Meg Sefton's Blog, page 78

July 1, 2015

Five Flashes from DEAR PETROV by Susan Tepper

June 9, 2015

The Baby Justice League of the Undead at Asylum Ink

Visit the horror site Asylum Ink to read my piece “The Baby Justice League of the Undead,” just out. It would be great if you felt inspired to post a comment there. I hope your summer is off to a good start.

photo by Golden Cratalo

May 25, 2015

Instructions for the Ascent: A Guide

anna Osu’s “walking on water,” flickr

Shuffle through the silent wood to worship, past loblollies and scrub oak hung with flowering vines, your sick feet, affected by the chemo, the nerve endings numb, barely registering your footfalls. The glittering lake beckons beyond the Bishop’s Walk and the Church of the Incarnation where someone sits at a piano, someone mixes water with wine, someone is blinded by the sun streaming through a window as they think about what they would like for dinner.

Step high over roots, concern yourself not with the sand slipping between your toes, breaking down your best sandals. Enjoy the sand and how it falls out of your shoe in a playful way because you cannot walk because of your numb feet and it is as if you are doing this on purpose, like when you were young and flopped your legs in front of you, flinging sand on your brother, on your sister, and you had more time then, all the time in the world.

It doesn’t matter you are late. You have nothing to contribute. There will always be voices in worship somewhere. There will always be worship. Not even the forest needs you though it will take you. There will always be bodies who, once animate, return to earth and you, no longer a child, see how it begins as you fall off out of time beginning with the feet that can no longer run, the flesh that is no longer thought of or desired by those in time, and you, having once participated in a chorus, live on an edge without recognizable features or breath, where eternity has caught up with you and you had thought yourself not ready and yet here you are, venturing on your own.

Those you thought should join you cannot follow through the divide, they cannot pass. You have tried to carry them but the overwhelming nature of their fears have led you to focus instead on the little white dog who waits for you on the edge of town, the new ferns that must be watered, the meals you will make with the ingredients you just bought at the market, the son who will be home from his father’s next week.

In the twilight worship hour, you must go alone through the loblollies and scrub oak hung with vine, the sparkling lake in the distance, until you reach the lip of it all, where the worshippers’ voices coalesce and become strongest, like a ring of sound around the world. And yet, you only see the glittering eye of the abyss in the distance and it is not in the depths of the earth but suspended and it is not dark but filled with light and fills the skies from the waters it takes from earth and one day you will be taken up from the earth and one day you will return again as rain.

Published in Ginosko Literary Journal #16

May 8, 2015

May My Father Rest

Photo: William Hanly’s Wolf and Child

When they come to capture Father, they do so with ropes and sticks and feed him bear containing a tranquilizing substance. We watch as he devours the flesh, its blood resting in the fur I use to kiss. He had been starving and��in mourning for my mother, who had been captured, tagged,��and taken away to higher regions. My brother and sister and I do not make it obvious to him we could see his defeat. We eat our grains and cream in silence in cupboard spaces and we do not crowd him or come near.

The men hoist him onto a stretcher, their pipes set in their teeth, the smoke from the bowls drifting down over our father’s limp frame, as if he were powerless, as if he were lazy and never chased deer and wild game, as if he had not laughed at our games in sunshined fields and watched for danger along the shadowed edges.

I touch his paw as his body moves past and it seems as dead and yet it has steadied me while I took my first steps. With it, he has lifted me onto his back where I would ride holding onto his fur, the nape of his neck smelling of��burnt wood��and leaves.

My brother and sister are calling out for my father, my brother and sister are crying. It is the new people who do not understand, I say, though I know my brother and sister, being young,��do not know my meaning. I have no words of comfort for them while the presence of the men lingers heavily in the air. Drink your milk I say and they drink the heavy milk at the bottom of the bowl, the last of the milk my father stole from the farmer further down in the valley.

I am not ready to speak for my mother and father both. I am not ready to guide.

I take them out to play where they can run among the stones of the people who have died. They should not have to watch as their father’s body jars as if lifeless on the open-bed truck while men’s ash falls on his fur.

I tell them these are the stones commemorating all who have returned, though I know they will not believe this in the literal sense I wished it to be understood. And yet it comforts them, children of tombstones and loss, that in some sense, this is true, and that even men with stiff lipped bearded faces have no say in what cannot be contained, or shot, or beaten.

And when the sun is high we take a picnic on the stones and when it rests over the mountain range we lie among the memorials to people who were and wait for the chorus of animals that contains the voice of our mother penetrating the mists of the dreaming dead.

First appeared in Chrome Baby

May 1, 2015

The Man Who Loved a Grave

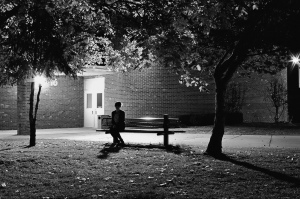

photo: Ambiance��by Jacques

Katya ran her finger over the round warm ceramic of the coffee mug. She had to admit to herself it was a comfort to have this portion of her life, her life with Nina, finished. Though just as soon, she was horrified. Her friend had died an awful death – sick from cancer, alone except for Katya with whom she split rent, estranged from wealthy parents, divorced, the mother of one selfish daughter who hardly visited. Katya believed herself to be a terrible person for thinking about her own relief.

In a silly moment, Nina had asked Katya to pour a cup of coffee on her grave at least once a week, maybe more, for as long as she was missed, then Katya was to be free of the routine. They drank bottomless coffee at a diner during mornings they worked in the shops on Park Avenue, during the days Nina was well. Nina also asked Katya to burn a letter that she had written out and placed in her jewelry box. This act of the burning seemed a bit more serious than the coffee ritual, and yet both involved performing an act over her friend���s grave. Nina made Katya swear not to look at the letter before the burial.

One day after work, Katya stopped by Nina���s grave. She pulled Nina���s letter from her purse. It was in an envelope, sealed, and written on several sheets of small square pink papers, the stationary she started to use near the end of her life to make out grocery lists and requests for Katya. It read:

Dear Katya,

You have been my sole confessor in these last few years and on you has fallen a great burden and for that, I’m very sorry. Had I allowed myself to entrust my worries and cares to anyone else, I would have. Maybe it was the illness that stirred up fear in me but in my growing physical weakness, I could not always trust others to be as tender with my heart. People are a bit like animals in this sense, especially when there is a sick person among them. But you, dear Katya, have been more than humane.

I am scared of dying, because of bitterness I have inside, bitterness I fear will keep my spirit wandering. I am scared of my sins. I am scared of the reality of the woman I’ve been, the woman I fear my daughter sees and the woman God has punished with disease. Therefore I have left this one task up to you, to burn this list of the things I have held onto in bitterness along with the sins I have committed. Please leave no corner of these papers intact, but burn them wholly over my grave and let the cinder mix with the soil and be my penance, my last confession. I’m not Orthodox, as you know, I have no priest. Please, dear Katya.

Forever yours,

Nina

It rained the morning Katya intended to burn the papers. She was so surprised by the fervor of the note and the length of the list. She sat out beside her grave longer than she had anticipated. Her coffee grew cold. She fed the grave what was left of her drink, but it was too wet to burn the papers. After work that night she sliced vegetables and brought water up to a boil in their lonely apartment. She ate dinner and watched TV and went to bed but felt in the moments before sleep a presence watching from the corner of my room. Was it Nina?

She was able to burn the list of Nina���s sins the next day and prayed that her soul would be released from the burden of the guilt she felt, from her bitterness. And yet she noticed as she burned the paper, the soil was dry as if from drought, even though it had rained through the night. She bought a watering can and from that time on, watered Nina’s grave every day. To no avail. It drank in every drop of water fed to it and produced nothing. It lay barren as the day she was buried. No grass grew. No flowers that were planted there would thrive. Had she missed some opportunity to make things right for Nina that first morning she sat beside her grave, procrastinating until it rained and it was too wet to burn her letter?

Several years later she met Nina’s daughter. The young woman came to the apartment to find out how things had been for her mother during her illness. Katya revealed the mystery of the gravesite. She was careful with her description of the letter.

“I’m sure my mother was upset I never called or came to visit,” said the young woman.

Katya remained silent.

“I will try to water her grave. Maybe it will work for me.”

The grave did not respond to the daughter’s ministrations.

Again, Katya felt the intensity of a presence in the corner of her room that evening.

She decided to write to Nina’s parents and friends and ask them to visit. Upon their arrival, they knelt beside the grave, tending to the soil, but the plot of land rejected their efforts.

Perhaps there was something perfunctory about how they went about things, Katya considered. Perhaps this was the difficulty. She did not know how to change this since likely there were so few who truly loved tending a grave. And sadly, few truly seemed to love Nina. The cause of this seemed to have nothing to do with Nina herself. It was just her fate. Any grave tending would be perfunctory. Even Katya had not been the friend Nina needed.

One night a man knocked on the door. It was New Year’s Eve. Katya was not going out and had not expected anyone. She did not feel the festive spirit.

The man, she noticed, had skin as white and translucent as parchment. His hair was a soft yellow.

“I have come to pay my respects to Nina.”

When Katya told him the plot number, he watched her with his clear blue eyes, a blue she had rarely seen.

She went back to Nina’s grave before heading to the shop a couple of days later. A profusion of lilies grew there from soil as rich as loam.

The only thing Katya could figure in the weeks following, as flowers continued to bloom there, in the space where an unregenerate woman lay, is that someone loved Nina, someone her friend had not remembered during the torturous months of her illness, or there was someone alive whose love, until then, had remained undeclared.

First appeared in Quail Bell Magazine

March 29, 2015

salt-rose

Photo: Aku no musume by Anna Theodora

Pablo Neruda: XVII (I do not love you…)

I do not love you as if you were salt-rose, or topaz,

or the arrow of carnations the fire shoots off.

I love you as certain dark things are to be loved,

in secret, between the shadow and the soul.

I love you as the plant that never blooms

but carries in itself the light of hidden flowers;

thanks to your love a certain solid fragrance,

risen from the earth, lives darkly in my body.

I love you without knowing how, or when, or from where.

I love you straightforwardly, without complexities or pride;

so I love you because I know no other way than this:

where I does not exist, nor you,

so close that your hand on my chest is my hand,

so close that your eyes close as I fall asleep.

March 11, 2015

Murderer in The Ice Hotel, Jukkasjärvi , Polar Sweden

There is a murderer staying in the ice hotel. He sleeps on his ice bed which is covered in reindeer fur. He drinks Absolut vodka from a frozen shot glass. He cries to the walls made of the clear, pure, bubble-free ice harvested from the nearby Torne River. The snow cementing the ice block muffles his grief. It absorbs what he cannot bring himself to say: He killed his girlfriend when he caught her with another man.

The ice in his room shifts, sighs, drips. It is April 6, the end of the season. A dripping snow column beside his bed pulses with muti-colored LED lights, He is calmed by this, this lifelike column a beating heart, a gentle mother watching over him as he lies upon his bed. He finally falls asleep in a room that is twenty four degrees fahrenheit.

The next morning, the murderer goes on a tour to meet the indigenous people, the Sami or “reindeer people.” A group of men taking the tour are hung over and worried about getting to Heathrow. They make fun of the guide who fries reindeer meet before the fire in his ancestral tent. The guide tells them about his culture and the men ask him where he gets his clothes and the guide says his mother sews them. “Oh,” says one of them. “I would have said Saks.”

There is a woman with them too but she watches the fire intently. After they have eaten, they ride in sledges behind reindeer. The men are thrilled with the bull who is so fast pulling each of them, they are tossed into the snow. The woman quietly rides in her sledge behind a cow. The murderer takes over her sledge when she is finished and doesn’t mind the pace.

He wonders if he could escape to this place, ingratiate himself among the people, learn the language, tend the herds. He wants to live among the reindeer with their large brown, wet eyes. Could he escape into the wilds of Lapland, where in winter the temperatures hovered around zero and snow would not be shared with another for miles? He could change his name, adopt their belief in an animated world, exact his own punishment or wait for it to come.

As it stands, the ice hotel is melting. Soon it will no longer be structurally sound. He buys equipment in Jukkasjärvi and a pack of dogs using the remaining money in his account. The trees stand around him like thickly frosted decorations on a thickly frosted cake. He sets out on his sled, making his mark upon the snow, a mark that will be gone when the snow falls again that night, a wet spring snow but a blanketing one. Even the hotel will melt into the Torne River and be resurrected the next winter with no traces of anyone having slept there before.

* Some of the details regarding the hotel and tour are loosely based on Barbara Sjholm’s beautifully written travelogue The Palace of the Snow Queen: Winter Travels in Lapland.

March 5, 2015

under no circumstances conform

February 27, 2015

The Steinway

(The formatting is off in places. The cut and paste of a long-ago story didn’t work so well technically. I will type it up again tonight if I have another round with my new best friend: insomnia.��Or maybe I am simply��becoming nocturnal and am on the road to accepting it.�� Nonetheless,��in the meantime,��I hope you get the idea. Apologies and thanks for reading.)

I found the Steinway on the internet. It was dull, black, the paint rubbed off on the corners, a few scratches here and there. The logo was written out in gold letters below the emblem of the pedal lyre.

It arrived on a hot October Florida day. It was shrouded in a faded purple quilt and sat upon a wooden platform that shushed and squeaked as the movers wheeled it across the carpet. When lowered to its place in the front parlor, it exhaled a breath of discordant notes. I struck a key and a string responded in a tired way. I struck the C major chord, the only one I remembered from my childhood, and a cacophony of complaints issued forth, the notes warping and wavering. I began to doubt my earlier certainty that it was fate that I should have this dusty instrument in my house, that I should have it tuned and should learn how to play. My current mid-life desire to try again that which had eluded me as a child was perhaps another incarnation of all that was wayward and impractical and ridiculous in me.

It was getting dark. No one was home. I had arranged for the kids to go to their friends��� houses after school in case the piano was delivered late. I had an hour to listen to the blade of my knife slice through the flesh of vegetables, to get the water up to a boil, to open wine. My wife Lena was an attorney with a prestigious law firm in Orlando and often worked late. I sold real estate, but recently, the market had slowed. On my worst days, I felt outstripped but often managed to convince myself that the children needed me. I had bought the piano to keep myself occupied through the lull though we could scarcely afford such an indulgence. At least I had bought a relatively inexpensive upright. That���s what I told myself.

Because I was home more and Lena worked late, my tasks were to shop and make meals, to pick the children up after school and secure their clothing and school supplies. Emily, our eleven year old, was a budding ballerina, and Giles, nine, liked sports, almost any sport, but he liked it in an easygoing, rather than competitive way. Emily was her own self-disciplined being, and reminded me of her uncle and mother both. My brother had succeeded at the piano and I often told her Uncle Edward would have been proud to have seen her dancing to many of the musical pieces he had learned to play. This seemed to please her and she smiled with her mother���s beautiful mouth and her mother���s green eyes sparkled back at me. She often gave me a hug because she believed I was sad when I mentioned my brother. By now, she knew he had suffered anxiety and depression and had experienced recurring physical pain in his hands. She knew he had died of an overdose of painkillers. Though my brother had died in this way, I knew him to be the greater man, and I���ll admit a part of me was glad he was not alive to prove it.

When Lena got home and saw the changes I had made to accommodate the piano, she registered her protest. ���You have moved the sideboard under the window. That���s not a good place. It���s about a million miles from the dining room table.��� We had a large front room that accommodated both a dining room and living room area. We had never been able to agree upon the division and arrangement of tables and chairs.

���I made chicken. I think you���ll like it.��� I handed her a glass of chilled white wine. ���Try this Pouilly Fuisse.���

���The lamp you put on it doesn���t go. It���s not a lamp for a sideboard.���

���You can get us another.��� I took the wine from her and slid my hands over the silk of her blouse. I felt the metal clasp of her bra.

���That piano is hideous.���

���Where is Lena?��� I said, and kissed her on the cheek. It is a game we used to play when we were first married and I believed myself capable of loosening her to laughter, to good humor.

���I don���t think this is going to happen, not now.���

I pulled her to me and kissed her full. I felt with my fingers along her neck and shoulders, searching for the places I knew were sensitive.

���The kids will be coming soon,��� she said, turning, bowing her head.

���It���s OK,��� I said. I put her on the counter and entered the space between her legs.

She pushed against my shoulders and eased herself down to the floor. She seemed weaker, more diminutive, without her heels, her stockinged feet flat against the tiles.

When my lessons began, I came home from work during my lunch hour to practice. I began to like the freedom and solitude to work as slowly as I needed to. One afternoon, as I was playing a scaled down version of a Chopin piece, composed for beginning students, I detected movement on the porch. ���Come in,��� I said, from my bench, certain it was someone we knew who was politely waiting until I finished playing to ring the doorbell. It was Carrie Stewart from down the street. Her family and mine had been a part of each other���s lives for many years, and in fact Lena and Carrie���s husband, Gray, had gone to high school together and were now working for the same law firm.

���Can I listen?��� she said.

���Sure. But there���s not much going on. A whole lot of bad playing, I���m afraid.���

She sat. She chose my grandmother���s channel back chair. This had always been a favorite of mine, but I was determined not to comment, to engage in conversation. If this was how she saw fit to waste an hour, I would not make myself responsible for her entertainment. I resumed played my scales and simple pieces. I remembered my brother, his back erect, and as he grew, his shoulders broad, his body a square within the larger square of the piano, his fingers working through the lines, stumbling, repeating, slowing, then smoothing the line down like a brook works over a pebble.

Carrie maintained her place behind me at the same time every day, slipping out at some point near the end of the hour. Maybe she waited on the porch until I was finished, until she heard me shut the music back into the piano bench. The vain part of me wanted to believe this.

One day, after several months of attending my practices, she rose and stood near the piano. I stopped playing. She let her fingers drift over the keys. ���It takes so much faith, to do what you���re doing��� she said. ���We know what our lives are by now.���

���I���m just playing scales.��� I took care not to look at her, to not make contact. She should not read too deeply into anything, must not read anything at all.

���You don���t have to do all this. I think it���s wonderful.��� And she left, closing the door behind her softly as she did every day.

I didn���t want to ask her what she getting out of listening to scales and something dull and repeated over and over, until mastered. For once in my life, something as intriguing as a woman was concentrating my energies, moving me through my day.

And yet, her presence there, day in and day out, was liberating my performance. When I made so many mistakes, especially when I was first learning a piece, her lack of response, her lack, even, of a sound, was confirmation that mistakes were not as terrible as I had believed them to be when I was a boy.

One day I thought it might be a good idea to clarify things. I turned to her. She was working on her needlepoint.

���I don���t think it would be a good idea to make too much of this here,��� I said.

���What do you mean?��� She looked at me with an even gaze and yet her lids had fluttered when I spoke, either at my tone or her surprise at what I said, or maybe just the surprise of the break in our usual routine.

���I mean that something might happen between us.���

She bent her head to her work. I watched her find the place for her needle. Her composure held.

I was absolved, I told myself, and continued to play. I wouldn���t broach the topic again.

As time went on, I began to practice longer and longer into the day I found ways to adjust my schedule.

After a while, when I took a break to stretch or get a snack, Carrie would tell me she suspected her husband Gray was having an affair with my wife. It had been customary for us to have them over every other weekend or so while our children stayed with the Stewart���s babysitter. In the last year, I noticed Gray had become more proprietary with Lena as we sat together at our kitchen table. The two of them would tell inside jokes about the firm where they both worked. They flirted and nudged each other, their faces, their gleaming smiles, hovering together, close. When this first began happening, I would slip into the role of an observer, frozen in my anger and alarm, plotting what I might do if Gray should take it further. Carrie would slip out to our living room, which was quiet and formal in a way that might have been comforting. I avoided following her, although I knew I would rather avoid this exchange at my own table. I stayed instead, feeling my presence there was essential. If I kept the topic on high school reminisces, Gray would be gone soon, purring out of the driveway in his Porsche, his wife tucked away in her bucket seat, buckled down.

And then, things started unraveling. It was the drink, most likely, and we all, except Carrie, began imbibing as if the world was going to curl up and swallow us whole.

I began to slip away to play the piano while Lena and Gray amused each other. Carrie would follow me, bringing her needlepoint. She would bring it in her purse as if she anticipated a need for it. At some point, I gave up my role as observer, protector.

I considered the possibility that my wife may be baiting me, that she wanted a reaction. If so, I disappointed her many times. I wanted to ask Lena directly about her involvement with Gray, but dreaded the possibility that she would lie. I tried to believe their banter was nothing but a game, or, if it went further, it was something Lena would get over like a bad virus.

Late at night when she was asleep, I began checking through her purses and briefcase and clothing for evidence. When I had tired of my search, I sat before the Steinway and laid my hands on the keys, their enamel off-white surfaces like teeth. I imagined myself playing as I moved my fingers through various chord progressions.

���What are you doing?��� said Lena, finding me one night in the dark, sitting before the piano. She snapped on the overhead light.

���I think it���s obvious. I���m laboring in obscurity.���

���It���s three in the morning.���

���I couldn���t sleep.���

���You never sleep.���

She retied the sash of her robe. What I had loved about her was her use of extremes, to see only ���never��� and ���always.��� I had considered this a sign of passion. What I had come to realize was that she had an unwillingness to admit that adversity was usually not a permanent condition. Her pronouncements on the state of things were informed by whatever her needs were at the present moment and she had little patience in waiting for tides to turn.

���I���m going to warm some milk,��� she said, retreating to the kitchen.

���Want some?��� I followed.

She poured milk into a saucepan and turned up the fire on the eye. She stirred it until it steamed and then poured it into two mugs and added some sugar. She sprinkled some cinnamon on top. She had created this drink for my insomnia, using the ingredients her mother used to add to her cream of wheat, but tonight she stirred roughly and slung the spoon into the sink. I had learned that small things such as her careless handling of a utensil, the closing of a door just a bit more firmly than usual, the whip of a hot sheet fresh out of the dryer ��� that these all meant something, and that it was my job to figure out what that meaning was.

���You are upset about something,��� I said.

She put her half-empty mug in the sink. I reached out and felt the silk of her nightgown peeking out from under the robe.

���I���m not sure this is the time, but yes. I���m upset Richard.��� She leaned with her hip against the edge of the counter. ���I���m worried. I���m worried about how much money we need, and about how crazy it is you���re spending so much time on that thing in the living room.���

���We���re just in a bit of a dry spell.���

���We���re always in a dry spell. Emily needs braces and we need the porch fixed. I���m embarrassed to have friends over now because a part of it is sagging. Summer camps need to be paid for, next year���s school tuition.���

���It will work out, my love, you���ll see.���

���I feel overwhelmed and you just seem so calm. I don���t know what to say anymore.��� She whipped past and I made an attempt to grab her arm, to draw her to me and assure her, but her body eluded me.

I climbed the stairs to our bedroom. ���Lena,��� I said, when I had closed the door. It was dark and she was already under the covers. ���I need to know something, and I want you to be straight with me.��� I sat on the edge of the bed, bracing myself.

In the shadows I saw her rise up from her pillows.

���Are you having an affair?��� I said.

���What?���

���You would tell me, wouldn���t you?���

���I���m not sure I know what you���re saying, Richard, but I think we���re past the point of talking about anything. I would just like to get through the night if that���s OK.”

She lay down and covered herself, covered her face and hair. I stood over her, wanting to rip away the things that separated us.

She tossed the covering away from her face. ���What you���re doing here is projecting.���

���What do you mean?���

���I know she comes over here.���

���Nothing is going on,��� I said, standing. ���Nothing.���

���I have a really big case tomorrow.��� She arranged her pillows and settled back into them. ���Please.���

I slept on the couch that night. The next day, I had a call to make at Claudia Pinza���s, my piano teacher. When I pulled up to her antebellum mansion on Princeton Avenue, I noticed that it looked as old and tired as I felt. And yet its very existence was rare in a city bent on making everything new. I usually met Claudia at the college for lessons, but when she learned that I was a realtor, she invited me over. When I arrived, I learned that she had arranged a sale of her home to a daughter of a friend for 1.8 million and all I needed to do to earn my $50,000 commission was draw up the paperwork and show up at the closing.

As I was leaving, she handed me a piece of sheet music, the first movement of Beethoven���s ���Moonlight Sonata.��� She silently closed the door as I puzzled over the complex notation. How would I ever begin to play this? But my heart was flipping over this sale. I couldn���t wait to tell Lena.

There was no one at home. Lena had left a note on the kitchen counter: ���Kids spending the night out. Fridge bare. Carrie and Gray coming at 7. Picking up steaks.��� I sat down at the piano with the sonata. A note fluttered down from the pages. It was written in Claudia���s scrawl:

���We are born knowing everything and spend the rest of our lives remembering what it is we already know.���

I put the note on top of the piano. Claudia often wrote cryptic notes in my music for me to puzzle over later or discuss. I moved my hands over the keys, but it would take me months to learn just the basics of the piece. And yet Claudia���s note reassured me that I had to trust my body and my fingers to follow through and eventually learn the correct movement as I played it again and again. I had heard and seen my brother learn challenging pieces, and though he was a quicker study, what had mattered, it seemed, was a trust that any piece could be mastered. Claudia���s encouragement was to trust a native instinct, something we are born with, but have forgotten because of doubt and fear.

I called the kids where I guessed they might be staying for the night, and they treated me like some sad sack they had to reassure before they could get back to the popcorn and movies and video games or whatever it was they were doing. Our presence together on the nights when Lena worked late was essential to me, somehow, and without them, I felt vulnerable, like a wild animal without its pack. It assured me to hear their voices on the phone, even to hear their exasperation with me.

After picking out a few notes of Beethoven���s famous ���Moonlight,��� I broke down and opened a bottle of wine, lit candles and turned on the local jazz station. Lena would be home any minute and I knew what it took to get my wife in bed and I was fooling myself with Beethoven and quiet songs. I drank a couple of glasses of wine. I had been too soft, too forgiving. I had earned half a year���s salary in one day, goddamnit.

���Welcome home,��� I said when she walked through the back door. I took the grocery bag and put it in the refrigerator. I handed her a glass of Cabernet. She was wearing her cream blouse printed with gold rings and horses, a classic blouse she wore with pearls and a navy wool skirt. She knew how to dress for the judge and the jury, was an expert in personas and angles and argumentations. I kissed her mouth. Her lipstick tasted like cake.

���What���s all this?��� she said. The candles and the jazz playing on the sound system were unusual occurrences.

���Fifty thousand dollars,��� I said. The power of this truth made my mouth water. I wanted to rip the silk shirt off of her. I wanted to scatter the pearls to the far corners of the kitchen.

���Wow!��� she said, giving me a quick enthusiastic hug around the neck. ���That���s wonderful.��� She took a sip of wine. She watched me with her green eyes..

���It was a 1.8 million dollar sale.��� I took the glass from her and drew her into an embrace. I kissed her.

She pushed off from my chest and touched her lips to mine with an emphatic peck.

���I want to take a bath,��� she said.

I nuzzled her hair.

���Could you run a vacuum?��� she said.

She twisted in my arms. I let her go.

I turned my back to her and opened the cabinet for a glass. I poured a scotch. She grabbed the bottle of wine and climbed the stairs, her feet padding on the carpet. I heard the pipes click with the rush of water into the tub.

I should have gone upstairs. I should have taken what was mine. I should have wreaked havoc at the first suggestion of a ���vacuum.��� The urge to empty the contents of the vacuum cleaner bag onto Gray���s usual chair shot through me, but then Gray and Carrie were at the door as I was suctioning up debris in the hall.

���Isn���t this a sweet picture,��� said Gray. ���An enlightened male. You���re making me look bad, man.���

���I think you���re doing just fine on your own.���

���All right, you prick, where���s the liquor?���

���It���s a full moon tonight,��� I said. ���The jackal���s here.���

���Cut it out, Richard!��� said Lena, shouting down from the top of the stairs. She had bathed quickly. ���Help yourself to the drinks everybody, I���ll be down in a minute.��� Gray went to the basket on the countertop where we kept a jumble of liquor choices.

Lena came down and kissed everyone.

���Well,��� I said. ���Now that I���ve done my duty for a bit, I���m going to sit down to the piano.��� I raised my Scotch to everyone as I backed out through the door.

���A toast, everybody,��� said Lena. ���My husband just made a $1.8 million sale.���

As I left the room, I heard her explaining my windfall. I wanted to kiss her. I wanted to embrace her. But as I walked away, I knew she was being my public Lena. She

was loving me with the only resources she had left, with a cushion of people between us and no expectation of sex, just my appreciation and adoration.

I opened an intermediate piano book and began playing one of the pieces I knew well. I would play until I was calm. I would play until I couldn���t hear Gray yammering. We often cooked out when they came over, so I knew it was only a matter of time before

Lena and Gray went outside with their drinks to preheat the grill. In the meantime, I would build a wall of notes between myself and the things I didn���t want to confront.

I heard Carrie slip through the doorway off the hall and sit in her seat. Lena shouted out that she and Gray would be sitting on the back porch. It was quiet now in the house, except for the piano. The sun had gone down and the light over the music reflected brightly off the paper. I imagined Carrie in the gray light behind me. I played almost every piece I knew.

When I had played myself out, I laid my fingers upon the keys. ���The thing about music, as about anything beautiful or grand,��� said Claudia to me once, ���is that it must end.���

As I sat there, hunched over on the seat, I smelled air from outside. Gray and Lena must have left the door open. It was difficult for me to move. The furniture sat about me like stones. Something, I felt, had shifted. Something had changed in the atmosphere. I sensed it was the kind of change that occurs after an act of violence or a cataclysmic natural event. There was no escaping it, this discovery of whatever it was.

���Does it seem quiet to you?��� I said to the darkness, to Carrie, unable to think of anything else to say.

I heard her rise from her seat and come up beside me. I felt her hand, light as a girl���s, on my shoulder.

I stood and turned to face her.

She kept her place beside the piano, her face illuminated by the piano light. ���I have been coming to see you for a very long time.���

I was silent.

���Do you feel something for me?���

I picked up her hand. It was small and delicate in mine, like a small bird. I caressed it and held it to my mouth. I held it against my cheek but said nothing.

She yanked her hand away. Tears streamed down her cheeks and she swiped at them.

She turned and left for the kitchen and I followed, wanting to hold her to reassure her. I had missed something, some small moment. The spaghetti strap on her freckled shoulder was so delicate, but she was through the back door and onto the porch before I could make up my mind to touch her.

There was a large moon in the sky. The steaks lay cold and hardened in their fat on the China plate near the grill. On the silvered lawn, there was no sign of Gray or Lena. Shadows from the oak cast illusive shapes. The oleander at the boundaries of the yard danced, their flowers nodding. An overripe globe fell from the orange tree. A gasp cut through the wind, and then a tiny cry, private and raw. Gray���s body was pressed against my wife. They were standing against the oak, on the far side of the trunk. I could see them now, their bodies separating from what had once appeared to be one dark mass.

I stepped out into my yard. I sprinted to the tree and yanked Gray from my wife. He stumbled and fell while Lena collapsed as if she had a cramp. Carrie ran up behind me and grabbed my arm and I threw her off. She fell to the ground. I stood, watching Gray struggle to rise, but I couldn���t leave Carrie there on the grass.

���Shit,��� said Gray. ���Give it a rest.��� He pulled up his pants which had been at his ankles. He rubbed his fist against his lip. He told Carrie to go to the car. Lena wrapped

her mussed up clothes around her. She scurried inside. Gray walked through my house. I followed. He sat on the steps of my front porch and tied his shoes. I wanted to rip his hair out at the root. I wanted to smash his forehead against the porch railing.

���Now let���s just check facts,��� he said. ���Carrie comes to your house ��� your house – for no apparent reason other than to listen to you play scales and tinker with a few little pieces on your piano. OK, now, if I had any other wife, I might have deep, deep suspicions. But Carrie, oh please,��� he snorted. ���So I have no reason to worry, you know?

“But the thing about it is, Bach, that two weeks ago, I had to leave work and pick up one of our kids from school and take him to the ER. You see, that���s because he broke his arm on the playground and no one could find my wife. That���s because she was with you. So you see what my problem is? Do you see why I can���t have this? You blow my mind, you fucking weirdo. What the hell is wrong with you?���

He stood and walked down the steps towards his car, towards Carrie.

I pushed his shoulder so that he tripped down onto the sidewalk. He raised his hands as if in surrender.

After the Porsche had roared away, I turned off the lights and climbed the stairs. In the bedroom, Lena lay facing the window. She was too still to be asleep.

���I heard you,��� she said. ���You and Gray.��� She rolled over and sat up. Strands of hair were matted to her face.

I opened the chest of drawers and pulled out a t-shirt.

���You know, now would be a good time to say something,��� she said.

I couldn���t breathe.

���Just so you know,��� she said, ���Since you apparently aren���t going to ask, we did it because we had been drinking and I felt like it and I had forgotten all about you. We didn���t even think you���d be coming out. You and Carrie.���

As I dressed, I felt a stiffness in my body, but I would not look at her, would not acknowledge her.

���Gray told me she���s been coming over to listen to you play piano. He says she���s not capable of an affair. I���m sure you wish I were more like her, more, let���s see, what���s the right word, simpler, more self-effacing. But you know what, it doesn���t matter. Hell, I

don���t even give a shit anymore. I don���t even want you. I haven���t wanted you for a long time.���

She flung herself back on the bed and pulled up the covers. I slammed the door shut and the window rattled down the hall. I slept in my son���s room. I thanked God he and his sister were away for the night. I had a thought that perhaps every parent has at least once, but that I���ve had many times recently – that our children would have been better served by others. I continued to have this thought as Lena moved out and we began divorce proceedings and custody battles.

A few weeks before my divorce was final, I mastered that piece by Beethoven, his

first movement of ���Moonlight.���

January 26, 2015

woman in the wood (the kingdom of bluebeard)

I stopped to collect myself��among the poplars, I stopped to find peace within for the journey, for a self divided and frightened was no defense against the spirits seeking empty places, holes within��a soul��riven with anxiety. The woman of the stick house said in our country, newly blackened by evil, I would encounter��spirits��of all forms, life forms animated by hungry senas who would seek to impair me on my journey for I had something they lacked: breath.

Among the fresh sprinkling of snow I spied a woman, unclothed and beautiful. She was crying, wailing out for her lover. “Who are you?” I asked her, approaching, thinking I was protected by the amulet and blessing given me by the woman of the stick house. “How is it that you are unclothed? Why are you here?”

“My bridegroom, my husband, he was displeased.”

“And so you are in the snow, naked, unclothed and alone? There are wolves.”

“I did not please him. He put me outside.”

“Yet you are beautiful.”

And as soon as these words left my lips, other women drifted from the trees as if they were the trees or a part of their smooth white bark. All of them were crying, and yet I found their sound not harsh or unpleasant, just a sound like bells ringing at once on a clear cold winter, each had their own tone but were in harmony with each other.

“We have all displeased him,” they said together, with one voice. “He touched us, he took what he wanted, and now we are without love or prospects.”

Women of flesh would not be able to survive such conditions. I��made to steel��myself from them lest I be overcome with pity. They should be redeemed but now would not be the time. If I allowed it, they would undo me with weeping and take away the courage I must have to escape to escape to higher country.

They surrounded me.

“Can we not drink from your amulet?”

They were not unlike my mothers and sisters and had been trusting once, and yet they had not learned to be wise. A soul that has acted against its own behalf has the force of anger doubled back. The feet of these women burned through the ground as they walked, as they approached they grimaced and their teeth appeared as the��coyotes which roamed the upper region.

“I respect your plight, but I should be on my way,” I said, careful not to let on that I saw the whole of their bodies burning through the earth and the true nature of what lay behind their beauty – the pain, anguish, and wildness of grief. That they should be loosed upon the land by the same man whose reign would remain unchecked unless another man sought to oppose him stole my heart but I could not stop. Instead I built a fire in the middle of the woods. I loaded a pile of dry wood quickly before the snow settled in and began a spark with my flint.

I could feel their hands on my back, my hair, my face, as I attempted to make something good for them, to help in some way. They were irrepressible in their need and yet I understood them just as much as they frightened me.

“I am you,” I said. “When one of us is free, it will be the as if it has happened for each of us. You must let me go now so we may return to the goodness that we knew in the kingdom before this darkness fell. Keep this light going as a promise. I want to look wherever I am and see evidence you are here, keeping alive the hope that all will not be as it is now.”

They did not let me go, so deep was their hunger, but I managed to be away using as a torch a burning branch, senas instinctively recoiling from flame though it would do nothing, in actuality, to harm their ethereal forms.

Meg Sefton's Blog

- Meg Sefton's profile

- 17 followers