Jade Varden's Blog, page 30

July 23, 2014

Self-Published Books: Getter Bigger Than the Big 5?

Data from AuthorEarnings.com shows that self-published book titles make up 31 percent of Amazon Kindle's book sales, and that's a lot. In fact, it suggests that indie authors are growing as powerful as the Big 5. This is the moniker given to the country's 5 biggest publishing companies, the old guard who for so long dictated popular literature in the United States. Those days might be over.

Mr. Big Stuff

The "Big 5" publishing companies can lay claim to just 38 percent of Kindle book sales. Not only are self-published books taking up a piece of the market that's almost as big, self-published authors get bigger royalties than their traditionally-published counterparts. According to AuthorEarnings, self-published authors earn almost 40 percent of all ebook royalties paid out by Amazon.

If the numbers continue to rise, self-publishing could become the dominant force in the book industry. Wouldn't that be a big change?

Mr. Big Stuff

The "Big 5" publishing companies can lay claim to just 38 percent of Kindle book sales. Not only are self-published books taking up a piece of the market that's almost as big, self-published authors get bigger royalties than their traditionally-published counterparts. According to AuthorEarnings, self-published authors earn almost 40 percent of all ebook royalties paid out by Amazon.

If the numbers continue to rise, self-publishing could become the dominant force in the book industry. Wouldn't that be a big change?

Published on July 23, 2014 11:30

Writing 101: Using Incorrect Grammar on Purpose

All books should be perfectly polished, well-edited, presentable in every way. But there are times when authors might be using incorrect grammar...on purpose. When is it not only okay to break the rules of language, but necessary?

When Bad Writing is Good

Sometimes, bad writing is needed in order to bring the setting to life. Ever read Gone With the Wind? Mammy's voice is clear and strong throughout the novel, and Margaret Mitchell does it with a lot of misspellings and incorrect grammar.

Many authors use incorrect grammar in dialogue and in stories with first-person narrators, and there's a really good reason for it: that's the way people talk. It's correct to say I don't know to where I'm going, but I sound like somebody who walked out of the 1900s when I say that. It's more natural to say I don't know where I'm going to, but this sentence breaks a classic grammar rule. So when is it okay to break the rules, and when should you actively be trying to break them? When you're the way that people actually talk. Real people break grammar rules every single day, and if you don't believe me go look at Facebook for 40 seconds. I promise you'll find problems.

You should strive to write with correct grammar in beautiful English, of course you should. But it's even more important that you actually write the way people talk. Make your dialogue sound real. Make your narrator's voice feel real. Write the way people speak, and try to ignore the grammar rules you break along the way.

Save your beautiful, perfectly-crafted prose for third-person books, the Author's Note and anything else you're going to write in your own voice. When you're writing for characters, make sure you're writing for them. Write the way that character talks; hear them talking to you. Write that way, and your book will feel more real to your readers. It'll be even more beautiful than thousands of perfectly-edited and grammatically precise sentences.

When Bad Writing is Good

Sometimes, bad writing is needed in order to bring the setting to life. Ever read Gone With the Wind? Mammy's voice is clear and strong throughout the novel, and Margaret Mitchell does it with a lot of misspellings and incorrect grammar.

Many authors use incorrect grammar in dialogue and in stories with first-person narrators, and there's a really good reason for it: that's the way people talk. It's correct to say I don't know to where I'm going, but I sound like somebody who walked out of the 1900s when I say that. It's more natural to say I don't know where I'm going to, but this sentence breaks a classic grammar rule. So when is it okay to break the rules, and when should you actively be trying to break them? When you're the way that people actually talk. Real people break grammar rules every single day, and if you don't believe me go look at Facebook for 40 seconds. I promise you'll find problems.

You should strive to write with correct grammar in beautiful English, of course you should. But it's even more important that you actually write the way people talk. Make your dialogue sound real. Make your narrator's voice feel real. Write the way people speak, and try to ignore the grammar rules you break along the way.

Save your beautiful, perfectly-crafted prose for third-person books, the Author's Note and anything else you're going to write in your own voice. When you're writing for characters, make sure you're writing for them. Write the way that character talks; hear them talking to you. Write that way, and your book will feel more real to your readers. It'll be even more beautiful than thousands of perfectly-edited and grammatically precise sentences.

Published on July 23, 2014 05:30

July 22, 2014

Writing 101: And Then...

There are a whole lot of rules in the English language, and we know this to be true because I write about these rules all the time. And as an author, it's part of my job to follow those rules -- strictly. I must cling to them so passionately, in fact, that I actively and aggressively try to get other people to follow those rules. So it may come as a surprise to some blog readers that there's one rule I break...no matter how many times the automatic grammar checker tells me to fix it. Because when it comes to the phrase "and then," I just don't use it. Nope...not at all.

Born to Be Bad

Microsoft is totally against the way I write. My word processor completely believes that the word "then" cannot be used unless its buddy "and" is also involved. I'll give you some examples of sentences that are sure to be flagged:

She reached across the table, then grabbed my hand in a show of support.

He lifted his hand as if to touch me, then let it fall back down to his side.

Those sentences, you see, are grammatically incorrect. When used in this way, then is a conjunction but it's not a stand-alone conjunction. But stands on its own; then does not. Conjunctions always link a sentence with two or more separate clauses; it links two different thoughts, feelings or actions. Shelly moved on the couch, and then she got the the remote from the side table.

Seriously, though, some rules are made to be broken. I happen to think sentences read just fine even when I break this one. I know it's grammatically incorrect, and I do it in my books anyway. I've never had a reviewer, ever, bring it up.

There are other ways to use then without his pal and, however. In fact, I can alter our previous examples to make them correct and I won't use and anywhere.

She reached across the table. Then, she grabbed my hand in a show of support.She reached across the table; she then grabbed my hand in a show of support. He lifted his hand as if to touch me. Then, he let it fall back down to his side.

Or, you could always just add the and.

She reached across the table, and then grabbed my hand in a show of support.

He lifted his hand as if to touch me, and then let it fall back down to his side.

I do none of this, because I think the sentence flows fine without it. I don't break many grammar rules and I don't advocate breaking the rules of language, but over time language is updated. It evolves and changes, and we know this is true because none of us say thou in our daily speech. So if you like the way something sounds and it's true to your voice, maybe it's okay for you to break some of the rules, too.

Born to Be Bad

Microsoft is totally against the way I write. My word processor completely believes that the word "then" cannot be used unless its buddy "and" is also involved. I'll give you some examples of sentences that are sure to be flagged:

She reached across the table, then grabbed my hand in a show of support.

He lifted his hand as if to touch me, then let it fall back down to his side.

Those sentences, you see, are grammatically incorrect. When used in this way, then is a conjunction but it's not a stand-alone conjunction. But stands on its own; then does not. Conjunctions always link a sentence with two or more separate clauses; it links two different thoughts, feelings or actions. Shelly moved on the couch, and then she got the the remote from the side table.

Seriously, though, some rules are made to be broken. I happen to think sentences read just fine even when I break this one. I know it's grammatically incorrect, and I do it in my books anyway. I've never had a reviewer, ever, bring it up.

There are other ways to use then without his pal and, however. In fact, I can alter our previous examples to make them correct and I won't use and anywhere.

She reached across the table. Then, she grabbed my hand in a show of support.She reached across the table; she then grabbed my hand in a show of support. He lifted his hand as if to touch me. Then, he let it fall back down to his side.

Or, you could always just add the and.

She reached across the table, and then grabbed my hand in a show of support.

He lifted his hand as if to touch me, and then let it fall back down to his side.

I do none of this, because I think the sentence flows fine without it. I don't break many grammar rules and I don't advocate breaking the rules of language, but over time language is updated. It evolves and changes, and we know this is true because none of us say thou in our daily speech. So if you like the way something sounds and it's true to your voice, maybe it's okay for you to break some of the rules, too.

Published on July 22, 2014 05:30

July 21, 2014

Writing 101: Guilds, Groups and Other People

As an author, you need support. You need honest feedback. You may even need help figuring out certain writing techniques and double-checking your ideas. It's attractive to start joining guilds and groups, and plenty of writers advocate that. But when you mix with other people, you're always going to wind up with a mixed bag. Joining groups and getting involved has a good side...but plenty of writers will tell you about that. I'm going to flip the coin, and talk about the dark side of sharing your writing with other people before you've finished with it.

Team Players

I have often mentioned my childhood fantasy of being a writer. I would be sitting in a quiet room -- maybe in an attic, somewhere, or some book-lined room -- all alone just typing away. That, to me, is truly living the dream. Why? Because writing is solitary. You do it alone. To me, the idea of joining up with other writers has always seemed...damned counter-productive, to put it mildly.

But even I can see the merits in it. Writer groups can be helpful if you've got questions or want to test your ideas. Joining a group can help you find beta readers and review buddies and, I guess, lifelong friends.

When it all goes perfectly, of course. But when you're on the Internet and you're dealing with other writers and they're creative types who may be just hovering on the brink of a total exhaustive breakdown because they've been typing for three days straight...well, things can get ugly pretty quickly. And this isn't even the worst of the reasons why you may want to stay away from guilds, groups and other people when it comes to your writing ideas, questions and heartache.

Creativity: If you start bouncing your ideas off random people online to see what they think, you're stifling your own creativity. Why would you do that? You owe it to yourself to see how your own ideas work out, and try writing them down, before you seek the approval of others. If I told you I'm writing a story about a midget who goes on a long hike you might say it sounds boring, but Lord of the Rings is based on this very premise. Dues: Thinking of joining a writing guild or group? Read all the fine print. Some groups, and guilds in particular, may require you to pay dues or perform some other task to maintain your membership. It's not always a great idea to pick up a bunch of commitments. Remember, you need time to write and your money is probably pretty precious.Devotion: Speaking of time, when are you going to use it to write? Popular writing groups and forums stay pretty darn active, and you can drive yourself crazy trying to keep up and maintain a normal life, too. I know, because I've done it.And Then There's Google: If you've got writing questions, you can always find the answer on your own with no one's help. As an author of books, you need to know how to research -- and you need to know how to research anything. Start by answering your own questions. If you've got to get help from others when it comes to writing, Heaven help you when you need to know about the migratory habits of birds during fall in Vermont. Don't tell me you won't need to know that -- you'd be surprised what crops up when you're crafting a novel.

Guilds, groups and other people certainly have their uses. But sharing early ideas with them, asking a bunch of questions of them and wasting your time in arguments with them are not among those uses. It can be a huge distraction and keep you from doing what you need to do. Learn how to use them well, avoid all the junk, and maybe you can get something out of your efforts.

Team Players

I have often mentioned my childhood fantasy of being a writer. I would be sitting in a quiet room -- maybe in an attic, somewhere, or some book-lined room -- all alone just typing away. That, to me, is truly living the dream. Why? Because writing is solitary. You do it alone. To me, the idea of joining up with other writers has always seemed...damned counter-productive, to put it mildly.

But even I can see the merits in it. Writer groups can be helpful if you've got questions or want to test your ideas. Joining a group can help you find beta readers and review buddies and, I guess, lifelong friends.

When it all goes perfectly, of course. But when you're on the Internet and you're dealing with other writers and they're creative types who may be just hovering on the brink of a total exhaustive breakdown because they've been typing for three days straight...well, things can get ugly pretty quickly. And this isn't even the worst of the reasons why you may want to stay away from guilds, groups and other people when it comes to your writing ideas, questions and heartache.

Creativity: If you start bouncing your ideas off random people online to see what they think, you're stifling your own creativity. Why would you do that? You owe it to yourself to see how your own ideas work out, and try writing them down, before you seek the approval of others. If I told you I'm writing a story about a midget who goes on a long hike you might say it sounds boring, but Lord of the Rings is based on this very premise. Dues: Thinking of joining a writing guild or group? Read all the fine print. Some groups, and guilds in particular, may require you to pay dues or perform some other task to maintain your membership. It's not always a great idea to pick up a bunch of commitments. Remember, you need time to write and your money is probably pretty precious.Devotion: Speaking of time, when are you going to use it to write? Popular writing groups and forums stay pretty darn active, and you can drive yourself crazy trying to keep up and maintain a normal life, too. I know, because I've done it.And Then There's Google: If you've got writing questions, you can always find the answer on your own with no one's help. As an author of books, you need to know how to research -- and you need to know how to research anything. Start by answering your own questions. If you've got to get help from others when it comes to writing, Heaven help you when you need to know about the migratory habits of birds during fall in Vermont. Don't tell me you won't need to know that -- you'd be surprised what crops up when you're crafting a novel.

Guilds, groups and other people certainly have their uses. But sharing early ideas with them, asking a bunch of questions of them and wasting your time in arguments with them are not among those uses. It can be a huge distraction and keep you from doing what you need to do. Learn how to use them well, avoid all the junk, and maybe you can get something out of your efforts.

Published on July 21, 2014 05:30

July 17, 2014

Writing 101: First Draft Questions

Finishing a first draft is an amazing feeling, and I want you to enjoy it...for a little while. But once that moment of joy is good and done, it's time to get down to the real work. Because up until now, you've been having fun. Now you have to edit your work, and that means you have to ask yourself the dreaded first draft questions.

Don't have first draft questions? It's time to get some. Otherwise, how will you make sure your story is air-tight?

That's My Interrogative

First drafts are meant to be a bit frenzied. You've got a outline but you're not always following it, because the story ends up going somewhere you didn't quite expect. You're not sure if pineapples grow in Hawaii but you think so and you're going to check it later so that's fine. You haven't finished that one scene with the green plate because you can't quite figure it out, but you're getting back to that later so who cares.

It's okay to do that in a first draft. You've got to just get the story on the page, and the little details will get filled in later if they're missing.

Well, hello -- and welcome to later. Because while it's good to play the part of the free-spirited artist while you're writing the first draft, you've got to get serious and become the boss as soon as you begin editing the very first page. No more playing it by ear or skipping over it for now. You've got to double-check facts, tighten up that sentence structure and become the drill sergeant of the book. Make Chapter 11 do those push-ups, or else.

But while you're doing all that, make sure you're asking all your essential first draft questions. If you don't, you could end up with plot holes and missing information that will keep your book from being its very best.

There's no one list of questions that will suit every book, because each book has different plots with different settings and characters. Certain questions will only apply to your book. But I've come up with a few general questions you ought to keep in mind the entire time you're re-reading your work.

Does this make sense? Every line, every scene, every chapter has to make sense. This seems so simple, and yet it's so easy to get wrong. Try to refrain from using oblique references or strictly regional phrases, unless you're also explaining these colloquialisms. If you've got a scene where a character picks up fire and hurls it, ask yourself if that makes sense. If we understand that the character has some sort of power then perhaps it does, but if no one knows about the power but you it's unlikely readers will get it. How did we get here? If your characters are on the move, make sure we know it. For example, if you have a scene where your character is in the pool and they're in the bedroom in the very next scene, tell me how they got there. You can take care of that with one line. We always need cohesion, unless you've left a gap to create a specific effect. What happened to so-and-so? Don't forget about the other characters in your books. Supporting cast members can't be at loose ends, either. Unless you're specifically hiding a character for a literary purpose, don't allow your cast members to simply disappear. What does that mean? If you're using an invented language or made-up names of any kind, make sure readers know what all these words mean. Explaining it once may not be enough, because there's a lot of information to absorb in a book. What does it look like? Always paint every scene. If you're asking yourself what this place looks like, readers will be asking the same question. And remember to describe landmarks and well-known places, too. Not everyone knows what a Wal-Mart looks like, and we haven't all visited the Grand Canyon.

Come up with your own first draft questions to make sure your plot is sticking together the right way. Remember that if you've got unanswered questions while you read your book, everyone else who reads it will have them, too.

Don't have first draft questions? It's time to get some. Otherwise, how will you make sure your story is air-tight?

That's My Interrogative

First drafts are meant to be a bit frenzied. You've got a outline but you're not always following it, because the story ends up going somewhere you didn't quite expect. You're not sure if pineapples grow in Hawaii but you think so and you're going to check it later so that's fine. You haven't finished that one scene with the green plate because you can't quite figure it out, but you're getting back to that later so who cares.

It's okay to do that in a first draft. You've got to just get the story on the page, and the little details will get filled in later if they're missing.

Well, hello -- and welcome to later. Because while it's good to play the part of the free-spirited artist while you're writing the first draft, you've got to get serious and become the boss as soon as you begin editing the very first page. No more playing it by ear or skipping over it for now. You've got to double-check facts, tighten up that sentence structure and become the drill sergeant of the book. Make Chapter 11 do those push-ups, or else.

But while you're doing all that, make sure you're asking all your essential first draft questions. If you don't, you could end up with plot holes and missing information that will keep your book from being its very best.

There's no one list of questions that will suit every book, because each book has different plots with different settings and characters. Certain questions will only apply to your book. But I've come up with a few general questions you ought to keep in mind the entire time you're re-reading your work.

Does this make sense? Every line, every scene, every chapter has to make sense. This seems so simple, and yet it's so easy to get wrong. Try to refrain from using oblique references or strictly regional phrases, unless you're also explaining these colloquialisms. If you've got a scene where a character picks up fire and hurls it, ask yourself if that makes sense. If we understand that the character has some sort of power then perhaps it does, but if no one knows about the power but you it's unlikely readers will get it. How did we get here? If your characters are on the move, make sure we know it. For example, if you have a scene where your character is in the pool and they're in the bedroom in the very next scene, tell me how they got there. You can take care of that with one line. We always need cohesion, unless you've left a gap to create a specific effect. What happened to so-and-so? Don't forget about the other characters in your books. Supporting cast members can't be at loose ends, either. Unless you're specifically hiding a character for a literary purpose, don't allow your cast members to simply disappear. What does that mean? If you're using an invented language or made-up names of any kind, make sure readers know what all these words mean. Explaining it once may not be enough, because there's a lot of information to absorb in a book. What does it look like? Always paint every scene. If you're asking yourself what this place looks like, readers will be asking the same question. And remember to describe landmarks and well-known places, too. Not everyone knows what a Wal-Mart looks like, and we haven't all visited the Grand Canyon.

Come up with your own first draft questions to make sure your plot is sticking together the right way. Remember that if you've got unanswered questions while you read your book, everyone else who reads it will have them, too.

Published on July 17, 2014 05:30

July 16, 2014

Writing 101: Roman a Clef, or How to Beat the System

I'm personally fascinated by history, but it's difficult for me to use this passionate love affair in my writing because I'm interested in real history and real historical figures. And if you write about real people in your books, even those who are long dead, you may experience backlash in all sorts of different forms. But other authors have learned how to beat the system, and they've done it so well there's an entire literary technique named for this sort of savvy trickery. It's called roman a clef, and you don't even have to be French to use it to avoid lawsuits and other author troubles.

At Their Own Game

Want to write about something real, but fear reprisal? Don't shrink from the story you want to tell. Pull a fast one on them, and use roman a clef.

This French term is used to describe a novel that is about real life -- real events and real people. This type of novel, however, is very thinly disguised as fiction. The trick is that the names are changed, and a key is added to the back of the book showing which "characters" represent which real people.

It's just that easy to beat the system. And it's been done time and time again by countless authors for all sorts of reasons.

The roman a clef technique can be used to write about controversial subjects, such as politics, without putting the author at risk of lawsuits. Some authors use this technique in order to remove themselves from the story; they don't want to go public with the fact that the main character is actually themselves.

This technique has been in used since at least 1466, and it's still being used today because it works. Some examples of this technique include The Sun Also Rises, by Ernest Hemingway. The book is about Hemingway's own exploits in Paris and Spain, where he rubbed elbows with many famous names of the day. George Orwell's Animal Farm contains several characters who were figures in the Soviet Union. Sylvia Plath's depressing The Bell Jar is about herself. The Devil Wears Prada is possibly about Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour (Meryl Streep's characrer in the film), but the author denies it.

No technique is foolproof, of course, and no author is fully safe when writing about real people. So always use caution, and remember it may be much wiser to continue calling your book fiction and refusing to name any real names. You don't have to stop writing that story, or avoid using the characters you want. Just change the names, hide the truth a little, and play it safe.

At Their Own Game

Want to write about something real, but fear reprisal? Don't shrink from the story you want to tell. Pull a fast one on them, and use roman a clef.

This French term is used to describe a novel that is about real life -- real events and real people. This type of novel, however, is very thinly disguised as fiction. The trick is that the names are changed, and a key is added to the back of the book showing which "characters" represent which real people.

It's just that easy to beat the system. And it's been done time and time again by countless authors for all sorts of reasons.

The roman a clef technique can be used to write about controversial subjects, such as politics, without putting the author at risk of lawsuits. Some authors use this technique in order to remove themselves from the story; they don't want to go public with the fact that the main character is actually themselves.

This technique has been in used since at least 1466, and it's still being used today because it works. Some examples of this technique include The Sun Also Rises, by Ernest Hemingway. The book is about Hemingway's own exploits in Paris and Spain, where he rubbed elbows with many famous names of the day. George Orwell's Animal Farm contains several characters who were figures in the Soviet Union. Sylvia Plath's depressing The Bell Jar is about herself. The Devil Wears Prada is possibly about Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour (Meryl Streep's characrer in the film), but the author denies it.

No technique is foolproof, of course, and no author is fully safe when writing about real people. So always use caution, and remember it may be much wiser to continue calling your book fiction and refusing to name any real names. You don't have to stop writing that story, or avoid using the characters you want. Just change the names, hide the truth a little, and play it safe.

Published on July 16, 2014 05:30

July 15, 2014

Writing 101: How to Run Your Email

Indie authors have to spend a lot time promoting their books. They use forums, they tweet, they blog -- they're out there. And when you're building an online personality and reaching out a lot on the Internet, you're going to get a lot of email. If you don't run it the right way, it will end up running all over you.

I didn't notice how many emails I was really getting, or how often I was actually checking my inbox, until I changed the notification sound on my phone. It's a loud sound, and it's a good one -- until you have to hear it 30 times a day. But it's not the notification's fault; it's mine. And if you don't know how to run your email, you're going to end up like me: with a phone on silent mode, and missing all your calls.

Run This Town

When it comes to running your indie author email, it's not enough to practice the self-discipline that I've preached in the past. It's important not to get distracted by email, but don't make it impossible on yourself. Use some of the tips I've learned to use, and run your inbox. Don't let it run you.

Spam: If something is spam, mark it as spam. All the notifications I get from Wattpad and Pinterest, for example, don't ever bother me because I don't have to see them. I'm the type to mark forum notifications as spam as well, along with plenty of other stuff. But everyone has their own definition of spam. Figure out what you don't need to see, and send it to spam.Prioritizing: Of course, once you mark a sender as spam it all goes to spam. And not all emails from the same sender are created equal. For example, Twitter. It's not useful to me to see emails for every time I get a retweet or a new follower because I check my notifications on site, but some of the stuff Twitter sends through email is helpful. Their lists of suggested accounts to follow, for example, can be useful to indie authors. So instead of blacklisting everyone and sending everything to spam, prioritize it. Gmail automatically organizes mails into three folders: primary, social and promotions. Emails that you want to prioritized can be moved from the social folder to the primary folder. Move your emails a few times, and Gmail will start to prioritize your mails correctly. Don't forget: Like I said, I get a lot of emails. So many that I have to take time to check my inbox throughout the day, or find myself too bogged down with email housekeeping by the time night rolls around. So I check it every time I come to a natural pause in my writing, and that makes it easy to forget about emails that I still need to answer. So when you find an important email that you need to address but you can't deal with it right now, mark it. Many email apps allow you to put a little star next to the mail, so you can visually mark it. But all programs will allow you to mark a message as unread, so you can still get back to it later.

Being an indie author means getting lots of emails. Don't let important messages get lost in the shuffle, and don't let all the extra notifications take over your inbox. Learn how to run it...because otherwise, you'll just get lost.

I didn't notice how many emails I was really getting, or how often I was actually checking my inbox, until I changed the notification sound on my phone. It's a loud sound, and it's a good one -- until you have to hear it 30 times a day. But it's not the notification's fault; it's mine. And if you don't know how to run your email, you're going to end up like me: with a phone on silent mode, and missing all your calls.

Run This Town

When it comes to running your indie author email, it's not enough to practice the self-discipline that I've preached in the past. It's important not to get distracted by email, but don't make it impossible on yourself. Use some of the tips I've learned to use, and run your inbox. Don't let it run you.

Spam: If something is spam, mark it as spam. All the notifications I get from Wattpad and Pinterest, for example, don't ever bother me because I don't have to see them. I'm the type to mark forum notifications as spam as well, along with plenty of other stuff. But everyone has their own definition of spam. Figure out what you don't need to see, and send it to spam.Prioritizing: Of course, once you mark a sender as spam it all goes to spam. And not all emails from the same sender are created equal. For example, Twitter. It's not useful to me to see emails for every time I get a retweet or a new follower because I check my notifications on site, but some of the stuff Twitter sends through email is helpful. Their lists of suggested accounts to follow, for example, can be useful to indie authors. So instead of blacklisting everyone and sending everything to spam, prioritize it. Gmail automatically organizes mails into three folders: primary, social and promotions. Emails that you want to prioritized can be moved from the social folder to the primary folder. Move your emails a few times, and Gmail will start to prioritize your mails correctly. Don't forget: Like I said, I get a lot of emails. So many that I have to take time to check my inbox throughout the day, or find myself too bogged down with email housekeeping by the time night rolls around. So I check it every time I come to a natural pause in my writing, and that makes it easy to forget about emails that I still need to answer. So when you find an important email that you need to address but you can't deal with it right now, mark it. Many email apps allow you to put a little star next to the mail, so you can visually mark it. But all programs will allow you to mark a message as unread, so you can still get back to it later.

Being an indie author means getting lots of emails. Don't let important messages get lost in the shuffle, and don't let all the extra notifications take over your inbox. Learn how to run it...because otherwise, you'll just get lost.

Published on July 15, 2014 05:30

July 14, 2014

Writing 101: What's Your Hook?

Like the best hit songs, good books need to have a great hook. There are all sorts of different ways to hook readers right at the beginning of a story. Do you know how to use all of them?

Baiting the Hook

How a story begins is really the most important thing about it, because there are readers out there who will look at this and nothing else. If you don't catch those readers who nibble on those first few lines, and get them reeled in, you'll lose them for ever. There are many different literary devices which can be used to hook readers. Get to know them, learn how to use them and then figure out how to make them your own.

Flashback: Go into the distant past to hook readers with a flashback scene. Show what life was like before the stuff that happens in the story, and make it look really amazing. This works well when the book will be showing events that are totally different.Flashforward: Look back at the events of the book with some perspective, dropping tantalizing hints about how the things that happened affected the world, the characters or whatever. This is a common narrative plot device, but a good writer can still make this an exciting technique. Story-within-a-story: It's always interesting to begin a book as a story that's being told to someone else. An example of this occurs in Arabian Nights, in which the storyteller is using short stories to stave off execution. In media res: This sounds like a very fancy technique, but it's really one of the most commonly used. In media res means beginning a story right in the middle of the action. I use this all the time because it's an effective way to hook the reader right away. If something is already happening, why wouldn't they keep reading to see how it resolves itself?Third-party storyteller: This isn't a literary technique per se, because I just came up with that name, but it's a technique that works. Introduce a story through someone who's not connected to the story, such as a local newspaper or television station. Hearing the introduction through a dispassionate and uninterested source adds an element of mystery to the beginning of the book, because the reader doesn't know right away who the story is about -- though they do get a taste of what it's about. Hook your readers with one of these devices, or one of your own design. Get them interested immediately, because if you don't you won't be able to keep them. Polish up your hook, and catch lots of interested readers with it.

Baiting the Hook

How a story begins is really the most important thing about it, because there are readers out there who will look at this and nothing else. If you don't catch those readers who nibble on those first few lines, and get them reeled in, you'll lose them for ever. There are many different literary devices which can be used to hook readers. Get to know them, learn how to use them and then figure out how to make them your own.

Flashback: Go into the distant past to hook readers with a flashback scene. Show what life was like before the stuff that happens in the story, and make it look really amazing. This works well when the book will be showing events that are totally different.Flashforward: Look back at the events of the book with some perspective, dropping tantalizing hints about how the things that happened affected the world, the characters or whatever. This is a common narrative plot device, but a good writer can still make this an exciting technique. Story-within-a-story: It's always interesting to begin a book as a story that's being told to someone else. An example of this occurs in Arabian Nights, in which the storyteller is using short stories to stave off execution. In media res: This sounds like a very fancy technique, but it's really one of the most commonly used. In media res means beginning a story right in the middle of the action. I use this all the time because it's an effective way to hook the reader right away. If something is already happening, why wouldn't they keep reading to see how it resolves itself?Third-party storyteller: This isn't a literary technique per se, because I just came up with that name, but it's a technique that works. Introduce a story through someone who's not connected to the story, such as a local newspaper or television station. Hearing the introduction through a dispassionate and uninterested source adds an element of mystery to the beginning of the book, because the reader doesn't know right away who the story is about -- though they do get a taste of what it's about. Hook your readers with one of these devices, or one of your own design. Get them interested immediately, because if you don't you won't be able to keep them. Polish up your hook, and catch lots of interested readers with it.

Published on July 14, 2014 05:30

July 10, 2014

Getting Mature in YA

Today's topic is mature themes in YA fiction. Just when do books cross the line from young adult into too-adult fare for teens? And when they do, does it really matter?

Get the answers today, plus lots more, in the guest post I did for Paulette's Papers. In the post, I'm talking about my newest book, plus a classic example of YA lit.

Get the answers today, plus lots more, in the guest post I did for Paulette's Papers. In the post, I'm talking about my newest book, plus a classic example of YA lit.

Published on July 10, 2014 05:30

July 9, 2014

Writing 101: Who Are You to Dole Out Poetic Justic?

If you're going to torture a character, I want to enjoy it. I'm not a sadist, I'm referring to poetic justice. It's a pretty common literary technique, but it's also very tricky. Few authors get it right. The thing about poetic justice is this: a little goes a long way.

The House That Martin Built

You'll see poetic justice a lot in storytelling. It's always satisfying when the villainous character meets his just desserts. We always root for the Road Runner to get away, and snicker when the coyote has the anvil dropped on his head. But if you drop too many literary anvils in your books, you're not longer a storyteller. You're a person who likes to dole out suffering. And of course, I've got an example.

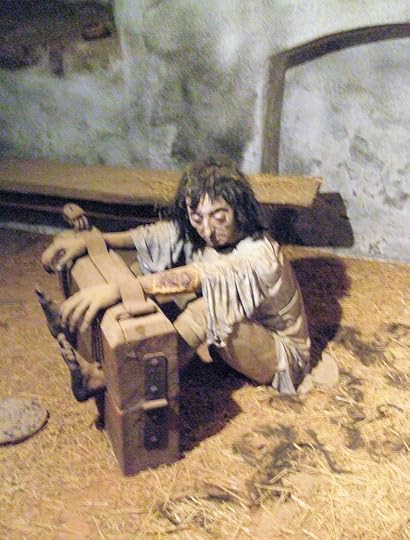

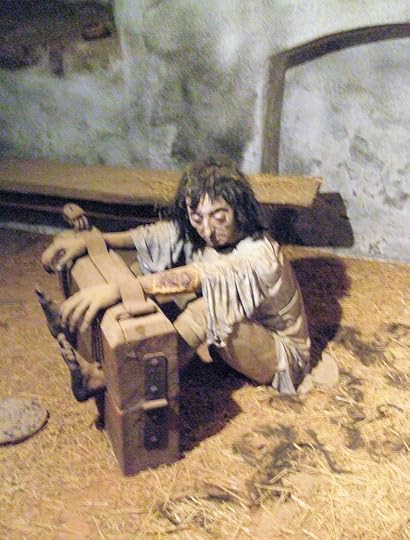

His name is Theon Greyjoy, and this is your only spoiler alert. If you're not caught up to at least Season 4/Book 3 of the Game of Thrones series, skip ahead to the next section. But if you are, then you've seen poetic justice in gruesome, exhausting detail.

Theon Greyjoy betrayed Robb Stark, who was like a brother to him, early in the series. As if that wasn't bad enough, Theon then betrayed all of Winterfell. So there is some delight when Theon himself is captured by a man of the north.

That delight soon turns to nausea, however, when Theon is then tortured in unspeakable ways. His is mentally and physically tortured quite brutally, and it doesn't even end there. Greyjoy is trained and re-conditioned -- brainwashed, if you will -- to become a truly pitiable creature.

And frankly, it's just too much. I'll be honest. I wanted Theon's head chopped off. This was fitting punishment for a man who has betrayed the north. But Theon was flayed, and had his mind and his body destroyed in ways I can't even detail here. That's not poetic justice. That's literary torture from the author.

It is also torturous for me, the person who is supposed to be entertained by all this storytelling. That's what makes poetic justice so very tricky, so difficult to master. You see, everyone has their own limit. Everyone draws their own line in the sand of what they think is okay. And once you've crossed it, you've crossed it.

Punishing Characters

It is much harder to successfully punish a character, without creating a gag reflex in the audience, than it is to redeem a character. A single heroic act can go a very long way toward erasing past misdeeds. But tormenting a character and making the reader watch that person suffer? Now you're playing with fire.

But if you're going to do it anyway, and I know you will, at least do it in a way that's going to work.

Despicable me: First and foremost, make me hate this character. I need to hate them. They ought to do awful things, say awful things, commit horrendous acts and above all else, they need to get in the protagonist's way. Why else do I hate this guy, unless he's an obstacle toward the happiness that I want the main character to have? Doled judiciously: When you go to punish the character, choose your weapon wisely. Maybe it's better to beat this character with a willow switch, rather than flog him with a ball flail. I mean that figuratively. What I'm saying is, maybe don't torture the character before killing them. Maybe don't kill them in a slow, agonizing drowning but in a quick car crash. Maybe instead of taking that next step, settle on taking that first step well and end it before it all gets ugly.Beyond repair: If you are going to make a character suffer, and I mean really suffer, make sure it's a character who is beyond all redemption. Make them commit a truly unforgivable act. It will be much easier for readers to tolerate torture then.

I've found that when it comes to poetic justice, the first taste is sweet. But the more of it you get, the more that taste turns bitter. Doling out poetic justice can be satisfying for the reader...but remember to pull back before it becomes torturous instead.

The House That Martin Built

You'll see poetic justice a lot in storytelling. It's always satisfying when the villainous character meets his just desserts. We always root for the Road Runner to get away, and snicker when the coyote has the anvil dropped on his head. But if you drop too many literary anvils in your books, you're not longer a storyteller. You're a person who likes to dole out suffering. And of course, I've got an example.

His name is Theon Greyjoy, and this is your only spoiler alert. If you're not caught up to at least Season 4/Book 3 of the Game of Thrones series, skip ahead to the next section. But if you are, then you've seen poetic justice in gruesome, exhausting detail.

Theon Greyjoy betrayed Robb Stark, who was like a brother to him, early in the series. As if that wasn't bad enough, Theon then betrayed all of Winterfell. So there is some delight when Theon himself is captured by a man of the north.

That delight soon turns to nausea, however, when Theon is then tortured in unspeakable ways. His is mentally and physically tortured quite brutally, and it doesn't even end there. Greyjoy is trained and re-conditioned -- brainwashed, if you will -- to become a truly pitiable creature.

And frankly, it's just too much. I'll be honest. I wanted Theon's head chopped off. This was fitting punishment for a man who has betrayed the north. But Theon was flayed, and had his mind and his body destroyed in ways I can't even detail here. That's not poetic justice. That's literary torture from the author.

It is also torturous for me, the person who is supposed to be entertained by all this storytelling. That's what makes poetic justice so very tricky, so difficult to master. You see, everyone has their own limit. Everyone draws their own line in the sand of what they think is okay. And once you've crossed it, you've crossed it.

Punishing Characters

It is much harder to successfully punish a character, without creating a gag reflex in the audience, than it is to redeem a character. A single heroic act can go a very long way toward erasing past misdeeds. But tormenting a character and making the reader watch that person suffer? Now you're playing with fire.

But if you're going to do it anyway, and I know you will, at least do it in a way that's going to work.

Despicable me: First and foremost, make me hate this character. I need to hate them. They ought to do awful things, say awful things, commit horrendous acts and above all else, they need to get in the protagonist's way. Why else do I hate this guy, unless he's an obstacle toward the happiness that I want the main character to have? Doled judiciously: When you go to punish the character, choose your weapon wisely. Maybe it's better to beat this character with a willow switch, rather than flog him with a ball flail. I mean that figuratively. What I'm saying is, maybe don't torture the character before killing them. Maybe don't kill them in a slow, agonizing drowning but in a quick car crash. Maybe instead of taking that next step, settle on taking that first step well and end it before it all gets ugly.Beyond repair: If you are going to make a character suffer, and I mean really suffer, make sure it's a character who is beyond all redemption. Make them commit a truly unforgivable act. It will be much easier for readers to tolerate torture then.

I've found that when it comes to poetic justice, the first taste is sweet. But the more of it you get, the more that taste turns bitter. Doling out poetic justice can be satisfying for the reader...but remember to pull back before it becomes torturous instead.

Published on July 09, 2014 05:30