Mitchell Hagerstrom's Blog, page 4

November 25, 2013

The Birthing of Fictional Characters

This is Yasunari Kawabata’s mistress and perhaps a model for the hot-springs geisha in his novel Snow Country. But I cannot reconcile this lovely face and her quiet demeanor with the rather brash semi-prostitute in Snow Country. More likely the geisha’s friend, Yoko -- a less developed character in the book -- was based on his lovely mistress.

This photo reminds me of the doll in the tall glass case that graced the office where I first worked in Micronesia, a doll presented sometime in the 1950s to the local island government by the Mitsubishi Company. The tall glass case kept her dust-free, but her once bright kimono and the sprays of wisteria she carried were faded. She, too, was lovely-faced, much as Kawabata’s mistress, and so unlike the modern versions of Japanese dolls I see when I google.

No doubt this doll was my original Mieko. My visual model, that is. Fictional characters do not spring out of mid-air. Fictional characters are a little of this and a little of that, a bit of this real person and a bit of that one, even a bit of someone else’s fictional character. In the case of Meiko, she’s more than a bit of myself -- hard to avoid when employing a first person narrative -- but she is also a bit of the Snow Country geisha, a bit of the refined 10th century court ladies in Murasaki’s Tale of Genji, and perhaps more than a bit of my own East Texas grandmother.

After leaving the Federated States of Micronesia, I moved briefly to Guam and then to Washington, DC, and from there to San Francisco where I took a position with a venerable steamship company (sans the steam). I had gone for interviews with several interesting companies but the reception room of Williams, Dimond had an elegant Japanese doll in a glass case. As I stood there admiring her, a gorgeous Italian ship captain passed through the room and nodded to me.

Williams, Dimond served the shipping lines of many different nationalities, including Mitsui, who had presented the company that doll. The staff was also multi-national -- Russian, Portuguese, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, Italian, Mexican, and lots of San Franciscans of Irish descent. Two of Mieko’s fellow brothel workers in Miss Gone-overseas, Chikako and Izumi, were named for two of my favorite co-workers.

And the other characters in Miss Gone-overseas and where they might have sprung from? The governor general was no doubt modeled on my Pohnpeian boss whose office had the good taste to have that doll in the reception room; Mr Uchida for an old love; the young corporal could be my brother, Eric, whose companionship was the joy of my childhood; and Mrs Okata was probably a mixture of all the nuns I had as teachers in all my many grammar schools.

A fictional character has many models, some real, some from dreams, some from characters met in other fictions. But during the actual process of writing and creating characters, I’m quite unaware of my thieving -- from who or from where. Or only vaguely aware.

Published on November 25, 2013 13:19

October 30, 2013

RAIN

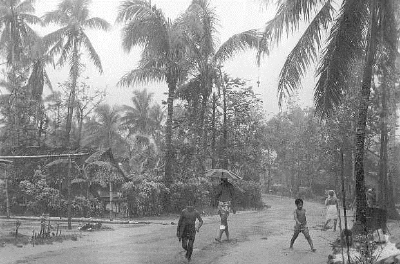

[photo courtesy of University of Hawaii/Manoa digital archives]

During a real downpour everything -- the sky and even the very air -- turns grey. The normally brilliant greens of a tropical landscape are dulled, washed of all color. This image is what I had in mind when I described Jason Tovar’s daily bar-hopping cruises around the town of Kolonia [see Suicide is Timeless, in Overseas:stories]. In fact, this particular street reminds me of Pohnrakied near the Cliff Rainbow Hotel where my character stays.

The island of Pohnpei, the setting for both my novella and my book of stories, has an average rainfall of about 200 inches in the coastal areas, more in the inland mountains. Since the climate is temperate, houses are not insulated -- neither the walls nor the ceiling -- and most roofs are metal, meaning that during downpours conversations must be shouted. My usual defense was to huddle up with a book and a light blanket. Even outside the rain is loud -- raindrops smack, smack, smacking on wide taro leaves, car roofs and umbrellas.

It’s common knowledge that many people are susceptible to winter sadness, that mild depression caused by lack of sunshine. When I lived on this island I was fortunate as my house was built on the edge of a cliff and my vista was the vast Pacific. I truly believe a horizon line, whether an ocean or a desert or a vast prairie, is an antidote to S.A.D. I also found comfort in good company, and San Miguel by the case -- domestic, not the watered-down export.

Jason, my poor narrator, was not so lucky. Granted he brought his problems to the island, and we all know a change of location is rarely the solution to anything. Although I greatly admired the title of Maria Thomas’ 1987 book of short stories -- Come to Africa and Save Your Marriage -- I could not recommend such when I was asked to draft a pamphlet for would-be contract workers. Instead I advised that a stint on a beautiful tropical island would not solve any personal problems. I also advised them to leave their golf clubs at home. There were no links. It wasn't that sort of place.

Published on October 30, 2013 13:56

October 5, 2013

War is Hell

German Catholic Church, Kolonia, Pohnpei, FSM, destroyed in 1944 [photo courtesy of Micronesia Seminar, Chuuk, FSM]

Most of us of a certain age remember being taught in history class about the American strategy during WWII of leap-frogging the Japanese-held Pacific islands. Easy to remember as we had so many fewer wars to study back then; and because leapfrog was one of the common outdoor games we played, out on neighborhood lawns at dusk on summer nights. But in the Pacific Theatre, it was a deadly serious game for both the islands leaped-upon and those leaped-over.

Pohnpei, the island that supplies the setting for my Miss Gone-overseas, was leaped over. There was no invasion by American troops, instead B-24 Liberators began dropping their calling cards beginning in February 1944. In five separate raids that month over 100 tons of bombs, along with 600 incendiaries were unleashed on the civilian town of Kolonia and the nearby military installations.

The immediate consequence of the first and second days of the bombing was a voluntary evacuation of the town [called the District Center in Miss Gone-overseas]. Both the native and the Japanese population headed for the hills, carrying what they could. I was told of this by a fellow I worked for who experienced it as a child. He and his family escaped by canoe to the southwest, through the mangrove swamps separating the main island from the heavily fortified island of Sokehs.

In May of 1944, American battleships (the Iowa, North Carolina, South Carolina, South Dakota, Massachusetts, and New Jersey) shelled the town, the airfields, and several other targets for over an hour. In addition, other air raids were conducted in the waning months of ‘44 and early ‘45. All told, seventy-five percent of the town was decimated as it was mostly wooden framed structures with corrugated metal roofs.

The old Protestant Church survived, as did the shell of the concrete Nambo Department Store which, when I lived there, was used as a machine shop and for storage. And someone pointed out to me one of the few wooden structures remaining, a small house in the Pohnrakied area. Throughout the town were concrete steps that led to nowhere, the footprints of houses that no longer exist, and small concrete columns with Japanese characters proclaiming something -- a school, a shrine?

The German Catholic Church, pictured here, was begun in 1909 and the first mass was said in November 1913. As such a large landmark, it was an early casualty of the American bombing, although reports of its fate differ. Some say that after the initial bombing, the Japanese military finished the job with dynamite, using the material to build bunkers. Others say the destruction was totally from the American bombers. Today only the bell tower remains, a tourist attraction on the grounds of the old mission property, and the subject of many photographs.

Published on October 05, 2013 14:08

September 2, 2013

Tom's Beach

Tom's Beach is one of the very real locations in my story Blue Damsels (in Overseas:stories). My American doctor narrates:

Sylvie’s packed a picnic and we head down the peninsula to what serves as a beach on this otherwise mangrove-locked island. We pass through a jungle landscape of palms, breadfruit, liana, and ginger, all shaded by a high canopy of mimosas and acacias. Then occasional clearings, tin-roofed or palm-thatched houses with carefully tended patches of taro, tapioca, bananas. Groups of small children stop their games to wave, and their skinny dogs bark at us.

Sylvie drives slowly. Our third-hand van is missing shocks and the road’s full of good-sized potholes. Finally, she makes the last sharp turn and eases to a stop in the blinding sunlight of a small, rocky beach. A pitiful little beach and, as usual, deserted.

I slip off sandals and shirt and tuck my wallet under the seat, then hobble over the half dozen yards of coral shingle and fly forward into a shallow dive. Beneath the top few inches the water is cool. I swim across the narrow boat channel and find the large coral whose nooks and crevices are home to a school of small, iridescent blue damsel fish. My other ladies, Sylvie calls them.

The afternoon Air Mike arrival breaks the silence, the sun-polished fuselage like liquid silver as it descends toward the airport across the lagoon, the scream of brakes as it disappears behind the mangroves lining the short runway.

Sylvie pokes my shoulder, tells me I should use sunscreen, and fights to keep the ends of her lava-lava from floating up to the surface. Local fishermen often use the boat channel, so she adheres to local custom regarding modest dress and leaves her bikinis at home. Through the water, I can see the pale moonlight of her thighs.

The island of Pohnpei sits behind behind a fringing reef, meaning no real wave action reaches its shores. Breakers crash against the outer edge of the reef and across the open passes (which are supreme surfing spots -- google P-Pass). In addition, this particular island has an annual rainfall exceeding 200 hundred inches a year, and all that water causes a swath of muddy sediment at the shore, an excellent habitat for a thick swamp of mangrove trees.

Nearby, however, are the most beautiful beaches in the world on the atoll of Ant, a 45 minute boat ride away, a treat we gave ourselves once a year or so. But most Saturdays were spent at Tom's Beach, at the tip of the Nett peninsula and across the lagoon from the town of Kolonia. Tom Maine was my next door neighbor and my best friend -- since he liked beer and gossip as much as I did.

Appears that the day this photo was taken there were three of us (along with the beer cooler) at our decrepit little beach. My daughter must have been on-island -- hence the third chair and the "family" Pentax briefly in my possession.

It was rare for us to have company, except one day when a small flotilla of local fishermen pulled up and deposited their catch on the gravelly beach: reef fish, most no longer than a foot, laid next to each, the row stretching for about 20 yards. Then the highest ranking person went down the row and divided the catch among the participating families. Of course, they offered us some.

The beach has changed (see the photo on facebook page of Miss Gone-overseas) and the road through the peninsula is being paved. Although I always wore a plain black one-piece -- wearing a lava-lava swimming is a bit absurd -- today women at the various resorts do not hesitate to wear bikinis.

What happens to my American couple is way over the top -- but then, Blue Damsels is fiction. Still, I know the generous spirit of the island and its people has not changed.

Published on September 02, 2013 11:08

August 3, 2013

The Game of Go in MissGO

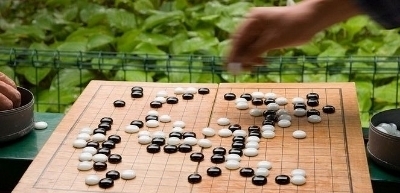

The corporal no longer drives the governor general as the military has taken the automobile. So the governor general stays here. He and Mrs. Okata play Go in the 12-mat room. All day and much of the evening there is nothing but the click of the stones and the murmur of their voices.

Like chess, Go is a serious game. Two players use black or white stones and play on a board marked into a grid pattern. The click sound is produced by holding the stone near the tips of the first two fingers and then snapping the stone onto the board. That snap is a learned skill, rather like learning to use chopsticks, and pretty essential to the formality of the game.

Acquiring territory is the game's most obvious point. Stones are placed at the intersections of the grid, not on the blanks as in chess. One builds territory by placing stones adjacent to each other, by building chains of stones. The opponent then attempts to surround the other's chains with his or her stones. Once a chain or group of stones is surrounded by stones of the opposite color, the territory is taken and the surrounded stones removed from the board.

There are endless variations of the rules: Japanese, Chinese, American, etc. I've played a few times and was reminded of a childhood game I used to play with my brother: battleship. We spent endless hours deploying our imaginary fleets across handmade graphs on school binder paper, and blasting the hell out of each other's navies.

Yasunari Kawabata's The Master of Go, a fictionalized account of a famous 1938 game between an old master and a younger challenger, was published as a serial in the early 1950s. It is said to be his masterpiece. He was awarded in Nobel Prize in Literature in 1968. The novel was not published in English until 1972, the year Kawabata committed suicide.

At the forty-ninth day observations [the engineer] spoke of the governor general's accomplishments and of the days before the military arrived, a difficult but hopeful time for the early colonists. For someone of such few words, he talked at great length. He must miss the governor general and the time they spent together, often looking at maps together like boys playing some game, the islands like Go stones scattered across the blue. Pointing, discussing. Will the Americans come here, will they go there? And the Imperial Navy? Which island, which lagoon conceals our ships this week?

Rather astute of MissGO to compare the islands of the Pacific to chains of stones on a Go board. The U.S. Navy's successful plan during WWII was to move up the chain -- surrounding and capturing. Or skipping over the "high" islands like the one in Miss Gone-overseas, an island rimmed by mangrove swamps and not sandy beaches, making it unappealing to the usual assault tactics and the ease of landing crafts.

After the governor general's death, Mrs Okata is desperate for a playing partner, but MissGO does not measure up -- as Mrs Okata informs her -- the implication being that a country girl is not sophisticated enough. It is true that there is never a mention of high-brow cultural pursuits such as calligraphy or flower arranging or the tea ceremony, but the diary of this unsophisticated country girl is full of mono no aware. She fully embraces the impermanence of life.

And as for the game of Go, doesn't MissGO prove in the end that she is, in fact, a master of the game?

Published on August 03, 2013 13:13

July 6, 2013

The Village Hotel

The Fairmont, The Imperial, The Metropole, The Royal Hawaiian, Raffles -- classic hotel names that bring instant association with San Francisco, Tokyo, Hanoi, Honolulu, Singapore. And travelers truly familiar with the western Pacific will instantly associate The Village Hotel as the premier hotel of Micronesia.

As pictured here, the hotel's main building housed the bar and open-air dining room with views out over the lagoon, the ocean, and to the distant rock formation of Sokehs known as the Diamond Head of Micronesia. The guest rooms, separate bungalows, were scattered fore and aft of the main building -- and all perched along a peninsula's narrow ridgeline.

The place was established in the early 1970s when Bob & Patti Arthur, a young California couple and their four small children, one a lap baby, arrived on the island of Ponape in the Trust Territory of Micronesia (as it was then). They negotiated with a handful of landowners for a lease, for a spit of land on which to build the hotel of their dreams. And build they did -- in the local fashion, with local materials and thatched roofs -- on a grand scale (though modest compared to the structures of the first named).

When I lived there in the 1980s it was SOP for a good many folks who lived in and around the town of Kolonia (then the capital) to make a weekly trek out to The Village -- an axle-jarring drive along the potholed circumferentia road (since paved). We went when the power was off on Saturdays for lunches of French Dips or real hamburgers. We went for special occasions, for candlelit dinners of Mangrove Crab or Bouillabaisse (yes, with real saffron) or New Zealand Rack of Lamb. But most often we went for their outstanding Sunday Brunch, savoring warm beignets while we decided between Eggs Benedict or scrumptious banana pancakes.

For almost 40 years Bob and Patti Arthur ran the most spectacular establishment in Micronesia, and in the process they hired and taught hundreds of local workers the skills of hospitality and cooking. Sadly, The Village Hotel closed a few months ago. [Google to see more pictures before they all disappear.]

The dining room and bar were as popular a gathering place as the roof of the department store was in my Miss Gone-overseas; and my pieces in Overseas: Stories would be lacking in versimititude if I had neglected using The Village as a locale. Under the Flame Tree opens with an American visitor picking up her room key and receiving a note from the wife of a new "friend" -- and, later, there's this brief flashback:

Only a week ago Geneva had sat across from this child at one of the hotel dining tables, having been invited to join their Sunday brunch en famille. Leialoha with the sulky, sultry beauty of a Gauguin ingenue, sipping a coke float. The waitress had just set down a plate of beignets to hold them while studying the menu when a loud, shrill cry pierced the room. Heads turned toward the American ambassador’s wife. A gecko had fallen from the rafters, landed on the floor, and in it’s fright had scrambled up her leg, mistaking it for safety.

And Maria had turned to Geneva: “I have been wanting to meet you,” she said, “and to my surprise I find you are already Valerio’s friend.”

[Maria -- for those who have read Miss Gone-overseas -- is the child Mariko who was born at the house on the river.]

I remember my first meal at The Village: a mid-week, mid-afternoon, kitchen is closed between shifts snack. I had arrived on-island only a few days before and my sister had taken me to meet her great friend Patti. Here's Patti's excellent recipe for a tuna salad, island-style: open a can of tuna in oil and without draining, plop it on a plate. Top with a shake or two of Tabasco and a hefty glug of shoyu. Then pinch off pieces of cold, cooked breadfruit to use as scoops: nom nom nom.

Published on July 06, 2013 15:15

May 31, 2013

CALL ME MIEKO

Twenty years ago a b&w xerox of the Balthus painting, Japanese Girl with a Black Mirror, kept me company as I began writing what was eventually published as Miss Gone-overseas. With a colored pencil I doctored the woman's white sash; I made it red -- instead of mimicking the painting's red cloth on the small table.

The image of the Japanese girl on her knees and her long reach for something she wants -- perhaps merely to adjust the mirror -- is what makes her "my" Japanese girl. Miss Gone-overseas isn't sure what it is she reaches for, but she reaches nonetheless. [The curious can learn what her reach achieved in the first piece in my book Overseas: stories.]

It's a common literary envy, that of Melville's bold opening: "Call me Ishmael." One cannot expect such an opening gambit from the pillow book of a Japanese woman in the World War II era. My Mieko never introduces herself. In the two most famous "real" pillow books one never learns the names of the narrators in the text, but only in the titles given by the translator and/or the publisher: i.e., The Pillow Book of Sei Shongaon, and in the English translation of Murasaki Shikibu's with the subtitle, Her Diary and Poetic Memoirs. I do admit to considering and discarding Mieko's Diary as a title.

I am curious as to how readers feel about a narrator who remains nameless. To keep her company I also left nameless two other characters, the governor general and the corporal. My personal library diminishes each year (by choice), but one keeper is Peter Handke's The Left-Handed Woman, an exquisite little novel with nameless characters: there's only the woman, the man, and the child.

It wasn't until the final rewrites that I contrived a way for my narrator to name herself: one brief sentence near the very end when she discards her name to assume another. The name I chose for her is quite similar to my own (the discarded nickname of my youth: Micki). May I borrow a phrase? Mieko, c'est moi.

Published on May 31, 2013 08:36

May 11, 2013

NOWHERE SLOW, etc

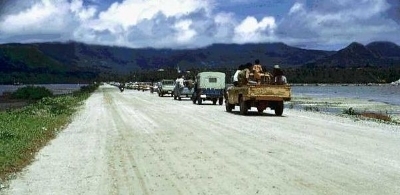

On the island of Pohnpei there is no such crime as Grand Theft Auto. All that can be charged is Joy Riding because the thief cannot form the intent to permanently deprive his or her victim of his or her vehicle. The borrowed vehicle is driven around until it runs out of gas, then abandoned, and eventually recovered by the owner.

On the island of Pohnpei there is no such crime as Grand Theft Auto. All that can be charged is Joy Riding because the thief cannot form the intent to permanently deprive his or her victim of his or her vehicle. The borrowed vehicle is driven around until it runs out of gas, then abandoned, and eventually recovered by the owner.On an island the size of Pohnpei one can only drive in circles. And on a island that size one can only drive slowly. One exception being the half-mile causeway between the airport and the town -- pictured here on an airplane day with everyone returning to town. On non-airplane days, when the strip was empty, I could floor it, easily reaching 60mph before stomping the brakes and down-shifting to make the sharp right-hand turn up the hill to the town proper. My excuse: it blew the gunk out of the carburetor. The real reason: I like driving fast.

I was reminded of all this because of a recent book: Nowhere Slow: Eleven years in Micronesia. The author, Jonathan Gourlay, taught at the local college. My mama taught there, too. A couple of times I subbed for her when she was off-island. One of Gourlay's pieces celebrates the illustrious typewriter of a deceased fellow teacher. He calls him Pete -- but I know who he means. Another is a funny piece on when girls must wear trousers so as not to break the great taboo against showing their panties. Another is a lexicon of dirty words. And another gives advice on raising children there: "Your kid may be with a troop of other mostly naked children in the jungle, but she is safe. Just remember to de-worm her regularly."

Gourlay went native and I did not. He had insights into the culture I had no access to -- he married there and had a child. He had in-laws; he was a participant in local feasts. I was merely a guest -- my nose pressed to the glass of the aquarium. There were things I could see, but could not understand.

I rank Gourlay's book with my other favorite "gone native" books: James Hamilton Paterson's Playing with Water (about the Philippines) and J. Maarten Troost's The Sex Lives of Cannibals (about Kiribati).

It seems harder for women to go native and come out the other side and write about it. I love Geisha by Liza Dalby, Marjoire Kinnan Rawling's Cross Creek, and Karen Blixen's Out of Africa. But these women did not go native. Dalby spent only a short while as a pretend Tokyo geisha; Rawlings kept one foot in literary NYC while running her backwoods-Florida orange grove, and Blixen lived in pseudo-European luxury as she managed her Kenyan coffee plantation.

Nearly a decade separated my being in Micronesia and Gourlay's being there, but some things didn't change much. Gourlay bounced around in a pickup listening to Juice Newton at full blast -- my sister and I bounced around in a pickup on the same rutted roads listening to Juice Newton at full blast:

Playing with the queen of hearts

Knowing it ain’t really smart

The joker ain’t the only fool

Who will do anything for you.

Gourlay loved the island and left. I loved the island and left.

Published on May 11, 2013 08:36

April 19, 2013

Backgound: cover and story

[vintage photo courtesy of Kurt Bell]

The cover of Miss Gone-overseas is a vintage photo of a group of kimono-clad women that wraps both the front and back of the book. The women appear to be on some kind of outing -- water and mountains in the background. My guess is Lake Biwa, northeast of the old capital of Kyoto and a popular tourist destination in Japan. I am grateful to these anonymous women for acting as stand-ins for the brothel workers in my book, and to Lake Biwa for standing in for the island of Pohnpei.

The title, Miss Gone-overseas, is a translation of karayuki-san -- the term for girls and young women who were sent as prostitutes to Japan's Southeast Asian and Pacific Island colonies. For the most, they were unsophisticated and came from poor agricultural or fishing families who sold them to brokers who, in turn, passed them on to commercial brothel owners. Keep in mind that prostitution was legal in Japan until late in the American post-World War II occupation of that country.

My book was written as a first-person narrative in a form known as a pillow book (makura no soshi) -- a notebook or collection of notebooks, much like Western diaries, recording events and impressions from the writer’s life. High, wooden pillows were necessary to preserve the complicated hair-dos of pre-modern Japanese women. Often these pillows were hollow, roomy enough for makura no soshi among the other necessities -- not unlike the drawers of our modern bedside night stands.

I first encounterd pillow books as a literary form in my early 20s at the Smiley Public Library in Redlands, California. I ws still under a spell of enchantment from reading Murasaki's Tale of Genji and I was seeking more of the same. In the stacks I found The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon, also written at the end of the 9th Century and beginning of the 10th Century and also by a lady-in-waiting at the royal Japanese court. This was the Heian Age, a high rennaisance compared to European countries then deep in the Dark Ages. So, from a court lady's impressions and gossip I modeled my musings of a lowly brothel worker in a far corner of the Japanese Empire on a tropical Pacific island during World War II.

Published on April 19, 2013 14:22

April 5, 2013

skirts

The other day -- International Women's Day -- groups of dancers performed on Pohnpei, each group wearing coordinated, bright cotton skirts such as these. [pictures available on the facebook page of my former employer, the US Embassy Kolonia, Micronesia ]

In my Overseas story, Field Notes, the wife of Salvador wears several layers of skirts. She goes topless in the privacy of the family compound; should a non-family member arrive she merely pulls the top skirt up to cover her breasts. Near the end of Miss Gone-overseas the narrator begins to go topless when she's working alone in the garden.

Topless was once the norm for all islanders -- men and women. Christian missionaries in the last part of the 1800s introduced native women to the Mother Hubbard -- long sleeved, high necked, and a skirt to the ankles (with or without a waistband). Only the "converted" went for this hot tent of a garment. With the arrival of imported cloth, many women in the villages replaced traditional natural fiber skirts with a yard and a half of fabric, a lava-lava covering from waist to ankles. During Japanese colonial times, women in the district center adopted kimono or imported western-style dresses.

And when I was there, it was the norm for all Peace Corps girls to wear the traditional cotton skirts and T-shirts. However, one could always tell the arrival of a new group of volunteers by the mud-spatters on the backs of their skirts. They had yet to learn the technique of walking on muddy trails and streets in flip-flops: one must slide the feet forward, not lift them. This results in no mud being flipped up on the back of the skirt. Added benefits: a slower gait to match the seductive, tropical landscape and a sexy, sultry swing to the hips.

Published on April 05, 2013 09:09