Arsen Darnay's Blog, page 39

November 30, 2013

Marking Nov 13

This year, the only one numberedThirteen, I raked last leaves one coldAnd windy day, and shoveled snow The next with no delay excepting But a single night between—a Night already lit by ChristmasLights put out by those who practiceEarly rites.

This morning on the thin snow leftI saw a few late leaves I shall Remember as marking this uniqueNovember—and silently left Prints of a cat’s paws. Thirteen nowVanes. That number for us has aCertain weight. But when it’s overAll—it’s fate.

This morning on the thin snow leftI saw a few late leaves I shall Remember as marking this uniqueNovember—and silently left Prints of a cat’s paws. Thirteen nowVanes. That number for us has aCertain weight. But when it’s overAll—it’s fate.

Published on November 30, 2013 07:09

November 28, 2013

Gaudium

The word surfaced for us yesterday when reading fairly extensive parts of Pope Francis’ Apostolic Exhortation titled Envangelii Gaudiam available in English

here

. The entire document is some 224 pages long. And there, in the very title of it, is that word: Gaudium, Joy, The Joy of the Gospel.

Those of us born in Europe, and at a time before the absolute spread of secularism took full hold, many will have absorbed an old, old college song which begins with the following verse and is known popularly as “Gaudeamus” and formally as “The Shortness of Life.” We still know the melody too.

Gaudeamus igitur. Let us then all rejoice Iuvenes dum sumus. While yet we are still young Post iucundam iuventutem. For after a youth pleasing, Post molestam senectutem. And after troubled aging, Nos habebit humus. The humus will consume us.

Different forms of joy. Gaudeamus dates to the eighteenth century, per Wikipedia, and therefore celebrates joys associated with the life of the senses. Pope Francis’ Exhortation, reaching us early in the twenty-first, points upward to a dimension which has been practically forgotten with the march of progress—but offers hope for the future.

Those of us born in Europe, and at a time before the absolute spread of secularism took full hold, many will have absorbed an old, old college song which begins with the following verse and is known popularly as “Gaudeamus” and formally as “The Shortness of Life.” We still know the melody too.

Gaudeamus igitur. Let us then all rejoice Iuvenes dum sumus. While yet we are still young Post iucundam iuventutem. For after a youth pleasing, Post molestam senectutem. And after troubled aging, Nos habebit humus. The humus will consume us.

Different forms of joy. Gaudeamus dates to the eighteenth century, per Wikipedia, and therefore celebrates joys associated with the life of the senses. Pope Francis’ Exhortation, reaching us early in the twenty-first, points upward to a dimension which has been practically forgotten with the march of progress—but offers hope for the future.

Published on November 28, 2013 06:29

November 26, 2013

The X Percent Solution

The most famous of these is the 7 percent solution of cocaine Sherlock Holmes used on occasion to stimulate what I must assume had to be his Huge Gray Cells. I last encountered this one quite recently when reading Anthony Horowitz’s The Silk House, a Sherlock Holes story. Horowitz is probably best known for writing British TV series, among them most notably Foyle’s War. Well, there it was again.

The linkage between that seven percent and the drug scene has produced, among others, such phenomena as a book by that title, also a Sherlock Holmes novel, and a rockband, active 1992 through 2003, founded in Austin, Texas. Chancing across that band reminded me again of my abysmal ignorance of pop music. Austin’s Seven Percent Solution belongs to subgenres of rock called shoegaze and spacerock. (My Online Etymology Dictionary is stymied.) Well, to some it’s magic, but descriptions suggest heavy uses of guitars for shoegaze with voices, sort of, absorbed by the din—as, presumably, the mind is by cocaine; and spacerock is similar, but a vast noise by other new electronic instruments is added to the ecstasy.

OED is more helpful in explaining “solution.” It has two meanings, the second derived from the first. The first is the result of dissolution—thus of grains of sugar in a liquid. In that sense something hard is taken apart. The second meaning uses the process of unraveling to indicate loosening, untying, say a knot—or a problem. In that case the solution to a problem also means its disappearance.

Other than pop culture, the chief fans of various numbered solutions are economists. In the recent meltdown problems in Europe (Greece, etc.) some have promoted the 2 percent solution. Stimulate the economies of Europe by expending up to a maximum of 2 percent of the Eurozone’s GDP. Earlier, in the Bush II era, the 4 percent solution aimed at so arranging the world’s economy that all countries grew at 4 percent per annum. The 50 percent solution, also labeled “Get Rich Slowly,” suggests that we all halve our consumption and save the rest. And a recent book, titled the 86% Solution(2005), suggests a fabulous future if only corporations stopped trying to grow by serving the top 14 percent of customers with real money and tried instead to serve the 86 percent that’s left behind.

Is there a 100 percent solution anywhere? It’s often suggested, in various context, in adventure shows. Things have been getting worse and worse for our hero. The hero’s sidekick eventually asks, his or her face a study in terror: “What do we do now?” And the hero then says: “Pray.” Depending on the context, we are supposed to feel even more tense—or to laugh. We last saw this on an episode of People of Interest—that show something of a tour de force. But I got to thinking. That is, after all, the 100 percent solution. It is guaranteed to work—if only you give it time.

The linkage between that seven percent and the drug scene has produced, among others, such phenomena as a book by that title, also a Sherlock Holmes novel, and a rockband, active 1992 through 2003, founded in Austin, Texas. Chancing across that band reminded me again of my abysmal ignorance of pop music. Austin’s Seven Percent Solution belongs to subgenres of rock called shoegaze and spacerock. (My Online Etymology Dictionary is stymied.) Well, to some it’s magic, but descriptions suggest heavy uses of guitars for shoegaze with voices, sort of, absorbed by the din—as, presumably, the mind is by cocaine; and spacerock is similar, but a vast noise by other new electronic instruments is added to the ecstasy.

OED is more helpful in explaining “solution.” It has two meanings, the second derived from the first. The first is the result of dissolution—thus of grains of sugar in a liquid. In that sense something hard is taken apart. The second meaning uses the process of unraveling to indicate loosening, untying, say a knot—or a problem. In that case the solution to a problem also means its disappearance.

Other than pop culture, the chief fans of various numbered solutions are economists. In the recent meltdown problems in Europe (Greece, etc.) some have promoted the 2 percent solution. Stimulate the economies of Europe by expending up to a maximum of 2 percent of the Eurozone’s GDP. Earlier, in the Bush II era, the 4 percent solution aimed at so arranging the world’s economy that all countries grew at 4 percent per annum. The 50 percent solution, also labeled “Get Rich Slowly,” suggests that we all halve our consumption and save the rest. And a recent book, titled the 86% Solution(2005), suggests a fabulous future if only corporations stopped trying to grow by serving the top 14 percent of customers with real money and tried instead to serve the 86 percent that’s left behind.

Is there a 100 percent solution anywhere? It’s often suggested, in various context, in adventure shows. Things have been getting worse and worse for our hero. The hero’s sidekick eventually asks, his or her face a study in terror: “What do we do now?” And the hero then says: “Pray.” Depending on the context, we are supposed to feel even more tense—or to laugh. We last saw this on an episode of People of Interest—that show something of a tour de force. But I got to thinking. That is, after all, the 100 percent solution. It is guaranteed to work—if only you give it time.

Published on November 26, 2013 07:36

November 24, 2013

Monarch Decline

A feature in the New York Times this morning brings news of the belated arrival of the migrating Monarch butterfly in Mexico. The Monarchs always arrive on November 1, a day celebrated in Mexico as the Day of the Dead. This year they were a week late. Both that Day of the Dead (

link

) and the dramatic decline in Monarch population (

link

) have been noted on this blog before. The Times story says that last year 60 million monarchs arrived in Mexico—a greatly diminished display of what the Mexicans think of as the souls of the dead. This year just a shade fewer than 3 million reached Mexico. The cause for this decline is summarized in my second link: it is the use of herbicides which devastates the milkweed.

As behooves people with our convictions, we have a very long view of the future and therefore expect that “this too shall pass.” There are balances in Nature that Long Time corrects even when the Near Term visits its mindless destruction on the environment. But I won’t be around when our version of the milkweed suddenly disappears and human numbers begin to collapse dramatically. At the end, I hope, the few millions left of us will still see a few million Monarchs once more migrating across the continents for landfall on the Day of the Dead.

As behooves people with our convictions, we have a very long view of the future and therefore expect that “this too shall pass.” There are balances in Nature that Long Time corrects even when the Near Term visits its mindless destruction on the environment. But I won’t be around when our version of the milkweed suddenly disappears and human numbers begin to collapse dramatically. At the end, I hope, the few millions left of us will still see a few million Monarchs once more migrating across the continents for landfall on the Day of the Dead.

Published on November 24, 2013 06:31

November 23, 2013

Doctor Who Turns Fifty

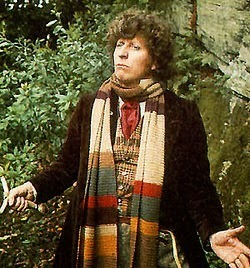

Google Search, in its thematic today, informs me that Doctor Who, the BBC science fiction series, turns fifty on this day. To say that Brigitte and I are great fans of Doctor Who would not be altogether accurate. To say that we are great fans of the fourth Doctor Who, played by Tom Baker, is certainly true. We watched that series with unmixed pleasure in the 1970s with our children. And for a while we also followed, but with decreasing attention, the continuing exploits of the fifth, Peter Davison. That transition also marked our own move from Minneapolis to Detroit. Thereafter? Well, it seemed to us that the Doctor Whos who’d followed had in a way left us behind.

Google Search, in its thematic today, informs me that Doctor Who, the BBC science fiction series, turns fifty on this day. To say that Brigitte and I are great fans of Doctor Who would not be altogether accurate. To say that we are great fans of the fourth Doctor Who, played by Tom Baker, is certainly true. We watched that series with unmixed pleasure in the 1970s with our children. And for a while we also followed, but with decreasing attention, the continuing exploits of the fifth, Peter Davison. That transition also marked our own move from Minneapolis to Detroit. Thereafter? Well, it seemed to us that the Doctor Whos who’d followed had in a way left us behind. Such series are a popular art form not as yet deeply studied (or so it seems to me), but some early terminology has emerged which literary criticism will in the future use to shape its scholarly development. One such phrase is “it jumped the shark,” signifying that what at first was a very fine effort eventually decayed. Brigitte and I are active amateur scholars of this sort of criticism in that retirement gives us the time and the easy availability of series on DVD gives us the means for concentrated study. Our view of many other series is similar: we much approve of parts of them, but the time always comes when multiple disks are returned to the library unwatched because the series has suddenly lost its—should we call it charisma?

The image of Tom Baker is from Wikipedia (link).

Published on November 23, 2013 08:40

In the Land of Individualism

There are some 19 posts on “collectives” on Ghulf Genes, accessible under that word in the Labels section in the left column. Our ability to think in general categories and the shortcuts that generics provide in communication have a very serious drawback, especially when applied to humans. We project collectives of people and then pretend that they are and behave as if they were individuals. Now a word signifying a collective, say United States, or say Dallas—when what we mean is the people that these words can legitimately reference—certainly has an actual reality behind it. The population of the U.S. or of Dallas is at least theoretically present for verification. In actual practice, to be sure, a scientific verification is not possible. To take a census of such collectives takes time; it cannot be done in an instant. Therefore some people will be dead by the time the count is finished; others were not yet present when it began. Cohabitation on a landmass does not meant that every individual on that landmass has exactly the same views. Therefore speaking of these people as if they had some fundamental commonality at the specifically humanlevel is obviously wrong. Yet our ability to generalize—and our love for simplification—make us write headlines like the one that appeared in the New York Times this morning: On Day It Can Never Escape, Dallas Tries To Heal. What the headline actually meant is that 5,000 people met in Dallas (of a total of more than 1.2 million) to commemorate the assassination of President Kennedy.

Complaining of sloppy use of language, and therefore distorted projections of reality, makes me think of Bernard Shaw who naively (or perhaps tongue-in-cheek) hoped to reform the spelling of the English language. Not likely. The assignment of collective guilt on the one hand (Dallas still healing from one assassin’s deed) and collective glory on the other (Boston sharing the Red Sox’ baseball prowess) will continue as ever before. Yes, here, in the land of individualism.

Complaining of sloppy use of language, and therefore distorted projections of reality, makes me think of Bernard Shaw who naively (or perhaps tongue-in-cheek) hoped to reform the spelling of the English language. Not likely. The assignment of collective guilt on the one hand (Dallas still healing from one assassin’s deed) and collective glory on the other (Boston sharing the Red Sox’ baseball prowess) will continue as ever before. Yes, here, in the land of individualism.

Published on November 23, 2013 08:12

November 22, 2013

Projecting Heroes

A day like today, the 50th anniversary of JFK’s assassination, makes me ponder the curious way in which collective emotions are produced and maintained. Kennedy’s legislative efforts had quite stalled just before he died. The media were full of reports wondering if all that charisma would ever produce anything tangible. His charisma had not managed to reach me. My father thought the Kennedys were a true aristocracy—which I found ridiculous. My reaction to the assassination produced no emotion because, well, I was not identified. I also knew very little about Kennedy or his family; later, as more and more came to light, I was more and more persuaded that my distance from this leader had been altogether justified.

The fact is that this man, who, apart from getting elected with much help from his father, had no high level accomplishments, beyond his courageous military service in World War. He had become prominent but did not have a record suggesting future deification. Yet here is his memory, regularly painted on the skies, especially on big anniversaries, in some ways reflecting, as well as being caused by, a rather primitive urge of a segment of the population and of the media elite.

What enabled his projection as a hero, beyond his assassination, was, indeed charisma: a great talent of self-projection. There is his book, Profiles in Courage (co-written with Ted Sorensen but that debt not acknowledged). There was Camelot, etc. This quality, a charismatic personality, Kennedy shared with Ronald Reagan, another hero-projection by another segment of the population but with less media cooperation.

All right. The anniversary today will saturate the media coverage. Ritual marches and music will fill in for lack of great deeds. But how long will this go on? Not too much longer, I would say. Those who were young adults then are all more or less my age. When we pass, this will begin to fade. I infer as much from the fact that I cannot recall any huge April 15 “media day” in any recent year recalling Lincoln’s assassination in 1865. In looking for a President with some genuinely heroic traits, I think of Jimmy Carter. But then there are useful projections suitable to an age severed from basic transcendental values and people who in partial ways attempt to live up to them. The latter are not suitable for painting on the clouds.

The fact is that this man, who, apart from getting elected with much help from his father, had no high level accomplishments, beyond his courageous military service in World War. He had become prominent but did not have a record suggesting future deification. Yet here is his memory, regularly painted on the skies, especially on big anniversaries, in some ways reflecting, as well as being caused by, a rather primitive urge of a segment of the population and of the media elite.

What enabled his projection as a hero, beyond his assassination, was, indeed charisma: a great talent of self-projection. There is his book, Profiles in Courage (co-written with Ted Sorensen but that debt not acknowledged). There was Camelot, etc. This quality, a charismatic personality, Kennedy shared with Ronald Reagan, another hero-projection by another segment of the population but with less media cooperation.

All right. The anniversary today will saturate the media coverage. Ritual marches and music will fill in for lack of great deeds. But how long will this go on? Not too much longer, I would say. Those who were young adults then are all more or less my age. When we pass, this will begin to fade. I infer as much from the fact that I cannot recall any huge April 15 “media day” in any recent year recalling Lincoln’s assassination in 1865. In looking for a President with some genuinely heroic traits, I think of Jimmy Carter. But then there are useful projections suitable to an age severed from basic transcendental values and people who in partial ways attempt to live up to them. The latter are not suitable for painting on the clouds.

Published on November 22, 2013 06:41

November 21, 2013

We Never See All of Venus

We were returning from an outing the other night (on the 19th) and Venus in the sky had a great brilliance. In the wonder of watching it—on the road and then later from home—my early telescopic days back in Kansas returned to me. A bit of knowledge returned as well, but knowledge, unless well-maintained, has a way of eroding. What I remembered was that Venus has phases. And so I said, “It must be a full Venus up there.” Alas.

It turns out that Venus is at its brightest when it is quite close to the earth and shows an intermediate crescent shape. At that point the planet is about 42 million miles from the earth, and now is such a time. The image shown, from the U.S. Naval Observatory’s web site ( link ), is an apparent image, not a photograph. It is for November 19th. Visible portion of Venus will continue to grow, and grow brighter, until December 10th of this year.

When Venus is closest to us (25 million miles away), it goes dark; it is directly between us and the sun. It is full only when it is on the other side of the sun from us—and therefore we cannot ever see her full face. At that point Venus is 162 million miles from us—and bright although Venus is, almost full as it approaches the sun from the back, its brightness has decreased by more than one fifth.

When Venus is closest to us (25 million miles away), it goes dark; it is directly between us and the sun. It is full only when it is on the other side of the sun from us—and therefore we cannot ever see her full face. At that point Venus is 162 million miles from us—and bright although Venus is, almost full as it approaches the sun from the back, its brightness has decreased by more than one fifth.

The next image, from Wikipedia ( link ), shows images of the planet in 2004 (the date stamps are month-day-year). After “new” Venus is reached (the last image), the same images appear but in reversed orientation.

Beautiful planet—but you have to be outside to experience it. Watching Venus and reading about the planet is a nice illustration of the difference between knowledge and experience.

It turns out that Venus is at its brightest when it is quite close to the earth and shows an intermediate crescent shape. At that point the planet is about 42 million miles from the earth, and now is such a time. The image shown, from the U.S. Naval Observatory’s web site ( link ), is an apparent image, not a photograph. It is for November 19th. Visible portion of Venus will continue to grow, and grow brighter, until December 10th of this year.

When Venus is closest to us (25 million miles away), it goes dark; it is directly between us and the sun. It is full only when it is on the other side of the sun from us—and therefore we cannot ever see her full face. At that point Venus is 162 million miles from us—and bright although Venus is, almost full as it approaches the sun from the back, its brightness has decreased by more than one fifth.

When Venus is closest to us (25 million miles away), it goes dark; it is directly between us and the sun. It is full only when it is on the other side of the sun from us—and therefore we cannot ever see her full face. At that point Venus is 162 million miles from us—and bright although Venus is, almost full as it approaches the sun from the back, its brightness has decreased by more than one fifth.The next image, from Wikipedia ( link ), shows images of the planet in 2004 (the date stamps are month-day-year). After “new” Venus is reached (the last image), the same images appear but in reversed orientation.

Beautiful planet—but you have to be outside to experience it. Watching Venus and reading about the planet is a nice illustration of the difference between knowledge and experience.

Published on November 21, 2013 08:43

November 17, 2013

Doris Lessing (1919-2013)

Noting here the passing of Doris Lessing at a delay; this is written some time after the date of her passing on November 17. She touched quite a few members of our family over the years. My own encounter with Lessing took place quite late—when Daughter Michelle gave me Shikasta as a present. Eventually I read the entire series, titled Canopus in Argo: Archives. I’ve not read any of her other seventeen novels. I view the Canopus series are really meaningful fiction, call it science fiction. A major idea, present in that whole series is, SOWF. As for what that means, let me reproduce here the last two paragraphs of a post on another of my blogs (

link

):

In her science fiction novel, Shikasta, Doris Lessing tells the story of a galactic empire, but of a different kind. Multiple planetary settlements have taken place over many eons from the star system Canopus, in the constellation of Argos. All kinds of species have been, as it were, planted, and they are evolving. Sustaining their evolution is an energetic emanation called Substance-Of-We-Feeling, abbreviated SOWF. It isn’t necessary for simple survival, but it is what sustains harmonious development. All is well for a long, long time—but then the emissaries from Canopus notice that something very troubling has taken place. An unexpected cosmic realignment causes the flow of SOWF to thin. Another empire, Canopus’ enemy, Puttoria, attempts to exploit this situation. A degenerative disease begins to affect settlements, among them Shikasta (read Earth); it’s not a physical disease; it is the higher levels—spiritual life, community life—that are affected.

The story of Shikasta, of course, merits interpretation as a new or as a renewed revelation—this one emanating from Sufi roots. Doris Lessing was associated with the Sufi teaching projected by Idries Shah from Britain. When I first read Shikasta, I had to smile when I encountered SOWF; to me it was an obvious reference to Sufism; later I discovered that others had had much the same thought. Lessing’s series of novels, collectively known as Canopus in Argos, is the framing of a cosmology in modern terms, thus accessible to a secular and technological age. SOWF functions as Grace—a gift, a source of higher nutrition, regenerative, as Webster’s has it. Lessing’s intent, to be sure, is far from suggesting that God is a distant galactic civilization. The effect of her, alas, very difficult fiction is to make such ideas of a conscious and meaningful cosmic plan—in which, as it were, energetic emanations like Grace play a vital role—visible to modern minds and, when thought about, illuminative of ancient and by now moribund structures of belief we’ve come to dismiss as backward superstitions.

Farewell Doris Lessing. Your journey continues.

In her science fiction novel, Shikasta, Doris Lessing tells the story of a galactic empire, but of a different kind. Multiple planetary settlements have taken place over many eons from the star system Canopus, in the constellation of Argos. All kinds of species have been, as it were, planted, and they are evolving. Sustaining their evolution is an energetic emanation called Substance-Of-We-Feeling, abbreviated SOWF. It isn’t necessary for simple survival, but it is what sustains harmonious development. All is well for a long, long time—but then the emissaries from Canopus notice that something very troubling has taken place. An unexpected cosmic realignment causes the flow of SOWF to thin. Another empire, Canopus’ enemy, Puttoria, attempts to exploit this situation. A degenerative disease begins to affect settlements, among them Shikasta (read Earth); it’s not a physical disease; it is the higher levels—spiritual life, community life—that are affected.

The story of Shikasta, of course, merits interpretation as a new or as a renewed revelation—this one emanating from Sufi roots. Doris Lessing was associated with the Sufi teaching projected by Idries Shah from Britain. When I first read Shikasta, I had to smile when I encountered SOWF; to me it was an obvious reference to Sufism; later I discovered that others had had much the same thought. Lessing’s series of novels, collectively known as Canopus in Argos, is the framing of a cosmology in modern terms, thus accessible to a secular and technological age. SOWF functions as Grace—a gift, a source of higher nutrition, regenerative, as Webster’s has it. Lessing’s intent, to be sure, is far from suggesting that God is a distant galactic civilization. The effect of her, alas, very difficult fiction is to make such ideas of a conscious and meaningful cosmic plan—in which, as it were, energetic emanations like Grace play a vital role—visible to modern minds and, when thought about, illuminative of ancient and by now moribund structures of belief we’ve come to dismiss as backward superstitions.

Farewell Doris Lessing. Your journey continues.

Published on November 17, 2013 11:30

Cerberus’ Bark

Having recently wondered in public about the sister of Pegasus, one of Brigitte’s comments yesterday, referencing the ancient three-headed hell-hound, Cerberus, made me wonder how a creature like that might have barked. Would the Guardian of the Underworld greet its visitors with a simultaneous “Woof,” “Woof,” “Woof” issuing from three hellish jaws? Or would any of the heads just give it a pass (as shown in the illustration I’m including)? Got to thinking, further, that the hell dog would probably have language, and, after acquiring recognition from the Romans, might have barked in Latin thus: “Servus,” “Servus,” “Servus.”

Published on November 17, 2013 10:19

Arsen Darnay's Blog

- Arsen Darnay's profile

- 6 followers

Arsen Darnay isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.