Andre Bagoo's Blog, page 4

May 6, 2018

On James Thomson’s ‘The City of Dreadful Night’

But which city? London? Or Port of Spain? It would not have mattered to James Thomson. Nor should it matter to us.

Thomson’s poem, which first appeared in 1874, is concerned with the streets we all walk. This is not the ‘Dark Night of the Soul’ of St John of the Cross, where rapture and pain couple. Nor is it the fighting rhetoric of the ‘Terrible Sonnets’ of Gerald Manley Hopkins. Nor do we get any of the embers of Ovid’s curse poems from exile. Thomson also wrote satire, and it would be tempting to regard his poem as something of a parody, yet it does not even have the wicked energy required. It is a pallid, stony edifice where the narrator’s highest hope is to find fellow sufferers. They are the audience he envisions: “no secret can be told / To any who divined it not before”.

Yet, this is the poem I have lighted upon. I want to ask: is it possible to read a poem for the spaces between its language, its ideas? Is this not how we read all poems? And, therefore, should we not judge a poem by what it aims to do? By the world it creates, the function it fulfills? Style is an important thing, but it is just as subjective as an approach that sees the value of a poem in its penumbra.

Thomson suffered from alcoholism, insomnia, and depression. It is not hard to find the sources of his cyclical anguish: he was orphaned as a child, his younger sister died when he was five, then his first love in 1853. Early trauma stays with us, is prolonged and revived by later events. This poet’s language reveals him entirely: he seeks to build a solid world and ends up with a phantasmagoric sequence in which his loved ones irrupt the sprawling narrative and are, thereby, resurrected and memorialized. Reading the poem thus, who is not moved by ‘The City of Dreadful Night’? It is not a poem engendered by a place, but a place engendered by a poem. It is a dramatization of the power of language to make something real.

It is fitting these words are now translated into images. For in the end, what is the difference? Concrete poetry, visual poetry reminds us that writing and text are performers, acrobats, and archives all in one. Words are images: on the page and as concepts in the mind. And the body, too, is a word on the page, an image fashioned by our minds and all that we devise to clothe it. At the time of writing, a reckoning was happening in Trinidad and Tobago.

Colonial laws banning anal sex and criminalizing various forms of gay intimacy were being challenged in court. Members of the LGBTQ community staged protests in front of the Trinidad and Tobago Parliament that had – decades after Independence from Great Britain – preserved the laws. The same Parliament had also added a few variations of its own: banning the entry of homosexuals from the country (Immigration Act); removing gay people from the protections of anti-discrimination law (Equal Opportunity Act); leaving gaps in the law effectively allowing hate-crimes under the guise of “provocation” (Offences Against the Person Act).

Members of various religious sects decided to march to urge the State to preserve the buggery law. In response, members of the LGBTQ community took to the streets. I took a break from writing this book to participate in protests. In the end, the court ruled the buggery law unconstitutional, but other provisions entrenching discrimination still remain. Justice Devindra Rampersad was celebrated by some, but others greeted his ruling with renewed bigotry, violence and intimidation.

The prevailing sense of dread, the fear of walking the streets, the feeling which only members of the LGBTQ community here know and endure daily—that is the same current that flows in Thomson’s poem, now translated here into visual expressions that mirror the moods and spaces between his gothic words. This is a city that could be in any country: a space where bodies are suspended by text outlawing love.

Andre Bagoo

Port of Spain

23 April, 2018

May 2, 2018

From Saturday’s rehearsal for Thursday’s PITCH LAKE reading. Xo

From Saturday’s rehearsal for Thursday’s PITCH LAKE reading. Xo

April 26, 2018

THE CITY OF DREADFUL NIGHT, my book-length visual poem sequence,...

THE CITY OF DREADFUL NIGHT, my book-length visual poem sequence, will be published by Prote(s)xt — an imprint of Hesterglock, UK, in 2018.

April 1, 2018

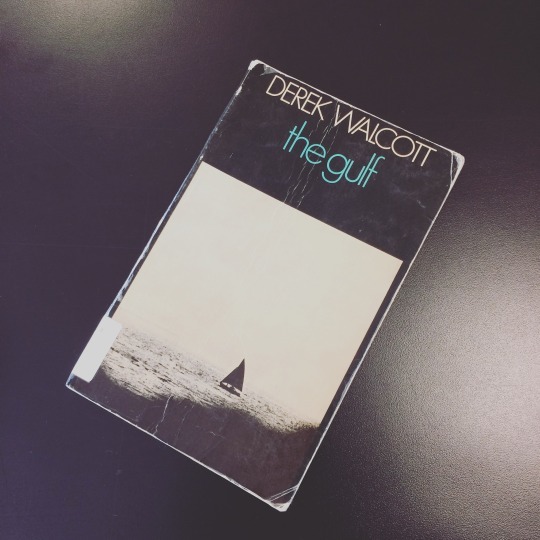

Turning the page — essay on Derek Walcott at Black Renaissance Noire, Vol 17, Issue 2

SOMETIMES a poem haunts us. Try as we might to resist, it lingers. We may not understand its hold on us. Like a wrestler caught in a surprise grip we are rendered momentarily dumb, astonished by our helplessness. Only gradually do we return to the surface of things. For some people, the Derek Walcott poem they will remember most is ‘Love After Love’ from 1976’s Sea Grapes. But for me there is something about the final, untitled poem of 2010’s White Egrets. The poem first appeared in 2007 in The New York Review of Books under the heading, ‘This Page Is A Cloud’. It is a poem Walcott built up to over the course of a lifetime. What is so special about it? Let’s read it:

This page is a cloud between whose fraying edges

a headland with mountains appears brokenly

then is hidden again until what emerges

from the now cloudless blue is the grooved sea

and the whole self-naming island, its ochre verges,

its shadow-plunged valleys and a coiled road

threading the fishing villages, the white, silent surges

of combers along the coast, where a line of gulls has arrowed

into the widening harbour of a town with no noise,

its streets growing closer like print you can now read,

two cruise ships, schooners, a tug, ancestral canoes,

as a cloud slowly covers the page and it goes

white again and the book comes to a close.

Just as Schopenhauer asks us to imagine the world being generated by an idea, Walcott requires us to commit to thoughts becoming real in our hands. We look at the page, consider the block of text. We are given a bird’s eye view of the terrain, inhabiting the perspective of the titular white egrets of the book. It all unfurls: the colors of the land, the shapes of valleys, the curves of roads, the serenity of fishing villages. This is a dreamscape. The poet simultaneously casts and breaks his spell: we succumb to the world of the poem, its lines and language but then the suspension of disbelief is broken. Suddenly there is a book in our hands. Poetry has seemingly engendered an object, the same object that provides its genesis. This is a return to the source of all poetry: to the idea as the poet as a maker of things.

What is also telling about the poem is how it alludes to the great concerns of Walcott’s oeuvre without explicitly stating them: history, nature, love. This is not just a picaresque tour. Nor is it a quaint descriptive list. Each item is a symbol, alluding equally to myth as well as social context. The fishing villages are the settings for ancient odysseys and for the industrial-colonial processes that shaped the Caribbean’s history.

And here, what is at first beautiful becomes dangerous. There are shadows stalking the land, the road coils like a snake. “A line of gulls has arrowed” suggesting an offensive, the idea of birds turning on man, as well as the arrows of the Amerindians fighting for survival. Time itself is pierced. Each turn (“a widening harbour”, “a town with no noise”, “streets growing closer”) is a stop along the way in a journey that is both linear and also metaphorical. When “ancestral canoes” appear it is as though an Egyptian burial ship has been excavated. We have crossed over. By the time we arrive at the closing lines (“a cloud slowly covers the page and it goes / white again and the book comes to a close”) we have been on a disorienting journey, traveling film-reel style through a country, through feelings (“white, silent surges”), through life and through ages. That the poem makes us think of the poetry book in our hands is not tangential to the theme of death. For the poet is asking us to reflect on the place of objects in our lives and the relevance of objects in the afterlife.

Throughout his long career, Walcott was coming closer and closer to the ideas he expresses here. In ‘Codicil’, published in 1965’s The Castaway, he writes of a, “clouding, unclouding sickle moon / whitening this beach again like a blank page”. The opening of 1973’s autobiographical Another Life gives us:

Verandas, where the page of the sea

are a book left open by an absent master

in the middle of another life—

I begin here again,

begin until this ocean’s

a shut book…

Then in 1979’s The Star-Apple Kingdom he gives us ‘The Sea Is History’ where, “the ocean kept turning blank pages”. The page is a metaphorical domain for landscape. But in 1987’s ‘To Norline’ a relationship ends and, “when some line on a page / is loved…it’s hard to turn.” The stakes have been raised: the object in our hands is made into part of the poem, not just an idea within it. By 1997’s The Bounty, “cloud-pages close in amen” in response to a bequest.

I don’t think it insignificant that Walcott ends White Egrets with this poem. Throughout the collection he surmises that it will be his last book. He may have at one stage envisioned this poem as his last published poem. When his collected poems, The Poetry of Derek Walcott 1948 – 2013, was published in 2014, this poem brought down the curtain. (The exhilarating lagniappe of Morning, Paramin was yet to come.) By ending with this untitled poem, Walcott implicates us. Like a philosopher concerned with the relationship between ideas, language and reality, he uses the fraught process of reading to ask us to consider what is more real: language or what it describes? Life or death? His words, or the book that has been placed in our hands? When we close that book, what has happened to the poet and his words? And what has happened to us? Do we see the world around us afresh, as if born again? Somehow, whenever I read this poem I never leave it. I always ask more of it. I cannot turn the page.

- first published at Black Renaissance Noire, Vol 17, Issue 2

March 28, 2018

Three Pitch Lake poems — ‘Walt Whitman in Trinidad...

Three Pitch Lake poems — ‘Walt Whitman in Trinidad I’, 'Walt Whitman in Trinidad II’ and 'After Alfred Mendes, Pitch Lake, 1934’ — are featured in the latest issue of NYU Black Renaissance Noire, published by the Institute of African American Affairs at New York University and edited by Quincy Troupe. The poems can be read here.

March 25, 2018

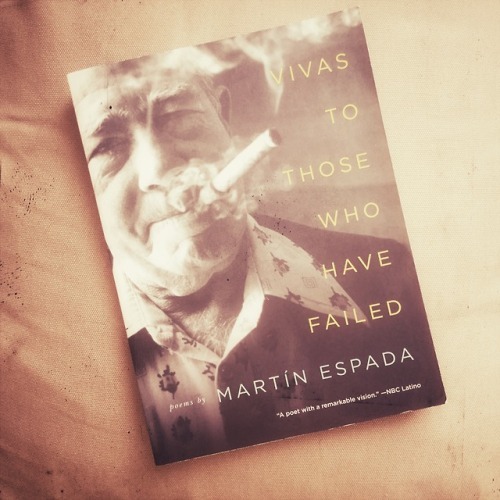

What is failure? Who gets to define “those who have failed”? If...

What is failure? Who gets to define “those who have failed”?

If there is one arena in which notions of failure and success sit uneasily, it is within art. How do we judge the success of a work of literature? By the extent of its readership? By its critical reception? By the author’s personal judgement? And at what stage are we ready to carry out these assessments? On publication? Or a decade after? A century?

- on art, activism and fathers: my review of poet Martin Espada’s latest book, which is dedicated to his father, published at sx salon http://smallaxe.net/sxsalon/reviews/his-fathers-disciple

Great evening with the John Ashberry Bookclub!

#books #bookswag...

Great evening with the John Ashberry Bookclub!

#books #bookswag #bookslut #bookshelf #bookselfie #bookstagram #bookslover #books

Another night reading poetry in London! Great fun unveiling ‘The...

Another night reading poetry in London! Great fun unveiling ‘The Scarlet Ibis’ at SJ Fowler’s #PoemBrut III, a rich and powerful event, thread with serendipitous synergies. Xo (at Rich Mix London)

So that happened! My first reading outside Trinidad and Tobago...

So that happened! My first reading outside Trinidad and Tobago soil was in London at last night’s Shearsman Books event alongside Laurie Duggan and Carol Watts. Thank you Tony Frazer for having me! (Photo: Ludo Smolski) (at Swedenborg House)

March 8, 2018

Readings in March - London

* Tuesday 13 March 2018, 7:30pm: Shearsman Books reading, alongside Laurie Duggan and Carol Watts

Swedenborg Hall, 20/21 Bloomsbury Way, London WC1A 2TH

* Saturday 17 March 2018, 7.30pm: Poem Brut at Rich Mix II 35-47 Bethnal Green Rd, London E1 6LA. With SJ Fowler, Chrissy Williams, Lavinia Singer, Matvei Yankelevich, Julia Rose Lewis, Julia Schuster, Olga Moskvina, Oliver Mayeux, Mischa Foster Poole, Ruhi Parmar Amin and more!