André Klein's Blog, page 5

October 12, 2020

Learning German with Stories: The Short & Funny Tales Of The Schildbürger

Let’s escape our current timeline for a bit, shall we? Let’s travel back in time to the Middle Ages, to the fabulous city of Schilda somewhere in the middle of Germany.

Its inhabitants were called “Schildbürger”, i.e. the citizens of Schilda. They were strange people. Everything they did, they did wrong. And everything they were told, they took literally. In fact, their stupidity was so widely known that people soon began to wonder how it was possible to be so dumb. Were they really that dense, or were they just pretending?

Apparently they hadn’t always been that dumb. In fact, the citizens of Schilda had once been so famously wise that they ventured far from their city to work as consultants and advisors for distant kings and emperors.

But as more and more of the wise people left Schilda, their city slowly degenerated. With noone to educate the young and maintain the city, the children stayed dumb and everything fell into disrepair. When the citizens of Schilda returned they were shocked to find their streets peppered with potholes, windowpanes broken, their youths badly-behaved and shingles swept from roofs by the wind.

“That’s what you get for being so wise!” their wives mocked them. And when the next congregation arrived in Schilda, asking for advice, the citizens of Schilda lied: “We’re all very sick” and the congregation left.

And thus an idea was born. A swineherd who had formerly been the town master mason in Pisa and built the famous Leaning Tower exclaimed: “I got it! Our wisdom is to blame for everything. Only stupidity will save us. If we’ll only manage to appear dumb, the kings and sultans will leave us in peace.”

“But how do you pretend to be dumb?” the citizens asked him. “Well,” he said. “Appearing dumb without actually being dumb isn’t that easy. But we’re smart people and we’ll do just fine.”

Over the course of the next two months they started practicing being dumb, first in secret. Then, as a first order of business, they built a grotesque new triangular town hall, because that would make them even more famous than Pisa! And they started building and rejoiced greatly in their newfound stupidity.

But the city’s teacher had concerns. “If you pretend to be smart, this doesn’t make you smart. But if you pretend to be dumb for a long time, perhaps this will actually make you dumb.” The citizens of Schilda were laughing at him.

“You see!” the teacher said. “It has already begun.”

~

The stories of the Schildbürger are from the so called chapbook tradition, similar to the Yiddish Chelm stories or the Wise Men of Gotham in the English speaking world and can make for enjoyable reading practice in German.

Today I’d like to share with you the original tale of how the Schildbürger built their triangular new town hall. I’ve prepared the text in such a way that you can hover over or — if you’re on a mobile device — touch underlined words to get immediate translations. Seperable verbs are marked in turqouise. So, without further ado …

Let’s go to Schilda!

Die Schildbürger bauen ein Rathaus

Der Plan, das neue Rathaus dreieckig zu bauen, stammte vom Schweinehirten. Er hatte den schiefen Turm von Pisa erbaut, darum erklärte er stolz: âEin dreieckiges Rathaus macht Schilda noch viel berühmter als Pisa!â Die anderen waren sehr zufrieden. Denn auch die Dummen werden gern berühmt. Das war im Mittelalter nicht anders als heute.

So gingen die Schildbürger schon am nächsten Tag an die Arbeit. Sechs Wochen später hatten sie die drei Mauern aufgebaut, es fehlte nur noch das Dach. Als das Dach fertig war, fand die feierliche Einweihung des neuen Rathauses statt. Alle Einwohner gingen in das dreieckige Gebäude hinein.

Aber da stürzten sie auch schon durcheinander. Die drin waren, wollten wieder heraus. Die drauÃen standen, wollten hinein. Es gab ein

fürchterliches Gedränge! Endlich landeten sie alle wieder im Freien. Sie blickten einander ratlos an und fragten aufgeregt: âWas war denn eigentlich los?â Der Schuhmacher überlegte und sagte: âIn unserem Rathaus ist es dunkel!â

Da stimmten alle zu. Aber woran lag es? Lange wussten sie keine Antwort. Am Abend trafen sie sich im Wirtshaus. Sie besprachen, wie man Licht ins Rathaus hineinschaffen konnte. Erst nach dem fünften Glas Bier sagte der Hufschmied nachdenklich: âWir sollten das Licht wie Wasser hineintragen!â âHurra!â, riefen alle begeistert.

Am nächsten Tag schaufelten die Schildbürger den Sonnenschein in Eimer und Kessel, Kannen und Töpfe. Andere hielten Kartoffelsäcke ins

Sonnenlicht, banden dann die Säcke schnell zu und schleppten sie ins Rathaus. Dort banden sie die Säcke auf, schütteten das Licht ins Dunkel und rannten wieder auf den Markt hinaus, wo sie die leeren Säcke wieder vollschaufelten. So machten sie es bis zum Sonnenuntergang. Aber im Rathaus war es noch dunkel wie am Tag zuvor. Da liefen alle traurig wieder ins Freie.

Wie sie so herumstanden, kam ein Landstreicher vorbei. Er fragte: âWas ist denn los? Was fehlt euch?â Sie erzählten ihm von ihrem Problem. Er dachte nach und sagte: âKein Wunder, dass es in eurem Rathaus dunkel ist! Ihr müsst das Dach abdecken!â Sie waren sehr erstaunt und schlugen ihm vor, in Schilda zu bleiben, solange er es wollte. Tags darauf deckten die Schildbürger das Dach ab, und es wurde im Rathaus sonnenhell! Es störte sie nicht, dass sie kein Dach über dem Kopf hatten! Das ging lange Zeit gut, bis es im Herbst regnete. Die Schildbürger, die gerade in ihrem Rathaus saÃen, wurden bis auf die Haut nass. So rannten sie schnell nach Hause.

Als sie am Morgen den Landstreicher um Rat fragen wollten, war er verschwunden. So versuchten sie es mit dem Rathaus ohne Dach. Als es dann aber zu schneien begann, deckten sie den Dachstuhl, wie vorher, mit Ziegeln. Nun warâs im Rathaus aber wieder ganz dunkel. Doch diesmal steckte sich jeder einen brennenden Holzspan an den Hut. Leider erloschen die Späne schnell, und wieder saÃen die Männer im Dunkeln. Plötzlich rief der Schuster: âDa! Ein Lichtstrahl!â Tatsächlich! Durch ein Loch kam etwas Sonnenlicht herein. Alle blickten auf den Lichtstrahl. âOh wir Esel! Wir haben ja die Fenster vergessen!â, riefen die Schildbürger.

Noch am Abend waren die Fenster fertig. So wurden die Schildbürger durch die vergessenen Fenster berühmt. Es dauerte nicht lange, da kamen auch Reisende nach Schilda und lieÃen ihr Geld in der Stadt. âSeht ihrâ, sagte der Ochsenwirt, âals wir gescheit waren, mussten wir das Geld in der Fremde verdienen. Jetzt, da wir dumm geworden sind, bringt man es uns ins Haus!â

~

Rathaus: city hall | dreieckig: triangular | zu bauen: to build, | stammte vom: came from | Schweinehirten: pig herder | schiefen: crooked | Turm: tower | erbaut: built | darum: therefore | erklärte: explained | stolz: proudly | noch viel: yet much | berühmter: more famous | zufrieden: satisfied | denn: because | die Dummen: the stupid ones | werden gern: like to become | Mittelalter: middle ages | nicht anders als heute: no different than today | schon: already| später: later | Mauern: walls | aufgebaut: erected | es fehlte: it was missing | Dach: roof | Als: when | fertig war: was ready | fand statt: took place | feierliche: festive | Einweihung: inauguration | Einwohner: residents | gingen hinein: went inside | Gebäude: building | stürzten: stumbled | durcheinander: all over the place | Die drin waren: those that were inside | wollten: wanted | heraus: out | drauÃen: outside | hinein: inside | fürchterliches: terrible | Gedränge: jostling | Endlich: finally | landeten: landed | im Freien: in the open air | blickten: looked at | einander: each other | ratlos: helplessly | fragten: asked | aufgeregt: excitedly | Was war denn eigentlich los?: what was actually going on? | Schuhmacher: shoemaker | überlegte: deliberated | dunkel: dark | stimmten zu: agreed | woran lag es: what was the reason | lange: for a long time | wussten: knew | Antwort: answer | trafen: met | Wirtshaus: tavern | besprachen: discussed | Licht: light | ins: into the | hineinschaffen: get inside | erst: only | fünften: fifth | Bier: beer | Hufschmied: blacksmith | nachdenklich:  pondering | sollten: should | Wasser: water | hineintragen: carry inside | riefen: exclaimed | begeistert: excitedly | schaufelten: shovelled | Sonnenschein: sunshine | Eimer: buckets | Kessel: cauldrons | Kannen: tankards | Töpfe: pots | hielten: held | Kartoffelsäcke: potato sacks | Sonnenlicht: sunlight | banden zu: tied up | schnell: fast | schleppten: dragged | banden auf: untied | schütteten: poured | leeren: empty | vollschaufelten: shovelled full | bis zum: until the | Sonnenuntergang: sunset | noch: still | wie am Tag zuvor: like the day before | traurig: unhappily | herumstanden: stood around | kam vorbei: came by | Landstreicher: hobo | Was ist denn los?: what’s the matter? | Was fehlt euch: What ails you? | dachte nach: pondered | Kein Wunder: no wonder | abdecken: uncover | erstaunt: astonished | schlugen ihm vor: suggested to him | bleiben: stay | solange: as long as | wollte: wanted | Tags darauf: the next day | deckten ab: uncovered | sonnenhell: sunny | es störte sie nicht: it did not bother them | Herbst: autumn | regnete: rained | Haut: skin | nass: wet | rannten: ran | um Rat fragen: ask for advice | verschwunden: disappeared | versuchten: tried | schneien: snow | deckten: covered | Dachstuhl: roof truss | wie vorher: as before | Ziegeln: bricks | steckte: stuck| jeder: each one| brennenden: burning | Holzspan: wood chip | Hut: hat | Leider: unfortunately | erloschen: expired | Späne: chips | Schuster: cobbler | Lichtstrahl: light beam | Tatsächlich: indeed| Loch: hole | Esel: donkeys | Fenster: window | vergessen: forgotten | wurden: became | dauerte: lasted | Reisende: travelers | lieÃen: let | Geld: money | gescheit: clever | verdienen: earn | dumm: stupid | geworden: becomeCreditsCopyright of original text: unknown (shared here for educational purposed only)

Narration: Leseonkel

Translation & code: André Klein

The post Learning German with Stories: The Short & Funny Tales Of The Schildbürger appeared first on LearnOutLive.

Learning German with Stories: The Short & Funny Tales Of The Schildbürger

Let’s escape 2020 for a bit, shall we? Let’s travel back in time to the Middle Ages, to the fabulous city of Schilda somewhere in the middle of Germany.

Its inhabitants were called “Schildbürger”, i.e. the citizens of Schilda. They were strange people. Everything they did, they did wrong. And everything they were told, they took literally. In fact, their stupidity was so widely known that people soon began to wonder how it was possible to be so dumb. Were they really that dense, or were they just pretending?

Apparently they hadn’t always been that dumb. In fact, the citizens of Schilda had once been so famously wise that they ventured far from their city to work as consultants and advisors for distant kings and emperors.

But as more and more of the wise people left Schilda, their city slowly degenerated. With noone to educate the young and maintain the city, the children stayed dumb and everything fell into disrepair. When the citizens of Schilda returned they were shocked to find their streets peppered with potholes, windowpanes broken, their youths badly-behaved and shingles swept from roofs by the wind.

“That’s what you get for being so wise!” their wives mocked them. And when the next congregation arrived in Schilda, asking for advice, the citizens of Schilda lied: “We’re all very sick” and the congregation left.

And thus an idea was born. A swineherd who had formerly been the town master mason in Pisa and built the famous Leaning Tower exclaimed: “I got it! Our wisdom is to blame for everything. Only stupidity will save us. If we’ll only manage to appear dumb, the kings and sultans will leave us in peace.”

“But how do you pretend to be dumb?” the citizens asked him. “Well,” he said. “Appearing dumb without actually being dumb isn’t that easy. But we’re smart people and we’ll do just fine.”

Over the course of the next two months they started practicing being dumb, first in secret. Then, as a first order of business, they built a grotesque new triangular town hall, because that would make them even more famous than Pisa! And they started building and rejoiced greatly in their newfound stupidity.

But the city’s teacher had concerns. “If you pretend to be smart, this doesn’t make you smart. But if you pretend to be dumb for a long time, perhaps this will actually make you dumb.” The citizens of Schilda were laughing at him.

“You see!” the teacher said. “It has already begun.”

~

The stories of the Schildbürger are from the so called chapbook tradition, similar to the Yiddish Chelm stories or the Wise Men of Gotham in the English speaking world and can make for enjoyable reading practice in German.

Today I’d like to share with you the original tale of how the Schildbürger built their triangular new town hall. I’ve prepared the text in such a way that you can hover over or — if you’re on a mobile device — touch underlined words to get immediate translations. Seperable verbs are marked in turqouise. So, without further ado …

Let’s go to Schilda!

Die Schildbürger bauen ein Rathaus

Der Plan, das neue Rathaus dreieckig zu bauen, stammte vom Schweinehirten. Er hatte den schiefen Turm von Pisa erbaut, darum erklärte er stolz: „Ein dreieckiges Rathaus macht Schilda noch viel berühmter als Pisa!“ Die anderen waren sehr zufrieden. Denn auch die Dummen werden gern berühmt. Das war im Mittelalter nicht anders als heute.

So gingen die Schildbürger schon am nächsten Tag an die Arbeit. Sechs Wochen später hatten sie die drei Mauern aufgebaut, es fehlte nur noch das Dach. Als das Dach fertig war, fand die feierliche Einweihung des neuen Rathauses statt. Alle Einwohner gingen in das dreieckige Gebäude hinein.

Aber da stürzten sie auch schon durcheinander. Die drin waren, wollten wieder heraus. Die draußen standen, wollten hinein. Es gab ein

fürchterliches Gedränge! Endlich landeten sie alle wieder im Freien. Sie blickten einander ratlos an und fragten aufgeregt: „Was war denn eigentlich los?“ Der Schuhmacher überlegte und sagte: „In unserem Rathaus ist es dunkel!“

Da stimmten alle zu. Aber woran lag es? Lange wussten sie keine Antwort. Am Abend trafen sie sich im Wirtshaus. Sie besprachen, wie man Licht ins Rathaus hineinschaffen konnte. Erst nach dem fünften Glas Bier sagte der Hufschmied nachdenklich: „Wir sollten das Licht wie Wasser hineintragen!“ „Hurra!“, riefen alle begeistert.

Am nächsten Tag schaufelten die Schildbürger den Sonnenschein in Eimer und Kessel, Kannen und Töpfe. Andere hielten Kartoffelsäcke ins

Sonnenlicht, banden dann die Säcke schnell zu und schleppten sie ins Rathaus. Dort banden sie die Säcke auf, schütteten das Licht ins Dunkel und rannten wieder auf den Markt hinaus, wo sie die leeren Säcke wieder vollschaufelten. So machten sie es bis zum Sonnenuntergang. Aber im Rathaus war es noch dunkel wie am Tag zuvor. Da liefen alle traurig wieder ins Freie.

Wie sie so herumstanden, kam ein Landstreicher vorbei. Er fragte: „Was ist denn los? Was fehlt euch?“ Sie erzählten ihm von ihrem Problem. Er dachte nach und sagte: „Kein Wunder, dass es in eurem Rathaus dunkel ist! Ihr müsst das Dach abdecken!“ Sie waren sehr erstaunt und schlugen ihm vor, in Schilda zu bleiben, solange er es wollte. Tags darauf deckten die Schildbürger das Dach ab, und es wurde im Rathaus sonnenhell! Es störte sie nicht, dass sie kein Dach über dem Kopf hatten! Das ging lange Zeit gut, bis es im Herbst regnete. Die Schildbürger, die gerade in ihrem Rathaus saßen, wurden bis auf die Haut nass. So rannten sie schnell nach Hause.

Als sie am Morgen den Landstreicher um Rat fragen wollten, war er verschwunden. So versuchten sie es mit dem Rathaus ohne Dach. Als es dann aber zu schneien begann, deckten sie den Dachstuhl, wie vorher, mit Ziegeln. Nun war’s im Rathaus aber wieder ganz dunkel. Doch diesmal steckte sich jeder einen brennenden Holzspan an den Hut. Leider erloschen die Späne schnell, und wieder saßen die Männer im Dunkeln. Plötzlich rief der Schuster: „Da! Ein Lichtstrahl!“ Tatsächlich! Durch ein Loch kam etwas Sonnenlicht herein. Alle blickten auf den Lichtstrahl. „Oh wir Esel! Wir haben ja die Fenster vergessen!“, riefen die Schildbürger.

Noch am Abend waren die Fenster fertig. So wurden die Schildbürger durch die vergessenen Fenster berühmt. Es dauerte nicht lange, da kamen auch Reisende nach Schilda und ließen ihr Geld in der Stadt. „Seht ihr“, sagte der Ochsenwirt, „als wir gescheit waren, mussten wir das Geld in der Fremde verdienen. Jetzt, da wir dumm geworden sind, bringt man es uns ins Haus!“

~

Rathaus: city hall | dreieckig: triangular | zu bauen: to build, | stammte vom: came from | Schweinehirten: pig herder | schiefen: crooked | Turm: tower | erbaut: built | darum: therefore | erklärte: explained | stolz: proudly | noch viel: yet much | berühmter: more famous | zufrieden: satisfied | denn: because | die Dummen: the stupid ones | werden gern: like to become | Mittelalter: middle ages | nicht anders als heute: no different than today | schon: already| später: later | Mauern: walls | aufgebaut: erected | es fehlte: it was missing | Dach: roof | Als: when | fertig war: was ready | fand statt: took place | feierliche: festive | Einweihung: inauguration | Einwohner: residents | gingen hinein: went inside | Gebäude: building | stürzten: stumbled | durcheinander: all over the place | Die drin waren: those that were inside | wollten: wanted | heraus: out | draußen: outside | hinein: inside | fürchterliches: terrible | Gedränge: jostling | Endlich: finally | landeten: landed | im Freien: in the open air | blickten: looked at | einander: each other | ratlos: helplessly | fragten: asked | aufgeregt: excitedly | Was war denn eigentlich los?: what was actually going on? | Schuhmacher: shoemaker | überlegte: deliberated | dunkel: dark | stimmten zu: agreed | woran lag es: what was the reason | lange: for a long time | wussten: knew | Antwort: answer | trafen: met | Wirtshaus: tavern | besprachen: discussed | Licht: light | ins: into the | hineinschaffen: get inside | erst: only | fünften: fifth | Bier: beer | Hufschmied: blacksmith | nachdenklich: pondering | sollten: should | Wasser: water | hineintragen: carry inside | riefen: exclaimed | begeistert: excitedly | schaufelten: shovelled | Sonnenschein: sunshine | Eimer: buckets | Kessel: cauldrons | Kannen: tankards | Töpfe: pots | hielten: held | Kartoffelsäcke: potato sacks | Sonnenlicht: sunlight | banden zu: tied up | schnell: fast | schleppten: dragged | banden auf: untied | schütteten: poured | leeren: empty | vollschaufelten: shovelled full | bis zum: until the | Sonnenuntergang: sunset | noch: still | wie am Tag zuvor: like the day before | traurig: unhappily | herumstanden: stood around | kam vorbei: came by | Landstreicher: hobo | Was ist denn los?: what’s the matter? | Was fehlt euch: What ails you? | dachte nach: pondered | Kein Wunder: no wonder | abdecken: uncover | erstaunt: astonished | schlugen ihm vor: suggested to him | bleiben: stay | solange: as long as | wollte: wanted | Tags darauf: the next day | deckten ab: uncovered | sonnenhell: sunny | es störte sie nicht: it did not bother them | Herbst: autumn | regnete: rained | Haut: skin | nass: wet | rannten: ran | um Rat fragen: ask for advice | verschwunden: disappeared | versuchten: tried | schneien: snow | deckten: covered | Dachstuhl: roof truss | wie vorher: as before | Ziegeln: bricks | steckte: stuck| jeder: each one| brennenden: burning | Holzspan: wood chip | Hut: hat | Leider: unfortunately | erloschen: expired | Späne: chips | Schuster: cobbler | Lichtstrahl: light beam | Tatsächlich: indeed| Loch: hole | Esel: donkeys | Fenster: window | vergessen: forgotten | wurden: became | dauerte: lasted | Reisende: travelers | ließen: let | Geld: money | gescheit: clever | verdienen: earn | dumm: stupid | geworden: become

Credits

Copyright of original text: unknown (shared here for educational purposed only)

Narration: Leseonkel

Translation & code: André Klein

The post Learning German with Stories: The Short & Funny Tales Of The Schildbürger appeared first on LearnOutLive.

September 14, 2020

The German Prefix âbe-â Explained

Once you’ve started learning a few German verbs, you’ll notice that there are a number of awkwardly similar verbs which have a slightly similar yet sufficiently different meaning. I’m talking about those pesky German verb prefixes which sometimes are just two or three letters long but completely change the meaning of the verb.

Let’s take the verb gehen (go/walk) for example and look at how adding prefixes can change the meaning:

weggehen – to go away

vorgehen – to go ahead

nachgehen – to pursue

entgehen – to avoid/escape

aufgehen – to rise/”go up”

durchgehen – to go through

(These are just some of the options. Take a look at this monster of a list for a more comprehensive overview of possible combinations.)

Some of these are more straightforward than others. Especially those which describe a position in three-dimensional space like -auf, -ab, -unter, -hinter, -über, etc. are pretty logical:

weg = away â weggehen = to go away

auf = up â aufgehen = to “go up” (rise)

durch = through â durchgehen = to pass through

So if you know the meaning of prefixes you can easily understand new verbs that you haven’t seen before, simply by splitting them into their parts, at least in theory.

The problem is that we have many prefixes which don’t seem to have a clear-cut meaning, such as dar-, ge-, zer-, etc. How can you make sense of these? Well, it’s complicated, and instead of making sweeping generalizations which then require a million exceptions, it’s helpful to look at these prefixes in more detail.

Today I’d like to talk a bit about the prefix be-, since I received the following question on the newsletter:

To “be-” or not to “be-” …There are a quite a few cases where there are verbs and related be-verbs, such as danken and bedanken or folgen and befolgen. If one looks these words up in a dictionary often the meaning is identical or very close. In particular when would one use folgen (and not befolgen ), and when would one use befolgen (and not folgen )? – Myron

First of all, let’s look at some verbs and how they change when adding “be-“:

sprühen – to spray

besprühen- to spray on

kleben – to glue

bekleben – to stick (something) on (something)

gehen – to walk

begehen – to walk on

At first glance, it seems simple, right? The prefix “be-” simply seems to mean “on”. And yes, sometimes it does appear like that, but this will only get you so far. Let’s look at some more examples:

schreiben – to write

beschreiben – describe

leben – to live

beleben – to enliven

rühren – to stir

berühren – to touch

As you can see the idea that “be-” means “on” already falls flat here. In fact, can you spot any shared meaning here at all? No? Well, you’re not alone. That’s because the prefix “be-” has no explicit meaning.

But then what’s happening here? Why do these verbs use this prefix all? Is it completely random? Natürlich nicht.

According to Duden, the German grammar and spelling bible, the prefix “be-” has two very specific functions:

1. a) transforms intransitive verbs into transitive ones

b) takes the prepositional object in intransitive formations and transforms it into an accusative object.

2. expresses within formations with nouns (or 2nd participles) that a person or thing is being endowed, equipped or provided with something

Too much jargon? Don’t worry, we’ll unpack these step by step.

1. a) Transitize this!Before we continue, here’s a quick reminder about the difference between transitive and intransitive verbs:

Transitive verbs are verbs which must or can have an object:

Sarah braucht Geld. – Sarah needs money.

Peter isst (einen D̦ner). РPeter is eating (a doner kebab).

Intransitive verbs never have an object:

Sarah schläft. – Sarah is sleeping.

So, according to our grammar bible adding the prefix “be-” should transform intransitive verbs to transitive ones. Let’s try it out:

Peter labert. – Peter’s babbling.

Peter belabert Sarah – Peter’s babbling at Sarah.

b) From Prepositional Object to Accusative ObjectThe second use case of “be-” is where we have a transitive verb with a prepositional object that gets transformed into an accusative object.

Quick reminder: a prepositional object is an object that is connected to the verb via a preposition:

Ich warte auf den Zug. – I’m waiting for the train.

Sie springen ins Wasser. – They are jumping into the pool.

So, “be-” is supposed to transform these prepositional objects into “regular” old accusative objects. Time for an example:

Sie bauen auf der Wiese. – They’re building on the meadow.

Sie bebauen die Wiese. – They’re building on the meadow.

As you can see the meaning of the sentence doesn’t change here, but the structure does. We can say the same thing either with a prepositional object or — by adding “be-” — with an accusative object.

It’s precisely this function of the prefix “be-” which gave us the (false) notion above that it means “on”. Let’s look at sprühen/besprühen again:

Ich sprühe auf die Wand. – I’m spraying onto the wall. (prepositional object)

Ich besprühe die Wand. – I’m spraying onto the wall. (accusative object)

Something similar happens with one of the verbs Myron asked about, with a small twist:

Ich danke für die Blumen. – I’m thanking for the flowers.

Ich bedanke mich für die Blumen – I’m thanking for the flowers.

While at first glance it looks like the prepositional object (“für die Blumen”) hasn’t changed, we still see the introduction of an accusative object. How? By adding “be-” to danken, the verb becomes reflexive! And the reflexive pronoun (“mich”) now occupies the position of the accusative object. Confusing? Just keep in mind that (sich) bedanken is reflexive, while danken is not, and you should be fine.

2. Let’s Get EquippedThe second function mentioned by Duden is when “be-” takes a noun, and turns it into a verb which expresses that someone or something is being endowed, equipped or provided with said thing:

die Blume – flower

Ich beblume den Balkon. – I equip the balcony with flowers.

Der Balkon ist jetzt beblumt. – The balcony is now equipped with flowers.

der Schlips – tie

Sarah beschlipst Peter. – Sarah equips Peter with a tie.

Peter ist jetzt beschlipst. – Peter is now equipped with a tie.

Summary & ExceptionI hope this hasn’t been too confusing so far. Let’s do a quick recap:

“be-” has no explicit meaning, but:it transforms intransitive verbs into transitive onesit changes prepositional objects into accusative objectsit creates verbs out of nouns which express that something is being equipped with said nounSo far so good. But we still haven’t talked about the other verb pair that Myron asked about: folgen/befolgen. Unfortunately it doesn’t seem to follow any of the functions discussed above:

folgen is not an intransitive verb (1a)

folgen does not come with a prepositional object (1b)

befolgen does not express that something or someone is being equipped with something (2)

So what’s going on here? Let’s take a closer look at how this verb + prefix works:

Wir folgen der Anweisung. – We’re following the directive.

Wir befolgen die Anweisung. – We’re following the directive.

As you can see above, both sentences have the exact same translation, but the difference is in the object case. Folgen requires a dative object, whereas befolgen uses an accusative object. Does that mean that folgen and befolgen always mean exactly the same thing? Well, they can, but they don’t have to.

folgen means to follow (both literally, i.e. physically following and figuratively, i.e. to act according to a plan, protocol, etc.)

befolgen means to follow, but only figuratively

So I can say:

Ich folge dem Hund. – I’m following the dog.

But saying: “Ich befolge den Hund” while grammatically correct, is complete nonsense, because a dog is not a plan, set of orders, directive, etc. But you could totally say:

Ich befolge den Ernährungsplan für meinen Hund. – I’m following the nutrition protocol for my dog.

So, when should you use folgen or befolgen?

If you don’t want to make a distinction between physically following an object, animal or person, or more abstractly following a plan, protocol, etc. use folgen. It always works.

If you want to talk explicitly about following a plan, set of directives, rules, protocol, etc. (in contrast to physically following an object, animal or person) use befolgen.

–

The post The German Prefix “be-” Explained appeared first on LearnOutLive.

The German Prefix “be-” Explained

Once you’ve started learning a few German verbs, you’ll notice that there are a number of awkwardly similar verbs which have a slightly similar yet sufficiently different meaning. I’m talking about those pesky German verb prefixes which sometimes are just two or three letters long but completely change the meaning of the verb.

Let’s take the verb gehen (go/walk) for example and look at how adding prefixes can change the meaning:

weggehen – to go away

vorgehen – to go ahead

nachgehen – to pursue

entgehen – to avoid/escape

aufgehen – to rise/”go up”

durchgehen – to gothrough

(These are just some of the examples. Take a look at this monster of a list for a more comprehensive overview of possible combinations.)

Some of these are more straightforward than others. Especially those which describe a position in three-dimensional space like -auf, -ab, -unter, -hinter, -über, etc. are pretty logical:

weg = away → weggehen = to go away

auf = up → aufgehen = to “go up” (rise)

durch = through → durchgehen = to pass through

So if you know the meaning of prefixes you can easily understand new verbs that you haven’t seen before, simply by splitting them into their parts, at least in theory.

The problem is that we have many prefixes which don’t seem to have a clear-cut meaning, such as dar-, ge-, zer-, etc.? How can you make sense of these? Well, it’s complicated, and instead of making sweeping generalizations which then require a million exceptions, it’s helpful to look at these prefixes in more detail.

Today I’d like to talk a bit about the prefix be-, since I received the following question on the newsletter:

There are a quite a few cases where there are verbs and related be-verbs, such as danken and bedanken or folgen and befolgen. If one looks these words up in a dictionary often the meaning is identical or very close. In particular when would one use folgen (and not befolgen ), and when would use befolgen (and not folgen )? – Myron

To “be-” or not to “be-” …

First of all, let’s look at some verbs and how they change when adding “be-“:

sprühen – to spray

besprühen- to spray on

kleben – to glue

bekleben – to stick (something) on (something)

gehen – to walk

begehen – to walk on

At first glance, it seems simple, right? The prefix “be-” simply seems to mean “on”. And yes, sometimes it does seem to mean that, but this will only get you so far. Let’s look at some more examples:

schreiben – to write

beschreiben – describe

leben – to live

beleben – to enliven

rühren – to stir

berühren – to touch

As you can see the idea that “be-” means “on” already falls flat here. In fact, can you spot any shared meaning here at all? No? Well, you’re not alone. That’s because the prefix “be-” has no explicit meaning.

But then what’s happening here? Why do these verbs use this prefix all? Is it completely random? Natürlich nicht.

According to Duden, the German grammar and spelling bible, the prefix “be-” has two very specific functions:

1. a) transforms intransitive verbs into transitive ones

b) takes the prepositional object in intransitive formations and transforms it into an accusative object.

2. expresses within formations with nouns (or 2nd participles) that a person or thing is being endowed, equipped or provided with something

Too much jargon? Don’t worry, we’ll unpack these step by step.

1. a) Transitize this!

Before we continue, here’s a quick reminder about the difference between transitive and intransitive verbs:

Transitive verbs are verbs which must or can have an object:

Sarah braucht Geld. – Sarah needs money.

Peter isst (einen Döner). – Peter is eating (a doner kebab).

Intransitive verbs never have an object:

Sarah schläft. – Sarah is sleeping.

So, according to our grammar bible adding the prefix “be-” should transform intransitive verbs to transitive ones. Let’s try it out:

Peter labert. – Peter’s babbling.

Peter belabert Sarah – Peter’s babbling at Sarah.

b) From Prepositional Object to Accusative Object

The second use case of “be-” is where we have a transitive verb with a prepositional object that gets transformed into an accusative object.

Quick reminder: a prepositional object is an object that is connected to the verb via a preposition:

Ich warte auf den Zug. – I’m waiting for the train.

Sie springen ins Wasser. – They are jumping into the pool.

So, “be-” is supposed to transform these prepositional objects into “regular” old accusative objects. Time for an example:

Sie bauen auf der Wiese. – They’re building on the meadow.

Sie bebauen die Wiese. – They’re building on the meadow.

As you can see the meaning of the sentence doesn’t change here, but the structure does. We can say the same thing either with a prepositional object or — by adding “be-” — with an accusative object.

It’s precisely this function of the prefix “be-” which gave us the (false) notion above that it means “on”. Let’s look at sprühen/besprühen again:

Ich sprühe auf die Wand. – I’m spraying onto the wall. (prepositional object)

Ich besprühe die Wand. – I’m spraying onto the wall. (accusative object)

Something similar happens with one of the verbs Myron asked about, with a small twist:

Ich danke für die Blumen. – I’m thanking for the flowers.

Ich bedanke mich für die Blumen – I’m thanking for the flowers.

While at first glance it looks like the prepositional object (“für die Blumen”) hasn’t changed, we still see the introduction of an accusative object. How? By adding “be-” to danken, the verb becomes reflexive! And the reflexive pronoun (“mich”) now occupies the position of the accusative object. Confusing? Just keep in mind that (sich) bedanken is reflexive, while danken is not, and you should be fine.

2. Upgrading Things

The second function mentioned by Duden is when “be-” takes a noun, and turns it into a verb which expresses that someone or something is being endowed, equipped or provided with said thing:

die Blume – flower

Ich beblume den Balkon. – I equip the balcony with flowers.

Der Balkon ist jetzt beblumt. – The balcony is now equipped with flowers.

der Schlips – tie

Sarah beschlipst Peter. – Sarah equips Peter with a tie.

Peter ist jetzt beschlipst. – Peter is now equipped with a tie.

Summary & Exception

I hope this hasn’t been too confusing so far. Let’s do a quick recap:

“be-” has no explicit meaning, but:

it transforms intransitive verbs into transitive ones

it changes prepositional objects into accusative objects

it creates verbs out of nouns which express that something is being equipped with said noun

So far so good. But we still haven’t talked about the other verb pair that Myron asked about: folgen/befolgen. Unfortunately it doesn’t seem to follow any of the functions discussed above:

folgen is not an intransitive verb (1a)

folgen does not come with a prepositional object (1b)

befolgen does not express that something or someone is being equipped with something (2)

So what’s going on here? Let’s take a closer look at how this verb + prefix works:

Wir folgen der Anweisung. – We’re following the directive.

Wir befolgen die Anweisung. – We’re following the directive.

As you can see above, both sentences have the exact same translation, but the difference is in the object case. Folgen requires a dative object, whereas befolgen uses an accusative object. Does that mean that folgen and befolgen always mean exactly the same thing? Well, they can, but they don’t have to.

folgen means to follow (both literally, i.e. physically following and figuratively, i.e. to act according to a plan, protocol, etc.)

befolgen means to follow, but only figuratively

So I can say:

Ich folge dem Hund. – I’m following the dog.

But saying: “Ich befolge den Hund” while grammatically correct, is complete nonsense, because a dog is not a plan, set of orders, directive, etc. But you could totally say:

Ich befolge den Ernährungsplan für meinen Hund. – I’m following the nutrition protocol for my dog.

So, when should you use folgen or befolgen?

If you don’t want to make a distinction between physically following an object, animal or person, or more abstractly following a plan, protocol, etc. use folgen. It always works.

If you want to talk explicitly about following a plan, set of directives, rules, protocol, etc. (in contrast to physically following an object, animal or person) use befolgen.

–

The post The German Prefix “be-” Explained appeared first on LearnOutLive.

August 26, 2020

âI Canât Get No â¦â: N-Declension In German

Welcome back to another instalment of our German grammar series in which I answer some of the questions that have popped up on the newsletter. Today’s question is by Douglas:

Rule Of The WeakMy question: why do some German nouns add a final ‘n’ in the acc. sing., e.g. ‘meinen Namenâ , einen Geldautomaten, which, of course has to add -en, since the nom. ends in âtâ. Is there a rule that governs this, and if not, is there a list of offenders one can just learn!

First of all, these nouns belong to the group of the so called “N-Declension” and are also called “weak nouns”. But before you start wondering whether these nouns are in need of some serious gym time or protein shakes, let’s look at their basic characteristics:

Weak nouns …

are always masculineget an additional -n in their Akkusativ, Genitiv and Dativ declension (in singular!)In other words: not all masculine nouns are weak nouns, but all weak nouns are masculine*. In the case of Douglas’ question, Geldautomat is of course masculine (der Automat).

Let’s have a look at some examples:

Ich habe diesen Namen noch nie gehört. [Akkusativ – der Name]Das ist der Film des neuen Produzenten. [Genitiv – der Produzent]Sie hat dem Jungen Komplimente gemacht. [Dativ – der Junge]As you can see all these nouns are masculine and they receive an additional -n in their Akkusativ, Genitiv and Dativ (singular) declensions.

In plural their declension endings are identical. In fact, you only know that they are plural because of the article. Let’s run through the same three examples again, but see how we switch to plural (article colored turquoise) and the declension stays the same:

Ich habe diese Namen och nie gehört.Das ist der Film der neuen Produzenten.Sie hat den Jungen Komplimente gemacht.List Of N-OffendersThe amount of nouns belonging to this group of “n-declensions” is relatively small, but there are some patterns for spotting them, aside from being masculine.

Many of these nouns end on -e, -ent, -ant, -ist, -oge or -at.Mostly they describe nationalities, persons or animalsLet’s have a look at some of these:

Nationalities:

der Deutsche, der Russe, der Franzose, der Pole, der Türke, der Rumäne, der Afghane, der Bulgare, der Ire, der Schotte, der Chinese, der Schwede, der Finne, der Däne, etc.Examples:

“Ich kenne diesen Franzosen aus dem Fernsehen.” (Akkusativ)

“Das ist die Tochter des Polen von nebenan.” (Genitiv)

“Ich werde mit dem Afghanen sprechen.” (Dativ)

Persons:

der Spezialist, der Journalist, der Polizist, der Christ [-ist]der Produzent, der Präsident, der Agent [-ent]der Intendant, der Leutnant, der Informant [-ant]der Virologe, der Urologe, der Pädagoge [-oge]der Bürokrat, der Aufsichtsrat, der Apparat, der Soldat [-at]“Ich mag diesen Bürokraten nicht.” (Akkusativ)

“Die Arbeit des Polizisten ist nicht leicht.” (Genitiv)

“Sie gibt dem Agenten die Papiere.” (Dativ)

Animals

der Elefant, der Affe, der Löwe, der Hase, der Ochse, der Bulle, der Rabe, etc.“Ich finde diesen Affen lustig.” (Akkusativ)

“Das Leben eines Löwen im Zoo ist traurig.” (Genitiv)

“Sie geben dem Hasen Futter.” (Dativ)

*Exceptions

As always with grammar, there are exceptions. Here are some words that are part of the group of “weak nouns” but don’t necessarily fit into our previous categories:

der Architekt, der Chaot, der Held, der Fotograf, der Herr, der Bauer, der Pilot, der Prinz [masculine persons, but not ending on -e, -ent, -ant, -ist, -oge or -at.]das Herz [the only non-masculine weak noun]der Automat, der Diamant [masculine nouns ending on -e, -ent, -ant, -ist, -oge or -at, but not nationalities, persons or animals]der Bär, der Fink, der Spatz [masculine animals, but not ending on -e, -ent, -ant, -ist, -oge or -at]A Dying BreedSo many rules, so many exceptions. Yes, but before you despair, I have some good news: the “n-declension” is almost extinct in colloquial German, i.e. you will hear people leave out the “-n” all the time in daily life, especially in Akkusativ and Dativ. It’s very common to hear people say things like:

“Frag den Pilot!”“Kennst du den Prinz von England?”“Geh zu einem Spezialist!”Strictly speaking it is “incorrect”, but since languages are organic and constantly changing, it may just be a matter of time before the “n-declension” will be fully extinct. Until then I’d advise you to keep in mind that it exists but not be overly worried about it.

–

The post “I Can’t Get No …”: N-Declension In German appeared first on LearnOutLive.

“I Can’t Get No …”: N-Declension In German

Welcome back to another instalment of our German grammar series in which I answer some of the questions that have popped up on the newsletter. Today’s question is by Douglas:

My question: why do some German nouns add a final ‘n’ in the acc. sing., e.g. ‘meinen Namen’ , einen Geldautomaten, which, of course has to add -en, since the nom. ends in ‘t’. Is there a rule that governs this, and if not, is there a list of offenders one can just learn!

Rule Of The Weak

First of all, these nouns belong to the group of the so called “N-Declension” and are also called “weak nouns”. But before you start wondering whether these nouns are in need of some serious gym time or protein shakes, let’s look at their basic characteristics:

Weak nouns …

are always masculine

get an additional -n in their Akkusativ, Genitiv and Dativ declension (in singular!)

In other words: not all masculine nouns are weak nouns, but all weak nouns are masculine*. In the case of Douglas’ question, Geldautomat is of course masculine (der Automat).

Let’s have a look at some examples:

Ich habe diesen Namen noch nie gehört. [Akkusativ – der Name]

Das ist der Film des neuen Produzenten. [Genitiv – der Produzent]

Sie hat dem Jungen Komplimente gemacht. [Dativ – der Junge]

As you can see all these nouns are masculine and they receive an additional -n in their Akkusativ, Genitiv and Dativ (singular) declensions.

In plural their declension endings are identical. In fact, you only know that they are plural because of the article. Let’s run through the same three examples again, but see how we switch to plural (article colored turquoise) and the declension stays the same:

Ich habe diese Namen och nie gehört.

Das ist der Film der neuen Produzenten.

Sie hat den Jungen Komplimente gemacht.

List Of N-Offenders

The amount of nouns belonging to this group of “n-declensions” is relatively small, but there are some patterns for spotting them, aside from being masculine.

Many of these nouns end on -e, -ent, -ant, -ist, -oge or -at.

Mostly they describe nationalities, persons or animals

Let’s have a look at some of these:

Nationalities:

der Deutsche, der Russe, der Franzose, der Pole, der Türke, der Rumäne, der Afghane, der Bulgare, der Ire, der Schotte, der Chinese, der Schwede, der Finne, der Däne, etc.

Examples:

“Ich kenne diesen Franzosen aus dem Fernsehen.” (Akkusativ)

“Das ist die Tochter des Polen von nebenan.” (Genitiv)

“Ich werde mit dem Afghanen sprechen.” (Dativ)

Persons:

der Spezialist, der Journalist, der Polizist, der Christ [-ist]

der Produzent, der Präsident, der Agent [-ent]

der Intendant, der Leutnant, der Informant [-ant]

der Virologe, der Urologe, der Pädagoge [-oge]

der Bürokrat, der Aufsichtsrat, der Apparat, der Soldat [-at]

“Ich mag diesen Bürokraten nicht.” (Akkusativ)

“Die Arbeit des Polizisten ist nicht leicht.” (Genitiv)

“Sie gibt dem Agenten die Papiere.” (Dativ)

Animals

der Elefant, der Affe, der Löwe, der Hase, der Ochse, der Bulle, der Rabe, etc.

“Ich finde diesen Affen lustig.” (Akkusativ)

“Das Leben eines Löwen im Zoo ist traurig.” (Genitiv)

“Sie geben dem Hasen Futter.” (Dativ)

*Exceptions

As always with grammar, there are exceptions. Here are some words that are part of the group of “weak nouns” but don’t necessarily fit into our previous categories:

der Architekt, der Chaot, der Held, der Fotograf, der Herr, der Bauer, der Pilot, der Prinz [masculine persons, but not ending on -e, -ent, -ant, -ist, -oge or -at.]

das Herz [the only non-masculine weak noun]

der Automat, der Diamant [masculine nouns ending on -e, -ent, -ant, -ist, -oge or -at, but not nationalities, persons or animals]

der Bär, der Fink, der Spatz [masculine animals, but not ending on -e, -ent, -ant, -ist, -oge or -at]

A Dying Breed

So many rules, so many exceptions. Yes, but before you despair, I have some good news: the “n-declension” is almost extinct in colloquial German, i.e. you will hear people leave out the “-n” all the time in daily life, especially in Akkusativ and Dativ. It’s very common to hear people say things like:

“Frag den Pilot!”

“Kennst du den Prinz von England?”

“Geh zu einem Spezialist!”

Strictly speaking it is “incorrect”, but since languages are organic and constantly changing, it may just be a matter of time before the “n-declension” will be fully extinct. Until then I’d advise you to keep in mind that it exists but not be overly worried about it.

–

The post “I Can’t Get No …”: N-Declension In German appeared first on LearnOutLive.

August 21, 2020

New: Dino lernt Deutsch Episode 11: “Lockdown in Liechtenstein”

The wait is finally over! Dino is back, and although his world has gotten a lot smaller, he still finds himself at the center of much mischief. Get volume 11 on:

July 30, 2020

Demonstrate This! – Demonstrative Pronouns in German – A Brief Overview

This is another instalment in my grammar series where I try to answer some of the questions posed by readers of my newsletter and (hopefully) shed some light on certain bewildering grammar topics, always with a practical focus on how people actually speak. Here’s today’s question, by Myron:

“Would you explain all that which is “Demonstrative” in German grammar, and especially, the use of “dies” as opposed to the likes of “dieser, diese, dieses” and so on.”

What are Demonstrative Pronouns?

They are “demonstrating”, i.e. “pointing” at something

They are stand-ins for nouns (“pro nouns”)

In English the demonstrative pronouns are this, these, that, those. The first two “demonstrate” things which are closer to the speaker, the latter two those which are farther away.

“This cat is hungry.” – pointing to cat close to speaker

“That cat is thirsty.” – pointing to cat farther away

The German equivalent is: dies(er/e/es), diese, jen(er/e/es), jene

“Diese Katze ist hungrig.” – closer

“Jene Katze ist durstig.” – farther away

While this is strictly speaking the correct usage in German, most speakers will just use dies(er/e/es) regardless of distance, since jen(er/e/es) sounds somewhat stilted.

While this is strictly speaking the correct usage in German, most speakers will just use dies(er/e/es) regardless of distance, since jen(er/e/es) sounds somewhat stilted.So, it’s actually pretty straightforward. The real complexity comes due to the different endings (declensions). Let’s have a look at the full gamut:

.tg {border-collapse:collapse;border-spacing:0;font-size:95%;width: 100%;}.tg .tg-0lax{text-align:left;vertical-align:top}.green {color:#339966;}.blue {color:#0000ff;}

case

singular

plural

male

female

neuter

Nominativ

dieser Kater

diese Katze

dieses Kätzchen

diese Katzen

Genitiv

dieses Katers

dieser Katze

dieses Kätzchens

dieser Katzen

Dativ

diesem Kater

dieser Katze

diesem Kätzchen

diesen Katzen

Akkusativ

diesen Kater

diese Katze

dieses Kätzchen

diese Katzen

If you’re already familiar with basic declension endings in German, then this shouldn’t seem too difficult. These endings for demonstrative pronouns are exactly the same as when using personal pronouns, i.e. der/die/das.

The other forms jen(er/e/es), while somewhat rare in colloquial use, follow the exact same pattern. I’m listing them here for completeness’ sake:

case

singular

plural

male

female

neuter

Nominativ

jener Kater

jene Katze

jenes Kätzchen

jene Katzen

Genitiv

jenes Katers

jener Katze

jenes Kätzchens

jener Katzen

Dativ

jenem Kater

jener Katze

jenem Kätzchen

jenen Katzen

Akkusativ

jenen Kater

jene Katze

jenes Kätzchen

jene Katzen

Personal Pronouns as Demonstrative Pronouns

There are a number of other forms of demonstrative pronouns in German (see here for a full list). However, one of the most important ones for daily life is the following: using personal pronouns as demonstrative pronouns. Say what? It’s actually less confusing than it sounds.

This variety is often used to prevent repetition of a noun or to emphasize it. These emphasized pronouns are often seen in position 1. Here are some examples.

“Hast du Sarah gesehen?” – “Die habe ich heute in der Stadt gesehen.” (I’ve seen her in the city.)

“Wo hast du den BMW gekauft?” – “Den habe ich in München gekauft.” (I bought it in Munich.)

“Wo hast du denn die Katze her?” – “Die habe ich aus dem Tierheim.” (I got it from the animal shelter.)

“Wie findest du Peter und Sarah?” – “Von denen will nichts mehr hören.” (I don’t want to hear from them.)

case

singular

plural

male

female

neuter

Nominativ

der

die

das

die

Genitiv

dessen

deren

dessen

deren/derer

Dativ

dem

der

dem

denen

Akkusativ

den

die

das

die

As you can see there are some deviations from the regular personal pronouns here (marked in orange) specifically in Genitiv and Dativ (plural). Here are some examples.

“Wo ist eigentlich Peter?” – “Ich weiß nicht. Dessen Vater habe ich gestern gesehen.” (I’ve seen his father yesterday.)

“Hast du den Müllers die Einladung gegeben?” – “Denen habe ich die Einladung noch nicht gegeben.” (I haven’t given them the invitation yet.)

These forms are highly prevalent in colloquial use. And yes, they are a bit tricky to learn and you don’t have to use them yourself, at least in the beginning, but it’s certainly helpful to understand the patterns early on.

Another thing that may be confusing for native English speakers is the difference between “dies” and “das” which can strictly speaking both be used where an English speaker would use “that”.

Example:

“Did you know that?” – “Hast du das gewusst?” / “Hast du dies gewusst?”

“I didn’t see that.” – “Ich habe das nicht gesehen.” / “Ich habe dies nicht gesehen.”

I say “strictly speaking”, because in most cases using “dies” sounds awkwardly stilted.

As a general rule of thumb, whenever you find yourself wondering whether to use dies (without ending) or das, just pick das.

As a general rule of thumb, whenever you find yourself wondering whether to use dies (without ending) or das, just pick das.Here are some good exercises to practice the most common forms of demonstrative pronouns from Toms Deutschseite , one of my favorite worksheet resources:

Demonstrativpronomen 1 / Answer Key

Demonstrativpronomen 2 / Answer Key

–

The post Demonstrate This! – Demonstrative Pronouns in German – A Brief Overview appeared first on LearnOutLive.

July 8, 2020

Learning Languages With Netflix Has Just Become So Much Easier

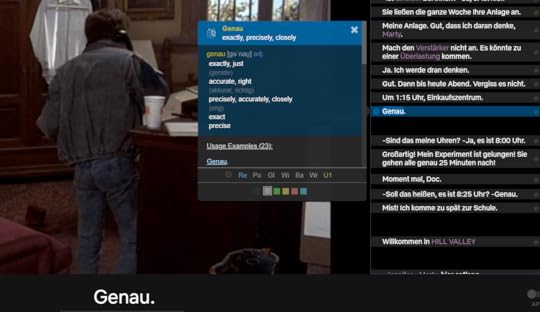

Many language learners are watching movies to improve their listening comprehension and pick up new words. Some like to just immerse themselves in the foreign language with foreign subtitles, others watch it with foreign audio and subtitles in their native languages, but no matter how you’ve been doing it, learning German (or any language for that matter) with Netflix has just become a lot easier thanks to this ingenious free Chrome Extension.

The extension is called Language Learning with Netflix and it allows you watch movies with two different subtitles simultaneously and get instant translations when hovering over words! There are a number of other features, but its’s these two that are at the heart of this extension.

How does it work?

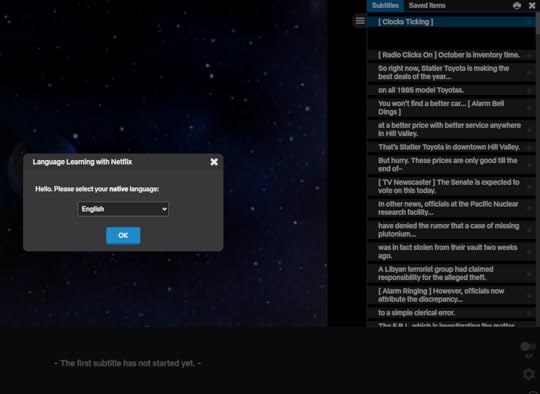

First of all, head to the Chrome Web Store to download and install the extension. Then open Netflix in your browser and open a movie. You’ll be greeted by a screen asking for your native language:

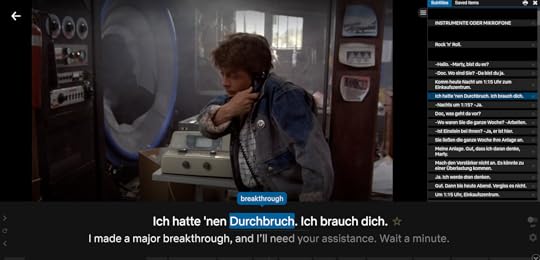

For the sake of this example, I’m using “English”. Once you’ve selected your language, click “ok” and you can start watching the movie. You’ll notice immediately that the layout has changed. The Chrome Extension shows you a sidebar on the right with all of the subtitles neatly separated into digestible phrases. Now you can change the subtitle language (as you’d usually do) by clicking on the Netflix subtitle icon. For the sake of this example, I’m using German:

As you can see we now get two different lines of subtitles, with my target language (German) on top and my native language (English) below. When you now hover over words, you get a little popup bubble with the translation. No need to open a new tab or type words into a dictionary. It’s seamless and nearly perfect.

You can also click on the subtitle phrases in the sidebar to get additional information, usage examples, text-to-speech (pronunciation) and switch dictionaries:

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. You can do a lot more with this extension. Here’s just a quick overview of additional features:

automatically pause playback after each phrase (disabled by default)

print out all the subtitles of the movie with side-by side translation (great for review or using in class)

powerful keyboard shortcuts (S or arrow down for repeat, toggle auto-pause with q, etc.)

change playback speed (not perfect, but very workable)

use your own custom dictionaries for lookup (For example, paste “https://www.dict.cc/?s=” in there to get dictionary results from dict.cc or any other dictionary)

save or “favorite” subtitle phrases to your private dictionary (pro feature, haven’t tested it yet)

In short if you’re a language learner and avid Netflix watcher, this extension is a game-changer. Have you tried it yet? What are your thoughts? Let us know in the comments.

–

The post Learning Languages With Netflix Has Just Become So Much Easier appeared first on LearnOutLive.

April 29, 2020

When Learning Online Is The New Normal

When I quit my teaching job more than ten years ago to strike out on my own as an online language teacher, I was met with stares of consternation. Old acquaintances warned me of the perils of pennilessness and urged me to re-enlist in the federal education system. Online learning? Why, that’s just a fad, young whippersnapper …

But I had seen enough disillusioned teachers and underfunded schools for a lifetime.

So I handed in my notice and ventured forth, equipped only with a ragtag skillset of self-taught coding and a dream of a new streamlined way of learning and teaching.

Within a few months I was holding classes online from morning until evening. The proof was in the pudding. I had students from all over the world, both kids and adults. They made significant progress and kept coming back for more. Learning online was both intimate and liberating, highly focused and time-efficient.

This was all before the total proliferation of smart phones and social media, mind you, before increasingly organized astroturfing and political propagandizing gave the online world a bitter aftertaste.

The Online Learning Revival Of 2020

My point is that the possibility of learning online effectively has been with us for more than a decade! It’s not exactly novel. So it’s somewhat amusing to now see educators and education ministries all over the world stumbling into all of this completely unprepared due to the pandemic. Unfortunately online learning is still an alien concept to so many people.

And sure, remote learning will never be the be-all and end-all to all educational needs. But it turns out that when faced with the option of learning/teaching online instead of nowhere at all, people are suddenly surprisingly open to the idea.

Personally, in an effort to make the most of this lockdown, I’ve been joining a number of new online seminars and lectures over the past few weeks (Zooms, Livestreams and AltspaceVR meetings), and while some teachers initially had called online meetings into existence as a replacement for now defunct physical venues, many of them have expressed plans to continue these types of meetings even after the pandemic would be over, especially after seeing participants’ positive responses.

In other words, we’re experiencing a sort of revival of online learning in these strange times. And the biggest breakthroughs aren’t necessarily happening in institutions which are sometimes too entrenched in the status quo, but it’s individual teachers’ private initiatives setting up livestreams and online meetups that often feel most genuine and rewarding.

So in the spirit of all of this I’d like to share some resources today for everyone interested in expanding their own online learning and teaching efforts.

How To Start An Online Book Club

I often receive emails from people who read my German learning books together in small groups meeting in cafés, libraries etc. Many of these venues have now closed due to the virus, but that doesn’t mean that your learning group can’t continue online. I’ve briefly outlined here how you can move your book club or study group online without skipping a beat.

LearnOutLive Online Teachers Directory

If you’re looking to use the extra time at home to work on your German skills with a tutor, take piano lessons or brush up on your organic chemistry, the LearnOutLive teachers directory lists hundreds of independent online teachers and tutors from all over world. If you’re a teacher yourself, feel free to add a link to your own website! You can also answer our short interview and get featured on the blog. Or join our forum to talk with other educators.

How To Teach Online Without Selling Your Soul

In 2012 I released a book in which I collected everything I had learned while setting up my online teaching business. While some of the technical details are admittedly outdated now, much of the general advice still applies and you can download the book for free here if you like.

–

The post When Learning Online Is The New Normal appeared first on LearnOutLive.