Larry Benjamin's Blog: Larry Benjamin's blog - This Writer's Life, page 2

June 7, 2018

A Fatherless Father's Day

I remember the accident as if it was yesterday.

I had been living in Washington, D.C. for three years. That particular morning, a Saturday, I was running late for work. It was a gray, wet morning at the edge of Winter. Heavy rain, like molten white gold, fell from an aluminum sky as I blazed along at 80 mph. A gray car merged onto the roadway from the right, then proceeded to move into my lane without signaling. The car was moving so slowly it looked like it was moving backwards. I pressed the brakes hard, pumping steadily with increasing pressure, my right hand tight on the gearshift ready to down shift. Realizing collision was inevitable, I glanced at the speedometer: 60. The impact sent my little car spinning towards the concrete divider separating west-bound traffic from east. The world seemed upside down. I remember thinking, I’m going to die and I never got to be friends with my father. I glanced up at the sky, oddly unafraid, and I swear I saw the hand of God reach down and stop my car from spinning.

Fast forward a few months: Father’s Day, 1988. I moved back to Philadelphia, in large part to be closer to my parents who lived in the Bronx. What I had thought would be my last thought haunted me. By being physically closer, I hoped to befriend my father. I don’t know if the thought of losing me, shook my father as much as I had been shaken, but I know after I got back to Philly, I started walking his way and he started walking mine. Sometimes we walked in rain, sometimes we walked with the sun on our backs. We gained a lot of ground because we both gave a little and learned along the way that no road is too long when you meet in the middle. When he died 29 years later, I lost not just my father, but my friend.

My older brother told me a story about Dad kissing him after commencement when he graduated from Syracuse University. Dad had, of course kissed us before, when we were younger, but for some reason that kiss stood out in his memory because it recalled dad’s pride and happiness, two things he didn’t demonstrate often.

I don’t recall Daddy ever saying he was proud of me—of any of us. He wouldn’t have done that any more than he would have said he was ashamed of us. But his pride was unmistakable. One day at the hospital, he introduced me to one of his nurses. “This is my son. He lives in Philadelphia,” he said, “He’s a writer.”

When my brother and I were cleaning out Daddy’s things, we found an old wallet filled with our class pictures from first grade to seventh grade; year after year, he’d add the new picture in from of the old one. Going through his wallet was like watching my brothers and I grow up in time-lapse photography. His father’s pride in his children was almost palpable. In an envelope, I found a series of Father’s Day cards I had sent him over years; each one was signed by me and Stanley, who daddy unflinchingly embraced as his son-in-law from the very beginning. That he kept those cards told me he was proud that I’d met a man he approved of and built the kind of life he wanted for me and each of my brothers.

My brother told me he remembers Dad’s graduation kiss every time he kisses his own son, Max. Max, my parents’ only grandchild.

Daddy always wanted grandchildren. When my older brother and his wife announced they were expecting a baby, daddy’s joy was unmistakable. He’d waited so long and yet he never once, as far as I knew, voiced his desire for a grandchild to my brothers. He’d only mentioned it to me once, many years ago.

Daddy started noticeably declining about a year before he died. After an accident, he was no longer allowed to drive. So, he used Uber to get to doctor’s appointments, my younger brother drove him to the bank and the barber shop. Dad would occasionally walk around their neighborhood on errands. The last time Dad went out by himself, was a December day. Returning home, he fell in the street and was taken by ambulance to the hospital. We were puzzled about where he’d been coming from. My brother discovered the answer a few days later when a Christmas card from our father, addressed to Max, arrived. In it was $300 in cash; the card was signed “Love, Grampy.”

Earlier this year, my brother, Max’s father told me he and his wife were expecting a second child. My first thought was oh man Daddy would have loved that. I did a quick calculation in my head and realized this new baby had been conceived while Daddy was dying; as one life was winding down, another was beginning.

We buried Daddy on November 15, 2017. As we drove away from the cemetery, I thought I am a fatherless man. Now, six plus months later, as Father’s Day approaches—our first without our Dad—I know I will never be fatherless, for daddy will always be with me, in the lessons he taught me, in the love he gave me so unconditionally, in my brother’s gentle kiss on his son’s cheek. Because of his influence, we, my brothers, and I will be the stand in for the father himself. I know that I will never be the man Daddy was, but I can aspire to be. In that effort, he remains my inspiration, my father.

My only remaining question is, who will be proud of me now?

Published on June 07, 2018 18:29

•

Tags:

father-s-day, fathers-and-sons, larry-benjamin

May 23, 2018

Peeing With the Girls: A Bathroom Saga

The mystery surrounding bathrooms have always been, well, a mystery to me.

When we were kids, our mother had a friend who had a daughter who was around the same age as my younger brother and me. When they came over, the three of us kids would head off to our bedroom to play. One day in the middle of playing my brother said he had to go to the bathroom, so Michelle and I went with him. He sat on the toilet and Michelle and I perched on the edge of the tub. Vernon cracked a joke and Michelle leapt to her feet and laughing nudged his shoulder—a bit too hard. My brother who was, at the time, extremely thin, fell bottom down into the toilet. Unable to free him, we called for our mothers. Once they had extricated him, Michelle’s mother looked at Michelle and asked her what she had been doing in the bathroom anyway.

“We were playing,” I explained reasonably, “and Vernon had to go to the bathroom, so we came with him.” I remember Michelle’s mother repeating she shouldn’t have been in the bathroom with us before abruptly leaving our apartment.

When I started grade school, I was struck by the stridency with which each teacher would explain boys went to the Boys Bathroom and girls went to the Girls Bathroom. It was never explained to me why this had to be though. Nor did anyone ever explain the difference between the two bathrooms. Finally, by fifth grade I’d had enough; curiosity was, if not killing me, then at least consuming an inordinate amount of my imaginings. Mr. Fassler was our teacher. One day each week, we would have lunch in our classroom instead of the big lunchroom downstairs. He’d play guitar and we’d all sing along. That was when opportunity presented itself, at last. I borrowed the bathroom pass—a rugged piece of wood that looked as if it had bene hewn from its mother tree by the sharp teeth of Paul Bunyan—and went down the hall. Making sure all the classrooms and halls were empty, I bypassed the Boys Bathroom and slipped into the Girls Bathroom. And was disappointed; aside from the abundance of pink tiles (the boys room was sheathed in blue), and absence of urinals, it looked exactly the same as the Boys Bathroom. I was nearly crushed by the disappointment.

A couple of years ago I walked into the men’s room at work and two guys were in there having a loud argument. There were three urinals and one guy was using the middle one. The other guy was yelling at him because now he couldn’t pee because, “you have to leave a urinal between you and the other guy,” he explained, vexed, “Everyone knows that!” By standing in the middle he’d made it impossible for the other guy to pee and he looked like he was about to wet his pants. I was afraid to add to the confusion by using one of the other available urinals, so I just slipped into a stall.

As a gay man who was quite frequently the only one, or at least the only one who was out at most of my jobs, peeing became an issue. Straight guys for the most part made standing at a urinal extremely tense. Maybe it was me; maybe it was them. It was uncomfortable for all of us. I usually just found a bathroom on another floor. I had one friend, a straight guy I’ll call P. He had more pee issues than I did. He would wait until his eyeballs were practically about to float out of his head before going to the bathroom. Inevitably as he was about to relieve himself, someone would walk in to use an adjacent urinal. Then he would lose his ability to pee. He took pee shy to a whole other level. We often met in the same bathroom two floors and a wing away from our office space.

I now work for an LGBTQ nonprofit. We have 18 single occupancy gender neutral bathrooms. After my first day at work, I texted P a photo of our bathroom sign. “I’m in heaven,” I crowed.

At least I was in heaven until our annual gala last week. The only thing worse than trying to pee in a men’s room full of straight guys is trying to pee in a room full of A-list queens and pretenders to the throne. I found the one gender-neutral bathroom and stumbled in. There was a woman adjusting her makeup in the mirror and another one waiting outside the stall. They both greeted me cheerfully. I went to the urinal and we started to have a conversation. A woman peeing in the next stall called out, “Larry is that you?” It turned out to be one of my coworkers. When she finished she came out and gloated because she had peed faster than I. A woman complimented my evening jacket. We talked clothes as I washed my hands.

Later, I returned because I had to change clothes. “Hey,” I said to the two women who were in there, “I have to get out of these pants, do you mind?”

“No, “they said, “go right ahead.” As I hopped about in my underwear, we started chatting about the event. Dressed, I bid them goodnight and left, thinking that had been the best, most fun bathroom experience of my life. And it brought me back to my original childish question—why do boys and girls have to use separate bathrooms?

Published on May 23, 2018 16:37

•

Tags:

bathrooms, larry-benjamin

May 6, 2018

On Grief: A Son Copes with his Father’s Death

Recently my brothers and I attended a veteran's memorial service at the James J. Peters VA Medical Center (Bronx, NY). In a way it was like telling our dad goodbye again, but in another way we found a community. I wrote an article about the experience for Philadelphia Gay News that explores not just the day and my feelings but grief in general. Hope you'll give it a read.

Published on May 06, 2018 08:28

•

Tags:

bronx, fathers-and-sons, grief, larry-benjamin, pgn, philadelphia-gay-news, veteran, veterans

March 27, 2018

Toby & Larry: An Unconditional Love Story

Even now, after all is said and done, after thirteen years together, after he is gone, I find it hard to explain Toby and me.

December 10, 2005. Princeton, New Jersey: The first time ever I saw his face.

There was snow on the ground. The air was frigid and dense with the hope of finding “the one,” and at the same time like a vacuum of held breath. Above the chaos, a leaden sky sagged, gray and heavy with inarticulate hope.

“Is that Toby?” I asked a woman walking by. “It is,” she said. He was as handsome as he was in his pictures online; I leaned down, breathless, and he, unexpectedly, jumped into my arms, landing on my chest. Our hearts collided, seemed to stop for a moment and continued to beat in synchrony; his next exhaled breath matched mine exactly. The next breath, drawn in surprise, also in synch.

We were Toby’s fourth home in less than two years. I spoke to his original owner once, just briefly. He explained that Toby had behavioral problems, which had prompted him to give Toby up for adoption. Their vet he added had “suggested neutering Toby would fix the problem, but I couldn’t do that—I just couldn’t do that to him,” he said. So, he gave him up for adoption. I have held that first owner in contempt from the moment those words fell from his lips.

Toby.

Toby accepted me as I was. My whole life, I’ve struggled with not being enough: I was never smart enough, or butch enough, or good-looking enough. For Toby, I was not only enough—I was everything. Perhaps that is what makes dogs so special to us; we are always enough and everything.

Once in the park, a stranger admired Toby’s good looks, “Tell me,” he said, “Is he a good dog?”

“He,” I responded, “Is the best dog he knows how to be.”

The stranger thought for a moment, nodded his head, and responded, “I like that. I really like that.”

March 20, 2018. Mathew J. Ryan Veterinary Hospital: The last time ever I saw his face.

Another winter day. The sky hung low, white with anger. From the flattened arc of the heavens, snow tumbled down, like dashed hope. Accumulating on the ground in piles and drifts, it lay there like an old mattress, too lumpy and itchy to offer comfort to the weary.

Toby licked my nose, then settled against me.

“He’s gone,” the vet said, moving the stethoscope from his chest.

Gone?

I looked down at Toby cradled in my arms, tight against me, his chest rising and falling in synch with mine. “Gone? But he’s still—”

“I thought that at first, too,” she said,” But, it’s your breathing that makes it look like he is…”

I nodded. I kissed the top of his head one last time, and gently surrendered him to her.

And now, now, I keep looking around for him, even as I stare at the stack of vet bills on my desk amounting to many thousands of dollars, and realize, I would have generated many thousands more if it would have bought me more time with him.

I seek refuge in the knowledge that I did my best for him, that it was his time to leave, that he was ready. I lean into my trust that he would not have left me if he wasn’t sure I was ready to let him go.

December 10, 2005. Princeton, New Jersey: The first time ever I saw his face.

There was snow on the ground. The air was frigid and dense with the hope of finding “the one,” and at the same time like a vacuum of held breath. Above the chaos, a leaden sky sagged, gray and heavy with inarticulate hope.

“Is that Toby?” I asked a woman walking by. “It is,” she said. He was as handsome as he was in his pictures online; I leaned down, breathless, and he, unexpectedly, jumped into my arms, landing on my chest. Our hearts collided, seemed to stop for a moment and continued to beat in synchrony; his next exhaled breath matched mine exactly. The next breath, drawn in surprise, also in synch.

We were Toby’s fourth home in less than two years. I spoke to his original owner once, just briefly. He explained that Toby had behavioral problems, which had prompted him to give Toby up for adoption. Their vet he added had “suggested neutering Toby would fix the problem, but I couldn’t do that—I just couldn’t do that to him,” he said. So, he gave him up for adoption. I have held that first owner in contempt from the moment those words fell from his lips.

Toby.

Toby accepted me as I was. My whole life, I’ve struggled with not being enough: I was never smart enough, or butch enough, or good-looking enough. For Toby, I was not only enough—I was everything. Perhaps that is what makes dogs so special to us; we are always enough and everything.

Once in the park, a stranger admired Toby’s good looks, “Tell me,” he said, “Is he a good dog?”

“He,” I responded, “Is the best dog he knows how to be.”

The stranger thought for a moment, nodded his head, and responded, “I like that. I really like that.”

March 20, 2018. Mathew J. Ryan Veterinary Hospital: The last time ever I saw his face.

Another winter day. The sky hung low, white with anger. From the flattened arc of the heavens, snow tumbled down, like dashed hope. Accumulating on the ground in piles and drifts, it lay there like an old mattress, too lumpy and itchy to offer comfort to the weary.

Toby licked my nose, then settled against me.

“He’s gone,” the vet said, moving the stethoscope from his chest.

Gone?

I looked down at Toby cradled in my arms, tight against me, his chest rising and falling in synch with mine. “Gone? But he’s still—”

“I thought that at first, too,” she said,” But, it’s your breathing that makes it look like he is…”

I nodded. I kissed the top of his head one last time, and gently surrendered him to her.

And now, now, I keep looking around for him, even as I stare at the stack of vet bills on my desk amounting to many thousands of dollars, and realize, I would have generated many thousands more if it would have bought me more time with him.

I seek refuge in the knowledge that I did my best for him, that it was his time to leave, that he was ready. I lean into my trust that he would not have left me if he wasn’t sure I was ready to let him go.

Published on March 27, 2018 19:27

•

Tags:

dogs, grief, larry-benjamin, toby

February 18, 2018

Ode to Words (Part 3): Silence

My father taught me the value of silence. It was from him that I learned it takes more strength to hold your tongue than to loose it. Daddy was always the quiet one in our house. My mother’s voice was the dominant, reasoning soundtrack. My brothers’ voices were like murmurs on the wind .I was the noisy, unruly, talkative one. I was “like a clapper bell from hell,” my quiet father insisted.

I spent my adolescence resenting my father’s silence, my twenties and thirties trying to understand it, only to discover in my forties that daddy wasn’t intentionally silent: he only spoke the words that needed to be spoken. By the time I entered my 50s, he ended nearly every phone call with “I love you.” He used his words sparingly, saying only what needed to be said. If he told me over and over that he loved me it was because he knew I needed to hear he loved me.

For me, noisy kid that I was, my father’s silence was particularly jarring when set against my mother’s loquaciousness. Her words like foot soldiers ran onto the battlefield only to trip on the cliff edge and tumble into the abyss of his silence—at least that’s how it seemed to me in my fevered writer’s imagination: an endless, tireless army of words tumbling into the abyss of silence.

If you’ve read any of my early work, you may have noticed that one of my recurring themes is “silence.’ This is hardly surprising given my stories are nearly all grounded in truth, in my lived experiences. A big part of that lived experience was the quietness of my father.

The excerpt below, from one of my short stories, “2 Rivers,” is one of my favorites, in part because it was inspired by my parents and how I saw them at the time:

EXCERPT

My mother was a professional florist; she orchestrated stunning arrangements in priceless porcelain vases for people with no sense of beauty or smell. She talked constantly, compulsively. To my father. To herself. To her minions of flowers. Her voice filled the empty rooms around her like sunshine after a rain. Her words tumbled over each other, reaching, grasping air, plunging hysterically into the void of my father’s silence. Her voice entertained him, seduced him, very rarely elicited his laughter, sometimes accused him.

My mother’s voice underscored my childhood memories like a Max Steiner score. It was, of course, her voice that welcomed me home, wafting down the stairs, “Luke, is that you?”

Her voice greeted me at the front door, embraced me, backed away holding me at arm’s length, then pulled me to her bosom and escorted me through the house. It was as if her loquaciousness could compensate for his resolute silence. Or did it perpetrate it? For even if he had been inclined to speak, he would not have been able to get a word in edgewise.

In that house, the scent of flowers suffocated me. Like my father’s silence. Like my mother’s voice. Her words, serfs that had once done my bidding—cajoling me out of a mood, entertaining me, comforting my distress—now rose up against me, their feudal lord. An army of words, taking up arms, striking down the nation of me.

I had to leave, had to get back to Seth, to make him understand. My mother’s voice escorted me to my car, hugged me one last time, wished me safe passage, urged my speedy return.

—From “2 Rivers,” Damaged Angels

Conceptually, I see writing creative fiction as a way to create art from found objects. Thus, everything around me, finds its way into my work as a found object; I don’t so much invent as retell, observe, and detail.

I’ll be at the AWP Writer’s Conference in Tampa, FL next month where I’ll be joining fellow authors Alan Lessik and Kathy Anderson on a panel discussing “Writing LGBTQ Fiction Based on Real People.” My father will almost certainly come up. I hope you can join us for the discussion.

WORKSHOP DESCRIPTION

Writing LGBTQ Fiction Based on Real People

Novels and short stories are often shaped by real events happening to real people that they know. Three LGBTQ writers will talk about the real people within their stories and how the creative process changed both the characters and ultimately the authors themselves. For LGBTQ writers, exploring these stories become an exploration of our larger community and the known and unknown histories of our lives. Each of our writers will discuss these themes and read from their works.

Workshop # F124

Room 11, Convention Center, First Floor

Friday, March 9, 2018

9:00 am -10:15 am

______________

I spent my adolescence resenting my father’s silence, my twenties and thirties trying to understand it, only to discover in my forties that daddy wasn’t intentionally silent: he only spoke the words that needed to be spoken. By the time I entered my 50s, he ended nearly every phone call with “I love you.” He used his words sparingly, saying only what needed to be said. If he told me over and over that he loved me it was because he knew I needed to hear he loved me.

For me, noisy kid that I was, my father’s silence was particularly jarring when set against my mother’s loquaciousness. Her words like foot soldiers ran onto the battlefield only to trip on the cliff edge and tumble into the abyss of his silence—at least that’s how it seemed to me in my fevered writer’s imagination: an endless, tireless army of words tumbling into the abyss of silence.

If you’ve read any of my early work, you may have noticed that one of my recurring themes is “silence.’ This is hardly surprising given my stories are nearly all grounded in truth, in my lived experiences. A big part of that lived experience was the quietness of my father.

The excerpt below, from one of my short stories, “2 Rivers,” is one of my favorites, in part because it was inspired by my parents and how I saw them at the time:

EXCERPT

My mother was a professional florist; she orchestrated stunning arrangements in priceless porcelain vases for people with no sense of beauty or smell. She talked constantly, compulsively. To my father. To herself. To her minions of flowers. Her voice filled the empty rooms around her like sunshine after a rain. Her words tumbled over each other, reaching, grasping air, plunging hysterically into the void of my father’s silence. Her voice entertained him, seduced him, very rarely elicited his laughter, sometimes accused him.

My mother’s voice underscored my childhood memories like a Max Steiner score. It was, of course, her voice that welcomed me home, wafting down the stairs, “Luke, is that you?”

Her voice greeted me at the front door, embraced me, backed away holding me at arm’s length, then pulled me to her bosom and escorted me through the house. It was as if her loquaciousness could compensate for his resolute silence. Or did it perpetrate it? For even if he had been inclined to speak, he would not have been able to get a word in edgewise.

In that house, the scent of flowers suffocated me. Like my father’s silence. Like my mother’s voice. Her words, serfs that had once done my bidding—cajoling me out of a mood, entertaining me, comforting my distress—now rose up against me, their feudal lord. An army of words, taking up arms, striking down the nation of me.

I had to leave, had to get back to Seth, to make him understand. My mother’s voice escorted me to my car, hugged me one last time, wished me safe passage, urged my speedy return.

—From “2 Rivers,” Damaged Angels

Conceptually, I see writing creative fiction as a way to create art from found objects. Thus, everything around me, finds its way into my work as a found object; I don’t so much invent as retell, observe, and detail.

I’ll be at the AWP Writer’s Conference in Tampa, FL next month where I’ll be joining fellow authors Alan Lessik and Kathy Anderson on a panel discussing “Writing LGBTQ Fiction Based on Real People.” My father will almost certainly come up. I hope you can join us for the discussion.

WORKSHOP DESCRIPTION

Writing LGBTQ Fiction Based on Real People

Novels and short stories are often shaped by real events happening to real people that they know. Three LGBTQ writers will talk about the real people within their stories and how the creative process changed both the characters and ultimately the authors themselves. For LGBTQ writers, exploring these stories become an exploration of our larger community and the known and unknown histories of our lives. Each of our writers will discuss these themes and read from their works.

Workshop # F124

Room 11, Convention Center, First Floor

Friday, March 9, 2018

9:00 am -10:15 am

______________

Published on February 18, 2018 11:21

•

Tags:

aalan-lessik, awp, kathy-anderson, larry-benjamin, writing

January 8, 2018

Moving On

I haven’t been able to write.

If you’re not a writer, that probably sounds melodramatic. If you’re a writer, you probably d understand how upsetting it is to write those words, to be unable to write.

Like a lot of writers, I would imagine, I sometimes go long stretches without writing, because I don’t have anything to say. This dry period feels different though. I want to write, know what I want to say but somehow the words aren’t coming. Work on my next book stalled after the first paragraph. I tried to be patient, gentle with myself, solicitous of my fragile talent. I’m just tired, I told myself. There’s been a lot going on, I reminded myself: our dad died, I started a new job, there were the holidays …

I dreamt of Daddy the other night. I was walking through a crowded train station, carrying a heavy box in my hands, close to my chest. I have no idea what was in the box, but it was heavy. Everything was in black and white; the hard, white light falling from the skylight above made everything gleam like metal. Then I saw him, walking in the crowd towards me. Everything was in black and white, except him. He was all sepia tones: brown suede jacket, khaki pants, sharply creased, highly shined brown shoes; his brown face and terra cotta lips shone. Dad. As he passed me without speaking, he smiled. As I continued walking in the opposite direction—I knew, somehow, I couldn’t turn around and follow him—I slowed my pace. I remembered when I first moved back to NY after college, I was working at Macys. Occasionally, I’d end up on the same train as my dad going home at the end of the day. He walked fast and always seemed to be ahead of me as he got off the train. Knowing I couldn’t yell out to him, I usually just trailed in his wake catching up to him in our building’s lobby as he waited for the elevator.

Though Dad’s smile had acknowledged me, his look had also warmed me, made it clear I couldn’t follow him, that I had to continue on my path as he continued on his. I started to walk faster and when I looked down at my hands, I realized they were empty, my heavy box gone.

When I woke up, I pondered the dream. Dad seemed to be telling me he had to go on his journey and I had to continue on mine. It was time to let him go. Oddly, I’d thought I had but maybe not. Maybe my own unacknowledged grief was what was holding me back, stealing my words.

That day, I made flight and hotel reservations for the 2018 AWP Conference & Bookfair where I will be joining fellow writers, Alan Lessik and Kathy Anderson, in presenting a workshop on Writing LGBTQ Fiction Based on Real People. I used some of the money Dad left me to pay for the trip. That night I was unable to sleep. I was effectively alone. Stanley, exhausted from the marriage of Prozac and Vodka, had plunged headlong into sleep an hour earlier, Riley curled at his side. Toby dogged my steps as I walked into the library and began to look for a book to read. I hadn’t read a book in I don’t know how long. It made sense that I hadn’t read. And not reading seemed related to my not writing. For, if I couldn’t lose myself in the words, the story of another, how could I lose myself in the story I needed to tell? I pulled Graham Green’s “Travels With My Aunt,” off a shelf and began to read. The first line was “I met my Aunt Augusta for the first time in more than half a century at my mother’s funeral.” My new book opens with a funeral so my pulling Green’s book off the shelf seemed more fortuitous than random.

After our dad died, our youngest brother Kenon, told us about the day mom and dad dropped him off at Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh his freshman year. Kenon became unsure as they were getting ready to leave him and head back to the Bronx. My father pulled him aside and told him, “If I didn’t think you could do this, I wouldn’t leave you here.”

Kenon had chosen his path and dad delivered him to the head of it. When he ‘d hesitated beginning his journey, dad had nudged him forward. Just as he seemed to be nudging me in my dream.

Dear D.:

I went for a walk today in the snow. As I stood waiting to cross the street, I looked up at the sky, the snow-covered roofs edging the snow-filled sky. I remembered standing on that same corner and looking up into a fall sky, the leaves on the trees red-orange-red, so that I had felt as if I had been staring into the heart of a fire. C. had been alive then, and I had felt warmed by his love, brilliant as that tree.

A childhood fancy captured me suddenly, and I lay down in the snow and, moving my arms and legs in a sweeping arc, made a “snow angel.” I tired quickly and lay still for a moment within that casket of snow and ice. A memory of C.—of C., naked and beautiful, holding a single yellow rose against his chest—reached up and tugged at my heart, pulling me to my feet, leading me away. I left grief behind, buried in a shallow grave.

I watched the snow fall. I watched a snowflake fall for each life that had been lost. I watched a snowflake fall for each tear that had been shed over a life that had been lost. I watched a king’s ransom in snowflakes, like diamonds and pearls, fall soundlessly to the ground.

Love,

S.

—Excerpt from “The Cross,” Damaged Angels

If you’re not a writer, that probably sounds melodramatic. If you’re a writer, you probably d understand how upsetting it is to write those words, to be unable to write.

Like a lot of writers, I would imagine, I sometimes go long stretches without writing, because I don’t have anything to say. This dry period feels different though. I want to write, know what I want to say but somehow the words aren’t coming. Work on my next book stalled after the first paragraph. I tried to be patient, gentle with myself, solicitous of my fragile talent. I’m just tired, I told myself. There’s been a lot going on, I reminded myself: our dad died, I started a new job, there were the holidays …

I dreamt of Daddy the other night. I was walking through a crowded train station, carrying a heavy box in my hands, close to my chest. I have no idea what was in the box, but it was heavy. Everything was in black and white; the hard, white light falling from the skylight above made everything gleam like metal. Then I saw him, walking in the crowd towards me. Everything was in black and white, except him. He was all sepia tones: brown suede jacket, khaki pants, sharply creased, highly shined brown shoes; his brown face and terra cotta lips shone. Dad. As he passed me without speaking, he smiled. As I continued walking in the opposite direction—I knew, somehow, I couldn’t turn around and follow him—I slowed my pace. I remembered when I first moved back to NY after college, I was working at Macys. Occasionally, I’d end up on the same train as my dad going home at the end of the day. He walked fast and always seemed to be ahead of me as he got off the train. Knowing I couldn’t yell out to him, I usually just trailed in his wake catching up to him in our building’s lobby as he waited for the elevator.

Though Dad’s smile had acknowledged me, his look had also warmed me, made it clear I couldn’t follow him, that I had to continue on my path as he continued on his. I started to walk faster and when I looked down at my hands, I realized they were empty, my heavy box gone.

When I woke up, I pondered the dream. Dad seemed to be telling me he had to go on his journey and I had to continue on mine. It was time to let him go. Oddly, I’d thought I had but maybe not. Maybe my own unacknowledged grief was what was holding me back, stealing my words.

That day, I made flight and hotel reservations for the 2018 AWP Conference & Bookfair where I will be joining fellow writers, Alan Lessik and Kathy Anderson, in presenting a workshop on Writing LGBTQ Fiction Based on Real People. I used some of the money Dad left me to pay for the trip. That night I was unable to sleep. I was effectively alone. Stanley, exhausted from the marriage of Prozac and Vodka, had plunged headlong into sleep an hour earlier, Riley curled at his side. Toby dogged my steps as I walked into the library and began to look for a book to read. I hadn’t read a book in I don’t know how long. It made sense that I hadn’t read. And not reading seemed related to my not writing. For, if I couldn’t lose myself in the words, the story of another, how could I lose myself in the story I needed to tell? I pulled Graham Green’s “Travels With My Aunt,” off a shelf and began to read. The first line was “I met my Aunt Augusta for the first time in more than half a century at my mother’s funeral.” My new book opens with a funeral so my pulling Green’s book off the shelf seemed more fortuitous than random.

After our dad died, our youngest brother Kenon, told us about the day mom and dad dropped him off at Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh his freshman year. Kenon became unsure as they were getting ready to leave him and head back to the Bronx. My father pulled him aside and told him, “If I didn’t think you could do this, I wouldn’t leave you here.”

Kenon had chosen his path and dad delivered him to the head of it. When he ‘d hesitated beginning his journey, dad had nudged him forward. Just as he seemed to be nudging me in my dream.

Dear D.:

I went for a walk today in the snow. As I stood waiting to cross the street, I looked up at the sky, the snow-covered roofs edging the snow-filled sky. I remembered standing on that same corner and looking up into a fall sky, the leaves on the trees red-orange-red, so that I had felt as if I had been staring into the heart of a fire. C. had been alive then, and I had felt warmed by his love, brilliant as that tree.

A childhood fancy captured me suddenly, and I lay down in the snow and, moving my arms and legs in a sweeping arc, made a “snow angel.” I tired quickly and lay still for a moment within that casket of snow and ice. A memory of C.—of C., naked and beautiful, holding a single yellow rose against his chest—reached up and tugged at my heart, pulling me to my feet, leading me away. I left grief behind, buried in a shallow grave.

I watched the snow fall. I watched a snowflake fall for each life that had been lost. I watched a snowflake fall for each tear that had been shed over a life that had been lost. I watched a king’s ransom in snowflakes, like diamonds and pearls, fall soundlessly to the ground.

Love,

S.

—Excerpt from “The Cross,” Damaged Angels

Published on January 08, 2018 18:15

•

Tags:

alan-lessik, awp, dad, grief, kathy-anderson, larry-benjamin, snow, writer-s-block, writing

December 22, 2017

In a Season of Excess

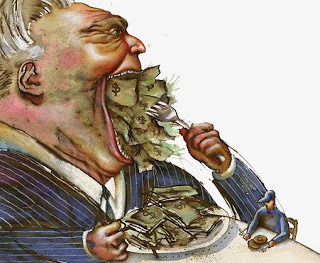

I am troubled by the times we are living in. We have a Trump-driven, GOP-supported tax “reform” bill that is nothing short of a massive transfer of wealth from the poor and middle-class, who comprise 99 percent of the U.S. population to the richest one percent. Over the weekend it was revealed Senator Bob Corker changed his “no” vote to a “yes,” after a tax break that would hand him a windfall of millions was snuck into the bill.

As I ponder the current climate, a season of excess, a world where greed is its own reward, and robbing the poor and middle class to enrich the already wealthy drapes the robbers in gilt-edged robes of glory, I am deeply disappointed. And afraid.

Sure we’ve seen this before, most recently in the Reagan area (who can forget Nancy Reagan wearing red and ordering 4,370 pieces of Lenox china (enough place settings of 19 pieces for 220 people) at a cost of more than $210,000? Who can forget the halcyon days of “Dynasty” and the Carringtons, and “Dallas” and JR Ewing (who did shoot JR?)—a period that gloried in excess: mansions and designers dresses mostly distinguished by over-sized and ridiculous shoulder pads that one could only assume were a reflection of the wearer’s outsized bank account and stock portfolio. Still, missing from that prolonged orgy of excess was the maliciousness, the sheer meanness that characterizes the current administration and its actions. Amassing more—and ensuring that more remains concentrated in as few hands as possible—has become the noble purpose of the current ruling political party.

Several events over the last year have caused me to re-examine my relationship to money, to things. First our aunt died in January, then our dad died in November. Money could not have saved either of them. When we first found out my dad was dying I asked him if there was anything he wanted. He said he just wanted to spend as much time with us, his family, as he could. Not a trip to Paris, not a Ferrari. Time. With us.

Then I left the for-profit sector after a horrific few years in corporate communications and switched to the non-profit sector, which pays considerably less well but which allows me to feel fulfilled in a way I never associated with work.

Last Saturday we had dinner with a friend we hadn’t seen in a while. She recently retired and was discussing life after work and her new awareness of money. She pointed out she had everything she needed but had to start thinking about what she bought and how she spent money. I could totally relate to that but then she mentioned a New York Times article she’d recently read about a woman who gave up shopping for a year. I was instantly intrigued. I don’t think of myself as a “shopper” but we have a lot of stuff, which I suppose is normal for two gay men of a certain age.

For example, we like cheese; we eat a lot of it. In fact, whenever we have people over for dinner, appetizers typically include a cheese plate. So I suppose in a way it is understandable that we have seven cheese knives, porcelain cheese labels, slate serving pieces that allow you to write a cheese descriptor in chalk. Still, we have seven cheese knives.

I like books, buy way too many of them…Seriously, we have more than 1,000: signed first editions, art books, leather bound books from The Easton Press, with gilt edged pages and satin ribbon markers, and numbered, limited editions with hand marbled endpapers from The Folio Society.

So, I was intrigued by the idea of not shopping. Our friend sent me the article, “My Year of No Shopping,” by Ann Patchett, Sunday morning and I read it with interest. In the article, Patchett explains:

"At the end of 2016, our country had swung in the direction of gold leaf, an ecstatic celebration of unfeeling billionaire-dom that kept me up at night. I couldn’t settle down to read or write, and in my anxiety I found myself mindlessly scrolling through two particular shopping websites, numbing my fears with pictures of shoes, clothes, purses and jewelry. I was trying to distract myself, but the distraction left me feeling worse, the way a late night in a bar smoking Winstons and drinking gin leaves you feeling worse. The unspoken question of shopping is 'What do I need?' What I needed was less."

I read her words and I thought—Yes, That’s it exactly: I need to buy less and give more. I need to share other capital—time, love, interest, resistance.

And that is exactly what I intend to do in 2018. Revisit this blog to track my progress. In the meantime, you can read Ann Patchett’s thought-provoking article here.

Published on December 22, 2017 17:51

•

Tags:

ann-patchett, bob-corker, gop, greed, larry-benjamin, nancy-reagan, tax-reform

November 8, 2017

Saying Goodbye to My Dad

Today at 10:31 a.m., my dad closed his eyes for the last time. When he did, a part of me died with him.

I’ll accept your condolences but please check your religion at the door. And don’t talk to me of your God and His wisdom and mercy. Not today. Not today. I believe in God, I do. But not today. Not today. Today, I feel He abandoned me and my father when all I could do was hold his hand and rub his head and tell him I loved him; when all his doctors could do was increase his pain medicine and escalate the frequency with which he received them, and swab his mouth with plain gelatin to make up for the water he could no longer drink, the food he could no longer eat.

The first time I, went, alone, to visit dad in the hospital, I arrived in his room while he was still downstairs in radiation. A nurse walked in and asked who I was.

“I’m Larry, his middle son.”

“Oh, you’re the one who lives in Philadelphia!”

“Yes, how did you know that?”

“Your dad talks about you. He talks about all of his sons.”

My dad talked about me. He owned me as his son. He owned me as I own myself, in my imperfection, in my boisterousness, in my rowdy affection, in my gayness. That meant the world to me.

I stayed at the hospital in his room on more than one occasion. One morning when they brought him his breakfast, I got up and added cream & sugar to his coffee and opened the packet containing knife and fork and napkin. Having done that, I speared a section of omelet and moved the fork to his mouth. “I can feed myself,” he said sharply. I handed him the fork and picked up my overnight bag. Dad would need help feeding himself. But not today. Not today.

As I walked away, he asked, “Are you going home?”

“No,” I called over my shoulder. “I’m going to shower and change. Holler if you need anything.”

A few weeks later, I got caught in traffic and missed having lunch with him. When I arrived he was eating ice cream. Judging by how melted it was, he’d been at the ice cream eating for a while. And he was wearing more ice cream that he could possibly have eaten. I watched him struggle to bring spoon to mouth but did not offer any assistance. When he finally, accidentally, upended the container of ice cream, I said, “You’re all finished,” and quietly cleaned up the mess he’d made.

Saturday as I was on my way to New York to visit, Dad’s doctor called to say Dad had begun his “transition,” and we’d better come at once. I called my brothers and getting on the New Jersey Turnpike, I settled in the left lane, and depressed the accelerator until the speedometer read “90.” I was the last to arrive at dad’s bedside. It was my younger brother’s birthday. Dad, unmoving, eyes closed, unable to speak, slept on peacefully, his breathing strong. Dad was dying. But not today. Not today.

My dad died today, four days after he began his “transition.” Instead of crying, I’m remembering all the conversations we had in that hospital room; I’m remembering what he told me about his funeral and that he assumed I’d write his obituary. Instead of crying, I’m focusing on the myriad things that need to happen now, on all the things that remain to be done. I know I’ll cry—Daddy deserves tears, and my bruised heart needs the release of tears.

Yes, I’ll cry. But, not today. Not today.

Published on November 08, 2017 17:59

•

Tags:

fathers-and-sons, grief, larry-benjamin

October 18, 2017

Rainbows & Unicorns, or Truth in Fiction

An author ought to write for the youth of his own generation, the critics of the next, and the schoolmaster of ever afterwards. — F. Scott Fitzgerald

I, like most writers with a modicum of self-control and a soupcon of good sense, don’t comment on reviews. But I do read each and every one. Mostly out of curiosity. I’m genuinely curious about what readers think of my work, of the stories I chose to tell, of the words I choose to tell them with—and yes, I realize that can be two very different things. I realize reviewers write not for writers but for other readers to either steer them to books they liked or away from others that somehow disappointed them.

I don’t read reviews to learn what readers want—I decided long ago when I started writing seriously that I wasn’t writing to market but rather writing the stories that burned in me and let the market find me. Perhaps a stupid approach—certainly not a lucrative one, but one that allows me to feel good about my work. And on those dark days, that all writers experience, when I doubt my talent and despondency threatens to consume me, I remind myself that The Great Gatsby—arguably one of the best books ever written—was, at the time it was published, a commercial failure.

Like I said, I read all my reviews and there are often common themes reflected in these. I’ve decided to address the most common themes in this post.

Timeline

While the timespan for all three off my novels vary from 10 to 40 years, all three encompass the period from the late 70s to the late 80s. Quite simply that is because that is when I came of age. I write not so much to remember as to ensure we don’t forget. I write to honor those no longer here. I write to tell their stories, to keep them present. As Lincoln says in Unbroken: “And in between all the faces that were present, all the faces that weren’t; I saw Maritza smile and Thibodeaux nod.”

All three books explore similar themes. The explanation for that is simple. I saw these three books as a sort of triptych. They are “stand-alone” novels but taken together they are a like a series of painting exploring the same subject. Somewhere in my mind there is an idea to bring the characters from all three books all together in a fourth book.

Bad things/Dark things

Sure, bad things—sometimes terrible things--happen to my characters. But with the bad there is good—just as in real life. And as in life, every night is followed by a dawn. So, no one is leading a gilded existence (well except for Dondi & his brothers in What Binds Us , but hell, in life most of us aren’t farting rainbows; and if someone shoves a unicorn up your ass, you’re gonna bleed.

It is often observed that my stories focus on a dark time. The observation is often buffered by the ingenuously added, “things are so much better now.”

And things have gotten better. Yes, incrementally they have but for a large portion evidently not much has changed. Our youth still struggle to come out, are often met with derision and violence when they do. Look at these statistics:

•Suicide is the second leading cause of death among young people ages 10 to 24.1

•LGBT youth seriously contemplate suicide at almost three times the rate of heterosexual youth.2

•LGB youth are almost five times as likely to have attempted suicide compared to heterosexual youth. 2

And, just last Saturday Donald Trump became the first sitting president to ever speak at a gathering of a recognized anti-gay hate group, promising them their anti-LGBT views would “no longer be silenced.”

“I am honored and thrilled,” he said, “to be the first sitting president to address this gathering of friends, so many friends.” (Read the news story here.)

AIDS

AIDS hangs like a shadow just over our shoulders for a generation of gay men, just as the Holocaust, and slavery, hangs like a shadow over the shoulder of others. We cannot forget or tidy the past.

I’m not a writer of an airbrushed, photoshopped, prettified gay experience. I tend to address what is in the world around us—drug addiction, sex work, domestic violence, the singularity of the black gay experience, and yes, AIDS.

Last week, a Mississippi High School removed To Kill a Mockingbird from its shelves because it made people uncomfortable. Isn’t that the point of fiction—to take people out of their complacency to show them truths they may not have been aware of? I know that is certainly my goal when I sit down to write.

It’s a big, bad ugly world out there, but there is also joy, and beauty, and love—if you have the courage to look for it. Same with my books.

SOURCES:

[1] CDC, NCIPC. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online]. (2010) {2013 Aug. 1}. Available from:www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars.

[2] CDC. (2016). Sexual Identity, Sex of Sexual Contacts, and Health-Risk Behaviors Among Students in Grades 9-12: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

I, like most writers with a modicum of self-control and a soupcon of good sense, don’t comment on reviews. But I do read each and every one. Mostly out of curiosity. I’m genuinely curious about what readers think of my work, of the stories I chose to tell, of the words I choose to tell them with—and yes, I realize that can be two very different things. I realize reviewers write not for writers but for other readers to either steer them to books they liked or away from others that somehow disappointed them.

I don’t read reviews to learn what readers want—I decided long ago when I started writing seriously that I wasn’t writing to market but rather writing the stories that burned in me and let the market find me. Perhaps a stupid approach—certainly not a lucrative one, but one that allows me to feel good about my work. And on those dark days, that all writers experience, when I doubt my talent and despondency threatens to consume me, I remind myself that The Great Gatsby—arguably one of the best books ever written—was, at the time it was published, a commercial failure.

Like I said, I read all my reviews and there are often common themes reflected in these. I’ve decided to address the most common themes in this post.

Timeline

While the timespan for all three off my novels vary from 10 to 40 years, all three encompass the period from the late 70s to the late 80s. Quite simply that is because that is when I came of age. I write not so much to remember as to ensure we don’t forget. I write to honor those no longer here. I write to tell their stories, to keep them present. As Lincoln says in Unbroken: “And in between all the faces that were present, all the faces that weren’t; I saw Maritza smile and Thibodeaux nod.”

All three books explore similar themes. The explanation for that is simple. I saw these three books as a sort of triptych. They are “stand-alone” novels but taken together they are a like a series of painting exploring the same subject. Somewhere in my mind there is an idea to bring the characters from all three books all together in a fourth book.

Bad things/Dark things

Sure, bad things—sometimes terrible things--happen to my characters. But with the bad there is good—just as in real life. And as in life, every night is followed by a dawn. So, no one is leading a gilded existence (well except for Dondi & his brothers in What Binds Us , but hell, in life most of us aren’t farting rainbows; and if someone shoves a unicorn up your ass, you’re gonna bleed.

It is often observed that my stories focus on a dark time. The observation is often buffered by the ingenuously added, “things are so much better now.”

And things have gotten better. Yes, incrementally they have but for a large portion evidently not much has changed. Our youth still struggle to come out, are often met with derision and violence when they do. Look at these statistics:

•Suicide is the second leading cause of death among young people ages 10 to 24.1

•LGBT youth seriously contemplate suicide at almost three times the rate of heterosexual youth.2

•LGB youth are almost five times as likely to have attempted suicide compared to heterosexual youth. 2

And, just last Saturday Donald Trump became the first sitting president to ever speak at a gathering of a recognized anti-gay hate group, promising them their anti-LGBT views would “no longer be silenced.”

“I am honored and thrilled,” he said, “to be the first sitting president to address this gathering of friends, so many friends.” (Read the news story here.)

AIDS

AIDS hangs like a shadow just over our shoulders for a generation of gay men, just as the Holocaust, and slavery, hangs like a shadow over the shoulder of others. We cannot forget or tidy the past.

I’m not a writer of an airbrushed, photoshopped, prettified gay experience. I tend to address what is in the world around us—drug addiction, sex work, domestic violence, the singularity of the black gay experience, and yes, AIDS.

Last week, a Mississippi High School removed To Kill a Mockingbird from its shelves because it made people uncomfortable. Isn’t that the point of fiction—to take people out of their complacency to show them truths they may not have been aware of? I know that is certainly my goal when I sit down to write.

It’s a big, bad ugly world out there, but there is also joy, and beauty, and love—if you have the courage to look for it. Same with my books.

SOURCES:

[1] CDC, NCIPC. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online]. (2010) {2013 Aug. 1}. Available from:www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars.

[2] CDC. (2016). Sexual Identity, Sex of Sexual Contacts, and Health-Risk Behaviors Among Students in Grades 9-12: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Published on October 18, 2017 10:27

•

Tags:

larry-benjamin, writing

September 27, 2017

The Rebranding of Larry

On June 26, I quit my job. I immediately stopped doing three things: setting my alarm, ironing clothes, and shaving. The next day I started Klonopin, an anticonvulsant often prescribed to treat panic attacks and anxiety. Five days later I sat in my doctor’s office and, in tears, admitted that for the first time in I didn’t know how long, I felt like myself. He referred me to a therapist and the work began.

With no job, and a new book set to be released August 1, I had nothing to do but work on myself and write. I needed to figure not only who I was but who I wanted to be, what I wanted to do next. Writing was a part of that. With the publication of my first book, What Binds Us, I was classified as a romance writer specifically gay romance, more commonly referred to as mm romance. I was never quite comfortable with that definition quite frankly. My books have strong romantic elements but I don’t see them as romances. Being so close to releasing In His Eyes, I really needed to think through that—especially since I hadn’t written the book’s blurb yet, and that essentially positions the book for prospective readers.

With all that going on, I didn’t think much about not shaving. In truth, I didn’t even start shaving until I was nearly 40, and then it was only twice a week. My first boyfriend in college who actually shaved daily and had chest hair, used to call me an “old smoothie.” I was comfortable being hairless. I was never particularly masculine—especially when I was younger. Facial and body hair seemed reserved for more manly men. Hell, I don’t even have hair under my arms. I stopped thinking about facial hair a long time ago.

It wasn’t until, I went to NY to have dinner with my parents and family one Sunday that I thought about it again. The first thing they said when I walked in the door was, “You look so relaxed.” Without the job-related stress, without a commute that added hours to my workday, I had begun to relax. The Klonopin muted the noise in my head and eased the tightness in my chest. With a fifth book out, which is probably the best one so far, I had relaxed into my talent as well.

The second thing they said was, “We’ve never seen you with facial hair before.” It was then that I realized the last time I had shaved was August 3 just before I went to OutWrite 2017 in DC. Other people began to notice.

My friend Shirley said, “I like it. Now you look like a writer.” Days later, a neighbor seeing me remarked, “You look so scholarly. You should write a book!” Amused, I dropped a copy of In His Eyes in his mailbox the next day.

A few weeks later, when I again visited my parents, I posted a selfie of me and my nephew Max to Facebook. It was the first time most people had seen me with facial hair. The comments poured in.

You have a beard???

Is that a beard I see?

It's so not what I think of you. It's like if you said you liked math! Who are you????

That comment echoed my husband, Stanley. When the beard care kit I ordered arrived, he stared at it, then at me and asked, Who are you?

I hadn’t meant to post a photo of the new me just yet. I was still trying to decide if I would keep it. It was a decision as weighty as the first time I pierced my ear and then later when I pierced the other one and started wearing earrings in pairs.

I had to reimagine how I saw myself—how I thought of myself. I wasn’t the type of man to have facial hair, was I? I was to sissy for that, wasn’t I? I’ve never considered myself particularly masculine and that was part of my struggle with the concept of facial hair on myself. Guys like me are supposed to be clean-shaven, aren’t they? I began to wonder if when people questioned my growing a beard, they were implying: I was too sissy for facial hair.

A few more weeks have passed and my beard is filling in. Am I going to keep it? Is it time to leave the “old smoothie” behind? Probably. It’s time for a change. I’ve always considered myself a serious writer, maybe it’s time I started looking like one. I’m still the same person but maybe it’s time to rebrand myself. And my facial hair has grown on me.

With no job, and a new book set to be released August 1, I had nothing to do but work on myself and write. I needed to figure not only who I was but who I wanted to be, what I wanted to do next. Writing was a part of that. With the publication of my first book, What Binds Us, I was classified as a romance writer specifically gay romance, more commonly referred to as mm romance. I was never quite comfortable with that definition quite frankly. My books have strong romantic elements but I don’t see them as romances. Being so close to releasing In His Eyes, I really needed to think through that—especially since I hadn’t written the book’s blurb yet, and that essentially positions the book for prospective readers.

With all that going on, I didn’t think much about not shaving. In truth, I didn’t even start shaving until I was nearly 40, and then it was only twice a week. My first boyfriend in college who actually shaved daily and had chest hair, used to call me an “old smoothie.” I was comfortable being hairless. I was never particularly masculine—especially when I was younger. Facial and body hair seemed reserved for more manly men. Hell, I don’t even have hair under my arms. I stopped thinking about facial hair a long time ago.

It wasn’t until, I went to NY to have dinner with my parents and family one Sunday that I thought about it again. The first thing they said when I walked in the door was, “You look so relaxed.” Without the job-related stress, without a commute that added hours to my workday, I had begun to relax. The Klonopin muted the noise in my head and eased the tightness in my chest. With a fifth book out, which is probably the best one so far, I had relaxed into my talent as well.

The second thing they said was, “We’ve never seen you with facial hair before.” It was then that I realized the last time I had shaved was August 3 just before I went to OutWrite 2017 in DC. Other people began to notice.

My friend Shirley said, “I like it. Now you look like a writer.” Days later, a neighbor seeing me remarked, “You look so scholarly. You should write a book!” Amused, I dropped a copy of In His Eyes in his mailbox the next day.

A few weeks later, when I again visited my parents, I posted a selfie of me and my nephew Max to Facebook. It was the first time most people had seen me with facial hair. The comments poured in.

You have a beard???

Is that a beard I see?

It's so not what I think of you. It's like if you said you liked math! Who are you????

That comment echoed my husband, Stanley. When the beard care kit I ordered arrived, he stared at it, then at me and asked, Who are you?

I hadn’t meant to post a photo of the new me just yet. I was still trying to decide if I would keep it. It was a decision as weighty as the first time I pierced my ear and then later when I pierced the other one and started wearing earrings in pairs.

I had to reimagine how I saw myself—how I thought of myself. I wasn’t the type of man to have facial hair, was I? I was to sissy for that, wasn’t I? I’ve never considered myself particularly masculine and that was part of my struggle with the concept of facial hair on myself. Guys like me are supposed to be clean-shaven, aren’t they? I began to wonder if when people questioned my growing a beard, they were implying: I was too sissy for facial hair.

A few more weeks have passed and my beard is filling in. Am I going to keep it? Is it time to leave the “old smoothie” behind? Probably. It’s time for a change. I’ve always considered myself a serious writer, maybe it’s time I started looking like one. I’m still the same person but maybe it’s time to rebrand myself. And my facial hair has grown on me.

Published on September 27, 2017 09:03

•

Tags:

beards, in-his-eyes, larry-benjamin, writing

Larry Benjamin's blog - This Writer's Life

The writer's life is as individual and strange as each writer. I'll document my journey as a writer here.

The writer's life is as individual and strange as each writer. I'll document my journey as a writer here.

...more

- Larry Benjamin's profile

- 126 followers