Adrian J. Walker's Blog, page 2

October 24, 2014

More than a Marathon – Rachael Bateman tells us why she runs so far

When I was writing The End of the World Running Club, I got a lot of help from a group of runners and ultra-runners, who told me what it was like to run very long distances and why they ran them. One of them, Rachael Bateman, went a step further and agreed to write this brilliant description of a 50-mile race she recently ran.

Thanks Rachael, over to you…

More than a Marathon

What? You ran that far? How long did that take you? You really ran that in one go? These are the responses I get when I’m asked what I did at the weekend if I’ve run a long way. People’s tones range from disbelief to mockery, through awe, respect, doubt and ambivalence. Few really understand what I do, although I would love to be able to communicate it and give some kind of insight into what it means to run more than a marathon. This is part of why I started to write about my running experiences which escalated quickly from a couple of short runs a week to training hard for long distances. I went from two 5k runs a week to ultra-distance running in 18 months.

A marathon is far. I think, at least in modern Western society, we’ve benchmarked that magical 26.2 miles as very far and we place it on the outer limits of normal in terms of an achievable physical challenge for the majority of people with reasonable physical fitness and perhaps youth and determination on their side. But what about more than a marathon? Where does that even come from and why would anyone want to run that far? What is the gain? I don’t run for accolades and praise, although a recent survey I completed on my sport psychology suggests I thrive on recognition for my achievements. But isn’t that human? I’m not fast enough to win anything yet so why would I run 40, 50, 100 miles, and how?

“…when I started, I struggled to corral the concept of 5k in my mind.”

The first thing I will say is, I never consider running a long way in one thought. I mean, I never hear the gun go or the start declared and think, I’m going to run, say, 50 miles. That would be like being told, “you will live for the next 50 years!” expecting to picture clearly how that will pan out. No one can. So in terms of running, when I started, I struggled to corral the concept of 5k in my mind. Now of course I can and I run it in a fairly average way. I’ve got a reasonable idea of how that 5k will go. Up to 26.2 miles, I have a reasonable idea of how a run will go. However, when it comes to more than a marathon, life within the run evolves in a very different way that in my opinion is impossible to comprehend fully until you’re in it and running. I of course plan carefully beforehand how I will run each section of the journey, like I did for the 50 miles I ran recently. I recced this race between the checkpoints on my own and with friends in the weeks leading up to it, calling to mind how each of the sections would likely feel in terms of effort and psychology as I sat at home with a glass of wine marking out the map. I had a goal time, 12 hours and I planned my pace between each checkpoint rigorously in order to meet that target. I chose the right equipment, hydration and food but so much of ultra-distance running is about dealing with what comes while on the journey, which I was reminded of when my plans began to unravel around mile 32 on this latest race.

“…ultra-distance running is so much about the mind.”

I can quite comfortably run 30 miles and not feel intimidated or overwhelmed by it. I don’t see this as anything to brag about particularly, it is just a fact that is part of my make-up as an athlete. Frequent checkpoints and crisp, cloudless daylight in that first lot of miles are all great for your mind and ultra-distance running is so much about the mind. Positive mental attitude and emotional resilience are key factors in managing the physical strain when your legs and shoulders are aching and when the lazy, gluttonous monster of tiredness starts to eat away at your mind in the dark. And of course darkness does come on ultras because of their length.

Night. At the same time both vaulting and smothering, night blinkers you with a tight focus that can bring resolve as much as despair. So when I was grouped with 4 men just after dark at the mile 27 checkpoint, I was very pleased. They’d all kept a great pace earlier in the day and I knew at that point, my head was losing the strength I needed to dig in and keep the pace I had planned for the second half of the race. I knew I needed the challenge of their pace to bring me through at least the next 5 miles until I was settled into a rhythm again. So with a mixture of banter and assertiveness, I made sure they took me into their grouping. Prior to this, I had analysed those around me while I prepared myself quickly to go again. None of us could leave there alone due to the rule on that race, stipulating that you have to be grouped for night running. I was not sure of the other possibilities for a grouping as I cast my eyes around the marquee housing the check point. I wasn’t sure whether I felt confident in the other people I had observed as we milled around: a disjointed, tired community of runners, sizing one another up in the hazy yellow light, shoving the calories and swigging sugary tea.

“…as my team mate lay in the frosty grass, writhing with stomach cramp and vomiting profusely, a mixture of emotions took hold of me.”

Plunged into darkness in the woods outside the checkpoint, I swigged the last of my tea and fastened the mug to my pack. We ran on, me and the four men, getting to know one another on the way. It soon became clear that only a couple of us were confident of the route and could map read. It turned out I was one of the stronger runners too and I pushed us on towards the next big climb, keeping the compass bearing in mind for the run off the summit while casting my thoughts forward to the route but not the distance ahead. We yomped up the hill and found the rocky slope down to the next checkpoint. As we left the hill and ran through the fields, we could hear music and the singing along of the people manning the checkpoint. We could soon see the lights of the barn where they were waiting for us with tea, tiffin cake, biscuits, jelly babies, Bovril, soup, hot chocolate… Two old farmers were somewhat incongruously playing Scrabble on an iPad while we ate and drank and refilled bottles with water. It was slightly surreal. It was here, at mile 32 that I became aware one of my team was unwell. He was struggling with his stomach. A common problem when you run long distances. When he’d been sick, we continued and by the top of the next hill at mile 35, he was deteriorating rapidly. Our pace had slowed on the path to this point and other groups had caught us up. I could see their lights and hear their voices close behind us. I was aware I could lose my place as 6th lady if we didn’t move. Primitive selfishness wells up and subsides like a dangerous tide at times like these. So as my team mate lay in the frosty grass, writhing with stomach cramp and vomiting profusely, a mixture of emotions took hold of me. I wanted to run on alone and leave them all, run my own race. I wanted my team mate to be safe though and I realised that I had to dig deep and encourage him on to safety 3 miles away at the next checkpoint, where thankfully there was a medic waiting. It was very hard to leave him there, unsure whether he’d finish the race later, or even be ok.

“Around my feet, scarab beetles darted and in the heather, the faces of fairies peered out at me.”

It was so cold. The sky was black, cloudless, still. We ran on from where we’d left our teammate. We held a strong pace, chatting, joining with and overtaking runners who had overtaken us earlier. Then 40 miles into the race, we hit the moor. Running in the direction of the star I had been told to follow by a fellow runner over breakfast that morning, we fell into a rambling silence where my mind trickled out through my exhausted gaze over the heather and the peat hags. I was imagining things that were not there. Hallucinations were always something I thought only happened at much longer distances. To my left were phantom whitewashed Spanish houses I could almost touch. Around my feet, scarab beetles darted and in the heather, the faces of fairies peered out at me. It was bizarre; not frightening, just bizarre. I knew that what I was seeing was not real and when I reached the road and we began to chat again as a group, I found the experience amusing. I find it interesting how the mind can buckle and shift and move under pressure and how quickly it can return from the edge. Ultra-running shows you this.

The last 10 miles were painful. Everything hurt. My hip flexors had taken a battering on my right hand side and the final descent of the cruellest, steepest hill was limped. The slow drag into the finish at race headquarters a mile later was wearisome and starkly comforting. I’d run ultra-distance before and got into the car to go home feeling empty and overwhelmed by anti-climax. Not this time. There was a huge sense of achievement. I knew I’d done well but more than the position, it was the journey travelled that was both critical to my desire to race and my accomplishment at the finish. Self-indulgence is the preserve of the ultra-runner, I believe. We are all looking for meaning. We are all looking to understand our limits. Our blogs analyse our approaches to life and our training; they celebrate human endeavour and the world out there under the sky. This is why we run far; because we can and because something in our make-up compels us to do so.

Rachael was born in Johannesburg, South Africa in the mid-1970s. Personal and political difficulties drove her English parents back to the UK and so from the age of three and half, she grew up in Wales, the place she calls home.

She now lives in England with 2 brilliant children, teaching English to teenagers with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties. And guess what? She also runs and writes.

Protected: More than a Marathon – Rachael Bateman tells us why she runs so far

This content is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

September 1, 2014

Not in England

In a week or so, right around the time when a lonely Tibetan hill farmer lines up his iPhone to perform the world’s final ice bucket challenge, Scotland will vote on its independence. The following are my thoughts about what this means to me. Most of this remains raw and unedited because that’s how these thoughts exist in my head. As will become evident, I do not have a particularly political mind, but I have spent most of my adult life grappling with the neurosis that comes out of being half-English and half-Scottish, so the vote will affect me one way or the other. I apologise if this is long and rambling – this is just what’s in my head. Like I say near the end, I’m not trying to side with either YES or NO voters.

In a week or so, right around the time when a lonely Tibetan hill farmer lines up his iPhone to perform the world’s final ice bucket challenge, Scotland will vote on its independence. The following are my thoughts about what this means to me. Most of this remains raw and unedited because that’s how these thoughts exist in my head. As will become evident, I do not have a particularly political mind, but I have spent most of my adult life grappling with the neurosis that comes out of being half-English and half-Scottish, so the vote will affect me one way or the other. I apologise if this is long and rambling – this is just what’s in my head. Like I say near the end, I’m not trying to side with either YES or NO voters.

My dad was born in a fishing village on the West Coast of Scotland. My mum was born in a council estate in the North of England. My mum grew up and moved to Scotland. My dad took a boat to Australia, then my mum moved to Australia. They got married and had my sister and lived in the bush suburbs of Sydney, where I was born. My dad was a postman and joined the bush fire brigade and my mum taught drama to local kids. Then they missed home and moved back to the United Kingdom. They tried Scotland first but there were no jobs so my dad got in a van and drove off looking for one. He found one in the south of England. So that’s where we moved. That’s the first memory I have of a landscape that was home; a land where I lived.

The house he bought for us had no roof and no heating and was next to a grave yard. We all slept in the lounge by the fire. The village was what you imagine English villages to be. It had a haunted pub and a pond and a vicarage. Dad put a roof on the house and we stayed there for a while. After a few years we moved to a village nearby. I don’t know why. My sister got a scholarship to a music school in Manchester, so then we moved north to Chester. Chester is a Roman City on the border with Wales – the urban myth is that it is still perfectly legal to shoot a Welshman with a bow and arrow after midnight. This, despite the face that – as with Mogwais – any time is after midnight. When people ask me: where are you from? I say Chester, because that’s the home I left when I was eighteen. I moved to Leeds and then to London, where my sister was based. She had joined an orchestra and was touring all over the world. Then she moved to Bremen – a town that, a few years before, had been on the happier side of a wall that divided Germany. I moved to Gibraltar. Gibraltar is a strange rock that dangles from the south coast of Spain – “the last colonial testicle in the British Empire” as a friend once remarked. It borders with Spain and there are arguments and name-calling and people spit at each other. I lived in Spain and crossed the border every morning, passing mulletted smugglers hopping the barbed wire fence with cheap cigarettes in plastic bags.

My parents moved house again and my sister moved to Singapore – another colonial testicle, but a cleaner one. Now she plays in an orchestra of musicians from all over the world, people who are more likely to be stereotyped based upon the instrument their play than the place where they grew up. I moved back to London, then I travelled to Asia and drove a yellow Ford around Australia with an Irish friend. One night, a fish cook in Kalbarri asked us how an Irish woman and an English man could stand to travel together. He found it hard to believe, given our countries’ pasts. He found it even harder to believe that we slept separately, which seemed odd. I visited Sydney and thought I might stay there for good in the city of my birth. I thought I might find an identity there. I sat outside the registrar’s office with a brand new passport and Bruce Springsteen’s My Home Town came on the radio of my Ford. That week I saw more cars with my initials in the registration plate than seemed likely. I thought it was a sign. I thought I might stay, I thought I might make Sydney my home when I’d finished travelling.

Then I went to New Zealand and lived on a beach for a month. I started writing a book about two Carthaginian soldiers who took to sea because it had no borders. On the beach where I stayed there was a turf war (literally) between two rival grass-cutters. One woke up early and put metal spikes in the ground of the other one’s patch. I wanted to run around the coast but I was told I had to ask the Mauris’ permission first. They owned the land. I never found the courage. Instead I tried to fish when I wasn’t writing. I caught nothing and finished about a third of my book.

Then it was time to go home because I had no money. I didn’t move to Sydney. I moved to Edinburgh where my friends had moved, en masse, after leaving school. One of them, Fraser, was born in Scotland to Scottish parents and has lived in Scotland for over half of his life. He has a North-West English accent and says that Chester is where he’s from, like me. When we were eighteen, Fraser and I started spending our Summer holidays in Newquay, learning how to surf. The first time we drove all day until we crossed the invisible line into Cornwall and saw a road sign emblazoned with graffiti: YOU ARE NOT IN ENGLAND. Cornwall remains my favourite place in the British Isles. I can’t think of Newquay without smelling surf wax, banana milkshakes and pasties in salt air. I can’t think of Sennen without thinking of the gigantic cliffs that mark the end of a small island and the beginning of a deep, wide ocean, or remembering a pub called the First and Last Inn and the words Fraser used to describe a man who played darts by our table: he has the fighting eyes of a celt. The words made me feel a strange mix of belonging and trespass – the same thing we felt when we entered the ocean for the first time with our boards tucked under our arms, eyed by surfers for whom this was their beach. A border existed there and we had no option but to cross it, uninvited.

Another border.

I found Edinburgh easier to live in than London. I wanted to work in a cheese shop and write a book, but I got a job in an office instead. On my first day, someone made a snide remark about me being English. Then he found out I was half Scottish and wanted to be my friend. I left a year later and wrote a different book about a one-legged hitman. I stayed in Scotland for ten years and married a girl from Orkney. It’s windy in Orkney and they have no trees. Every Christmas they play a game called the Ba’, where two teams try to get a ball to the opposite end of the town – only people from Orkney can play and the team you’re in depends on how you first arrived on the island. The game can last all day. My wife left Orkney to study in Glasgow, and then in Cambridge. We met in France and fell in love at a music festival in Belgium after teaching some locals how to say ‘Fanny Baws’. That wasn’t the only reason we fell in love. We had two children, both born in Scotland. My daughter speaks with an English accent, despite only having been there a couple of times. We can’t work it out. Then we moved to Aberdeen. Last month we moved to Texas, a large state in a large country that borders another large country. Texans ask me where I’m from, then don’t really understand when I tell them. My Mum died a few years ago and my Dad now lives on a boat in France. He’s renovating it, like he’s renovated everything in our family, including our roofless house. In the yard he’s made friends with an Irishman and a Pole. Soon he will set sail onto seas that have as many borders as the land he leaves behind.

No breed of nationalism or patriotism exists in my family. I feel no pride about being Scottish, nor English, nor European. What I feel is a vague sense that I used to belong to a group of people who were doing things right when the rest of the world wasn’t, people that had, despite their differences – and despite how plain fucking difficult it is to be alive and run things like countries on a spinning rock in the cold void of endless space - pulled together and were starting to laugh at themselves and feel comfortable on the same dirt. But I don’t feel proud to be British. At times it’s a struggle being proud of my species, let alone the patch of earth I have walked on for most of my life.

In a couple of weeks, Scotland will decide whether or not it wants to be an independent country, no longer part of the United Kingdom. By Scotland, I mean anyone who lives in Scotland at the time of the vote. Sean Connery doesn’t get to vote because he doesn’t live there, although many people believe he should be because he once played James Bond – a spy who shot people and fucked women for England.

I’m not writing this in an attempt to sway anybody’s thinking, because I have nowhere to sway them. I don’t know what the right answer is; I don’t have any water-tight political arguments for saying yes or no – I’m not very good with politics at all, in fact, because, like religion, like football, like any tribal construct, politics generally demands that you pick a side. I don’t like being on a side. If I was voting, my vote would be about what I feel, which I suspect is how most people will be voting on the day, despite the assertion that it’s all about Tory rule or Westminster or Trident or public school boys or the BBC or all of the above. That it’s not about Braveheart. It’s not about a man shouting freedom with his intestines around his ankles. It’s not about a man who killed children and wore a belt made of human skin.

Sometimes I love Scotland. Sometimes I hate it. The same goes for England. They’re both what I have, not what I want. I want somewhere warm with hills and lakes and good beaches and safe roads, good wine, good music and people who don’t get hung up on history or call each other names. I don’t believe Scotland would be better on its own. I don’t believe we would be better together. I don’t believe much, if you really want to know. All I have, really, are hopes and ideas. Belief is what happens when those things harden and crack.

I don’t have the answer. I know that if Scotland votes yes, I’ll feel the same feeling that I get crossing the border into Cornwall. I’ll also feel less bad about being English the next time I’m in Scotland, because I will no longer represent a problem to some of the people who live there. If the vote is yes, I suspect more people will want the same thing elsewhere. Maybe in Cornwall. Who knows, maybe in Yorkshire. I hope that whatever manifests itself is aimed at freedom from the current political system rather than the erection of another border.

Scotland is whisky and skies and lochs and banter, and guilt-free pride of being a part of a blameless tribe. I don’t know what England is, Wales and Northern Island even less. I know what England used to mean for me – it was similar skies and gentle brooks and quiet talking in dark pubs, frothy beer, sunshine and village fetes and old men with distant looks in their eye. I can’t find that idyll to pass on to my children. I can’t even find the Scotland that I’m told exists, or that could exist, if only people would stop being afraid and do what other people want them to do.

I hope people vote for the right reasons and I hope that people on both sides of the border – which is, whatever happens, now a fast darkening line – are better for the outcome.

If all this sounds like apathetic, badly thought-out bullshit then you’re probably right. But here’s something: Yes-voters don’t like Westminster and, guess what: neither do I, neither do most people in England, or the BBC of that matter. Maybe the best that can come of this is that more people realise this fact and take action – it would be a shame if we have to do it in small teams rather than as one united front, but maybe we’re not grown up enough for that yet.

I don’t like the power that corporations have and I don’t like the power the media has. I don’t like what we’re becoming – I mean us: humans, not Scots or Brits or Angles – us. Give me a referendum on the powers of the press, or the way we choose people to lead us, or taxation of the corporations who have hijacked the mythologies that once united us, or the NHS, or the things we should be prioritising as a species on the brink.

Ask me a yes/no question on those things and I might be able to give you an answer.

August 22, 2014

The Passion

A friend told me that someone asked him: “What’s your one true passion in life?”

He faltered. He didn’t say the thing he thought he was supposed to. And that worried him.

Here’s what would go on inside my head if somebody asked me that:

This person is asking me if I have passion.

Not just general passion, but something I’ve picked out that is specifically my one true passion.

Having passion seems important.

There is such a thing as a ‘true’ passion.

That means there is such a thing as a ‘false’ passion.

Other people obviously have this true passion.

Others have false passion. Others have no passion at all.

If I don’t have a true passion in my life, I’m only half a person. A zombie. I’m worthless.

Either that or I’m a lier.

I need to say that I have a true passion in my life.

If I don’t say that I have a true passion in my life, this person is going to be disappointed in me.

I don’t want to seem disappointing.

Maybe I should ask them what their passion is first.

Asking them what their passion is will make it seem as if I’m stalling.

What is ‘passion’ anyway?

Passion is love. Passion could be sex.

I can’t say “sex”.

Passion shouldn’t be fleeting. It should be constant.

Writing should be my one passion. I’ve chosen to do it. I feel surges of passion when I get it right. I feel great when I’ve finished something.

But writing is hard and I think it’s always going to be hard. I don’t naturally return to my desk to ‘activate passion’. I don’t do that yet.

Should passion be hard?

Maybe passion should be hard.

Maybe passion shouldn’t be hard. Maybe it’s something you do without thinking about it, because you love it.

I could say “sex”. Maybe they’d go away then.

What is it that I return to?

Is that what passion is? Something you always return to?

I think I’m passionate about running.

Running is hard.

I always play guitar. I could play guitar all day without effort. No effort at all.

I’m passionate about playing the guitar.

That’s it!

But I don’t make money out of playing guitar. Nobody hears me play guitar but me and my family, from another room.

I’ve failed at my passion.

Should making money be a measure of whether or not you’re ‘doing’ your passion?

I can’t say that playing guitar is my passion because I don’t have anything to show for it.

I can’t say that writing is my passion because it seems like a lie.

Whatever I say is going to sound disappointing.

Etc, etc…

Does any of that sound familiar?

Our days have become filled with questions like these. They’re hybrids; strands of Eastern philosophy weaved through the Western culture of self. They seem to be universal, questions that bind us to some bigger part of ourselves, something that gives us a sense of what it might feel like to be spiritual in a world where we’ve lost the ability to feel that way naturally. They don’t really make sense outside of now.

Vocation is a word that’s used a lot. It’s from the Latin vocātiō, which means “a call” or “summons”. I know that because I just Googled it. I don’t speak Latin.

Joseph Campbell said: ‘follow your bliss’.

What bliss would a coder follow if she was born in 1514? What would call her?

What would she do without a computer? Apply logic?

And before logic was a thing, what would she do? What would call her? Counting?

And before numbers?

Would Bach be a DJ now? What would he have been in a cave? Would the same thing have called him to produce the music of the universe using rocks and dried animal gut?

Would people have cheered? Would they have wept when they heard him play a fugues on a tree stump?

Maybe your vocation – your passion – is just a blend of distractions applied using the conventions and technologies of the time in which you live. So passion, really, is just a pleasant distraction.

Stop being self-consciousness, ignore the modern idea of PASSION + INCOME = SUCCESS and you’ll find a dozen things that you’re passionate about. Kids, family, laughing, seawater, open skies, swearing, hills, films, noises, words, shouting, silence, kicking, leaping, lying still, smelling oranges, having sex.

Your passion is whatever happily distracts you. Whatever makes you happy. Whatever doesn’t feel like work.

That’s not what people want to hear, though.

Just say sex.

May 12, 2014

How you feel about running

A few months back, I asked you for some help with my second novel, The End of the World Running Club, which is published next month. I wanted to know about your experiences running – especially from those of you who run long distances. I wanted to know how you feel about it, what moves you to run and what pushes you through that extra mile when the going gets tough.

I was really pleased with the reaction, so thank-you to everyone who shared their stories! All of you will receive a free copy of The End of the World Running Club in the format of their choice when it’s released.

Below are some of your excellent responses…but first, here’s my favourite story that somebody sent me…this is what it’s all about. Thanks again, and if you haven’t already supported my Thunderclap for the book’s release, I’d be really grateful if you did so here: https://www.thunderclap.it/projects/11552-end-of-the-world-running-club

We were working in Shetland last year when one of my electricians made a remark that he could run a marathon no bother! Needless to say I challenged him to run to work the following day, which was 28.7 miles door to door. At this point we were enjoying a pint in the local pub. He duly accepted the challenge and headed off to the local shop to buy a few mars bars and energy drinks. I was still unsure as to whether he’d actually go through with it but got up at 5am anyway to see him off. He completed the distance in 6 3/4 hrs, which for someone who has never exercised in his life is pretty impressive. Even more impressive was the fact that he was wearing board shorts, boat shoes (he’s an avid sailor) and a polo shirt. Just goes to show that if you have that mental grit & determination about you, you can achieve anything, regardless of your physical shape.

Can you give an account of the longest distance you’ve ever run in a single session and/or over consecutive days? What physical and psychological effects did you experience?

…12km. Sad I know but true. It was the longest distance I ever ran. I felt amazing after it…

35m, along the sandstone trail…I’d been promised 32m…I mostly cried over the last 3 miles.

…London to Brighton 60 miles in one day. State of mind? Acceptance. You have to do it….

…it felt like you could actually feel the ball of the thigh bone rubbing around the socket of the hip. I seemed to become much more aware of the mechanics of the body as they gradually got worn down..

…wet feet. Think of your feet after getting out of a hot bath and triple it. White, wrinkled and very soft. I jumped off a gate with sodden feet and felt the skin shear on the ball of my foot when I landed…

…It’s much harder in the dark…

…3 marathons in 3 days north cornwall coast…Pain wasn’t enough to stop…If I didn’t finish it would be like an itch I couldn’t scratch and would have to have another go…

How does your mental/emotional state change over long distance? I’m interested to know what happens to your thought processes and feelings when you push yourself out of your comfort zone.

…I have little discipline…personally I think its my stubborn nature that works against me sometimes because halfway through a run I think – oh what the f.. I have no reason to be here this is silly…

…little voices in my head saying “you know you don’t have to do this, you can stop” but the other voice saying “come on you’ve come this far, it just hurts a bit, just get on with it and finish”

What state of mind do you find to be the most conducive to running extreme distances? Can you control this?

…always remain focussed on the end and do not deviate from it…not finishing has never been an option yet…

…zone out of everything apart from the race/run and focus on nothing but finishing…

…you can do this whatever happens. Other people have done it, there is no reason why you can’t…

Have you ever hallucinated whilst running?

…one time by left eye went a bit blurry and I couldn’t see straight…

…I did feel what i can only describe as the madness people have described having in the desert…

Have you ever broken through multiple walls whilst running a long distance? What gets you through them?

…not sure I’ve ever really hit a wall. I tend to gradually slide, rather than slam…

…say to myself man up and keep moving and get it done. Then rest and drink beer…

…sheer pig headedness/stupidity…

…the need to not be beaten. I can’t let my body win, or the distance win…

If you were facing a month of running a marathon or more every day, what would you see as the single biggest obstacle? How would you counter this?

…I ran a half marathon every day for the first week….the biggest obstacle I found was not physical but mental

…your body is under so much more stress than it is used to and some things will break down. Pain then starts messing with your head and doubts creep in. If your head isn’t focused then I think you’re stuffed…

…Chafing. I hate chafing. I have a very carefully organised system of lubrication…

Do you run better on your own or in company?

…my own company bores me silly. I end up talking to birds, trees, singing rhythmic songs in my head, then that makes me cross too. I need to be distracted from the repetitiveness. If I don’t, I dream of the repetitive action of running and then struggle to sleep because I’m maintaining my pace then too…

…if I’m running with other people, I really rely on them to keep my emotional balance. Otherwise my inner couch potato starts screaming and the urge to stop and lie down is overwhelming…

…longer runs or races I want to go at my own pace, overcome my own problems, and not be disrupted by someone else’s needs…

If you had to prepare a man who hated running/exercise for the above, what would you tell him?

…I’d tell him very little of my experiences. I’d tell him to lubricate well, drink plenty, never use energy gels which are the consistency of sperm when nicely warmed in your running belt, wear leggings if you’re running along verges so the nettles don’t get you…

…choose the right socks…

…focus on the end goal and why you are doing what you are doing and be prepared to MTFU…

…think ‘I can’ not ‘I can’t’…

Do you believe that anyone can run long distances? If so, what quality do you think we possess as humans which allows us to do this?

…Yes. Mental determination above everything else…

…Yes. As the girl who never ran the cross country at school, or indeed ran for anything, I absolutely think that running is mind over matter. But that mind set is a killer. It’s the difference between doing 10 minutes and coming home or running for hours…

…Yes. If some people can then there’s no reason why others can’t – we are all made the same way…

…I think we have the physiology to do it but more importantly you have to want to do it. The body is really clever and changes and adapts but the mind needs a certain setting. Maybe those that are predisposed to be stubborn, determined, goal orientated etc are naturally more likely to take on the challenge than others…

…of course. All you need is the determination to do it and the ability will come. The biggest hurdle is realising that you CAN do things rather than always assuming that you can’t…

…regardless of what we’ve done to our bodies over the years, they are strong and they adapt quickly. The biggest hurdle we have is our minds which don’t adapt as fast. We need to believe we can do things and if we can achieve that we’ll quickly find actually DOING wasn’t the hard part…

Why do you run? And why do you run so far…?

…unlike gym bunnies or tennis partners – runners aren’t judgemental. Everyone is accepted, because every runner knows that one day you can run 10k in under an hour the next your like a beginner…

…because I can run and one day I won’t be able to…because lots of people can’t or won’t and I like that I can.

…because I can eat cake afterwards and not feel guilty…because it impresses my children…because sometimes they give you shiny medals…because my bum gets too wobbly if I don’t.

…when I am out, running, no one can get to me, or ask me to do anything, or to find anything, or to get them anything. I am just me.

…I began to run to get fitter and found I love it. I now run and run so far to push myself to my limits whatever they are…I enjoy the satisfaction of giving my everything and pushing myself as hard as I can…

…for me running is not just about fitness, it’s my time to get away from the phone ringing and emails coming through continuously. It’s my time to think and plan and get away from it all. Trying to think about things whether it’s work stuff or personal is a good way of switching off from what you are actually doing and those tired aching legs tend to be forgotten about for a while.

…I like the solitude – it gives me time to think…

…initially it was to improve my health, and to get away from my demons. Now I run to stretch what I can do, to strive for something bigger, better or just more crazy. And to get to the singular, relaxed state that I feel when I’m running a long way…

April 21, 2014

Fiction Unboxed

This week, Kickstarter welcomes a new project to its pages. Sean Platt, Johnny B. Truant and David Wright (who host the Self Publishing Podcast and wrote the excellent Write. Publish. Repeat.) will be asking us to fund a project called ‘Fiction Unboxed’. The goal? To produce a book in thirty days. They want to start with nothing – no plot, no character, not even a genre – and end the month with a completed book in their hands, polished, edited and bound with a professional cover. Not only that, but they want us to share in the experience. The Kickstarter rewards will include participation levels that allow project funders to watch the process live, witnessing every email and conversation along the way.

This week, Kickstarter welcomes a new project to its pages. Sean Platt, Johnny B. Truant and David Wright (who host the Self Publishing Podcast and wrote the excellent Write. Publish. Repeat.) will be asking us to fund a project called ‘Fiction Unboxed’. The goal? To produce a book in thirty days. They want to start with nothing – no plot, no character, not even a genre – and end the month with a completed book in their hands, polished, edited and bound with a professional cover. Not only that, but they want us to share in the experience. The Kickstarter rewards will include participation levels that allow project funders to watch the process live, witnessing every email and conversation along the way.

I can imagine how this will go down with some writers. They’ll probably think that they’re trying to prove that writing is easy, which it isn’t. A year or two back I probably would have baulked at this kind of project myself. I would have said that you couldn’t write anything of any worth in this time, that quantity cannot replace quality, that art cannot be forced. I even wrote something along these lines in a post about NanoWrimo.

Would I have been wrong to spout these long-held and unchecked sensibilities? I think so. I think so because, since that time, I’ve watched my daughter becoming interested in two things: drawing and stories.

In her four years on the planet my daughter has probably produced more pictures than Picasso on crack. Forests have died for her art. Blank paper offends her, and when all the paper in the house has been covered with ink and wax, which it usually is, she’ll move onto another medium – my skin is currently very en vogue.

I love watching her draw. She doesn’t get hung up on anything – she doesn’t pause to think, or to plan, or to bite her nails, or to stare at the page and wonder what the fuck she’s doing with her life and whether anyone will ever look at her drawing and why she ever thought she could draw this thing in the first place…she just draws. Because it’s fun to draw.

And then she shows it to me and I pay her with honest praise, because it’s always the best thing I’ve ever seen in my life. (I know this makes me sound sappy but it’s not my fault – somewhere along the line evolution decided that we find genius in our offspring’s shitty art.)

Then she starts drawing again.

She draws. She publishes. She repeats.

And she therefore assumes, understandably, that the same approach should be taken with the creation of stories. One day she discovered that the stories in her books didn’t just arrive there by magic – that they were written by other human beings and that, at one stage, they were just ideas in those human beings’ brains and that, if this was so, why couldn’t my brain give her all the other stories to save on buying all these books? Ever since then, I’ve been required, at least once every day and at the drop of the hat, to make up a story. There is no time to think; it has to be now. Now, now, faster, faster, now. And there has to be a unicorn in it and a bit where (every time, weirdly enough) a smaller animal gets hurt. Sometimes there must be zebras. Always there must be unicorns.

If you’ve tossed aside your career to become a writer, then you can’t say no to your child’s request for a made-up story, so I capitulate. It was hard at first and my first efforts were terrible - plot holes everywhere, unicorns backed into embarrassing situational corners from which they couldn’t escape. zebras talking to dull frogs for no reason. My zebras really were awful. But I soon realised that it was just the idea I found hard – then I got better at it, then the zebras got better, and then it became fun. This is pretty much true of all writing. It’s the prospect of the work that’s daunting; once you let go, the work takes care of itself.

Sean, Johnny and Dave aren’t trying to prove that writing is easy. I think they’re trying to say that writing is just a process like any other, and that the things that get in the way of that process are generally the beliefs and neuroses that writers battle with every day – the need to second-guess what our brains are producing, to question our own abilities and flinch from actually getting words onto the paper, whatever those words might be.

I’m really excited to see how this project pans out, so I’ll be there on day one to fund it. My guess is that they’ll do it – they’ll produce a good story in thirty days that’s good enough to sell. What I’m really interested to see is if they can produce something that not only entertains, but which resonates – my mark of a truly good book. I really hope they manage it.

What do you think? Would you like to read a book that’s only taken a month to write? Does crack really make you paint faster? Please share your thoughts, I’d be delighted to hear them.

January 20, 2014

Calling All Runners!

Why am I doing this again?

I want to hear about your experiences running long distances. Can you help?

Last year I began writing my second novel. It’s a post-apocalyptic story called The End of the World Running Club, about an under-achieving slob who finds himself having to run the length of a pretty messed-up United Kingdom to find his family.

I love running (the main character hates it) and I’ve been fascinated by ultra-running since reading books like Born to Run by Christopher McDougall and Eat and Run by Scott Jurek. I’m fascinated by the kind of will required to push the body through those 30, 50 and 100 mile slogs and by the physical, emotional and sometimes spiritual effects those distances can bring. I’ve personally never run further than a marathon, so to research what it’s like to run much longer distances (albeit not ones that include plane-wrecks, floods or asteroid craters) I contacted a few ultra-running friends of mine to see if they could help. Their responses were really useful and I thought it would be interesting to open up the same questions to a wider group.

Are you interested? Do you want the chance to wax lyrical about your own experiences (runners love doing this) and help shape a novel? You don’t necessarily have to have run an ultra; even if you’re a middle or short distance runner, I’d be interested to hear about your own experiences.

If you’d like to help, feel free to post your answers to the following questions in the Comments section below. Alternatively, you can just email your answers to me at adrian@adrianjwalker.com. I’m hoping to compile a list of the most interesting responses in the run up to the book’s release. This should be happen within the next few months -you can sign up for updates by entering your email address in the box to the right.

To say thanks, I’ll make sure every one who helps out receives a free copy of the eBook! I hope I regret saying that…

Here are those questions:

Can you give an account of the longest distance you’ve ever run in a single session and/or over consecutive days? What physical and psychological effects did you experience?

How does your mental/emotional state change over long distance? I’m interested to know what happens to your thought processes and feelings when you push yourself out of your comfort zone.

What state of mind do you find to be the most conducive to running extreme distances? Can you control this?

Have you ever hallucinated whilst running?

If so, did the hallucination help or hinder you?

Have you ever ‘blacked out’ whilst running, ie realised you’ve just run five or ten miles without realising it?

Have you ever broken through multiple walls whilst running a long distance? What gets you through them?

If you were facing a month of running a marathon or more every day, what would you see as the single biggest obstacle? How would you counter this?

Do you run better on your own or in company?

If you had to prepare a man who hated running/exercise for the above, what would you tell him?

Do you believe that anyone can run long distances? If so, what quality do you think we possess as humans which allows us to do this?

Why do you run? And why do you run so far…?

Thanks for your help!

January 11, 2014

It’s Like…

The Moon, yesterday.

My kids and I have a game we play in the car sometimes. I play them a piece of music and then we all take it in turns to say what it sounds like. It passes the time, they have fun and I get to secretly brainwash them with my musical taste which, as everyone knows, is one of the many joys of being a father.

The other day, I played them Singapore by Tom Waits. A while back, I tweeted that I thought Tom Waits’ voice sounded like an antique desk being thrown out of a steam train. I was trying to be clever, showing off, trying to get people to like me. I don’t think anyone retweeted it.

You know what my son said Singapore by Tom Waits sounds like? He’s two by the way.

An elephant.

Of course it does, that’s exactly what it sounds like. Not a desk.

I barely had time to register this piece of genius when the track ended and Three Hours by Nick Drake came on. As I started thinking about a suitable simile for Drake’s unique and vulnerable lilt, my son floored me again.

“The moon, Daddy. He sounds like the moon.”

Gulp.

My daughter then went on to say that The Pogues’ seminal album If I Should Fall From Grace With God… is “pirate music” and that one track in particular – Metropolis – sounds like a monkey going shopping. Which it does. It really does.

Bloody brilliant, my kids.

I’m currently completing rewrites of my second novel, a post-apocalyptic story called The End of the World Running Club. It’s a very enjoyable task, like ‘word mining’, and part of the process is to make sure I’m describing things correctly. I’ve been thinking a lot about how strange this process is – of trying to get people to imagine what I’m imagining using a long string of words. Stephen King calls it telepathy in his brilliant book On Writing. I think it’s more like resonance. The drama of a thunderstorm or the desolation of a burned forest already exists in everyone’s head. The job is not to describe it, but to trigger it. The job is to resonate – the deeper the simile, the stronger the resonance. If you use similes that are too precise, too close to the actual thing, you create a dull image. If you try to be too clever, call Tom Waits a desk, and people stop reading.

But go deep, trust the reader’s imagination, call Nick Drake the moon, and the image ignites. The fuel already exists in the reader’s head. All you have to do is make the sparks.

I suppose I was trying to do this with my Tom Waits tweet. He writes about things that are strange, sad and mechanical, so a broken old desk and a locomotive fit quite well. I also think that Year after Year by the band Idaho sounds like heavily sedated monks playing guitars outside in a thunderstorm, and that And Justice for All by Metallica sounds like a half-naked tramp coming at you with a cricket bat. But neither of those are as good as elephant or moon.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I have to find some way of shoehorning Nick Drake into a post-apocalyptic running fable.

January 7, 2014

The Colour You

The Colour You

My wife had to do one of those psychological tests at work. They’re suppose to tell you what kind of person you are and how people should behave around you. This one revealed her ‘colours’. The questions she answered were fed into a computer and the results told her what combination of the following colours her personality matched.

* Red

* Green

* Blue

* Yellow

(I should add that everyone in her company had to do it, not just her…she’s not been flagged.)

Corporations do these test so that their staff have a better understanding of what makes their colleagues tick, whether you’re interested in the details for example, or whether you just want a few key words, whether you just like to GET the JOB DONE (Gordon Ramsay hand slap), whether you’re a bright, positive person, or a touchy, feely caring one.

She arrived home believing she was some weird hybrid of Hitler and the dog from ‘Up’.

Can you guess what the colours above mean? Go on, have a go. Red, green, blue, yellow. You’re probably right. See they didn’t even try to avoid the obvious connotations.

I am RED. DANGER.

I am GREEN and I LOVE YOU.

I am YELLOW. I am happy! Ha ha!! What? SQUIRREL!

I am BLUE. Give me the details…OK that one doesn’t really work.

You can be a combination of two colours or, in rare cases (such as my wife’s) three. By my calculations, that means you can be one of ten different combinations. Even if there is some poor soul with all four colours running around the office babbling and shouting and crying and then suddenly flattening themselves against a corridor wall, and one blank-eyed, slack-jawed automaton with no colours at all dribbling and bumping into the water cooler all day, that still makes only twelve possibilities. The test, and therefore the corporation, believes that there are twelve different types of people walking its corridors. More to the point, it believes that its twelve types of people will perform better if they recognise their colleagues as one of those twelve different personalities and treat them differently because of this.

Twelve combinations. Twelve personalities. It’s the Corporate Zodiac.

I once made the mistake of responding to the question ‘What star sign are you?’. I should have just started screaming until the girl backed away, but instead I said ‘Gemini’, because unfortunately I knew.

She made this weird noise and gurned.

“Uh oh! Twins!”

Ha ha. You think there are just two of me? I could show you a thing or too. Go on, ask me who you’re speaking to now.

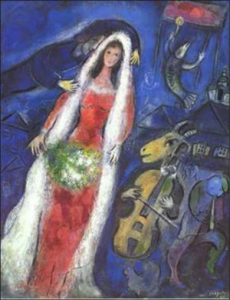

This is Marc Chagall’s La Mariee.

And this is it resized to 3×4 pixels.

Marc Chagall’s La Mariee is mostly blue.

I’m writing about five characters on a journey right now. I don’t know what their colours are. They’re complicated, I’m getting to know them, but I still can’t predict what they’re going to do next or how they’ll react to the next challenge. They’re complicated and they change all the time and they’re not even real people.

Real people are, at any given moment, unpredictable, confusing and confused.

Are you confused? I am. Most of the time, I am.

The people who write these tests and the corporations that inflict them upon their employees would argue that they are simply yardsticks; approximations of a character that give co-workers a head start when interacting with them. This might be true, but that’s not the end of the story. People like boxes and they don’t like surprises.

Example: at a team-building exercise after everyone had their colours explained to them, my wife’s group was split into sub-groups of their dominant colour. As the ‘Reds’ walked over to their table, they were booed by the rest. It was a joke of course, but jokes carry truth. In fact they’re one of the greatest sources of truth.

The other three teams had already made their minds up about the fourth team based upon a colour…I’m pretty sure we’ve seen this somewhere before.

OK, so it’s not as bad as racism, but it’s still a form of prejudice. Encouraging preconceptions about people is – I think we established some decades ago – naughty.

We are behavioural experimenters. Ask my son, he’s two. He is currently in the middle of an experiment right now. I’m trying not to take it personally and I’m fairly sure that when he’s twenty-one, he’s not going to be crying for his Mummy every time I tell him he can’t have chocolate on toast, or tell him it’s the middle of the night, or walk in the room, or look at him, or breathe. Because we’re not going to allow him.

Maybe all of our behaviour is like this. It’s only there because it’s been encouraged. Or discouraged.

Most people would agree that we’re not dropped onto planets or into offices fully formed. We’re each of us genetic experiments, concoctions poured through different sieves of circumstance. We are walking contradictions. We are subject to change – day by day, year on year, every second until the big one.

The test my wife did encourages people to encourage others to behave in the ways they’ve been encouraged to believe they already behave in, rather than just getting to know them. Trying to understand them.

You never will understand someone – not fully – but you can come close to it. When you do, the colours smear and wash away and you see the person underneath is not something binary but a combination of every experience they’ve ever had, every moment that’s scarred or inspired them, every monster that used to live under their beds, every dream they wake sweating from and won’t share with anyone, every joke that makes them laugh but falls flat to everyone else, everything they’ve ever touched or hurt or loved or hated. There are no colours for that, no card you can put on your desk. If you knew about all that stuff, if you really felt every moment of a person’s life, you wouldn’t call them a colour.

A few days after we found out that my wife was pregnant with our second child, we were riding our bikes into work together. We turned a corner and I watched her pedal past me, her face flushed, grinning, her legs pumping, her eyes shining, alive. Everything about her was positive. A great big grinning howl of life seemed to be pouring out of her. She was fully alive and creating life and I fell in love with her all over again. I rode behind her – because I enjoy riding behind her – but also because I wanted to watch her in that moment. I wanted to feel that howl for as long as I could.

That moment, the howl, coloured me, and the colour of that howl will always stay with me. I can’t tell you what that colour is. You’ll have to get to know me to find out.

Here’s another thing. In the report that my wife took home with her, there was a whole section dedicated to her ‘opposite’. It described their colours and how they thought, how to talk to them, how to deal with them. We read through the description and decided that, had I taken the test, I would probably pixelate into this category. I was her opposite.

Opposites attract. This is a good thing, isn’t it?

Not in this world. Nowhere in the instruction manual did it say how you would complement each other. How, with a bit of time and effort, with a bit of love, you could end up being the best team on the planet, not the cause of awkward friction in the work place.

Question: corporations are legally treated as individuals. What colour a corporation would be?

Answer: deepest black with an impregnable, chameleonic skin stretched across its gaping maw.

It’s fair to say that I don’t get on very well in those environments. Hearing about this test gave me yet another reason to be glad I no longer work in them, and to be grateful to my Nazi, squirrel-loving wife for taking on that burden so I can follow a more suitable path.

“I wish I wasn’t such a bad person,” my wife sighed as I dropped her at work the next day. I told her that bad people don’t wish they weren’t bad people. Then I told her she was every colour in the rainbow to me. She visibly winced, fought down the vomit, kissed me and walked through the revolving doors and into the fluorescent, air-conditioned, steel and glass humming building in which she fights daily to get herself heard above the noise of a thousand colour-book clones.

Don’t feel too sorry for her, she loves all that corporate crap. Her colours say so.

PS – here’s a picture of Doug as Hitler.

December 24, 2013

In a Dark and Troubled Place

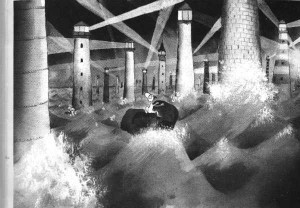

© Michael Leunig

A few weeks back, a friend sent me an email with a video about how the John Lewis ‘Hare and Bear’ Christmas advert was made. He said I might like it because it was amazing how they animated the animals, but then again I might not because I was probably the kind of person who don’t like Christmas adverts.

I thought about this and decided that he was right: I don’t like Christmas adverts. I don’t like most adverts, unless they make me laugh, in which case I’ve forgotten what I’m being sold and can get on with my life.

And no, I don’t like the Hare and Bear advert either. For anyone who hasn’t seen it, it’s a cutesy animation about a hare and a bear in a forest. The bear doesn’t understand Christmas (he’s a bear) so the hare tries to show him its meaning. The meaning, in this case, is a big, sparkly tree surrounded by lots of crap the bear doesn’t need. I don’t like the message: “Show someone the meaning of Christmas (by buying our stuff) – or – “If you don’t buy our stuff then you hate Christmas and you’re nothing more than a stupid fat bear.”

What I really don’t like is the fact that the bear is quite happy before the hare tries to save him from his empty, joyless life. He doesn’t need saving, he’s just a bear, being all beary, lollopping about, yawning, sleeping, scratching his arse and, almost certainly shitting in the woods. But what I really don’t like is the look on his face when he finally has his moment of ‘enlightenment’. He sees the tree and his pupils seem to dilate. He looks even more like a beast than he did before: hypnotised, feral, assimilated.

And then the hare gives this patronising ‘aaah’ look as the un-bear blunders down towards the tree like a moth to the flame. I find it unsettling.

Then I thought about it a bit more and realised that what I really didn’t like was my reaction to these kind of things. Complaining about the traditions of Christmas seems to have become one of those traditions. (Too much food, too much drink, too much family, too much stuff, too much advertising. Too much complaining. I’m complaining vaguely about something I’m actively engaging in, and therefore I’m letting the marketeers win. And I’m forgetting what this time of year really used to mean for me.

Some memories of Christmas:

Being 3, looking up at my Dad as he pretended to be Santa Claus by turning his red-lined work coat inside out. I thought he was better than Santa Claus and I hoped he would pick me up. And he did. He picked me up with one hand and smoked his Christmas cigar in the other. He smelled grown up. I think he had probably had a couple – I don’t blame him, we were living next to a graveyard in a house with no roof.

Watching my Dad sing carols in the church choir, then coming home to find the dog looking sheepishly up at us, having just eaten our Christmas presents, hoping we weren’t mad at her. We weren’t, she was too daft to get mad at.

A few years later, watching Star Wars for the first time. Then the Empire Strikes Back, then Return of the Jedi. Buying into the idea that even the most evil man in the universe can come good in the end, that there is hope even for him.

Being in the nativity play at school. My mum directed it and my Dad wrote it. It was set in space, on board an alien spaceship that turns out to be the star of Bethlehem. The spaceship has broken down, so the aliens watch everything going on down below and then leave the planet, pondering on hope and the fate of mankind. It was kind of edgy for a Primary school nativity, I’m surprised it made it to the stage.

I’m not religious. My beliefs change so often that it makes no sense to call them that any more. I have ideas, I suppose, and sometimes they stick around. I’m fairly sure that describes what happens for most people. But I do like the story of the nativity. Ignore the details, just look at the image: even in the coldest, loneliest, shittiest place, even in such a dark and troubled place, something hopeful can be born.

It’s hard being human. Most of the time we don’t know what we’re doing. Those moments when you think you’re in control are as fleeting as happiness itself. That’s why it’s important not to panic. To remember that things will probably work out for the best. To have hope, and most importantly, not to abandon it, because if you do, then you’re no better than the people who use it to try and sell you something: whether that’s an ideology or an aftershave. That’s why we remind ourselves, that’s why we tell stories. That’s why we have things like Christmas.

We see a billion things every day that remind us it’s easy to forecast doom. Not so to implore hope. Happy Christmas.