Paul Finch's Blog, page 11

December 29, 2018

Eerie East Anglia, above and below ground

Well, it’s not quite New Year yet, but this is likely to be the last time I speak to you all before 2019, so it seems an appropriate time to say Happy New Year and to wish you all every success and prosperity in the months ahead.

On the personal front, my next novel, STOLEN, which is book 3 in the Lucy Clayburn saga, will be published on May 16. That’s some way off yet, I know, and as such, I still haven’t got any cover artwork for you. But the official back-cover blurb has now appeared online, and so I’m going to run that today before I do anything else.

Staying on the subject of lady cops, I’ll also be reviewing and discussing Elly Griffiths’ intriguing mystery-thriller, THE CHALK PIT, which sees her female investigator, Dr Ruth Galloway, head into the tunnels underneath Norwich, where something truly odious may be going on.

As usual, you'll find the Elly Griffiths review at the lower end of today’s blogpost. But talking about Norwich and odious, I’m also moved today to muse a little on East Anglia, and the mythical horrors that may lurk amid its flat fields, gentle broads and deceptively pretty woodlands – particularly in regard to an anthology I edited, which was published several years ago, called TERROR TALES OF EAST ANGLIA .

But more about that later. First up, here’s the latest on the Lucy Clayburn front.

Missing without trace

Regular followers of this column will know that Lucy Clayburn is a young street-cop – a detective now, though she started out in uniform – in the fictional Crowley district of Manchester, and who, though she technically works divisional CID, frequently gets embroiled in much darker and more complex enquiries.

She’s appeared in two of my novels to date:

STRANGERS

in 2016, and

SHADOWS

in 2017, and will be hitting the bookshelves again in May next year.

She’s appeared in two of my novels to date:

STRANGERS

in 2016, and

SHADOWS

in 2017, and will be hitting the bookshelves again in May next year.Here, as promised, is the official blurb for the next book:

How do you find the missing when there’s no trail to follow?

DC Lucy Clayburn is having a tough time of it. Not only is her estranged father one of the North West’s toughest gangsters, but she is in the midst of one of the biggest police operations of her life.

Members of the public have started to disappear, taken from the streets as they’re going about their every day lives. But no bodies are appearing – it’s almost as if the victims never existed.

Lucy must chase a trail of dead ends and false starts as the disappearances mount up. But when her father gets caught in the crossfire, the investigation suddenly becomes a whole lot bloodier…

The Sunday Times bestseller returns with his latest nail-shredding thriller – a must for all fans of Happy Valley and M.J. Arlidge.

A cheerless realm

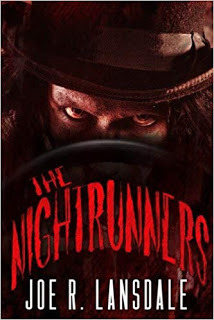

And now back to East Anglia. But before today’s Thrillers, Chillers section focusses on Norwich-set Gothic crime novel, THE CHALK PIT, I must talk a little about that anthology I edited back in 2012, TERROR TALES OF EAST ANGLIA .

This was the third volume in my round-the-UK antho series, which I started in 2011. The ethos of the Terror Tales books has always been to mingle local fact with local fiction, with a heavy emphasis on folklore – and of course to terrify readers out of their wits. (This has been the format throughout the series, and the format we’ll continue to use when, next year, my Terror Tales publishers, Telos Publishing, and I, will be going all out to get TERROR TALES OF NORTHWEST ENGLAND ready for an autumn release).

Before I say anything else about the East Anglian anthology (seven years old last September), please allow me to explain why I’m even thinking about it at the end of 2018.

Frankly … it’s because of the time of year.

Frankly … it’s because of the time of year.We’ve got some snow and ice forecast for next month, but at present Britain is a typical dreary scene: drab, leafless woods, grey, gloom-shrouded moorland, skies colourless and cold, any abandoned buildings, follies, disused bridges or railway tunnels, or other curious, unearthly structures standing desolate and alone in a landscape devoid of life.

Doesn’t that start to make you think MR James?

Whether it does or doesn’t, it always starts to make methink of the old ghost story master. Though, maybe this is as much the influence of the many television adaptations as it is the wonderfully frightening stories that he, himself, penned.

Because, though many of his eerie fictions were set at Christmas, or written to be read at Christmas, and in later decades became regarded as ‘Ghost Stories for Christmas’ (the famous BBC adaptations of the 1970s can now be bought together on DVD under that very title), they actually contain very few Christmassy elements. Oh yes, he frequently touches on the religious side of it – Midnight Mass, the Nine Lessons and Carols, etc – but the tales are quite spartan when it comes to festive trappings. We aren’t overly concerned with Christmas trees, or Yule logs, or wassailing, or even that staple of so many Christmas stories – snow.

Because, though many of his eerie fictions were set at Christmas, or written to be read at Christmas, and in later decades became regarded as ‘Ghost Stories for Christmas’ (the famous BBC adaptations of the 1970s can now be bought together on DVD under that very title), they actually contain very few Christmassy elements. Oh yes, he frequently touches on the religious side of it – Midnight Mass, the Nine Lessons and Carols, etc – but the tales are quite spartan when it comes to festive trappings. We aren’t overly concerned with Christmas trees, or Yule logs, or wassailing, or even that staple of so many Christmas stories – snow. So, though they are undoubtedly winter tales, they don’t always feel as if Christmas – at least, the Dickensian Christmas that we all know and love – is an essential ingredient, instead depicting the rural landscape of eastern England where so many of them are set (Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex), in the bleakest way imaginable. Okay, I know that’s not the whole story, but that’s very much my personal perception of the archetypal Jamesian backdrop, and that’s why, when we’ve finally worked our way through the festive bun-fight, and found ourselves with the bulk of the winter still stretching ahead, and especially if it’s as snowless and cheerless as this one, I inevitably find myself drawn to the writings of MR James and to the Jamesian school of horror writers.

Which brings me neatly back to

TERROR TALES OF EAST ANGLIA

.

Which brings me neatly back to

TERROR TALES OF EAST ANGLIA

.When I first commissioned a bunch of authors to send me some terrifying tales for this book, I didn’t specify that they needed to be written in the style of MR James, but almost inevitably, links were made, and a Jamesian tone generated.

Its back-cover blurb, which I wrote after selecting the stories, is perhaps a clearer indication of this:

East Anglia – a drear, flat land of fens and broads, lone gibbets and isolated cottages, where demon dogs howl in the night, witches and warlocks lurk at every crossroads, and corpse-candles burn in the marshland mist …

The giggling horror of Dagworth – The wandering torso of Happisburgh – The vile apparitions at Wicken – The slavering beast of Rendlesham – The faceless evil on Wallasea – The killer hounds of Southery – The dark guardian of Wandlebury ...

And so now, to celebrate this for no other reason than the weather being Jamesian and the mood very Jamesian (at least to me), I proudly present …

East Anglian terrors on film

Now, first of all, this is not a real thing. Not by any means. (Not yet, anyway).

But you may recall that, earlier this year, I decided to alter my regular Thrillers, Chillers, Shockers and Killers section by occasionally reviewing and discussing anthologies and single-author collections as well as novels, and each time, of course, selecting four particular stories from the book in question, which I’d love to see incorporated into a single movie, and giving them my usual fantasy cast.

Well … I’ve still got no anthologies ready to review at present, though plenty reside in my to-be-read pile. So, in the meantime, and just for a bit of a laugh, I’m keeping my hand in by doing it with the Terror Tales books. Obviously, I won’t be reviewing them as well, as that would be a bit incestuous (even though they are all brilliant), but at least I can turn each one into a portmanteau horror movie all of my own. You may recall that on May 16, we did it with TERROR TALES OF THE LAKE DISTRICT , and on July 4 with TERROR TALES OF CORNWALL. And so, totally keeping up with that theme, here is is …

TERROR TALES OF EAST ANGLIA – the movie

As I say, just a bit of fun. No film-maker has optioned this book yet, or any of the stories inside it, but here are my thoughts on how they should proceed. Note: these four stories are NOT the ones I necessarily consider to be the best in the book, but these are the four I perceive as most filmic and most right for a compendium horror. Of course, no such horror film can happen without a central thread, and this is where you guys, the audience, come in.

Just accept that four strangers have been thrown together in unusual circumstances which require them to relate spooky stories. It could be that they visit a series of sideshows in a run-down fair hosted by a mysterious, vaguely demonic showman, (remember Torture Garden?) or force entry to an eerie old wax museum, where each one of them finds his/her reflection in one of several ghastly effigies (Waxwork, anyone?) – but basically, it’s up to you.

Just accept that four strangers have been thrown together in unusual circumstances which require them to relate spooky stories. It could be that they visit a series of sideshows in a run-down fair hosted by a mysterious, vaguely demonic showman, (remember Torture Garden?) or force entry to an eerie old wax museum, where each one of them finds his/her reflection in one of several ghastly effigies (Waxwork, anyone?) – but basically, it’s up to you.So, without further ado, here are the stories and the casts I envisage performing in them:

The Watchman (by Roger Johnson)

Woolton Minster, a Norman church deep in rural Suffolk, is a nondescript religious building, not particularly handsome, nor especially rich, but it contains some precious vessels and boasts several horrific gargoyles, including one that stands almost ten feet in height. Thomas Drinkhall, a Scrooge-like local merchant, who has recently lost everything through misadventure, is unimpressed by this menacing figure, and as he carries a spare key to the church, resolves to rob the place. Night falls and Drinkhall secretly enters the ancient building, but it isn’t long before he starts to suspect that something else is there, something that moves with heavy, clumping feet …

Tomasina Drinkhall (for the sake of gender diversity) – Kathy Bates

Wicken Fen (by Paul Finch - sorry guys, but I’m never going to pass a chance to put my own work on film)

Middle-aged Londoners, Trevor and Gerry, take a weekend’s break away from their wives, hiring a narrow-boat on the Cambridgeshire broads, at the same time eyeing up girls and drinking lots of beer. But stresses soon emerge in their relationship, Gerry wanting to do more than just oggle the talent, and Trevor soon missing home. However, when they spy two young ladies who think nothing of sunbathing nude, even Trevor’s head is turned. He wants to stay loyal to his wife back home, but this nubile twosome are sexiness personified. Unfortunately, neither man has heard anything about the East Anglian myth of the terrifying mere-wives ...

Trevor English – Hugh GrantGerry Axewood – Jason Isaacs

Deep Water (by Christopher Harman)

Musician Peter Belloes might be having an affair with pretty young Elise, but when his wife, Celine, goes missing in their seaside hometown, he gets worried. Celine, a novelist who specialised in adapting East Anglian myths as children’s stories, was investigating the legend of the nightmarish Seagrim, which has clearly been a darker-than-usual project. The oddly odious Detective Sergeant Trench suspects that Celine drowned herself because of her husband’s infidelity, the Seagrim merely a metaphor for this. But Belloes isn’t even sure Celine is dead, especially when he starts to catch glimpses of her dripping-wet figure in various spots around town …

Peter Belloes – Colin FirthDetective Sergeant Trench – Timothy Spall

Wolferton Hall (by James Doig)

Medievalist, Hugh Terne, is given permission to occupy Throgmorton Hall in the wilds of Norfolk. There are plenty of documents to dig through, but a two-panelled fresco really catches his eye, depicting on one side the funeral of a murder victim and on the other a terrified man being chased by a skeleton. It creates an eerie atmosphere in the lonely manor house, as does the story that the Throgmorton family came into possession of the property after swindling it from a reputed sorcerer, who duly cursed the property. Is the curse still in force? And is there any truth in the rumour that it involves that infamous East Anglian demon, Black Shuck himself …

Julie Terne (again for the sake of gender diversity) – Nathalie Emmanuel

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE CHALK PIT

THE CHALK PIT by Elly Griffiths (2017)

Professor Ruth Galloway is Head of Forensic Archaeology at the University of North Norfolk. She also works regularly for the local Serious Crimes Unit (and its rugged, adversarial boss, DCI Harry Nelson) as a forensic investigator, but this is rural East Anglia, and as the largest nearby towns are Norwich and King’s Lynn, no one would expect Galloway to find herself on regular secondment to the police. However, that isn’t the case. Over the years, she’s had enough involvement in murder enquiries to consider the cops her colleagues, but on this occasion, it is Galloway herself who sets the ball rolling when she is summoned into the chalk workings underneath Norwich to examine some recently discovered bones.

Ordinarily, she’d expect these to be ancient and therefore of greater interest to the university than the local homicide team, only for her initial examination to show that not only are they relatively recent, but that they’ve been boiled clean – which might indicate that the unfortunate victim was cooked and eaten after he/she was killed.

This is hardly music to the ears of handsome architect Quentin Swan, who, though he is the one who called Galloway in, is looking to develop a subterranean shopping mall and food court, and now realises that he must put his obsessive dream on hold. Harry Nelson, meanwhile, is looking into the disappearance of a homeless woman called Babs. It isn’t a high priority, especially as other members of the local homeless community are proving unwilling to talk. But then he gets word – from an unreliable source, admittedly, but it’s unnerving nonetheless – that Babs has been ‘taken underground’.

No one really knows what this means, but further investigation uncovers rumours that a nameless group is dwelling in the labyrinthine passages beneath the city streets, not just the sewers, cellars and crypts, but in the same chalk workings that Ruth Galloway is investigating.

Galloway and Nelson are unsure what to make of this. It could be just a myth, but these stories won’t go away – and now there is the potential cannibal angle. Is it conceivable, as the scholarly Dr Martin Kellerman suggests, that some mysterious branch of the homeless community have not just become troglodytes, but are now hunting humans as food?

It’s almost too horrible to contemplate, but there are other sinister developments that seem to confirm this suspicion. Two of the homeless men who’ve admitted to knowing Babs and who seem to possess knowledge about what happened to her are found brutally murdered, one on the police station steps. In response, the whole machinery of the law swings into action, the division’s very correct Superintendent Jo Archer, determined that, at the very least, they have a serial killer on their patch who must be stopped.

Of course, fear that it may even be worse than that – namely that the killer is protecting a cannibal clan – preys on all their minds, and this is the kind of distraction that no one in The Chalk Pit needs. Because despite all outward appearances, this is quite a dysfunctional unit.

To start with, Galloway and Nelson once had a fling, during the course of which Galloway became pregnant and gave birth to a daughter. This is particularly awkward for Nelson, as he already has a wife, Michelle, who now knows about the affair and its illegitimate offspring, and resignedly accepts it, and two older legitimate daughters as well, who are still unaware that they have a half-sister. Nelson finds himself walking this tightrope every time he and Galloway work together, while his most able underlings – Detective Sergeants Judy Johnson and David ‘Cloughie’ Clough – are the opposite ends of the spectrum politically (Judy’s boyfriend, Michael ‘Cathbad’ Malone, is a practising druid while Cloughie likes beer and football!) and are often like fire and water with each other.

And then, as if all this means they haven’t already got enough to deal with, the stakes are raised dramatically, when a young, well-to-do mother vanishes from her own home, and once again rumours start circulating that she has been ‘taken underground’ …

My first thoughts on reading The Chalk Pit was that it doesn’t quite do what it says on the tin. It’s difficult to elaborate on that point without revealing too much of the synopsis. But I’ve said it now, so I’m going to have to offer some kind of explanation.

The blurb for this book provides us with a real hook:

Boiled human bones have been found in Norwich’s web of underground tunnels. When forensic archaeologist Dr Ruth Galloway discovers the bones aren’t as old as originally thought, it’s time for DCI Nelson to launch a murder inquiry. What was initially just a medieval curiosity has taken a much more sinister nature …

Local academic Martin Kellerman knows all about the tunnels and their history – but can his assertions of cannibalism and ritual killing possibly be true?

On this basis, it would be very easy to get stuck into this book expecting to find a cannibal tribe lurking under the streets of Norwich. But suffice to say that there isn’t anything like the blood and thunder this might lead you to anticipate.

Does that mean the book is disappointing?

Well … it all depends on what you were hoping for. Regular readers of the Dr Ruth Galloway mysteries, and The Chalk Pit comes ninth in that series, will know that they aren’t for the squeamish, but that there is still a degree of cosiness about them. They are solid procedurals, even though the main protagonist is not a copper. And the crimes that Galloway and her police allies investigate, while often grisly, are rarely OTT.

It’s true that the books often come wrapped in jackets adorned with Gothic imagery, which could easily make you think that we’re in supernatural territory. But we aren’t; Elly Griffiths writes crime fiction, not horror. But such imagery isn’t totally misplaced as her books bounce joyously around ancient borough towns like Norwich and King’s Lynn, which are rich in East Anglian history and can boast their fair share of dramatic and violent events – everything from Celtic resistance to the Romans, to Saxon resistance to the Normans, and on into the witch-hunting era (which saw one poor wretch not hanged or burned, but boiled alive!). All of this gives her novels a richly esoteric flavour, and The Chalk Pit is particularly good in this regard. It concerns itself with many contemporary issues, such as child protection, class distinction, homelessness, but there are also hints of the Grand Guignol, with much to do concerning medieval buildings like churches and guildhalls, and of course that eerie network of long-forgotten tunnels snaking beneath the city streets.

Galloway herself is an archaeologist, whose main interest is antiquity and for whom the discovery of a pile of human bones is usually a source of delight rather than despair. Then there are characters like Cathbad, who harks back to the beliefs of those eldritch days predating Christianity. Oh yes, The Chalk Pit , like all of Elly Griffiths’ work, is rammed with local colour and local lore. Just don’t expect it to be gory or terrifying.

That said, the novel’s criminal investigation is deeply intriguing, and a genuine page-turner, particularly after Cloughie’s girlfriend, Cassandra, is kidnapped. I reckon I flew through the final third of the book. But at least half the jeopardy in this narrative doesn’t stem from the police enquiry, so much as from the tense relationships between characters.

This is particularly effective where Galloway and Nelson are concerned, their unrequited love providing the book’s emotional core. The irony here, of course, is that Galloway is a very modern woman. Independent-minded and successful, she doesn’t need a man in her life, but she wants Nelson. He, already married and with two grown-up daughters, is equally tortured, because while he loves Galloway, he dotes on his existing family too. And it’s all nicely understated. There are no outbursts here, no hysterical tears. The duo just gets on with it, working together quietly in that staid, stiff-upper-lip British way, but secretly enjoying the contacts they have with each other.

The rest of the cops – and The Chalk Pit is very much an ensemble piece, rather than exclusively a ‘Ruth Galloway adventure’ – are instantly recognisable as the sort of people you’d meet in any real-life police station.

Judy Johnson, another modern female, is confident, terse, leaning a little towards authoritarianism, and yet somehow just right for the off-the-wall man in her life, Cathbad. Then there is Cloughie, who is much more ‘old school’, and yet whose working-class origins ensure that he gets a rapport going with the many homeless characters they encounter. (On the subject of the homeless, and there are plenty in this book, I feel the author delivers an idealised picture of them. While they are all clearly damaged, few appear deeply troubled, instead spreading good will and happiness wherever they go – which I’m sorry to say I didn’t buy).

That only leaves us with the villains, though I don’t want to talk too much about them for fear of giving vital stuff away. But put it this way: we have an entire array of suspects by the end of this book. They’re all totally believable – none are slotted in as obvious red herrings, and all emerge under their own steam, Griffiths gradually persuading us without actually needing to say it that any one of them could be the killer.

But no more about that now; as I say, no further spoilers here.

Like all good novels, The Chalk Pit is not just about what’s happening on the surface. All through the book there is an interesting if subliminal discussion about the absence of faith in the modern day. Quite a few of the characters are hostile to religion, but as the case progresses, more and more are drawn to reminisce about their religious upbringing when they were young, and while there isn’t any obvious regret that it’s all gone, some of them start to recognise an emptiness in their lives, and increasingly as they suspect they’re up against a horrific evil, they feel less and less equipped to deal with it. It didn’t escape my notice that two of the most contented characters in the book are Cathbad, the druid, and Paul Pritchard, the born again ex-bank robber. And it won’t go unnoticed by anyone that, towards the end of the book, two characters who previously were planning to get hitched in a registry office, change their plans and opt for a church wedding instead.

The Chalk Pit is a great example of a fast, multi-layered (literally) and very well-written British police thriller, the sort you could easily imagine being put on television. A straightforward murder case, but believably presented and built around characters you care about. As long as you aren’t led by the blurb to expect gaudy displays of Dark Ages carnage, you should enjoy this one thoroughly.

As usual now, in the event that Ruth Galloway does end up on TV sometime, I’m going to try and pre-empt everyone by nominating my own cast. Just a bit of fun of course, but here are my picks for who ought to play the leads should The Chalk Pit ever make it to the screen:

Dr Ruth Galloway – Emily WatsonDCI Harry Nelson – Christopher EcclestonMichelle Nelson – Jessica HynesDS Judy Johnson – Katie McGrathMichael ‘Cathbad’ Malone – Kevin DoyleSupt. Jo Archer – Helen BaxendaleDS David Clough – Kevin Fletcher Cassandra Blackstock – Sophia Jayne MylesQuentin Swan – Jason HughesPaul Pritchard – Patrick Baladi Dr David Kellerman – Jeff Rawle

Published on December 29, 2018 06:29

December 6, 2018

Old evils wake in the dark depths of winter

Well, it’s a week into December, which means that Christmas is finally looming large on the horizon. So, we’re now well into the winter ghost and horror season, and that means we literally have no option but to continue in that chilling (pun intended) vein.

This week, for the benefit of recent readers, I’m going to resurrect memories of and post free, direct links to the plethora of Christmas spook stories I’ve written in recent years and attached to this blog. I’ll also be seeking to push a few Yuletide terror addicts towards my Christmas ghost story collection, IN A DEEP, DARK DECEMBER, which was first published as an e-book in 2014 (though it also appeared the following year in Germany, as a paperback).

And if that’s not enough for you fans of this most atmospheric part of the scary story calendar, I’ll be reviewing and discussing in some considerable detail Ramsey Campbell’s masterly, winter-set horror novel, THE GRIN OF THE DARK.

If you’re mainly here for the Campbell review, that’s perfectly fine. You’ll find it, as always, at the lower end of today’s blogpost. However, if you’ve got a bit more time on your hands, let me talk a little bit first about some of my own festive horror output.

Spirits of the season

Each year for the last – tell the truth, I’m not sure how many – I’ve celebrated December by posting a new Christmas ghost story on this blog, entirely free to read. It’s my intention to do the same this year, so in the next few weeks keep checking in, and at some point you’ll find my latest contribution to this season’s fearsome frolics.

However, just in case you’re impatient for some immediate festive ghost/horror action – and especially if you’re relatively new to this blog, here are some links to past stories, with a brief snippet in each case to whet your appetite. Feel free to check ’em out at your leisure – just be advised that the first one, Brightly Shone the Moon That Night is a thriller rather than a supernatural horror, but I’m reliably informed that most horror fans have enjoyed it thus far).

BRIGHTLY SHONE THE MOON THAT NIGHT

BRIGHTLY SHONE THE MOON THAT NIGHTPart One, Part Two, Part Three

Heck is the only cop on duty one very cold Christmas Eve when a trio of deranged carol singers goes house to house, leaving a trail of bloody carnage …

Jen turned the lock and opened up the narrowest of narrow gaps. It was an enormous surprise to see how close the singer was actually standing. He was virtually on the step, his face no more than ten inches from her own. ‘Ahhh … good evening, my dear,’ he said, breaking off from his song. The immediate odour was of halitosis, followed promptly by stale sweat and nicotine. His garb, though reminiscent of a hundred adaptations of Scrooge – a double-caped greatcoat and muffler, a cravat and a high collar, a tilted topper and Faginesque fingerless gloves – was worn and moth-eaten, a pantomime costume purloined from some forgotten cellar. His face was pudgy and discoloured, with overgrown side-whiskers, brownish teeth, and a left eye milky and rolling independently in its narrowed, unblinking socket. Even then, she thought, in some vague way, a wholesomeness might lurk there – that lovely baritone voice! – or might have lurked there once even if now long departed. ‘And a merry Christmas to you,’ he said, in a voice rich and resonant. It bespoke education and breeding rather than the hardscrabble streets of the East End, which seemed to fit with the impression she had of a gentleman gone to seed. She observed the twosome with him. They stood to his rear, one partly behind the other. The furthest away loitered in the gap between the gateposts. Despite the deluge of snowflakes, which continued to obscure much, this was clearly a woman. Not especially tall, about five-foot-six – a little shorter than Jen – but also done up in shabby Victorian garb, and clutching a bundle of rags as though it was a baby. She wore a coal-scuttle bonnet and a drab, floor-length dress, much patched, and was huddled into a ragged shawl. The bonnet completely concealed her face because, all the time Jen watched her, the woman stood with head drooped, motionless even as the flakes gathered on her wool-clad shoulders. The second of the visitors, the one immediately behind the soloist, was much more alarming. From his size and shape, he was clearly male, and he wore a parti-coloured red and green suit, like a harlequin costume, but this too was baggy and threadbare. On his head, there was a red coxcomb hat, which rose to several peaks, all dangling with bells; underneath that, his face was concealed behind a protruding papier-mâché mask, a basic, crudely-made thing whose exaggeratedly moulded and painted features – the axe-blade nose in particular, and the jutting, knifelike chin – denoted the malign visage of Mr Punch. Though perhaps the most disturbing feature of this particular character was the eyes. They were nothing but empty holes, and though real eyes undoubtedly lay behind them, at present they were pits of inscrutable blackness …

THE UNREAL

A ghost-hunting sceptic and devout Christmas-hater opts to spend Christmas Eve alone in a notoriously haunted theatre, midway through the production of A Christmas Carol …

“I have to say, I’ve never really thought the Ambridge haunted myself, and I’ve been a member over forty years. There are no specific stories; it’s just an eerie old building I guess. If there’s any spirit here at present …” Lampwick glanced at the lobby’s festive brocade, “… I’d say it was the spirit of the season. Not that this is always a good thing.” “It isn’t?” Hetherington asked, puzzled by that. “Well, they say Christmas is what you make it … that you get the Christmas you deserve, and all that.” “Good job I don’t do Christmas.” Lampwick headed to the fire-door, muttering something in response that sounded like “Let’s hope it doesn’t do you.” “I’m sorry?” Hetherington asked. “Missed that.” Lampwick opened the door, and a waft of icy air blew in. “I said good luck to you.” “Okay … thanks.” “One last thing,” Lampwick said. “When are you planning on leaving tomorrow?” “First light … half past eight, nine-ish.” “If you throw the breakers back on first, and whichever door you leave through, make sure you close it after you. I’ll be popping in mid-morning on my way to my daughter’s for Christmas lunch, to check everything’s okay. And I’ll put the alarms back on.” Lampwick halted in the doorway. “You’re absolutely sure you want to do this?” Here we go again. “I’m sure. And thanks for your concern, but I’ve done it many times before.” “Not here.” “No, not here,” Hetherington agreed. “But then you don’t believe this place is haunted either.” “No, but then I’ve never stayed here overnight, not on my own.” In the dark, when there’s nobody else here … eh, Mr Lampwick? Lampwick smiled, again as if he’d just read Hetherington’s inner thoughts. Then he departed into the blackness and the snow, shutting the fire-exit door behind him …

KRAMPUS

KRAMPUS

In the deprived years after the close of World War Two, a German child living in Britain is terrorised by nightmarish Nazi version of Father Christmas …

The street we had just walked along was lined down either side with terraced houses; a perfectly normal street in our part of the world, yet now an increasingly stiff breeze was whipping the snow in eddies – on some occasions I could see as far along it as the coal wagon parked at its distant end, on others no more than thirty yards. I remained there for several minutes, convinced there’d be something to fix on if only I could gaze into the murk hard enough. Intermittently down that street, curtains were only half-drawn, thus allowing rays of soft, warm lamplight to penetrate outward. Without warning, someone passed one of these. I blinked – and they’d gone again, hidden by renewed swirls of flakes. But it was someone headed in my direction. Someone wearing red. It could have been any ordinary person walking home; there was absolutely no need to assume the worst. But briefly I was rooted in place. Only slowly, with great difficulty, was I able to retreat to the edge of the pavement, where again I waited. I don’t know why; it makes no sense now – it was as if I had some inner urgent need to know I was in danger rather than simply fear it. But then something happened that leant genuine panic to my heels. I spied the figure again, much closer this time – maybe forty yards away – crossing the street to the side on which I was waiting. It was only a silhouette, half-glimpsed as it passed through another shaft of flake-speckled lamplight, but it was bent forward in ungainly fashion, its back humped, its heavy robes trailing behind it. There was no further debate in my mind. I spun around and raced blindly along the next street, and along the one after that, regardless of the treacherous footing. I must have covered half the distance home before I stopped to get my breath. I had seen no-one else that whole way, but likewise no-one was in sight behind me either, and now, the flakes having relented a little, I was able to see a good distance in every direction – and spied nothing but snow-covered road junctions, the red-brick gable walls of houses, the weak palls of light cast by streetlamps. Nothing advanced through them, so I felt a little better, though I had yet to cross Dalewood Brow. That place no longer exists today – a supermarket and offices have been built there instead, but in my childhood, it consisted of several hundred yards of derelict colliery land, hummocky and deeply overgrown; a wonderful place for children to play in summer, but in wintry darkness a test of anyone’s nerve …

MIDNIGHT SERVICE

A disillusioned college lecturer spends Christmas Eve marooned in a mysterious and semi-deserted town, where the celebrations are the eeriest he’s ever known …

The bigger problem at present was the cold. Never having expected to be outdoors, he was only wearing a lightweight jacket over his shirt. His trainers were already caked with ice crystals, which were fast melting through the rubber and canvas, soaking his socks and feet. It was pure good fortune that he had gloves, but they weren’t much protection in truth. He’d wandered for quite some time by now, and probably wouldn’t even be able to find his way back to the coach station. He glanced around, feeling more than a little concerned, but no fellow pedestrians were abroad to ask. The steadily falling snow muffled all sound, so even if there’d been someone on a nearby street, he wouldn’t necessarily hear them. The occasional car swished by, but they were few and far between. Capstick walked on, entering a small square, on the other side of which stood a row of spike-topped railings with an open gate in the middle, giving through to what looked like a yard enclosed by high buildings, though down at the far end of it a light was moving. It was only a glimmer; from this distance it looked like someone carrying a lantern. As Capstick watched, the clotted blackness down there split vertically as more light spilled through an opened door, widened further to admit the outline of a figure, then narrowed again and winked out. A faint thump was heard. He approached the railings and peered across the yard. The building at the far end looked vaguely churchlike. It was too dark to see any real detail, but its roof was vaulted and there was a spire of some sort. Before he knew what he was doing, he was walking down towards it. Capstick hadn’t been into a church for as long as he could remember and had no religious beliefs. In fact, there was a time when he’d badmouthed Christianity at every opportunity, calling it “abusive superstition” and preferring to ignore the good things it did, such as the provision of charity and shelter. Not that he was going to ask for either of those things now – good God, he wasn’t that far gone! – but he could use some directions, and it wouldn’t hurt to go indoors and get warm for a few minutes. A high stained-glass window on the right implied he was correct about the ecclesiastical purpose of this place, though there was no light behind it, making it look grimy, while several of its panes appeared to be missing. On the left, he passed what looked like a small memorial garden recessed between cliff-faces of brickwork. A central statue grinned at him from beneath a veil of icicles. One stone hand clutched an upright spear; the other extended forward, also covered in snow, but pointing downward. When he reached the main entrance door, he saw a slogan painted in black on the whitewashed bricks above its lintel:

GOD IS JUST

A CHRISTMAS YET TO COME

A CHRISTMAS YET TO COME

A neglectful son lets his aged father die one desolate Christmas Eve and thinks he’s unloaded a burden. But as Christmas comes around again his nervousness grows …

Mike went back to bed, still feeling weak. Chrissie wouldn’t be back from work until five – not that this was anything to look forward to. She found it trying, having an invalid in the house, and did nothing to hide it. That was when he heard the sleigh bells. He sat up from the pillow and looked slowly round at the window. It was open, and beyond it he saw the azure sky of late summer, the rich green leaves on the trees opposite. He heard children playing – still on holiday from school; the sound of someone mowing their lawn. He smelled chopped grass and barbecue coals being stoked up for another glorious evening. Yet sleigh-bells were approaching gaily, along with crisp, clip-clopping hooves. They came to a halt right under his bedroom window. Mike felt his hair prickling but was unable to move to look. The children were still playing, the lawnmower still revving over the turf. At any second, he expected a hearty knock at the door. But the next thing he heard was a foot on the stair. Then another. Stealthy, padding footfalls – as though someone was coming up uncertainly, or painfully. A silvery bell tingled. Mike imagined that shabby, stumbling Father Christmas – holding out a little Yuletide bell, ringing it before him to bring in custom, just like one of those old men paid to stand outside department stores in December. The footsteps were now on the landing, the tingling bell right outside Mike’s bedroom door. It was not closed properly, and someone slowly pushed it open ... Then Mrs. Barnard from next door walked in. When she saw that he was awake she looked relieved. She hadn’t wanted to disturb him, she said. But she felt she had to return the house-keys Chrissie had given her while they’d been away on holiday last July. She held them up in a bunch, and they tingled together – just like bells. Mike swore hysterically at her for nearly a full minute before she turned and fled in rivers of tears. When Chrissie returned from work that evening, she was ambushed by the distraught woman before she could even get into the house, and finally came upstairs in a vexed mood. Mike was still lying in bed, and his wife gave him a good four minutes of her time before she even began to get changed. It was no use him taking things out on her and the neighbours! Just because he wasn’t feeling so good! They had cause to get annoyed with him if they felt like it! But by the time she’d finished, Mike was no longer listening. He was too busy staring out through the bedroom door at the scattered white globules on the landing carpet. They steadily dissipated as he watched them. It was the sort of thing you saw in deepest winter, when somebody had come in with snowy boots on.

THE TRUSTY SERVANT

THE TRUSTY SERVANT

Office-worker, Wilton, is increasingly disturbed as the Roman temple in the nearby church crypt is excavated. It’s almost Christmas, and the feast of Saturnalia is looming …

It was early afternoon and he was working in his office, when he heard a step on the landing beyond the door. He glanced up sharply. Dowerby and his partner were both away on business, and their secretaries were on Christmas leave, so Wilton should have been the only person in the building. Before he knew what he was doing, he was reaching for the telephone. What happened next, however, practically paralysed him. The handle on the door to his office began to turn. But only slowly. Furtively. Wilton felt sweat break on his brow as he watched. His blood went cold. There was a grunt on the other side of the door, as though whoever was there could not manage to open it. The handle stopped turning and there was a brief silence. Then, the wooden panelling of the door began to creak from some weight being applied to it. Wilton’s spine was literally crawling. He found his fingers fumbling with the dial on the telephone. For ludicrous seconds, he couldn’t remember the emergency code. Then the intruder seemed to move away. Wilton listened to soft but heavy feet, as they padded up the next flight of stairs. He stood up, his heart pounding. The whole demeanour of whoever this person was gave him away as a burglar. The outer doors to the Society Chambers were not locked during the day, but a visit like this was not bona fide. Wilton didn’t know what valuables Dowerby and his partner kept in their offices upstairs, but the intruder was clearly on his way to find out. Without hesitation, Wilton called the police. They said they would send someone immediately, but minutes seem to pass and eventually Wilton began to fear that the burglar would leave the premises before they arrived, or even worse try to get into his office again. It was now very quiet upstairs. Wilton strained his ear as he listened against his door. It occurred to him that he was behaving in a rather cowardly fashion. This might be the thing for a young female secretary to do – call for help and then hide. But would he, as a male, not at least be expected to make some approach to the intruder? What would his employers think if he just let the villain walk away again before the police even arrived? After a minute of agonised indecision, he stuck his head out through the door. The landing was deserted. That was to be expected, whoever it was having gone upstairs. Wilton followed stealthily, praying for the sound of an approaching siren. At the top of the next flight, there was still no sign of anybody, but the door to Dowerby’s office stood ajar. It could have been left that way, but it seemed unlikely. Swallowing hard, Wilton advanced towards it. When he pushed it, it swung open. He entered. There was nobody in there. Wilton was now baffled. He had heard somebody coming up here, hadn’t he? He turned to leave – and found his way barred by a hulking man with mad, staring eyes and a gross beard filled with crawling lice.

SNOW JOKE

SNOW JOKE

An evil-looking snowman and a book of spells are all that young Jimmy needs to punish his thoughtless dad, but once the means of vengeance is loose, will anyone be safe? …

Charlotte wasn’t coming home this Christmas. She spent most of her time at a place called the LSE, but now apparently, was somewhere called Kathmandu and had recently written to her parents, saying that she considered the yuletide feast a corrupt, western opiate and no longer had any time for it. Mum had cried, and Dad had gone mad, storming around the house shouting something about “the weed” finally getting to “her great, stupid, empty head!” Jimmy hadn’t got cross with Dad on that occasion because both he and Mum, for once, had seemed to be in agreement on it. But it didn’t make any difference: Charlotte was still away for Christmas and would see them some time in the New Year. Once Jimmy had got used to the idea, it hadn’t bothered him too much because it meant that he could spend the first few days of his school holidays digging around among the various odds and ends in her room. That was when he’d found the Tome of Lore. The treasure trove of odd-smelling bric-a-brac in Charlotte’s room, stuffed under her bed, littering her desk and dressing table, had proved a novel distraction at first, but not as much as this particular book, which as well as being full of mucky drawings, also had gross but neat pictures of goats’ heads on tables, half-men-half-monster things, people on crosses upside-down, and animals with unreadable names scrawled underneath them. Jimmy was a bright lad and it hadn’t taken him long to work out what it was all about. He vaguely remembered Dad once having a row with Charlotte over the “voodoo crap” he’d found on the toilet shelf when he’d been looking for his football yearbook. The thing was, Jimmy hadn’t believed that any of it was for real – not until soon after lunch, when he’d gone out into the back garden again and found the snowman missing …

If all that leaves you wanting more, don’t forget that my Christmas e-collection of 2014,

If all that leaves you wanting more, don’t forget that my Christmas e-collection of 2014,IN A DEEP, DARK DECEMBER , is still available for purchase. As I mentioned earlier, German readers can acquire it in paperback if they so wish. Just follow DAS GESPENST VON KILLINGLY HALL .

In case you need any more persuading, here is a quick thumbnail outline for each of the five stories contained inside.

THE CHRISTMAS TOYS: Two burglars target an ordinary suburban house one Christmas Eve, only to awaken the dark side of the festive spirit …

MIDNIGHT SERVICE: A stranded traveller in a desolate town one snowy Christmas Eve. Where can he find shelter? The former workhouse, of course …

THE FAERIE: Timid husband Arthur snatches his young daughter and flees his angry wife across the wintry moors, finally seeking sanctuary in a mysterious snowbound house …

THE MUMMERS: Two men plot an elaborate Christmas Eve revenge by summoning a pantomime from Hell …

THE KILLING GROUND: During an atmospheric English Christmas, man and wife security experts are hired to protect a film star’s family from the cannibal woman said to haunt their new country estate … (Be advised that The Killing Ground is a novella, so if you decide to cough up the 99p price tag, you’re still getting quit a bit of wordage for you money).

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE GRIN OF THE DARK

THE GRIN OF THE DARK by Ramsey Campbell (2007)

London-based northerner, Simon Lester, feels that he’s on the verge of making a breakthrough in his chosen career of film journalism.

He almost managed it once before when he found himself working for the controversial movie magazine, Cineassed – though all of that went belly-up when Simon and his reckless editor, Colin Vernon, got the mag sued for libel. Since then, Simon’s been employed at a petrol station, with nothing to offer his pragmatic fiancée, Natalie Halloran, other than vague guarantees that all will be well eventually.

But yes … now, at last, it seems to have happened.

High-flying academic, and former tutor of Simon’s, Rufus Wall, offers him a commission to write a film studies textbook for London University’s new line, with a £10,000 advance. Simon finally thinks that he’s arrived, but not everyone shares this viewpoint. Natalie will only believe that her beloved’s career is back on track when she sees it, while her parents – Warren and Bebe, who also happen to be Simon’s landlords – remain steadfastly unimpressed, thinking that Simon should get a proper job, and wishing that their daughter was back with her ex, the smooth and moneyed Nicholas (who also happens to be father to her lively young son, Mark).

Of course, Simon, agog with excitement that someone will finally pay him to do what he loves, brushes all this aside in his quest to find a suitable topic for the new book, settling on the career of one Tubby Thackeray, a British music hall clown turned Hollywood silent era comedian, who eventually was blacklisted because his brand of slapstick was so demented that public order situations arose whenever he appeared (some viewers were even said to have lost their minds).

It isn’t perhaps the wisest choice, because Tubby Thackeray really has been expunged from movie history. Encouraged by young Mark, who catches a snippet of Tubby in action and falls in love with the silent era legend – to an inordinate degree, it seems to us, though Simon, typically, doesn’t notice this – he commences his research, but finds it more of a challenge than he expected. Those who allegedly know about Tubby seem reluctant to talk, and the few bits of written information he can find are located at obscure, antiquarian-type events, where he has to leaf through piles of dead newspapers and deal with increasingly strange personalities.

And that’s another thing about this affair … the strangeness.

From the moment, Simon starts looking into Tubby Thackeray, curious events occur. Any useful intel he finds on the internet seems to change from one viewing to the next. He constantly hears deranged cackling from behind apartment doors or on the other sides of bookstacks. In the corners of his vision, he glimpses creepy, grinning, clown-like men, who seem to find his every move – and especially his mistakes – hilarious. When he finally locates some real footage of Tubby, he thinks it radical and inventive for the time, but also dark and disturbing. Was Thackeray really doing comedy, or something much more sinister?

Meanwhile, there are other distractions. Bebe and Warren Halloran are a constant source of discouragement, while the insufferable Nicholas seems to be showing up ever more regularly, which threatens Simon’s relationship with Mark, though even more so his relationship with Natalie, who is turning progressively cooler with him. It’s also an unpleasant development when Rufus Wall foists a new editor on him – Colin Vernon, of Cineassednotoriety – while Simon also makes the mistake of engaging in a chat-room debate with an anonymous but self-proclaimed expert on the silent comedy greats, who goes by the nickname Smilemime. It’s a futile exercise, but Simon finds himself getting drawn in, wasting more and more time arguing with someone he doesn’t even know, and yet who increasingly appears to know him.

At the same time, the people he meets in real life are no less easy to deal with.

Bolshy Manchester man, Charlie Tracy, appears well informed about Tubby Thackeray, but is an awkward and suspicious individual, who no one would want to rely on unless they had to. And when Simon heads to California, to interview Wilhelmina, the granddaughter of Orville Hart, who directed some of Tubby’s movies, he finds her a coked-out porn queen, whose ranch-like home is populated by nubile females of a distinctly weird and predatory nature (and who – and this is Simon’s real concern, given that Natalie is waiting at home – enjoy putting all their conquests on the internet!).

All this time, meanwhile, Christmas is coming, and Simon feels that a visit home may be necessary, especially when he learns that his native Preston, in Lancashire, once played host to a famous music hall incident, when Tubby Thackery roused the crowd to much more than laughter. But Simon’s home has a cloying atmosphere all of its own, his mother in the early stages of senility and his father unable to cope, while the derelict theatre where they eventually take him is a horror story in its own right.

And all the while, that background strangeness intensifies, the hapless Simon shifting through altered states as he determinedly tries to ignore the phantoms dogging him during his quest to fully expose Tubby Thackeray, a comic genius and an apparent prince of chaos …

A warning from the outset: if you like your horror stories cruel, garish and filled with blood and violence, then don’t bother with The Grin of the Dark . However, if you’re a cerebral scare fan, and you don’t mind a slow-burn atmosphere, you can’t really afford to miss this one.

Not that Campbell is overly subtle. Make no mistake, there is a real horror at the heart of this tale, and it leaks out through the pores as you work your way along. Much of it is intensely psychological, even though there is no question that we are dealing with supernatural forces, and malevolent ones at that. Simon Lester’s mental disintegration is unrelenting, taking us into a surrealist netherworld of obsession and paranoia, where his seemingly harmless quest to research a long-forgotten comedian doesn’t just see him encounter hostility at every turn, much of it disturbingly irrational, but literally awakens demons.

In many ways, The Grin of the Dark is vintage Ramsey Campbell. We’re in a bleak urban environment where, even though we flit back and forth between London and Northwest England, everything is faded and decayed, which is populated by jobsworths and functionaries so unhelpful as to be almost obstructive, and yet, only thinly disguised by this aura of the depressingly mundane, we sense constant, simmering evil, a near-Lovecraftian presence of the bizarre, which we regularly glimpse – or think we glimpse, because, in classic Campbell style, we can never be absolutely sure.

Simon Lester himself is a typical Campbell hero: an essentially well-meaning guy, a workaday everyman, a little introverted and intellectually absorbed, whose pursuits are innocent if niche, but at the same time someone who doesn’t connect easily with others and is therefore mistrusted (and who, on occasion, needs to man up in his confrontations). But he has a good relationship with Mark, his stepson-to-be, while the strong and personable Natalie has seen something in him that she wants to marry, so we are firmly in ‘good guy’ territory. On top of that, you can’t help but root for the bloke when he encounters so much opposition. His soon-to-be in-laws, Warren and Bebe, for example, are frankly hateful, so hostile to their daughter’s choice of boyfriend, so belittling of almost everything he does that it’s no wonder he appears to lack confidence.

We’re also in traditional Campbell country in terms of several classy horror set-pieces.

It’s an absolute staple of this author’s fiction that low-key creepiness will abound, and The Grin of the Dark is completely true to that. But in addition to these lesser but ongoing tortures, we are also plunged into some epic scare situations, including a head-trip sequence in a run-down circus in the heart of wintry London, and most terrifyingly of all – and this scene is Ramsey Campbell at his very best! – an exploration of the derelict Preston theatre, where a sense of fear is palpable from the moment the investigators force entry, but soon becomes utterly overwhelming.

Ramsey Campbell is not regarded as ‘Britain’s Greatest Living Horror Writer’ for nothing, of course. And even in other scenes, where the terror isn’t as full-on, the air of menace stems from an increasing dislocation of reality. For example, a straightforward presentation that Simon makes to a Tubby Thackeray fan-club becomes a nightmarish ordeal. Likewise, his journey to California to interview the hedonistic Wilhemina Hart, which seems to crash head-on into a follow-up trip to Amsterdam, is a triumph of drug and porn-induced disorientation.

Campbell also makes excellent use of a very new kind of monster, the internet troll.

Simon Lester’s ongoing duel with the creepy madman, Smilemime, which he gets into initially for the right reasons because he’s trying to learn everything he can about the elusive Tubby, soon becomes a hellish narrative in its own right. Not every reviewer has favoured this aspect of the novel, calling it unnecessary and protracted, but for me it works perfectly. The smugly arrogant Smilemime is only one facet of the malignancy Simon seems to have disturbed, and it’s a very potent one. This part of the book also serves as a sobering lesson to the rest of us about the futility of engaging online with shallow, nameless narcissists who may demonstrate countless shortcomings – spelling, grammar, etc – and yet who will always win because they are content to spend all day/week/month (as long as it takes) doing nothing other than trying to get the better of their perceived opponents.

All through the book, of course, and this is perhaps the real success of The Grin of the Dark , the evil Tubby lurks close by, constantly on the verge of breaking loose – even though he only physically appears in snippets of crackly film or sepia-toned newspapers. Needless to say, on those few occasions when we do see him, he is a demon lord, seeming to combine every strange and menacing aspect of those heavily made-up, wildly gesticulating comics of the gaslight age, performing antics so outlandish that you can easily imagine it having a damaging effect on audiences not used to such onscreen anarchy.

I should add that not all reviews of The Grin of the Dark have been hugely positive. Ramsey Campbell has a unique style. He conceals clues which, if you miss them the first time around, may mean that you have to roll back a few chapters to check again. Certain readers haven’t appreciated this, though I think it’s an acceptable and clever device. Likewise, others have expressed impatience with the clown factor, calling it a cliché, and indeed there are clowns aplenty in this book, not just Tubby himself, though – and I stress this – these are no axe-wielding maniac clowns of the modern-day slasher variety. All their manifestations are connected to that golden age of comedy, and, once again, to those extreme and harrowing lengths so many silent era practitioners went to in order to immortalise themselves.

At the end of the day, in an age when horror suffers almost permanently from bad press – so many writing it off as gory, derivative nastiness, Ramsey Campbell is still one of the genre’s great breaths of fresh air. A skilled and intelligent writer, he has the ability to lay out deep, macabre mysteries and to invoke genuine chills from the most everyday situations, plucking at nerves we scarcely knew we had, all the while shedding barely a drop of blood.

The Grin of the Dark is a great example of this, recounting a complex but genuinely frightening tale and setting it in a world that closely resembles ours and yet is increasingly and distressingly off-kilter. If you’re a horror fan and you haven’t yet read this one, you really need to.

It’s one of the great puzzles to me that Ramsey Campbell’s work – and it constitutes a vast body – has never (to my knowledge) received any kind of film or TV treatment. I’ve constantly told myself that some kind of adaptation must only be around the corner. His short stories in particular scream to occupy a ‘Christmas chiller’ slot, but in the absence of that, for the moment at least, we can only fantasise – which is what I’m going to do now. Here, as usual at the end of one of my reviews, is a personal take on who should make up the cast-list should The Grin of the Dark ever hit the screen.

Simon Lester – Jack O’ConnellNatalie Halloran – Ellen PageWarren Halloran – Gabriel ByrneBebe Halloran – Veronica CartwrightCharlie Tracy – Stephen GrahamRufus Wall – Dexter FletcherColin Vernon – Chris O’DowdWilhelmina Hart – Jennifer Love HewittTubby Thackeray – Bill Skarsgård

Published on December 06, 2018 04:56

November 15, 2018

Lucy Clayburn may soon be on the screen

I want to talk a little bit today about my recent change of publisher, and what this will mean for my fictional characters. At the same time, I have some rather exciting, and not unconnected news concerning one of those characters – Lucy Clayburn. And yes, before anyone queries today’s headline, it does involve a potential film/television adaptation.

I want to talk a little bit today about my recent change of publisher, and what this will mean for my fictional characters. At the same time, I have some rather exciting, and not unconnected news concerning one of those characters – Lucy Clayburn. And yes, before anyone queries today’s headline, it does involve a potential film/television adaptation.On a similar subject – novels that certainly should be hitting our screens, even if at present there are no plans for that (and in this particular case I don’t know whether there are or aren’t) – I’ll be discussing Peter James’ new, globe-trotting thriller, ABSOLUTE TRUTH, and reviewing it in my usual forensic detail.

This latest Peter James novel has already caused something of a stir, thanks mainly to its astonishing central premise, but if you want to read more about that, as usual you’ll need to venture down to the lower end of today’s blogpost. Be my guest and do it now, if you wish. But if you’ve got a bit more time, you might want to stick around a little longer and hear what I have to say about my own writing plans and the all-new developments where Lucy Clayburn is concerned.

Change is inevitable

I’m not going to harp on about this too much, because while it’s very important to me, it probably won’t matter a lot to you readers out there. But I thought I might as well mention it on my blog just to ensure that the facts are on record.

I’ve now been a novelist with Avon Books, at HarperCollins, since 2013, and when SAVAGES is published in April next year, it will be the tenth book I’ve written under that imprint.

So, it’s certainly been a busy time at Avon, but it’s also been an incredible one, and a life-changing experience in so many ways.

All along, I’ve been guided by expert editors, specifically Helen Huthwaite, who’s managed to turn me from a roguish reveller in dark fiction ranging widely across the interconnected fields of horror, fantasy, sci-fi and thriller, into a disciplined and focussed crime-fiction specialist, and has teased out of me some of my best characters and most nightmarish scenarios.

I can’t thank Avon enough, and Helen in particular, for recognising my potential and turning me into an official best-selling author.

So why, you may ask, am I moving on?

Well, it’s never a simple thing. It’s not as if I’ve fallen out with anyone or felt that I’m being restricted. It’s just that a change of scene is always good, especially when you’ve been in the same place for rather a long time. And when an outfit like Orion Publishing come calling, you have to take them very seriously indeed.

So, after a few meetings between all concerned, including a couple of particularly exciting editorial sessions, a decision was reached, and an amicable parting of the ways agreed between myself and Avon. It’s not as if they’re short of great writers anyway. Check out Cally Taylor, Scott Mariani, Helen Fields, Jacqui Rose, Mel Sherratt, etc.

But all that aside, I’ve still got one book to bring out under the Avon imprint, and I’m working on it with my editor as we speak.

It’s called SAVAGES – at least, that’s the title so far (it could still change) – it pits our Mancunian heroine against a mysterious black van, which travels at night and abducts individuals at random, who knows for what heinous purpose, and again, as I’ve mentioned previously, it’s due for publication next spring.

It’s called SAVAGES – at least, that’s the title so far (it could still change) – it pits our Mancunian heroine against a mysterious black van, which travels at night and abducts individuals at random, who knows for what heinous purpose, and again, as I’ve mentioned previously, it’s due for publication next spring.Now, I’m guessing that one or two people are probably wondering if, because I’ve moved to a different publisher, SAVAGES might be the last we see of Lucy Clayburn? And are maybe asking themselves if KISS OF DEATH , published last August, was the last they’ll see of DS Mark Heckenburg?

No, basically.

I’ve agreed with Orion that I can continue to write for my pre-existing characters under their banner but must add the caveat that the first book they’re looking for will be an original, free-standing thriller, so though you’ll be seeing Heck and Lucy again, it won’t be straight away.

I realise this is not ideal for everyone.

KISS OF DEATH

ended on something of a cliff-hanger, and I’ve received quite a few letters and notes begging me to get on with the sequel. All I can say is that said sequel is already planned in detail, and will appear in due course – but patience will need to be a virtue.

I realise this is not ideal for everyone.

KISS OF DEATH

ended on something of a cliff-hanger, and I’ve received quite a few letters and notes begging me to get on with the sequel. All I can say is that said sequel is already planned in detail, and will appear in due course – but patience will need to be a virtue.Lure of the silver screen On top of that, there’s an even better reason why we need to keep the Lucy Clayburn ship afloat, which is that I’ve now signed a contract with The Shingle Media and Bierton Productions for a screen adaptation of the first three Lucy novels ( STRANGERS , SHADOWS and SAVAGES).

Whether for film or television remains to be seen, but how cool is this development?

Of course, it’s only an option at this stage, which means there are still lots of hoops for us all to jump through, but while there’s been interest before from the visual media in both Heck and Lucy, this is the first time that someone has actually come forward and slapped some money on the table.

I can’t say much more about it than that, except that it all feels very positive and exciting. Already, only a couple of days after the ink has dried on the forms, people have been bugging me about who’s going to play the leads.

Even though I’m always saying that this will never be down to me, and that even if it were, it’s far too early to be thinking about stuff like that, I always give my opinion anyway. I think it was Mark Billingham who, quoting personal experience, told me that if you name an actor you’d love to see play your lead-character often enough, word might reach said actor and that might actually make it happen.

So, I’ll say it again. There aren’t many actors I feel would make a better stab at Lucy Clayburn than Michelle Keegan. She started in the soap world, but she’s now become a very fine and respected performer in mainstream television. Plus … she’s from Manchester, as is Lucy, she’s aged in her early 30s, as is Lucy, she’s got a tough, streetwise aura, as has Lucy, and yes, hell, let’s admit it, she’s gorgeous … as is Lucy.

So, I’ll say it again. There aren’t many actors I feel would make a better stab at Lucy Clayburn than Michelle Keegan. She started in the soap world, but she’s now become a very fine and respected performer in mainstream television. Plus … she’s from Manchester, as is Lucy, she’s aged in her early 30s, as is Lucy, she’s got a tough, streetwise aura, as has Lucy, and yes, hell, let’s admit it, she’s gorgeous … as is Lucy. In response to who I’d have playing her villainous father, Frank McCracken, I couldn’t think of a better ‘likeable rogue’ character actor than Rufus Sewell. Again, he’s the right age, he’s got the right look, and he certainly has the acting chops.

In response to who I’d have playing her villainous father, Frank McCracken, I couldn’t think of a better ‘likeable rogue’ character actor than Rufus Sewell. Again, he’s the right age, he’s got the right look, and he certainly has the acting chops.But, and I can’t reiterate this strongly enough, I have no official role at all when it comes to casting (assuming we even reach that stage). And why would I have? It’s a 100% certainty that a professional casting director would be vastly better informed than me as to who is available, who is affordable and who has the necessary star-quality to take these roles forward and make any Lucy Clayburn adaptation into a seriously successful piece of film or TV.

But yes, I agree … it’s still fun to talk about it.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

ABSOLUTE PROOF

ABSOLUTE PROOF

by Peter James (2018)

Ross Hunter only learned about the accident that claimed his brother, Ricky’s life when he was working out in the gym several miles away and was suddenly beset with a bizarre vision, which he could never afterwards explain in any rational way.

This doesn’t exactly persuade him that there’s an afterlife, but it certainly leaves him thinking.

After this, the tragedies in Hunter’s life start to come thick and fast. A few years later, while working as a freelance reporter in Afghanistan, his party are ambushed by the Taliban, and though Hunter survives, he is the only one who does, which leaves him doubly mentally scarred by the experience. On top of that, when he returns home, he discovers his wife, Imogen, in bed with someone else.

Years pass, and though Hunter forgave Imogen’s infidelity, the trust they once shared is no longer quite there, even though she’s now pregnant again. His career, however, is going from strength to strength. Now widely respected as an investigative journalist, he chases only the biggest stories and gets fantastic spreads in the broadsheets. This is the reason why he is one day approached by ex-RAF officer and retired History of Art professor, Harry Cook, who offers him the scoop of a lifetime.

In short, Cook tells Hunter that he’s recently been given absolute proof of God’s existence, and that he needs a well-regarded journo to help him tell the story. He reinforces this remarkable claim by adding that he also has a message for Hunter from his deceased brother.

Hunter and Cook meet, and Hunter is startled at some of the personal information the old man imparts to him. This makes him take the stranger much more seriously, though even Hunter, with all that he’s been through, is stunned when Cook presents him with a manuscript, which he says was dictated to him by God during a séance, and which he says contains sets of three coordinates, each one relating to an item or place of incalculable religious significance, but all of which, when finally brought together, will be hugely beneficial to mankind.

The first of these – and this apparently will be the least difficult to locate – is the Holy Grail itself. When Hunter recovers from the shock of hearing this, he learns that the second is a personal but non-specified item connected to Jesus Christ, and that the third will have great relevance to the actual Second Coming. If it wasn’t for Cook’s revelations about Ricky, Hunter would likely as not disbelieve him, but his strange experiences have perhaps primed him to undertake this most momentous of investigations. Even then, Cook is unsure whether or not Hunter is the man for the job, and so at this early stage will only direct him to the possible resting place of the Grail. The rest will follow if this first part of the quest is successful. Before departing, however, he gives Hunter a stark warning that, as their ultimate goal is to bring belief back to mankind, and save all our souls, the power of Lucifer will be unleashed in many forms, no matter how foul, to try and intercept them.

Hunter still isn’t sure if he buys all this – and Imogen certainly doesn’t – but he commences his enquiry anyway, more in hope than optimism. He doesn’t stay tight-lipped about it either, and though, initially, there is bemusement and scepticism – radio presenter Sally Hughes is certainly interested, but Bishop Benedict Carmichael considers the whole thing too risky and attempts to dissuade Hunter from continuing – some powers follow his progress for entirely covetous reasons.

Dr Ainsley Bloor, the CEO of pharmaceutical giant, Kerr Kluge, a committed and aggressive atheist – a guy so committed to this cause, in fact, that he is literally using monkeys and typewriters to try and prove that pure chance was the origin of all things rather than Intelligent Design – is keen to get hold of whatever religious items Hunter can locate to try and make use of them in his development and sale of new medicines. Then there is Wesley Wenceslas, a British-based multi-millionaire evangelist and full-time conman, who would also love to have possession of such holy relics.

Neither of these very dangerous and determined men, among various others – fanatics drawn from all the world’s major religions! – will easily be dissuaded from attempting to possess whatever Hunter uncovers. As such, the first person to die, and only after considerable torture, is Harry Cook, with a high possibility that others will follow in short order.

The stage is truly set for a deadly, continent-hopping adventure, which, in due course, may even take Ross Hunter beyond the realms of this mortal world …

It’s a good thing it was Peter James who undertook to write this book, and not someone of lesser quality. Because when you think about it, a quest to prove the existence of God would likely be the greatest, most challenging mission in history, its outcome of interest to every single man and woman on Earth because there is probably no-one living today who hasn’t at one time or other pondered the existence of an overarching deity, or who hasn’t hoped and prayed that the human experience isn’t solely about our time on Earth.

The question is ... did Peter James succeed? In Absolute Proof , did he do justice to this phenomenal concept?

My personal view is that he did. Not just because this is the most massive novel he’s ever written, in both size and concept, (though it is, clocking in at nearly 600 pages!), or because he suddenly veers away from his more familiar territory of murder mysteries set on England’s South Coast (though he does, venturing clear across the globe), or even because it’s one of his best-written pieces to date (and when you consider that it’s Peter James we’re talking about here, that’s really saying something), but because I found the experience of reading it deeply emotionally affecting.

Ross Hunter is a bit of a neutral character by normal James standards. He’s obviously good at his job, but he’s not much of a fighter: he’s terrified during his sojourn to Afghanistan, he readily forgives his wife’s faithlessness and wordlessly tolerates a nagging fear that the child she is carrying is not his. He’s tough, though, and durable, and prepared to go to great lengths to reach his goal – and that’s the crux of it. Because Hunter, even though he’s no super cool hero, commences this journey on all our behalf, and what a journey it proves to be, taking him across the UK, to North Africa and eventually to America, throwing all kinds of obstacles into his route – both physical ones and spiritual ones – and yet increasingly he feels, as do we, that he’s on the trail of something truly amazing.

Though Absolute Proof is a big, big book, it’s a very smooth read, and I found myself accelerating through it, enjoying every page at the same time as yearning to reach a profound resolution.

Was my soul uplifted?

As I say, it’s an emotionally charged narrative – especially for those who actively seek answers of this sort – and yes, I want to know if God is out there as much as the next man, and as this book gets closer to answering that question than any other work of fiction I’ve ever encountered, I wasn’t exactly discouraged.

I should add that it’s not all completely plausible. The notion that one man could make so much ground so quickly when pursuing the most complex questions of all time stretches credulity a little, though to be fair, he does apparently get help from high places. But to make an issue of this would be to miss the point. The real story in Absolute Proof – as it can only ever be in a quest for God – centres around faith. Both believers and non-believers possess it (the former in His presence, the latter in His absence), and yet both sides struggle with these prescribed positions, because no-one can be certain that they are right, and probably never will be until the day of their death, which is why the search for absolute, undeniable proof is the ultimate human goal.