Arsen Darnay's Blog, page 10

January 20, 2016

Channeling Solomon

For the first time in history, it may be necessary for the Supreme Court of the United States to hire a qualified Medium. Why is that? Well, the answer is advancing technology. It is now possible for a couple to conceive a child by in vitro fertilization of a mother’s ovum and a father’s sperm. Better yet, the resulting embryo may then be frozen to be gestated (or not) based on the couple’s chosen schedule. But what if, in the meanwhile, the couple gets divorced? And one of them is unwilling actually to have the child (once it has been thawed out). You can’t divide an embryo in half. Or can you? And what if they are twins. Such cases are multiplying. Soon SCOTUS (as the knowledgeable refer to the Court) may get a case to decide. The difficulties are great—even if a precedent exists. But for best practice, perhaps channeling Solomon himself may be appropriate. Therefore a qualified Medium!

Published on January 20, 2016 05:42

January 18, 2016

MLK Morning 2016

Gorgeous sunny morningThe merest breath of snow.The fog seems to have frozen,Has simply left the air,And rests on grass and thatchWhile the sun, arrestedIn its path, stopped at this Vision itself had wrought,Cannot move on withoutA moment’s meditation.

Published on January 18, 2016 06:30

January 17, 2016

A Curious Controversy

On a quite casual look to see how heroin is derived, ultimately, from poppies, I came across the following text in Wikipedia’s article on “Morphine” (

link

):

Later it was found that morphine was more addictive than either alcohol or opium, and its extensive use during the American Civil War allegedly resulted in over 400,000 sufferers from the “soldier’s disease” of morphine addiction. This idea has been a subject of controversy, as there have been suggestions that such a disease was in fact a fabrication; the first documented use of the phrase “soldier’s disease” was in 1915.

I spent the best part of half-a-day trying to find the actual source for that number—and indeed for that phrase. Wikipedia’s references were in part non-functional. In due course I discovered that the number comes from a Book entitled Drug Dependence and Abuse Resource Book, published in 1971 by the National District Attorney’s Association; in that book a single article, by Gerald Starkey, entitled “The Use and Abuse of Opiates and Amphetamines” contains the passage I quote below. (Starkey, by the way, is shown as an MD in the original book—but later, one opponent labeled him a “yellow journalist”—see below.) The passage itself is quoted in Shooting Up: A History of Drugs and War by Lukasz Kamienski ( link ). Here it is:

In 1865 there were an estimated 400,00 young War veterans addicted to Morphine… The returning veteran could be identified because he had a leather thong around his neck and a leather bag [with] Morphine Sulfate tablets, along with a syringe and a needle issued to the soldier on his discharge… This was called the “Soldier’s Disease.”

Wikipedia, above, also refers to a “controversy.” The source of that controversy is one Jerry Mandel, particularly his paper titled “The Mythical Roots of U.S. Drug Policy: Soldier’s Disease and Addiction in the Civil War,” available here . Mandel’s paper appears under the imprint of the Drug Reform Coordinating Network, better known, perhaps, as StoptheDrugWar.org. He argues that major addiction (say on the scale of 400,000) was not an actual fact of history but that, on the contrary, it is a much later phenomenon, evolved to support the War on Drugs. His claim is that the phrase “soldier’s disease” was not used in print until 1915. One writer who uses Mandel’s argument (of several such) also labeled Starkey as a “yellow journalist.”

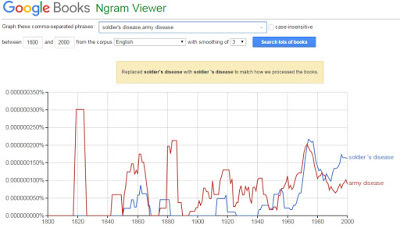

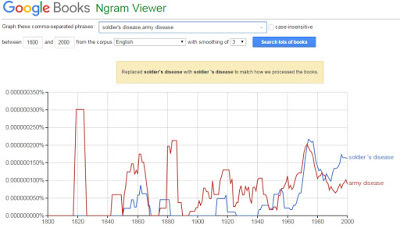

Who do you believe? I tried an experiment. I asked Google Ngrams to trace the usage of two phrases: “soldier’s disease” and “army disease”; the latter term was also supposedly widely used during the Civil War to refer to drug addiction. Here is what Google had to say:

It would seem that the phrase “soldier’s disease” first appears strongly in the Civil War period—and is now back in force—thanks to controversies surrounding the legalization of drugs…

Later it was found that morphine was more addictive than either alcohol or opium, and its extensive use during the American Civil War allegedly resulted in over 400,000 sufferers from the “soldier’s disease” of morphine addiction. This idea has been a subject of controversy, as there have been suggestions that such a disease was in fact a fabrication; the first documented use of the phrase “soldier’s disease” was in 1915.

I spent the best part of half-a-day trying to find the actual source for that number—and indeed for that phrase. Wikipedia’s references were in part non-functional. In due course I discovered that the number comes from a Book entitled Drug Dependence and Abuse Resource Book, published in 1971 by the National District Attorney’s Association; in that book a single article, by Gerald Starkey, entitled “The Use and Abuse of Opiates and Amphetamines” contains the passage I quote below. (Starkey, by the way, is shown as an MD in the original book—but later, one opponent labeled him a “yellow journalist”—see below.) The passage itself is quoted in Shooting Up: A History of Drugs and War by Lukasz Kamienski ( link ). Here it is:

In 1865 there were an estimated 400,00 young War veterans addicted to Morphine… The returning veteran could be identified because he had a leather thong around his neck and a leather bag [with] Morphine Sulfate tablets, along with a syringe and a needle issued to the soldier on his discharge… This was called the “Soldier’s Disease.”

Wikipedia, above, also refers to a “controversy.” The source of that controversy is one Jerry Mandel, particularly his paper titled “The Mythical Roots of U.S. Drug Policy: Soldier’s Disease and Addiction in the Civil War,” available here . Mandel’s paper appears under the imprint of the Drug Reform Coordinating Network, better known, perhaps, as StoptheDrugWar.org. He argues that major addiction (say on the scale of 400,000) was not an actual fact of history but that, on the contrary, it is a much later phenomenon, evolved to support the War on Drugs. His claim is that the phrase “soldier’s disease” was not used in print until 1915. One writer who uses Mandel’s argument (of several such) also labeled Starkey as a “yellow journalist.”

Who do you believe? I tried an experiment. I asked Google Ngrams to trace the usage of two phrases: “soldier’s disease” and “army disease”; the latter term was also supposedly widely used during the Civil War to refer to drug addiction. Here is what Google had to say:

It would seem that the phrase “soldier’s disease” first appears strongly in the Civil War period—and is now back in force—thanks to controversies surrounding the legalization of drugs…

Published on January 17, 2016 13:35

January 13, 2016

Metrics

What happens when we’re at the doctor’s office and it is the State of the Body rather than that of the Union is under examination. Apart from a general look at our posture, color, and facial expression, the doctor will check three metrics—usually already obtained by his assisting nurse: temperature, blood pressure, and body weight. For good measure, the doctor may, in addition, have us sit with legs dangling and use a little hammer to see if our reflexes work. The reflexes work. The temperature is falls into the range of 95.5 to 98.8F. Our blood pressure is 120/80—the top number when the heart is pushing blood, the low for when its very temporarily resting. Our color is normal; we managed a so-so smile. We are neither too light nor too heavy. All’s well, with the State of the Body.

Similar metrics—of which, curiously, average body weight is also one—applies to the State of the Union. Here the big measures are the rate of change in Gross Domestic Product, in the Total Deficit, Employment, Income, Poverty, Income Distribution, Birth Rate, change in the Obesity Rate, especially of children, and Imminent Threat of Violence at our borders.

The earliest State of the Union reports were written and were usually heavy on international relations and sometimes quite numerical regarding budget matters; but it never occurred to early presidents to worry about galloping obesity. (For complete texts, see this link). These days State of the Union reports are heavy on Visions, Feelings, and other handy insubstantialities. It would seem that returning to metrics might be a pretty good change—real measurements of what is going on. These should be presented as graphics—and the Bureau of the Census adequately funded so that, for instance, numbers of the 2015 actual Poverty Rate would be available in January 2016; they are not. But just as such issues such as Poverty, Obesity, and Income Distribution are becoming important indicators, so also should be what is happening beyond our borders—and broad perspectives might be useful.

What we need, in other words, is a metric-rich State of the Union combined with a sober State of the World with foresight built in. It might be well to discuss global plagues, global population trends, global water resources, the state of the oceans, and the great wars—not least directly naming the Mideast conflict as the evolution of a 100-years war within the Muslim culture which will still be raging for another 70 years or so.

Just a thought…

Similar metrics—of which, curiously, average body weight is also one—applies to the State of the Union. Here the big measures are the rate of change in Gross Domestic Product, in the Total Deficit, Employment, Income, Poverty, Income Distribution, Birth Rate, change in the Obesity Rate, especially of children, and Imminent Threat of Violence at our borders.

The earliest State of the Union reports were written and were usually heavy on international relations and sometimes quite numerical regarding budget matters; but it never occurred to early presidents to worry about galloping obesity. (For complete texts, see this link). These days State of the Union reports are heavy on Visions, Feelings, and other handy insubstantialities. It would seem that returning to metrics might be a pretty good change—real measurements of what is going on. These should be presented as graphics—and the Bureau of the Census adequately funded so that, for instance, numbers of the 2015 actual Poverty Rate would be available in January 2016; they are not. But just as such issues such as Poverty, Obesity, and Income Distribution are becoming important indicators, so also should be what is happening beyond our borders—and broad perspectives might be useful.

What we need, in other words, is a metric-rich State of the Union combined with a sober State of the World with foresight built in. It might be well to discuss global plagues, global population trends, global water resources, the state of the oceans, and the great wars—not least directly naming the Mideast conflict as the evolution of a 100-years war within the Muslim culture which will still be raging for another 70 years or so.

Just a thought…

Published on January 13, 2016 09:17

January 12, 2016

Terrae Incognitae

A CNN headline yesterday stated: Farewell Starman: World mourns loss of a musical giant. The person mourned was David Bowie, dead at 69, a transformative figure in Rock Music. I did not recognize the name at all—but it brought an echo. I knew at least one famous Bowie, Jim Bowie, the American nineteenth century adventurer, he who’s famous for the Bowie Knife. And I’ve known about him since I was ten. That was in Europe, but I was a great admirer of American heroes and much wishing I had a knife like Bowie’s. The David I’m talking about was born just about then.

I didn’t recognize the name because, like most people, I have terrae incognitae in my life. The great majority of them, in my case, have to do with the arts, particularly the popular arts, and especially pop music—or the institutional aspects of the movie business.

But when the “world mourns” one is inclined to look a little closer. Well, today I learned that David Bowie, who was born in London on January 8, 1947, was born as David Robert Jones. In his early musical career, he went by the name of Davy Jones, a name that no doubt meant to echo Davy Jones’ Locker, thus where drowned sailors gather after death. Our David, however, had a problem. In the highly competitive world of Rock, another Davy Jones, Davy Jones of the Monkees, was also on the musical stage. To differentiate himself from that competitor, our David changed his name to David Bowie and—here’s the rub—he renamed himself deliberately after the famed Jim Bowie of the knife. The link in my mind that sprang up over that last name was not just a coincidence.

Yesterday also threw a brief light on another of my unknown earths. News also came yesterday of the Golden Globes Awards. Bowie perhaps had prepared me for a minor shock. I realized that I knew nothing about that award either. The Oscars were familiar (the Academy Awards), but Golden Globes? Well, the Oscars have been around since 1929, the Golden Globes “only” since 1947—the year of Bowie’s birth. The Movie Industry is better known to me than Rock, but not well enough to arouse a desire to follow its annual rituals of recognition. And that, rituals of recognition, in part illuminate my own ignoring of large segments of art.

The arts were at the very center of my interest in youth. As I studied them intensely, I became aware of something. There came a time—beginning somewhere in the Renaissance but certainly maturing by the time of the early twentieth century. An invisible Curtain descended. On one side of it, the object celebrated by the art was the total focus of the activity; on the other side of that Curtain, it was the technique used (expressionism, pointislism, etc.) and later the artist who became the focus; innovation and transformation became a badge of achievement; the art itself slowly became a mere means by which the artist became visible to the World. Having made that discovery, I grew quite indifferent to those terrae of the arts in which this transformation was reaching its climax and gradually transforming itself into a means for achieving fame and wealth.

I didn’t recognize the name because, like most people, I have terrae incognitae in my life. The great majority of them, in my case, have to do with the arts, particularly the popular arts, and especially pop music—or the institutional aspects of the movie business.

But when the “world mourns” one is inclined to look a little closer. Well, today I learned that David Bowie, who was born in London on January 8, 1947, was born as David Robert Jones. In his early musical career, he went by the name of Davy Jones, a name that no doubt meant to echo Davy Jones’ Locker, thus where drowned sailors gather after death. Our David, however, had a problem. In the highly competitive world of Rock, another Davy Jones, Davy Jones of the Monkees, was also on the musical stage. To differentiate himself from that competitor, our David changed his name to David Bowie and—here’s the rub—he renamed himself deliberately after the famed Jim Bowie of the knife. The link in my mind that sprang up over that last name was not just a coincidence.

Yesterday also threw a brief light on another of my unknown earths. News also came yesterday of the Golden Globes Awards. Bowie perhaps had prepared me for a minor shock. I realized that I knew nothing about that award either. The Oscars were familiar (the Academy Awards), but Golden Globes? Well, the Oscars have been around since 1929, the Golden Globes “only” since 1947—the year of Bowie’s birth. The Movie Industry is better known to me than Rock, but not well enough to arouse a desire to follow its annual rituals of recognition. And that, rituals of recognition, in part illuminate my own ignoring of large segments of art.

The arts were at the very center of my interest in youth. As I studied them intensely, I became aware of something. There came a time—beginning somewhere in the Renaissance but certainly maturing by the time of the early twentieth century. An invisible Curtain descended. On one side of it, the object celebrated by the art was the total focus of the activity; on the other side of that Curtain, it was the technique used (expressionism, pointislism, etc.) and later the artist who became the focus; innovation and transformation became a badge of achievement; the art itself slowly became a mere means by which the artist became visible to the World. Having made that discovery, I grew quite indifferent to those terrae of the arts in which this transformation was reaching its climax and gradually transforming itself into a means for achieving fame and wealth.

Published on January 12, 2016 09:10

January 10, 2016

Those 25 Basis Points

The U.S. GDP clocked in at $17.968 trillion last year—a right rather huge, indeed almost unthinkable number. But the business news throughout 2015 concerned agonizing reflections on whether or not the Federal Reserve would actually raise the Federal Funds Rate, and if yes, when and by how much. Let’s look at this for a moment.

The Federal Funds Rate (FFR) is the interest charged by the Fed to lend money to banks, usually for a short period of time. The banks borrowing this money then have more to lend. If the FFR rises, money gets more expensive; if it drops, money gets cheaper.

The Fed has a target rate for such lending. Until December 16 of last year, that target was a range from 0 to 25 basis points. What those are will be explained in due time. The range exists because Fed lending can vary in price between those two number. Last December the actual rate charged averaged between 13 and 15 basis points up to December 16. Then the Fed changed its target range to 25 to 50 basis points. In other words, the average of all lending had to fall somewhere at or between those numbers. Since the increase, the actual FFR rate has been around 36 basis points, thus significantly less than the maximum of 50. For a look at December results, see this table provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York ( link ).

So how much is that 25 point increase the Fed finally decided to institute? The best way to explain that is by reference to a percentage point. Everybody understands that a percent is one hundredth part of something. 1% of a dollar is a penny. Now each percent could also be divided by 100. In that case each percent would have 100 parts. And each of those parts would have a name. And that name is the Basis Point. So there are 100 basis points inside each penny.

Now just as a trillion is difficult to grasp (never mind nearly 18 of them) so also a basis point is quite invisible—a minute portion of a penny you might be able to scratch off with a very hard knife. 25 basis points are, therefore, a quarter of a penny.

When we increase the quantity of money, those basis point start having meaning. On $100 it’s a quarter, on $1,000 is $2.50, on 10,000 it’s $25. But, of course, when you borrow millions daily, it actually becomes quite visible. What about 25 basis points of that $18 billion? Well, on that amount those basis points produce a charge of $45 million. But, when I think about it, that won’t even buy me a single nuclear submarine; we’re talking billions of dollars per unit there…

The Federal Funds Rate (FFR) is the interest charged by the Fed to lend money to banks, usually for a short period of time. The banks borrowing this money then have more to lend. If the FFR rises, money gets more expensive; if it drops, money gets cheaper.

The Fed has a target rate for such lending. Until December 16 of last year, that target was a range from 0 to 25 basis points. What those are will be explained in due time. The range exists because Fed lending can vary in price between those two number. Last December the actual rate charged averaged between 13 and 15 basis points up to December 16. Then the Fed changed its target range to 25 to 50 basis points. In other words, the average of all lending had to fall somewhere at or between those numbers. Since the increase, the actual FFR rate has been around 36 basis points, thus significantly less than the maximum of 50. For a look at December results, see this table provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York ( link ).

So how much is that 25 point increase the Fed finally decided to institute? The best way to explain that is by reference to a percentage point. Everybody understands that a percent is one hundredth part of something. 1% of a dollar is a penny. Now each percent could also be divided by 100. In that case each percent would have 100 parts. And each of those parts would have a name. And that name is the Basis Point. So there are 100 basis points inside each penny.

Now just as a trillion is difficult to grasp (never mind nearly 18 of them) so also a basis point is quite invisible—a minute portion of a penny you might be able to scratch off with a very hard knife. 25 basis points are, therefore, a quarter of a penny.

When we increase the quantity of money, those basis point start having meaning. On $100 it’s a quarter, on $1,000 is $2.50, on 10,000 it’s $25. But, of course, when you borrow millions daily, it actually becomes quite visible. What about 25 basis points of that $18 billion? Well, on that amount those basis points produce a charge of $45 million. But, when I think about it, that won’t even buy me a single nuclear submarine; we’re talking billions of dollars per unit there…

Published on January 10, 2016 10:21

January 9, 2016

The Three Kims

Korea came to be divided in 1948, thus before the Korean War began. That division came about because the two victors of World War II, the Soviets and the United States, divided the country into uneven halves: the bigger but mountainous North and the more advanced but smaller South. The victors, to be sure, would rapidly evolve into ideological opponents. But perhaps the more telling part of the situation was that the first of the Kims to which my title refers, Kim Il-Sung (1912-1994—Kim is the last name), became the premier of North Korea in 1948. Something in his genes or makeup—together with the ideological conflict which the division of Korea represented—has produced one of the more curious phenomena in international relations: here is a tiny country, representing 0.35 percent of the world’s population; it exist in a kind of independence by using now one and now some other of the Great Powers of the world to side with it (more or less half-heartedly always), so that it can remain unaligned—while the ruling class, i.e. the Kims and their followers, can live in luxury while the population is poor.

Concerning that poverty, let me contrast South and North Korea. The North has more land (120,540 square km) the South has less (100,210 sq km). The North has fewer people (24.9 million), the South has more (50.6 million). The north has a GDP of $15.4 billion ($621 per capita); the South has $1.39 trillion ($27,513 per capita).

Concerning the Kims, they have been able to retain power over three generations. Kim Il-Sung was followed by his son (Kim Jong-il (1941-2011)) and by his grandson (Kim Jong-un, born 1983)—and the Young One seems as able as his elders in playing the same game of chicken, threatening the Great Powers—and the rich Korea to his south; this has kept the population poor, in great anxiety of war or terror, and the Kims in regal comfort.

Kim the First exploited tensions between China and the Soviets; Kim the Second oversaw the development of nuclear weapons—permitted to do so because firm action to prevent it would have involved high risks of war between the U.S., China, or Russia. Kim the Third, well aware of what the real game is, is now making his own contribution by exploding what may or may not have been an H-bomb.

The Three Kims are a fascinating phenomenon: how to exploit the tension between great powers by playing a game of nuclear arms. Such tensions, evidently, are built into collective human experience and cannot be put to rest no matter how the world changes. The situation now is vastly different than it was in 1948, but the Korean situation is unchanged. Global conflict, to be sure, is also in the genes, albeit in the collective genes. The last thing the Kims will ever do is use their weapons in warfare. Why do I say that? If they ever did, the Game of Kims would abruptly end. In the meanwhile, China might be persuaded to act more energetically by being granted certain title to the islands it is building in the South China Sea. But that could not be done without transforming the uneasy balance in Asia. Meanwhile the Jong-un is still young. He already has a daughter. Will a Kim the Fourth be soon waiting in the wings for yet another round of this game?

Concerning that poverty, let me contrast South and North Korea. The North has more land (120,540 square km) the South has less (100,210 sq km). The North has fewer people (24.9 million), the South has more (50.6 million). The north has a GDP of $15.4 billion ($621 per capita); the South has $1.39 trillion ($27,513 per capita).

Concerning the Kims, they have been able to retain power over three generations. Kim Il-Sung was followed by his son (Kim Jong-il (1941-2011)) and by his grandson (Kim Jong-un, born 1983)—and the Young One seems as able as his elders in playing the same game of chicken, threatening the Great Powers—and the rich Korea to his south; this has kept the population poor, in great anxiety of war or terror, and the Kims in regal comfort.

Kim the First exploited tensions between China and the Soviets; Kim the Second oversaw the development of nuclear weapons—permitted to do so because firm action to prevent it would have involved high risks of war between the U.S., China, or Russia. Kim the Third, well aware of what the real game is, is now making his own contribution by exploding what may or may not have been an H-bomb.

The Three Kims are a fascinating phenomenon: how to exploit the tension between great powers by playing a game of nuclear arms. Such tensions, evidently, are built into collective human experience and cannot be put to rest no matter how the world changes. The situation now is vastly different than it was in 1948, but the Korean situation is unchanged. Global conflict, to be sure, is also in the genes, albeit in the collective genes. The last thing the Kims will ever do is use their weapons in warfare. Why do I say that? If they ever did, the Game of Kims would abruptly end. In the meanwhile, China might be persuaded to act more energetically by being granted certain title to the islands it is building in the South China Sea. But that could not be done without transforming the uneasy balance in Asia. Meanwhile the Jong-un is still young. He already has a daughter. Will a Kim the Fourth be soon waiting in the wings for yet another round of this game?

Published on January 09, 2016 09:51

January 4, 2016

The Miniaturization of Flight

I learned today that around a million “drones” were packaged for this Christmas this year; indeed I saw a kiosk at a nearby mall busily demonstrating and selling them—the devices swirling around in the air. They came in two varieties: those with and those without a camera.

Miniaturization is probably part of all evolving technology, biological or mechanical. The most memorable for me are clocks: huge things that once needed tall towers—and brass bells to broadcast the time to those who couldn’t see the towers—or by night. Now watches are easily worn on the wrist. The radio figures in my memories too. The first one I saw as a child at grandmother’s house had a vast, black horn. Radios were big—pieces of furniture. One such—too nice to discard—still lives in our garage, and has so lived, protected by wrapping, for thirty years. Now radios have become small enough to fit into an ear.

Miniaturization is probably part of all evolving technology, biological or mechanical. The most memorable for me are clocks: huge things that once needed tall towers—and brass bells to broadcast the time to those who couldn’t see the towers—or by night. Now watches are easily worn on the wrist. The radio figures in my memories too. The first one I saw as a child at grandmother’s house had a vast, black horn. Radios were big—pieces of furniture. One such—too nice to discard—still lives in our garage, and has so lived, protected by wrapping, for thirty years. Now radios have become small enough to fit into an ear.

TVs, computers, telephones. The list of objects miniaturized is quite long but, deep down, associated with humanity’s growing skill in making transistors ever smaller. Transistors are the fundamental amplifying and switching devices of electronics—and therefore central in communications and computation. The illustration included (from Wikipedia here ), shows the diminution of the size in these devices. The last of these, a so-called small-outline transistor, has a an internal diameter ranging from 1.9 to 0.5 millimeters.

When you think about it, the miniaturization of flight has taken rather a long time. It has required development of real-time radio guidance so that the “pilot” can constantly pinpoint the object’s location—and the locations of other objects in its immediate vicinity. Those problems have now been solved—although I wonder what millions upon millions of such devices—each using the limited wireless spectrum—will have on other forms of communication.

If wishes were horses, beggars would ride. For about $150 (that’s a little drone with a camera), our eyes can already take a ride although the beggar is still slouched on a sunny veranda.

Miniaturization is probably part of all evolving technology, biological or mechanical. The most memorable for me are clocks: huge things that once needed tall towers—and brass bells to broadcast the time to those who couldn’t see the towers—or by night. Now watches are easily worn on the wrist. The radio figures in my memories too. The first one I saw as a child at grandmother’s house had a vast, black horn. Radios were big—pieces of furniture. One such—too nice to discard—still lives in our garage, and has so lived, protected by wrapping, for thirty years. Now radios have become small enough to fit into an ear.

Miniaturization is probably part of all evolving technology, biological or mechanical. The most memorable for me are clocks: huge things that once needed tall towers—and brass bells to broadcast the time to those who couldn’t see the towers—or by night. Now watches are easily worn on the wrist. The radio figures in my memories too. The first one I saw as a child at grandmother’s house had a vast, black horn. Radios were big—pieces of furniture. One such—too nice to discard—still lives in our garage, and has so lived, protected by wrapping, for thirty years. Now radios have become small enough to fit into an ear.TVs, computers, telephones. The list of objects miniaturized is quite long but, deep down, associated with humanity’s growing skill in making transistors ever smaller. Transistors are the fundamental amplifying and switching devices of electronics—and therefore central in communications and computation. The illustration included (from Wikipedia here ), shows the diminution of the size in these devices. The last of these, a so-called small-outline transistor, has a an internal diameter ranging from 1.9 to 0.5 millimeters.

When you think about it, the miniaturization of flight has taken rather a long time. It has required development of real-time radio guidance so that the “pilot” can constantly pinpoint the object’s location—and the locations of other objects in its immediate vicinity. Those problems have now been solved—although I wonder what millions upon millions of such devices—each using the limited wireless spectrum—will have on other forms of communication.

If wishes were horses, beggars would ride. For about $150 (that’s a little drone with a camera), our eyes can already take a ride although the beggar is still slouched on a sunny veranda.

Published on January 04, 2016 11:01

January 3, 2016

One Tale Told, Retold

In 1977 we were in transition between Virginia and Minnesota. I was already in Minneapolis; the family was still in Fairfax, VA when Star Wars made its debut in March of that year. I went to see it at a drive-in movie on an impulse: an advertising placard caught my eye as I was driving to my temporary apartment. The film made a great impression on me—not its science fiction aspects, which were quite stunning, of course, but rather something that was altogether novel in the environment of that time. The film deliberately presented to our popular culture the transcendental aspect of reality, and did so in a straightforward, serious, and approving manner. It was the Force—which was with you.

I did not know then what has taken place since. The story has been retold seven times since then—with essentially the same plot and by archetypal character: Good versus evil, and the Good triumphant by the slenderest of margins.

In the transition between 2015 and 2016, another show, Downton Abbey, is beginning its last season on this side of the divide. It is another case of one tale, retold each season. Such a feat is possible if one’s drawn to the story by the characters; Downton’s characters have much more human depth than Star Wars’, to be sure, but the repeating plot, with endless variations, is once more a kind of departure from our flagging faith in Progress and return to eternal values. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. We haven’t seen Season VI of Downton Abbey, but we’re fairly sure that its story line will faithfully echo all earlier seasons: same conflicts, same resolutions. One watches such shows not for the predictable plot but just to see how life unfolds, infinitely variably but ever the same.

I did not know then what has taken place since. The story has been retold seven times since then—with essentially the same plot and by archetypal character: Good versus evil, and the Good triumphant by the slenderest of margins.

In the transition between 2015 and 2016, another show, Downton Abbey, is beginning its last season on this side of the divide. It is another case of one tale, retold each season. Such a feat is possible if one’s drawn to the story by the characters; Downton’s characters have much more human depth than Star Wars’, to be sure, but the repeating plot, with endless variations, is once more a kind of departure from our flagging faith in Progress and return to eternal values. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. We haven’t seen Season VI of Downton Abbey, but we’re fairly sure that its story line will faithfully echo all earlier seasons: same conflicts, same resolutions. One watches such shows not for the predictable plot but just to see how life unfolds, infinitely variably but ever the same.

Published on January 03, 2016 08:26

January 1, 2016

Through Nature's Eyes

Green grass shows through half-hearted snow.The sky is uniformly grey.The evergreens are tall and dark.The other trees are stark and bare.A few new flakes began to fall,Slightly angled in descent,A while ago, as I looked outStruck by silence and by the same,The same old face of Nature,Always there, moving or still,Ever-changing yet stubbornlyStill the same, standing, lying down—Like that grass under its frowning snow.Now new snow is falling thicker. A small gust sweeps a curl of itRight off the roof. The houseBack there is still asleep, Its windows dark, the blue tarpCovering a boat still dully blue.It’s January 1st out there,A new beginning—but Nature’s Eyes see just another day.

Published on January 01, 2016 07:18

Arsen Darnay's Blog

- Arsen Darnay's profile

- 6 followers

Arsen Darnay isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.