians who came together to build a new community often did so under duress, sans love of family, against a culture that was much more weaponized against them than we see in 2014. There were a lot of things to cry about, a lot of broken people trying to make their way through the world with few resources. A lot of women lost their jobs expressly for being gay, and they had no recourse. The closet was a different beast. AIDS was claiming lives and lesbians were often on the front lines. So some of them finally felt that with their energy and input they were creating a space from which they could speak up about their needs (colognes do actually cause allergies), fighting one’s parents and siblings does leave one fatigued, but thanks, Dr. Halberstam, for asserting that these people who thought they were your comrades were messy and unappealing.

This is really ableist. Though according to Halberstam’s critique there’s no room to claim that ableism is bad. I’m just a bad neo-liberal, right?

Camille Paglia better look out because Halberstam’s paragraph reads like it was stolen out of her next manuscript.

Halberstam’s next paragraph pulls out two threads in the 1990s:

Political times change and as the 1980s gave way to the 1990s, as weepy white lady feminism gave way to reveal a multi-racial, poststructuralist, intersectional feminism of much longer provenance, people began to laugh, loosened up, people got over themselves and began to talk and recognize that the enemy was not among us but embedded within new, rapacious economic systems. Needless to say, for women of color feminisms, the stakes have always been higher and identity politics always have played out differently. But, in the 1990s, books on neoliberalism, postmodernism, gender performativity and racial capital turned the focus away from the wounded self and we found our enemies and, as we spoke out and observed that neoliberal forms of capitalism were covering over economic exploitation with language of freedom and liberation, it seemed as if we had given up wounded selves for new formulations of multitudes, collectivities, collaborations, and projects less centered upon individuals and their woes. Of course, I am flattening out all kinds of historical and cultural variations within multiple histories of feminism, queerness and social movements. But I am willing to do so in order to make a point here about the re-emergence of a rhetoric of harm and trauma that casts all social difference in terms of hurt feelings and that divides up politically allied subjects into hierarchies of woundedness.

Look, is there a limit to liberal feminism? Yes. Was it too easily fraught with the kind of “Lean In” thinking that furthers capitalism on the backs of more marginalized (read: of color) women? Absolutely. But why is it framed in terms of humor? You know who talks about women who need to “loosen up?” Sexist men, that’s who. “Loosen up,” the very phrase has been used since at least the last mid-century to dismiss women’s needs and boundaries. It doesn’t shock me in the slightest that Halberstam uses it here because he’s making the very same move. Your right to a perfume-free environment is bunk. Your claim that you are hurt is bogus. Loosen up and you’ll see that things won’t bother you as much. This is as clearly an anti-intellectual engagement around women’s boundaries as one can make.

Should we examine institutions for their role in perpetuating oppression differentially across race, class, gender, and other intersections of power? Yes! But can we take a step back and remember that we all have a lived experience inside of these institutions and forces and that people are situated in different places in culture? Sometimes their situatedness means that they experience a lot of pain and understand that pain as emotionally exhausting. Sometimes they find themselves the survivors of violence and those moments radicalize them such that they begin to make new inquiries into the world around them. Locating ourselves within this postcolonial/neocolonial world is an honest means of making revolutionary critique, it does not take away from it. And if we are lucky enough to have escaped “harm and trauma” then a critique with integrity would identify that as a site of privilege. Which means that when Halberstam is calling a “rhetoric of harm and trauma” problematic in that it is divisive, Halberstam is bing a privileged individual telling those with a different history that they need to be silent.

It is in this way that I read Halberstam’s piece as silencing, as not in solidarity with people who have made requests of us, the other people on the broad Left who have said at one point or another that we are all in this together. And when I get to that interpretation of Halberstam, the rest of his piece makes sense, in an internal consistency sort of way. It is actually antithetical to an emancipatory politic. Here is why.

Much of the recent discourse of offense and harm has focused on language, slang and naming. For example, controversies erupted in the last few months over the name of a longstanding nightclub in San Francisco: “Trannyshack,” and arguments ensued about whether the word “tranny” should ever be used. These debates led some people to distraction, and legendary queer performer, Justin Vivian Bond, posted an open letter on her Facebook page telling readers and fans in no uncertain terms that she is “angered by this trifling bullshit.” Bond reminded readers that many people are “delighted to be trannies” and not delighted to be shamed into silence by the “word police.” Bond and others have also referred to the queer custom of re-appropriating terms of abuse and turning them into affectionate terms of endearment. When we obliterate terms like “tranny” in the quest for respectability and assimilation, we actually feed back into the very ideologies that produce the homo and trans phobia in the first place!

It’s not surprising that Halberstam glosses over what “these debates” are about—because he misses their point entirely. The history here is that some trans women, most of them under 30 and representing a younger generation of trans women, have said for at least the last decade, that they want everyone in the LGBT umbrella (because we’re a political coalition, at least in the eyes of the Family Research Council), to stop using the word “tranny.” For them, they’ve stated plainly, the word has been used against them during violent attacks, during personal attacks, in the act of refusing trans women housing, employment, and education. It’s been deployed to alienate them, disempower them, and yes, kill them. To not even bring to light WHY trans women have asked us to stop using the term is to once again dismiss the request. I’ve heard all sorts of defenses for continued use of the T-word, from loyalty, a sense of nostalgia (usually among gay men), a pseudo-academic argument for free speech (which even SCOTUS understands as different from hate speech), and some misguided sense of entitlement (you can’t tell me what to say!). But I’ve never seen anyone make the case, until Bond’s and Halberstam’s essays, that getting rid of the word would perpetuate transphobia.

And that idea, frankly, is preposterous. It would mean that mainstream (read: non-LGBT) individuals would come across the word and think, wow, I love transgender people. Look how cool Justin Vivian Bond is! Check out that Ru Paul! If they say it, I can say it, and it will mean I love trans women everywhere. It would mean that in the greater context of people bashing trans women and using the very same word that it’s the moment of drag frivolity (or what Halberstam would say is humor) that would transcend as the stronger signified, such that what, eventually if we just scream “tranny” often enough nobody will think of using it against trans women anymore?

No. I say no. Not only is this implausible, it means withholding material reality that trans women of color are the single most abused group in the FBI’s hate crime statistics. It would mean making invisible serious, authentic requests that women have made in order to keep a fucking word in the community. It would mean that there is no linkage between an epithet and a bigoted attitude toward a group. It means nothing less than the justification, rhetorically, of demeaning trans women in a larger community that has already demoted their political, social, sexual, and economic needs and that still will call up a sister and ask her to sit on the Pride planning committee so it can have a token trans woman in the room. It is nothing more than the lazy, anti-intellectual side-talking history that has worked against real change for LGBT people since we came together as a community during the Stonewall riots. During which transgender people and gay men fought side by side, by the way.

Saying that requests not to use a pejorative term or to put a “trigger warning” on a text of some kind are the kind of neo-liberal mushy (sorry, “messy, disintegrating”) inquiries that are limiting the movement is to erase the reality that for many people under the LGBT umbrella, we are broken and hurting and looking for support. Is it funny and humorous? No. Should a political movement use humor as one of its methods for liberation of its people? Sure, but Halberstam is making fun of ourselves, and the target ought to be those systems of oppression Halberstam says we should be focusing on.

All Halberstam’s piece does is give more life to a debate that is taking time and energy away from the real work we need to do. If a sexual assault survivor asks to be told up front if the content she’s about to see is violent, it is no skin off of Halberstam’s nose to tell her. Just as it is no loss to let the T-word fall to the way side, the way we have let many, many other words do in the last forty years. That Halberstam would pen this piece and offer nothing else for trans women in coalition with LGB interests, political, artistic, or other, tells me that he’s not really interested in trans women’s interests. And that is the sign of a disingenuous argument.

Of course we have made strides in the last two generations. That’s the point! It’s not the fault of younger trans people that they have come into a world that has the slightest grasp of what transgender identity is or can be. And even if an individual trans youth comes into a slightly more understanding culture, it doesn’t mean they face a more supportive immediate climate. Forty percent of homeless youth are LGBT, according to a recent survey. An unimaginably high percentage of trans people have attempted suicide. Saying:

These younger folks, with their gay-straight alliances, their supportive parents and their new right to marry regularly issue calls for “safe space.”

is as disingenuous as it gets. Not only should we be proud that the culture in the rightward-moving US has gay-straight alliances in some areas, we should not use it to dismiss requests for safer space. I may agree that there is no such thing as a safe space, and I may agree that left-wing policing can be used against in-community people to their detriment, but the problem isn’t in the call for safe space, and it’s certainly not the case that we ought to curtail any space that is more supportive than in decades past. This is just nonsensical. And I don’t see, once again, a good argument made here around gentrification. (For that, turn to Samuel Delany and Sarah Schulman.)

Halberstam then makes a leap from trigger warnings and the T-word and safe space to this:

…as LGBT communities make “safety” into a top priority (and that during an era of militaristic investment in security regimes) and ground their quest for safety in competitive narratives about trauma, the fight against aggressive new forms of exploitation, global capitalism and corrupt political systems falls by the way side.

Actually, no. Some segments of the community have set boundaries around specific issues of sexual violence, violence, and individual terms, and some segments of the community have tried to open a dialogue about safety. Our safety is of paramount concern to our political agenda (the one that deals with institutions and stuff, remember). In the past week I’ve seen at least four articles about Black trans women murdered, missing, or attacked. If we can’t talk about safety being a top priority, we’re pretty safe, in all probability. If we can’t talk about intersectionality because we’re afraid someone will claim we’re starting an oppression Olympics, then we can’t talk for very long. And if we’re concerned about policing, then what the hell is Jack Halberstam doing in this piece? Because it reads like a ship ton of policing to me.

June 10, 2014

The Mortal Coil

For the first time in several years, I didn’t ponder my own mortality on my birthday. Well, I’m lying, in that I had a moment, late in the day, in which I wondered out loud if I’ve passed the midpoint of my life at age 44. Susanne is confident I’m still in the first half, but in any case, there was a small reminder that life is fleeting and best implemented with enthusiasm. To put it more precisely than I did in the first sentence of this post, I didn’t get all morose about aging and dying, which is good, because I don’t generally walk around spouting off nihilistic prophecy. Though some of my birthdays in the last decade have been a bit—ahem—neurotic.

Two days after my birthday, a good friend and also my past and Susanne’s current physical therapist brought a huge balloon and a strawberry-rhubarb pie to the house to wish me a bon anniversairie. She apologized profusely (so Susanne tells me; I wasn’t home at the time) for being tardy, but Tuesday had just been too hectic of a day and she couldn’t get to it, and she hoped it wasn’t too awful of her to be belated about the whole thing. Who would be a stickler for dates when pie is involved? Seriously.

Two days after my birthday, a good friend and also my past and Susanne’s current physical therapist brought a huge balloon and a strawberry-rhubarb pie to the house to wish me a bon anniversairie. She apologized profusely (so Susanne tells me; I wasn’t home at the time) for being tardy, but Tuesday had just been too hectic of a day and she couldn’t get to it, and she hoped it wasn’t too awful of her to be belated about the whole thing. Who would be a stickler for dates when pie is involved? Seriously.

Emile of course was gaga over the balloon, which was transparent except for the rainbow-colored HAPPY BIRTHDAY and a giant rainbow cupcake. He exclaimed that there was CAKE on the balloon, pointing at it more like a professional hunting dog and not so much in a “J’accuse!” way. He also wanted possession of the balloon. I was willing to go along with this until he insisted on bringing it outside and releasing it into the gorgeous blue late spring sky, and then I grappled with my 2-year-old to get it back in the house. It now hovers above our mantle, the silver ribbon cutting through the middle of our family portrait as the balloon gently jostles around. Emile seems to have made some kind of peace with just being able to look at daddy’s present.

Less issue was made by my eldest child over the sudden appearance of pie. A cake would have been obvious, but a store-bought pie sits in an unassuming tin pan, kind of like a quiche, and while Emile will eat quiche (real kids do), he’s not going to lose his calm manner over one, either. The pie rested gently in a glass covered cake dish, seeming off the radar of small children. Until Grandma’s visit and our lunch yesterday, after which we carved into the P-I-E. Now Emile knows that P-I-E means pie and that marks the fist thing I can’t spell to keep it from his NSA-issued hearing.

On Saturday we went to a birthday party for a friend’s daughter who had just turned three. It was a potluck of sorts with a buffet born of random cuisine and convenience—hummus, pesto, wafer cookies, sesame noodles, hot dogs. Fancy water (so I call it) in a pretty glass dispenser looked refreshing mingling as it was with sliced cucumbers and basil leaves. There was also a universe of toys for small people, including lacrosse sticks (sized down for toddlers), bouncing balls, foot-propelled cars, water balloons, and an inflatable pool, grandly occupying the middle of the front yard like a conversation piece at a curated show. Emile squealed and Susanne rushed home in the car to gather up his pool hat, swimsuit, and swim diaper. We knew there would be no keeping him out of the chilly water.

He’s a kid who notices anything larger than the size of an ant, so of course he was going to dwell on the pool. I pulled him into the house’s side yard and tried to entertain/distract him with one of those ball and velcro paddle things. Apparently these only work if one’s toddler has decent aim, produced on at least a semi-regular basis. Soon enough Susanne ventured back to us and had Emile changed in quick order. Here is where we were met, however, with a strange storm of intersections that culminated in an emergency:

Emile’s nonexistent experience with inflatable pools—he only knew the pool at the YMCA and some rigid pools in friends’ yards

Older kids in the pools with their longer legs modeled jumping in and out of the pool with ease, which he wanted to copy

Twenty parents all in close proximity gave the sense that everybody was completely safe—how could anything go wrong in front of all of us?

He’d kept clambering over the edge of the pool to follow a ball that well, that he insisted on launching into and out of the water. Susanne had earlier given him some reminders that this was not like other pools he’d been in recently, and he had nodded that he understood. Oh, that meddling Mommy, his expression told us.

In a flash as he was rushing back into the pool he lost his footing and then he was under the water. Maybe a quarter second passed and we looked at each other, his chocolate brown eyes staring at me through the surface of the water, his bright blue hat still clinging to his temples, his fingers splayed open in shock, like they were tentacles searching for any purchase. In the next quarter second, or so it felt, I calculated that he was in trouble. Later it occurred to me that I’d had training in this very situation as a lifeguard in the last 1980s—it’s not the thrashing, screaming person who is in distress or close to drowning, it’s the still person who can’t figure out how to get their head above water. I calculated the quickest way to him and even though I considered running around the pool to get to where he was, I threw out this option instantly and dove in like I was stealing home plate.

It was some kind of parabola arc that I made, plunging into the pool and popping up at the other end, missing the 4-year-old who was also in the water, and then my hands were around my son and I pushed him up out of the water. He was still wide eyed and completely surprised and I knew I needed to assess whether he could breathe, which was easily figured out by seeing if he could talk.

“Are you okay, buddy?”

“I scared.”

I blinked back tears, and put my lips on his chest and gave him a sloppy zurbert. The fart sound was the only noise at the party, as the adults and kids had all noticed that I’d jumped into the little kiddie pool.

Emile laughed. I blew air onto him again and he laughed louder. I held his sopping head to my chest and kissed him and told him I loved him and he was okay. Which I think he knew. Maybe I should thank all of those swim classes, I thought, for teaching him to hold his breath under water. And soon after that thought he went back to splashing in the pool. I held onto my jeans which now had something like 18 percent of the pool’s water sopped up in their fibers. A few folks gaped at me. One asked if I’d fallen in. Maybe I’d gotten ahold of too much sangria.

I pulled out my cell phone and the host took it and put it in a bowl of rice. Two days later it still won’t turn on.

Susanne looked at me and put her arms around me as she handed me Emile’s beach towel.

“If you wanted a new phone you could have just said so,” she said, kissing me on my cheek. “Good Daddy.”

After the birthday cake came out and our bellies were full—pesto! cheese! sesame noodles!—we drove home, me sitting on the towel. I asked Emile that night about the incident.

“Were you scared when you fell under the water?”

“Yes, but you came and got me.”

“I did get you. I love you, Emile.”

“I love you too, Daddy.”

Yes, I sure hope I’m not at my own halfway mark yet.