Paul Alkazraji's Blog, page 2

November 17, 2022

Albanians risk the choppy waters of the Channel

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay.

Comment by Paul Alkazraji

As I viewed the modern glass towers and the bare-bricked communist era apartments of my Albanian town this summer, my son showed me a TikTok advert popping up on his phone. It was for dinghy crossings to England over the Channel for £5500. “You’ve already got your air ticket,” I joked, “and it cost a lot less.” Inside, though, I was surprised at the brazenness of it, and concerned that people smuggling adverts had reached him.

Since then, the figures of how many young Albanian men have been crossing the English Channel in small boats have become clearer: around 10,000 so far this year, with another 2000 Albanian women and children (up from 50 in 2020). As Albanian middlemen have got involved along the coast of northern France, they have been recruiting back home with some apparent success.

The majority of those Albanians risking the choppy waters will be economic migrants seeking a way to a better life. Some may have been trafficked for the sex industry. Some will game the system for asylum. Some will try to disappear and work illegally before returning home to Albania later with their earnings. Some may become debt bonded to the drugs gangs, if they let them pay the cross-Channel passage for them.

Albanians have been leaving their country for decades. There was a time under Enver Hoxha when rivers were electrified, those seen escaping were shot, and you could be sent to internment for saying the cheese was better in Greece. Later when communism crumbled, Albanians packed onto cargo ships from Durres, trekked through the mountain passes into Greece, and hid in secret compartments in the back of freight lorries to get out. These days they are not fleeing violent persecution, oppression or war, but rural poverty, unemployment, low wages, poor working conditions and corruption.

In the Albanian village where I work, I have heard many migration stories first hand. One time, a young man gave me his mobile phone the night before he left. I asked myself, why? Was it because he didn’t need it anymore, and intending to buy a new one in his destination country? Then I realised it was a kind of token for his safe keeping. “Don’t forget me. Keep an eye out for me…” he was saying. A young single mother once told me how she had waded a border river illegally at night to reach a job to bring money back home for her son. I was moved by her physical courage.

In this fallen world, there are so many people seeking a better life, a place of peace where they can build a livable existence and prosper. As the push factors mount up – wars, the increasing frequency and intensity of natural disasters, crop failures, food scarcity, cost of living crises - so will the number of people seeking to enter those places that presently have some stability.

Christians know how the story will end ultimately. There will come a time when ‘nations will not raise their swords against other nations, nor will they train for war any more’, and when ‘swords are made into ploughshares and each person can sit under his own fig tree in peace and enjoy the fruit of his vine’. Until then, the authorities will need the wisdom of Solomon to filter out and exclude those individuals who would bring additional destruction and pain to the community, and in compassion give refuge too to the traumatised and vulnerable.

The Albanian Prime Minister, Edi Rama, says the present climate is ‘fueling xenophobia by singling out one community’. It is true to say that Albanians in the UK are feeling the cold wind of hostility blowing in their direction at the moment. Three times it’s been said to me that 65% of UK inmates are Albanian when the figure is nearer 2%. Someone must be spreading that. There are more than half a dozen flights every day from Tirana to the UK bringing Albanians in and out legally as they work, study and visit their relatives. My son deleted the people smuggling adverts and we hopped on the plane with them too.

Paul Alkazraji is a British writer and the author of a novel called ‘The Migrant’, which is published by Instant Apostle.

Find it on Amazon: https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B...

Read Chapter 1: https://instantapostle.com/2019/02/22...

Published on November 17, 2022 09:29

•

Tags:

albania, albanians, english-channel, migration, united-kingdom

November 4, 2022

From Albania to the English Channel

Albanians heading for the mountains. Pics, Peter Wilson.

Just why are so many young Albanian men crossing the English Channel on small boats? Their story is paralleled in Alban’s, caught in rural poverty, and heading first for Greece in ‘The Migrant’ novel.

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...

From Chapter 1.

Context: Alban Gurbardhi and his friend Ervin run into trouble as they attempt to cross the border illegally between Albania and northern Greece in search of work.

Ten minutes later, he was following the ravine back upstream until he could make out the arch of the stone bridge ahead of him. The sound of Ervin screaming and pleading had grown louder. He winced. He crawled closer on his front up a bank and set aside his sack. He peered over the edge of the clearing and he saw his friend being held by his shirt at the neck. The policeman flung him down and kicked him. Ervin moaned and rolled over.

Sliding back down lower, Alban closed his eyes. He thought about what he could do. He opened them and looked at his hands. They were trembling. He saw a broken branch by his side. It looked thick but dry and rotten. He stretched his hand towards it, and with the tips of his fingers pulled it closer and into his palm. He eased himself onto his back and began to breathe deeply. He saw his breath steam rise high in gusts. He looked up at the millions of stars in the clear Balkan night above him. In his field of vision the policeman suddenly entered and stood looking down on him. For a split second he saw his broad, muscular shoulders, his hair sheared close across his temples, and his eyes – yet one was odd. In fear and panic he brought the branch up into the man’s face and it smashed there into pieces. The man groped at his eyes and tumbled down the bank.

Alban got to his feet, grabbed his sack and ran towards Ervin. He pulled him up off the ground and looked at his face. It was dark and blood-sticky.

‘Hey, friend. Are you coming with me to Greece?’ he shouted. A grin broke across Ervin’s dazed face. Alban clutched his shirt and dragged him forwards, stumbling over the clearing. They tore down the edge of the treeline together. Soon they were running parallel to the ravine. Alban’s sack caught a branch and was snagged from his hand. He stopped to retrieve it. He looked back. The policeman was up now and coming.

They came to a rocky hillock and bounded up it like young goats and then down the other side into a hedge of rosehip bushes. Ervin waded through them ahead lifting the long fronds aside so that they would not snap back on him. Alban, though, felt the thorns of one cut into the flesh of his shoulder and he cried out. They tumbled out of the other side onto the grass and crawled forward until they came to the edge of the land. Alban looked down. Below them was an almost sheer bank of earth falling to the rocky bed of the stream perhaps fifty metres down. He looked out over the mountains before them. The moonlight caught a row of wind turbines on a distant ridgeline. He could smell Ervin’s sweat and blood. He thought he heard the bear growl far away, but he was sure he heard a man grunt and spit. He turned to look behind them. On the top of the hillock the policeman stood against the stars. He reached his hand down to the holster on his thigh and drew out the fat, black pistol.

‘You little dogs!’ he shouted. He mounted it across his right forearm with his left hand. Alban grabbed his friend’s arm and dragged him over the edge as two shots cracked out and echoed along the ravine.

Copyright Paul Alkazraji, Instant Apostle.

The first two chapters can be read here:

https://read.amazon.com/kp/embed?prev...

A good day's wage in Albania (1200 leke/£8.90) making work over the border in Greece and in Northern Europe a prospect many see as worth taking risks for.

For more about 'The Migrant' click on the cover:

October 14, 2022

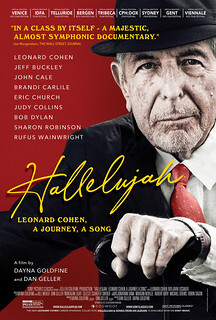

‘Hallelujah’ – A song brought back from obscurity

‘I heard there was a secret chord, that David played and it pleased the Lord,’ begins Leonard Cohen’s much-loved song ‘Hallelujah’, the seam around which this new documentary ‘Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song’ holds together. So like that chord, one can wonder if the popular ‘hymn’ pleased the true Lord of song too.

This September, I settled into the velvet ambiance of a little theatre in England with a cup full of pick-n-mix to enjoy both the sugary and matinee treats. As well as the biographical elements, the story of the song was fascinating indeed. The album on which it was first recorded, ‘Various Positions’ in 1984, was, incredibly, refused release in the USA. Columbia records gave the work and its producer John Lissauer such a damning vote of zero confidence that they both seemed consigned to obscurity.

Yet the song was later picked up and sung by Bob Dylan, John Cale and Rufus Wainwright. It was given a jet-boosting by Jeff Buckley and then the Shrek film version (without the ‘naughty bits’ as co-director Vicky Jenson explains) before becoming the supersonic standard of TV talent show spectaculars and taking on a life of its own. A trajectory with ‘a fourth, a fifth, a minor fall, and a major lift’ indeed.

With its religious and sexual imagery drawn from the Bible’s accounts of King David and Bathsheba, Samson and Delilah, it mixes the sacred and the profane in a hymn of sorts, though not of ‘somebody who's seen the light’. Cohen, a spiritual seeker, did not seem to find David’s Lord for himself.

It was when Mr Cohen went to the bank’s ATM, and realised his business manager had stolen all his earnings, that he was compelled to go back out on the road once more in 2008, by now in his early-seventies, with a band of superb musicians. On the opening night, we see his undoubted charm as he sings in tones that sink down deep as a cavern: ‘I was born like this/ I had no choice/ I was born with the gift of a golden voice.’ Sell out tours, where the bookings kept coming, lasted for five years. They were the swansong of his life.

The story that I liked, though, was of how a quality piece of writing (150 to 180 song verses that still remained a work in progress) could so easily have been lost in the archives of time as a record label reject. Yet it found unanticipated champions that brought it an incredible level of public attention decades later. It points up just how many more of the fine works of others may have fallen the same anonymous way, but also to the tantalising possibility of just what can, and might yet, happen to a writer’s buried gems. Hallelujah!

Pic, Rama. Cohen in 2008

Recommended reading:

The Holy or the Broken: Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley, and the Unlikely Ascent of "Hallelujah"

Recommended watching:

Leonard Cohen - Hallelujah (Live In London)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YrLk4...

By this writer:

Published on October 14, 2022 04:21

•

Tags:

bob-dylan, hallelujah, jeff-buckley, john-cale, leonard-cohen, poem, rufus-wainwright, shrek, song

July 21, 2022

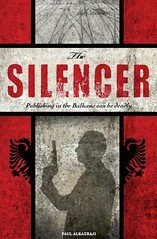

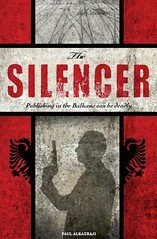

New excerpts from 'The Silencer' (2).

Chapter 19

(Thessaloniki to Kastoria).

The coach’s hydraulic brakes let out stuttering hisses

to accompany the high beeps of its reversing alarm.

Sheref watched the silver dome of the Macedonia

Coach Terminal glint in the sun and slip away on

his right behind him. The ‘KTEL’ ticket office there

had informed him that the journey to Kastoria in

northwest Greece would take around four hours.

He knew that it would then be only a short taxi

ride to the nearby Albanian border. He reflected

momentarily on the morning. He had woken just

after 7.00am, paid cash and collected his passport

from the Hotel Persephone receptionist: she with

the cherry lipstick, who had again maddeningly

avoided eye contact with him. He had then waved

down a dark blue Mercedes taxi on Monastiriou

Street for the short drive to the terminal. He checked

his watch: it read 9.06am, Sunday, August 24th. The

coach was half full with passengers, all Greeks he

thought, and he had taken a seat over the rear left

wheel arch with no one immediately to his front or

right for removal from close contact with them. The

sun was already burning the left side of his head. He

drew the pleated orange curtain halfway across the

window for shade, and to psychologically fortify his

private enclosure.

Sheref took out the road map and guidebook

from his backpack and tossed them on the empty

seat beside him. The coach began to accelerate past

tall cranes angled in the city’s port before the hazy

blue Gulf of Thermi, and billboards for concerts with

silver-moustached musicians, before filtering onto

the Via Egnatia Motorway. He slunk a little lower in

the seat and watched the oncoming flow of traffic to

his left.

A stretch of water flashed by below the roadside

fence and he checked his map. It was probably the

River Axios Vardaris, he thought. The coach shortly

began to slow and he sat up to peer forwards. Lanes

of traffic were queuing ahead into a wide row of

booths. Above them was a line of blue signs, each

with a white outline of a man wearing a flat-topped,

peaked cap like a French gendarme. He felt his

backpack pockets hastily to locate his passport. He

hunched his shoulders around himself a little and

pressed his fingers into the palms of his hands. As

the traffic edged closer to the row of rising and

falling barriers, he reassured himself that it was just

a road toll station. As they passed through, on the

right side there were parked lorries, and Kantina

vans smoking from griddle meat with chairs set

out on decks for customers. A Greek policeman

slouched on the front wing of his white car drinking

from a polystyrene cup. He rose and lifted his

mobile phone to his ear closely watching the coach

pass. When Sheref released his clench, rows of white

dimples were imprinted on his palms.

He took a gulp of mineral water from a small,

plastic bottle and splashed some over his face to

ease the heat. He ran his finger and thumb around

the edges of his top lip to clear off the sweat. He

watched the bushes blooming with pink flowers in

the lay-bys pass, and soon he was looking out across

orchards of peach trees dotted with the pulsing

sprays of water sprinklers. Away to the south, above

lower slopes darkened by forest, a high ridge of

jagged peaks rose up still tipped with snow. That,

I think, must be Mount Olympus, he observed

flicking through his guidebook: Greece’s highest

mountain, chosen by the ancients as the abode of

their gods, Zeus, Poseidon and Hades. A pang of

yearning seemed to escape from some cavern deep

within him. His thoughts moved to Hanife and her

submission to the religion of his land, but he? Who

did he follow? Well, he had his path now with its

own motion and trajectory. Where was that coffee

shop hag’s guide: remote with Zeus, or with him?

“Haydi!” he whispered. She’d cheated him of two

good lira and laughed at his back! He took out his

camera, pointed it roughly at Olympus, and pressed

the shutter button a few times. He circled it with a

pen in the book. He glanced over the nearby entry

for the Royal Tombs of Vergina, the first capital of

Macedon, thought to house the remains of Alexander

the Great’s son, and where King Philip II was

assassinated. He circled that too for good measure.

He noticed a road sign for the town of Veria pass

on his right, and then the motorway began to climb.

The coach’s engine growled against the incline and

they passed into the shade of a road tunnel and then

another one. When they entered the third one he

began keeping count. His eyes passed over the green

lights and arrows above the lanes, the signs to turn

on headlights, and those with the tunnels’ length.

Still they kept coming and he saw that the tenth one

was 2.2km long. Here in the extended darkness he

watched the wall lights, white on his left and red

on his right, streaming past. Fans, like jet turbines,

fastened to the roof, seemed to him to be propelling

him forwards like a bullet down a barrel. Before the

thirteenth tunnel, he saw a sign saying ‘Call 1077 in

an emergency’.

The coach rocked along past a row of unmanned

tollbooths and the motorway began to descend

gradually into a wide, flat valley. They passed

under a line of pylons crossing the plain, their heads

horned and arms hanging at the elbows clutching

cables as they filed towards a distant power station.

He stared ahead. There detachments of them converged

to fetch and carry electricity. High red and

white striped chimneys rose among them, and from

a cooling tower a cloud of steam arched into the sky

like a giant question mark.

A rocky outcrop with a pinnacle like some

straying child below it passed by close to the motorway’s

edge, and soon it swept through a pass in a

range of hills running left to right. As the driver drew

off the slip road at Siatista, a squat factory chimney

made of bricks caught his eye. He checked the time: it

was just before mid-day. They now took a main road

that wound through woods and open country with

mountains, dry, brown and bare, to his right, and

hills lower and undulating to his left. He thought

he felt something like the brushing of silk pass over

the skin of his right arm. He touched it. Road works

and yellow earthmoving vehicles parked by a wide,

empty stretch of pristine tarmac came into view. A

strange new lightness of heart had come over him.

It was a feeling of wellbeing, an inner warmth not

sensed since childhood. He became aware that he

had been feeling like this for perhaps ten minutes.

He turned to see a man sitting in the aisle seat

on his right. His arms flinched slightly into his chest

with the shock. How long had he been sitting there?

How could it be that he had not seen nor heard him

come? The man was staring straight ahead and did

not look back at him. He wore a plain white T-shirt

and light fawn trousers. His black hair flowed onto

his shoulders thick and fragrant with a sweet aroma

that Sheref now breathed in. He found himself

staring at the man’s face: a strong and shapely nose

and eyes with a beauty that was almost feminine.

His nationality was not apparent: Greek, Turk or

Albanian, nor his age. Then he thought he heard the

words: “Go back to your father.” A feeling of cool

air being blown onto his cheek made him touch it.

He lifted his head to check the air-con valve but it

was off. As he did so it was as if he rose outside of

himself. Questions about what he was undertaking

seemed suddenly to touch him. Where am I going?

What is this I’m doing? Light, like the reflection of

the sun flashing off a mirror or window, caught his

eyes and dazzled him momentarily. He covered

them with his hand and then removed it. He turned

his head again to the man. He was no longer there.

He yanked himself up by the seat in front to see if

he was moving down the coach. There was no one

in the aisle.

He saw a sign with ‘Kastoria’ written on it, and

soon the road was skirting the shore of a lake on his

right-hand side. A couple of smart hotels passed by

and a warehouse with an illuminated sign above it

where a model pressed a thick fur coat to her neck.

Through gaps in the buildings he caught glimpses

across greeny-blue water to a peninsular of land with

white houses stacked up its steep sides. He scanned

the guidebook entry for the town. Kastori was Greek

for beaver, once central to the local fur trade. He

took out a pen but somehow did not follow through

in circling it.

The coach pulled up in a car park by a taxi

rank and a row of quiet shops and cafes. He looked

keenly for the man with the feminine eyes as he

disembarked, but he did not see him. He bought some

pastries from a baker’s and ate them as he stared

across a children’s playground to the lake. A couple

of swans skimmed over the water’s surface as they

landed by a patch of reeds. Wooden rowing boats

bobbed at their moorings there, one striped with the

blue and white colours of the Greek flag, with green

fishing nets draped across them.

Sheref walked to a cafe and sat in the shade of its

canopy on a low, leather sofa. The waiter set down a

bottle of mineral water, cool with condensation, on

the glass coffee table before him and he ordered an

iced latte. His mind kept returning to the man on

the bus. An odd, yet pleasant, bemusement lingered

from the incident that he was trying to process. He

took out his mobile phone and turned it on. He then

fiddled with it a little; the back light was now flickering

and the 7 button was functioning only intermittently.

He shook it and tapped it. Why had he not

fixed it? The latte was brought and he sipped it a

little and drank a glass of water. His phone began

to vibrate, rattling loudly on the coffee table glass.

It was Hanife! He looked at it for a few seconds and

then picked it up.

“Sheref! Where are you?” he heard her say anxiously.

“Why was your phone off? I’ve been trying to call you!”

“I’m in Greece…” An answer came to him: “You

know what roaming rates are like!”

“What are you doing?”

“I’m just drinking a coffee. There’s a… nice lake

here.”

“Don’t be angry with me… I told baba that you

were going to Albania.”

“Why did you do that?” he shouted curtly.

“He’s here.”

“What? No I don’t want to...”

“Sheref?” The sound of his father’s voice made

him screw up his eyes tightly. He’d said his name

softly, without accusation or reproach, for the first

time in so long. Sheref lowered the phone to his

chest for a moment. He swallowed. A tear welled

up and it fell with a ‘pat’ onto his thigh. He could

hear his father saying his name repeatedly, anxious

they’d been cut off.

“Yes?”

“I have… this fine new samovar… at the Bazaar.

It makes good tea… that is to say… when you have

seen those Arnavutlar.” Sheref understood what he

was trying to say.

“Yes baba,” he said. A few moments of silence

passed and Sheref pressed the red button to end the

call. He lowered his head and his shoulders shook as

he sobbed. He brushed his cheeks quickly with his

fingers, checked the receipt, and left his unfinished

latte and three euros on the table.

He walked over a patch of dry grassy ground and

then across a road to a pavement along the water’s

edge. He followed it thinking. The trees by the shore

had been painted with skirts of whitewash. There

were more cafes here with their tables arranged

under the shade of canopies, mobiles tingling above

them in the mild breeze. He passed a small boy with

a face smeared with pink ice cream rocking happily

on a child’s ride. White, timbered mansions rose

up the hillside on his left, and conifer trees clung to

the rocky hillsides around. He sat down on a bench

affected by the peace of the place. There he watched

a man casting his rod and line out across the water

and he thought of the Galata Bridge and the waters

of the Golden Horn. The high, afternoon sun blazed

off the surface, and a white sail turned slowly in

the shimmering glare and moved back towards

land. He had made a decision. He would stay here

tonight. Tomorrow, yes, let it be so, he would return

to Istanbul.

Paul Alkazraji.

Copyright Paul Alkazraji. Highland Books Ltd. 2012. All Rights Reserved.

Find ‘The Silencer’ on Amazon.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B...

Also by this author.

(Thessaloniki to Kastoria).

The coach’s hydraulic brakes let out stuttering hisses

to accompany the high beeps of its reversing alarm.

Sheref watched the silver dome of the Macedonia

Coach Terminal glint in the sun and slip away on

his right behind him. The ‘KTEL’ ticket office there

had informed him that the journey to Kastoria in

northwest Greece would take around four hours.

He knew that it would then be only a short taxi

ride to the nearby Albanian border. He reflected

momentarily on the morning. He had woken just

after 7.00am, paid cash and collected his passport

from the Hotel Persephone receptionist: she with

the cherry lipstick, who had again maddeningly

avoided eye contact with him. He had then waved

down a dark blue Mercedes taxi on Monastiriou

Street for the short drive to the terminal. He checked

his watch: it read 9.06am, Sunday, August 24th. The

coach was half full with passengers, all Greeks he

thought, and he had taken a seat over the rear left

wheel arch with no one immediately to his front or

right for removal from close contact with them. The

sun was already burning the left side of his head. He

drew the pleated orange curtain halfway across the

window for shade, and to psychologically fortify his

private enclosure.

Sheref took out the road map and guidebook

from his backpack and tossed them on the empty

seat beside him. The coach began to accelerate past

tall cranes angled in the city’s port before the hazy

blue Gulf of Thermi, and billboards for concerts with

silver-moustached musicians, before filtering onto

the Via Egnatia Motorway. He slunk a little lower in

the seat and watched the oncoming flow of traffic to

his left.

A stretch of water flashed by below the roadside

fence and he checked his map. It was probably the

River Axios Vardaris, he thought. The coach shortly

began to slow and he sat up to peer forwards. Lanes

of traffic were queuing ahead into a wide row of

booths. Above them was a line of blue signs, each

with a white outline of a man wearing a flat-topped,

peaked cap like a French gendarme. He felt his

backpack pockets hastily to locate his passport. He

hunched his shoulders around himself a little and

pressed his fingers into the palms of his hands. As

the traffic edged closer to the row of rising and

falling barriers, he reassured himself that it was just

a road toll station. As they passed through, on the

right side there were parked lorries, and Kantina

vans smoking from griddle meat with chairs set

out on decks for customers. A Greek policeman

slouched on the front wing of his white car drinking

from a polystyrene cup. He rose and lifted his

mobile phone to his ear closely watching the coach

pass. When Sheref released his clench, rows of white

dimples were imprinted on his palms.

He took a gulp of mineral water from a small,

plastic bottle and splashed some over his face to

ease the heat. He ran his finger and thumb around

the edges of his top lip to clear off the sweat. He

watched the bushes blooming with pink flowers in

the lay-bys pass, and soon he was looking out across

orchards of peach trees dotted with the pulsing

sprays of water sprinklers. Away to the south, above

lower slopes darkened by forest, a high ridge of

jagged peaks rose up still tipped with snow. That,

I think, must be Mount Olympus, he observed

flicking through his guidebook: Greece’s highest

mountain, chosen by the ancients as the abode of

their gods, Zeus, Poseidon and Hades. A pang of

yearning seemed to escape from some cavern deep

within him. His thoughts moved to Hanife and her

submission to the religion of his land, but he? Who

did he follow? Well, he had his path now with its

own motion and trajectory. Where was that coffee

shop hag’s guide: remote with Zeus, or with him?

“Haydi!” he whispered. She’d cheated him of two

good lira and laughed at his back! He took out his

camera, pointed it roughly at Olympus, and pressed

the shutter button a few times. He circled it with a

pen in the book. He glanced over the nearby entry

for the Royal Tombs of Vergina, the first capital of

Macedon, thought to house the remains of Alexander

the Great’s son, and where King Philip II was

assassinated. He circled that too for good measure.

He noticed a road sign for the town of Veria pass

on his right, and then the motorway began to climb.

The coach’s engine growled against the incline and

they passed into the shade of a road tunnel and then

another one. When they entered the third one he

began keeping count. His eyes passed over the green

lights and arrows above the lanes, the signs to turn

on headlights, and those with the tunnels’ length.

Still they kept coming and he saw that the tenth one

was 2.2km long. Here in the extended darkness he

watched the wall lights, white on his left and red

on his right, streaming past. Fans, like jet turbines,

fastened to the roof, seemed to him to be propelling

him forwards like a bullet down a barrel. Before the

thirteenth tunnel, he saw a sign saying ‘Call 1077 in

an emergency’.

The coach rocked along past a row of unmanned

tollbooths and the motorway began to descend

gradually into a wide, flat valley. They passed

under a line of pylons crossing the plain, their heads

horned and arms hanging at the elbows clutching

cables as they filed towards a distant power station.

He stared ahead. There detachments of them converged

to fetch and carry electricity. High red and

white striped chimneys rose among them, and from

a cooling tower a cloud of steam arched into the sky

like a giant question mark.

A rocky outcrop with a pinnacle like some

straying child below it passed by close to the motorway’s

edge, and soon it swept through a pass in a

range of hills running left to right. As the driver drew

off the slip road at Siatista, a squat factory chimney

made of bricks caught his eye. He checked the time: it

was just before mid-day. They now took a main road

that wound through woods and open country with

mountains, dry, brown and bare, to his right, and

hills lower and undulating to his left. He thought

he felt something like the brushing of silk pass over

the skin of his right arm. He touched it. Road works

and yellow earthmoving vehicles parked by a wide,

empty stretch of pristine tarmac came into view. A

strange new lightness of heart had come over him.

It was a feeling of wellbeing, an inner warmth not

sensed since childhood. He became aware that he

had been feeling like this for perhaps ten minutes.

He turned to see a man sitting in the aisle seat

on his right. His arms flinched slightly into his chest

with the shock. How long had he been sitting there?

How could it be that he had not seen nor heard him

come? The man was staring straight ahead and did

not look back at him. He wore a plain white T-shirt

and light fawn trousers. His black hair flowed onto

his shoulders thick and fragrant with a sweet aroma

that Sheref now breathed in. He found himself

staring at the man’s face: a strong and shapely nose

and eyes with a beauty that was almost feminine.

His nationality was not apparent: Greek, Turk or

Albanian, nor his age. Then he thought he heard the

words: “Go back to your father.” A feeling of cool

air being blown onto his cheek made him touch it.

He lifted his head to check the air-con valve but it

was off. As he did so it was as if he rose outside of

himself. Questions about what he was undertaking

seemed suddenly to touch him. Where am I going?

What is this I’m doing? Light, like the reflection of

the sun flashing off a mirror or window, caught his

eyes and dazzled him momentarily. He covered

them with his hand and then removed it. He turned

his head again to the man. He was no longer there.

He yanked himself up by the seat in front to see if

he was moving down the coach. There was no one

in the aisle.

He saw a sign with ‘Kastoria’ written on it, and

soon the road was skirting the shore of a lake on his

right-hand side. A couple of smart hotels passed by

and a warehouse with an illuminated sign above it

where a model pressed a thick fur coat to her neck.

Through gaps in the buildings he caught glimpses

across greeny-blue water to a peninsular of land with

white houses stacked up its steep sides. He scanned

the guidebook entry for the town. Kastori was Greek

for beaver, once central to the local fur trade. He

took out a pen but somehow did not follow through

in circling it.

The coach pulled up in a car park by a taxi

rank and a row of quiet shops and cafes. He looked

keenly for the man with the feminine eyes as he

disembarked, but he did not see him. He bought some

pastries from a baker’s and ate them as he stared

across a children’s playground to the lake. A couple

of swans skimmed over the water’s surface as they

landed by a patch of reeds. Wooden rowing boats

bobbed at their moorings there, one striped with the

blue and white colours of the Greek flag, with green

fishing nets draped across them.

Sheref walked to a cafe and sat in the shade of its

canopy on a low, leather sofa. The waiter set down a

bottle of mineral water, cool with condensation, on

the glass coffee table before him and he ordered an

iced latte. His mind kept returning to the man on

the bus. An odd, yet pleasant, bemusement lingered

from the incident that he was trying to process. He

took out his mobile phone and turned it on. He then

fiddled with it a little; the back light was now flickering

and the 7 button was functioning only intermittently.

He shook it and tapped it. Why had he not

fixed it? The latte was brought and he sipped it a

little and drank a glass of water. His phone began

to vibrate, rattling loudly on the coffee table glass.

It was Hanife! He looked at it for a few seconds and

then picked it up.

“Sheref! Where are you?” he heard her say anxiously.

“Why was your phone off? I’ve been trying to call you!”

“I’m in Greece…” An answer came to him: “You

know what roaming rates are like!”

“What are you doing?”

“I’m just drinking a coffee. There’s a… nice lake

here.”

“Don’t be angry with me… I told baba that you

were going to Albania.”

“Why did you do that?” he shouted curtly.

“He’s here.”

“What? No I don’t want to...”

“Sheref?” The sound of his father’s voice made

him screw up his eyes tightly. He’d said his name

softly, without accusation or reproach, for the first

time in so long. Sheref lowered the phone to his

chest for a moment. He swallowed. A tear welled

up and it fell with a ‘pat’ onto his thigh. He could

hear his father saying his name repeatedly, anxious

they’d been cut off.

“Yes?”

“I have… this fine new samovar… at the Bazaar.

It makes good tea… that is to say… when you have

seen those Arnavutlar.” Sheref understood what he

was trying to say.

“Yes baba,” he said. A few moments of silence

passed and Sheref pressed the red button to end the

call. He lowered his head and his shoulders shook as

he sobbed. He brushed his cheeks quickly with his

fingers, checked the receipt, and left his unfinished

latte and three euros on the table.

He walked over a patch of dry grassy ground and

then across a road to a pavement along the water’s

edge. He followed it thinking. The trees by the shore

had been painted with skirts of whitewash. There

were more cafes here with their tables arranged

under the shade of canopies, mobiles tingling above

them in the mild breeze. He passed a small boy with

a face smeared with pink ice cream rocking happily

on a child’s ride. White, timbered mansions rose

up the hillside on his left, and conifer trees clung to

the rocky hillsides around. He sat down on a bench

affected by the peace of the place. There he watched

a man casting his rod and line out across the water

and he thought of the Galata Bridge and the waters

of the Golden Horn. The high, afternoon sun blazed

off the surface, and a white sail turned slowly in

the shimmering glare and moved back towards

land. He had made a decision. He would stay here

tonight. Tomorrow, yes, let it be so, he would return

to Istanbul.

Paul Alkazraji.

Copyright Paul Alkazraji. Highland Books Ltd. 2012. All Rights Reserved.

Find ‘The Silencer’ on Amazon.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B...

Also by this author.

April 7, 2022

From Russia with Love

Photo by Peter Wilson.

Comment: From Russia with Love

By Paul Alkazraji

A woman plays Chopin one last time on a piano in the rubble of her home near Kyiv. A little girl at the Polish border says a window exploded during her city’s siege, and all the batteries in her toys ran out. A man tells how he left behind people surviving on scraps of food and boiled snow, and fled through the rubble and dead bodies without his shoes. Such are the fragmented impressions of many, like ‘shrapnel in the mind’, as the war in Ukraine continues.

These weeks, we have become inured to Russia’s public statements, the smoke and mirrors of them, even whilst knowing that camouflage and surprise are, of course, military tactics. A simple layperson’s guide seems to be: read the opposite. ‘We are not going to invade Ukraine… The Ukrainians are preparing chemical weapons for use… The Ukrainians are using actors to fake casualties and spread a false narrative on social media.’ In Communist countries public statements were always about the glory of the State and not reality. Now, this information war bombards the truth even as atrocities are uncovered. We have also seen Putin threaten the use of his nuclear arsenal, which would, as Sting once sang, ‘Be such an ignorant thing to do if the Russians love their children too.’

There has been a tectonic shift in the geo-political ground, and when the war has run its course, what might follow from an isolated pariah Russia and its allies? ‘The world is changing Frodo…’ and when you look at the signs of the times, the prospect seems bleak. We wish we were not seeing these things; ‘so do all who live to see such times…’ says Gandalf. But just where is there ground for hope? Dare I say it, surely only on the ‘Rock of Ages’.

In a novel I wrote called ‘The Migrant’, in addition to the sanctuary and aid refugees and migrants can receive on arriving in new countries having left their conflict zones, the dangers that await them are looked at too. There is the rise of far right political groups and racist attacks, and criminal gangs that prey on people’s vulnerability. Nevertheless, the ultimate source of hope is also pointed to.

‘There are so many people searching for… a place where there is peace, just to call it home,’ says one character in the book.

‘Hasn’t it always been like that?’ says another.

‘Since the beginning, but it won’t always be so,’ replies the first. ‘There will come a time when, “Nations will not raise their swords against other nations, nor will they train for war any more. He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.”’

It’s been noted for some time that Russia has been trying to undermine and destabilize Western democracies by stoking conflict and division inside and between them. Whether unanticipated or calculated by the Kremlin, four million refugees and counting, numbers unprecedented since World War Two, have now been driven into Europe’s burden of care… ‘From Russia with Love’.

Kyiv bombardment.

Photo by Julia Rekamie on Unsplash.

Links.

A woman plays Chopin one last time.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DDUdK...

Sting sings 'Russians'.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wHylQ...

By this writer:

February 24, 2022

Psalm 40-09-19

Psalm 40-09-19

Praise The Company, my soul!

O Company, how great you are!

You are clothed in glass and steel;

you spread out your buildings

across the cities

and built your home

in the penthouse above.

You use the telex machine

as your chariot

and flashes of data as your servants.

You ride on the wings

of your digital communications networks.

You set your office block

firmly on its foundations.

You spoke and your employees responded;

at the shout of your command

there were cashpoint dispensers

at the four corners of the nation.

You make water flow in the toilets

and there the wild office juniors

quench their thirst.

Praise The Company, my soul!

O Company, how great you are!

O Company, I am in great pain,

my heart is troubled

and my eyes have lost their brightness.

Because I have been foolish

I am drowning in the flood of my debts;

they are a burden too heavy to bear.

All night long my creditors plot against me;

they are like lions waiting for me

wanting to tear me to pieces.

O Company, don’t let them gloat over my distress.

You have examined my financial history

and you know everything I do;

from far away you understand all my thoughts.

Where could I go to escape your influence?

If I flew away beyond the NatWest,

you would find me.

If I lay down in the world of the dead,

you would have a branch office there.

Have mercy upon me, O Company

according to your unfailing love.

In your compassion

cancel all of my debts,

clear out all of my records,

wash away the stain of my defaults.

Look at my suffering

and restore my wealth

and I will meditate

on my future fiscal obligations.

Hear my prayer, O Company!

Forgive me all that has passed

so that I may rejoice and sing

in the shadow of your protection;

so that I may proclaim

to the people of all nations

that you reign with justice and mercy

and that you have not abandoned me.

Praise The Company, my soul!

O Company, how great you are!

A psalm I wrote in response to some of the pseudo-divine pretentions of UK banks and building societies in their TV advertisement campaigns of the time.

By this writer:

February 18, 2022

The Albania to Athens quiz

Check your general knowledge of Albania and Greece. Try this free, easy quiz on Goodreads drawn from my novel ‘The Migrant’.

What is the road border crossing from Albania to Greece (near Bilisht) called by people on the Albanian side?

Who was the Prime Minister of Greece in September 2012 when events in the story are set?

The quiz is here: https://www.goodreads.com/quizzes/113...

November 5, 2021

Migrants make for the mountains

Albanians heading for the mountains. Pics, Peter Wilson.

Excerpt from 'The Migrant' novel: A suspense story about a British Pastor, Jude Kilburn, as he travels to Athens to find an Albanian member of his church, Alban Gurbardhi, who has migrated there illegally in search of a better life. This as the riots surrounding Greece’s recent economic collapse explode, and a neo-Nazi movement closes in for a fatal, racist attack on Alban.

From Chapter 1.

Context: Alban Gurbardhi and his friend Ervin run into trouble as they attempt to cross the border illegally between Albania and northern Greece in search of work.

Ten minutes later, he was following the ravine back upstream until he could make out the arch of the stone bridge ahead of him. The sound of Ervin screaming and pleading had grown louder. He winced. He crawled closer on his front up a bank and set aside his sack. He peered over the edge of the clearing and he saw his friend being held by his shirt at the neck. The policeman flung him down and kicked him. Ervin moaned and rolled over.

Sliding back down lower, Alban closed his eyes. He thought about what he could do. He opened them and looked at his hands. They were trembling. He saw a broken branch by his side. It looked thick but dry and rotten. He stretched his hand towards it, and with the tips of his fingers pulled it closer and into his palm. He eased himself onto his back and began to breathe deeply. He saw his breath steam rise high in gusts. He looked up at the millions of stars in the clear Balkan night above him. In his field of vision the policeman suddenly entered and stood looking down on him. For a split second he saw his broad, muscular shoulders, his hair sheared close across his temples, and his eyes – yet one was odd. In fear and panic he brought the branch up into the man’s face and it smashed there into pieces. The man groped at his eyes and tumbled down the bank.

Alban got to his feet, grabbed his sack and ran towards Ervin. He pulled him up off the ground and looked at his face. It was dark and blood-sticky.

‘Hey, friend. Are you coming with me to Greece?’ he shouted. A grin broke across Ervin’s dazed face. Alban clutched his shirt and dragged him forwards, stumbling over the clearing. They tore down the edge of the treeline together. Soon they were running parallel to the ravine. Alban’s sack caught a branch and was snagged from his hand. He stopped to retrieve it. He looked back. The policeman was up now and coming.

They came to a rocky hillock and bounded up it like young goats and then down the other side into a hedge of rosehip bushes. Ervin waded through them ahead lifting the long fronds aside so that they would not snap back on him. Alban, though, felt the thorns of one cut into the flesh of his shoulder and he cried out. They tumbled out of the other side onto the grass and crawled forward until they came to the edge of the land. Alban looked down. Below them was an almost sheer bank of earth falling to the rocky bed of the stream perhaps fifty metres down. He looked out over the mountains before them. The moonlight caught a row of wind turbines on a distant ridgeline. He could smell Ervin’s sweat and blood. He thought he heard the bear growl far away, but he was sure he heard a man grunt and spit. He turned to look behind them. On the top of the hillock the policeman stood against the stars. He reached his hand down to the holster on his thigh and drew out the fat, black pistol.

‘You little dogs!’ he shouted. He mounted it across his right forearm with his left hand. Alban grabbed his friend’s arm and dragged him over the edge as two shots cracked out and echoed along the ravine.

Copyright Paul Alkazraji, Instant Apostle.

The first two chapters can be read here:

https://read.amazon.com/kp/embed?prev...

A good day's wage in Albania (1200 leke/£8.40) making work over the border in Greece a prospect many see as worth taking risks for.

For more about 'The Migrant' click on the cover:

September 6, 2021

'The Migrant' blog tour 2021

'The Migrant': Three incompatible characters set off from Albania on a dangerous journey to find a missing relative in Athens at the time of Greece’s economic crisis, encountering police brutality, racism and restored relationships along the way.

Follow the blog tour here as seven writers share their thoughts about the novel...

Blog Tour #1 'And what... makes this novel so good, well to start with its the main character, Pastor Jude Kilburn as he is taken through a perilous journey...' says Lynsey Adams. (Scroll down a little.)

https://readingbetweenthelines4067781...

Blog Tour #2 A very thoughtful and engaged review from S C Skillman. @scskillman

https://scskillman.com/2021/09/07/boo...

September 5, 2021

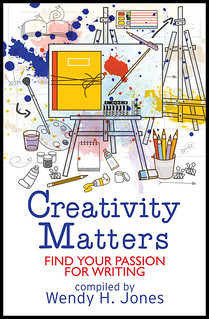

A rich storehouse for writers

‘Creativity Matters’ is a collection of articles by thirteen writers on what makes them passionate about a chosen genre, including drama, humour, memoir, children’s books and more.

Collated and published by Wendy H Jones, President of The Scottish Association of Writers and member of the Association of Christian Writers, it is a book to fuel the creativity of everyone from the tentative toe-dipper to the hard-boiled hack. Some of my favourite points follow.

Wendy considers in her first chapter ‘Why write?’ the need for writers to be well-read readers, and challenges us to check the setting on our mobile devices to see how many hours we spend there before we excuse ourselves by talking of a lack of time to read.

In her chapter ‘Why write crime or mystery?’ (which I made directly for having written two thrillers), she lists all the sub-genres from ‘Police Procedural’ to ‘Supernatural’ and given the high sales of this genre says that ‘one of the top reasons why you should consider writing crime (is) you will have no shortage of readers and the genre will remain popular for many years to come’. She notes that it allows both authors and readers to ‘flirt on the edge of danger without being in danger themselves’. A key challenge is ‘to ensure that the plot is complex enough to fool the reader yet make it simple enough that by the final denouement the reader is saying, why didn’t I see that?’ How well put.

In Maressa Mortimer’s chapter ‘Why write faith books?’ she discusses in working out how a character would react in a given situation, you can examine them and allow God to work through them to change and shape you. An author can be so much more involved if you write their story, she notes, rather than remaining with just a list of their characteristics. ‘Forgiveness is no longer something good people simply do, but we can feel the struggle when a character is hurt’. By sharing your message in story form, it can be more relatable and accessible to people; writing faith stories can be such a help to us all she says. Amen sister.

Wendy has a positive, can-do, uplifting attitude here that is a wellspring to those stumbling along in dry places. There is a rich storehouse too of inspiring ideas and encouraging insights from a host of writers to help you find your creative spark, step out on the writing road, and even find fresh inspiration to branch out.

Links for Wendy H Jones

WEBSITE

https://www.wendyhjones.com

https://www.facebook.com/wendyhjonesa...

@WendyHJones

AMAZON AUTHOR PAGE

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Wendy-H.-Jon...

https://www.instagram.com/wendyhjones/

By this reviewer:

Published on September 05, 2021 07:48

•

Tags:

authors, inspiration, training, writing